We've got two reviews for you today. First, Tucker Stone himself writes about M.S. Harkness's Dxpx Dxxlxr.

A collection of minicomics by M.S. Harkness, D*P* D**L*R is aggressive, confident work by a cartoonist whose obvious affection for boldness and speed conceals a methodical structure and pacing. Comics that in other hands would have allowed for an exercise in crude mark-making so as to complement narrative tempo here play out with an eye towards broader legibility--this, more than other comics playing in the here-is-some-gnarly-shit-I'm-into genre, is a comic that won't seem foreign to a broader audience less willing to engage with obfuscation.

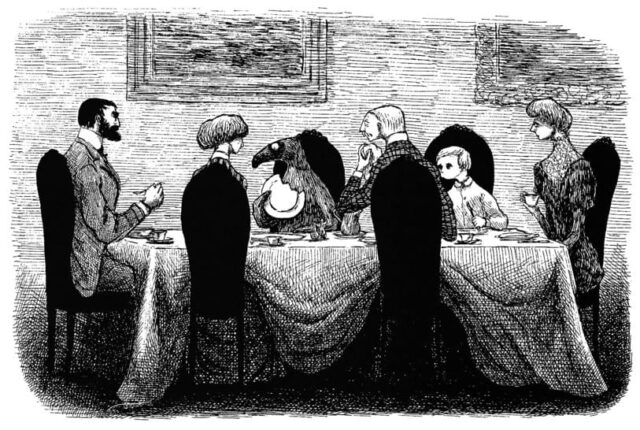

The three stories here all seem to be drawn from Harkness's life, or at least, from how Harkness chooses to present her life to others. (Harkness uses the same stand-in throughout, an angular character who also served as lead in her previous book, Tinderella.) Opening with a fast paced karaoke take on SZA that sees its protagonist tearing through enough life experiences to fill a whole shelf of comics from more sedate storytellers, this first tale features a bukkake sequence, a boot-removing assault as response to street-side cat-calling, a jail-bound musical, and a monster truck rally that makes it to outer space. Harkness shows no loyalty to any particular layout, going from one-page splashes to jam-packed micropanels, often toying with the style in which she depicts her lead. The flexibility allows for odd flourishes that give the story a wry humor that might not otherwise come across with the song lyrics that stand in for actual text.

Greg Hunter is here, too, with a review of Aubrey Sitterson and Chris Moreno's Comic Book Story of Professional Wrestling.

Professional wrestling's relationship to the truth has long been a part of its appeal. Performers play heightened versions of themselves; matches have predetermined outcomes but take legitimate physical tolls; and the pleasure of suspended disbelief accompanies the thrill of an in-ring comeback or betrayal. Documenting the tradition’s history means contending with its layers of artifice—not just the competing accounts of various musclebound egomaniacs but also wrestling's stake in an embellished understanding of itself. So it's perhaps not just for brevity's sake that Aubrey Sitterson and Chris Moreno's new book settles for something short of history in its title. Their Comic Book Story of Professional Wrestling recognizes wrestling’s complications but isn’t always a match for them, offering critical insights and fannish boosterism in equal parts.

Sitterson, the book's scripter, locates pro wrestling's origins in carnival athletic shows that crossed the country following the American Civil War, then follows its transformation into a worldwide phenomenon at the turn of the twentieth century. Here and elsewhere, Sitterson has a weakness for excessive bolding ("Catch wrestling allowed holds below the waist, mitigating the Russian Lion's power, but he proved indomitable and was soon recognized as the world champion in England"), and his constructions are often clunky ("Much like in the carnival days, it would seem there was too much money on the table not to start at least partially compromising legitimacy for entertainment."). Even so, he makes these pages count, exploring the shady inheritances of wrestling's carnival pedigree and explaining how the tradition came to optimize its entertainment value.

Any credible understanding of wrestling is an international understanding of wrestling, and here too, the book delivers. Before surveying more recent figures and trends, Sitterson devotes a chapter to Japan's wrestling culture, from its growth after World War II to the divergent histories of storied promotions All Japan Pro Wrestling and New Japan Pro Wrestling. For the curious but uninitiated, Sitterson also clearly defines terms common to Japanese pro wrestling, e.g. "strong style" (a martial-arts-influenced tradition favoring strikes and kicks), and explains Japanese wrestling's less rigid face-heel (good guy-bad guy) binary.

Meanwhile, elsewhere:

—News. IDW president Greg Goldstein is stepping down, and being replaced by the returning Chris Ryall.

Ryall will step into his new position on December 10. Earlier this year Ryall left IDW, after 14 years, eventually taking a position at Skybound Entertainment, a comics and graphic novel imprint at Image Comics founded by Walking Dead creator Robert Kirkman.

In a press release, Ryall said IDW is "where I’ve spent the majority of my career and I consider the company and its employees like family, so I am grateful for this amazing opportunity to return.”

—Reviews & Commentary. The annual Publishers Weekly critics poll has chosen Michael Kupperman's All the Answers as its comic of the year.

—Interviews & Profiles. At Smash Pages, Alex Dueben talks to Sophie Campbell.

You’ve drawn a lot of different kinds of work, but are those the kinds of stories you like reading and watching? Or just the ones you’re drawn to telling?

It depends. I usually don’t watch or read a lot of slice-of-life stories, I watch mostly horror movies and for shows my favorites are Grey’s Anatomy and The Flash, and when I read prose it’s almost always nonfiction (I read a lot of true crime stuff), and when it comes to comics I don’t see a lot of stories similar to how I write but I’d like to read more like that. I can’t think of any truly plotless slice-of-life comics off the top of my head.

Maybe Ariel Schrag’s old books, like Potential and Likewise, which I love, they’re slice-of-life-ish but also autobio so it’s not quite the same. So I guess to answer your question it’s for the most part the type of stories I’m drawn to telling, rather than the types I read or watch. Mostly I just like stuff with monsters and serial killers in it. [laughs]

Kriota Willberg talks to Ellen Forney.

One of my points in Marbles is (the discovery) that I am more creative stable. Stability is good for my creativity. Self-care and balance is a way to be more creative and innovative. Creativity is not necessarily fueled by mood swings. Passion doesn’t necessarily come from being off balance.

The most recent guest on the Comics Alternative podcast is Noah Van Sciver, and the most recent on Virtual Memories is Bill Kartalopoulos.