This interview is from The Comics Journal #42 (October 1978)

James Madison University, a relatively isolated school in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, doesn't really offer that air of student bohemia that one would normally associate with a school Stan the Man would be likely to visit. There are no comic book or science fiction clubs, no comic-collecting professors, no comics shops, and no courses even vaguely resembling “Comic Books as Popular Culture 101.”

Which could explain why Lee’s appearance there filled less than half of a small on-campus theatre.

Nevertheless, Stan Lee was the main guest of honor at JMU's Fine Arts Festival in March, and was involved in two presentations during his one-day stay. In the first, Lee answered questions from an onstage panel consisting of: Pierce Askegren, comic collector and aspiring writer; Ezra Goldstein, editor of the theatre-oriented magazine Dramatics; David Wendelken, a journalism instructor at JMU, and myself. Lee also fielded questions from the audience during this panel, which ranged from excellent (how Lee felt about other writers switching about his characters' origins) to terrible (“How old is Jack Kirby?”). An edited transcript of the panel appears below.

Lee's second appearance put him onstage with a symphony conductor, a dance expert, and the aforementioned Ezra Goldstein, for the misguided purpose of discussing the Fine Arts Festival's inane theme, “Yeah, But Is It Art?” Fewer than two dozen people attended this panel, which consisted of a boring plethora of unenthusiastic attempts to stay on this uninspired topic.

Unfortunately, it seemed that everyone in attendance tried to get to Stan after the panel — “unfortunately,” because Lee had already twice delayed a “personal” interview with your reporter, and the time was after ten PM. Accordingly, four friends and I shouldered into the center of the grouping and set up a barrage of questions designed primarily to keep Stan from slipping out during a pause for breath. Granted, some of the questions were a bit idiotic, especially considering they came from questioners who should have known better. With the curt answers the questions were getting, though, the situation became a something/anything panic to keep the answers coming.

Gary Groth has assured me that most of the “interview” has been eradicated. Let me assure you, Gentle Readers, you are probably not missing out on anything important.

Special thanks go to Ed Via, Ralph Graves, and John Dawson, who helped formulate questions for the panel, and who also joined Pierce and me onstage for the, ahem, interview.

—JIM DAWSON

This interview was transcribed by Jim Dawson and edited by Gary Groth.

DAVE WENDELKEN: We're going to be looking at several types of questions. This week's major theme has been the question, “Yeah, but is it art?” which has changed somewhat during the week to the question of “Yeah, but is it good?” We're also going to look at some of the nuts and bolts of Marvel Comics and your favorite characters. I'd like to start off with a general question: in some of your writings, you've mentioned that comics are, in essence, a mirror that reflects our times, and my question is, what is it that Marvel Comics tells us?

STAN LEE: Actually, if I said that, I shouldn't have made it sound as though I was referring just to Marvel Comics. I think that anything that is written, and anything that is drawn, any play, any story, any visual or verbal communication between people, reflects our times, so Marvel is really just one thing with all that. As far as what Marvel is telling us, obviously, the message is so deep and profound, that we can only cover the tip of the iceberg here today. Marvel reflects the times in the sense that we are very greedy and we want our books to sell, so we only do the types of stories and the types of books that we figure the rest of the universe wants to read.

Right now, it seems that people are really interested in heroes, and have been for the last 15 years or so, because our superheroes have been the best-selling thing we've had, and they're about the best-selling comic books that anybody has, and have been for more than a decade. Those of you who have grown up in the past decade or so may wonder, “Well, what other types of comic books are there?” There's Archie, and there's superheroes. Well, in the years that Marvel, and before that, Timely Comics, had been in business, there were Western comics, there were war comics, there were romance comics, there were little funny animal comics, there were little funny people comics, there were crime comics, and police comics. Virtually any subject you could think of, there were comics about those subjects. One of the things that happened was, everything was very cyclical. One year, the Western would be the big sellers; everybody would be buying Westerns. All of a sudden the Western would stop selling. Nobody knew why, but the romance comics were very big. We would go from Westerns to romance, and a few months later, maybe a year, the little funny animals, you know, the Mickey Mouse stuff would sell. We'd start producing that type of thing. We were always following the trends.

Just as an afterthought I’ll mention, the one thing we like is we haven't been changing now for the past, decade and a half. We’ve been doing the superheroes. I don't know whether it's because the public is much into superheroes, or if we, in effect, have conditioned people to care about them. But that seems to be the biggest interest today, and it's even spilling over into films and television as you can see, just by looking around you.

EZRA GOLDSTEIN: Well, the obvious follow-up to that is, “Yeah, but is it art?”

LEE: None of us are going to live long enough to really come to any conclusions about what art is. I've been arguing that subject, or discussing it, all my life. I don't have the remotest idea, really, of what art is. I don't think that any two people have the same concept of it. Maybe the only thing you can discuss is, is it good art or bad art, and that of course is subjective also. I would say, though, and there's no way I'm going to convince anyone who disagrees, but I do feel that comic books are art, just as plays are art, and movies, and television, and sculpture and ballet and dancing are art. Maybe playing the Jew's harp and the kazoo are art. I think that anything you do that is creative is art. Whether it is good art of not depends on how well you do it. I think, for example, certainly comics presently do not enjoy the prestige of opera. But, I think there can be good comics, there can be good opera, there can be bad comics and there can be bad opera. I'd rather read a good comic than listen to a bad opera. I'd rather listen to, or see, a bad opera than read a bad comic. I think that quality is the big determination for any form of the media. I think, again, anything really can be an art, and anything virtually can be art, depending on how it's done.

GOLDSTEIN: But in a good opera, for instance, the best operas take us somewhere we can't go ourselves, and that's a rather cliché definition for art that you hear sometimes: that it shows us things we wouldn't see otherwise. I don't think that definition is applicable to comic books. Would you disagree?

LEE: I don't know how many people would have ever seen Asgard unless they read Thor, or would have ever seen a guy shoot spider webs, unless they read Spider-Man. No, I don't agree, I don't think so at all. Again, I think it depends on what the beholder looks for in the product. I'm sure that there are plenty of people who read The Hulk who get nothing out of it, and there may not be that much in it. But there are many other people who read the Hulk who feel they have enjoyed a rare emotional experience. Really, that goes for everybody. There are some people who are totally and intellectually and spiritually uplifted by reading Mike Hammer, Mickey Spillane, and some people who love Jacqueline Susann and really feel they're getting a slice of life in reading these things. Who is to say they are not?

You're getting into a discussion of pop culture vs. “culture,” with quotes around it. All my life, I've been involved with pop culture, so obviously, anything I say is going to be prejudiced and subjective. But all my life, I've been involved in art, and in illustration. I have many friends who are so-called “fine artists,” and have many friends who are commercial artists, and I'm just saying parenthetically that I personally have, in many ways, more respect for the commercial artist than for the fine artist, because commercial art is a discipline. You not only have to please yourself, but you have to please other people: a client, you have to please the public. When you're a fine artist, you do your thing; and if your thing consists of getting a monkey to dip its paws, or claws, or feet, or whatever they call them, in paint, and spatter it on canvas, and then if People magazine wants to give you a write-up, and if people want to buy the paintings, and call it art, nobody can criticize it.

The same goes for writing: the person who's a poet writes his poetry in a garret, he can be a genius, but he's doing what he wants to do, and that's easy. Shakespeare was not a fine writer; Shakespeare was a commercial writer. Charles Dickens was a commercial writer; he was the Mickey Spillane of his day. Okay, his work was good, and it lasted, and we've studied it and all. I don't want to be too presumptive, we might very well be studying the art of John Buscema some day in the future, and talking about it the way we talk about Michelangelo. I'd like to think that someday they could read one of my stories and get something out of it.

I don't think we can really predict what will last, and what's good at the moment. And, with all the joking we do about it, someday, people may pick up a Jacqueline Susann book and say, “This is a very accurate mirror of a certain phase of life in the 20th century.” They may compare it to Charles Dickens. There are some schools of thought which remind me, really, of intellectual snobbism. I mean, I see people go to concerts and listen to a fugue that they no more understand than the man in the moon, but applaud uproariously, because it was the thing to do, and the fugue wasn't all that damned good. But they'd listen to a rock opera, of they'd listen to The Beatles, or The Rolling Stones, and they'd turn up their noses and say, “Bah, this is popular music.” I really don't hold to that sort of thing.

Hope you appreciate these brief answers.

JIM DAWSON: In the 60s, you once wrote that you hoped to make Marvel Comics so acceptable to adults as well as to children, that a businessman commuting to work could be seen reading a comic book and not feel funny about it. How far do you think you've come towards reaching this goal?

LEE: Believe it or not, very far. In the 60s, when I wrote that, I wasn't getting too many invitations to speak at colleges. Right now, I'm probably as big a college speaker as anybody in the world. I guess there's a dearth of college speakers. Oh, we've come a long way. Just from surveys we've taken, when I wrote that, the median age of our readers was about eight or nine years old. Today, it's very close to 14 years of age. We actually have as many readers from the age of 15 to 25 as we do from five to 15, which to me is a very gratifying fact. In fact, I'm very surprised to find out there are still young kids reading our comics.

PIERCE ASKEGREN: Marvel has led the field for a long time in race relations; when DC had nothing but lily-white crowd scenes, black people would crop up in Marvel crowd scenes. You introduced the first black superheroes to get their own books, characters like the Black Panther. On the other hand, you've had a lot less success with other minority characters, such as women. Do you have any idea why this is?

LEE: Obviously, there are less books in the field that cater, I shouldn't say cater to, but that feature heroines. They don't sell as well, they don't sell as many copies. However, as with the books for older readers, they do sell more than they used to. I think what is happening is females are becoming more attuned to comic books. It just never was a thing for girls, by and large. Girls would never buy toy soldiers; they played with dolls. Very rarely would you see a parent buying toy soldiers for girls years ago. I think a lot of that is changing today. Even in grade school, they are teaching boys cooking today, and shop to girls. So, possibly later on, we'll have as many female readers and at that time we’ll have as many female characters.

We're trying now: we have Red Sonja, we have Spider-Woman, we have Ms. Marvel. Also, I've got to find artists who can do justice to a strip featuring girls. There aren't that many around, because for years we haven't had that many strips. I hope I've answered your question.

GOLDSTEIN: While we're talking about stereotypes, in retrospect, do you feel badly about how you went along with the Red Scare? In one of the comics I read, there was the Gargoyle, who was this horrible commie, and as soon as he transformed into a normal person, he realized that he would no longer be a communist.

LEE: Why did you leave Cincinnati? I think that Marvel Comics is never having to say you're sorry. It was really a more naive time, in those years, and I'm a product of the times. I'm a media child. What happened was, the comic books you're referring to were done at a time when our government was telling us that we were the good guys, and that the communists were the bad guys. I had been conditioned. During World War II, we were told that we were the good guys, and the Nazis were the bad guys. I believed it, and I still believe it. And virtually every comic book we produced… well, I was away at the army for a while, but before I went and when I came back and while I was gone, the books that the other guys did, all featured Nazi villains. You just couldn't make it as a villain unless you were a Nazi.

A few years later, when the word came down from D.C., that the commies are the bad guys, I just acted like one of Pavlov's dogs. Then came Vietnam, then came student protesters, then came a whole change in the country. I think you'll find that at that point we got off the kick. But I do have to plead guilty to what you said at the time you said it.

DAWSON: Neither of the two television adaptations of Marvel characters, Spider-Man or the Incredible Hulk, was entirely faithful to the comic book background -of either character. In the Hulk's case, the entire origin sequence was changed for television. As the creator of both of these characters, what is your opinion of the way the shows are being handled?

LEE: Well, that's a big question, too. I would prefer it if the shows were handled a little differently; in fact, I serve as a consultant of the shows. They are making changes now; we have been working on that. In order not to drag this on forever, I’ll answer you very concisely. I think the shows are not as good as they could be, but I think they are not as bad as they might be. They're sort of right down the middle. Now, I think that the character of the Hulk is so strong that even though the shows have been less than ideal, the first show got a tremendous rating, the second show got even higher ratings. CBS and Universal are tremendously pleased and they feel they have a hit. I think the future shows will be better, we're playing up the characterizations more. They also had high hopes for the Spider-Man show, I think you'll find that comes across as being a little more juvenile, mainly because of Peter Parker as a college student; there is no way to make the show seem as mature, because it is on at 8:00. They can't even suggest anything with sexual overtones or anything like that. Not that the Hulk is a pornographic show. It's on at 9 o'clock, so they can get a little more meaningful relationships.

ASKEGREN: Comic books are the only medium that has to be censored before it reaches the stands, and I was wondering if you feel that working under the Code stifles creativity? When Spider-Man had the famous three-part story that involved a sub-plot with Spider-Man's best friend hooked on something, you ignored the Code —you released them without the seal. Would you allow someone to do that again if he felt strongly enough about it?

LEE: I never really ignored the Code; I just opposed it in that particular area. What happened was, with the drug story you're talking about, I had received a letter from the office of Health, Education and Welfare, or HEW as we aficionados know it, in Washington, and the letter went to the effect that, recognizing the great influence that Marvel Comics has on the youth of the nation, we'd appreciate it if you would do a story admonishing young people, warning them about the dangers of drug addiction, which seemed to me like a pretty laudable statement for a story.

Well at Marvel, I don't like to hit people on the head with a theme. The minute anyone realizes, “this is a story telling us not to take drugs,” the whole message will be ineffectual. Nobody wants to be lectured to. So, I made it almost a subliminal thing. In a regular story, where Spider-Man will bring down the Green Goblin, in the course of the story, one of his friends had overdosed or something and was about to jump off a building and Spider-Man saved him. He gave him a big lecture: “Hey, you shouldn't do that.”

Then we submitted it to the Comics Code, and they said, “Hey, you can't print this, you're not allowed to mention drugs.” Jeez, I’m not telling people to go out and take 'em, I mean, read the story! They said, “Doesn't matter, read the Code! Thou shalt not mention drugs!” I said, all right, then we won't publish the book within the confines of the Code, and we left off the seal for three issues, because it was a three-part story. Strangely enough, the world didn't come to an end and we've remained within the Code, and now We have the seal on again.

I’ll tell you a funny story about that. Sometimes you can get overzealous with censorship. We submit all our books to the Code authority — just to make sure that there's nothing that slipped by us that might be harmful to a kid six months old. We had a Western story years ago called Kid Colt and in the story there's a shot where Kid Colt is firing a gun. I forget what the story was, but in the panel — you know the way you draw a guy shooting a gun, he's in profile, and he's holding the gun like this and shooting it, and from the barrel of the gun there's a puff of smoke, and a line shooting out which denotes the trajectory of the bullet. That page was sent back to roe and they said you've got to change the page, it's too violent. I said, “What's the matter?” And the explanation I was given was the puff of smoke was too big. If we made the puff of smoke a little smaller, it would be less violent. Ever anxious to contribute to a campaign of less violence, or non-violence, I immediately whited out the puff of smoke, drew a smaller one, and you’ll be happy to know that the younger generation was safe.

But to answer your question you'd thought I'd forgotten, I don't think creativity is really limited. I think, if you're creative it makes it more fun. Again, remember what I was telling you about fine art and commercial art. To me, if you are a creative person, what kicks do you get just doing what you want? A monkey can do what he wants. To me it' s fun to have a lot of obstacles, and to figure out, “How am I going to do a story that people might buy or enjoy, despite these obstacles?” It doesn't really hinder us very much.

ASKEGREN: One interesting thing is, just a few years before you did that story, DC's first story about a character called Deadman featured cocaine smuggling, and they got it right through. They didn't have any trouble at all.

LEE: I don't know the story you're referring to, and I don't know if you have your time confused or if that's another instance, but right after we did ours, DC did a drug story, and then the Code — oh, I didn't add, the Code finally changed their policy after our story. We got all sorts of congratulatory letters from teachers, ministers, government agencies, and so forth, so they allowed us to use drugs. The minute they did that our competitor had a big cover with a guy shoving a needle in his arm. Some people really aren't noble and subtle.

WENDELKEN: Let's have a few questions from the audience before we come back to the panel. (All of the following are unidentified audience questioners.)

QUESTION: What do you recommend for a person who is interested in a career in comics?

LEE: Don't ask me how to write for comics, because I don't know how to answer it. It is almost impossible for an amateur to become a comic writer the way things are today. But, as far as artwork goes, that I can answer easily. We're always looking for good artists, but the artwork that is submitted has to be really as good as what is being published today. Because, with the press of our schedule, we don't really have the time to train people. But if somebody can really draw, all you have to do is send us a few samples of your work. The best way to do that is, now I don't know the exact measurements, but we work 50% up, whatever size the comic book page is, the artists draw 50% larger. Draw the artwork 50% larger, do it on sheets of illustration board, flexible illustration board, I think it's called two-ply, and do two or three pages in pencil, don't ink it, all we care about is how well you pencil a strip. Just take any one of our characters you might be interested in, you can make up your own character but it's silly to, because we're more interested in how you draw our characters. Take Spider-Man, Thor, the Hulk, I don't care.

Dr. Strange, Captain America, and make up your own little visual story, anything you want. He walks into a building, a guy points a gun at him, and kicks him out on his head, he runs around, kisses a girl, anything, just so we can see how you draw. Send those pages in ten Jim Shooter, editor, Marvel Comics, if you forget his name he'll get it even if you say “Editor, Marvel Comics,” but he'll be annoyed you didn't know his name. And you’ll get an answer within the next decade or so. I suggest you send photostats in case they get lost. But, seriously, if the stuff is good, Jim will probably contact you. There's really a shortage of fine artists in the business.

QUESTION: When will the Silver Surfer book be released?

LEE: I'm glad you asked that. The book is The Silver Surfer, it'll be published by Simon and Schuster, and it'll sell for the ridiculous price of about 10 bucks, full color, a hundred-page original Silver Surfer story on the finest quality paper. I just finished it a few days ago, Jack [Kirby] has drawn it. As a matter of fact it went to the printer yesterday [March 22, 1978]. It'll probably go on sale in September or sometime this Fall. And, while again I may be a little prejudiced, I strongly recommend it.

QUESTION: Mr. Lee, since the creation of Spider-Man, which will probably never be equaled in the course of history…

LEE: You're a great man.

QUESTION: …what's your next greatest achievement?

LEE: I don't think it's for me to say. I don't really know of the comics characters I did. And of course I've got many other achievements. But of the comic characters I've done I don't really know which is the best. I guess you could tell … being a crass commercialist, I would have to say maybe the Hulk is the next best one because he's the second-best seller, you know, so if you go by sales figures that's him. I have a soft spot in my heart as well as my head for the Silver Surfer. And I like Dr. Strange. Maybe I like him because they're about to do a television series of him, I don't know. I'd like to think all of them are tainted with greatness.

QUESTION: What spurred the Spider-Man and Fantastic Four cartoons?

LEE: What spurred them? Sheer greed. Somebody came up to the guy who was then the publisher, and said, “Hey, I wanna do some cartoons of your characters, and I’ll give you a couple hundred bucks,” and he pounced on it. And, we were very unsophisticated. I say “we” — that's the editorial “we,” I really mean our publisher. He was very unsophisticated in manners of this sort. And he didn't worry about the contract; nobody had ever asked to do cartoons of any of our features, and we were so excited. We got absolutely no editorial control over those cartoons or anything, but he loved the idea of being paid a few hundred dollars for each one, and he said okay. The next thing we knew, they were on the screen. That was it. They're still being shown around somewhere.

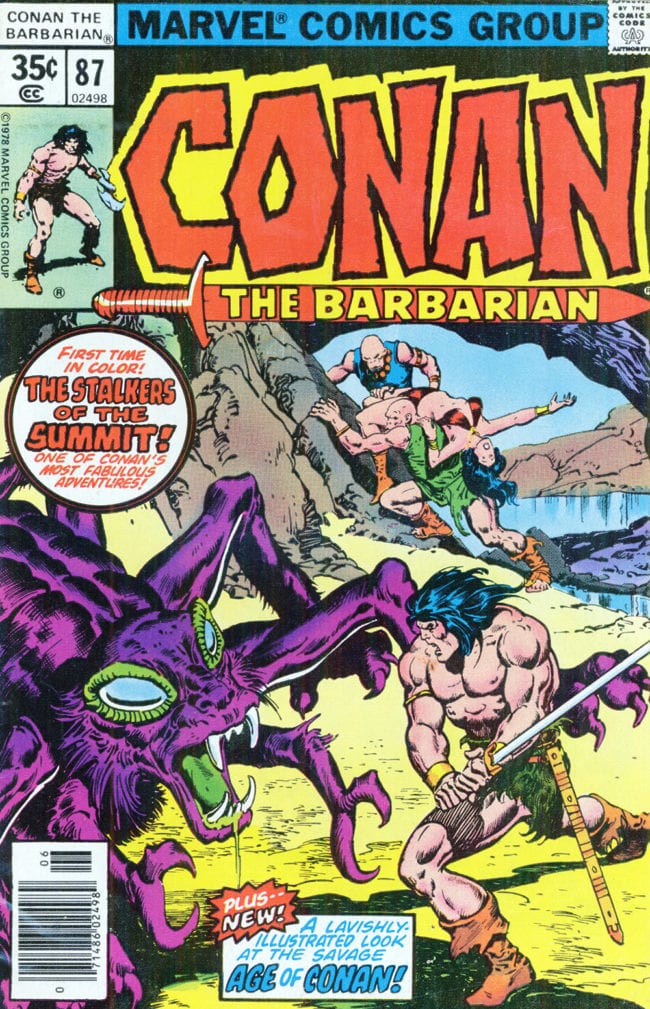

QUESTION: When did Marvel start publishing Conan?

LEE: Oh boy, you're asking the wrong guy. I've got the worst memory in the world. I think… must have been three or four years ago. Maybe somebody here would know better than I.

DAWSON: It was 1970.

LEE: You see that? NINETEEN-SEVENTY?

DAWSON: Yeah.

LEE: We've been doing it for eight years?? [Laughter] That's incredible. I really would have thought three or four years. Wow.

QUESTION: Wasn't the original artist on Conan Barry Smith?

LEE: One of the original… yeah, I think he might have been the original. Yeah.

QUESTION: Do you know what happened to him?

LEE: Yeah: Barry was a guy I was very proud of, he was one of my protégés. He came up to the office once, as we mentioned before, with samples. He was in the city so he brought them up personally, and they were like a very rough imitation of Kirby's work. But he was a kid then, I think maybe 18 years old, and for a kid his artwork had a lot of power, excitement and creativity, and I said I wanted to use him. And everybody in the Bullpen thought I was crazy, they all thought, “Aah, it's too rough, and it's just an imitation of Kirby.” It was one of the few times when I turned out to be right. We used him, and I never saw a guy improve so quickly; with his second or third job, he was as good as almost anybody we had.

But to answer your question as to what happened to him: he's a funny guy, he doesn't really want to think of himself as a hack artist, and he'd love to be a businessman and have his own thing going for him. So he stopped doing strips and features for us, or for anybody in comics, and what he did — he'll do an occasional job for us, but nothing on a regular basis — and mainly what he's doing, is printing posters of his work, and he's selling them at comic book conventions and through fan magazine ads and stuff like that. And, I really don't think he's making as much money as he would make staying in comics, but I think he's somehow getting more satisfaction, and feels he's doing the right thing.

QUESTION: Do you think he did the best Conan issues?

LEE: I really hate to give an answer like that, because again that is such a subjective opinion. Certainly some of the things that John Buscema has done are gorgeous. It's like saying, “Who's your best artist?” or, “Who's your favorite artist?” and it's a question I really hate to answer. He certainly did turn out some beautiful issues, I’ll say that.

QUESTION: What's your favorite story you ever wrote that was published by Marvel?

LEE: You know, I really don't know. I don't think in those terms. I can tell you there are some stories I've forgotten and some I remember. And I think, mainly, as with our characters, my favorite ones seem to be the ones that are the most popular, and I figure if everybody likes them they've got to be my favorite. Almost every time I lecture at a college, some guy will say, and I love the sound of it, “Why don't you reprint the Galactus trilogy?” You may remember we did a story in the Fantastic Four with Galactus and it introduced the Silver Surfer, and I've been asked about that so much that that's the first one that comes to mind. So I would have to say that's my favorite. But in all honesty, I don't even remember it that well. You know, I'd have to go back and re-read it. As I say, there's probably something wrong with me, because I know most people are always thinking in terms of the best and their favorite, and it's something that I almost never think about. Once I've written something, it’s finished and I forget it pretty quick and I'm just on to something else.

QUESTION: When is the “What If Conan Walked the Earth Today?” issue of What If…? coming out?

LEE: I think Roy Thomas is working on that. I'm not sure. I gave him the book to do and he selects the things himself, and I have a feeling that he's working on it. Because I did hear him mention it.

QUESTION: Roy Thomas, particularly in The Invaders, is getting on a kick about switching around origins, and making-, them up. I was wondering how you as a writer of Captain America felt about the way he recently decided to give Captain America no past.

LEE: Well, in all honesty, I hate it when people change the origins and the various little institutions and schticks that I've given these characters and stories. But I try to be fair about it. It isn't fair, I think, for me to control something that I'm no longer writing. When I wrote the scripts, I did them my way. Of course, I'm dealing with people who are creative writers, and I try to get the best work out of them. It's very hard to get the best work from a creative writer if you're giving him too many orders; he begins to resent it. And, I have a problem in that a lot of guys feel, “Gee, Stan started most of these strips, his name's on all the books, and he makes all these speeches— how are we ever gonna get any fame around here? He hogs the spotlight all the time.” So I try to bend over backwards as much as possible and let the fellas do what they want. I don't know if it's healthy for a whole line of stories to be the product of one guy's thinking. We have a lot of talented people, and I have a feeling maybe if they all could do their own thing, some of what they do will stick and be good, and it'll give new life and new excitement to the line. If they all try to follow my style, the stories might get a little bit tiresome after a while. But from a personal point of view, of course, I hated it on television when they changed the origins of two characters. I hated it when Conway killed Gwen Stacy in Spider-Man. I hated it.

(At this point the proceedings shift back to the onstage panel.)

GOLDSTEIN: When you started out with the Marvel characters in the early 60s, you introduced intelligence to the comic books — everybody thought you were crazy and you'd lose your audience. You obviously didn't lose your audience, and now you're considered somewhat of an expert on communicating with teenagers. Can you sum up… well, just how do you communicate with a teenager? I'm very curious.

LEE: Reluctantly. No, actually —and this is something that I've spoken about — I think the most important thing in communicating with teenagers —and this holds true for young people and old people, I think age has nothing to do with it — I think the most important thing is honesty. That may sound silly when you're writing comic books, but for instance, when we made a mistake we admitted it. Well, we had to, we made so many mistakes.

I'd like to feel that our readers feel our stories may be dull, or repetitive, or old fashioned, or they like them or don't like them, but at least we're being honest in what we write, and they really represent the way we feel. In our little editorials and letter columns, we try to level with them… I try to do it in my dumb little column — the “Soapbox.” I find that is really the most important thing in communicating with somebody. Let them feel they can bank on what you're saying.

And I think you've got to have a sense of humor. I have gone to five million dinners and lectures and heard speeches, and I have heard some of the most intelligent and well-informed people speaking and they just totally put the audience to sleep; they were so damned pompous and took themselves so seriously, you just know this guy never smiles. So, I would say, especially with kids, that honesty and some semblance of a sense of humor are probably the two most important elements in not having them throw stones at you.

DAWSON: Heavy Metal is a comics-type magazine that was introduced a year ago which is aimed at an older readership than the comic book market but still uses a comic book format. Has there ever been any plan at Marvel to produce a magazine of this type, or will the Marvel magazine line always be directed toward the same market as the comic books?

LEE: That's a big frustration of mine. We were gonna do Heavy Metal before the Lampoon did. It was offered to me first. The people who did it are friends of mine. I wanted to do it very badly, but did a lot of soul-searching, and came up with the conclusion that, good as it is, and some of the artwork is beautiful —better than the stories— you can't sell a book like that without a generous helping of sex. Gotta have a lot of nude men and women and what not. I personally am not a prude, but we're aware that many young kids read Marvel Comics. And we just didn't want to take a chance on a book which a lot of kids would see and see that it's done by Marvel Comics and perhaps see my name on it and bring it home and their parents would say, “Aha, so this is what Marvel has gotten you into.” And I'm sorry, because, I would like us to be doing that type of thing, but until I can find a way to do it so that whatever we do would be suitable just to bring into anybody's house, we've got to give it a little more thought.

What we are trying to do as a step in that direction is do some magazines to sell for a buck fifty or two dollars on the same kind of paper as Heavy Metal. For instance, we'll be doing a book on the Beatles, which is going to be an expensive comic. We're doing one on Elvis Presley, we're going to do one on Led Zeppelin, the Bee Gees, and Frampton. We're doing versions of various movies that'll be done expensively. We're going to do Meteor, there's a new show coming out called Galactica, and we're going to do an expensive version of that.

I spoke to Ralph Bakshi the other day on the Coast. He's doing The Lord of the Rings. He's doing the longest animated movie that's ever been done. It's a three-parter based on The Lord of the Rings. And we made a verbal commitment that we would do the comic book version of it. That'll be a series of very expensive comics, and I think it'll be beautiful, 'cause I'm not going to do it until we find the right artist. And those of you are familiar with Frank Herbert's Dune trilogy, we're going to see about doing Done also in a quality edition.

So, that's the direction we're trying to go now, until we can figure out another alternative.

ASKEGREN: Marvel exploded in the early 70s, along about the same point Roy Thomas took over as editor. You just erupted into scads of titles, and people who had been doing inking suddenly started penciling for you, and, simultaneously with this, some people like Neal Adams and Jim Steranko left. Do you feel this has hurt the line any? Do you feel there's strength in diversity? Just this sudden outgrowth — for a long time Marvel had just been a handful of closely knit magazines.

LEE: I don't understand—do you mean that Adams and Steranko leaving hurt the line? Or the fact that there are a lot of books?

ASKEGREN: I meant the explosion as a whole.

LEE: Well, it's a funny thing. We could do better books, obviously, if we did less books. If we were to lop off half of the titles that we have, and just produce half as many, I think the books would all be better. Of course, we'd fire half of the writers who aren't as good, and fire half of the artists who aren't as good. Sometimes you have to make decisions. You have to decide between a pure business decision and being a human being. A lot of the guys working for us have been with us for many years. Very tough to just say, “Hey, you're not as good as Charlie, you're fired.” A lot of the books we produce, we are aware, aren't all that good, but they're keeping guys working. And we think we're big enough and maybe we make enough money that we can afford a few who don't do as well as others.

Then there's another problem. We're always getting letters from readers, and the same in college lectures, the question is always, “What are you coming up with next?” “What new books do you have in the works?” “What new heroes, what new properties?” And it seems to me that it doesn't matter what you do, really—we could be turning out 40 masterpieces every month, and people are still going to say, “Aaah, the same thing every month, when are we going to bring out some new titles?” So it seems that we virtually have to keep producing new things just to keep the readers happy.

(Back to the audience now for a few more anonymous questions.)

QUESTION: Would you comment on the effectiveness, or the impact of comics as a medium of communication, and relate it to some of the other media of communication?

LEE: I have learned over the years that comic books are probably one of the most effective methods of communication known to man. When I was in the Army, I was one-ninth of a whole Army corps. My job was training films and instruction manuals. And I was with eight other guys like Saroyan and so forth; I was the token kid. They were all older and more famous. I didn't really know what I was doing at the time, but the army does some crazy things.

Anyhow, we were given some of the most difficult instructional projects of all. And it was our option as to whether we'd get our message across by doing a movie, doing a magazine, or a manual, or what. One of the more difficult projects involved finance, and this was thrown at me, which was typical Army thinking because it was a subject 1 knew absolutely nothing about. They were having a big problem, they weren't training payroll officers quickly enough and this was a big morale problem, because those guys over in the foxholes overseas, getting shot at all day, weren't even getting paid. There wasn't payroll office in that vicinity, because there was a shortage of payroll officers. Can't get your pay without a payroll officer.

So my job, and it's out of Mission: Impossible, my task was to find a way to re-do the training manuals so they could train payroll officers faster and get them overseas. I read these manuals. J was first going to do it as a movie, but then I realized that a movie has the greatest initial impact of any form of communication—you see the picture, you hear music, you see motion, it's bigger than life, it gets you. But it has a few shortcomings. You can't carry it with you. You can't study it at your own speed. If you're a little bit slow, and it's going too fast for you, you miss things. If you're very bright, and it's going at the average level, you get bored because you're ahead of it. If there's something you've missed, it's not very convenient to always find a way to see it again. And so forth.

A comic book is about the greatest —I mean something in the comic book format— is really one of the greatest ways to get a message across. It has the pictures, it has the words, it's visually interesting. Okay, the pictures don't move, and it doesn't have music or sound, but that's not essential. That goes to emotion more than to intellect. Depending on how it's done, it can be very crisp and concise and explanatory.

Well, I created a little character. I called him Fiscal Freddy, and I made him the hero of this book. He ran through all these dull payment forms, illustrating how to make them out; the upshot of it is that we were able to reduce the training period that was required to process a payroll officer from six months to six weeks, by using these comic books. And the colonel in charge of this thing was made a general, and I received a commendation. I don't like to brag, but I like to think I won the war single-handed.

Anyway, all my life I have found, I won't bore you with the details, but I've used comics in many advertising campaigns. They are a tremendously effective method of communicating. They're as good as any I can think of. They can be used for propaganda, they can be used for instruction, they can certainly —and they are— in use as entertainment. There's something about them that grab a reader…

One last very brief example, and you can try this yourself. Go to any house where a kid is watching television. It can be the most exciting television show in the world. And if there's a coffee table between the television set and the viewer, just drop a comic book —hopefully a Marvel comic book— on the table between the kid and the screen. And it won't be many minutes before he will turn away from the screen, pick up the book, and start thumbing through it.

One other effect: comic books are like the last weapon left, defensive weapon, against encroaching “televisionitis,” which is making non-readers out of a whole generation. Most kids, if not for comics, wouldn't read anything at all. By reading comic books, they learn to equate enjoyment with something that's on the printed page, which psychologically is a very healthy thing. They always go on to other things. There's nobody in the world who just reads comics. Once he becomes a reader to the exclusion of other things. And if I speak any longer, this will make a whole series.

QUESTION: I noticed your brother's name on the cover of Captain Britain. What else is he doing now?

LEE: Mostly he's working with the books we produce for England. We still do four or five weekly comics. Over there comics are primarily done on a weekly basis in a tabloid form, and most of our things over there are reprints, we just reprint our regular books and ship them over. Larry is the guy who gets them all together.

QUESTION: Most of your popular characters have either physical or emotional flaws. Do you think that's why they're popular?

LEE: Yeah, I think that's one of the reasons. In the beginning, when we started doing the characters, my feeling was that I really hated the way superhero as had been done previously: they were all perfect. And it made for one-dimensional characters. In the old stories, there'd be a crime, the hero would come and say, “Oh, I've got to catch the Joker,” at the end of the story he'd catch him and that was the end. I'm much more interested in people than I am in things. To me, the most interesting story is when you care about the characters. In fact, I'm the worst plotter… I've written five hundred million plots in my career, I guess, but I hate doing the plots. They bore me sick, and usually I will pick the simplest plot in the world. What I'd rather concentrate on is the personal problem. Maybe Daredevil wakes up one morning and finds that he's losing his radar sense, or he's falling in love with another girl or something will happen with the jealousy angle, maybe somebody's lost his money, or he has to make a decision — if he saves his friend over there, somebody else will die over here, if he rescues this person, something will happen to his friend—how does he work that out. That interests me. But at DC, the opposite is true. The way they build their stories, they'll spend most of their time saying, “This will be the crime we'll have, and these will be the clues we'll plant, but nobody notices this last clue until the end when somebody spots it.” They spend most of their time thinking about that. And, to me, the characters are just one-dimensional.

So giving our characters flaws and problems and things to worry about is definitely intentional, because to me it makes them far more interesting. It makes them more like me. I'm really not perfect, I too have faults.

QUESTION: Do you have any information on how the Conan movie is coming along?

LEE: No, I don't really know too much about it. I heard that Arnold Schwarzenegger had been signed to play the role, so Conan will not be too anemic looking. Roy Thomas was supposed to have done an original script in conjunction with some guy I know whose name escapes me now, and I think that they got some other writer with a little more movie experience to do the final script. As far as I know, things are moving along. Movies take a lot of time but I think it's still coming along, they're still planning to produce it.

ASKEGREN: Are you buying your own animation studio?

LEE: We were going to buy it, but we went into a partnership with them instead.

ASKEGREN: Which studio is that?

LEE: It's the DePatie/Freleng studio — they do the Pink Panther, Dr. Seuss, and Mr. Magoo.

ASKEGREN: Freleng had a lot to do with the old Bugs Bunny…

LEE: That's right, that's right. They're geniuses, and we've already started doing the Fantastic Four series, and it looks like it'll be great.

DAWSON: Will they be new stories, or will they be adaptations?

LEE: Well, I don't know. We're using the same villains, some new villains, whatever we think of. We'll borrow from the old stories, and we'll add some new stuff, too.

DAWSON: Has Kirby expressed any kind of interest in coming back to the Fantastic Four?

LEE: I haven't discussed it with him, but, since he'll be doing the Fantastic Four television show, maybe he will. All the guys want him, you know, every writer we have would love him to draw for them.

DAWSON: Right. This is a kind of weird question, but…

LEE: I’ll give you a weird answer. [Laughter]

DAWSON: Okay. Conan's up to #87 now and — you've already got reprint books of the FF, Spider-Man, Captain America, the Hulk, The Avengers — is there any chance of getting something like “Marvel Barbarians”?

LEE: You want to know something? I never thought of it. Why not? [Gets out little brown notebook and writes in it.] “Conan reprints,” right? I don't know what the title will be, but we’ll see what we can do…

DAWSON: Yeah, because Spider-Man got his way back when, and Conan is up to almost his 100th issue by now. Also, do you think that science fiction at Marvel has gone down for the third time, or, in light of the popularity of Star Wars and Close Encounters, do you think there's a chance of something like Unknown Worlds coming back?

LEE: I have no great desire to bring it back. If some of the editors want to do it, I’ll try it again. You see, what it is, the readers really prefer stories about characters, and no matter how good the stories are, if they're just isolated stories I don't think they'll make it. So, I don't particularly want to do it, but if Shooter or somebody wants to do it, I’ll let 'em do it.

ASKEGREN: Bring back Speed Carter, Spaceman.

LEE: Is that one of ours? Oh, yes. [Laughter]

DAWSON: You mentioned this afternoon that, the Silver Surfer, if it was popular, would be coming back as a comic book series…

LEE: Oh yeah, once I've done the book… I wanted nobody to do the Silver Surfer until the Simon and Schuster book is finished. Once the book is published, then I don't mind if someone else does it. We may do it as a regular book.

DAWSON: I know you may not have talked to anybody specifically, but do you have anybody in mind…

LEE: No, I haven't even thought about it, but I’ll try to pick the best people I can, of course.

DAWSON: There's been a lot of fan interest in the Prisoner… Mediascene's printed pages from the comic, and also the show is back in syndication now…

LEE: I may bring it back. What happened was, I had Jack do it and I had Gil Kane do it… I had Gil Kane do it first, then Jack, and I didn't think either of them… they both did good jobs, but when I looked at the artwork it didn't look that interesting. And I said to myself, maybe it's the kind of script that just doesn't translate well into comics. There was nothing much happening, just a lot of faces and walking around. But now that it's back on television, back on educational TV, maybe we'll consider doing it again.

DAWSON: Marvel has discontinued its entire line of horror comics. Do you think these books failed because they all went reprint, and do you think that an all-new horror comic, such as Tower of Shadows, Chamber of Darkness were in the beginning…

LEE: I think we could make one work, but I'm really not that interested in them, because in order to make 'em work you've got to get real horrifying stories, and then you're gonna get parents saying, “You’re getting too violent, too horrible,” and I don't think I need that kind of headache. I really much more enjoy doing the superheroes, doing stories about people rather than just about things.

DAWSON: That leads into two other questions. The first one is, The Washington Post Magazine ran a front-page feature on the death of romance comics. There are no more from anybody any more. Were they selling that terribly? They were really popular in the early years…

LEE: No, I just wasn't interested in them. I have written probably more romance stories than any living human being, and I'm just bored with them after years of it. Again, if we start getting more female readers, we may bring some back, but There aren't that many good romance artists, and we're gonna have to wait until we pick up a few before I’d consider doing it. A romance strip that isn't drawn magnificently just looks kinda cheap.

DAWSON: There have been a lot of complaints, mostly from the real hardcore fans, about the plastic plates that are being used to print the comics…

LEE: We have no control over that. The engraver uses those, and that's all that he has to use… it's a case of they either use those or we don't get the comics engraved.

ASKEGREN: Do they use those on the black and whites, too?

LEE: You know, would you believe, I honestly don't know. I don't know much about the technical end of it. Once the book goes out to the engraver, I don't know what the finer points are. I’ll find out.

DAWSON: Plus you said this afternoon that there was a chance your new, most expensive magazines would be on slick paper…

LEE: Oh, they'll be different, they'll be using a different printing process. (Holding open the Origins of Marvel Comics book and a 35¢ comic and using them as examples) This is called letterpress, the $1.50 are like this. This is called offset; it's a totally different printing process.

DAWSON: Is there any chance of a slick paper magazine coming out?

LEE: Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Good chance.

DAWSON: Any ideas in mind for that?

Yeah, we'll be doing our movie versions on slick paper, we'll be doing Tolkien on slick paper, we'll be doing Dune on slick paper, all those kinda of books.

ASKEGREN: Isn't Howard the Duck going over to that, too?

LEE: We may be doing a Howard the Duck on slick paper, too, yeah, and a Conan special on slick paper. We have a lot of things we want to do.

DAWSON: DC, as you may know, is going over to 50¢ in June. It seems inevitable that you’ll follow suit…

LEE: No, I have no plan to. Unless they do so well and the kids buy nothing but their books and we lose a fortune, then I’ll do it, but I don't expect that to happen. I have a feeling that we'll sell more books than ever, and they're going to fall flat on their face. But, you know, I have no way of knowing.

DAWSON: Everybody I know thinks this is a stupid question but is there any chance of your going to a shorter format, just to undercut sales? Such as an eight-page story in a 20-cent comic? [Convulsive laughter from all parties.]

LEE: You know, it's not that bad a question. I hadn't thought of it.

DAWSON: It would be less than half price…

LEE: Don't print this in the fanzine. I don't want Jenette Kahn to read it—I want to think about it a little more.

ASKEGREN: Yeah, you could give them away in cereal boxes…

LEE: Yeah, it's not a bad idea.

ASKERGEN: This is on a little bit more immediate level. In some pieces Marv Wolfman has had published in a couple of fanzines, he mentions in passing that you wanted to make some changes in the Spider-Woman character…

LEE: I haven't even read the damn thing. [Laughter] I may have said it and I don't remember, maybe it was the costume or something.

ASKEGREN: What type of thinking went into that character — was it just a name that popped up?

LEE: Yeah… you know why we did it, really? I suddenly realized that some other company may quickly put out a book like that and claim they have the right to use the name, and I thought we'd better do it real fast to copyright the name. So we just batted one out quickly, and that's exactly what happened. I wanted to protect the name, because it's the type of thing someone else might say, “Hey, why don't we put out a Spider-Woman, they can't stop us.”

ASKEGREN: DC's got a Power Girl…

LEE: Exactly, and I'm pretty annoyed about that. In fact, that reminds me, I've got to ask the lawyer— she's supposed to be starting a lawsuit about that and I haven't heard anything. I don't like the idea…

You know, years ago we brought out Wonder Man, and they sued us because they had Wonder Woman, and me, being a gentleman [Laughter], I said okay, I’ll discontinue Wonder Man. And all of a sudden they've got Power Girl. Oh boy. How unfair. Yeah, I’ll remember to check into that one. [Jokingly] Heads'll roll.

ED VIA: I'd like to ask you a question about films made from Marvel comic character a. So far, most or all of them have been TV movies. I was wondering, is there any chance of a major feature film…

LEE: Yes.

VIA: …with top-name writers, directors, cinematographers, etc.?

LEE: Yes. We have a number of people who are speaking to us now, and we've been so busy working on the TV stuff that, you know, we keep putting them off. There are people who want to do a number of our characters as feature films, and I would say sooner or later we'll go ahead and do them.

VIA: The end result seems to be so much better in a feature film than in a TV movie.

LEE: Well, there's two different ways of looking at it. You do a feature film; okay, it could be a blockbuster like Star Wars … or it could be like Doc Savage—it's here today, gone tomorrow, goodbye. The television show, if it catches on, it's there week after week after week, and everybody sees it. A good television series is the best thing you can have, 'cause it's very unlikely you're going to come up with another Star Wars. Now Superman, my God, they're spending 25, 30 million dollars on that thing. It could end up being another Dino DeLaurentiis King Kong. [Laughter.] I would hope if we do any we won't do a $20 million one. I'd like to do a feature film, get somebody to do it for about two or three, four million dollars. I don't think you have to spend that much money. I think you need a good story, good actors. But anyway, it won't be my decision, that'll be the decision of whoever produces it.

DAWSON: You said you wanted to talk to the man who saw the Bionic Woman…

LEE: Yeah, you said that our plot was the same as the Bionic Woman? [This refers to the first regular episode of the Hulk TV series, and the program's similarities to a Bionic Woman script.]

JOHN DAWSON: It was exactly the same except in the Hulk instead of drugging the drink, she had this dart in her hand…

LEE: But it was the fighter who wanted to be a contender, and it was the cage up in the…

JOHN DAWSON: Yeah, the cage was exactly the same.

LEE: All right, there'll be a little talk about that when I get back to New York.

ASKEGREN: Whatever happened to the idea of Marvel publishing The Spirit reprints?

LEE: Well, Jim Warren was doing them.

ASKEGREN: Well, Warren cancelled it and an underground comics company picked it up…

LEE: I don't know… I think since it's already been done, what the hell, so we'd be reprinting reprints…

ASKEGREN: You've been quoted as saying that's one of the few comics series you really admire.

Lee: Hell, it is, and I do admire it, and Will Eisner is a very, very good friend of mine and I'm a big fan of his. But, as I say, since Warren's already done it, I still have to look out to make sure we can sell books, and it's very possible that our readers, anybody who would want to buy it, has already bought it. So I don't know that I'd be able to really do that. If he wanted to do a new Spirit, I'd be very happy to do it. Very happy.

ASKEGREN: How are the Hanna-Barbera books going over?

LEE: Not great… they don't seem to fit into our line that well. We were hoping to capture a lot of younger kids, but… they're doing all right, but they're not setting the world on fire. I just looked at some figures before I came here, and I think the sales are starting to pick up, so maybe it takes a while, maybe they'll start…

ASKEGREN: Didn't pretty much the same thing happen with your Western books in the late 60s, when you tried to do a lot of new Westerns and nothing really went?

LEE: Yeah.

DAWSON: How about the Burroughs books? Are they…

LEE: They're doing pretty well, Tarzan and John Carter, they're doing pretty well.

ASKEGREN: Is there any chance of a Burroughs magazine, with the larger format?

LEE: Yeah, yeah there is.

ASKEGREN: Burroughs is pure comic book…

LEE: Y'know what our problem is? there's 500 things we could do with them, and there are only so many hours in a day, and we only have so many artists and so many writers.

ASKEGREN: Cancel a couple of Spider-Man's books. [General laughter.]

LEE: We can't. Spider-Man sells too well.

VIA: Carmine Infantino is doing a lot of work for you now, but it seems that every month he's on a different book. Is that the way he wants it, not -to be pinned down to a regular series?

LEE: I would guess not, but I really don't know, 'cause Jim Shooter is the guy who gives out the assignments. I would have to ask Shooter what the reason is. Usually the reason for that is deadlines. A guy is late on one book, or somebody else broke his arm, and somebody has to go up to him and say, “Hey Carmine, you’re fast, how about you filling in on that and we'll get somebody else to do yours.” It's like falling dominoes; when somebody else misses a date, “How about you doing that, and you do his, and you do his,” and we're always shuffling for that reason. It's one of the reasons we can't do too many new titles, because we have trouble Just doing our old titles on time.

ASKEGREN: I noticed Crazy didn't become a success till you divorced it from the typical Marvel line, brought in Paul Laikin and his people. Couldn't Gerber or Wolfman do anything with it? I mean, it doesn't seem like a Marvel humor book, it seems like Sick under another title.

LEE: I don't know. I don't really know how to answer that…

ASKEGREN: People just lose interest?

LEE: I'm trying to remember. I don't remember what happened with Wolfman and Gerber on the book. I think I didn't feel the book was that important at the time and we had other comics we wanted them to do, and I decided I didn't want any of our regular comic writers doing it. So I got ahold of Paul Laikin, who was not one of our regular writers, and we gave Paul a lot of support. He spends full time on it, and it's been coming along. It's been building up sales over the months.

ASKEGREN: Marvel can't seem to get the black and whites distributed very well…

LEE. No… no.

ASKEGREN: You're still leagues ahead of Warren's distribution. Who distributes your material —Curtis?

LEE: Curtis. They're a good distributor. The problem is the dealers don't know where the hell to put those books. They really don't know. They can't keep them with the comics, they're too big and they don't fit. They're not going to put near Playboy, they're not gonna put it near the Reader's Digest, they really don't know where to put 'em. Some dealers get 'em and just ship 'em right back, they don't even put 'em on display. They feel, “Aaah, it's not worth it.”

ASKEGREN: That's what happened to Atlas. I don't want to dig into personal problems, but was there any bad blood between you and Larry Lieber when he took over as editor of…?

LEE: Nah… he asked me if I would mind, I said be my guest.

ASKEGREN: Are you and Martin Goodman speaking anymore?

LEE: No.

ASKEGREN: It's reached that point?

LEE: Yeah.

ASKEGREN: I saw Jeff Rovin when they were first announcing the line, and I asked him if maybe the cover designs weren't a little bit derivative…

LEE: They were like dead copies. Derivative! [Laughter]

ASKEGREN: I didn't want to say “swipes.”

LEE: No, but I was friendly to Larry, there was no trouble there.

DAWSON: Do you have any comments whatsoever on Len Wein's departure from Marvel? He was writing all your major books and…

LEE: Yeah, I was surprised. I was shocked…

ASKEGREN: Are you and Jenette Kahn still speaking? [Laughter]

LEE: Yeah, yeah… I just don't feel it's right for people who are our better artists or writers to be working for a competitive company. Maybe I'm old-fashioned, but I feel you should have loyalty to one company.

ASKEGREN: Have you ever considered a contract program like DC's done?

LEE: I don't want to get into those subjects. I think that's business. I don't think it's important for the fans to know.