Some of the very best and most popular contemporary “comics for adults” are memoirs of childhood and family tragedy. There are myriad examples, including blockbusters like Maus, Persepolis, and Fun Home. In each, there is real trauma going back at least a generation.

The Vagabond Valise, just out from Conundrum Press, is a new entrant for admission into the canon of very sad nonfiction graphic novels. It follows Chick-o, a stand-in for Canadian author Siris, through a long, disparate series of grievances and injustices in and out of the foster system in 1960s and ‘70s Quebec. There’s no question that it is sad: gross food, emotional and physical abuse, losing an adolescent crush when her house burns down. There is some rough stuff. But even though the contents sufficiently sad, I’m not sure that’s enough to make Valise good.

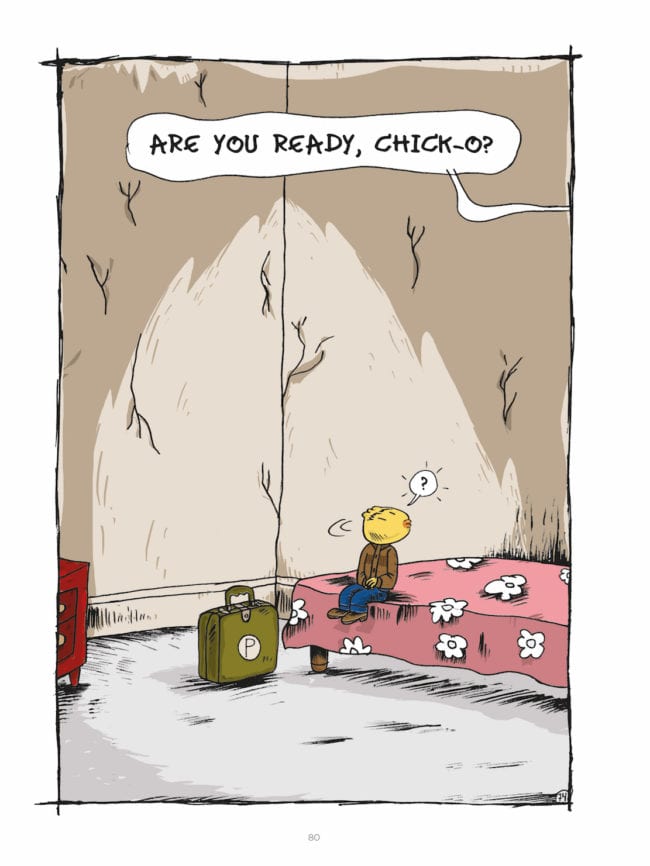

Siris has a scratchy line, likely from a nib pen, but it’s not super variable. There are few small details (forks on the dinner table are little tridents, backgrounds are sparse) and a loose hatching permeates nearly ever panel. This wobbliness can be endearing, and the art is on the more cartoony end of the spectrum, like Rocko’s Modern Life. There is a low-simmering magic realism a la Pee-wee’s Playhouse — Chick-o is a Lewis Trondheim-esque bird boy.

I don’t mind the playful style, even if it feels like a somewhat mismatched choice for the subject matter. This is Siris’ first book in English, but I gather he has a long history in French Canadian comics. If this is his style, developed over a career, then it only makes sense to the tell the story of his life this way.

There are some nice touches, like little flowers in word balloons meant to have flowery language. But there is too little variation in types of shot. Though there is movement, and action, far too much of it is depicted from the same, medium-sized vantage. Over the course of a three-hundred page graphic novel, I found myself longing for a bit of variety. And not every reader minds this, but occasionally Siris uses an arrow to show which panel to read next because his page layout doesn’t make it clear. More care could have been taken when arranging each page.

There are some nice touches, like little flowers in word balloons meant to have flowery language. But there is too little variation in types of shot. Though there is movement, and action, far too much of it is depicted from the same, medium-sized vantage. Over the course of a three-hundred page graphic novel, I found myself longing for a bit of variety. And not every reader minds this, but occasionally Siris uses an arrow to show which panel to read next because his page layout doesn’t make it clear. More care could have been taken when arranging each page.

Two parts of the book follow a conventional chronological structure. The book begins with Renzo, Chick-o’s/Siris’ father, suffering an injury which leads to his addiction to pills and beer. Mystifyingly, when Chick-o and his siblings are taken away from his parents, there is very little context for it. This change is the defining turn in the narrative on which the rest of the book hinges. And yet, when the book declares, “It was inevitable that, one day or another, the social workers would show up to take the kids away,” I was blindsided. After re-reading the preceding pages over and over I can see a pattern of Renzo losing jobs and the family having very little money. But the “inevitability” still seems to come from nowhere. Perhaps there is something missing in the translation from French.

The captions narrate the action as an omniscient narrator or presumably, an older and wiser Chick-o. But the narration in Valise has no emotional distance from any of the action. There’s scant insight or nuance toward the events unfolding. Even if the point is to condemn Quebec’s foster system, there are better ways to get there.

Siris seems to have been through some shit. If he truly reflects back on some of the adults in his childhood (father, nuns, foster parents, social workers) as evil, unredeemable people, that of course is his right. But I can’t root for that perspective as a reader. In the best graphic memoirs, the author interrogates her own feelings and probes her own memories from different perspectives. In Valise, Siris is more interested in exercising his demons than processing his trauma or reckoning with his past.

Siris seems to have been through some shit. If he truly reflects back on some of the adults in his childhood (father, nuns, foster parents, social workers) as evil, unredeemable people, that of course is his right. But I can’t root for that perspective as a reader. In the best graphic memoirs, the author interrogates her own feelings and probes her own memories from different perspectives. In Valise, Siris is more interested in exercising his demons than processing his trauma or reckoning with his past.

The last eighty pages or so, starting around Chick-o’s 15th birthday, show how life begins to get better. There are friends, although none of them truly get an identity or distinct personality, and eventually there is music and art and roller-skating. The glimpses into Montreal’s disco and punk scenes are interesting and fun, but like much of the book, barely scratch the surface of something that could be interesting.

In an epilogue, an older Chick-o opens his childhood valise and the ghostly memories of his foster family pop out to threaten him. He says to himself, “This time, I’m gonna do something!” In a move befitting his beloved Bugs Bunny, his vacuums them up, puts the bag back into the valise and tosses it into the river. The book ends on this strange metaphor. But for me, if Siris wants to lean on old cartooning tropes, I think his demons would be far better served by a vacuum with “Years of therapy” written on the side.