First published in 1960 and back in print again from the New York Review of Books, Saul Steinberg's The Labyrinth condenses the modern and the mythic into 250 pages of strange and wonderful cartoons. The fourth of Steinberg's seven major compilations, The Labyrinth covers his work between 1954 and 1960, loosely distilling the state of American mid-century cartooning. Quirky, obliquely intellectual, cosmopolitan, and deeply ironic, Steinberg's modernist approach addresses many of the major cultural changes in America during the 1950s. The Labyrinth touches on urbanization and suburbanization, the expansion of ready-made mass culture, the post-War shift in the relationship between men and women, the advent of televisual mass media, and the zany paranoia of the Cold War zeitgeist.

These themes find their (ever-shifting) forms in objects and figures culled from Steinberg's life in New York as well as his travels. We find ourselves in art museums and cocktail parties, playing baseball with the Milwaukee Braves and gazing on jockeys and their thoroughbred ponies. We find ourselves in motels and metropolises; we stroll down good ole American Main Street and get mashed into the masses of crowded Moscow. Steinberg gives us skyscrapers and lets us glimpse into their windows to peek at models, their sexy legs demurely-crossed. Maybe these ladies sit across from the artists at easels who populate The Labyrinth---the book is very much about ways of seeing the world. There are birds, there are cats; there are cubes, there are hats. We occasionally find ourselves in the mouths of monsters. It's a delicious affair.

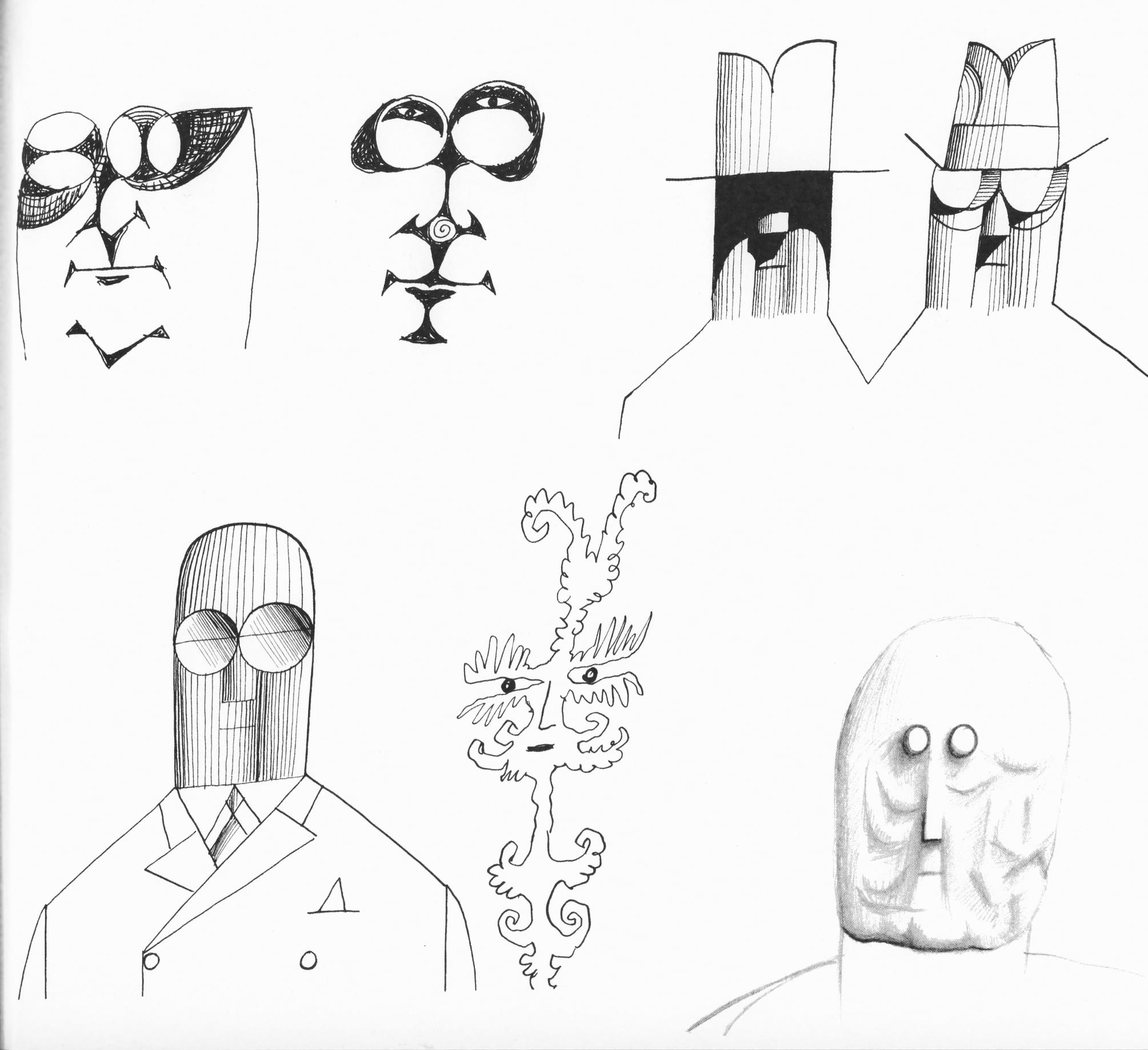

Steinberg's Labyrinth is a maze of aesthetic transfiguration. His illustrations show a full command of brush, nib, ink, and the various qualities of paper itself. Steinberg's lines course through the wordless novel, tangling the reader into cartoons and cubisms and caricatures, blemishes and brushstrokes, dots and loops that simultaneously satirize and substantiate mid-20th-century modernist art, when commercial illustrations and comics were transmuted into Pop Art. Under each seeming squiggle is an assured hand and an even sharper mind.

Steinberg emigrated to America in the early forties, escaping anti-Semitic fascist Romania. In New York City he gained recognition publishing in The New Yorker and other big magazines, titles that helped to reify a commercial national identity. The Labyrinth showcases an emigre's approach to not only understanding the American commercial mythos, but also adding to it, subverting it, and ultimately complicating and enriching it. Steinberg created his own inky-black demotic, a pulsing and wry language for his New World. Steinberg's invented vernacular is sometimes swirly, sometimes webby, sometimes straight-as-an-arrow; he pokes at the different columns that prop up Americana. Steinberg's lines read sometimes doric, sometimes ionic, sometimes Corinthian---but always Steinbergian.

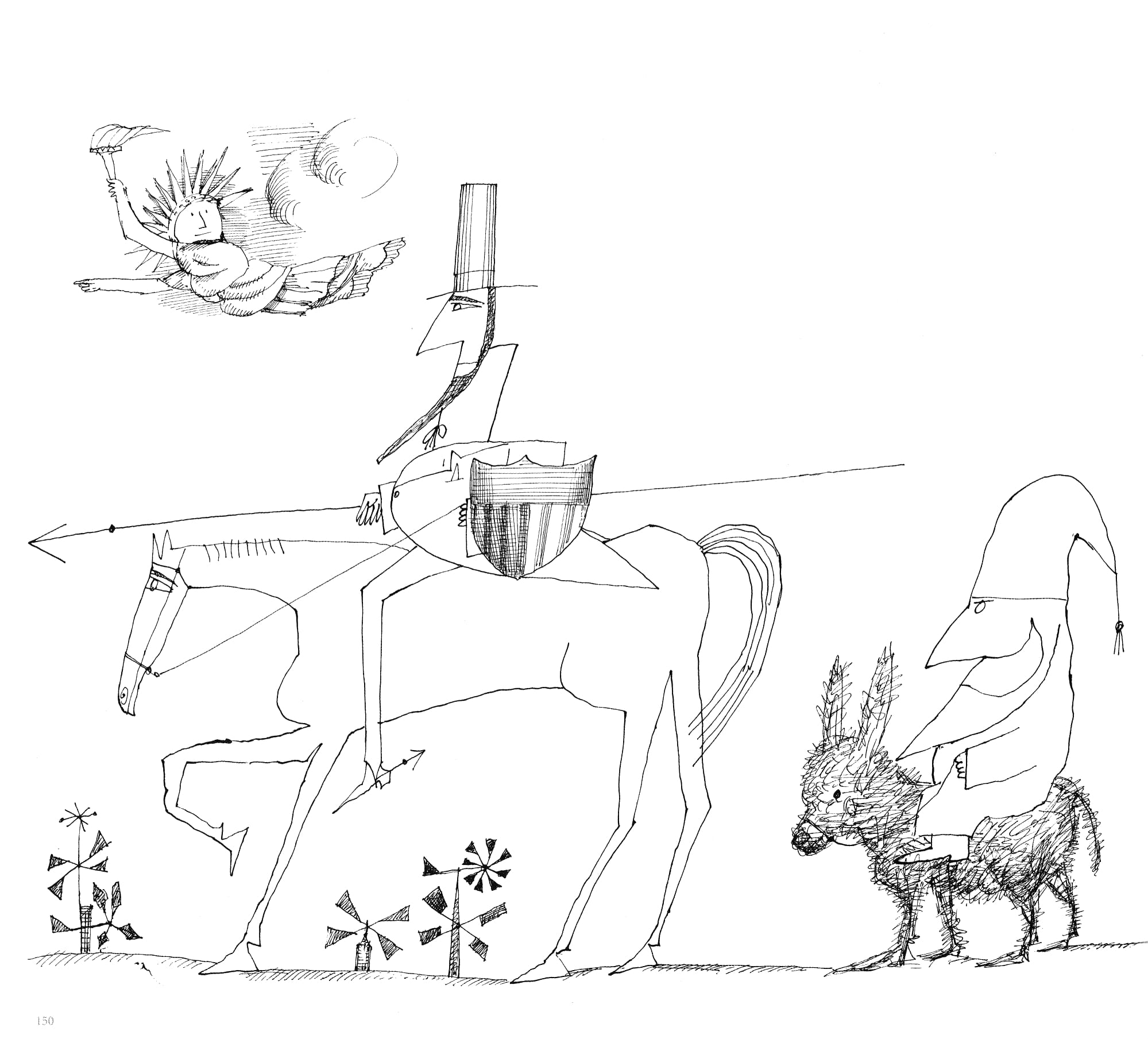

Steinberg's Labyrinth is a tangle of squiggles and dots, tangles and loops, the thread of which coheres into satirical scenes of well-dressed men and handsome heiresses, cityscapes and night scenes, cocktail parties and art shows. Steinberg enlarges America in his vision--it becomes a place of heroes and villains writ large. In one remarkable cartoon, Steinberg transfigures Abraham Lincoln into Don Quixote, and appends Santa Claus, bedonkeyed, in the role of Sancho Panza. The Statue of Liberty drifts ahead the ether, looking on approvingly. What better image to exemplify the American Fantasy?

Steinberg famously described himself as "a writer who draws." The Labyrinth shows us not just a writer or a drawer, but an artist forging a new language, one that might measure the oh-so-modern world of mid-century America. Steinberg could seemingly do anything with ink, and the range of inventions in The Labyrinth shows a keen engagement with the knotty chaotic chorus of American life. We get a new language here, but the newness may be hard to see, as so much of Steinberg's influence reverberates today in contemporary cartooning, comics, and advertising.

Steinberg's innovations are like those of the great American poet Walt Whitman, whose revolutionary style has been so muted and subsumed by commercial culture that it might be hard for us to fully appreciate the force and vitality of its art. Strong and strange art colonizes our language (which is to say our ways of seeing) from the past; we cannot sense its strangeness or fully appreciate its strength. The Labyrinth echoes Whitman's Leaves of Grass, which sought a century earlier to find a new language to describe a new country. Steinberg looked at America through new eyes and like Whitman before him found a new language of expression---the language of labyrinthine lines on paper, the artist before it, his orbs gazing not on his canvas---his hand writhe freely, black ink to white paper---but rather those orbs gaze on you, the audience, on America.