Frank King became America's master of quiet domestic drama on the daily comics page. His long-running Gasoline Alley told a sometimes melodramatic but generally gentle narrative in which his characters aged reasonably and passed through the phases of their lives. King's Sunday Gasoline Alley, in the 1920s and early '30s, before downsizing into a static half-page, showed an antic side of its creator. These much-celebrated episodes (the subject of one of Sunday Press' earlier giant-size books) made each page a playground—some wild, some mundane, but all with a sympathetic eye towards the characters and their daily lives.

The seeds of Frank King's cartooning, and its first full flower, are the subject of Sunday Press' latest extravaganza, Crazy Quilt: Scraps and Panels on the Way to Gasoline Alley.

Consumed by the ambition of becoming a graphic artist in his teens, King took a typical path of apprenticeships, art school studies, and stints at several Midwestern dailies before his arrival at the Chicago Tribune in 1909. King continued to learn on the job, with the encouragement of Robert McCormick and Joseph Patterson—the architects of the Tribune's graphics-enriched news pages and its stable of world-class cartoonists. As essayist Jeet Heer notes in one of the book's informative pieces, the paper's stance was conservative; its attitude towards graphics and comics was wide-open.

A few years before King's arrival, the Trib gave fine artist Lionel Feininger an elaborate four-color canvas for his expressionist comics fantasias The Kin-Der Kids and Wee Willie Winkie's World. Their roster of cartoonists and Sunday comic section would remain world-class well into the 1950s, and the high quality and subtlety of their journeyman European engravers gave the paper's printing a vibrance and elegance that stood alone.

Photographs of the young Frank King bring to mind the actor Jake Gyllenhaal, circa 2004. One can see a similar glint in King's eye, a brashness in his smile and an undisguised enjoyment of his life and work. King was at first in the shadow of the Tribune's master editorial cartoonist John T. McCutcheon. As one of the lower-status Trib cartoonists, King soldiered through spot illustrations for news stories, feature article illustrations and the occasional comic strip.

The globetrotting McCutcheon's frequent absences eventually gave King a crack at editorial cartooning. Among the early pieces reproduced in Crazy Quilt are an amusing pre-World War I series that depict a corpulent, inept Uncle Sam—clearly gone to seed and good company for Gene Ahern's yet-to-exist Major Amos Hoople.

In their essays, Heer, Chris Ware, and Warren Bernand rightfully point to the legendary spring 1913 Armory art show, which introduced Americans to cubism, fauvism, pointillism, and abstract art in its birth throes. It's worth noting that a few American newspaper cartoonists had works in this revolutionary exhibit; Heer gives the details in his essay.

King responded to this new art with excitement and passion, and its influence began to seep into his comics work. As a disciple of McCutcheon, King had, by the spring of 1913, mastered the old-school cross hatching and the standard look and feel of editorial cartooning. Now, he loosened up, and tell-tale signs of modernism entered, and would continue in his work for decades—distortion, exaggeration and freehand-drawn clear lines that allowed color to complete their sense of contour and perspective.

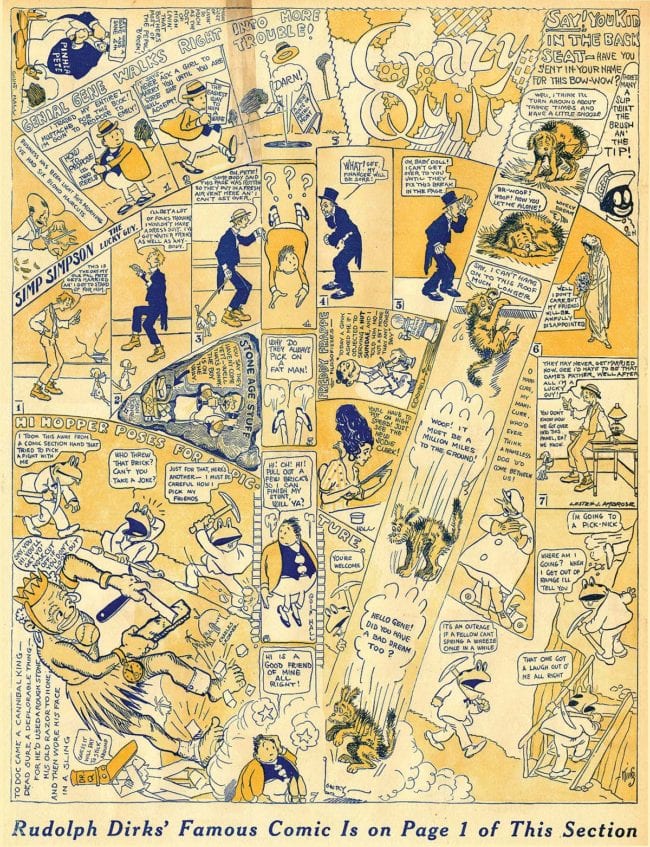

The Crazy Quilt strip is the obvious centerpiece of this handsome book—and the only full-color material of King's early career. The Tribune's then-slender Sunday comics section had full-color on its outer wrap. Inner comics had one ghastly hue of some neutral color, in various strengths. This continued well into the early run of King's signature strip, Gasoline Alley (the first Sunday page is included as an apt post-script at book's end).

Crazy Quilt is a jam comic—a single-page strip attended to by a group of cartoonists who typically react to and build upon what has come before, and what will soon be. Unlike most jams, which are linear, Crazy Quilt's group of cartoonists snake all over the page, in all directions—disrupting others' work, commenting upon it and otherwise unhinging the fourth wall with a delight that translates, 100+ years later, to the reader.

King is the clear superstar of Crazy Quilt, and his irascible Hi Hopper is the highlight of each page. Quin Hall's sprightly line and dry wit makes his “Genial Gene” and “Pinhead Pete” apt sparring partners for Hi Hopper, and their shared panels are the money shot of each Crazy Quilt. Duller, less engaged artists like Lester Ambrose and Everett Lowry remind us that there have always been lesser lights in the comics firmament, and the mix of inspiration and mediocrity becomes fascinating. Is there a less appealing comic strip than Ambrose's Simp Simpson?

Crazy Quilt ran from spring to summer 1914. Perhaps all parties involved felt the idea was played out; perhaps it was too out-there for its conservative Midwestern audience. It's surprising that no one else tried to emulate this winning formula on the newspaper comics pages. When the first wave of underground cartoonists jammed in Zap Comix, this refreshing and spontaneous concept again bore fruit.

The last Crazy Quilt page broke up the over-under-sideways-down format into isolated rows. King's Hi Hopper takes a moment to bitch about this constraint: “I'm in favor of unconventionality—these holes ought to be broken up more!” He kicks and blows smoke at the panel borders till they disintegrate. In a rabbit hole of a gnarled panel, Hopper states: “Gosh! If I had to live in a square I'd croak!”

The Crazy Quilt experience had King all fired up, and he continued to play with different comic strip ideas. This attitude was at work before the jam strip. His manic, anarchic Motorcycle Mike preceded Quilt, and its smash-and-burn protagonist is a modernist figure. Affixed to his noisy, destructive gas-powered vehicle, seemingly in perpetual motion, Mike obliterates everything he encounters. The gag soon gets thin, but the brutal energy of his chaos and mayhem are a signal of the end of the Victorian era in American society.

A liberal sampling of King's other early strips include some Rube Goldberg-esque social observation humor and some elegant pieces the artist did for Cartoons magazine, including the sublime “How to be a Comic Artist in One Lesson.” Some of King's early strips, including Jonah, a Whale for Trouble, are limited by a thin theme, but offer antic, limb-flaying cartooning with great eye appeal.

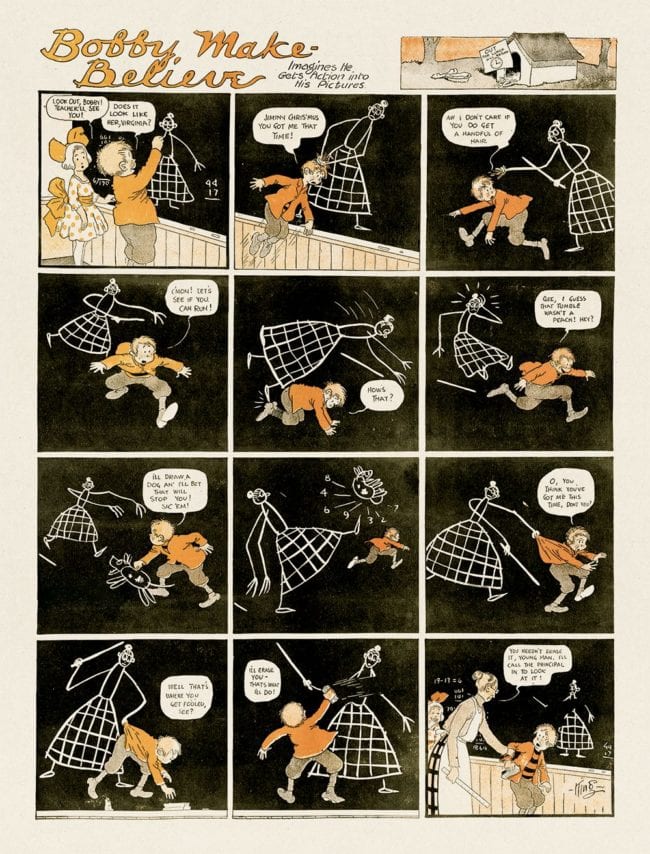

King's longest-lived Sunday strip, pre-Gasoline Alley, was Bobby Make-Believe, which ran in two colors inside the Trib comics section for a few years. Often decried as a rip-off of Winsor McCay's Little Nemo in Slumberland, Bobby offers a different take on the daydream vs. reality concept. Bobby is a more active participant in his fantasias, which typically build upon the introduction of one exotic element into the kiddo's humdrum Midwestern life.

With its foreshadowing of elements that made the Sunday Gasoline Alley of the later 1920s and early 1930s such a treat, King evokes considerable impact from his limited hues, which he often mixes with mechanical greys to achieve a wider palette. The spacious contours and expressive body language of Alley are in evidence.

Two outstanding Bobby Make-Believe strips from 1917 play with the tools of cartooning—the drawn line and hand-lettered typography—with a transcendence that still seems fresh 100 years after their first publication. If these two strips don't make you champ at the bit to acquire Crazy Quilt, check your pulse for signs of life.

Though Gasoline Alley, in its daily episodes, became a quiet, subtle account of day-to-day life—with occasional inroads to melodrama—Frank King never lost his appreciation for comics' invitation to come out and play. Consider this May 12, 1948 daily, which throws a formal coup at the reader while engaging them in the ongoing narrative:

Knowing that such notions still crossed King's mind this late in his career, three decades into Gasoline Alley, reminds us of that rascally young cartoonist and his infectious smile. Some of that younger self still inhabited King's artistry and world-view. As Crazy Quilt reminds us, the pull of the avant-garde had a powerful effect on the development of the American comic strip. Frank King's ability to incorporate it into a comic strip built on determined mundanity—remains one of the miracles of American cartooning. As Sunday Press keeps reminding us, we have a lot to learn from century-old comics and their creators.