In Wonder Woman: Earth One Vol. 2 Grant Morrison and Yanick Paquette come as close as anyone ever has to turning feminist psychologist and jovial crank William Marston's original feminist fantasy for kids into a modern adventure story for adults. That's an impressive achievement, and the resulting comic is perhaps truer to the original's odd genius than any creator has managed in decades. But Earth One also shows how important the childishness was to the original Wonder Woman. Adults have their uses, but kids, it turns out, are better at utopia.

Usually when people discuss "adult content", they mean sex. But the original Wonder Woman comics by were saturated with themes of lesbianism, bondage,and cheerful eroticism intended to thrill and entertain children of all ages. Marston, who in his personal life lived in a polyamorous relationsip with two bisexual women, believed that loving submission to eroticized female authority led adults and children of every gender to peace, happiness, and matriarchal utopia.

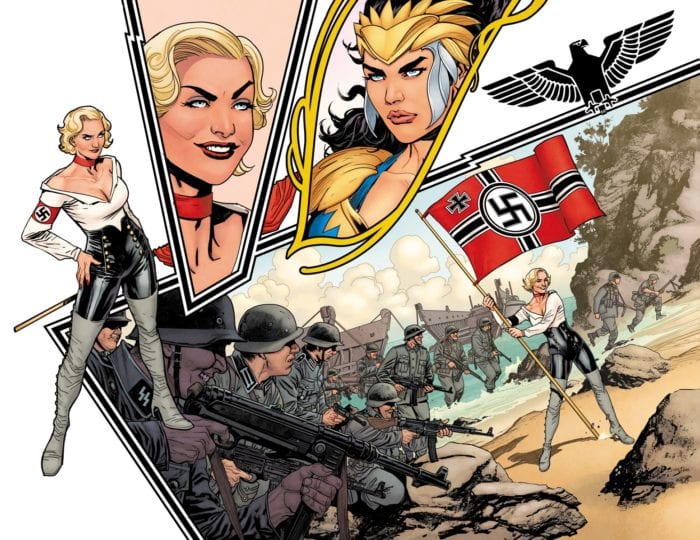

Morrison and Paquette aren't quite true believers, but they obviously enjoy pretending. Volume 2 kicks off with Nazi superwoman (and Marston creation) Paula Von Gunther invading Paradise Island with a battalion of storm troopers during World War II. She's quickly subdued (in various senses) by Queen Hippolyta and her warriors, who fire orgone blasts that convert Nazi soldiers to love as each cries out with an ecstatic "yes!" Paula herself realizes that she should submit to the love of women, rather than to the hate of man, and falls in infatuation in quick succession with Hippolyta and with Diana, aka Wonder Woman. Paquette's drawing of Paula's moment of transformation— eyes wide, expression rapturous—would please Marston mightily. That's exactly how he wanted his readers, girls and boys, to look at Wonder Woman—as a love leader who will restrain us, retrain us and lead us all to kink and virtue.

With Paula under control, the narrative then jumps to the present, when Wonder Woman has come to man's world to try to teach the modern era the lessons of love and peace. There Diana faces off with Dr. Psycho, a psychic rapist and one of Marston's nastiest villains. Morrison rewrites Psycho as a PUA (pick-up artist) misogynist scumbag, who pretends to be a sensitive new age guy in order to seduce and hypnotize Diana. He gets her to make warlike public pronouncements in order to justify an assault on Paradise Island. Diana is, in true Marston-fashion, saved by female friendship. In the recent Wonder Woman film, Diana is surrounded by a team of guys, but not so here. The unapologetically fat Holliday college student Etta Candy and her pals, along with Diana's Amazon sisters, race to Diana's rescue, helping her move from sub (under Psycho) to her rightful place, as dom.

With Paula under control, the narrative then jumps to the present, when Wonder Woman has come to man's world to try to teach the modern era the lessons of love and peace. There Diana faces off with Dr. Psycho, a psychic rapist and one of Marston's nastiest villains. Morrison rewrites Psycho as a PUA (pick-up artist) misogynist scumbag, who pretends to be a sensitive new age guy in order to seduce and hypnotize Diana. He gets her to make warlike public pronouncements in order to justify an assault on Paradise Island. Diana is, in true Marston-fashion, saved by female friendship. In the recent Wonder Woman film, Diana is surrounded by a team of guys, but not so here. The unapologetically fat Holliday college student Etta Candy and her pals, along with Diana's Amazon sisters, race to Diana's rescue, helping her move from sub (under Psycho) to her rightful place, as dom.

Morrison, then, loyally repurporses and restates Marston's themes of feminism, sex, bondage, and female friendship. Where he diverges is by adding tragedy—and specifically the tragedy of growing up.

Diana in Volume 2 has left Paradise Island, which means that she can no longer drink the waters of youth. She starts to learn about sadness, grief, and regret. Traveling to man's world means becoming an adult, and leaving childish things behind. That's a kind of Oedipal drama. To become an adult and a queen, Diana has to depart the womb and separate herself from the mother. Then the king (or in this case the queen) has to die so that Diana can take her place. Adulthood is abandoning your parents, and cutting off your connection to them, in order to find your own way.

Marston, though, explicitly rejected this Freudian narrative. His treatise, Emotions of Normal People, was written as a rebuke to Freud's psychological theories, which presented mother love, kink, and desire as perverse. For Marston, it was normal and healthy and awesome to love your mother. Happy adulthood for Marston meant submitting to matriarchy forever. You don't need to escape mom to do your own thing and be an autonomous person; autonomy isn't so great in Marston's vision anyway. Being a whole, functional adult doesn't mean breaking family bonds. It means submitting to mom's loving authority.

In Marston's comics, Wonder Woman doesn't have to sever herself from immortality and Paradise Island in order to go to man's world; she comes back and visits her mom all the time. And when she gets in trouble or finds herself in over her head, her mom bails her out, not by sacrificing herself, but by racing to the rescue. In Marston, the one person more powerful than Wonder Woman is Wonder Woman's mom, because mothers are awesome and take care of everything.

In Marston's comics, Wonder Woman doesn't have to sever herself from immortality and Paradise Island in order to go to man's world; she comes back and visits her mom all the time. And when she gets in trouble or finds herself in over her head, her mom bails her out, not by sacrificing herself, but by racing to the rescue. In Marston, the one person more powerful than Wonder Woman is Wonder Woman's mom, because mothers are awesome and take care of everything.

Freud—and much of adventure fiction—sees separation from home and mother as vital to growth. Paquette stuffs his pages full of panels with odd shaped, curling borders. It suggests feminine curves and flexible structures—but it also feels like the images are trying to break free of their bonds, to grow and flourish and take on new shapes. The original Wonder Woman artist, Harry Peter, didn't convey that kind of anxiety. Instead, his images were frozen in stiff poses, with tactile, flowing, animated lines, so each image looked like an energized, frilly, joyous tableau. Rather than trying to spill out of constraints, Peter's drawings find pleasure and freedom in constriction—or, if you will, in loving authority.

In turning Wonder Woman into a story about growing up for adults, then, Morrison both betrays the Marston originals, and robs them of some of their sophistication and thematic coherence. Paradise Island is a place where polymorphous sexuality abounds without guilt because it's a place where mother always rules. It's an unchanging utopia of forgiveness and love because it's a matriarchy. Morrison wants to be true to that vision, but he can't help but kill his father. Those myths of adult freedom trap just about every man.