The story of Al Capp and Ham Fisher, two cartooning geniuses, their rise to celebrity and their furious interactions with each other, is the stuff of epic adventure fiction, but here, it is fact.

At the peak of their careers, in the 1950s, they were superstars: Capp reached 90 million readers and earned $500,000 a year ($4 million in today’s dollars); Fisher, 100 million readers and $550,000 (over $4.5 million in today’s dollars).

Their creations were in movies and on stage.

Shamed by his colleagues at the height of his career, Fisher died by his own hand; Capp died in obscurity, disgraced by sensational news of his sexual scandals.

HE WASN’T LIMPING; HE WAS LURCHING. He swung his left leg out sideways, almost dragging it forward for each step, and his stride had a practiced rhythm, a rolling gait punctuated by a profound dip every time he transferred his weight to his left leg, the wooden one. But it wasn’t the lurch that attracted the attention of the man in the limousine so much as it was the sheaf of paper in a blue wrapper that the tottering stroller had tucked under his arm. The man in the limousine was a cartoonist, and he thought he recognized the blue wrapping paper: it was, he believed, the paper his syndicate used to wrap rejected artwork in when returning it to hapless supplicants.

“Pull up alongside that fellow,” the man said to his chauffeur. And he turned to the woman seated next to him, and said, “I bet that guy is a cartoonist.”

The subject of this wager, the young man rolling along the sidewalk on Eighth Avenue near Columbus Circle, was a somewhat shabby specimen, who, despite the chill of the spring day, was hatless and nearly coatless. But he didn’t need a hat. He had a shaggy mop of thick, black hair. He had been in New York only a few weeks, and the six dollars he’d arrived with had long since evaporated. If it hadn’t been for the kindness of his landlady, whose boundless faith in her tenant’s artistic skill prompted her to stake him to his assault on the citadels of the mass media, he would have been back in his native Boston. She let him stay in her attic without paying and even gave him a little money every day for food.

He noticed the limousine slowing down as it pulled alongside him, and he watched as the rear window rolled down, and he saw the man in the back, seated next to a well-dressed woman. The man looked at him and said:

“I’ve bet my sister that you’re a cartoonist. Are you?”

He was. Or, rather, that’s what Alfred G. Caplin aspired to be that spring of 1933. And he had even sold a few cartoons from time to time, both in New York and in Boston. The year before, he had been in New York drawing a syndicated cartoon feature about a pompous young blowhard, but his heart hadn’t been in it, so he gave it up and returned to Boston and his new wife. And now, six months later, he was back in the Big Apple for another try at fame and fortune. It wasn’t a good time to be looking. The nation was firmly in the grip of what would later be called “the Great Depression.” Nationwide, 14 million were out of work. In New York, 82 breadlines filled a million jobless bellies, but 29 New Yorkers would die of starvation that year. So when the man in the limousine offered him $10 to do some drawing for him, Caplin took him up on it.

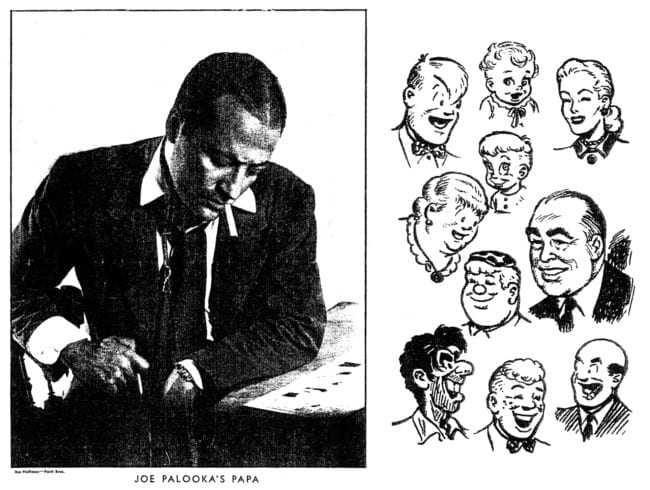

And that’s how Al Capp, as he would later sign himself, met Ham Fisher, who, in the spring of 1933, was the famed creator of Joe Palooka, a comic strip about a somewhat simpleminded prize fighter who had, by accident, become the heavyweight champion of the world. It was a fateful encounter, as fraught with impending event as anything in the cliffhanging comic strips of the day’s newspapers. Capp earned his 10 bucks by finishing a Sunday Palooka, and he performed well enough that Fisher hired him as his assistant at $22.50 a week. Or thereabouts. Capp did the Sunday strips, and within a few months, he was writing as well as drawing them. But before the year was out, he would leave Fisher to devote his energies to creating his own comic strip, and in the summer of 1934, he too became a syndicated cartoonist with the debut of Li’l Abner. He would become as famous and fêted as Fisher.

Two giants in their field, and yet when they came together, each was brought low, undone, by the same lie. And then each would destroy himself. And in their self-destruction, they would share a star-crossed fate as surely as if joined at the hip that day they met on Eighth Avenue near Columbus Circle.

I. Fisher vs Capp

HAM FISHER IS THE MOST CELEBRATED CARTOONIST ever to have been drummed out of the National Cartoonists Society. He may not be the only cartoonist to be so defrocked. But his is surely the most famous case in the annals of the Society. His exit was noisy. For a brief while. And then, all fell silent.

Fisher was dead. He committed suicide within a year of the disgrace of his banishment. His name hasn’t been mentioned much since. And the silence is only one of the strange elements in this ignoble episode.

It was the notorious feud between Fisher and Capp that precipitated events resulting in Fisher’s ouster from the ranks of the Society. The story of the feud is juicy with the sort of morbid sensation that enlivens supermarket tabloids: vicarious sex, scandalous accusation, denials and attempted cover-ups, high dudgeon and low humor, and disgrace and death. But there is high drama in the tale, too, in the impulse to self-destruction. And there are also contradictory aspects in the traditional rehearsal of the story, puzzles never quite solved. So it seemed to me a story worth exhumation, one of those legends that begs for careful inspection.

I didn’t always hold this conviction. But several years ago, sometime in the 1990s, I met cartoonist Morris Weiss, and over dinner with Weiss and his wife Blanche at a little place near his home in Florida, he started talking about the various places the path of his career had crossed the path of Ham Fisher’s. Weiss speaks with an admirable precision, clipping his words into a lilting syntax as he goes. No, he said in answer to my question, he didn’t think of himself as a particular friend of Fisher’s. Fisher was not a nice man, he said. Not the sort of man you’d be the friend of. But Fisher hadn’t been treated fairly, Weiss said.

My curiosity piqued, I decided to look into the sordid tale of the feud between Fisher and Capp. And when I did, I found in the contradictions truths that, it seemed to me, had long been overlooked.

Morris Weiss’ connection with Fisher, an admittedly tangential one, began early and ran late. Weiss spent most of his cartooning career with one or the other of two newspaper comic strips, Mickey Finn and Joe Palooka. Joe Palooka was Ham Fisher’s creation, but Weiss didn’t work on the strip with Fisher. By the time Weiss arrived at the strip, Fisher had been dead for years.

At the age of 19, Weiss entered the profession by lettering Ed Wheelan’s Minute Movies. After similar stints with Pedro Llanuza on Joe Jinks and with Harold Knerr on The Katzenjammer Kids, Weiss began assisting Lank Leonard in 1936 just as the latter launched Mickey Finn, a strip about a kindly young workaday policeman and his Irish family. Following service in the Army in World War II, Weiss resumed his career by doing comic books for Stan Lee at Timely. Then in 1960, Weiss rejoined Leonard, eventually taking over Mickey Finn in 1968 and continuing the strip until it ceased in 1977. For about the same period, he also wrote Joe Palooka, which was then being drawn by Tony DiPreta, who would draw the strip until it ended Nov. 4, 1984.

While still a teenager attending the High School of Commerce in New York City, Weiss visited many cartoonists in their studios, seeking advice about how to enter the profession. Among those he visited was Ham Fisher. It was about 1932 or 1933, very early in the run of Joe Palooka, and Fisher had an apartment in the Parc Vendome, a posh apartment building in Manhattan.

“Ham had moved into the Parc Vendome to live in the same building with James Montgomery Flagg,” Weiss told me. “Ham was very much conscious of celebrities; he wanted to meet the celebrities and mingle with them. So, he befriended Flagg and moved into the same apartment house as he lived in. Ham was very nice when I saw him back then. He gave me a drawing. And then I didn’t see him until many years later.”

The next time Weiss encountered Fisher was in 1944, when Weiss was in the Army and home in New York on furlough. “I dropped in at the McNaught Syndicate [which distributed Mickey Finn as well as Joe Palooka] for some reason or other, and Ham was there, and we left together and shared a cab to where he was going. I recall he was telling the cabbie stories of the things he was doing for the soldiers through the comic strip and with chalk talks in hospitals and things like that. And when the cabbie heard everything Ham had to say — apparently the cabbie was already a veteran, and he started to tell Ham stories about his Army life, and at that point, Ham lost interest.”

Clearly, Weiss implied, Fisher was too wrapped up in himself to listen to anyone else’s life story. At this time in his career, Fisher was a national celebrity of “Roman self-esteem,” as Time put it (Nov. 6, 1950), and around New York City, he was a well-known denizen of fashionable nightlife. “He lived like a lord,” writes Jay Maeder in “Fisher’s End,” published in Hogan’s Alley #8 (Fall 2000), “and he always had the best seats at the races and the prizefights and the musicals, and he played golf with Bing Crosby and boasted about it.”

Fisher was widely known and liked in the sporting world. He watched every notable prize fight from the press box, and the fans were reportedly as eager to see him as they were to see the fight. He was welcome in every training camp and fight gym. He was a member of the Boxing Writers Association, and he spent much of his time outside his studio at training camps, “picking up ring color and even sparring with the fighters,” reported Newsweek (Dec. 12, 1939).

Joe Palooka was without question one of the most popular comic strips of the period. Depicting the adventures of a good-hearted if somewhat simple-minded prize fighter (ostensibly, the world’s heavyweight champion), the strip consistently placed among the top five comic strips in readership surveys in the ’40s and early ’50s. According to a 1950 report in Time, Fisher’s strip was right up there with Blondie, Little Orphan Annie, Dick Tracy and Li’l Abner.

Fisher told action-oriented adventure stories, full of exotic incident as well as a healthy dose of humor. And he was expert at prolonging the agonies he inflicted upon his characters, creating suspense-filled storylines the equal of any contrived by his cohorts in the cliffhanger game. His cast included Joe’s long-suffering and voluble manager, Knobby Walsh, who loves Joe but has an eye always on gate receipts, too. Reportedly a blend of the personalities of several prominent fight personalities, notably Jack Bulger (once handler of Mickey Walker) and Doc Kearns (Jack Dempsey’s manager) and Tom Quigley (a Wilkes-Barre boxing promoter), Knobby is often supposed to be Fisher’s alter ego in the strip, a supposition Fisher himself fostered. The other principal character is Joe’s fiancé, the beauteous blonde Ann Howe, whom the champ finally marries on June 24, 1949, after an 18-year engagement. (It was in the air. Dick Tracy married Tess Trueheart on Christmas Eve, 1949; and Li’l Abner married Daisy Mae on March 29, 1952.) To this group, Fisher added redheaded Jerry Leemy, Joe’s excitable wartime Army buddy, and, later, the hugely comic heavyweight, Humphrey Pennyworth, a 300-pound village blacksmith with a heart of gold who is probably the only person we are certain could defeat Palooka in the ring, and, later still, the homeless waif Max, a diminutive monument to unadulterated (which is to say cloying) sweetness, always attired in cast-off shoes too large for him and wearing an out-sized hat. The inspiration for Max, according to William C. Kashatus in Pennsylvania Heritage (Spring 2000), was Max Bartikowsky, a kid who lived in Fisher’s old Wilkes-Barre neighborhood who would sometimes dress up in his mother’s floppy hats and his father’s big shoes and go running up and down the street. Said Bartikowsky: “I guess that left an impression with Fisher.”

As for Joe himself, it isn’t quite accurate to say he is simple-minded. But how else do you describe such an uncomplicated character?

To begin with, he’s big and strong. He is, after all, a professional boxer. His shoulders are broader than anyone else’s in the strip. Except those of his opponents in the ring. He’s also entirely, doggedly, wholesome. He’s thoughtful, compassionate and completely loyal. And humble, relentlessly humble. He embodies clean living, clean talking and clean thinking, not to mention honesty, courage, tolerance and devotion to duty, country, mother and apple pie. You see what I mean by “uncomplicated?"

Even his face is uncomplicated: It’s absolutely plain, completely open and unassuming. Manly lantern jaw, tiny nose, gigantic shock of forelock, wide-open eyes. It’s the sort of face you expect on a man incapable of dissembling. Or of compromise. Or of anything mean, small, or even remotely unkind. With Joe Palooka, what you see is what you get. Simply stated, he is an ideal. An American ideal of manhood. Or of knighthood, for that is what he is: a kindly, gracious knight, righter of wrongs, defender of truth, beauty, justice and the American way.

While the artwork in Palooka is distinctive and well done, it isn’t of the caliber of Alex Raymond or Hal Foster or Milton Caniff in Flash Gordon, Prince Valiant or Terry and the Pirates. It’s the stories rather than the artwork that grip and hold the reader of Fisher’s strip. There are, for example, plenty of boxing matches, and Fisher made engrossing stories out of them. Fisher’s sequences in the boxing ring are enthralling to witness. They are skillfully and realistically choreographed, every move carefully plotted. And every move that is depicted is given significance in the story, too; no wasted motions here. Every picture is accompanied by a “voice-over” narrative — the voice of a radio announcer describing to his audience what he sees. In those golden days of yesteryear before television, we “watched” such athletic contests as boxing matches through the eyes of a radio announcer. So Fisher’s device enhanced the illusion of reality in the strip.

Fisher’s homely locutions, the merciless contractions that infest his hero’s utterances, suggest a soft-spoken manner of address. And that, in turn, reflects Joe’s essential humility, his “just folks” origins, his redeeming lack of sophistication, his wholly unpretentious personality. There’s nothing “elegunt” (as Fisher would have him say) about his speech. He says things like: “Kin ya ’magine?” “Honist.” “I been insalted.” “I wish I could go somewheres and jist be fergot.” And when he’s excited, “Tch, tch” — his most fervent expletive. And, always a model of good manners, “Than-kyou.”

Throughout his run on the strip, Fisher reflected the beliefs of his audience. Joe Palooka was, above all else, a sentimental strip. But it was unabashed, traditional American sentiment, born and bred in the custom and aspiration of the American spirit. Its raw sentimentality may undermine our interest these days; but during the years of World War II — and for a period both before and after — the strip was in perfect step with the times. Coulton Waugh, whose venerable 1947 work The Comics successfully shaped comics criticism for decades, says this about Fisher’s strip:

The great quality that lifts the strip to the very top is simply the heart in it, the human love. All people ... know that it is love that makes men rank above the brutes, but it is exceedingly difficult to write about or speak of this precious business without assuming the righteous attitude, the smallest hint of which sends the public scampering. ... In this respect, Ham Fisher resembles Milton Caniff: Neither spoils his work with preachiness.

Things just happen in the life of Joe Palooka; he doesn’t go out of his way to be good, it’s just in him. He reacts with greatness because he can’t help it. ... Simple people [took] as an ideal the big, graceful guy with thunder in his fist and with humility in his heart. ... He was one of them.

Year after year, Fisher told a riveting story. And his stories gave his readers something to admire, to emulate. And so why don’t we hear more about Ham Fisher and Joe Palooka in these days of revived interest in the cultural artifacts of newspaper comic strips in their Golden Age?

True, the strip’s often cloying mawkishness makes it a little less than congenial reading nowadays. But there’s more to it than that. There’s also Ham Fisher himself. And to understand the near disappearance of Joe Palooka from the pantheon of comic-strip greats, we have to know something more about Ham Fisher.

Next: Ham and Joe