Against our better judgment and the will of this world, we have returned with another wild ride through the best comics of 2022. Earnestly, passionately, we thank these dozens of volunteers for their viewpoints on the topic. The narrative formats below will differ, and opinions will contradict: we urge you, sweet reader, to indulge this post as a cartographic tour, in a less-than-straight line.

-The Editors

* * *

Cast of Characters

(click for fast travel)

Jean Marc Ah-Sen

Ben Austin-Docampo

Ritesh Babu

Derik Badman

Jason Bergman

Clark Burscough

RJ Casey

Henry Chamberlain

Helen Chazan

Austin English

Andrew Farago

Gina Gagliano

Matteo Gaspari

Charles Hatfield

Tim Hayes

John Kelly

Sally Madden

Mardou

Chris Mautner

Joe McCulloch

Brian Nicholson

Joe Ollmann

Zach Rabiroff

Oliver Ristau

Cynthia Rose

Matt Seneca

Tom Shapira

Katie Skelly

Valerio Stivè

Aug Stone

Tucker Stone

Floyd Tangeman

Marc Tessier

* * *

Jean Marc Ah-Sen

My favorite comic releases and reissues of the year, in no particular order:

Vuzz - Philippe Druillet, translated by Christopher Pope (Titan Comics)

The Silver Coin - Michael Walsh & various (Image Comics)

Defenders - Al Ewing & Javier Rodríguez, with Álvaro López & VC's Joe Caramagna (Marvel Comics)

Damn Them All - Si Spurrier, Charlie Adlard & Sofie Dodgson, with Shayne Hannah Cui & Jim Campbell (BOOM! Studios)

Lance Stanton - Wayward Warrior - James MacNaughton III & Dave Bamford (Floating World Comics)

Supergirl: Woman of Tomorrow - Tom King, Bilquis Evely, Matheus Lopes & Clayton Cowles (DC Comics)

Sir Alfred No. 3 - Tim Hensley (Fantagraphics)

Iron Man - Christopher Cantwell, Angel Unzueta & various (Marvel Comics)

Old Dog - Declan Shalvey, with Clayton Cowles (Image Comics)

A Righteous Thirst for Vengeance - Rick Remender & André Lima Araújo, with Chris O'Halloran & Rus Wooton (Image Comics)

Faithless III - Brian Azzarello & Maria Llovet, with AndWorld Design (BOOM! Studios)

Two Moons - John Arcudi & Valerio Giangiordano, with Bill Crabtree, Giovanna Niro, Jeromy Cox & Michael Heisler (Image Comics)

Talk to My Back - Yamada Murasaki, translated by Ryan Holmberg (Drawn & Quarterly)

Schappi - Anna Haifisch (Fantagraphics)

The Nice House on the Lake - James Tynion IV, Álvaro Martínez Bueno & Jordie Bellaire, with AndWorld Design (DC Comics)

Prison Pit: The Complete Collection - Johnny Ryan (Fantagraphics)

Disciples - David Birke, Nicholas McCarthy & Benjamin Marra (Fantagraphics)

* * *

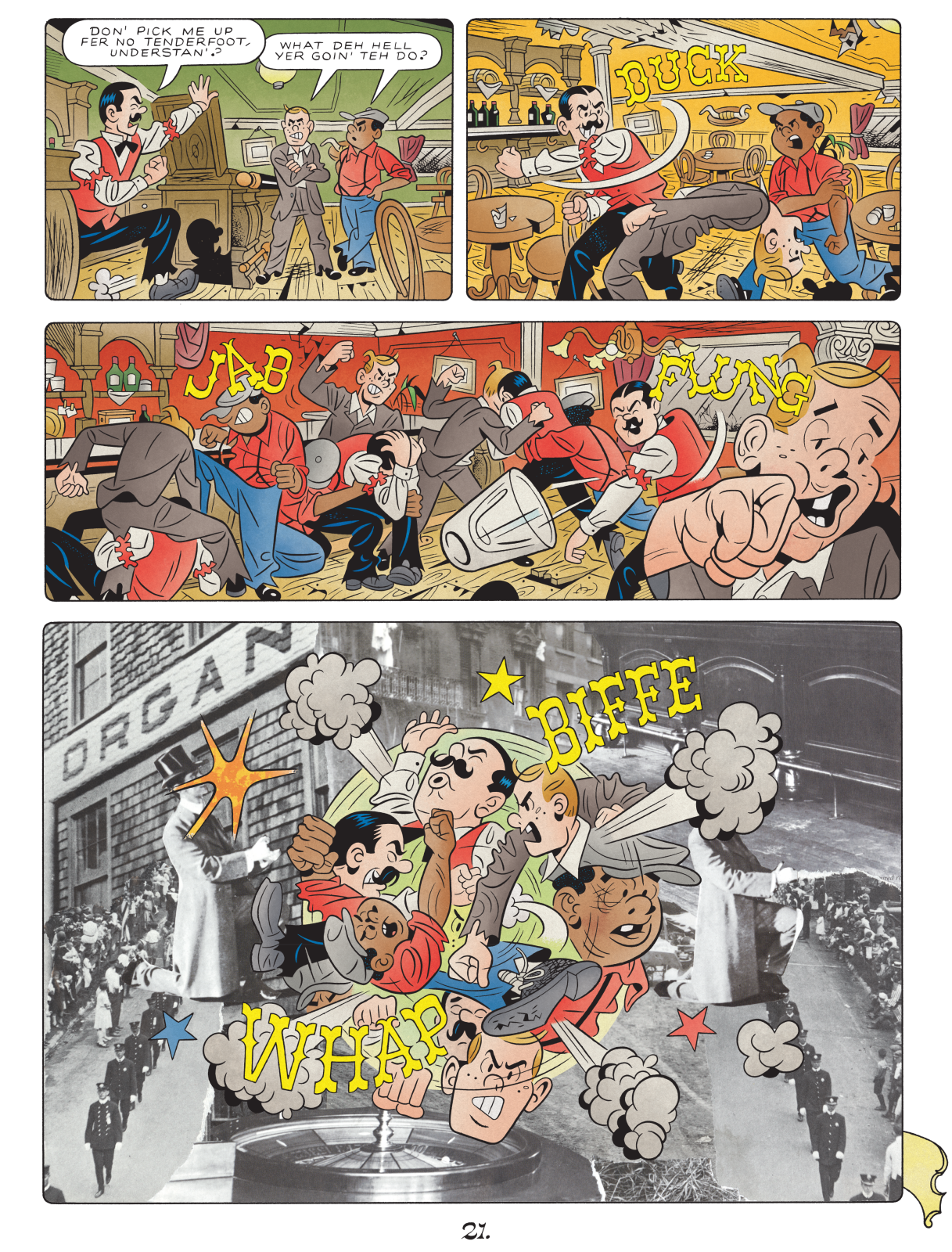

Ben Austin-Docampo

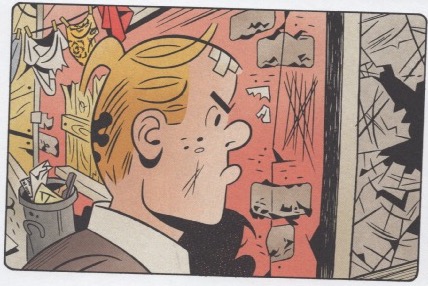

Wowwee Zowwee and Holy Hell! These are the kinds of well-articulated thoughts that zip through my mind when I’m holding Blood of the Virgin: Crickets Colour Special Number One by the one and only Sammy Harkham. Herein contained are page after page of cartooning at the highest level. I mean, damn. More learned comics scholars can tell you better than I which early 20th century cartoonists are being referenced, what styles are being invoked, and so on... suffice it to say that Harkham is a cartoonist’s cartoonist. His incredible skill and love of the medium fairly drips from the panels.

This handsome 11" x 14" edition features new covers and artwork, as well as remastered coloring of a story first published in Kramers Ergot 10 from Fantagraphics. I hesitate to even give scant details of the story here, simply because whatever I write will fall short of the actual object and may prejudice some readers away from picking it up for fear that it isn’t their thing. Well, let me do what I can to disabuse you of that notion here and now. If you love comics, Blood of the Virgin is for you.

Dare to read about a young cowboy named Joe who gets into the moviemaking biz near its inception and stays with it as the decades pass and the industry changes and evolves. Experience the widening triumphs and bitter disappointments that shape Joe into a jagged edge. Luxuriate in the scenic Western idyll both rural and urban. Lap up the early Hollywood nonchalance and quiet studies of Los Angeles Harkham excels at here as he does throughout Crickets. All this and a bumper sticker can be yours for the low, low price of $14.00 available from The Secret Headquarters, which published this item in collaboration with Commonwealth Comics Co. Don’t hesitate, buy your copy and support one of the best working cartoonists and independent comic book stores in existence today. Not to be missed.

* * *

Ritesh Babu

Comics this year had a great deal to talk about and think about. From the arrival of Kate Beaton's tome on the Canadian oil sands to the English publication of Hitoshi Ashinano's joyous sci-fi classic, there was a great deal to like and enjoy. Jonathan Case came in strong this year, delivering one of the year's very best, while Zoe Thorogood seemed to create a profound creative refinement and synthesis. Juni Ba's work built onward and elevated itself from his spellbinding Djeliya, and we finally got a newly translated Vincent Perriot in English. And we also saw tremendous work this year from the likes of Pornsak Pichetshote, Ram V, and Linnea Sterte, who only seem to have grown over time.

Evolution has been the defining motif of the year for me, which shows perhaps in both Beaton's and Thorogood's works as well, reflective memoirs meditating upon transformations and change. Even Molly Mendoza's reflection on love and relationships feels like it fits into that. Everywhere we've been, and everywhere that we haven't... but yearn to be. It feels true looking even at something like Marjorie Liu's and Sana Takeda's tremendous kickoff of a graphic novel trilogy in the form of The Night Eaters (Abrams ComicArts), which marks a new endeavor for the longstanding Monstress duo. But I want to mention two creators in particular who really stood out for me and made a mark this year: Deniz Camp and Nadia Shammas. Both have been doing terrific work for some time now, but really cut loose and delivered in multiple bursts this year. Shammas with her OGNs with terrific collaborators Sara Alfageeh (Squire, Quill Tree Books/HarperCollins) and Marie Enger (Where Black Stars Rise, Tor Nightfire), and Camp with his periodicals alongside his striking collaborators Stipan Morian (20th Century Men, Image Comics), Filya Bratukhin (Agent of W.O.R.L.D.E., Scout Comics), and John Davis-Hunt (Bloodshot Unleashed, Valiant Comics). It felt like it was really their year of tremendous evolution, as what emerged was a far sharper expression of much of what their work had been reckoning with.

Beyond that, I loved Jump's best new manga series (the new Chainsaw Man is merely a sequel/continuation) of the year in the form of Yūki Suenaga's & Takamasa Moue's rakugo drama Akane-banashi (VIZ, translated by Stephen Paul). And I particularly enjoyed works like Jamila Rowser's & Robyn Smith's Wash Day Diaries (Chronicle Books) and Claribel Ortega's & Rose Bousamra's Frizzy (First Second), both of which center Black women and reckon with hair care. And like many, I too adored the new Cliff Chiang solo cartooning joint in Catwoman: Lonely City (DC Comics), which feels and reads like a breath of fresh air.

All in all? It was a fun year for the form. Here are the books I dug most:

-Ducks by Kate Beaton (Drawn & Quarterly)

-Little Monarchs by Jonathan Case (Margaret Ferguson Books/Holiday House)

-Monkey Meat by Juni Ba (Image Comics)

-20th Century Men by Deniz Camp, Stipan Morian & Aditya Bidikar (Image Comics)

-A Frog In The Fall (And Later On) by Linnea Sterte (Peow)

-Negalyod: The God Network by Vincent Perriot with Florence Breton, translated by Montana Kane (Titan Books)

-Stray by Molly Mendoza (Bulgihan Press)

-The Swamp Thing by Ram V, Mike Perkins, Mike Spicer & Aditya Bidikar (DC Comics)

-The Good Asian by Pornsak Pichetshote, Alexandre Tefenkgi, Lee Loughridge & Jeff Powell (Image Comics)

-Yokohama Kaidashi Kikou by Hitoshi Ashinano, translated by Daniel Komen, adaptation by Dawn Davis (Seven Seas Entertainment)

-Squire by Nadia Shammas & Sara Alfageeh (Quill Tree Books/HarperCollins)

-Where Black Stars Rise by Nadia Shammas & Marie Enger (Tor Nightfire)

-It's Lonely at the Centre of the Earth by Zoe Thorogood (Image Comics)

* * *

Derik Badman

1. Running Numbers (Pittsburgh 2) by Frank Santoro: An ongoing joy this year was regular mail from Frank, topped off at the end of the year by a hand-bound hardcover collection of this series of comics/zines. Ostensibly a sequel to his Pittsburgh, this is less structured and refined, an autobio zine that mixes neighborhood and family history alongside contemporary events. It's loose and beautiful, typed (as in typewriter) text on the verso with brightly sketched panels and images on the recto, all printed out on color xerox at home. It has the heart of an old school zine with the skill and style of experience.

2. King-Cat by John Porcellino: A perennial favorite, John never really surprises but he never disappoints either; simple drawings, wrapped in complicated feelings. There's always a strong sense of time for the reader of King-Cat, as the weight of decades of previous issues (and books) make John feel like an old friend one is catching up with at irregular intervals.

3. Speedy by Warren Craghead: Warren revived the name of his old Xeric-winning comic for a new series of his sui generis art. Issue 2 features brightly colored sketches from the Jan 6th coup attempt in a mode Warren's been using with a variety of other contemporary and historical political events, a kind of processing via pencil of trauma and sadness and anger. Issue 3 moves to the more personal and observational mode, with short comics and sketches of bike roads, family, and the beach - often attempts at capturing all the senses and feelings of life in images and (a sprinkling of) words.

4. Love & Rockets by Jaime Hernandez: I reread all of Jaime's "Locas" stories over a few weekends, from the early verbose sci-fi adventure stories to the most recent stories (that came out this year) of middle-agers dealing with changes in their lives. The overall effect is astounding; reading decades of comics in a short period of time compresses and accentuates the almost real-time aging of the characters. Sometimes I'd read a story, thinking how it seemed so recent, then see the date at the bottom and realize it was already 20 years old. There's always something new to see as one rereads old favorites; this time I was struck by the gaps Jaime inserts between some of the storylines. Suddenly time has passed (years even) and we only slowly (if at all) begin to understand how the characters and situations have changed in the interim, that missing gap of information often providing impetus for storylines.

* * *

Jason Bergman

My year in comics was largely informed by research I did for my interviews here at TCJ.

Rick Veitch's long-running Maximortal series is a history and satire of the comics industry, and Boy Maximortal (currently on issue 3) shows he still has something to say after all these years. He does so much work these days that it can be hard to keep track of it all, but I wish he would laser-focus on this series, because it's really the best work of his career.

Research for my interview with Mike Allred compelled me to go back and reread the entirety of Madman. While he hasn't created anything new in that series in many years, reading it all at once, I got a real sense of the arc of his life. It's rare to see someone work through their own personal issues on the page like that. I also read for the first time a sizable chunk of his Marvel work. His Silver Surfer series (written by Dan Slott) is the best kind of superhero book. Fun, gorgeously drawn, and utterly free of the confines of continuity.

Probably the best new book I read this year was Eric Powell's Did You Hear What Eddie Gein Done?, a collaboration with the true crime writer Harold Schechter (and also research for another interview). Powell has been a prolific and acclaimed creator for many years, but this is an exciting new direction for him. I loved everything about the book, from the gorgeous artwork to the conversational tone of the writing. Very much looking forward to their next collaboration.

I always use SPX as an excuse to hunt for new voices. This year I discovered the work of Elizabeth Pich, and have since been reading War and Peas, the webcomic she creates with Jonathan Kunz. I really appreciate the off-kilter humor in that one. Another SPX pickup was Aimée de Jongh's Days of Sand, a quiet and introspective book set during the Dust Bowl. That hadn't been on my radar before the show, and was definitely one of the best books I read this year. I met Caroline Cash at SPX, and picked up her Ignatz-winning book Pee Pee Poo Poo. She's young and still learning, but her work brought back memories of early Pete Bagge, Robert Crumb, and Roberta Gregory. She's got that same fearlessness, and is absolutely a talent to watch.

And lastly, 2022 was the year that Marvel finally started publishing Miracleman: The Silver Age by Neil Gaiman and Mark Buckingham. While it comes with dread that the character is going to be merged into Marvel's continuity, I've been waiting nearly three decades for this story to be finished, so this was really the comics event of the year for me. I poured over the first two issues like arcane manuscripts, trying to decipher every change from my original Eclipse copies, and at the end of this month the first new issue comes out. I can't wait.

* * *

Clark Burscough

One of the fun things, with ‘fun’ being a completely subjective quality, about writing TCJ’s links round-up each week, is getting to see the narrative play out in real time of which comic really hit big with the mainstream for a given year, in terms of sheer column inches devoted to its publication: 2020’s having been The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist by Adrian Tomine (Drawn & Quarterly); 2021’s The Secret to Superhuman Strength by Alison Bechdel (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt); and now 2022’s can be confirmed as Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands by Kate Beaton (Drawn & Quarterly), as recommended by former President Barack Obama. But this is not about his choices, it is about mine, and so on with the show we go.

Four books didn’t leave my desk, once I had them in my possession, despite their combined size, so, I think by sheer weight of time spent picking them back up, and flicking through to re-read, they get special mention as my favourites of the year: The Projector and Elephant by Martin Vaughn-James (New York Review Comics), a completely unknown author to me until this appeared, and completely beguiling once it did; One Beautiful Spring Day by Jim Woodring (Fantagraphics), which will join The Frank Book on my shelves, once I take just one more look through it when I can’t sleep, and maybe one more after that; My Badly Drawn Life by Gipi (Fantagraphics, translated by Jamie Richards), which spoke to me as someone who was an idiot in his youth, and never really moved on from that mode of being; and The Simpsons Treehouse of Horror Ominous Omnibus Vol. 1: Scary Tales & Scarier Tentacles (Abrams ComicArts), which I really hope sold well enough for the remaining two volumes to be printed, because it’s a handsome collection of comics, and it bodied me with a tidal wave of nostalgia every time I opened it, by taking me right back to said idiot youth.

A pair of books I read during my festive break, which I didn’t want to discount purely due to recency bias, as I enjoyed them a lot for completely different reasons, despite both being ostensibly in the horror space: Acid Nun by Corinne Halbert (self-published in comic book form, collected by Silver Sprocket), the accompanying writing to which from each issue connected me deeply to the story; and I Hate This Place Vol. 1 by Kyle Starks, Artyom Topilin, Lee Loughridge & Pat Brosseau (Image Comics), which was on the complete opposite end of the spectrum vis-à-vis traumatic horror, but the laughs and the gore both hit well, and the mystery contained therein is very spooky indeed.

My spandex-focused reading was pared well back this year, and I fully bought into that prestige hardcover edition lifestyle with Fantastic Four: Full Circle by Alex Ross, Josh Johnson & Ariana Maher (Abrams ComicsArts) and Catwoman: Lonely City by Cliff Chiang (DC Comics), the latter of which was far more interesting as a story than the former, but both passing with flying colors the ‘did I resist looking at my phone while reading them?’ test that most books from the Big Two stumble and fall at these days. Props also to One-Star Squadron by Mark Russell, Steve Lieber, Dave Stewart & Dave Sharpe (DC Comics), which made me finally track down and replace my old Justice League International trades and do a full re-read.

A pair of goodbyes hit differently in 2022, with the final volume of Ex.Mag edited by Wren McDonald (Peow Studio) arriving as the publisher comes close to shuttering its operations for good; and Vattu by Evan Dahm (self-published), which I had been reading for the entirety of its 12 years of serialization on the internet, and had as satisfying a conclusion as a melancholy story about colonialism and imperialism can have, especially when read in concert with the video essay on its making, leaving me excited to see where Dahm’s newly-started 3rd Voice will take readers.

Finally, my ‘read a manga series in its entirety’ pick for the year was Yotsuba&! by Kiyohiko Azuma (Yen Press, various translators), which was genuinely as funny as I’d been led to believe, and "Yotsuba & Vengeance" probably would have been the funniest comic I read in 2022, if not for the pure id of Blubber by Gilbert Hernandez (Fantagraphics).

* * *

RJ Casey

10.) Andros #9 by Max Clotfelter (self-published)

9.) "Winds of Change" by Eleanor Davis (New York Times)

8.) Washington White by Adam Griffiths (Secret Acres)

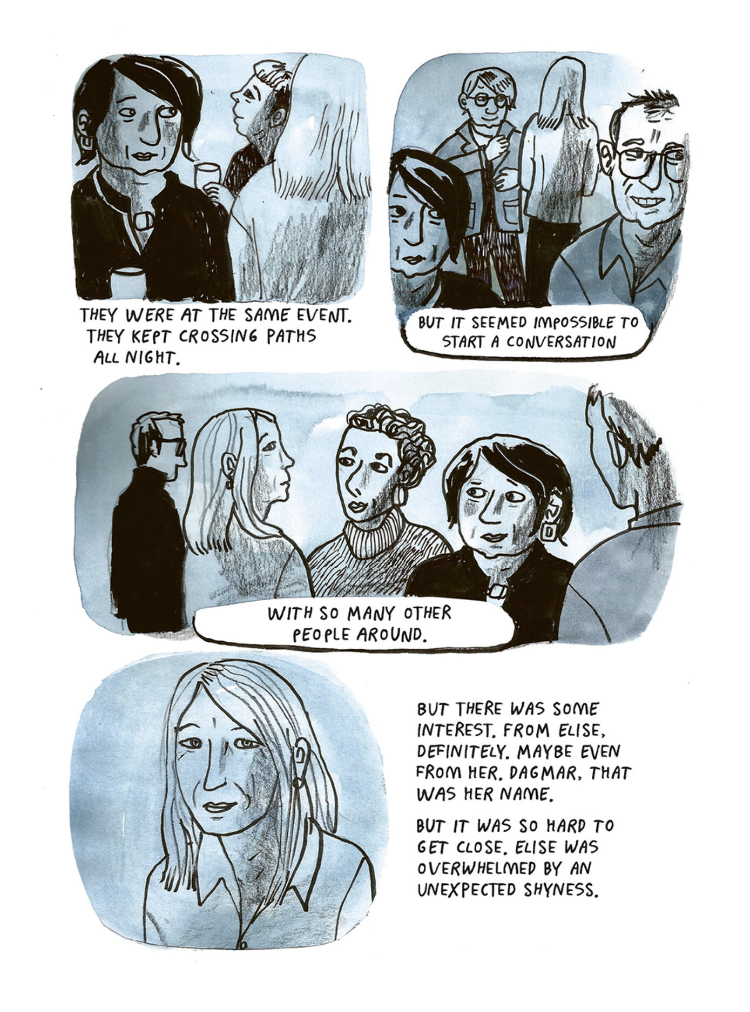

7.) Men I Trust by Tommi Parrish (Fantagraphics)

6.) Talk to My Back by Yamada Murasaki, translated by Ryan Holmberg (Drawn & Quarterly)

5.) Gray Green by Connor Willumsen (self-published on Instagram)

4.) Hypermutt #1-4 by Max Huffman (self-published)

3.) Blah Blah Blah #2-3 by Juliette Collet (self-published)

2.) Wild Vol. 1 by Cristian Castelo (Oni Press)

1.) Crickets #7-8 by Sammy Harkham (Commonwealth Comics Co. & Secret Headquarters)

* * *

Henry Chamberlain

The list will always be there to inform, entertain and to keep track of things. I find lists to be very useful and post a best-of-the-year list on my blog, Comics Grinder. The funny thing about a list is that you can keep adding to it or revising it as much as you want. But you need to stop at some point. So, here’s my most recent take on 2022, pared down to a Top Ten:

Acting Class by Nick Drnaso (Drawn & Quarterly)

This work finds Mr. Drnaso in his prime, perhaps pretty much content with the final results. I have come around to really appreciating what he’s doing. I was on the fence for a while. Many of us have our own reasons. For me, I didn’t really get his dropping the “h” in his using the word, “yeah.” Maybe I still don’t.

Chivalry by Neil Gaiman, Colleen Doran & Todd Klein (Dark Horse Comics)

I’m thinking this book needs some more love. You’ve got the A-Team of Gaiman and Doran and this whimsical tale hardly disappoints. Maybe it deserves to be revisited with my giving it a review in the new year.

Trve Kvlt by Scott Bryan Wilson, Liana Kangas, Gab Contreras, Jamez Savage & DC Hopkins (IDW Publishing)

If we love comics, then surely there’s a place for this gem: a celebration of the misfit warrior out in the world, attempting to fit in while plotting his escape. The creative team of Wilson & Kangas deliver with noteworthy deadpan humor.

Public Domain by Chip Zdarsky (Image Comics)

One more shoutout to the world of mainstream comic books. Zdarsky provides a satisfying low-key and offbeat tale of cartoonist underdogs taking on the big comic book publishing machine.

Domesticated Afterlife by Scott Finch (Antenna)

Here’s a fine example of a remarkable book that emerged one year and gained traction into the next. The many threads to this tale of worlds-within-worlds are masterfully handled by artist Scott Finch. My review is here.

Joseph Smith and the Mormons by Noah Van Sciver (Abrams)

Another monumental work that we’ll be talking about for many years to come. Van Sciver offers the reader the results of his lifelong searching on issues of faith.

G-G-G Ghost Stories by Brandon Lehmann (Bad Publisher Books)

Lehmann’s distinctive deadpan humor has been delighting a growing fanbase for years now. His star is rising and his work is available on various platforms. It was a pleasure to get a chance to interview him for my blog. My review is here.

Gnartoons by James the Stanton (Silver Sprocket)

A wonderful companion work to Lehmann's is this collection from fellow Seattle cartoonist James the Stanton. Zany and surreal stuff, just dripping with street cred.

Diego Rivera by Francisco de la Mora & José Luis Pescador, translated by Lawrence Schimel (SelfMadeHero)

This work is in the tradition of artful graphic novels about art and artists. It lives up to its promise and will transport the reader into the inner world of Diego Rivera. My review is here.

Schappi by Anna Haifisch (Fantagraphics)

It was my pleasure to delve into the work of Anna Haifisch and have an opportunity to share my findings with you earlier this year in my review. I also interviewed Haifisch for my blog. It was during our conversation that she mentioned the fact that cartoonists seem to be on a neverending treadmill of social media and she sort of envied the fact that Nick Drnaso doesn’t have any social media presence whatsoever. So, this brings us full circle back to Drnaso. I think he was spot on when he told the New York Times that he “fucking hated” his most popular book, Sabrina. I think what he meant was that he hated what can happen to cartoonists once they’re deemed worthy of notoriety. It becomes fair game to hype, overanalyze, tear down, and simply lose sight of the art form. But, with any luck, things have a way of falling into place.

* * *

Helen Chazan

This list is not in any particular order and is no way definitive. I have yet to have a year go by where I reached the end feeling that I had read every important new comic or every comic that might appeal to me. And then, of course, catching up the following year leads to me not reading enough new comics again! Shit. Anyway, I dashed this off pretty quickly so don’t take it too serious. Be well.

TIME ZONE J, Julie Doucet, Drawn & Quarterly

In a way this is the only comic. The story of a life.

DETENTION No. 2, Tim Hensley, Fantagraphics

A microcosm of history. We will be catching up with this for years to come.

IT HURTS UNTIL IT DOESN’T, Kahlil Kasir, Diskette Press

Deeply moving and emotionally honest self-portrait of a person living with chronic pain and traumatic grief. Kasir’s line is dissociative, distant, blunt and clinical, yet intimate and warm. If every Nick Drnaso book vanished overnight and was replaced by this little comic I think we would all be smarter and kinder people.

OROCHI, Kazuo Umezz, translated by Jocelyne Allen, adaptation by Molly Tanzer, VIZ Media

Comics about hysteria. Nobody depicts the perspectives of children quite like Umezz.

PLAZA, Yuichi Yokoyama, translated by Ryan Holmberg, Living the Line

The noisiest comic of all time. More on this soon.

BIRDS OF MAINE, Michael DeForge, Drawn & Quarterly

One of the truly great “pandemic response” comics. I am actually not very far into this comic because it’s just so pleasant to return to on the occasional morning. DeForge is one of the greats.

BOAT LIFE, Tadao Tsuge, translated by Ryan Holmberg, Floating World Comics

Tadao Tsuge’s very own The Man Without Talent, only his man does have one talent - or at least, a hobby. A comic about being old and rooted in place as the mind wanders. I keep returning to its misty terrain.

URUSEI YATSURA Vol. 16, Rumiko Takahashi, translated by Camellia Nieh, VIZ Media

Some of Takahashi’s best art. I appreciate how she begins to hint at giving her characters closure, although Urusei Yatsura cannot really have closure.

THE MUSIC OF MARIE, Usamaru Furuya, translated by Laura Egan, One Peace Books

Really outstanding manga that takes Furuya’s obsession with cute girls to a unique extreme. Worth returning to.

KAMEN RIDER: THE CLASSIC COLLECTION, Shōtarō Ishinomori, translated by Kumar Sivasubramanian, Seven Seas Entertainment

Oh lordy, if I had forgotten to mention this one I would have been kicking myself for weeks. Some of the most furiously cartooned shit I’ve read in a hot minute, chock full of silhouettes, harsh textures, endless momentum and intense action violence. Incredibly kinetic and surprisingly bitter journey full of creativity and ANGER. The titular rider is reduced to a brain in a jar midway through and has a homoerotic friendship with his successor via telepathy. Kamen Rider is just awesome.

BOOTY ROYALE: NEVER GO DOWN WITHOUT A FIGHT! Rui Takatō, translated by Jennifer Ward, adaptation by The Smut Whisperer, Ghost Ship/Seven Seas Entertainment

Wait what how did this get here? I’m sorry I am trying to delete it.

BOMBA!, Osamu Tezuka, translated by Polly Barton, Vertical/Kodansha

Evil Horse.

TALK TO MY BACK, Yamada Murasaki, translated by Ryan Holmberg, Drawn & Quarterly

A gekiga that I understand viscerally. A story about the claustrophobia of womanhood and the hope to transcend that life.

A FROG IN THE FALL (AND LATER ON), Linnea Sterte, Peow

Among other things, the best-designed book I encountered this year; work to be treasured.

INVISIBLE PARADE, MISSISSIPPI, translated by Anna Schnell, Jocelyne Allen, MISSISSIPPI, Andy Jenkins, Jun Kitamura and Emuh Ruh, Glacier Bay Books

I keep going back to these comics. MISSISSIPI is a very gentle and thoughtful artist.

MERMAID TOWN, Tomohiro Tsugawa, translated by Kristjan Rohde, Glacier Bay Books

Love love love love this. Dream comics are always special. Reminds me a bit of how Panpanya’s comics can wander out of place, or how Jim Woodring’s Jim treated dreams.

ONE BEAUTIFUL SPRING DAY, Jim Woodring, Fantagraphics

Speaking of Jim Woodring. Is it fair to call this a new comic? I hope it will not be overlooked. My only gripe is I do not understand why Weathercraft is not included; but then again, not understanding the Unifactor is part of the journey.

RIP MOU #2, V.A.L.I.S. Ortiz, Gatosaurio

I miss V.A.L.I.S. Ortiz. I hope she will be remembered.

* * *

Austin English

1. Time Zone J by Julie Doucet (Drawn & Quarterly)

In her last book, Carpet Sweeper Tales, Doucet told the audience to read the text out loud. In this book, she instructs you to read the bottom row of every page first and work your way upwards. And yet... Doucet isn't a cold formalist, she isn't making work that any honest person could label unapproachable - although even in progressive comics circles the book will be viewed as such, revealing layers of conservatism so ingrained in the medium's received ideas about itself that they are all but imperceptible to those who carry them. Doucet makes these choices not necessarily because they strengthen what she is trying to say, but, I suspect, because they make sense while creating her art, and allow the project to reach its conclusion. And this is important; it's important that this book was finished, because as a whole, it is the opposite of dry formalism, it is 'human' in a way that such a description can't do justice to. There is anger here, but not of the melodramatic sort; there's suspense but with imploded payoffs; there's beautiful drawing but none of it is meant to impress, exactly. It's a book about cycling through a particularly consequential encounter, and offering no resolution to it (because, though every other book of this type would deny it - honestly, how could you?). This withheld judgement does not bar a rich outpouring of genuine feeling, maybe from the author (I can only assume) but most notably for the reader. This comic doesn't rebuke most other comics for its formal daring, but instead shows how emotionally stunted most other works in this medium are in comparison. This might suggest that Doucet is 'wearing her heart on her sleeve'. No, instead she's expressing a complex range of thought and emotion in reaction to an event, the kind of complexity that this medium often tries to suggest is impossible even in the hands of the medium's greatest artists. We might recall Chris Ware wondering, decades ago, if it was possible to tell a story that approaches the emotional heft of Victorian novels in a medium designed to tell funny animal jokes. Well, this book answers the question, but obviously not through mimicry of other media. Many other graphic novels will top corporate publications' best-of lists and offer a play at adulthood; this book is made by someone who can only laugh against such a refusal of cartooning's capabilities.

2. Detention No. 2 by Tim Hensley (Fantagraphics)

Unlike Doucet, this work doesn't break with tradition. Instead it takes a trajectory 70 years in the making and tugs it so far ahead that the temptation, from a lesser artist, would be to explode things. Hensley comes close, but this is still a comic book. The book market is awash these days in Wikipedia-researched 'historical' graphic novels that flatly illustrate events in an uncritical manner, so committed to nothing in particular that they are almost avant-garde in their claim to be works of cartooning. Hensley, on the other side of the universe, is actually translating the texture of a novel into orthodox comic language... the panels here feel as if they are about to burst, overflowing with information and melodramatic charge, while (magically) eschewing excess.

3. Blood on the Tracks (ongoing) by Shuzo Oshimi (Vertical/Kodansha, translated by Daniel Komen)

Actually scary comics. North American non-superhero genre comics should take note of this series, as it sits on the shelves of every mainstream bookshop in the nation and offers more directly upsetting situations than decades of frustrated EC disciples have been able to provide.

4. Who Will Make the Pancakes by Megan Kelso (Fantagraphics)

Comics about internal compromise, the perceptible and imperceptible consequences of every single action you take, whether out of sacrifice or personal desire. Very sad, very hard-to-read, egoless comics that most people don't have the patience to make.

5. Blah Blah Blah #2 & #3 by Juliette Collet (self-published)

Genuinely exciting work that should appeal both to those who are deeply immersed in the promise of comics' potential and those who just want to read something exhilarating. While #2 was a very skillful black and white comic that would clearly impress even the stodgiest comics fan, #3 was full of artistic choices that showed a desire to make actual art rather than follow a predictable trajectory of radical-yet-sanctioned comics-making.

6. Orochi Vols. 1-3 by Kazuo Umezz (VIZ, translated by Jocelyne Allen, adapted by Molly Tanzer)

I read the Alex Ross Fantastic Four: Full Circle book this year, and while Ross finally managed to make his style breathe a bit more, I still felt dead after reading it. Skill in service of nostalgia, still, and the returns diminish, still. The example of an artist like Umezz, whose skill is unmistakable and vital, is more noteworthy than we might think. These are perfect worlds of cartooning that aren't stuffy or delicate but hyper-charged for involvement.

7. froggie.world by Allee Errico (Instagram)

Amazing comics that you can only read on Instagram. In a sane world there would be countless anthologies publishing Errico's work. I'm very intrigued by someone working at such a high level when the comics industry offers so few tangible rewards. Maybe 20 years ago this would be a weekly strip in alternative newspapers around the nation, with readers of all kinds encountering it without choosing to do so. As so many venues for viewing graphic work implode and tech apps soak up what's left (until they choose not to), work like this has an even stranger power. To make humane art at any moment in time in any venue is of value, but such a rich and rough work of art existing solely on social media is like a clip of German Expressionist cinema getting leaked onto the local evening news.

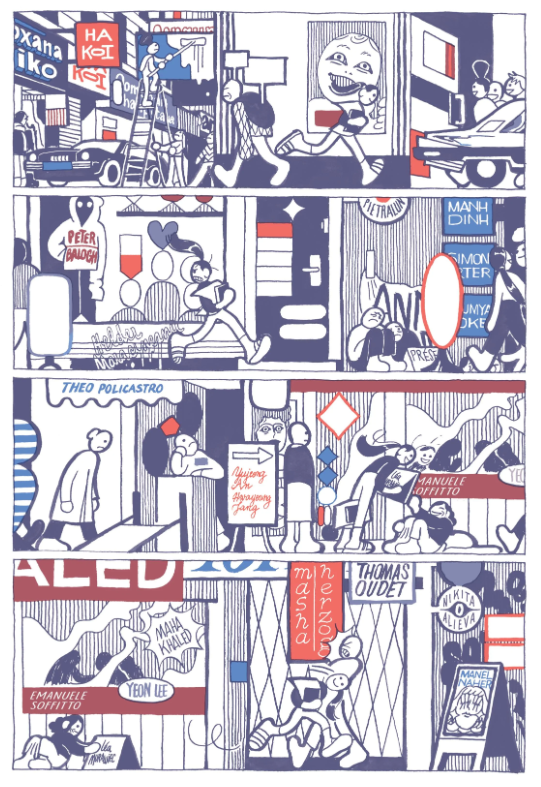

8. Cowlick Comics (ongoing), edited by Floyd Tangeman (Deadcrow)

The great Italian comics critic Gabriele Di Fazio described what Tangeman does with his anthologies in this way:

...for once we are not dealing with the copy of a copy, whether it’s of Olivier Schrauwen, Jesse Jacobs or Tara Booth. The feeling is that [these artists] have more to do than stay home reading the latest comic from Fantagraphics. And from these pages it comes exactly this, an incredible and unstoppable and irresistible urge to DO.

I run a company called Domino Books that tries to put many different visions of what cartooning can be in one place, in the hopes that all these different voices will destroy any coherent sense of rules that comics are supposed to live by. Comics are a form that can approach the idea 'art made by all' better than other kinds of art, but so rarely take this idea to heart. These anthologies do take such a notion to heart. They are essential publications to read if you feel your faith in comics dying, as there are dozens and dozens of artists in these pages that have already left you behind as you struggle to tell yourself you actually do like a copy of a copy.

9. Glaeolia 3, edited by Emuh Ruh & zhuchka (Glacier Bay)

I don't know how this publisher puts these anthologies together, but they are really doing English-speaking readers a great service by bringing together a wide section of highly beautiful alternative manga and printing it with real care.

10. Nightcore Energy by Morgan Vogel (Organ Bank)

This originally came out on 2019(?) and now the artist Pris Genet has re-published it. I've written about Morgan previously in these pages, but at that time it was all but impossible to direct unfamiliar readers to her work. I am extremely grateful to Genet for making this work available again, an unambiguously good thing to happen in 2022.

Honorable mention:

Richie Vegas Comics (ongoing) by Richard Alexander (self-published)

No one makes comics quite like this, I need to sit down and read this (now close to 1,000-page) saga before writing more about it, but I encourage everyone to take a closer look at this very unique cartoonist.

* * *

Andrew Farago

There were a lot of great books released in 2022, and it feels like creators are figuring out the work-life-pandemic balance and putting some Hall of Fame-caliber comics out there on a regular basis, and I love to see that. Here's a partial list of favorites from the past 12 months.

Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands by Kate Beaton (Drawn & Quarterly) is topping all of the year-end lists, and with good reason. I'll let others weigh in on that, as well as Love and Rockets: The First Fifty by Los Bros Hernandez (Fantagraphics Books).

All Your Racial Problems Will Soon End: The Cartoons of Charles Johnson by Charles Johnson (New York Review Comics) was a revelation. I have a real soft spot for those collections that show up completely out of nowhere to shine a spotlight on a little-known or completely forgotten creator, and this one is terrific.

In that vein, Maverix and Lunatix: Icons of Underground Comix by Drew Friedman (Fantagraphics Books) is already an essential text. Yes, you get Friedman's incredible illustrations, yes, you get all the usual suspects like Crumb and Rodriguez and Robbins, but Friedman takes a deep dive into underground history and covers the lesser-known creators, publishers, and weirdos who made the movement what it was. And is. A living, breathing history from a creator who's been making such great artwork for such a long time that I hope nobody's going to take him and this book for granted.

Chivalry by Neil Gaiman, Colleen Doran & Todd Klein (Dark Horse) is a beautiful, beautiful book. I was privileged to curate an exhibition of Doran's original artwork for Chivalry at the Cartoon Art Museum earlier this year, and I really hope everyone manages to see her paintings in person if they're able to do so when the Society of Illustrators in New York hosts their Colleen Doran retrospective next year. The story's sweet, too.

Wash Day Diaries by Jamila Rowser & Robyn Smith, with Bex Glendining & Kazimir Lee (Chronicle Books), was a sweet day-in-the-life comic, and I want to see more comics from Rowser and Smith, separately and together.

The Human Target by Tom King, Greg Smallwood & Clayton Cowles (DC Comics) reminds me that there's nothing like watching a smart, suspenseful mystery play out one installment at a time during its original serial release. Not surprised at all that I'm enjoying King's writing, but Greg Smallwood just came out of nowhere and made this one of the most striking DC books in recent memory.

The Last Mechanical Monster by Brian Fies (Abrams) was a standout webcomic, and I'm glad to see it in a really sharp print edition. If only all Superman-inspired comics could be this fun and inventive.

* * *

Gina Gagliano

Some of the Best

Graphic Novels I Read in 2022

Featuring Queer Women

Flung Out of Space, by Grace Ellis & Hannah Templer (Abrams ComicArts)

Authors are some of the coolest people I know, so I’m always excited to come across a new author biography. (Especially when they’re about queer women. Especially especially when they’re queer women who are also comics authors. Especially especially especially when they’re in comics format!) Patricia Highsmith was extraordinarily cool, and Grace Ellis & Hannah Templer do a fantastic job depicting her life as an author - and her struggles to be the kind of author she wanted, and to live the kind of life she wanted.

(This book also contains a cameo from Stan Lee, if you like that sort of thing.)

The Real Riley Mayes, by Rachel Elliott (Balzer + Bray/HarperCollins)

You know how when you’re a kid and you’re queer and it’s really awkward and you don’t know what to do or how to behave? This book is that, right in your face all the time, as Riley figures out she likes girls, doesn’t know how to talk about it, and then ends up (accidentally) telling absolutely everyone. Luckily, with the help of some sleepover Pictionary, letters from a celebrity comedian, and good friends, everything turns out less stressful than expected.

Wash Day Diaries, by Jamila Rowser & Robyn Smith (Chronicle Books)

Jamila Rowser’s & Robyn Smith’s gorgeous, thoughtful book depicts a day in the life of four Black women - with stories that orbit around hair, but also romance, family, and friendship.

The character Cookie’s story in particular has some great intergenerational conversation (and long-awaited grandmotherly acceptance for her queerness). I love how this story shows a road from homophobia to understanding.

Still Sick, by Akashi (Tokyopop, translated by Katie Kimura)

This graphic novel is SO cute. So, so cute. Also it’s about what to do when your coworker discovers your side-career making very, very, very gay fancomics.

(The answer is: fall in love, and support her own comics-creating dreams.)

Thieves, by Lucie Bryon (Nobrow)

The premise of this book is, what do you do if you have a crush on a girl and get extremely drunk at a party at her house and then wake up at home to find out you’ve stolen some of her things? Many hijinks ensue from there (including friends, childhood bullies, and tutoring), and they’re all delightful.

The characters’ ears are especially good (all of Lucie Bryon’s art is lovely and adorable). Also there’s a heist. And they ride on a bicycle together.

Mamo, by Sas Milledge (BOOM!)

Sas Milledge’s art is absolutely fantastic!

This book is a story about coming home to figure out the best place to belong - and finding potentially sinister magic seeping into everything that it’s somehow your responsibility to resolve, all while dealing with a new friend (and possible crush).

Other Ever Afters, by Melanie Gillman (Random House Graphic)

This book has so many queer women. So, so many.

There are giants, mermaids, knights, princesses, goose girls, foresters - young women and older women, women starting out on quests and women staying home, royalty and tavern maids. It’s just the best, and everyone is drawn in Melanie’s gorgeous colored pencil artwork.

(Disclaimer: I edited this book, and I think Melanie is one of the most amazing cartoonists working today. All their work is fantastic, and you should check it out!)

* * *

Matteo Gaspari

Despite trying to keep up with what’s going on outside my little country, I read and write from Italy, and therefore I’m inevitably more in touch with our domestic production. So I thought I could try to do a brief personal list of “cool (not necessarily Italian) comics published in Italy during 2022”, knowing some things are yet to be translated in English (but hoping they’ll soon be!).

To be honest, this year Italians saw and read a lot of cool stuff: long-awaited masterpieces, such as Chris Ware’s Building Stories (Coconino Press/Fandango) and the last chapter of Joann Sfar's and Lewis Trondheim's La Fortezza, aka "Dungeon" (Bao Publishing); the return of great artists such as Manuele Fior with Hypericon (Coconino Press/Fandango) and Paolo Bacilieri, who adapted Giorgio Scerbanenco's noir novel Venere privata (Oblomov Edizioni); and Gipi taking a break from his more serious work and going full mad with the sci-fi divertissement Barbarone (Rulez). These books I did not included in the list - not because I didn’t like them, or because I don’t think they’re relevant (ça va sans dire), but maybe they’re in a way less surprising? For me, at least.

I also excluded a priori the comics I published myself, because it sounded too much like conflict of interest, but I’m nonetheless very proud of each of them and think they’d deserve at least a shoutout. So thank you Sara Garagnani, Linnea Sterte and M.S. Harkness for being the first blocks of an imprint I’m so happy to see growing every day!

With that said, here we go. In no particular order:

Keeping Two by Jordan Crane (Oblomov Edizioni; in English from Fantagraphics)

Such a great book! This visually stunning exploration of loss and the hysteria generated by the fear and anxiety of potential loss was, I think, one of the best things that happened to graphic novels this year. I understand Lane Yates' criticisms of the book–and I’d direct you to their very interesting critique–but I don’t quite share it, especially when it comes to the formal aspects of the book: its way of intertwining reality, hallucinations, fiction-within-fiction, regrets and (dark) desires. So elegant and on-point, so unapologetic in its seemingly (but just seemingly) basic use of the language, which conveys layered meaning without turning into a mannerist exercise.

Anche le cose hanno bisogno by Eliana Albertini (Rizzoli Lizard)

As a narrator of the provincia–that particular anthropologic and urbanistic state of being which is not city nor rural countryside–the author already proved her worth in her previous book, Malibu. But this one is just on another level.

Agnese, the protagonist, obsessively collects broken things. Actually, “obsessively” and “collects” are not the proper terms: she takes care of them. Hence the title of the book, which would roughly translate to something like “Even Things Need”. They don’t need this or that, they just need. Even though they are things. There’s this non-anthropomorphic humanizing feel in the way Agnese take care of broken things that’s simply moving. It’s a book that reminds me that everything needs. Even things. (Which implies: not just things.)

Eldorado by Tobias Tycho Schalken (Coconino Press/Fandango) & 2120 by George Wylesol (Coconino Press/Fandango; in English from Avery Hill Publishing)

Coconino Press has undergone a rebirth of sorts this year. And that’s partly because of a new sub-imprint called Brick, directed by former editor-in-chief Francesco D'Erminio, aka Ratigher. Paraphrasing the publisher: Brick’s books are meant to be metaphorical bricks thrown to the readers (in honor of the more literal bricks Ignatz throws at Krazy Kat). And let us have more bricks-in-the-face like these!

Eldorado, by Dutch artist Tobias Tycho Schalken, is a collection of short stories, photos, artistic instalments, and metaphysical reasonings. A book that looks like a conceptual artbook itself and reads like one of the most interesting, lateral and thought/emotion-provoking pieces on the ending of all things, on the meaning of it all.

2120 is a choose-your-own-adventure visual treat about a computer technician sent into a seemingly empty building from which escape feels impossible. The reader's convoluted navigation through the pages mimics the growing frustration of the protagonist, stuck inside a backroom - a liminal space that is, and at the same time isn’t. The book has this delicious hauntology vibe, this decadent vaporwave-meets-low key cyberpunk aesthetic, and it plays like a janky LucasArts point-and-click adventure... to which it can be equally frustrating, adding to the overall experience!

If Coconino’s Brick intends to show us what comics are, or can become, this is the right way.

Il grande vuoto by Léa Murawiec (Comicon Edizioni; forthcoming in English from Drawn & Quarterly)

I was particularly excited when Muraweic’s book was translated. Partly because it’s the first book by French publisher Éditions 2024 to be translated in Italian. (If we exclude Tom Gauld’s masterpiece Mooncop, which I think came out from Drawn & Quarterly first anyway.) And Éditions 2024 is a great, great publisher. Check it out! But I was also excited because Il grande vuoto, original title "Le grand vide", is a great book.

Visually stunning, with images strong enough to jump off the paper, Murawiec's debut(!!!) is the tale of a girl living in a world where notoriety literally means survival: your life expectancy is dependent on how many people know your name and think of you. As a reflection on societal narcissism with a touch of social network critique, it’s not exactly something new. But Murawiec takes the lesson of something like Andrew Niccol’s film In Time or Black Mirror’s start-of-the-decline episode "Nosedive" and simply… does it better.

Il grande vuoto reads amazing, is visually incredible, and is coherent in its worldbuilding and character development to a fault. Lastly, shout out to Comicon Edizioni for doing it the proper way: hardcover, and big as the original.

La tempesta by Marino Neri (Oblomov Edizioni)

I've always felt that comics, especially in their graphic novel form, have a problem with brevity. A lot of graphic novels lack the density and complexity of a novel, so they read more like diluted short stories that lack the clarity of scope that should characterize them. Marino Neri’s La tempesta nails it. It’s not a novel; it doesn’t try to be. We see characters we know little to nothing about at a pivotal moment of their lives - we see them change over one stormy night, and then we move on. It’s a strong, almost archetypal story that knows the power of the fragment and knows not to waste time and space to appear (but just to appear) more complex.

Flannery O’Connor defines a short story as a complete dramatic action, in which characters unveil themselves through the action itself. In this sense, La tempesta is a proper short story, one that draws strength from the unseen and the unspoken. A story to read and read again, to derive a meaning so clean and powerful, yet so elusive. A stunning book that shows us what the usual 140-something page graphic novel can be when it stops trying to be a novel.

Cervello di gallina by Silvia Righetti (Coconino Press/Fandango)

It’s kind of rare, at least in Italy, to see a debut work from a young author that deviates from the much more common autobiographical or autofiction, reality-based story. Silvia Righetti instead tells the story of an inventor who tries to connect to the mind of a chicken in order to communicate with aliens, and of his sister who is left to deal with this mess of an obsessive brother alongside a boyfriend probably dead in the bunker where he sheltered himself in fear of said aliens.

It’s a book about paranoia and conspiracies, about losing touch with reality, about ambition and… a lot of other stuff. A book that could’ve been a nightmare to read (given its complex and claustrophobic layout) and instead flows marvelously; a book that feels a bit like David Cronenberg’s Crimes of the Future, and a bit like Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s Delicatessen.

Eternity Vol. 1 by Alessandro Bilotta, Sergio Gerasi & Adele Matera (Sergio Bonelli Editore)

It’s no surprise that Alessandro Bilotta is probably the most interesting of Bonelli’s writers. But this first volume of Eternity still exceeds expectations in every possible way. With the drawings of Sergio Gerasi and hard-to-believe colors by Adele Matera, this book is something like Paolo Sorrentino’s The Great Beauty, but with no restraint.

Alceste Santacroce, a proper dandy, is a gossip journalist in a Rome so stylish you’d wish it existed. Through his shamelessly elegant and unapologetic lifestyle, and the series of encounters that follow, we witness a metacommentary on nihilism, on the thirst for meaning, on narcissism, on vengeance and retribution. It’s just the beginning of what I hope to be a long and fruitful series, but it’s a jaw-dropping beginning, with some of the most interesting sequences in terms of layout and reading flux I’ve seen in a while. Which is doubly surprising given Bonelli’s reputation as one of the most “aesthetically conservative” publishers out there.

* * *

Charles Hatfield

Following is a baker’s dozen of personal faves from 2022. For me, it’s been a year marked by long-awaited works from revered creators: Doucet, Crane, Beaton, Woodring. Known alt-comix publishers, especially Drawn & Quarterly and Fantagraphics, have drawn my attention - though certain small-press and self-published works have grabbed me too. While I’ve binged on a few series from DC and Marvel via their respective apps (late-night reading, with blurry eyes), none of those stand out as faves. Likewise, I’ve followed a few direct market serials, but only one leaps out as a keeper (see below). Frankly, I’m surprised that my list does not include any graphic novels aimed at children or young adults - something of a specialty of mine, but one I’ve sadly lost touch with lately. I’m also sheepish about the near lack of manga and total lack of webtoons here.

For sure, I’ve missed a lot of good stuff this year. This very week, just before my deadline for this piece, I hit up some of Los Angeles’ best book and comic shops and discovered a stunning bonanza of titles from 2022 that I ache to read. I took a lot of notes and photos. The sheer profusion of interesting comics on offer is intimidating. I often tell my students that “comics doesn’t sit still,” that I have a hard time keeping up, and that that is a good thing. Yes. But I feel a bit avalanched under this year - which means I feel an odd mix of delight and frustration. What I have been able to read in 2022 has been a gift.

Since I tend to binge on recent comics during the intersessions (I’m an academic), I expect that in a couple of weeks I’ll have a much longer list of faves from this past year. That’s how it goes. In the meantime, here’s that baker’s dozen:

Big Gorgeous Jazz Machine, by Nick Francis Potter (Driftwood Press). I greatly enjoy this collection of abstract, semi-abstract, and lyrical strips. The dozen works gathered here are disarmingly accessible - not so much hermetic headscratchers as invitations to engage. Many (not all) use the repetitiveness of regular grids to good effect; many (not all) scatter words and letters across their panels, discombobulating language more artfully than most comics do. The results are playful and disorienting, and usually yield some kind of synapse-crossing “Aha!” when I put in the effort. The book is an aesthetic delight: Some of the strips/poems are penciled only, while others boast vigorous colors (ink, crayon, paint). Some are simply about morphing shapes, while others are bursts of lyric, tending toward the observational and/or impish. “After the President”, an ironic “inauguration poem” conceived in 2016, is barbed and scary, a fevered political nightmare. Potter cites experimental cartoonists like Warren Craghead, Aidan Koch, and Simon Moreton as kindred spirits; Philip Guston is in the mix too, and at times I was reminded of Marc Bell (though I wouldn’t presume to say that he was an influence). To ask whether this is a book of comics or a book of poetry would be to miss the pleasure of mixing the two. From now on, I’ll follow Potter wherever.

Birds of Maine, by Michael DeForge (Drawn & Quarterly). This book collects DeForge’s webcomic, which I had missed. In this absurdist utopian satire, birds from Earth have settled in a colony on the moon, where they maintain their own complex society and technoculture while also, sometimes, researching the culture of humankind (which tends to appear stupid and sad by comparison). The arrival of a human astronaut seems to promise big changes, but no, the birds carry on in their own way, while DeForge takes whimsical narrative detours, chasing seemingly tossed-off ideas into profound territory. Spiky and minimalist art, sharp, flat colors, and an unvarying structure (each page is a separate strip, identically laid out) gradually build a thought-provoking secondary world that argues with our own. All this is dryly humorous, but then again queerly lovable, and mostly avoids the obvious in favor of the unexpected. I’ve never read another comic like it.

Career Shoplifter, by Gabrielle Bell (Uncivilized Books). A funny and affecting booklet about life in cafés, this mixes Bell’s observational autographic strips—about overhearing, spying on, or sometimes interacting with other café patrons—with beautiful spot drawings of such folks. Bell’s sharp eyes and unerring sensitivity imbue these mini-portraits with life, while her fretful, quietly desperate persona adds hilarious, but then again poignant, overtones. Occasional dreams or other nervous digressions punctuate these strips, but mainly this is about hanging out, maybe judging, maybe not, and sometimes just feeling awkward. The drawings comprise a terrific gallery of types, precisely rendered in Bell’s rumpled, unkempt, but in fact staggeringly accomplished style. I’ve spent many hours in cafés, mostly grading papers and watching other people write, read, scheme, and schmooze - Bell nails the odd intimacy, yet anonymity, of those places. Career Shoplifter reminds me of how guilty, yet entranced, I sometimes feel when riding shotgun on other people’s reveries or conversations. A weird gem.

Ducks, by Kate Beaton (Drawn & Quarterly). Of course - this book is downright heroic! An autographic rendering of Beaton’s two years working in Canada’s oil sands, Ducks walks a wire between firsthand memoir and political indictment. It’s a tremendous leap for Beaton in terms of scope and ambition, demanding a huge range of individual likenesses and settings and a keen, selective eye for the telling detail. The book conveys both a melancholic longing for Beaton’s home (Cape Breton, here a focus of diasporic nostalgia) and a furious recognition of the inhumanity, especially the ambient misogyny, of the oil industry: one fueled by a rapacious, untrammeled capitalism that tears people from their social moorings in the name of profit and opportunity. This workplace culture clearly taught Beaton a great deal but also enraged and wounded her. Sad, often infuriating, sometimes wrenching, Ducks is miraculously funny too, with flavorful dialogue, wry absurdities, and stinging ironies. Beaton cartoons brilliantly, and works mightily to communicate a complex reality. The final scene is understated and ends in mid-air, but in context hits like a hammer. The book’s many passing characters and social subtleties practically beg for a rereading.

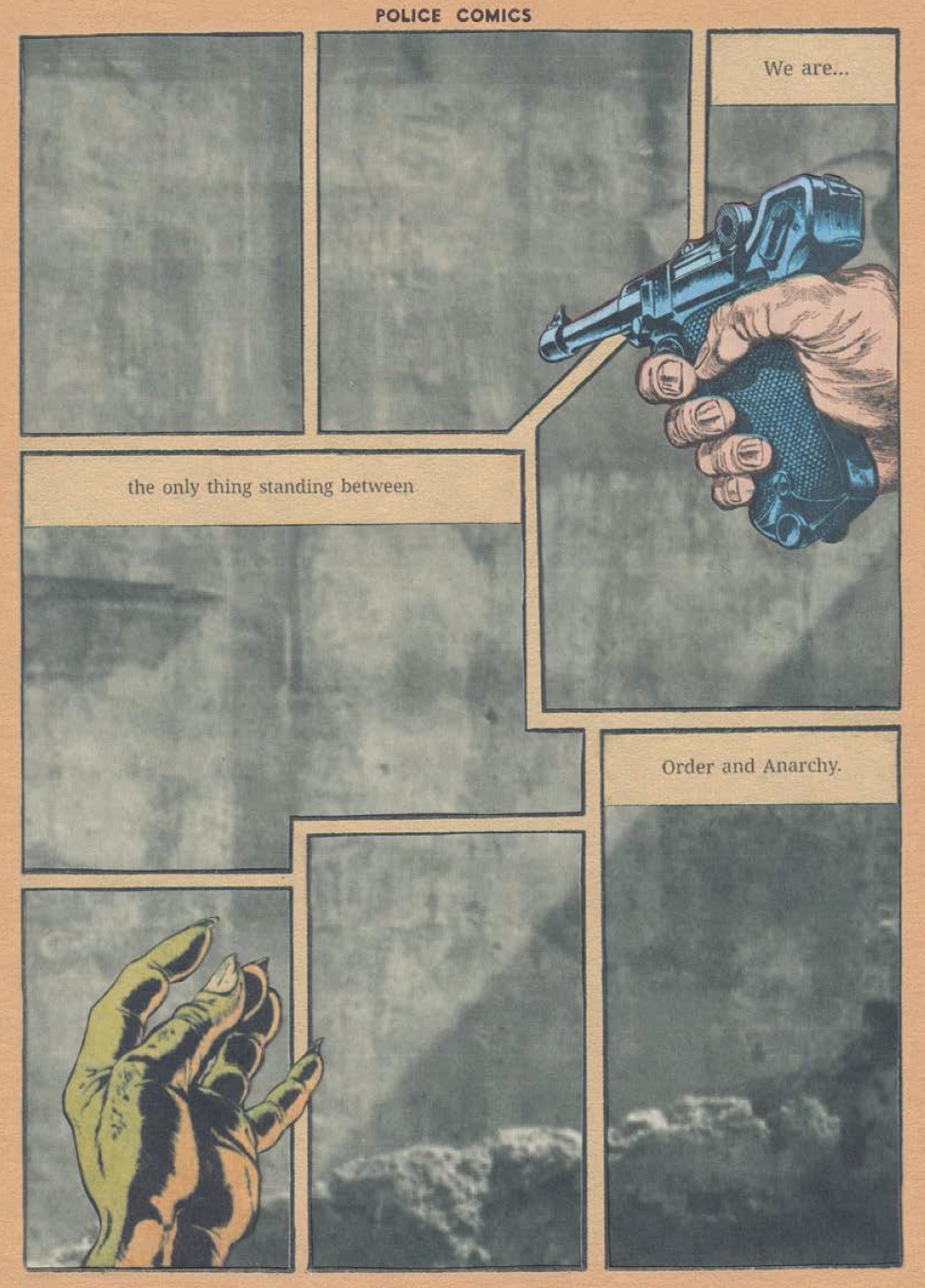

"I’m a Cop": Real-Life Horror Comics, by Johnny Damm (self-published). More comics poetry. Dreamlike and confounding, this booklet mashes up received materials in an unnerving way. Damm détourns images and layouts culled from pre-Code comics, giving them vague black-and-white photo backgrounds; then, crucially, he anchors the resulting pages with appalling quotations from current or recent police union leaders. Those statements, in their matter-of-fact authoritarianism and embrace of violence, freeze the blood. Damm’s combinatorial work recontextualizes and reactivates familiar genre tropes and twice-seen images; the results have a needling urgency. At once politically necessary and formally cool, "I’m a Cop" offers visual poetry with teeth. I’m teaching this next semester.

Joseph Smith and the Mormons, by Noah Van Sciver (Abrams). Treading the proverbial knife’s edge between sympathy and judgment, this graphic biography is a remarkable feat of dispassion, insinuation, and, above all, aggrieved tenderness. Van Sciver’s own childhood history with the Church of Latter-day Saints seems to animate this project, but the result is neither a saint’s life nor a polemic. Avoiding intrusive narration, Van Sciver lets us draw our own conclusions. At times, I sympathized; at times, I fretted or raged. I would call the book a debunking, but that isn’t accurate; it’s more of a demystifying (while still granting space to mystery). The story it tells is morally confounding, and in that sense challenging; its quiet epilogue slays me. Beautifully drawn, this is the best book yet from a great and underrated cartoonist.

Keeping Two, by Jordan Crane (Fantagraphics). A single evening’s story, disarmingly intimate, about invasive thoughts and anxious fantasies that coalesce into a few frightful hours of imagined losses and real terror. A young couple, home from travel, exhausted and tense, in love but also at odds with each other, experiences a night of emotional turbulence - even though, outwardly, nothing seems to happen (at first). Classical and restrained, governed by certain firm house rules, this graphic novel nonetheless overflows with tenderness, harrowing suspense, and gorgeous design and drawing. The color green has never looked so versatile. I’ve read chapters of this story over the years, but what a gift it is to have all the story gathered into one volume, at last. The story’s home stretch makes my pulse race, and, overall, the book wrings me out like a rag. That’s what I call a real reading experience. I taught Keeping Two this past semester, and I’m teaching it again in the spring.

One Beautiful Spring Day, by Jim Woodring (Fantagraphics). Improbably, Woodring has expanded three existing books in his Frank series, reshaping them into one sprawling epic that feels different. This shouldn’t work: famously, the wordless Frank yarns come to Woodring semi-automatically, and past efforts to discipline that particular muse haven’t worked out well for him. But One Beautiful Spring Day, a 400-page pantomime full of callbacks and narrative recursions, somehow reconciles automatism and craft beautifully, and makes old work feel new. I sat down with this one on Boxing Day and re-gifted it to myself. I chuckled, I guffawed at times, and, then again, I blanched with horror, repulsed by the offhand violence and continual suffering of Frank and his fellow critters. It was all so pleasurable - and I felt sort of guilty for the pleasure I took. The book is cruelly hilarious: such terrors for Frank and company; such anguish and confusion. Woodring’s drawing is, as ever, hypnotic and splendid, full of staring eyeballs, dream architecture, and blessedly ugly creatures. The terrors and shocks come like Satori moments, piercing and transformative, but are followed by, of course, more passages of blind stumbling and obtuseness, since Frank does not know what the hell he is doing or why it matters. Glory! I’ve been thinking and writing a lot about Woodring lately, so this book really does feel like a gift.

Sea of Time #1, by T Edward Bak (Floating World Comics). I can’t tell whether this is a continuation, companion, or sequel to Bak’s Island of Memory, a nearly decade-old (2013) graphic novella with the same subject: Georg Steller, the 18th-century German naturalist who traveled under the aegis of the Russian Empire and explored Alaska and Kamchatka. Bak has been obsessed with Steller for years, and has long promised a complete graphic biography of him under the title Wild Man. He has referred to Sea of Time as the second volume of Wild Man, but also as “the serialized graphic novel follow-up to Island of Memory.” I don’t get how the two books fit together, or what is supposed to come next. What I do know is that both books are lovely, and that, taken by itself, Sea of Time is hermetic and hard to parse, but stunningly beautiful and transporting. I’m glad that more Sea of Time is promised, because no one else is doing quite what Bak is doing at the intersection of comics, history, and the natural sciences. He treats comics as a way to feed his knowledge of the natural world yet is likewise alert to the political and cultural snares inherent in his subject matter, especially the fraught interchange between imperial and Indigenous ways of knowing. Bak’s sharp, rugged style somewhat evokes the woodcut technique of early Russian lubki, which could be either an apt or ironic framing of the imperial adventurism that underlies Steller’s story. In any case, Bak’s art is getting lovelier, and his graphic worldmaking is something to behold. At only 24 pages, this booklet makes me impatient to see more!

Step by Bloody Step, by Si Spurrier, Matías Bergara & Matheus Lopes (Image Comics). More wordless storytelling. This was my craftalicious DM serial of early 2022: a mute fable about the wanderings of a ragged, vulnerable child and her huge, armored guardian in a cruel and colorful fantasy world. Graphically lovely, it has pages worth putting the brakes on for - or, more to the point, worth rereading and gawking at. The story is ambitious, meaning that it attempts some very complicated plotting despite its wordlessness. Family, growing up, desire, and regret are involved. War and slaughter too. There is dialogue, in the form of teasing hieroglyphs that read as asemic to me but may be code. Does it all work? I can’t be sure. In the home stretch, the tale twists and gets harder for me to follow; the plot impels me to replay and reconsider what has come before. The ending bewilders, a bit, though in that intriguing way that makes me glad for the experience. The drawings, by Bergara, and the coloring, by Lopes, stun.

The Stoneware Jug, by Stefan Lorenzutti & John Porcellino (co-published by Nieves, Bored Wolves, and Spit and a Half). Poetry again! I’m always gladdened by a new dose of John P., and this year has brought three: the latest issue of his enduring King-Cat (#81); then The Collected Prairie Pothole (from Uncivilized Books), a gathering of his short Midwestern memory strips; and, most recently, this beautifully spare 24-page booklet made up of collaborations with the Poland-based poet and micro-press publisher Stefan Lorenzutti. It marks an unusual publishing collaboration between Porcellino, based in Illinois; Nieves, a micro-press out of Zurich; and Lorenzutti’s Bored Wolves, more or less based in Kraków. Consisting of 13 of Lorenzutti’s short poems, adapted into comics by John P., The Stoneware Jug is plainspoken, lyrical, and lovely. Poet and cartoonist are the proverbial match made in heaven. The resulting visual poetry, observant, wry, and epiphanic, hits close to home. The sheer emptiness and quiet of the pages amaze me. This feels like art for cool gray days, or biting cold nights, but it’s full of life, and I could read it over and over with pleasure. In fact, I have.

Talk to My Back, by Yamada Murasaki (Drawn & Quarterly, translated by Ryan Holmberg). Serialized in the now-legendary Garo between 1981 and 1984, this manga captures the mature style of Yamada, a mix of airy minimalism and unerring observation. The stories, or episodes, concern motherhood and marriage - more to the point, the struggle to reclaim a self within an institution that is patriarchal, hopelessly idealized, and suffocating. These were radical comics despite, or rather because of, their unvarying domesticity, visual understatement, and minute evocation of everyday things. They remain pointed and convincing, startling in their frankness, and beautiful. Yamada writes complexly about relationships; she has much to say about the naïve expectations men and women have of each other and the crushing unevenness of responsibilities within marriage. She also has a sharp eye for the complex tenderness between parents and children, the ethics of parenting, and the heavy toll that intensive parenting can take. Talk to My Back is about “waking from the dream” - I’d say about claiming a kind of freedom. Yamada claims her own freedom with pages so spare that they border on emptiness; physical settings are merely gestured at, and faces often disappear. But the cartooning is sharp. This is a wonderful volume of manga and manga history, superbly rendered into English and contextualized by translator-essayist Ryan Holmberg.

Time Zone J, by Julie Doucet (Drawn & Quarterly). A dizzying experiment in form, bookness, and autobiographic presence - in fact, a genuinely new approach to autobiographical comics, in the form of one continuous drawing, folded and bound into a nonstop canvas that we can never see all at once. Doucet’s drawn avatar multiplies on the page(s), reminding us that memory takes place in the here and now. Past and present blur, confounding any straightforward reading. The pages read peculiarly, defying standard directionality and demanding a very self-conscious kind of navigation. The paraphrasable content of the story, romantic and desperate, says less to me than the way the book’s format defamiliarizes the reading experience - but of course that has everything to do with the story too. On top of everything else, this is a great feast of drawing, teeming with particularized portraits of diverse women, overlapping, vivid, and charged with life. This book, which fairly bent my head, fulfills one of the maxims I like to repeat in my classes: comics is about making reading strange again.

* * *

Tim Hayes

*Olympia (Fantagraphics, translated by Montana Kane)

The story from The Grande Odalisque by Jérôme Mulot, Florent Ruppert and Bastien Vivès continues into what Netflix would call Season Two if it had signed Adèle Exarchopoulos to play high-strung heartbroken thief Alex for a sexy Francophone binge watch, Luc Besson's lewd lesbian Lupin. Horny criminals doing horny crime on a horny continent means horny comics.

*Project MK-Ultra: Sex, Drugs & the CIA Vols. 1 and 2 (Clover Press)

Based to some degree on a film script by others but turned firmly into a comic by writer/artist Stewart K. Moore. Political comics don't have to look like photocopied modernism Sellotaped to the walls of a basement; this one is lush bulbous chromatics and Jack Davis caricature and Spike Milligan absurdity at the rotten heart of the American century.

*Graveneye (TKO Studios)

Sloane Leong's 2017 comic A Hollowing was Gothic horror wielding a scalpel. Graveneye, written by Leong and drawn by Anna Bowles, is Gothic horror wielding a wood chisel.

*Kris Kool (Passenger Press, translated by Clara Longhi) and Doctor Strange: Fall Sunrise (Marvel)

Caza's 1970 psychedelic trip, reissued for our moment of total subjectivity and culture war and environmental collapse. Art piling on visual resonances and amplifiers of consciousness; art saying that another world is possible, not by trying to draw one, but by summoning up the principle in a reader's mind. Doctor Strange: Fall Sunrise materializes in 2022 as if called forth in response, Tradd Moore (colored by Heather Moore) seeing how a Caza covers band sounds; still a great tune, but the original has the soul.

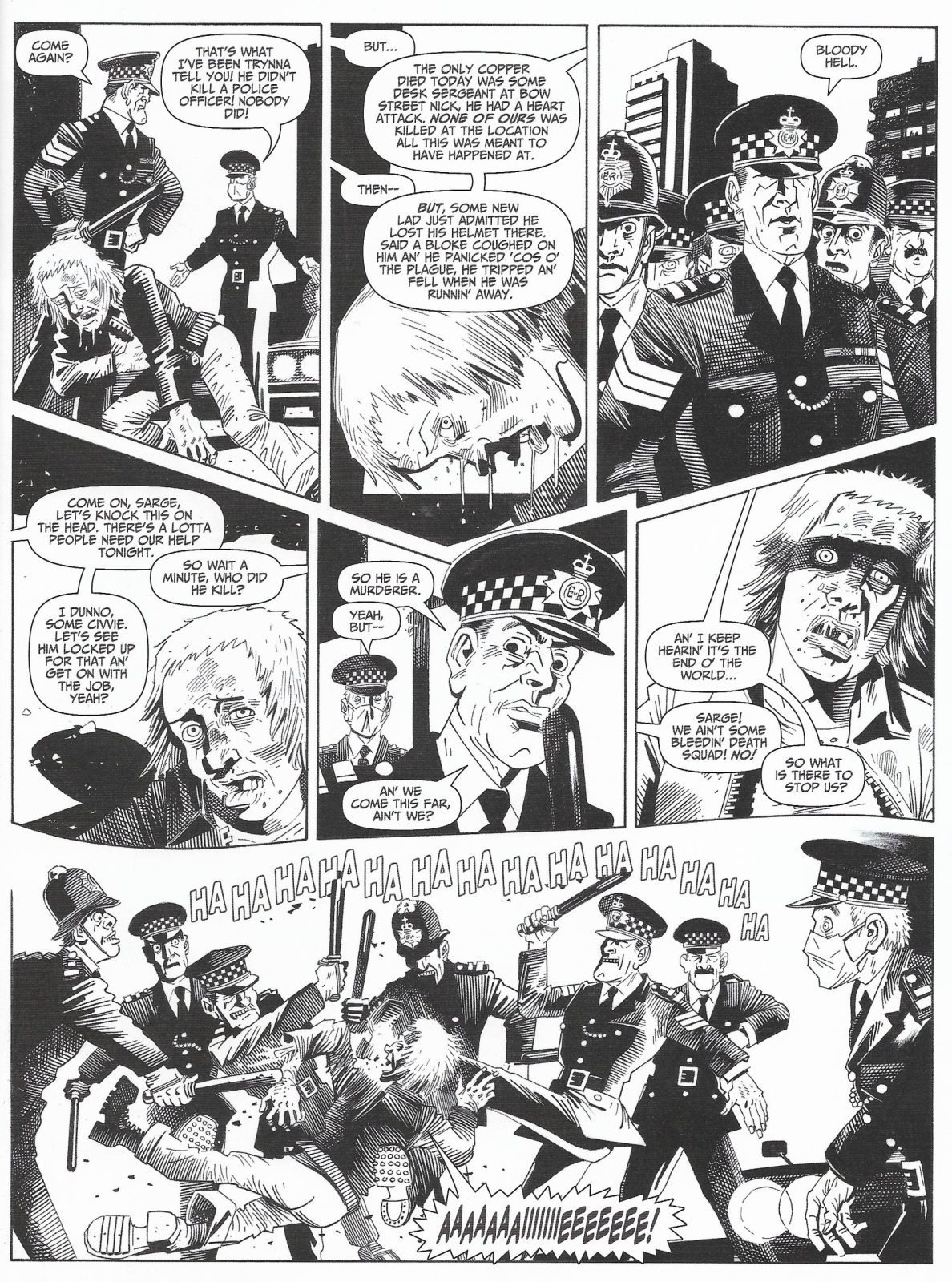

*Cosmic Comics 2nd Edition (Hibernia Comics, by arrangement with Rebellion)

A Kevin O'Neill miscellany, published before his death but including first-person commentary from the artist that adds to his legacy now. The best perspective on O'Neill's art is through things like the humor strip "Captain Klep" in Tornado, and the fact that, having put a graphic decapitation image on a fanzine cover for Dez Skinn in 1973, he reused the idea on a commercial magazine in 1976 and got into trouble long before the Comics Code Authority, or practically anyone else, knew who he was.

*Gutter Hunter #2 (self-published)

The movie streaming platform MUBI publishes a magazine of film criticism that costs £30 for two issues, presents material such as the travel diaries of Michelangelo Antonioni, and is so flamboyant in physical presentation that there are unboxing videos with people cooing on the soundtrack. Robin Bougie's Gutter Hunter is designed to mimic a comics fanzine–is a comics fanzine–and has the air of something you should smuggle into the house, with appreciations for things like the cover art of Amputee Love #1. One of these ventures in arts criticism has more honor than the other.

*The Legacy of Luther Arkwright (Jonathan Cape, forthcoming from Dark Horse Books)

Bryan Talbot's Luther Arkwright stories have appeared at widely spaced intervals over several decades and reflected the mood of the British Left at each moment in time. So the new one is deeply pessimistic and conflicted and suspicious of everything and not sure what to do about it.

*UFO Comic Anthology Vol. Two (Anderson Entertainment)

Being in practice 200-odd pages of art by John Burns (John M. Burns at the time) from the UK's TV Action/Countdown title circa 1972. Lowered into Britain's comics archive on ropes, the Gerry Anderson company emerges with one of its many licensed strips republished as a hefty hardback that manages not to put its contents on a pedestal, despite a price tag that could have bought a package holiday in 1972. Burns' figure work and choreography has remained almost unchanged and is instantly recognizable, even in the panels where he might have been drawing it on the bus - a rock-solid compliment.

* * *

John Kelly

This isn't so much a "Best of 2022" as a gathering of some brief thoughts about the past year.

In fact, it feels a little perverse to write a "Best of 2022" when it was a year in which I wrote an awful lot–far too much–about death. Justin Green died on April 23rd, which was a shock, even though I knew he was ill. To me, he was the greatest of the UG comic artists, the one whose work genuinely moved me the most. Then Simon Deitch on June 21st. Around that time I began hearing word that Diane Noomin was not doing well, which saddened me greatly. I loved her work and she had always been so nice to me the few times that we had met. When she died on September 1st, cruel was the word that came to mind. And then I heard the news that Aline Kominsky-Crumb was also sick, and it was impossible to believe that she would soon be next. But she was, and Aline died on November 29th.

At some point, between writing obituaries and memorial pieces about Diane and Aline, I received a copy of Drew Friedman's wonderful Maverix and Lunatix: Icons of Underground Comix (Fantagraphics) in which he delivers dignified portraits and brief bios of those four artists and many more (101 in total). I wrote extensively about the book–my favorite of Friedman's portrait series–here. You can also learn more about those same artists and their UG contemporaries in Brian Doherty's history of the time, Dirty Pictures: How an Underground Network of Nerds, Feminists, Misfits, Geniuses, Bikers, Potheads, Printers, Intellectuals, and Art School Rebels Revolutionized Art and Invented Comix (Abrams Books). My thoughts about that book–and my conversations with the author–can be found here.

And while much of my comics-related reading consisted of work by and about those I was writing obituaries for and compiling tributes about, not all of it was. My favorite book of the year, comics or otherwise, remains Jim Woodring's masterful One Beautiful Spring Spring Day (Fantagraphics), which I gushed–and asked Jim a million questions–about in this longish piece.

By far, the heaviest book(s) I received this year was Love and Rockets: The First Fifty (Fantagraphics), an ultra-handsome boxed set which weighs just under 30 pounds. It has been a joy to go back and re-read these stories in chronological order in the way I first discovered them. I haven't even come close to getting through this gift, but I know it will bring pleasure for many more years.

My biggest surprise of the year, by far, was Norwegian cartoonist Jason's Upside Dawn (Fantagraphics), which finds him working at his sharpest, cleanest and most Surreal. I greatly enjoyed these stories and maybe will write about them down the road.

A few other things that I liked very much in 2022 include:

Joseph Smith and the Mormons (Abrams Books) by Noah Van Sciver

Who Will Make the Pancakes (Fantagraphics) by Megan Kelso

Clutter: A Scatterbrained Sexual Assault Memoir (Fieldmouse Press) by Ariel Bordeaux

Ed Piskor's continuing Red Room series (Fantagraphics)

The (thankfully) ongoing existence of the Bubbles zine by Brian Baynes.

And while it won't be released for a while, I did get a chance to read Kayla E.'s extraordinary and painful collection, Precious Rubbish (Fantagraphics), which is sure to top many "Best of" lists when collected in 2024.

* * *

Sally Madden

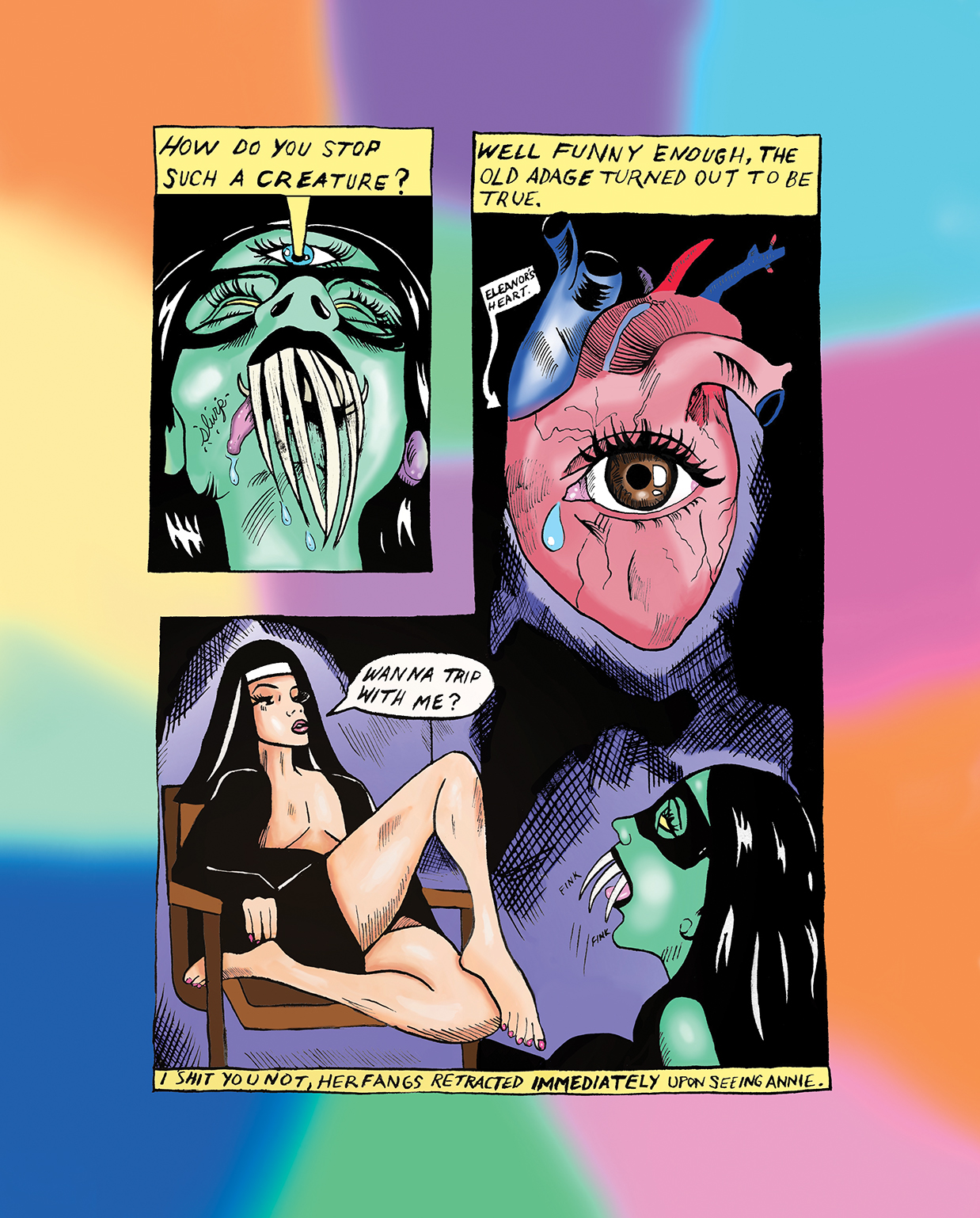

Acid Nun by Corinne Halbert (Silver Sprocket, 128 pages, color): A psychedelic, erotic and violent descent into Halbert’s id with Eleanor (a she-devil with retractable fangs), Annie (our beloved nun) and Baphomet. While exploring some wild trauma and grief, the tone of this book gratifyingly remains fun and energetic. Perfectly satisfies fans of the occult, tarot, and tits.

The Archway by Emma Jon-Michael Frank & Patrick Kyle (self-published, 102 pages, black and white): The story of absurd happenings on either side of a wall as a girl and two thieves struggle with their own separate worries and emotional voyages. It’s silly, sweet and heartbreaking, and despite the unusual process for the book (both artists working separately on what became facing pages) really hangs together as a joy to look at. I’d love to see more collaborative projects like this from other artists, it’s nice.

Dear, (A Superhero Comic Book) by Ina Parsons (self-published, 6 pages, color): Parson’s series of Superhero Comic Books (there’s at least 5 at the time of this writing) read like funny clues for a sad mystery you will never solve. The books are excruciatingly assembled cardstock on little cardboard planks, tiny and irresistible, not overdone, just worthy of the work inside.

The Devil’s Grin #2 by Alex Graham (self-published, 62 pages, black & white): Hail Satan for Alex Graham, the choice to not only have the issues of this comic double the length of your average publication, but also features a recap of #1 on the inside cover: life-saving. We continue our journey with Robert, living the lousy unkempt life of a poet; stories made of paranoia, hallucinations and our dicey relationships with the other people in the apartment building. Graham definitely adds to the roster of cartoonists resurrecting the legacy of American underground comics, I was such an idiot to think it had gone away.

Fondant #3 by J. Webster Sharp (self-published, 24 pages, black & white): While you may try to avoid eye contact with Sharp’s unnerving, grotesque, decadent drawings - the pages will look back at you, there is no escape. These silent comics have an insanely high level of draftsmanship and look as if they were a pleasure to draw; Sharp remains a heart-stopping master of texture. Plenty of body modification and exciting fashion lies within these pages that, I cannot begin to stress, are not for everyone.

Give My Best to Your Kind, Part One: I’m Sympathetic to Your Situation, Friend! by Frances Cordelia Beaver (self-published, 109 pages, black & white): The story of a creature declaring itself the first human; other animals feel a bit skeptical. Beaver’s characters remain as adorable as any Powerpuff Girl (this is the follow-up to her lovable debut graphic novel, On a Cute One), revealing mundane, amusing and painful moments, always with a tender touch. The illustrations are exclusively in a Prismacolor Ebony pencil that Beaver is working for every ounce of mark-making capability: smudging, smearing, shading. There’s a sequence where the creature lies down in the shallows and pulls the ocean water over themselves like a blanket, my eyes are welling up with tears just thinking of it.

Heaven #3 by Katie Skelly (self-published, 12 pages, color): This ongoing story of teen girls and a haunted strip club really allows Skelly to make the sexy, stupid, over-the-top action I know she’s capable of. This reads like a drive-in movie you’re not sure you should be watching, but you get more popcorn anyway. The closing sequence of this issue makes me sick.