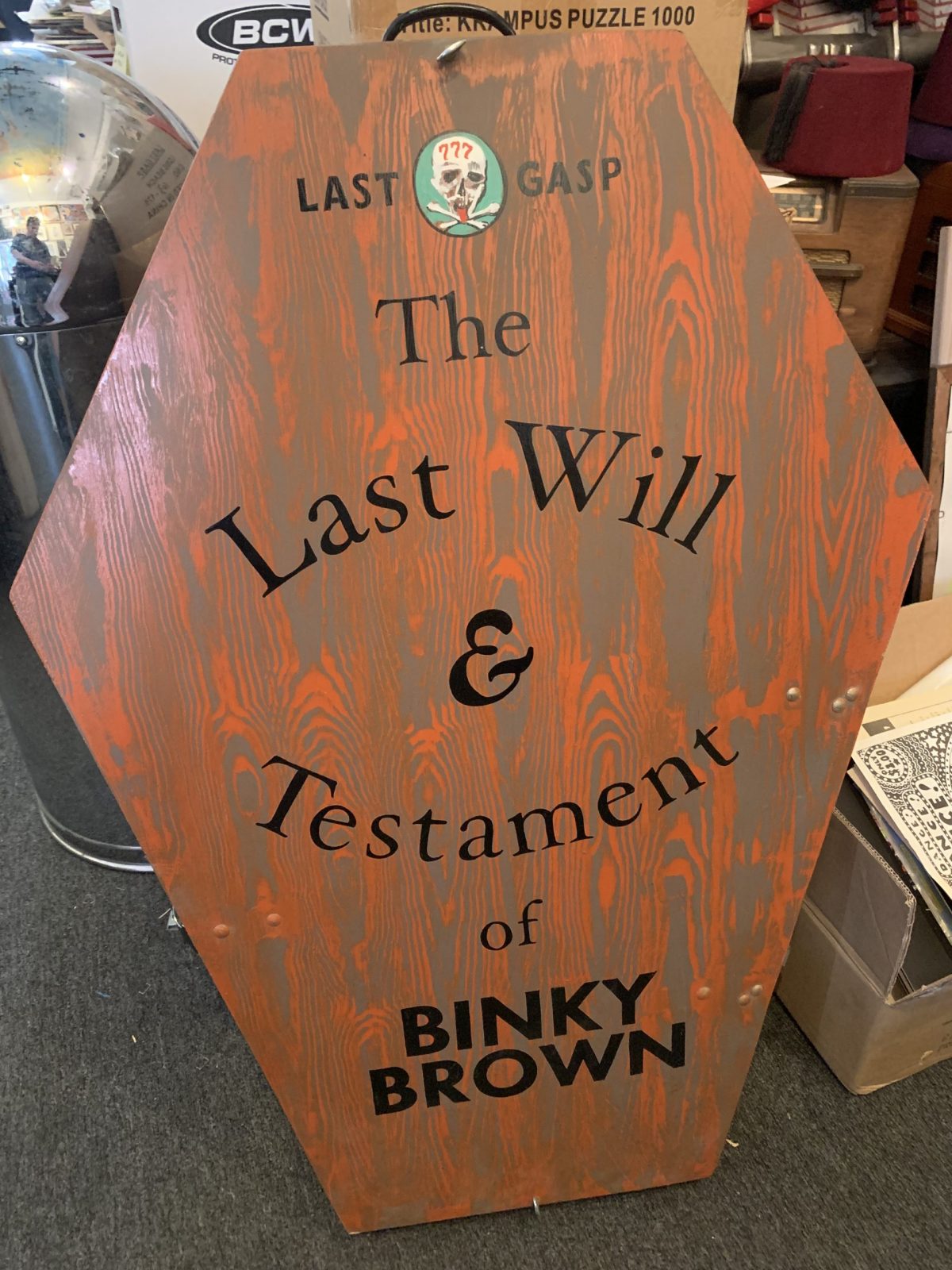

Justin Green was a groundbreaking cartoonist whose work gave birth to both the autobiographical genre and the minicomic format, as well as a masterful sign painter and all-around complicated man whose battle with his demons was most famously captured in his 1972 epic Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary (Last Gasp). He died on April 23 at Hospice of Cincinnati after battling colon cancer, according to his wife, the cartoonist Carol Tyler. A full obituary by longtime friend and comics historian Patrick Rosenkranz ran in The Comics Journal and can be found here.

Viewed by many historians as being the first true example of autobiographical confessional work in the comics medium, Binky Brown explores Green's youthful struggle with the Roman Catholic Church and his undiagnosed (and yet to be termed) obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). The book had a profound and lasting impact on his contemporaries, including Aline Kominsky-Crumb, Robert Crumb and Art Spiegelman, as well as later generations of cartoonists (whether they were aware of it or not). Spiegelman has said that without Binky Brown his Pulitzer Prize-winning Maus series would not have been possible. Spiegelman told The New York Times that Green "was coming from another planet. He was reporting from something no one was seeing. Out of a group of idiosyncratic people, he was the most idiosyncratic. He was so interior that he made comics grow up."

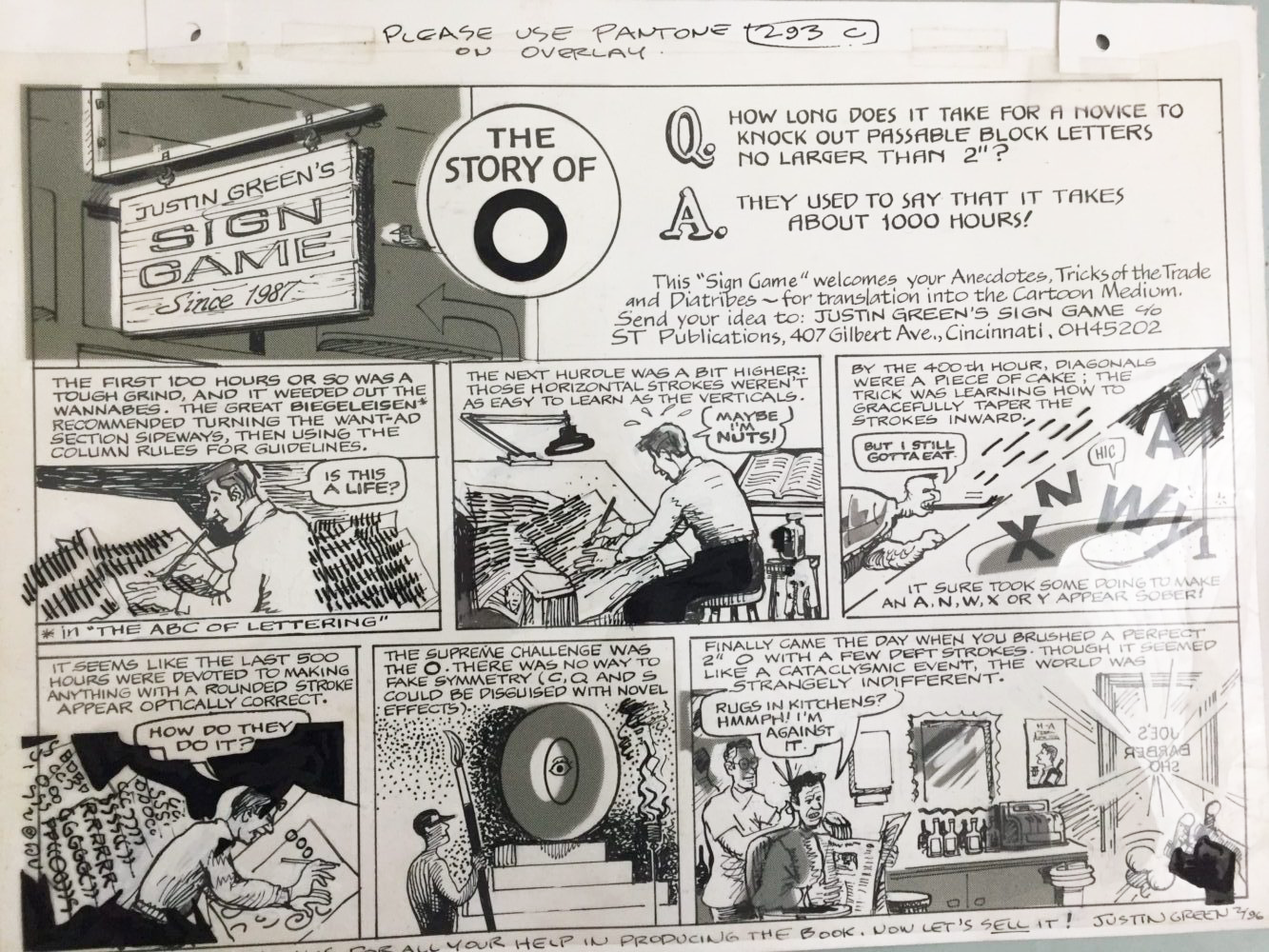

In addition to his work in comics, Green was also a professional sign painter; from 1986 to 2006, he contributed his "Justin Green's Sign Game" comic strip to Signs of the Times magazine, samples from which were collected in his influential book Sign Game (Last Gasp, 1995).

"Justin Green was an anachronism; a throwback to the 'mahl-men' muralists and ladder-ridin' barn-painters of days past," says Jeff Russ, content studio manager of Signs of the Times' parent company SmartWork Media and a longtime friend of Green. "With his monthly 'Sign Game' cartoon, Justin chronicled witty and insightful aspects of what it meant to sling signs. With his passing, the sign industry has lost a keen observer of its history, its timeless frustrations, and its capacity for humor."

In order to more fully give a picture of Justin's life and legacy, I asked a number of people–close friends, loved ones, contemporaries and collaborators, editors and artists inspired by his work–to share some brief thoughts and memories about him. At time of press, tributes were still coming in and an expanded version of this memorial will be collected into a printed edition that will be available in time for the opening of an ambitious retrospective of his career work to be held at his daughter Julia Green's Design Collective gallery in Cincinatti, OH, in early October, 2022. Along with countless never-before-seen examples of his work provided by his family, the exhibit will also put on display the complete original art from Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary. Any funds raised from the sale of the printed memorial will be used to help preserve and archive Green's work. More information about the exhibit, and a private memorial service for Justin, can be found at the end of this article, with updates to appear here.

— John Kelly

* * *

(cartoonist/wife)

I fell in love with Justin the day I first read his work. I felt an immediate kinship, having grown up Catholic in Chicago in the '50s. Instantly, I deeply understood the soul of this mad genius from the Midwest. Eventually, I got to meet him in person in San Francisco in the summer of 1982 — my god, it was as if the door to the rest of my life flung open. However... a permanent union seemed downright improbable, because we lived on different coasts and I had a boyfriend. But within two years, our sweet bi-coastal attraction took a miraculous upturn, as a heavenly host of angels swooped in and lifted us up to into those muscular clouds you see in Renaissance paintings. Pure ecstasy, with rays shooting out! But then, as we all know, such energy cannot be sustained. And so eventually, we leveled off onto an Ed Hopper type Cirrus plane, hovering evenly, although at times, we'd tilt toward the Medieval lake of fire below us, where pitchfork wielding demons relished the opportunity to poke at us.

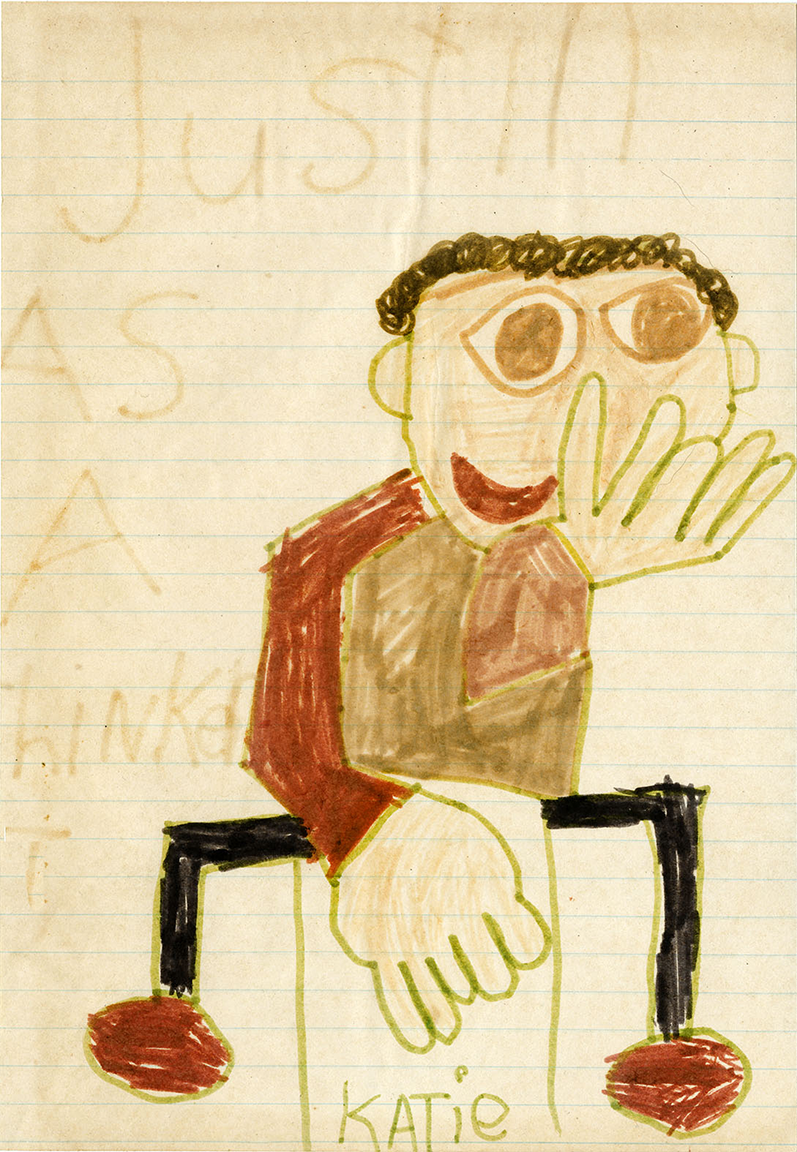

Justin Considine Green was certainly one-of-a-kind. An unconventional individual. Eccentric. Tormented. Guarded his privacy. Always working from his own angle. Always bringing a twist to every moment. The Justin Way made everything a little more difficult, but ultimately more interesting, and beautiful, which was absolutely necessary. He bent my mind, and I needed that. I became stronger and sharper because of him. His solution to my emotional outbursts was simple: "Just do your work." And so I did. He was kind and helpful when my parents were at their end of their lives. Plus, he was a terrific Daddy to two daughters who adore him.

Along with cartooning, and sign painting, Justin played guitar. Picked. Played bottleneck. Preferred the blues and old standards. Wrote many songs. His "Sign Painter Blues" is my favorite. Imagine this: meeting Justin Green for the first time, going to lunch, going over our shared roots over sandwiches, then going with him back to his wall job (the repaint of Tommy's Joynt). Then, on the way walking me home, swaggering into the guitar store, pulling a Martin acoustic off the display wall, and breaking into a perfectly Justin rendition of the Robert Johnson classic "Steady Rollin' Man". No wonder I was smitten!

When he turned 60, he challenged himself to learn "Elite Syncopations" by Scott Joplin on his 12 string. And once... well, here's a story. We went to pick up our teenager after a party out in the burbs. The garage band was done for the night, but the guitars and amps were still there. And so, this is something he never did before or since, he picked up the electric lead and, like a pro, blasted the cul-de-sac with "Crossroads," à la Clapton w/Cream. I had no idea he could play like that! Many times afterward, I begged him to repeat that performance, but alas.

And now I will speak to this, as many have asked: in the last few years of his life, Justin's anxieties and compulsions increased exponentially, driving him to set aside his pens and brushes to focus on finding the 'truth'. Add to that an aging OCD brain, plus cancer, plus the pandemic, and there you have it. I admit, I lost patience with his truth-quest. It was very hard on family and others. Apologies. But I never lost compassion for him or respect for him. Never lost sight of his genius. I don't think any of us did, or ever will. So in his memory, let's uphold the legacy of a generous, brilliant, talented, kind, caring, and loving friend to us all. You brought many gifts to our lives, Justin, and we are forever grateful.

xoxo Carol T.

* * *

(cartoonist)

I first met Justin in New York in 1969 or '70. We were both handing in pages for the East Village Other. I sensed a kindred spirit right away. I could see that Justin and I both came from non-comics backgrounds in the way we drew and wrote our stuff. Yes, we were the spawn of Harvey Kurtzman's Mad magazine, but we veered from that influence to find inspiration elsewhere. I felt then, as I do now, that Justin appeared fully formed as the cartoonist he was to be. I envied him for that. His perspective was closer to the art world, film, and writing than most of our comics contemporaries.

I remember Justin inviting me and my girlfriend to his place in New Jersey, a house that belonged to his aunt, where he was living temporarily. It was a Frank Lloyd Wright house, and it was full of cracks in the floors and walls. We all took peyote. It was not a good trip. Later, in the heady, early days of the San Francisco Underground, when we all felt we were revolutionizing comics–or at least aiming them at our fellow adults–three of us felt an even closer kinship; Justin Green, Art Spiegelman, and myself. Art even moved into Justin's Abbey Street apartment after Justin moved, which I visited often to hang out with both of them and talk about comics.

A few memories of that time–1971-74–pop up for me. I remember Justin, 15 or 20 pages into Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary in 1972, working at his drawing table one night when he asked me, in the formal voice he often used, would I agree to "finish the story" if he died before completing it? He was serious.

He showed me his breakdowns and notes. Taken aback, all I could do was say yes.

I think what that moment was really about was Justin's fear that what he was doing was so transgressive, he might be struck dead as his pen brought another panel to life. Justin lived around the corner from the Mission Dolores and he had to walk by it to get to the grocery store or the bus. Facing the sidewalk, in front of the Mission, was a large statue of the Virgin Mary. Justin told me had to run past it to avoid the rays which came from it, aimed at his penis.

This was not a metaphor for him. It was all too real. As he wrote at the end of Binky, he hoped doing the book would be an exorcism of sorts, freeing him from Catholic guilt. As he admitted to me many times over the years, that did not happen.

Justin seemed to derive no pleasure from creating comics. It was always hard for him. I'm sure that, and the fact that he never earned enough from the Underground publishers to pay his bills, kept him from going on with a comics career as the decades rolled by. Sign painting, at least, was not torture - and it did pay the bills. He put all his creative juices into his signs at that time. One window, for a "unisex" hair salon out in the Sunset District, sported "ideal" portraits of a man and a woman. Justin always asked customers if they'd like an image on their sign, at a higher price, in addition to the lettering. In this example, Justin painted a man who looked a lot like a pimp, complete with a floppy, feathered hat, and a woman who drew a close resemblance to Little Lulu. In another sign, an ice cream store in the Mission District, the owner wanted a little kid, happily eating an ice cream cone.

Justin painted his "bad boy" character Rowdy Noody, running so fast that his ice cream cone was blowing away in the wind. The great thing about Justin's signs popping up in various place in the city, was that they were done in oil-based paint and, thus, had a long life. They were there for years.

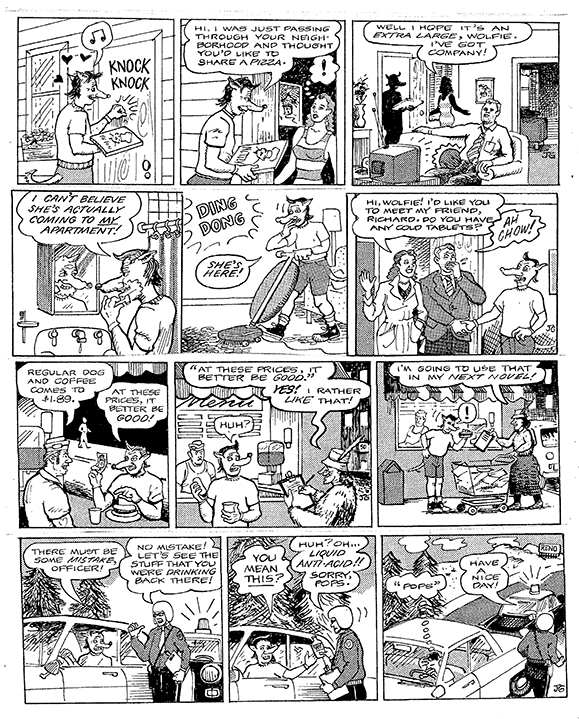

In the early '90s, I encouraged Justin to submit a daily strip idea to King Features. I figured if they ran with Zippy, there might be a shot at another Underground-derived strip, especially since King's comics editor then was Jay Kennedy, author of the original Underground Comix Price Guide and a big fan of Justin's. These Wolf Boy (above) strips were one attempt–there were a few others–but it was not to be. I guess King figured one weirdo (me) was enough for their befuddled salesmen.

* * *

(cartoonist, publisher via Kitchen Sink Press, founder of the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund)

Justin Green will always be associated before all else with Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary, which is understandable, but there was a lot more to him. He was an especially inventive cartoonist, tackling all manner of topics, generally with keen insight, or unusual perspective, and other times just for crude guffaws. Binky is a particularly important work, one that effectively started the now ubiquitous autobiographical comics genre. Even Will Eisner was influenced by that audacious and painfully honest comic.

Some of my favorite Justin comics are now quite obscure. In "Zen Time," a monk wastes his life repeating a misunderstood mantra. He did entertainingly instructive tips in a magazine for sign painters. A laugh-out-loud story in Sacred and Profane [Last Gasp, 1976] recounts his art school days. I love a silly Christmas card where Joseph in the manger proudly hands out cigars to the three wise men. He had a rough-edged and quirky drawing style that was off-putting for many, but it grew on others—certainly me—much like other idiosyncratic comix stylists of his generation. But that same non-commercial style and subject matter forced him in his later decades to paint signs, a reliable and honest living, even if we were deprived of new Binky dramas or crazed monks.

He lived in San Francisco during the height of underground comix, where I'd visit him periodically. His later years were with his wife Carol Tyler and their daughter Julia in southeastern Ohio, where I did not trek. But I got to spend a great summer in the mid-1970s with Justin when I lived on a former farm in central Wisconsin. He called me from the Bay Area to say he had a traumatic break-up with Nancy Griffith - Bill's sister. He said he needed to get "far away" and asked if I could use some company for a while. Not long before his call, my wife Irene had abandoned me to raise our daughters—an infant and toddler—alone, so I was half-crazy myself. And lonely.

Justin amateurishly cut his long hair to the nub in penance, and hopped on a Greyhound bus. He planned to hit Chicago, then north to Milwaukee and then to within forty minutes of my remote farm. But somewhere en route he got waylaid: a stranger offered him a glass of orange juice that was dosed with LSD or another mind-altering drug, and Justin next remembered being in the bathroom of the Philadelphia bus station, way past his Chicago connection, "banging his head against a wall." When I finally picked him up in Oshkosh he was bedraggled and forlorn, hair mangled, and eyes bloodshot.

He crashed briefly in my farmhouse guest room. He was welcome to stay indefinitely but Justin decided it would be best for our friendship and his work discipline if he rented a place near my Princeton location. He chose Green Lake, about ten minutes away. Green Lake, Wisconsin's oldest resort area, was infested with summer tourists, mostly wealthy Chicagoans, but it was an otherwise charming and picturesque location. He loved that the town sounded like it was named after him. Justin rented a room in a former Masonic lodge (a dusty stack of "secret rituals" came with the closet). He claimed his landlady would periodically go into his room and snoop, so while working on an erotic "Dog Boy and a Geisha" story for Young Lust he had to hide the originals between the mattress and box springs whenever he left.

Cartoonist Pete Poplaski and my younger brother James, who both lived on the complex (locals erroneously called it "the commune"), spent many evenings that summer with Justin and me shooting the shit over beers and weed. Justin and James sometimes played harmonica on the deck or around a campfire. Those few months in close proximity, each of us nursing broken hearts, but also brainstorming ideas and swapping laugh aloud stories, forged a bond that survived many subsequent years of seeing each other only intermittently.

After three months or so Justin left Wisconsin to head back to California. Shortly before he split, a terrible murder occurred in Green Lake: an elderly woman was bludgeoned to death—an unheard-of event in our placid region—and there was no obvious culprit. The Masonic lodge landlady tipped off the local police that she had an unsavory-looking tenant who had suspiciously left shortly after the crime. A police officer came to my Kitchen Sink office in "downtown" Princeton to see if Pete or I could amplify her finger pointing. Naturally we assured the officer that Justin was a peace-loving hippie who wouldn't harm a flea. There were no further inquiries. I don't think they ever solved the homicide.

From the early '70s into the 1980s I published Justin's work in various KSP comix anthologies, and the 5-part "We Fellow Traveleers" in the Marvel experimental magazine Comix Book. He contributed to my pin-back button line and even drew a baseball card [below] for one of my local softball team sets. He, Pete and I jammed on a Krupp Mail Order catalog cover, and he contributed a political cover for the Bugle-American, a weekly underground newspaper I co-founded. We engaged in old-fashioned, often rambling correspondence in that pre-digital era. Sometimes he would even send me gigantic folded letters, done no doubt while he was in his sign shop. We'd talk on the phone with some regularity.

Around the time I moved my publishing operation to Massachusetts in a mid-'90s merge with Tundra, our communication was waning. While there were periodic emails, the tight relationship we once enjoyed suffered from benign neglect. Then, several years ago, filmmaker John Kinhart, working on a documentary about Justin and Carol, contacted me about archival material. I loaned him 8mm footage I shot of Justin in the '70s, one at a party in Willy Murphy's apartment, and another when Justin and I visited Bob Armstrong, Aline Kominsky-Crumb, and others in Dixon, California. Seeing that old footage brought back warm memories, and Carol had privately alerted me that Justin was losing a battle with advanced colon cancer. He had ignored symptoms till it was too late to be cured. So, a couple of years ago I reached out to him via email.

There was no response till four months passed. Then he finally emailed, and briefly reminisced. Recalling his Wisconsin trip nearly five decades earlier, he said, "That was a pivotal Summer in my life." When I reminded him that he was briefly a murder suspect, his response was, "The landlady called me unsavory? Ouch!" But then a surprising shoe dropped. "Okay," he wrote, "there's another reason for my procrastination. I don't want to alienate yet another friend by sharing my political truth."

His political truth? Justin had fallen deeply down the 9/11 Truther rabbit hole. He was also a hardened anti-vaxxer and COVID anti-masker.

We exchanged several more emails. We debated without rancor but he was implacable about his "facts". I've always been science-based and so I asked for his "best evidence" re: his alternative 9/11 theories. He forwarded links to alleged experts, some of whom were transparent nut cases. I did research on some of the outlandish claims, naively thinking I might change his mind, but no logic or scientific evidence could cause him to doubt that a missile hit the Pentagon and our own government blew up the Twin Towers. I eventually gave up. We remained friends. As Justin put it, "Though I have had to sever connections with friends and peers over the touchy topic we are discussing, I would never willingly end our friendship over this matter." In fact, he wanted to continue debating, but I saw no point.

I still find it impossible to understand how an otherwise brilliant guy—a true genius cartoonist—could embrace crazy and easily debunked 9/11 conspiracy theories as well as anti-vax thinking. And, in truly self-destructive behavior, why did he refuse to seek medical attention till he was terminal?

Just two weeks before his demise Justin promised a blurb for a book I was finalizing. A week later he emailed to ask my phone number, which I quickly provided. But no call followed, no blurb, no goodbye. Though he was clearly very ill, I didn’t realize he was that close to the end. Rest in peace, my tormented friend.

* * *

(cartoonist)

He was a good guy; and brilliant. I liked him very much. He leaves behind him a very brilliant and talented wife. I am expecting great things yet from her. People, his friends, always said he was a nut job. I always tended to deny it. They were probably more right and I was probably more wrong. But remarks like that, about him, tended to annoy me. I considered them flip and "too easy". He was very talented. He was honorable, and he will be missed.

* * *

(cartoonist)

I met Justin in the early 1970s, not long after the debut of his comic book masterpiece featuring Binky Brown. Like so many other underground cartoonists at the time I was profoundly inspired by this seminal work. Justin was unique at the time for sharing his personal struggles with OCD and anxieties over Catholic guilt in such an artful way. I came up with my own autobiographical story a few years later in Arcade, the Comics Revue, although I didn't experience anything like the torment that Justin went through. It was while contributing stories for Arcade that I got to know Justin better and I found that he also played guitar. We both shared a love of listening to and performing the blues. I remember him jokingly admitting that he felt he was a bluesman. When we had the opportunity to play a few numbers together, Justin shared some of his unique songs that only he could have composed.

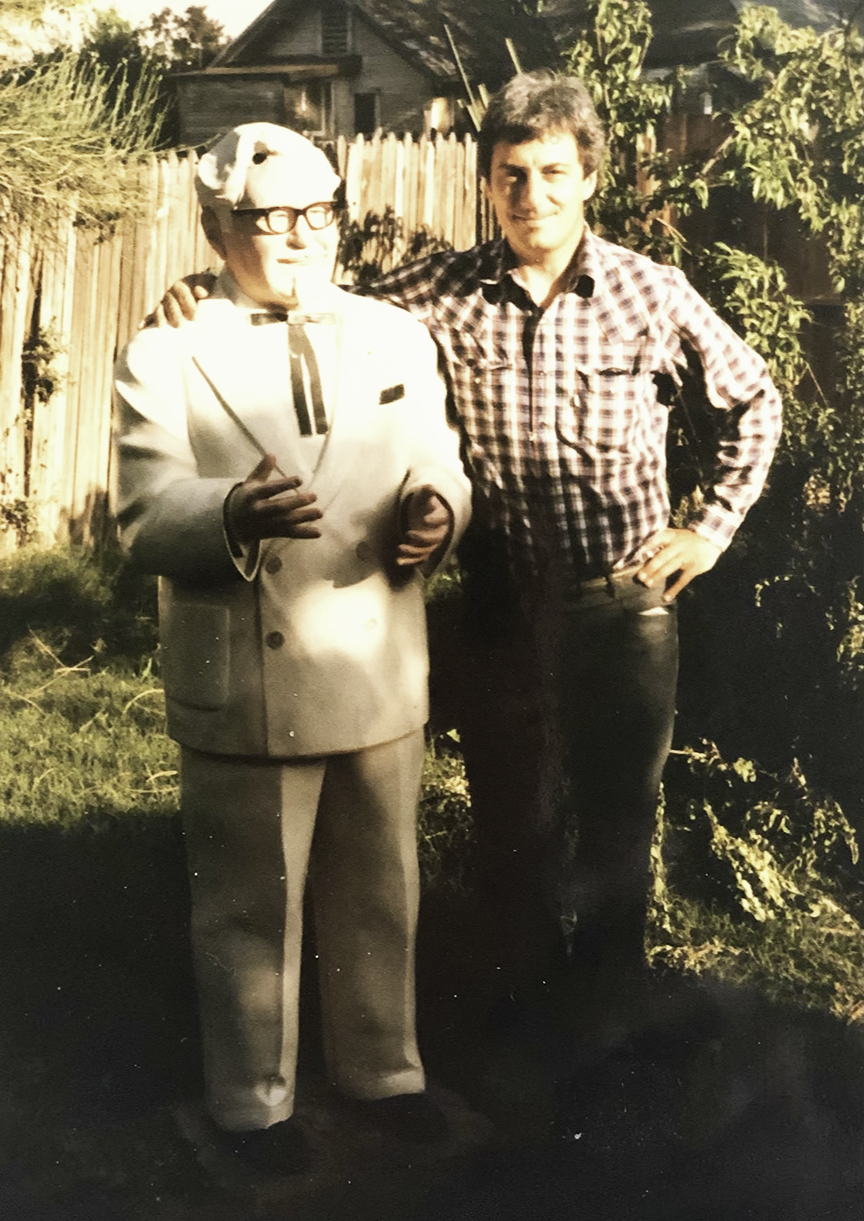

Justin was living in San Francisco, at the time an epicenter of underground comic culture, and I was living an hour or so away in the Sacramento Valley, so I didn't get as many chances to visit with him as I would have liked. But a few years later in the 1980s, he and his cartoonist wife Carol Tyler moved to Sacramento. It was around this time that Justin called me and asked if his friend, the Colonel, could come stay with me. I wasn't sure how to react to this request until he explained that it was a life sized statue of Colonel Sanders that he wanted me to take care of for a while since he lacked the space. Of course I welcomed the guest along with all of his finger-lickin' goodness. This was around the time that Justin drew a hilarious/disturbing portrait of the Colonel slaughtering chickens in a bloody chaotic mess. Continuing with this theme; a few years later, Justin, Carol, and their daughter Julia showed up at one of the Halloween costume parties I used to throw, all dressed as Colonel Sanders carrying buckets of fried chicken.

Moving ahead to the early 1990s, both Justin and I contributed work for Pulse!, which was a music culture magazine published by Tower Records, which was headquartered in West Sacramento. I wrote articles, did illustrations and comic stories, and Justin contributed a fine series -"Musical Legends of America," which highlighted the lives of a variety of performers and cultural icons. We would occasionally get together to play our guitars and hang out. It was at one of these get togethers that I told him about a frustrating experience that I had just gone through. I had been asked by a music promoter friend to put together a small musical group as an opening act for Leon Redbone, who was booked to perform at the Varsity Theatre in downtown Davis, CA. I enthusiastically contacted a few musician friends and we rehearsed a set's worth of musical offerings from the 1920s and '30s on vintage acoustic instruments. We and the promoter of the event agreed that it would be the perfect compliment to the type of material that Leon Redbone played. However, on the night of the big performance, the promoter, in a total panic, told us we couldn’t perform because he failed to read part of Redbone's contract that stipulated that his opening act could not be musical. I tried to meet with Leon Redbone to prove that our group would be in keeping with with the type of material that he played, but he refused to talk with me and instead hid out in his band bus until showtime. Meanwhile, a deal was struck with the promoter, who was desperate to have some sort of opening act. He asked if I could play solo musical saw for a 45-minute set because somehow Redbone's manager figured this wouldn't be "musical". It took a lot of coercing and several beers to get me out on the stage alone with my saw since I had never done anything like this before. Fortunately my efforts were well received by the audience, but it was a trial by fire.

Justin listened to this story with keen interest and, in a later issue of Pulse!, his "Musical Legends of America" featured me and my experience which he titled "Looking For Leon". Justin, with a touch of dramatic license, showed me angrily chasing after Redbone's band bus with my saw in hand. I had been immortalized by Justin Green in a story. What an honor!

While Justin was living in Sacramento we would also talk about sign painting, which I would occasionally do myself. Since he was relying more and more on sign work than cartooning at the time, he had a lot of tips of the trade to share. When Justin and Carol moved to Cincinnati it became more difficult to stay in touch. I had hoped to go visit him there, but life's demands got in the way of my plans. We would occasionally exchange emails or "like" each other's work on Facebook or Instagram until fairly recently, so it came as a huge shock to learn that he had been battling cancer and had died. (Sigh!)

Unique is only one word to describe Justin Green. Besides being a truly original storyteller, cartoonist, songwriter, master sign painter, and all around great guy, he was also a bluesman.

I’ll sure miss him.

* * *

(cartoonist)

I had the honor of meeting Justin Green a few times over the years at various comics events (once he and his [all-time great cartoonist] wife, Carol brought pizza to a group signing event I was doing in Sacramento - as kind a gesture of support as I can recall in this hard-boiled cartooning life), and even though he radiated an innate kindness and a fatherly Zenmaster's calm, I found myself far too intimidated and overwhelmed in his presence to do more than mumble a few uninspired questions about Speedball nibs and slink off. He seemed to possess (and certainly displayed in his comics) an extra level of awareness, an ability to see things on a micro (macro?) scale that were invisible to the rest of us. I wish I had just steeled myself against what I perceived as the unbearable scrutiny of an elevated consciousness and told him plainly how much his work meant to me. I think about his perfect idiosyncratic dialogue and his unmatched display lettering, among many other things, on a daily basis. I'd tell him that Sign Game is the best book I've ever read about what it's like to be a working artist, and how lucky we all were to be able to see the world—both our outer shared space, and his own tormented inner existence—through his eyes.

* * *

(cartoonist)

In early 1972 there were hundreds of cartoonists producing underground comics, but there were very few indisputable game-changing greats. Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary appeared that year and conspicuously added one more. Some, including me, would say Justin Green was the finest of all the undergrounders.

As has often been noted, BBMtHVM was the first major autobiographical American comic, but it was much more than that. Justin opened thousands of jaded, red, adolescent eyes to the reality that comics could embrace great depth and psychological incisiveness without sacrificing raunchiness. I knew a number people who despised all the ug comix they saw except for BBMtVM. It was the most adult of the ADULTS ONLY funnybooks.

Personally I think Justin was a mystic. All his work is otherworldly; pointedly so in the cases of BBMtHVM, the overtly metaphysical "We Fellow Traveleers" and numerous punchy short pieces like "Zen Time". It seemed to me that his primary mission in life was to explore, analyze and understand what was happening to him, and to convey his perceptions to the world, which he did with the forced exhibitionism of an introvert.

Justin knew that his drawing style was perceived by many as being crude, which must have irritated him. But he also knew that anyone with a gram of perception came to realize that his work was absolutely stellar. His drawing was as expressive as his wonderful hand-lettering and in fact bore a stylistic resemblance to it: strong, direct and infused with his personality. There's no doubt that Justin, with his phenomenal inner eye and hand-control, could have drawn in a slicker style if he'd wanted to, but what a loss that would have been!

He concocted an unprecedented approach to comics-making. As he himself put it, he spilled his guts out. Others tailored and told their truths; Justin was groundbreakingly honest. He participated in that golden age of taboo-shattering comics, but went about it in a singularly earnest and intelligent way. His transgressions were subtle, profound and uniquely funny.

He didn't make it look easy. I think Justin considered being a craftsperson a sort of sacred trust and that that to be worthy of the title was to commit to more than honing your skills at the drawing board; it meant embracing a guild-like policy of integrity, dependability and humility that conferred honor upon the profession. He felt an obligation to deliver the goods in every way.

Some time in the early '80s I found an unsigned original drawing by him (above) on the floor of a comics shop; people were literally stepping on it. I picked it up, realized what it was and took it to the cashier who said, "Oh yeah, that thing," and sold it to me for $10. After a few months I worked up the nerve to contact Justin and ask him to sign it for me.

He was nice as pie. He knew my work and to my astonishment suggested we trade originals. I said I would be very glad to, and that I'd give him three or four of my pages for one of his.

He said, "No sir. We trade even-steven." That, I found out, was his character in a nutshell.

Over the years we corresponded extensively, visited each other, exchanged art and artifacts. He was an exemplar to me, a model of artistic and personal integrity and of grace under stress.

And the stress was considerable. As he himself told the world, Justin had to battle psychic forces that made his life very difficult. He experienced terrible sorrows, struggles and sacrifices, and had to work hard to maintain his sanity. But whatever he was going through, I never knew him to be anything but kind, present, lucid, eloquent and generous whenever we wrote or spoke to each other.

During his last year, when he was ill, worried and in furious despair over the world situation, he made a point of reaching out to me to make sure our friendship was solid. That also was his character in a nutshell.

* * *

(publisher via Last Gasp)

"Justin Green is my all-time favorite for being perhaps the most intellectual cartoonist. He had all those strange ideas about the rays coming out of Mission Dolores and hitting him in a certain way. He was serious about this ray stuff, but his cartooning was so good! It really captured the depths of neurosis a human can overcome.

"Our agreement was that I would buy him groceries and pay his rent if he would continue working on his story. If he finished it - great, if he didn't - fine. It was just a gamble, but it paid off!

"In our later book, The Binky Brown Sampler [1995], Art Spiegelman, who won the only Pulitzer Prize for cartooning, reports in his foreword that he would never have started to do the autobiographical story of his family (in the graphic novel, Maus) unless Justin had done it first. And Robert Crumb said the same thing."

— Interviewed by Gayle Nelson, 1999

* * *

(comics historian)

In 1972 when I began corresponding with Justin Green, he told me about his upcoming new comic book. "You can probably tell by looking at my stuff that I am a big fan of conscious control," he wrote, "the main reason is that I believe there should be a constant dialogue going between one's conscious attitude about life and their work. Since I began cartooning in '67 I have been able to deal with red-hot neurotic conflicts within me that I would have been victimizing myself with for the rest of my life, chances are. Most of these are in Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary."

A solo comic book was a mark of distinction in the early underground comix movement. It showed that a cartoonist had what it took to produce a solid 36 pages all by himself. Green had cut his chops in several anthology titles, including Yellow Dog, Gothic Blimp Works, and Bijou Funnies, but Binky Brown was a declaration that he could stand alone.

A month later he sent me several copies and asked me to spread them around. He said he'd put nearly a year into this project but still wasn't confident about whether it would be accepted. I recognized its originality and visual impact right away, and I wasn't alone in my assessment that Green had just added a new genre to the comic medium - autobiography.

Binky's success followed Green for the rest of his life, sometimes overshadowing his other myriad accomplishments as an artist, and often making him tired of hearing about it, but he acknowledged his own inspirations for this work in James Joyce's Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, and Phillip Roth's Portnoy's Complaint and James T. Farrell's Studs Lonigan Trilogy. "Autobiography was a fait accompli, a low fruit ripe for the plucking," he insisted. "Ironically, I have to give myself the one accolade I truly deserve: that Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary anticipated the groundswell in literature about obsessive compulsive disorder by almost two decades."

* * *

(cartoonist)

Justin was my next door neighbor on Abbey Street in San Francisco. So long ago. I remember seeing Binky Brown art on his drawing board and him playing a 12-string guitar. He was such a serious guy. It was like he was scowling a lot, but I think he was just doing what they call "knitting the brow" as he considered all the stupid stuff we were saying.

* * *

Drew Friedman

(cartoonist)

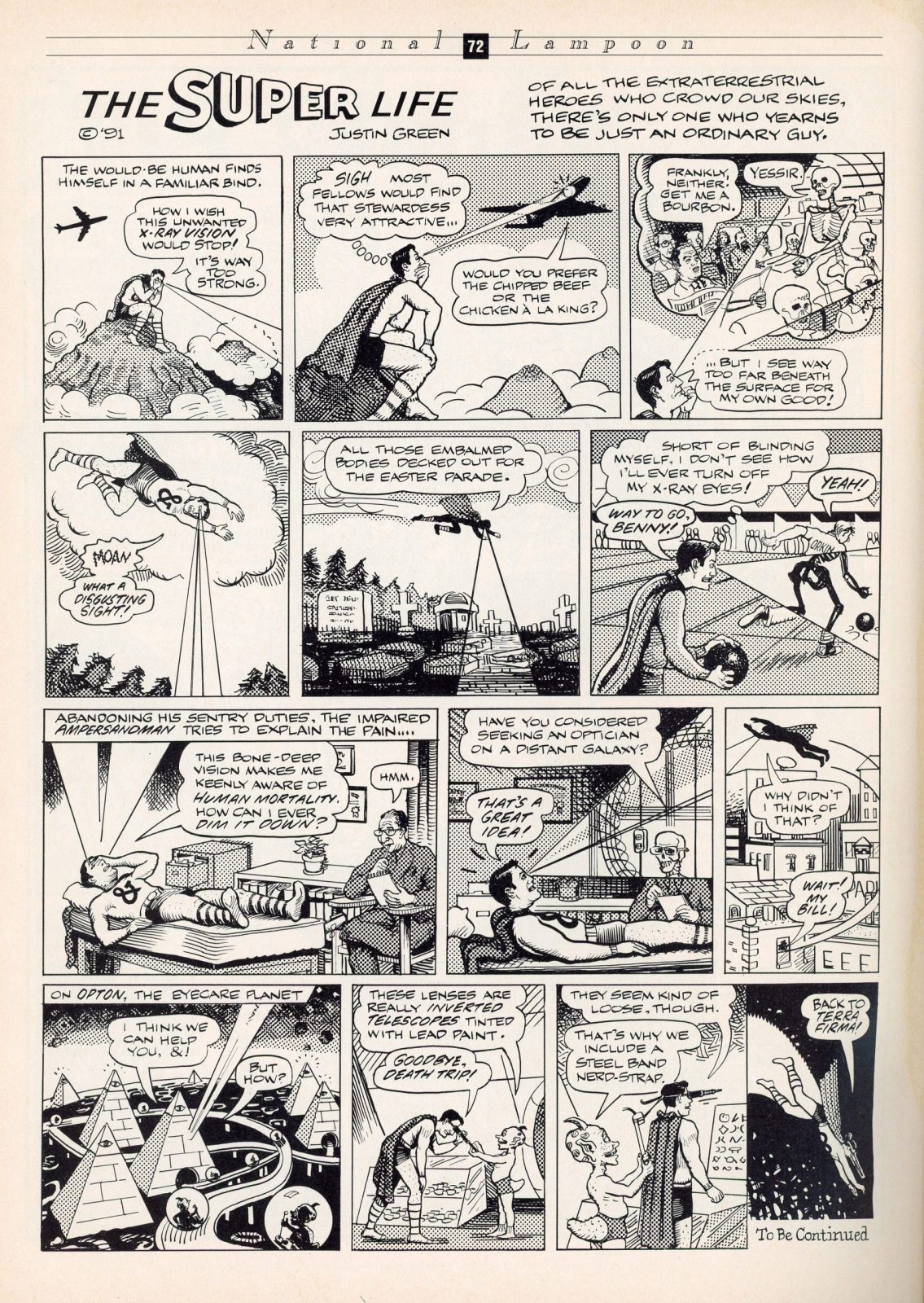

In late 1990, I was hired to revamp the "Funnies" section of National Lampoon magazine. My friend George Barkin (brother of actress Ellen Barkin) had just become the Lampoon's new editor-in-chief in their latest attempt to revive the floundering humor publication which had been going increasingly downhill for more than a decade, to drop the lame sex jokes, and to try to compete with the hugely popular Spy magazine. George asked me to contribute a monthly comic page, become the new comics editor, and invite some of my hip cartoonist colleagues to help accelerate the "Funnies" section by infusing it with a Raw/Weirdo type vibe. I invited my old SVA pals Mark Newgarden and Kaz to take part, and also Doug Allen (Steven), Daniel Clowes (who was writing and drawing Eightball at the time), and an unknown cartoonist named Chris Ware who was still attending college. My wife Kathy had alerted me to Ware's already outstanding work from among the piles of cartoon submissions that she was sifting through at home on my behalf. All five artists became regulars in the new section with Newgarden creating the new "Funnies" logo.

In addition, I reached out to several underground comix icons, among them R. Crumb and Justin Green. Crumb told me he was just too busy (my guess was he was reluctant to do work for the Lampoon, which I certainly couldn't blame him for), but Green wrote back to say he was excited by the prospect. As a huge fan of Justin's work I was thrilled. His painfully confessional 1972 Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary is a masterpiece of autobiographical comics, and I adored all of his additional underground comix work, especially his comics for Young Lust. I totally concur with Crumb on Justin Green: "I love every stroke of his nervous pen, every tortured scratch he ever scrawled!"

I phoned Justin at his home in Sacramento and he told me he had been enjoying my work and was flattered to be asked to contribute to the Lampoon. When I mentioned that the page rate was $600, he took a long pause, and without a trace of sarcasm responded: "Well, I guess my ship has come in." I told him he could create anything he'd like for the "Funnies" section, I didn't want to hinder him or steer him in any direction (or any of the other artists), aside from the single caveat that the comic strip be funny, or what he perceived as funny. Justin got right to work and soon mailed in "The Super Life," featuring a superhero called "Ampersandman" who yearns to just be an ordinary guy but must follow his superhero destiny. Justin Green was perhaps the least likely cartoonist I could think of to draw a superhero comic but I whole-heartedly encouraged him and "The Super Life" debuted in the May 1991 issue, continuing over the next six months. But, inevitably, all the artists I had hired would be dumped, as was editor-in-chief Barkin, his fellow editor minions, and finally me. The die had been cast long before; Lampoon's sales had continued to slide, it would soon change ownership, close up shop in New York, move to LA, and continue its slow, steady downward slide into oblivion.

Justin and I would become pen-pals for a few years. At one point he wrote to say that he felt "The Super Life" "never flowed, it's taken me several years to get back in stride," and in retrospect that he felt he should have made the main character an old Jew named "Uncle Sol". In 1993 we discussed my indifference to computers: "Drew, I understand your reluctance to let the computer into your life, and you could certainly get by without one, but it's a great time saver and ass-coverer." His hesitation to continue sign painting: "Just thought I'd let you know, I don’t do signs anymore. My backyard is a still-life of paint cans and solvents, covered with leaves and cobwebs," and his desire to move back east: "Every time I go back east, I want to relocate there. The sad truth is I don't have the five grand to pull it off. I may resort to doing florescent display lettering; everything else is done by computer now." He would periodically compliment my latest work, at one point writing "an old hatcher salutes a boss stippler."

Justin and I would finally meet at a 1995 New York bookstore signing for the Raw books artist jam The Narrative Corpse (I seem to remember that he was staying at Art Spiegelman's loft during his visit). He was extremely low-key, not a trace of ego, confessing to me at one point during the signing that one of his big toes had turned dark-purplish: "Drew, I've begun the process of dying." Sadly, 27 years later, I guess he was correct.

* * *

(curator, editor, publisher via PictureBox, Inc.)

Many artists are best eulogized with their own words. Years ago Justin Green wrote to me explaining his "frottage technique" for composing panels: "The primary function of rubbing, splattering, blotting, etc., is that it serves as a hallucinatory ground. I think Leonard Da Vinci mentions starting into cracks and tree trunks for shapes that would spark inventive landscapes. It is a timeless artists' crutch. I call it 'poor-man's marijuana,' now that the stuff is 300 an oz. It's a Rorschach-like way of fishing images out of nothingness. This is not appropriate for every panel, of course. Sometimes what is called for is sheer mechanical/conventional drawing."

Justin understood drawing better than most, and also cartooning. Spain's Trashman, too, saw much in the cracks, and of course every cartoonist needs a quick trick. Not a crutch, which implies moral judgement on Justin himself, but a tool for expediency's sake. To finish the panel/page/book. And of all the people I've interviewed about Robert Crumb, it was only Justin who went right to the nib, via a sports illustrator named Anthony Ravielli:

"Ravielli was a master of the scratch board technique—on par with any artists who ever wielded the carving nib. This is much closer to the medieval burin than the flexible steel nib. Though scratch board marks are often employed in the building of tone and seldom make use of a fluid line that changes in weight. Crumb's 'fine art' pieces are much more about tone building than expressive line—though certainly there is artistry in the compositions and the stand-alone lines that balance the large blocks of tone."

Who else would go so far to come back to a single point?

The way Justin thought about drawing, which he used to cartoon, is maybe my favorite: practical, mystical, funny, technical, precise, and with nods to history. And it comes directly from practice. He made a life of drawing about his interior life and the external life of sign-making. A brutal, tough, gorgeous business is sign painting, and one about communicating. In his comics, Justin communicated not through the clarity and geometry of signs and symbols, but through drawing that linked back to the 18th and 19th century modes more than anything contemporary. Line width, line weight, figure poses, usually in full figure. His mode is closer to Tiepolo than EC, occupying a curious place in cartooning history. Nothing he did was really "correct" by contemporary standards of minimal, flow-through cartooning.

Reading Green demands slowing down, processing as he puts it, the lines and tone. That undergirds the narrative, which itself is always constructed to resolve in a mini-revelation. A point of knowledge.

His passing is a sad reminder of his brilliance, which I hope will now be seen anew - he spoke of a collection of his short stories, for which, I told him, I would do just about anything. Perhaps a new Binky Brown edition, scanned from the original art but printed as line art? And most of all I think of all the lost knowledge, the lost stories of his life and our shared cultures. He deserved more.

Before Justin died I was in San Francisco. Jay Kinney walked me over to see the apartment in which Justin drew Binky, one of the towering achievements in 20th century American art. I never knew it until I was right there on that tiny lane, but Justin could see the Madonna from his window, there at the Mission Dolores. She beckoned to him, across the wall, down the pavement, as if transmitting to him his own personal frottage from which he made art that illuminated and entrapped him.

Thank you, Justin. Sending love to Carol, Julia and his family far and wide.

* * *

(cartoonist)

In one illustrated lecture for my cartooning students, I swipe through slides of my own swiping. I copied drawings by Peter Arno to learn how to compose gag cartoons. The adaptation of City of Glass, that I co-created with David Mazzucchelli, would not exist as it does without my studied pilfering of Harvey Kurtzman's perfection of the nine-panel grid. Economy of line: Ernie Bushmiller. Form follows function: Winsor McCay.

Finally, I get around to a cartoonist to whom many cartoonists owe a great debt as he practically created the modern comics memoir, combining the metaphysical with the down to earth to explore personal history using comics.

I swiped from Justin Green. For honesty.

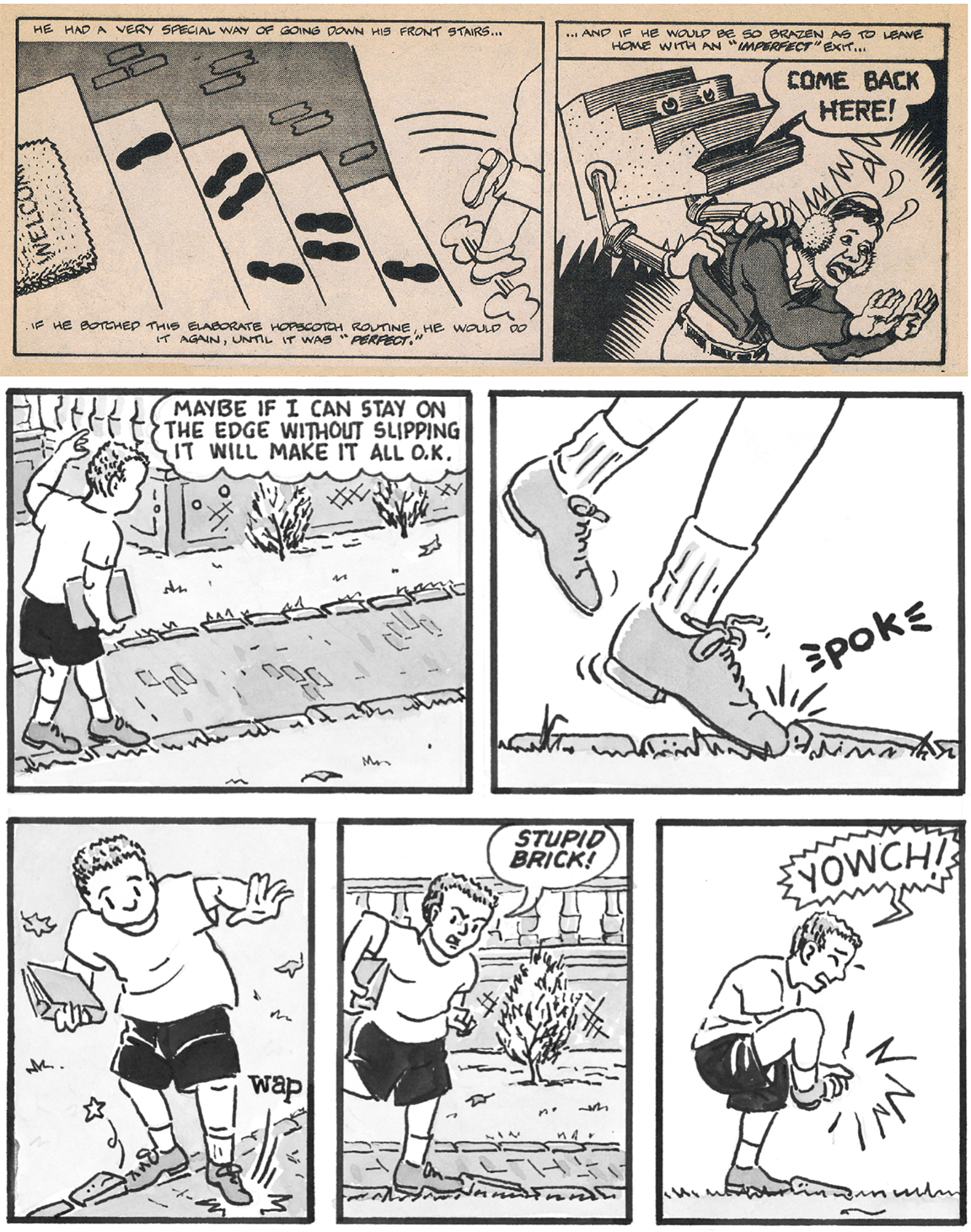

When I began creating the comics/prose memoir about growing up with an older brother with autism and developmental disabilities, The Ride Together, created with my sister, Judy, I turned to Green for inspiration, determined to be as honest.

Reading Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary was the first time I saw a comic depicting the neutralizing of fate through private rituals. This is something that I did as a child trying to make sense of the world and somehow exert control over the confusion. It was behavior that I knew was weird and never shared.

Below is an example in the top tier by Justin Green depicting the use of ritual to thwart fate followed by two tiers from The Ride Together of little Paul trying to employ a similar strategy. Most likely, I would not have gone down that road, publicly sharing such private behavior, had not Justin Green paved the way.

As an adult drawing a comic about my younger self, it was natural to dust off Binky Brown and swipe from the Master.

When we were interviewed on NPR about The Ride Together, the interviewer asked us if everything in the book actually happened. My sister, Judy, replied "No… but it's all true."

* * *

(cartoonist)

I didn't know Justin Green well. We only met once. One meeting doesn't count for much when you are getting older. Polite chat. Pleasantries exchanged. Every word forgotten the next day.

However, that doesn't mean he held a minor place in my life. Quite the opposite. Unlike that chit-chat my early encounters with his work were never to be forgotten. I can recall the day I purchased Binky Brown as if it were last week-- even though it was 40 years ago.

This was my first year of art school. I'd arrived in Toronto immediately after graduation. Direct from Hicksville to the big city. Everything was new to me. And a bit scary. I'd never ridden a streetcar or had an apartment or drawn a nude model or been in a comic book shop. In fact, I avoided the comic shop specifically since I had such little money. I knew I couldn't be trusted in there. Still, after about a year I caved in and walked though the doors. Up till then the only comics I had ever read were Marvel comics but now I was looking for something else. I suppose I could pretend I had outgrown that superhero stuff but that wouldn't be the truth. I was still a very naïve, unsophisticated kid. Still the small town boy. So, in retrospect, it surprises me that I walked past all the genre comics and began digging in the underground section. I'm honestly not sure why. I guess a year of art school had sunk in. Possibly I'd read a single Crumb comic by this point. I dunno. Maybe I was looking for another one.

All I know for sure is that I walked out of there with two comic books under my arm. How I selected these two I couldn't guess. I suspect it was practically random. Certainly luck was involved because, out of the two, one would have an enormous effect on me. The first comic is largely forgotten. Some sort of Rock and Roll themed underground issue. The second, of course, was Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary.

I bet there could be a quiz among cartoonists of my post-underground generation. A kind of, "Where were you when you first read Binky Brown?" sort of thing. It's that vivid. I remember the apartment, the time of day, the very feeling of it all when I closed the back cover and put it down on the futon. I don't want to overstate—get histrionic about it—but I was pretty flabbergasted. I can honestly say I had never read anything quite like it. I don't think I immediately grokked to it being a great work of art. I suspect that what I really felt was, "Here is a comic book drawn by an insane person." It was too far outside my schoolboy set of experiences to properly classify. It was a mindblower, f'sure. The closest thing was seeing Eraserhead earlier that year. That knocked me for a loop too. I came out of that theatre like a zombie and just went straight home in a fog. Didn't even really said goodbye to the folks I went to the movie with. These two different works had much in common, actually. Both of them are transgressive, absurd, obsessive... but more importantly both have a kind of gritty unpleasantness to them that was shocking to someone like me. Someone mostly exposed to mainstream entertainment. Both were dreamlike, nightmarish really, and both had a kind of lingering 1950s earnestness to them. Yet this '50s aesthetic was seriously undercut by an unsettling vulgarity. I wasn't all that ready for it. I thought about both of these works for a long time afterward. Years. And Binky being a comic book (and myself an aspiring cartoonist) may have hit closer to home. I remember trying to describe the comic to friends several times. And failing. I couldn't get across how disturbing it was to me. The book felt dirty, emotionally upsetting, and yet it wasn't just a freak show. Some element of the profound hung over the reading experience.

Not exactly a Stendhal syndrome... but perhaps the funny book equivalent. The thing is, what really got through to me was the life experience Justin was imparting in the book. Yes, the imagery was funny and odd and disturbing—even off-putting—but the sense of his upbringing, his turmoil and the odd neurotic journey - that came through. Like a lightning bolt. And it sunk in deeply and in a lasting manner. Just like the best of literature. But unlike literature, I didn't come to the book expecting to be encountering a classic. I figured it was just another dirty comic book.

Eventually, of course, time passed and I came to an understanding of who Justin Green was and what the Undergrounds were all about and what a singular work Binky Brown genuinely was. Sure, there were certainly other great undergrounds, lots of them, but nothing ever unseated me quite like Binky. I came also, in time, to recognize it as a towering work of comic art. A rare instance when an artist produces their magnum opus right out of the gate. I suspect for Justin it might've been a bit of a milestone. He certainly never topped it. Probably something like Maus for Spiegelman. A blessing and a curse. Whatever the case, that comic had a lot to do with teaching me, in clear bold strokes, that comics could be REAL ART - with all the capital letters. Even though my work and Justin's couldn't be less similar I consider him a very important mentor in my own path to being an artist.

I've rattled on here as if Binky was the only good thing Justin Green ever did. I regret that. I didn’t intend to give that impression. No, I'm a fan. I devoured his sign painting strips. Those really spoke to old-timey me. I've read them a hundred times. And I think "Th' Kiss-Off" from Bijou 6 (if memory serves) is one of the best short comics ever written. But, no surprise, Binky will be his lasting legacy and that is nothing to feel bad about. I mean, not every artist gets such an iconic high water mark to their name.

I don't think, when I met him, I told Justin how affecting that comic was to me. I think I was too embarrassed to say anything - assuming that he had heard, "that comic blew my mind," a thousand times. I don't regret saying nothing. As one gets older you come to see that it is almost impossible to impart experience to others via some idle chatter. Not with art, though. There you can do it. Binky Brown is the proof.

* * *

(cartoonist)

I didn’t really know Justin Green too well, but he was a hero. There isn’t much I can add that hasn’t been said here. He made personal comics about personal pain. Before that was a product category. And he made them funny. The domino effect of Binky Brown changed the face of comics forever. You know that.

We did once have a long online conversation about the (alleged) powers of apple cider vinegar (which apparently border on the miraculous). I can't remember why. It was definitely not the conversation I wanted to have with Justin Green. But it was the conversation he wanted to have with me, and sometimes you don't argue.

I was skeptical, but Justin had absolute faith and convinced me to try a tablespoon of apple cider vinegar daily, on general principle. This was a few years back and here I am, still taking a tablespoon of apple cider vinegar daily, on general principle. What me worry?

The morning after his death I mentioned the news to my “visual storytelling” class. As expected, they had never heard of him. So I talked about Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary, and why it was important and great and horrible and hilarious and urged them to read it right away. They were skeptical and possibly wondering if I was just making it all up. I went to Amazon to show them, to situate it squarely in 2022 reality, but could not find the classic text anywhere in print. Wtf?

Later I went on Facebook to re-live our apple cider vinegar exchange. But that wasn't there either. In fact, Justin's account had vanished entirely. Or had it? Omg!

Eventually I pieced it together. It was me that wasn't there. I had been blocked on social media by Justin Green. Wtf? Omg! Mea Culpa? And meanwhile here I am, drinking this cat piss.

But truth be told, I guess I'm kind of used to the cat piss now and I'll probably just keep taking the stuff. And maybe you should too. On general principle. Or at least until somebody puts that book back in print.

So long Justin.

* * *

(comics historian, art collector, author)

I first met Justin in person at his studio in San Francisco in 1972.

I was staying with S. Clay Wilson for a weekend, and Wilson suggested we go visit "Guilty Green."

Justin was hard at work on his Binky Brown 40-page epic, and had a clothesline stretched from one wall to the other, with the pages clothespinned in order, so that he could view them from his drawing table.

I admired the originals to the inside front cover and also the back cover and asked Justin to hold them for me after they'd been photographed for printing. About 6 months later, I received a fresh copy of Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary with a "Hot Off the Press!" inscription by Justin. I paid him for the two original pages.

Not long after, Justin called me on the phone saying he needed rent money and was willing to sell me all the inside Binky pages at $10 each. At the time, I really didn't want to have original art that I did not have the room to display, and also had the feeling that I would later be thought of as "Guilty Bray" for taking advantage of his situation. I sent him some money to hopefully tide him over and he could send me a page or two when he found something he thought I'd like.

He DID end up selling the pages to a San Francisco lawyer, Albert Morse, for not much more than the $10 rate. Morse placed them in a box and left them in a vault until his passing. In 2010, his widow wished to disperse of all of Morse's collection, and contacted Art Spiegelman. Luckily, Artie contacted both Jay Lynch and myself, saying that Mrs. Morse was in contact with Heritage Auction House, and their proposal was to sell off the story page by page, for best financial return.

I got her on the phone and suggested an all cash offer that would save her all the trouble of dealing with this art. She also had works by Crumb and other artists that could go to auction.

I drove up and bought the work in 2010, and in January 2012 was asked by Spiegelman to loan the entire 40 pages for exhibit at the Angoulême, France, comics festival. Curators from the comics festival in Amadora, Portugal, saw the works and wanted to exhibit them in their show later that same year. They brought my wife Lena Zwalve, myself, Justin, and his wife, artist Carol Tyler, all over for a week, all expenses paid. I did have private talks with Justin a few times about Binky, who said that it had been an albatross around his neck. But I assured him that it was so incredibly important and groundbreaking at the time he created it, to just roll with it, and keep creating more new work. I jokingly said that it was better than having CREATOR OF THE BIG MAC on his tombstone.

* * *

(cartoonist)

Justin Green's Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary is a pioneering work probably best known for its status as the first major confessional comic. And while I am duly impressed by the god-like prescience it must have required to divine a brand new canon, to my eye, the primary power and visionary brilliance of this work lies in its unflinching focus on childhood suffering.

Green did not set out to create this work armed with a diagnosis (that mediating thing which can sometimes offer enough space and distance to safely introspect). He had no words for his condition. That language would come later: "Obsessive. Compulsive. Disorder.”

This kind of wordlessness is the natural state of infancy, and learning to communicate—desire, fear, pain, joy, hunger, rage—is the primary labor of most childhoods. And so, as a grown man without language for his particular kind of suffering, Green was uniquely equipped to depict (and to honor) the psychic pain and confusion of his child-self. Within a decade of publishing his debut longform work, he would come to believe the falsehood that unfettered disclosure is invariably shameful, that perhaps more elegant work leaves a little something to the imagination. In a 1986 interview for The Comics Journal, Green told Mark Burbey that Binky Brown "...[is] kind of shocking for me to look at. I'm not especially proud that I put so much of my internal life on the line." But this is precisely what gives the work its power.

This is not to say that art is only as valuable as the secrets the author is willing to tell, but it is to say that this particular kind of defenselessness allowed Green to depict the mania and terror of untreated and unmedicated childhood mental illness in a way that has not been replicated since. Unmatched in its raw and brutal vulnerability, Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary could only have been written by someone still sick, still hurt, still frightened, and still confused. In this sense, Green's work is also the first example of autobiographical graphic medicine. This work is a case study on a neuropsychiatric disorder written by a man living with an undiagnosed neuropsychiatric disorder. Binky Brown is a book about getting swallowed up, and Green wrote it from inside the belly of the whale.

This chaos has a redemptive quality - he effectively elevates his child-self into a fully realized human being. And then, remarkably, he transcends even that (which is typically considered the high watermark of autobiographical disclosure). Binky Brown is a dizzying portrait of a child mystic: a person for whom God and sex and suffering and ecstasy are inextricable. There is a chance that all young people are capable of this kind of ascetic eros - the kind of union with the divine that is so intimate and honest that it feels physical, almost painful, like staring into the sun.

Most of us lose our capacity for this kind of rapture somewhere along the way. Those of us who cling too tight to it always end up cloistered in one way or another - in convents, in hospitals, in bottles. For the reader who has managed to grow up and build out a life unsequestered, Green's work offers a window in. And for those of us who are still locked up, Green's work is good company.

* * *

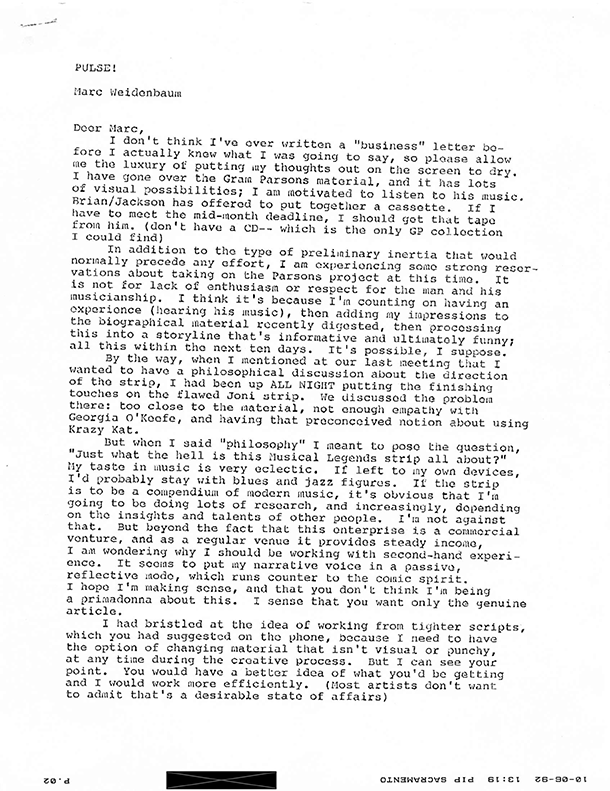

(former senior editor, Pulse! magazine)

Justin Green lived in Sacramento when I did, in the early 1990s. As I write this, it's been barely a month since he died. I still grieve for my friend who taught me about art and life, emphasis on the "and". A folder filled with remnants of our collaboration provides some solace.

I'd moved from Brooklyn to California's capital city in 1989, a year out of college, to take a job as an editor at Pulse!, Tower Records' print magazine. After two years, I suggested to my fellow editors that we experiment with comics in the magazine. The first two artists I signed up were local. Having never edited comics before, I looked for people whom I could work with in person. This was late 1991. Email was rare, cell phones even more so. We spoke by landline, sent faxes, wrote letters, and met in midtown Sacramento cafes like Greta's and the Weatherstone. The first of these artists was Adrian Tomine, who I knew lived in town because his mailing address appeared in his self-published Optic Nerve, one of numerous minicomics I was buying at the time. The second was Justin Green.

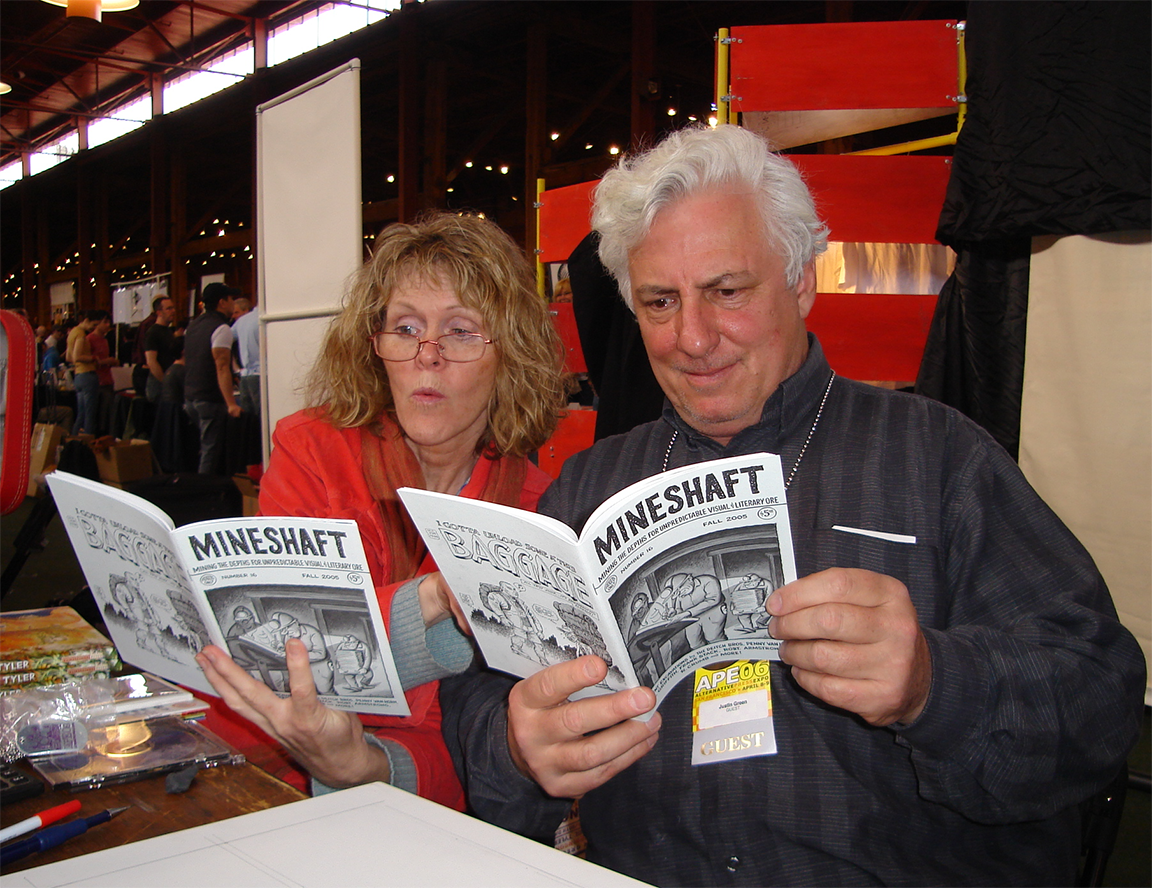

I was aware of Justin's comics from the magazine Raw, the 1991 issue of which listed Sacramento as his location. I tracked him down, and thus began the longest-running comic that Pulse! published, for upwards of a decade. It's comically—forgive the common pun—absurd that the first two artists I published in Pulse! were so talented, given that I actively, at the beginning, limited myself to locals. It’s also cosmically—pushing the pun further—intriguing that one of them had, decades earlier, produced an ur-text of autobiographical comics, and the other was among the youngest artists pursuing that line of creative activity. Arrangements were formalized at the end of 1991, and their initial Pulse! comics appeared in the first issues of 1992. Justin's presence in the magazine no doubt helped as I built our roster of contributors, who in time came to include his wife, Carol Tyler.

There are a lot of things I could share about working with Justin at such length and regularity. I could talk about his love for glass ink nibs. Or about how he aggressively remade any scripts supplied by writers other than himself (I wrote a few), always for the better. Or about his painstaking use of multiple drafts to refine stories. Or about how the strips' seemingly most surreal grace notes were often there from the first sketch (whimsy as linchpin). Or about how telling it was, to me, that this elder statesman of underground comics was always open to editorial input, while some far younger artists (not Adrian) flinched and bristled at editing, needing to be sensitively coaxed.

The thing I think is important to share in the context of The Comics Journal is how central financial matters were to Justin's comics. He was, in the truest sense, a working artist. His art (in Pulse!, other commissions, sign painting) was defined by his need to make a living. It's understood how Justin’s autobiographical work was informed by his religious upbringing. It's just as important to understand how, in adulthood, practical matters determined and shaped his self-expression. One marvel among many of Justin's comics is just how much of himself he brought to what was, always, the next job.

* * *

(cartoonist)

Sometime in the 1990s, I had the good fortune to be on a signing tour in the Bay Area, along with my Drawn & Quarterly friends and fellow cartoonists, Chester Brown and Seth. And, I distinctly remember meeting two of my all-time favorite cartoonists, Dan Clowes and Carol Tyler. And, I have photographs to prove it! The funny thing is: I don't remember if Justin Green was there or not! I certainly knew who he was, his importance, and his direct influence on my own autobiographical comics. And yet, I honestly can’t say if I ever met the man or not! He was that unassuming, quiet, and nearly invisible… IF he was even there at all! And, when it comes to memory, I consider mine above average. I knew he was married to Carol Tyler, and I clearly remember speaking with their daughter about "whether or not it was okay to pee in the shower." (Carol Tyler said it was!) But, if I had to put money on whether Justin Green was there or not, in any of the photos, residing in my photo album… the odds are 50-50! It's beyond strange to me that I can't remember if I met or spoke to him! And, I’m relating this because it seems TOTALLY appropriate (and consistent) with who (I imagine) Justin Green was… as well as the trajectory of his comics career.

Justin Green, in many ways, is the quintessential "invisible cartoonist." His influence is vast and all-pervasive, especially when it comes to "confessional, no-holds-barred autobiographical comics." His seminal work, Binky Brown, influenced Crumb and Art Spiegelman (and probably Harvey Pekar), who in turn influenced EVERYONE, including myself. And yet, Justin Green is not a household name. His books are no longer in print, and his death felt more like a passing breeze than a ton of bricks. Yet, he's everywhere… all-pervasive, unobtrusive, and invisible. He even greatly influenced his wife, Carol, who (in many ways) "took the ball and never stopped running with it." (She has the discipline to keep churning out the pages, and she never stops growing as a cartoonist/writer. She continues to impress me—excelling and accelerating!—as she ages. Much like Kim Deitch, now that I think about it.)

As for Justin Green's work and cartooning, on a purely visual level… all I can say is: I don't think it's for everyone. Even for someone like myself, that should be his biggest fan - it's complicated. I find his early work to be very crude and off-putting. He had an odd drawing style, cramped lettering, and an overly-dense approach to most of his comic pages. And yet, I still find it charmingly idiosyncratic. But, it took me YEARS to arrive at this perception and ability to appreciate his work, despite his fearless writing and willingness to expose himself, so unapologetically.

I currently only own two of Justin Green's books: The Binky Brown Sampler and Sign Game. I remember stories like "Th' Kiss-Off," as well as his pieces in Raw magazine, but I honestly couldn't tell you if they're included in The Binky Brown Sampler or not. And surely, he must've had some stories in Weirdo, but nothing comes to mind. What I'm trying to say is: I always assumed, instinctually, that The Binky Brown Sample contained Binky Brown, Sacred and Profane, and some short pieces to fill it out. Never have I thought of it as a definitive collection. That's something I remain in a state of constant expectation and craving for - a COMPLETE omnibus-type collection. Yet, I know that’s neither realistic, nor imminent. Still, I have no idea how many pages of comics he produced, total. All I know is: I want them. ALL of them. Because, like I said - with time, I grew to love every stroke of his deeply personal pen.

And the turning point, for me, began with his collection, Sign Game - which is my favorite of all his work. Those monthly strips he produced for Signs of the Times are his high-water mark, if you ask me. They're still jam-packed, idiosyncratic, odd strips… yet, they're slightly more polished than anything that preceded them. The lettering is virtually perfect. And the minutiae of his subject matter (sign painting) proves (or rather reinforces) the "message" of his earlier, autobiographical work. And that message is: ANYONE'S life is interesting, if handled and told properly. (And by that, I mean: with skill, draftsmanship, unflinching honesty, and great effort.) And the "message" of Sign Game is similar, which is: ANYTHING is interesting, if handled and conveyed properly. And that goes as equally for sign-painting as it does for marble-collecting, butterfly-hunting, you name it. If YOU find something interesting, and you’re more knowledgeable about it than the man on the street… you need look no further for subject matter. Comics don't necessarily have to be story-driven, any more than they need to be superhero-driven power fantasies. And these two salient points, Justin Green drove home, better than anyone. "Write what you know" is always good advice for any author…only, the medium of comics seems to have gotten the memo late. (And, the "memo" isn't exactly "nailed prominently on the bulletin board" either.) I mean… sure, everyone owns Maus, but how many people own a copy of Sign Game? If it were up to me, Sign Game would remain in print (as well as in hardcover) in perpetuity.

(The real shame of books being out-of-print is that they're NOT out there, winning over new readers. They're just dead and invisible. And, as a cartoonist whose own books are now ALL out-of-print, I know of which I speak. Everyone just wants something new. There's economical considerations, always. It sucks, because then a book's "worth" becomes equated with its popularity and demand for it… which isn't always an indicator of great art. Books like The Catcher in the Rye and To Kill a Mockingbird stay in print, partly because they're SO highly regarded that teachers continue to use them as tools and shining examples of great writing. The inference being: if a book goes out-of-print, then it somehow "deserved it," because it wasn't worthy of future study and analysis. Yet, a book like Sign Game never even had a chance. Comics in the United States remain marginalized, no matter how many Marvel graphic novels keep flying off the shelves. And while I'm ranting, I'll also mention Peter Blegvad's fantastic collection of horizontal one-pagers, Leviathan. This book, like Sign Game, was produced as individual strips, whose cumulative effect in reading amounts to something indescribable. In fact, I often think of both books, simultaneously, in that I have a tremendous love for the uniqueness and execution of each. Yet, both remain out-of-print and somewhat obscure. Sigh. Now I'm depressed.)

Moving onto Justin Green's final collection, there's Musical Legends [Last Gasp, 2004]. I bought and read every single, microscopic word of this book, when it came out… and then, I promptly sold it to a friend. Why? Because the damn lettering was SO tiny, and the pages were SO jam-packed… I knew I never wanted to subject myself to another reading of it. (I consider this a tragic failing on the publisher's part, or perhaps Justin Green's. Either the book could've been printed MUCH larger, or the pages could've been re-formatted for easier reading. As it was though, it was a SLOG to get through.) (As was Chris Ware's Rusty Brown, which I recently read. A great book… but WHY print it so small and uninviting? It makes no sense to me. I had to hold the book an inch away from my naked eye in order to properly read most of its microscopic lettering!) Anyway, with his one-page musical bios, I think Justin Green also reinforced his point of: ANYONE'S life is interesting, if told properly. And, it doesn't even have to be autobiographical… it can be biographical as well. And with every page of Musical Legends, he found the most obscure and "interesting to him" tidbits to include. And again, Justin Green seems to be saying: "If it's interesting to the artist, then it's his or her job to convey that, and get you on their side." And that's really Justin Green's legacy to me, in many ways… because after reading his work, that's the internal realization one takes away from it--

"Build it, and they will come." Or rather: "Draw it, and they will come." Or not. It's not the artist's job to strive for popularity. The starting point is always one's greatest interests and passions. The initial audience is always oneself. And the vehicle to get there is always an embrace of the disciplines of craftsmanship, coupled with hard work. And despite adversaries such as public indifference and financial hardship, the artist must always press on… always doing their best… always giving maximum effort.

This was how Justin Green approached sign-painting, as well as comics. He was a true artist, with a capital A. And the ripple effect of his efforts can never be adequately tabulated.

Now someone… PLEASE give me that Justin Green Omnibus!!

* * *

(cartoonist)

I first met Justin Green in the early 1990s in New York City. Having read his classic Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary as a teenager and being floored by it, I was expecting some sort of hypersensitive, fragile character still shaken from his childhood experiences. Not so.

He was friendly, open, easy-going, capable of talking about anything, and, if it interested him, he could talk a blue streak. Obsessively - music, art, politics, color theory, you name it. Once he got onto something, he rarely got off.

Because of my admiration for Justin, I was nervous about showing him my work. He could be critical—preferring my color over my black-and-white work—but, really, he just wanted to help and impart what he knew. Once he began talking about inking techniques or cartooning tools, he became consumed with how they worked and their proper usage. Not in a hectoring way, but because it mattered to him.

What didn't matter to Justin was what everyone else was doing.

So much of comix, during the heyday of the Underground, was self-consciously taboo-busting. "You say I can't draw it - just watch me!" A lot of the comix movement was really reactive, even assaultive unless it was just about silly hippies getting high.

Justin had no such interests. There wasn't too much sex, violence, or drugs in his work. Mostly his characters (including Binky) seem a little confused by life, lost, never hateful, but not in control of the situation either. And even though Justin's work was often funny, it's not exactly a good time comic book joyride - it kinda hurts.

Justin once told me he had a dream in which his dead father appeared and said to him, in regards to Binky Brown, "Such things should never be a matter of public record."

I love that because I felt like I knew what he meant, that there are things in our pasts, in our selves, that should remain buried there, deeply, not unearthed, excavated (especially in comic book form!) for the world's perusal.

This visitation of Justin’s father - it's like the ghost of "correct" behavior haunting us as we face down our demons on the page. How much do we want to expose? How much is too much? Have we crossed a line and done damage by putting it out there? And, finally, how far am I willing to take this?

Justin is most remembered for Binky Brown, but one panel that really stands out for me is in his adaptation of Faust that appeared in Arcade #2. There's a drawing of Projunior (the underground comics Everyman) gazing into the future thinking, "Well, one fine day I'm gonna become a renegade cartoonist, and I'll do what I damn well please to do!"

And, for me, now Justin Green is the ultimate renegade; where many other cartoonists pushed the envelope with sex, violence, and general badassery, measuring their success (to more than a small degree) by how many were offended, Justin's work was shocking because it went deep into his own traumas, rather than attempting to inflict them on the reader. Though his style was ungainly, unusual, and somewhat rough around the edges, what it captured often enough was that off-kilter, not-quite-right suburban ennui - the feeling that there's something else going on, something that has to stay hidden.

It's easy to go outside the bounds of what's acceptable to get a big reaction. Just calculate what upsets people - and draw it! Yell fire in a crowded movie house, watch people freak. Comics have always been a place for that kind of delinquency. It's fun. I've done it myself. But it's making the work from the outside in. Much tougher, and much riskier, is going from the inside out. To depict yourself at your most vulnerable, lost, afraid - and that's what Justin did with Binky Brown.

The great paradox is that by being willing to expose that weakness, his work became powerful. By showing himself standing up psychically to his childhood experiences, he gained the ability to break free of the hold religion had on him.

A showdown with the Virgin Mary is the climactic scene of Binky Brown. Here, Binky shatters this graven image of the all-powerful Catholic Church—the Virgin Mary—thus freeing himself (at least in part) from his childhood curse.

This scene was inspirational in my own graphic memoir Chicago. My character at age 19, disillusioned by art, suburban life, and especially his family, has a violent showdown with himself.

The house empty, he wanders naked from room to room, finally taking his father's handgun up to the attic. There, shooting wildly, he accidentally blasts his grandmother's portrait, symbolically destroying his own family lineage.

That explosive catharsis, of breaking violently free of societal norms and what they impose - it's a scene that Justin Green's work made possible.

Of course, Justin could do all of this because he was a master storyteller, a great artist, and capable of being very funny too.

Which brings me back to where I started. Justin, when I met him, didn't seem damaged, fragile, or compromised by his experiences. Life hadn't destroyed him.

Which may be something for all cartoonists to consider when facing difficult material. That you and your work may come out stronger and better for the journey.

* * *

(art director, graphic designer, publisher of BLAB! magazine)

Having witnessed the freewheeling, taboo-breaking spirit of Underground Comix as the scene was unfolding, I couldn't help but sense a kinship between this body of work and the notorious EC comic books of the 1950s. EC gave us Mad. The Underground gave us Zap.

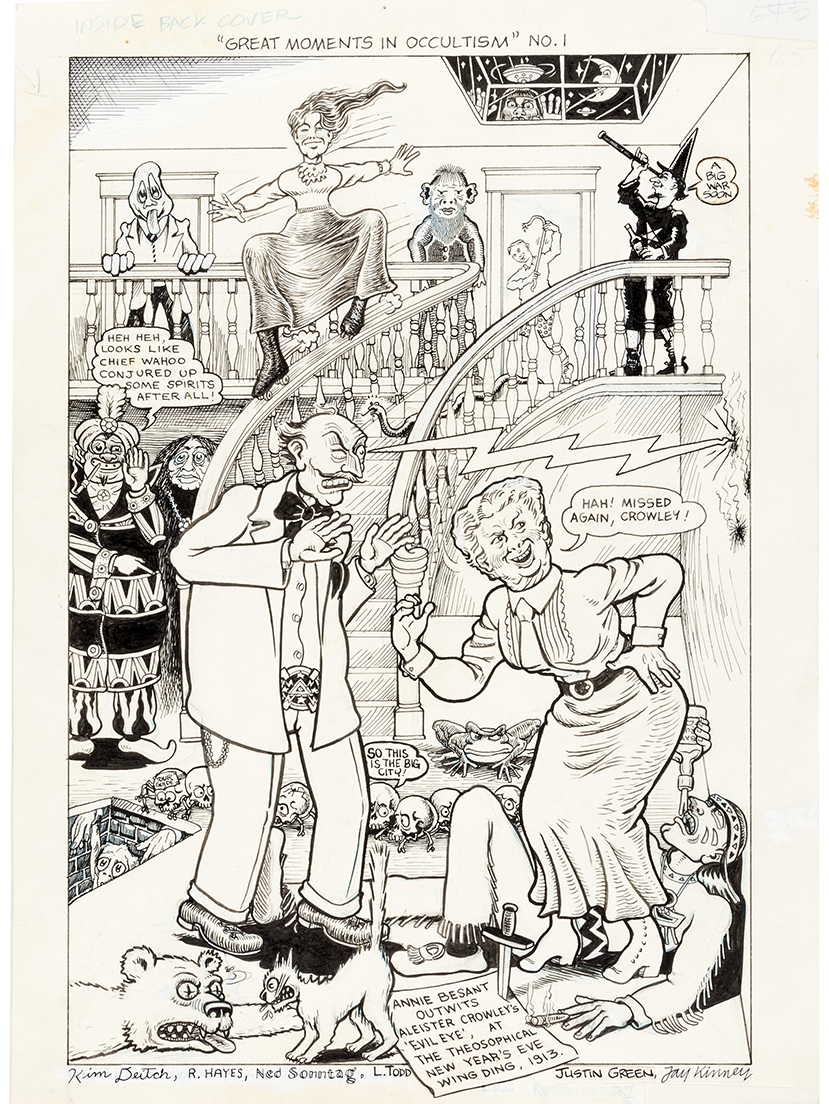

Zap's off-the-wall aesthetic ignited wave upon wave of Underground Comix. Anthologies such as Bijou Funnies, Laugh in the Dark, Young Lust, Slow Death, Skull Comics, and Real Pulp Comics crackled with prodigious talent by the likes of Kim Deitch, Art Spiegelman, Jay Lynch, Justin Green, Bill Griffith, Jack Jaxon, Rand Holmes, and Roger Brand. Along with the Zap collective (Robert Crumb, Rick Griffin, Victor Moscoso, S. Clay Wilson, Gilbert Shelton, Spain Rodriguez, and Robert Williams), they were doing twists and turns with the cheap newsprint medium my teenage eyes had never seen before.

From 1968 to '73, the form rippled with excitement, but with the collapse of the counterculture came the collapse of comix. By 1976, after Art Spiegelman's and Bill Griffith's brilliant Arcade bit the dust, the party was over.

Ten years following the genre's untimely demise, I invited the movement's key artists to pen essays about their childhood memories of EC that I would compile in a self-published, digest-sized fanzine titled BLAB!

Of the thirty talents to whom I reached out, twenty-six replied - all with a resounding "YES!"

One by one, the cartoonists' recollections trickled in. Robert Williams declared, "They poisoned a generation, I'M A LIVING TESTIMONY!" Kim Deitch revealed, "We died the death of dogs when Mad suspended publication." Frank Stack proclaimed, "EC proved that the comic book could be a real art form." S. Clay Wilson explained, "I haunted the musty, narrow, wooden-floored aisles of cheaper drug stores on 'O' street, in hopes of finding the odd EC."

The closing line of one memoir in particular struck me right between the eyes. It sounded like something F. Scott Fitzgerald might have said had he been exposed to EC comics as a child. "The nostalgia I feel for those comics," wrote Justin Green, "is not only for their high level of craftsmanship, but for part and parcel of my lost innocence."

I found this statement extremely touching. Not at all what one would expect from an underground cartoonist.

And that was the brilliance of Justin Green. From single poetic lines to a neurotically-charged illustrated epic, he brought a unique, artistic verve to the legacy of Underground Comix.

* * *

(cartoonist)

Well, first of all, Justin and I never met, but we talked on the phone back in 1971. I was visiting my ol' pal Jay Lynch and Justin called up. Jay told me to get on the extension because he wanted the two of us to talk. We had an interesting conversation of which I don't remember anything. Years later via Facebook we became friends and started to correspond. He became a very good friend then. We kept in touch until roughly a few weeks before he passed. He never mentioned to me that he was ill so, of course, I was shocked when he did pass.

I always admired Justin's work ethic. He did a tremendous amount of comic book work that has obviously left a strong impression on a lot of people including me. I was surprised when he started his sign painting business which quickly grew and he just got better and better at it. I also liked all of the paintings that he did in the past few years - especially the last one. Justin was certainly one of a kind with a VERY unique drawing style and his writing was certainly original and fresh. I will miss him.

* * *

(cartoonist, minicomics historian)