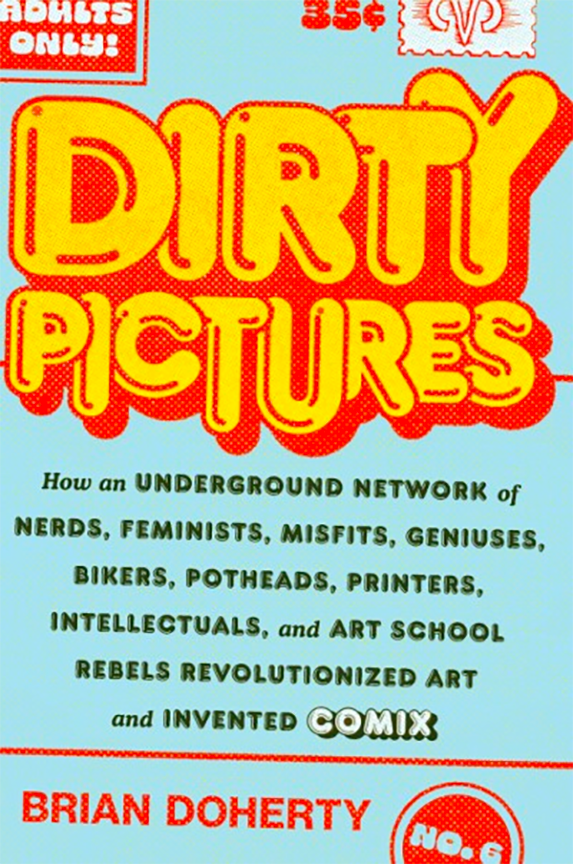

Dirty Pictures: How an Underground Network of Nerds, Feminists, Misfits, Geniuses, Bikers, Potheads, Printers, Intellectuals, and Art School Rebels Revolutionized Art and Invented Comix, the ambitious new book by Brian Doherty that chronicles the rise and staying power of the underground comics movement, has a very long title. And for some, particularly some of the still-living cartoonists whose stories and words appear in the book, it's not a particularly good title. In an informal survey of a handful of cartoonists covered in the book... well, they hate the title. And the art direction of the cover, generally. I could quote at length the comments of a number of people in the book, whose reactions to the cover include "ridiculous," "wrong headed," "visually illiterate," "hate," and "what was he thinking?," but you get the point.

The other thing to get out of the way right up front here, is that Dirty Pictures is a more than 400-page book that covers the history of a visual medium, yet it contains no images. Not a single one, except the author's publicity headshot photo on the jacket flap. No pictures at all... in a book called Dirty Pictures. That's a pretty interesting approach. But more on that later.

While all of the people I talked to about Dirty Pictures had a somewhat... "baffled" (is probably the best word) initial response to the book, I want to make it clear that none of them had actually read the book. They were basing their thoughts mostly on seeing the book's cover on their computer screen or phone, and learning that it contained zero images. Or they said they disliked the cover's design and its use of the pseudo-pornish Frankfurter Highlight typeface. So there's likely a bit of contempt prior to investigation going on. I am hopeful that they will move beyond any initial visual resistance of the book and give it a read because I am interested in their take. I, myself, found it ultimately to be for the most part an entertaining and enjoyable read—I learned some things!—and think they will learn some things too.

* * *

What will one find upon opening Dirty Pictures? A lot. The book is an extremely detailed and thorough account of the stories of the many connected and unconnected people whose pioneering work collectively came to fall under the umbrella of underground comix. For a newcomer to the subject, the book offers an endless supply of material and stories to learn about this important and groundbreaking movement, and Doherty does his best to connect the breakthroughs of the UG cartoonists to the impact their work has had on today's popular culture. What Dirty Pictures really does is put a lot of existing material into one linear narrative, tracing the early days of the UGs to how some of their impact—and fallout—is viewed in current times.

The book opens with the story of Robert Crumb's infamous "Joe Blow" strip from Zap #4 and concludes with a wrap-up of where some of the surviving early pioneers are now—several, including Justin Green, have died since Doherty turned in his manuscript—including a mention of the call for Crumb and his like to be "transcended and rejected" (Doherty's phrasing) during an awards ceremony speech at the 2018 Small Press Expo. In between, Doherty explores the stories of Harvey Kurtzman's Mad, the early humor fanzines, the creation of Zap, the Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers, Last Gasp, Print Mint, Kitchen Sink, Rip Off Press, women cartoonists in the movement, gay comics, the financial and legal struggles of the underground publishers, Justin Green's Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary, and Art Spiegelman's work on Maus, Raw, and Wacky Packages/Garbage Pail Kids at the Topps company. Doherty also goes into the history of Crumb's Weirdo, the Air Pirates' legal battles, alternative weekly newspaper comics, and some stuff about the early days of Fantagraphics and alternative comics and 'zines. And many other things along the way.

Dirty Pictures casts Crumb and Spiegelman as the central characters in its narrative because, as Doherty told podcaster Gil Roth on The Virtual Memories Show, the two emerged as the most successful figures coming out of the underground world. Of course, Crumb was central to the undergrounds from the very beginning—and later reemerged in the public eye with the release of Terry Zwigoff's 1995 documentary Crumb—while Spiegelman's profile among the general profile really evolved later, when Maus won a Pulitzer Prize in 1992. Doherty felt that both Crumb and Spiegelman were deserving of large-scale biographies of their lives, and used their prominence as a selling point for Dirty Pictures when approaching the mainstream publishing houses he was courting (unaware that curator/historian Dan Nadel was also working on a biography of Crumb, which will be published by Scribner):

I was thinking, again, in a business-minded way. I'm like, okay, why would a trade publisher want this book? Because no trade publisher has wanted this book before. You know, [underground comics historian Patrick] Rosenkranz's work is all published by comic specialty houses like Fantagraphics. So I'm like, maybe there's a reason no standard New York trade press, has done a book like this? But I began thinking, like, it's undeniable that at least Robert Crumb and Art Spiegelman are of such cultural significance, that, honestly they both deserve and ought to have—and in one case will have, but I didn't know that then—your sort of standard modern, you know, 600-page+ literary biography just about them. As I think the world knows now, Dan Nadel is doing that about Crumb. I did not know that when I was writing my proposal. Interestingly, I literally... I think my timing on this is correct. Like, three days after my proposal hit the market, the news that Nadel had sold his Crumb biography became public in the trades. I had mixed feelings about that. I thought it might harm my ability to sell my book. It did not. I mean, it did not in the end. I initially thought, boy, I wish Dan had done this, started this five years ago so that I could read his book and incorporate it into mine, because, certainly, I'm very excited to read it when it's done and it definitely would have made my book better if I'd had whatever Nadel is doing to draw upon. But at any rate, it seemed obvious to me that the [book's proposal to a prospective publisher] needed to front and center Crumb and Spiegelman because I thought that's what your sort of cliched New York intellectual is going to be able to grasp hold of most. Like, they they may not have heard of Justin Green, and they may not have heard of, you know, Victor Moscoso... but definitely they understand that Spiegelman and Crumb are important.

The stories of Crumb and Spiegelman are joined by those of other important figures, including Justin Green, Jay Lynch, Bill Griffith, S. Clay Wilson, Spain Rodriguez, Skip Williamson, Denis Kitchen, Gilbert Shelton, Kim Deitch, Jay Kinney, Jack Jackson, Rick Griffin, Rory Hayes, Victor Moscoso, Dan O'Neill, Bobby London, Gary Arlington, Shary Flenniken, Vaughn Bodē, Diane Noomin, Robert Williams, Ron Turner, Aline Kominsky-Crumb, Howard Cruse, Françoise Mouly, Harvey Pekar, Trina Robbins and many others. It's a lot of ground to cover, so I decided to ask the author about his approach.

* * *

What was the one unifying theme that connected all of those people and events? To Doherty, it was "dirty pictures". Others may disagree and instead point to "artistic freedom" and "self-expression," which comes in many forms. Were there "dirty pictures" in some, or a lot, of the undergrounds? Yes there were. And a lot of drugs and horror and fantasy and humor and personal stories and activism and science fiction and parody and everything else you can think of. Some of it was great, and a lot of it was really, really bad. Just like every other genre of comics. I asked Doherty, who is senior editor at the libertarian magazine Reason and author of This is Burning Man: The Rise of a New American Underground (Little, Brown, 2004), if the book's title was his idea and if he was aware that it was viewed as problematic by some of the people the book covers.

"It was not my idea but [I] agreed to it," he replied in an email. "I am not unaware of those attitudes... not only am I aware I get and appreciate and such offense, some of which we directly knew about beforehand and others of which could be reasonably predicted, did lead to moments of second guessing. But for an item that needed to sell, or try to, to a semi-mass audience outside devotees of the coterie, something textbooky felt it would not serve the work as an item for sale. A book title has commercial necessities in audience-catching that can't always perfectly match or fully sum up a work in whole. I think it's defensible... but totally get [how] someone whose work is being discussed would bridle at having their [life's] work reduced to 'dirty pictures'.... But the title is the title, and the book is the book, and while a journalist ought not and cannot make 'keeping his sources and subjects happy' (beyond trying to get facts straight and interpretations defensible) I should hope anyone who reads even any 10 pages of the book will see it clearly arises from respect, affection, appreciation for the scene, the work, and the people in it, and a desire to carry forward the story of what they did to the future in way that gives them the importance and respect they deserve. And, for better or worse, 'dirty pictures' was the SINGULAR throughline I could defend."

And what about the book's lack of images? After all, isn't the book published by Abrams, whose tag line is "The Art of Books Since 1949"? More accurately, it is published by Abrams Press, the text-heavy imprint of the large Abrams umbrella, which includes the meticulously designed and illustrated Abrams ComicArts headed by Charles Kochman. Doherty said that he had planned to have Dirty Pictures contain at least the standard 16-page insert of images, but that was dropped due to "costs, journalistic issues with negotiating money with subjects of a book (tho that was MY worry, taken out of my hands by publishers decision to do none), and the fact that every reader is 10 seconds away from a selection of thousands of images by any given name far richer and looking better than we could have delivered…. The book's value, to degree it HAS value, is in what it is: a book of cultural history and biography. Images, he said, would come at the cost of text. "I genuinely and sincerely don't believe that another few thousands of words should have gone for the purpose of images that everyone everywhere can see in far greater profusion of choice and quality in 20 seconds than what this book was ever meant to be would ever have done."

* * *

Dirty Pictures joins a short list of good books covering the UG history, most notably James Danky's and Denis Kitchen's essay- and image-driven Underground Classics: The Transformation of Comics into Comix (Abrams, 2009); Mark James Estren's visual and fannish A History of Underground Comics (various publishers, 1974-2012) and Patrick Rosenkranz's excellent Rebel Visions: The Underground Comix Revolution - 1963-1975 (Fantagraphics, 2003). In October, Fantagraphics will publish Drew Friedman's Maverix and Lunatix: Icons of Underground Comix, a book of more than 100 new portraits and brief biographies of many of the key figures covered in these books.

So, how does Dirty Pictures compare to Rebel Visions, the book many consider the authority on the topic? Well, it's different in some obvious ways, but also certainly influenced by it; Rosenkranz gets at least 94 citations in Dirty Pictures' footnotes section—almost as many as Robert Crumb—and receives a gracious thank you from Doherty in his afterword. Indeed, appearing on Gil Roth's podcast, Doherty said he briefly considered abandoning the project after reading Rebel Visions:

In the past I have never written a book... in which you could say, oh, there's a book kind of just like that, that already exists, right? There is a history of underground comics that already exists. And there is and it's very good, and it almost stopped me for a minute.... I guess the overriding reason it didn't is I just really wanted to spend a year or two thinking about this stuff and writing about it. And I figured, you know, I'll let the market decide whether another such book is necessary. And then another couple of things I think I do that Rosenkranz didn't necessarily do… I try to extend the story thoroughly to the present. Like, you know, a third of my book happens after the mid-'70s, which is when the original wave of classic old-school undergrounds kind of started to fade away. And I also I think Rosenkranz was very embedded in what you might call the Zap aesthetic, right? Which was a big part of the undergrounds, but there was a lot more to the undergrounds. So I wanted to give focus to maybe some more of the nonfiction and the cause-related stuff and the female stuff and I hope I did a good job with that. So that's my definitive explanation for why I thought someone else should write a book like this.

Rebel Visions, in addition to being lavishly illustrated with numerous images from Rosenkranz's personal collection, also has the benefit of having an author with first-hand experience with many of the events and people covered in the book. Rosenkranz put 30 years of his life into Rebel Visions. In comparison, Dirty Pictures is not an insider's account. The content appears to have been compiled via Doherty reading back issues of The Comics Journal, books by Rosenkranz and others—Bob Levin's history of the Air Pirates, The Pirates and the Mouse (Fantagraphics, 2003), and Jon B. Cooke's The Book of Weirdo: A Retrospective of R. Crumb's Legendary Humor Comics Anthology (Last Gasp, 2019), to name a few—with extensive additional research of the collected letters of Jay Lynch at Ohio State's Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum and Denis Kitchen at Columbia University, plus emails, phone calls and in-person interviews with some of the still-living characters covered in the book. The book has 35 pages of footnotes.

"I don't think there is a single cartoonist of that '60s-'70s generation I had met (except Hal Robins, we were buddies thru Burning Man world) who I had met or spoken to prior to trying to write the book," Doherty told me in an email. "While I was someone with a lifelong love of comics and a burning desire to contribute to its historiography as a journalist, I was not someone with a lifelong love of the particular comix the people whose stories this book tell wrote about. Too-early exposure to them in the form of (my very first, and alas uncheckable, memory) murals on a college sub shop wall in 1976 and then in the pages of The Comics Journal and in a Gainesville comix/head shoppish operation in [the] late '70s called iirc 'The Duck Stop' made me think of comix as overly gritty, gross, 'real' in a strange and twisted way, telling me things about [the] adult world maybe I didn't want to know - too sweaty, too bizarre, perplexing. Even when I became a natural fan in the '80s and '90s of post-underground independent non-genre personal comix from the Hernandez Bros to [Joe] Matt, [Daniel] Clowes, [Peter] Bagge, Seth, [Julie] Doucet, [Chris] Ware, it took me years after I digested the aftermath to be able to turn to, first because [he was] most prominent and readily available, Crumb, and see there was something to this - but at first, yes, it DID feel like exploring an alien land, especially the stuff less obviously narrative. I think in many ways their graphic and storytelling innovations aren't fully backed in to later generations - something sui generis in them still."

Doherty told me his interest in doing the book was sparked while attending the 2018 San Diego Comic Con, which included a series of panels dedicated to underground comics. His interest in the topic grew a few months later while attending the Ignatz Awards at the 2018 Small Press Expo where cartoonist Ben Passmore made critical comments about Robert Crumb during a speech that resulted in a contentious online debate of Crumb's relevance in today's culture. Doherty then wrote an article for Reason, "Cancel Culture Comes for Counterculture Comics," that took a deep dive into the issues around the Crumb controversy. While Dirty Pictures is in no way a simple expansion of that Reason article, it does explore in depth the changes in our culture that helped shape the current climate we now find ourselves in.

"The notion that I would want to write a book like this arose, as I allude in my acknowledgements, sitting thru some 2018 panels at SDCC dedicated to their 50th [anniversary] as conventionally marked [i.e. the 50th anniversary of Zap #1]," Doherty told me via email. "I was exposed to personalities, stories, and a scene I knew smatterings about mostly from reading The Comics Journal over the decades, and had always wanted to be able to write a book that dug into my love and appreciation for comics. (As part of a desire to write books dedicated to my secret five lifetime passions, three of them I have now dealt with. The other two secret until I get to write books about them.) I began musing with Tom [Spurgeon] about the idea a new book about this history might be worth doing - he seemed to agree... when I seriously wanted to craft a proposal I had to ask him if he had any intention of ever doing so. (He did not, he said.) Between that idea and writing [the] proposal my editor at Reason invited me to think of a story topic that could unite my passion for comics and Reason's concerns, and I picked the then-hot controversy over the [Ben] Passmore-triggered public rethinking of Crumb and, in the eyes of Carol Tyler at least, anyone connected with him personally, editorially or artistically. It was in researching that article that I built the base of understanding needed to write a decent proposal (which was itself in first draft about one-quarter as long as the finished published book). That article focused on the history of legal attacks on undergrounds, to contextualize in what I hoped was an interesting way the current arguments over cultural/artistic attacks on them. The theme of modern mores questioning some of the attitudes, approaches, and stances of the early undergrounds that dominated that article are in this book, in what I think is a measured way - I think it would be absurd to tell this story extended past the late 1970s, which I did, and not address them, and in my opinion did so in a reasonably measured way that gave the controversies neither more nor less attention than they deserved, but if it erred in either direction I'd say it erred on 'less.'"

Doherty said his appreciation for the undergrounds grew the further he explored the material while researching the book and interviewing the creators and publishers involved in the movement.

"It was literally in the act of researching first the Reason article then proposal then book that I became a well-read fan of the original undergrounds, and the book was never intended to be an aesthetic judgement or deeply rooted in my opinions of the work, at times both for thinking it was needed to moor a current reader or I just couldn't resist the self-expression, I do some, I hope not too embarrassingly," he said. "But for sure my approach was more as biographer/cultural historian than comics critic or even fan, though I for sure have learned to love the (to use possibly lame language showing why I didn't do too much this in the book) raw POW of a Spain or [S. Clay] Wilson, the meticulously fresh worlds-on-page created with mindblowingly original styles of [Fred] Schier, [Dave] Sheridan, [Robert] Williams, [Victor] Moscoso, [Rick] Griffin, [S. Clay] Wilson page, the comic pleasures or genius of [Jay] Lynch, [Skip] Williamson, [Gilbert] Shelton and the fascinating early reaches into autobio memoir history and issues stuff in the late 70s. My personal joys of discovery would be Michael McMillan whose few pages strike me as ahead-of-their time wry inexplicable absurdist humor, and the body of work in full of Justin Green whose psychological depth and intelligence, high-level wry wit and goofiness, and how his lines on the page just EXUDE a unique perspective and mind. If a reader who has had a lifetime of loving this stuff thinks that my book shows I am not getting it on some level, it's an argument I'm willing to have, tho I did try to write a book that depended not much on my aesthetic judgment or appreciation of the work itself. I can now tell anyone who reads it without a deep background, is it worth my time to read a lot of old undergrounds? Absolutely it is---there is definitely a big element of 'to understand the evolution of modern art comix, or the 60s counterculture and its shifts' but also a lot of eye popping graphic pleasure, smart goofiness, and in some of the less celebrated-to-this-day stuff (I daresay tho happy to be corrected by later art history that the comics world has been PRETTY good about remembering and honoring MOST of the best of them) just a raw explosion of unmediated id that is a lot of curious fun."

"I was coming from a perspective of appreciation, admiration," he told Roth. "I think these were fascinating people who did important work that should be remembered, perhaps better than it is, That deserves to have a New York trade, work of prose nonfiction, telling their story...obviously, I believed all that. That's why I wrote the book."

* * *

I enjoyed Dirty Pictures and am glad that it exists. It strengthens the period's history and expands on some of what has already been published, especially in the case of the women cartoonists in the movement. But in places it does feel a bit rushed, almost as if it were a first draft, and it appears to me that the author would have benefitted from more time, a better copy editor, and a fact-checker. There are a couple of misspellings of key names that are unfortunate, and that makes me worried that there may be other issues caught by other readers. I am hopeful that there will be none. Does it break any new ground not covered by the books that have already covered the era? It'll depend on the reader. I know that I learned some new things—nothing earth-shattering, but usually interesting—and I am thankful for that. For a newcomer to the subject, it offers an endless supply of material and stories to learn about this groundbreaking movement, and Doherty does his best to convey his genuine appreciation of the importance of the UG cartoonists and the impact their work has had on today's popular culture. Is it a book that I'll find myself going back to for repeated readings? Probably not. Most likely I'll continue to pull out Rebel Visions when I want to refer back to a particular artist or story, or find an image. Is it a book worth reading? Yes.