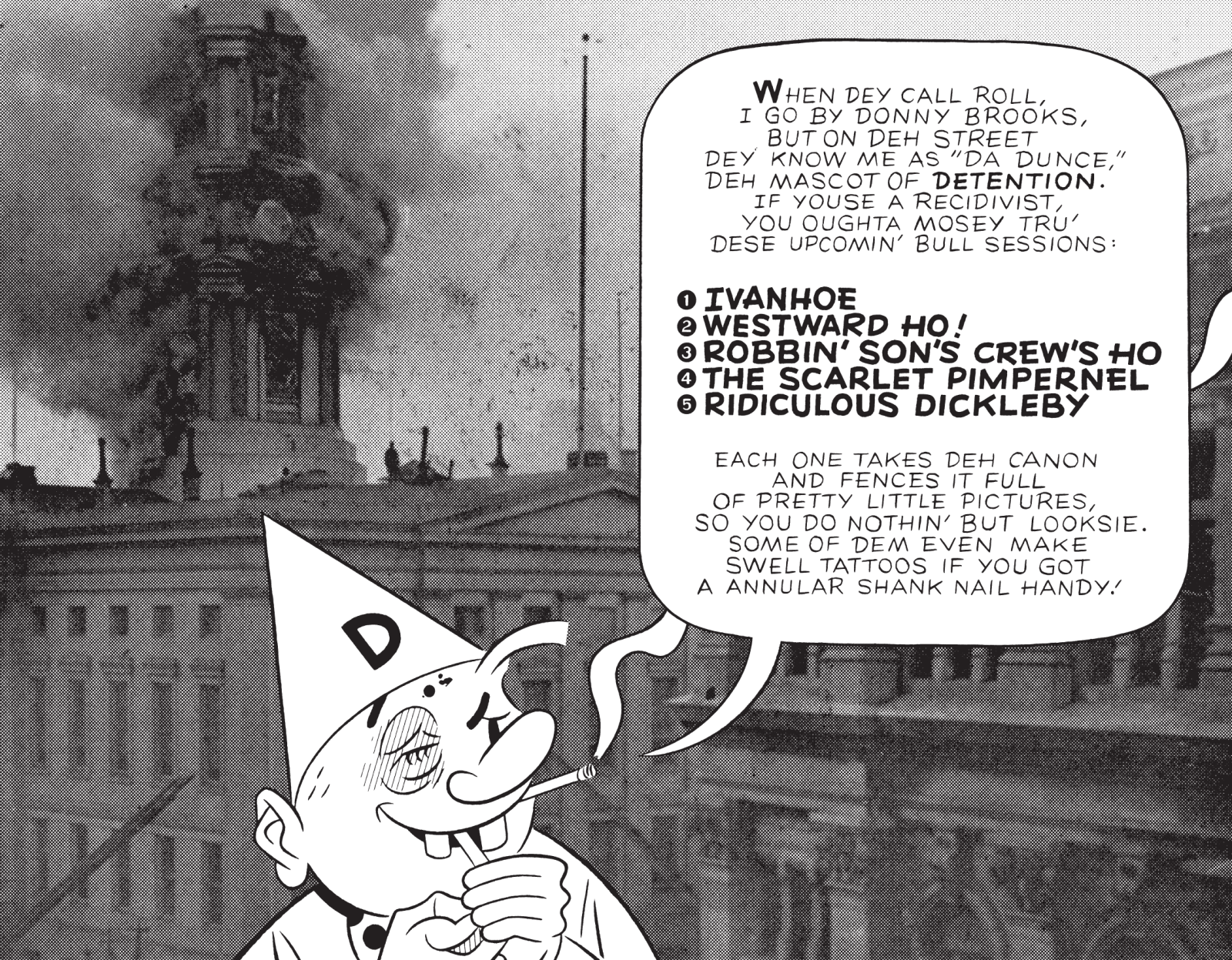

This new release from Tim Hensley is probably his most straightforward comic to date, although you'd be missing some of its charm by leaving it at that. Detention No. 2 is a sibling book to 2015's Sir Alfred No. 3—an homage to goofy celebrity branding comics of the '50s & '60s a la The Adventures of Bob Hope that also functions as a cracked biography of Alfred Hitchcock, his complexities and contradictions presented as a series of sly cartoon gags—matching the earlier work in size (13" x 10"), length (40 pages) and tongue-in-cheek packaging (there is no issue #1, any more than there is a Sir Alfred No. 1 or No. 2). But Detention has a different set of concerns: it is a timely riff on comics-style literary adaptations, ostensibly in the Classics Illustrated mold. You won't need to look far to spot the modern progeny of these 'educational' comics on the Graphic Novels shelf of your local bookstore, although, in the eyes of Detention, the whole effort might be best kept after class.

The bulk of Detention No. 2 is devoted to an adaptation of Maggie: A Girl of the Streets, a short novel by the American writer Stephen Crane, a scandalous and innovative figure best known for The Red Badge of Courage (1895). Maggie was first published privately and pseudonymously in 1893, then revised for professional publication in 1896, following its author's rise to fame. The latter year will immediately ring a bell in the head of the comic strip lifer, as 1896 was also when Joseph Pulitzer's New York World and William Randolph Hearst's New York Journal began a fierce circulation war, in which the cartoonist Richard F. Outcault notably decamped from the former to the latter with his popular character, the Yellow Kid, amidst both papers' promotion of dazzling color print processes. Notably, Crane's Maggie is set in the New York City Bowery, then a disreputable neighborhood similar to those depicted in Outcault's Hogan's Alley and other cartoon portrayals of NYC slum life.

Hensley does not adopt the form of 1890s cartooning for his adaptation, though; he employs an especially rich and detailed variation of his own style, eschewing the restless format swapping of Sir Alfred (which jumped from stacked gag strips to multi-page narratives to one-page goofs and back again) in favor of handsome seven- or eight-panel pages, with larger frames added for moments of particular note. Nor does Detention exactly resemble the Classics Illustrated of the 1950s, which adapted works like The Red Badge of Courage into pages of sharp-edged frames interspersed with round impact panels; Hensley uses rectangular frames with round edges, sometimes dropping in photographic backgrounds that appear to be collaged from multiple sources (which might also describe the whole adaptive project). The total effect is very different from the funny-but-cerebral Sir Alfred or the surreally distended John Stanley gag licks of his earlier Wally Gropius (2010); all of Hensley's comics are enjoyable, but this is the one that most directly captures the surface pleasures of the subject of its pastiche—telling an old story in a succinct and pleasurable cartooned manner—and can most be enjoyed 'on the merits' of its homage.

The closest analogue to what Hensley is doing might be Milt Gross' Sunday comics of the 1920s & '30s, laden with dialect and sometimes prone to literary parody; Gross' Baby makes a not-so-nize cameo in the Maggie adaptation as a doomed infant. Indeed, characters (or character types) from throughout the first half of comics history are deployed by Hensley as if they are actors taking the stage in period dress (fittingly, one particularly untouchable woman is a shōjo manga type in the 1950s mold of Osamu Tezuka, who explicitly treated his characters as performers inhabiting roles). This idea of 'performance' is central to what Hensley is doing with Detention. Stephen Crane's original Maggie, as a work of prose composition, intersperses a droll omniscient narration with character dialogue written as thick 'urban' patter. What Hensley does is (mostly) eliminate narrative captions from his adaptation, instead using lines from Crane's omniscient narrator as thought bubbles for the characters, while Crane's heavy dialect spills from their mouths as word balloons, like a stock company reciting Shakespeare.

Take this excerpt from the 1893 text (apparently the version Hensley is using, although he does substitute some language from the 1896 text, when spicier, which makes me suspect he is consulting editor Thomas A. Gullason's 1979 Norton Critical Edition):

One day the young man, Pete, who as a lad had smitten the Devil's Row urchin in the back of the head and put to flight the antagonists of his friend, Jimmie, strutted upon the scene. He met Jimmie one day on the street, promised to take him to a boxing match in Williamsburg, and called for him in the evening.

Maggie observed Pete.

He sat on a table in the Johnson home and dangled his checked legs with an enticing nonchalance. His hair was curled down over his forehead in an oiled bang. His rather pugged nose seemed to revolt from contact with a bristling moustache of short, wire-like hairs. His blue double-breasted coat, edged with black braid, buttoned close to a red puff tie, and his patent-leather shoes looked like murder-fitted weapons.

His mannerisms stamped him as a man who had a correct sense of his personal superiority. There was valor and contempt for circumstances in the glance of his eye. He waved his hands like a man of the world, who dismisses religion and philosophy, and says "Fudge." He had certainly seen everything and with each curl of his lip, he declared that it amounted to nothing. Maggie thought he must be a very elegant and graceful bartender.

He was telling tales to Jimmie.

Maggie watched him furtively, with half-closed eyes, lit with a vague interest.

"Hully gee! Dey makes me tired," he said. "Mos' e'ry day some farmer comes in an' tries teh run deh shop. See? But dey gits t'rowed right out! I jolt dem right out in deh street before dey knows where dey is! See?"

Hensley renders the scene like so:

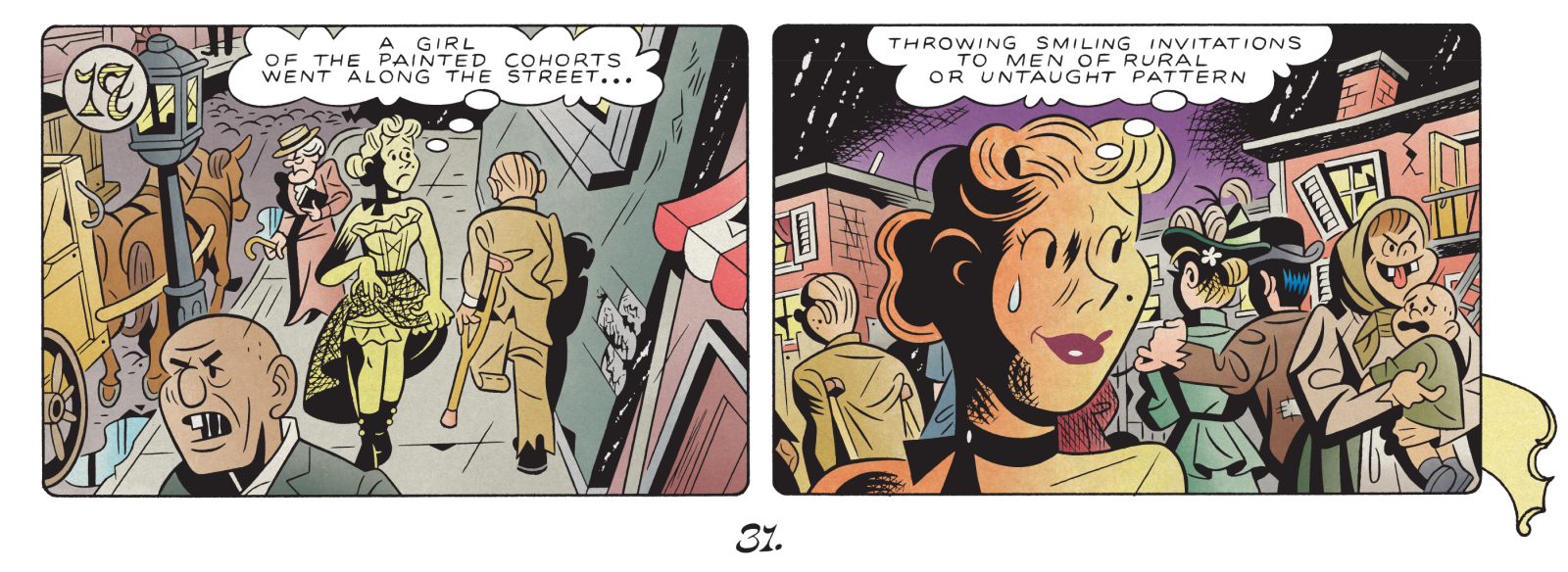

"NOT ONE WORD HAS BEEN OMITTED" barks the cover of Detention, "BUT IN FACT SEVERAL." More than just a clever means of keeping his pages free of captioned clutter, Hensley's scheme pokes fun at the traits of Crane's writing that gave him the reputation of a Naturalist. Crane's dialogue, when spoken by cartooned characters, reads as less a realistic attempt to catch the voice of the Bowery than the comedy dialects of myriad newspaper cartoonists looking to appeal to a broad city readership - especially Gross, who emerges as a sort of algebraic result from the adaptive formula Hensley is using (though Gross' particular bent Yiddish is not the pool from which Crane had sipped, and Hensley's very thought-over art does not capture the lightness and agility of Gross' own drawing). Similarly, Crane's Maggie is fatalistic; a girl "blossomed in a mud puddle," the heroine pins all hope of joy on a romance with a local barkeep, but the young man's class aspirations and the brutish resentments of Maggie's family conspire to ruin her happiness. She ends up selling sex on the streets, a doom-laden chapter in the Crane text that Hensley transforms into fine wordless character action, as Maggie tragicomically attempts to proposition customers:

This sort of thing used to be called a burlesque: a travesty on highfaluting themes. On a yet higher level, Hensley is lampooning efforts at capturing prose literature in cartoon terms. To see a tiny grimacing boy in suspenders staggering away from a street fight thinking "This is degradation for one who aims to be a vague blood soldier of sublime license," is very funny and self-evidently absurd. Maggie's ultimate fate, having met "a huge fat man in torn and greasy garments," is rendered in a quite symbolic manner in Crane's prose, which a drawn adaptation would be gravely challenged to match:

At their feet the river appeared a deathly black hue. Some hidden factory sent up a yellow glare, that lit for a moment the waters lapping oilily against timbers. The varied sounds of life, made joyous by distance and seeming unapproachableness, came faintly and died away to a silence.

I will not reveal how Hensley details Maggie's demise, but it involves a slapstick device so startling that, reader, I gasped.

But I don't think Hensley means this as some wan commentary on the failures of the comics form, or a revanchist call to cleanse the scene of hints of sophistication. What I get from my time in Detention is an argument for comics as a medium of ambiguous beauty. What I mean is: in placing Crane's narration in the minds of the characters, their thought bubbles, Hensley affords them a self-awareness that struggles to articulate itself over the din of their circumstances, which is a type of dignity. This is natural to comics. The first thing you would notice in a prose story like Maggie is the narration. The first thing you notice in a comic is the drawing, even if you're mostly the type to privilege the writing. It is the drawing that forms the stuff of the comic's world, and Hensley's way of balancing the drawing with Crane's clashing letters is to place these paper dolls in poignant internal struggle; and does that not honor the motive of the text, in departing from it?

There are some other pieces in Detention No. 2. There is an additional Stephen Crane adaption on the back cover, a version of his 1898 cowboy short story "The Bride Comes to Yellow Sky" done in the one-page wordless style of Hensley's adaptation of Hitchcock's I Confess from Sir Alfred. There is a rather formalistic short comics biography of Crane himself, and a funny peek into the Classics Illustrated offices. And then, there is a pair of one-page comics starring Jacob Riis, the famous muckraker and author of How the Other Half Lives, who was a contemporary of Crane's in documenting New York City poverty. Hensley's comics, however, focus on Riis' role in the popularization of flash photography - which, of course, would eventually reduce the role of cartoons and illustrations in newspapers. But this is not a eulogy.

This is a farce, with Riis terrifying his subjects with pistol lamps, blinding himself with reflective pans, and generally being a well-intentioned menace. Under Hensley's pen, the evolution of photography is celebrated on the level of cartooning: inexact, funny, winsome, chaotic. Pride in misbehavior.