On August 11, six days before his 90th birthday, French artist Jean-Jacques Sempé peacefully passed away. He was one of the world's best-known cartoonists, that pen behind the classic Le Petit Nicolas. He also gave the New Yorker magazine more covers–112–than anyone in its history. His last cartoon appeared in Paris Match the week before he died.

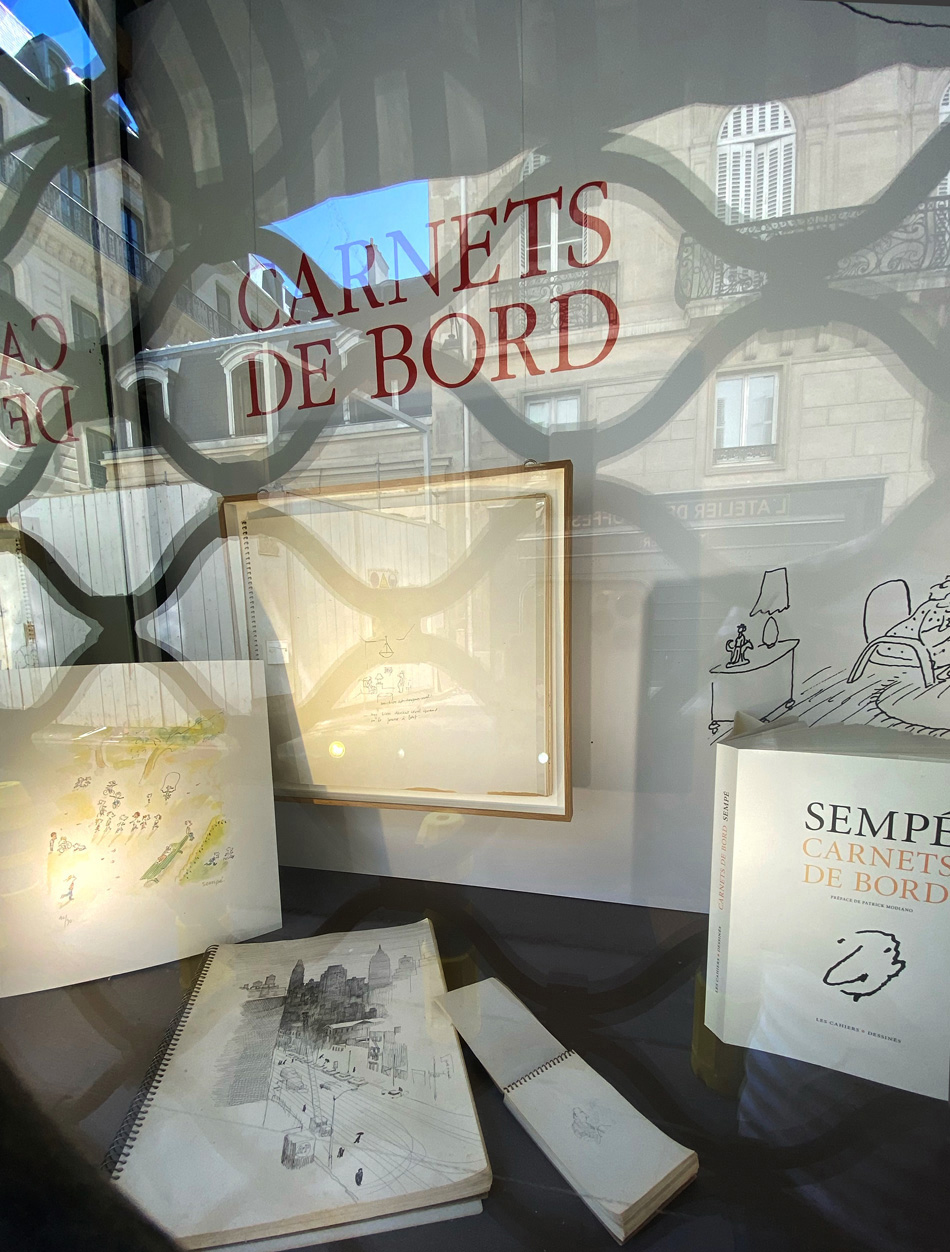

The day before his loss was announced, I chanced to pass the gallery run by his wife. It was blindingly hot, the street was deserted, and, like the rest of Paris, everything was closed. But there were some of Sempé's sketchbooks in the window. Their pages almost sang with his delicate lines, which looked as clean and luminous as fine steel wire. This was the line Président Macron praised as an embodiment of "jazz and tender irony… the elegance of a light touch that nothing can escape."

Jean-Jacques Sempé was born at Pessac, near Bordeaux, in 1932. He was the illegitimate son of a secretary and her boss - a fact he discovered only in his 20s. At first, he was placed with a rough foster family. But then his mother married and brought "Jeannot" home. There, he found a chaos that would shape the rest of his life. His stepfather, Edmond Sempé, bicycled door-to-door selling bottles of pickles and preserves. But every sale he made was celebrated in local bars.

Sempé grew up in the world behind those black-and-white photos of "vintage" France. It was a world where, until 1936, you got smoke breaks instead of a vacation. One where, until 1956, school kids had rations of wine, beer and cider - for nourishment. A world where, in summer, "vacation colonies" bused kids like him to the country. The hope was that some fresh air might stave off TB.

Life at home was also far from tranquil. "My mother," Sempé told his biographer, "was eternally hounding my father about his job." There were nonstop arguments and endless debts, which caused the family to move again and again. Jean-Jacques had a stepbrother and a half-sister, but, as the eldest, felt he should exert control. Yet if he tried to, either parent might land a punch. The household's tension gave him nervous tics and a stutter.

Sempé had only one escape: school. There, he became known for pranks and troublemaking. He survived, he always said, because of the radio. From the age of five, he stayed glued to it, losing himself in everything he heard. Through the airwaves he discovered not just jazz but popular song, theatre - and manners. "I was impressed by how people sounded, by the timbre of their voices and their politeness." From favorites like the suave actor Louis Jouvet, he absorbed a new, different way of speaking: deferential, charming and discreet. He retained it for the rest of his life.

There were no books at home. But, through the neighbors and his mother's friends, Sempé discovered the novels of Maurice Leblanc ("the French Conan Doyle"), the weekly L’Illustration (launched in 1843 to edify the working class) and magazines with titles like Confidences ("Secrets"). Confidences told him that, to improve your spelling, it was important to read "anything you can, even a map." So he did and, until his death, Sempé was proud he rarely misspelled a word.

Sempé revealed his rough start in life in the 2011 book Enfances ("Childhoods"). His mother's harsh treatment and her tirades, he said, had filled his early years with misery and shame. "Yes, my childhood was vile and dreary," he told Paris Match the last time they spoke, "and it scarred me in a way I wish it hadn't. But that was a different era, one when a lot of people slapped their kids around…. My poor parents always did the best they could; I've never spent a moment resenting them."

Expelled from school at 14, Sempé failed applications for the French railway and the postal service. Instead, he found regional work - selling tooth-powder, working at a vacation colony, delivering samples of wine on a bicycle. To escape, he lied about his age and joined the army.

Sempé discovered drawing late in his teens. What he really wanted was to become a footballer or a musician. "Instead, I had to draw them. Because, in my world, it was far easier to find some paper and a pencil than a piano." By the age of 19, his cartoons were appearing in local papers. He signed them "DRO", the way he thought "draw" would probably look in French.

When the army posted him to Paris, he loved it. "I found Parisians so animated, so exuberant," he said at the 2011 exhibition Sempé, un peu de Paris et d'ailleurs ("Sempé, a bit of Paris and beyond"). "Everything about the city enchanted me: the metro, the bus, the fever of the crowd… in cafés and tabacs, in shops, there was genuine warmth." During the last interview he gave, however, he mourned a change. "Life now is far too fast; it's become restless and brutal."

While still in uniform, Sempé began to haunt agencies and art departments. He sold some sketches to Le Rire and France Dimanche and then to a Belgian culture weekly, Le Moustique ("Mosquito"). He also got his very first work from Paris Match, the start of a partnership that ended only with his death.

By 1954, Sempé's work was making Le Moustique's cover, and he delivered art to the syndication service World Press. One of their employees was René Goscinny. As well as drawing, the 27-year old wrote ad copy and scripted cartoon strips. Goscinny was six years older, but, like Sempé, he was struggling. "René was the first friend I made in Paris", Sempé said, "by which I mean he was my first-ever friend."

Each had a solitary childhood behind him. The Jewish Goscinny had grown up in Buenos Aires, hearing by mail how uncles and aunts died in Auschwitz. Then, when a heart attack killed his father, he tried working in Manhattan - where he almost starved. Sempé himself had dreamed about New York; he felt he knew it from the New Yorker magazine. But Manhattan, Goscinny informed him, was more than a temple of jazz and graphic humor. Jean-Jacques, in his turn, schooled the expat about French life. René couldn't hear enough about school pranks, football and charity camp.

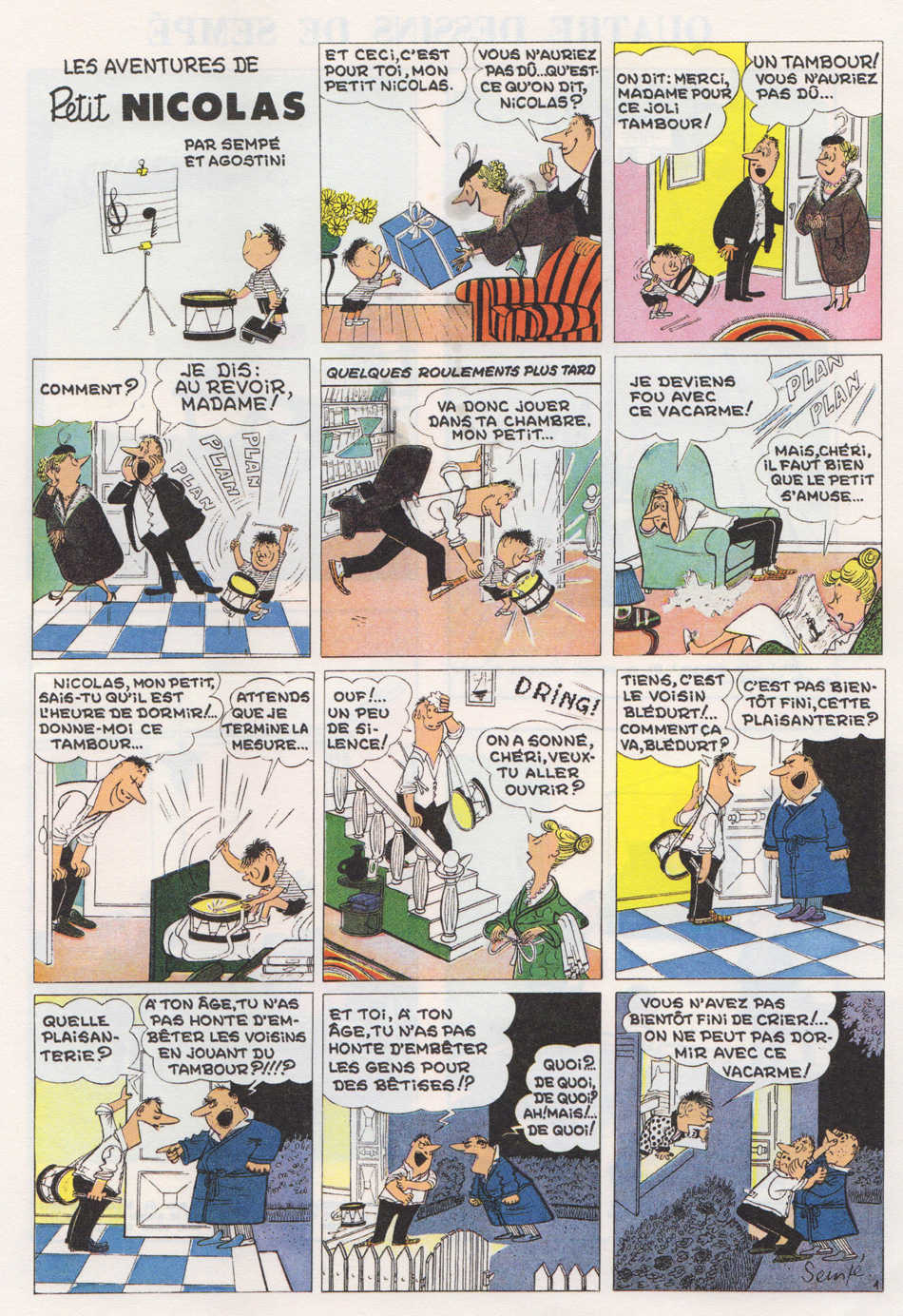

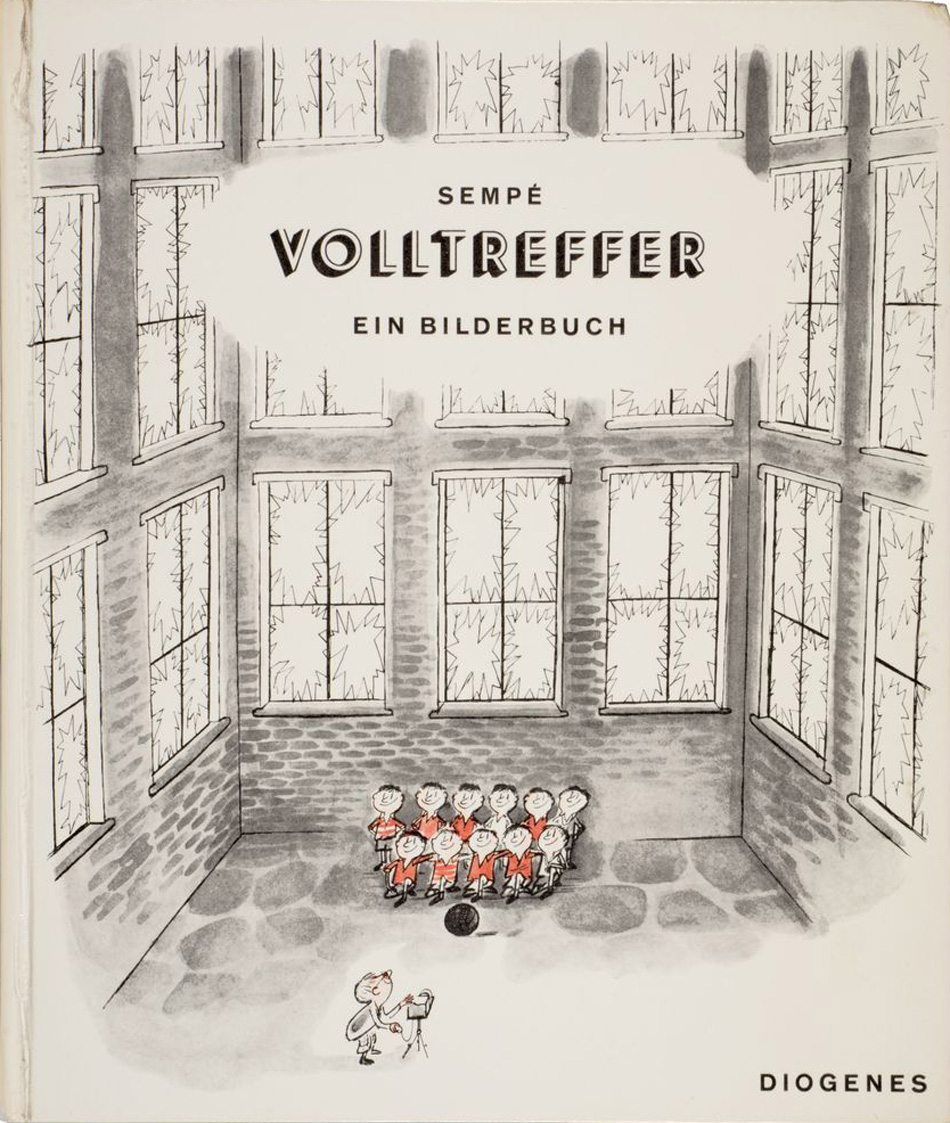

In 1954, for Le Moustique, Sempé sketched an impish boy rolling in the mud. The paper proposed he make the boy into a character. On his way to meet the editor about it, Sempé passed an ad for the Nicolas wine stores. "I handed in my sketches," he told José-Louis Bocquet, "saying 'Call it Les Aventures de Nicolas… or Le Petit Nicolas.' I had drawn the character like I drew every kid. Except that, this time, I had added a sailor shirt."

Sempé had never liked or read bandes déssinées, but he could hardly pay the rent on his top-floor room. So, when Le Moustique offered him a contract, he gratefully agreed. "René knew all about comics, so I called him. Luckily for me, he agreed to write it." The pair's strip ran 28 times in Le Moustique, between 1956 and 1958. But Sempé always hated the format; he always saw himself as "a single-frame cartoonist." So each moved on and Nicolas was abandoned.

Then, in 1959, Sud-Ouest called Sempé - who was now one of their regulars. They had a children's issue to fill for Easter. He and René decided to revive Nicolas, but not as a strip. Instead, they created a text wound around mute cartoons. Readers loved the page, and the paper asked for more. The pair went on producing tales for seven years. Le Petit Nicolas appeared not just in Sud-Ouest but in Pilote, a new publication Goscinny was co-editing. In 1960, Denoël began to issue their stories as books.

Sixty-plus years later, Le Petit Nicolas has sold gazillions, appeared in 45 languages and become a string of films. But it was hardly an overnight success. Sempé cajoled Paris Match into plugging its debut - but they refused to even name the book's co-author. Although Goscinny had begun Astérix, he was still far from famous. "I was distraught," Sempé told Bocquet, "but they still refused. They said 'OK, he's your pal and we get it. But none of us know him.' That first Nicolas only book sold 28 copies." But then its authors appeared on television, to discuss what kids ought to read. Sales took off - and they've never stopped.

Out of opposed and far-from-perfect childhoods, the odd couple had given birth to a classic. They aimed for what Goscinny called "a world kids would recognize and adults would remember… a universal world where anyone would like to live." He wrote the stories from a child's point of view, in his own pastiche of childish speech. As the tales boomerang between art and text, they shape a sphere that seems placid and petit-bourgeois. Its children quarrel, tell fibs and play modest tricks. But they decrypt not just their school and playground. Also involved are their perceptions of authority: adult parents, neighbors, teachers - and their relationships.

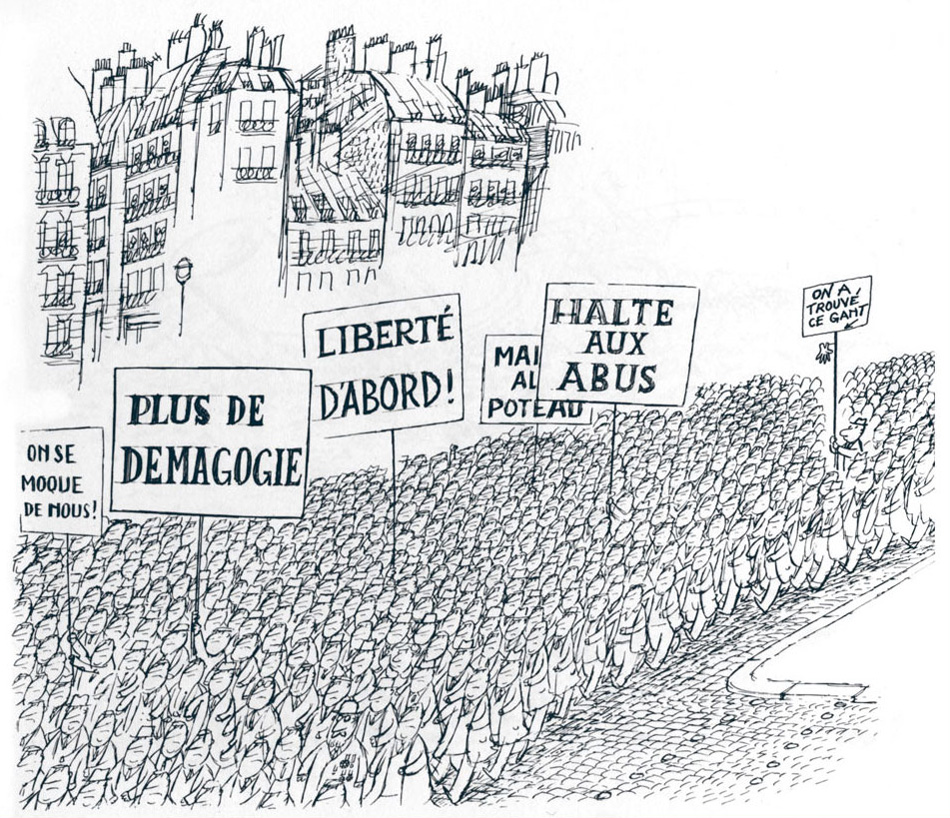

The Nicolas stories have a timeless, suspended tone, like that of fables. But their insouciance is less of their own era than of the year between 1936 and 1937, when the Popular Front ran France. This short and radical Front Populaire is, one historian writes, "fondly remembered for the fervor of its hopes and the human scale of its social ambitions." The art it generated has a deep humanism, one you can sense in artists like writers Eugène Dabit (Hôtel du Nord), poet Jacques Prévert (Paroles) and filmmakers Marcel Carné (Les Enfants du Paradis), René Clair (À nous la liberté) and Jean Renoir (Le Crime de Monsieur Lange).

Concrete factors underwrote their sanguine views: the Matignon Accords of 1936 agreed a 40-hour work week and paid vacations. But optimism spread more widely through the airwaves. At the moment Sempé discovered it, radio was reaching 20 million listeners. It filled French ears with upbeat tunes and stars he loved: Duke Ellington, Ray Ventura, Jean Gabin and Paul Misraki. Radio brightened homes that still used oil lamps, drew their water from distant pumps and spent entire days on laundry.

Sempé's grandfather, whom he loved, was a Communist ("I marched with him, my puny fist in the air"). But it was radio, not politics, that shaped him - first, during the 1930s, with music and theatre; then, during World War II, with de Gaulle's Radio Londres. From them, Sempé said, "I learned everything. But, more than anything else, they taught elegance. Elegance is really what matters most to me; an elegance of feelings, manners and gestures."

All this helped create the world of Petit Nicolas. But the story was constructed and not remembered. "No-one," Sempé once told Radio France, "portrays a childhood by 'remaining a child'. That idea of 'eternal innocence' is wrong; no-one relives his childhood. What you do is reassemble, work with tiny elements, maybe brighten a memory. But it's always an exercise in D-I-Y."

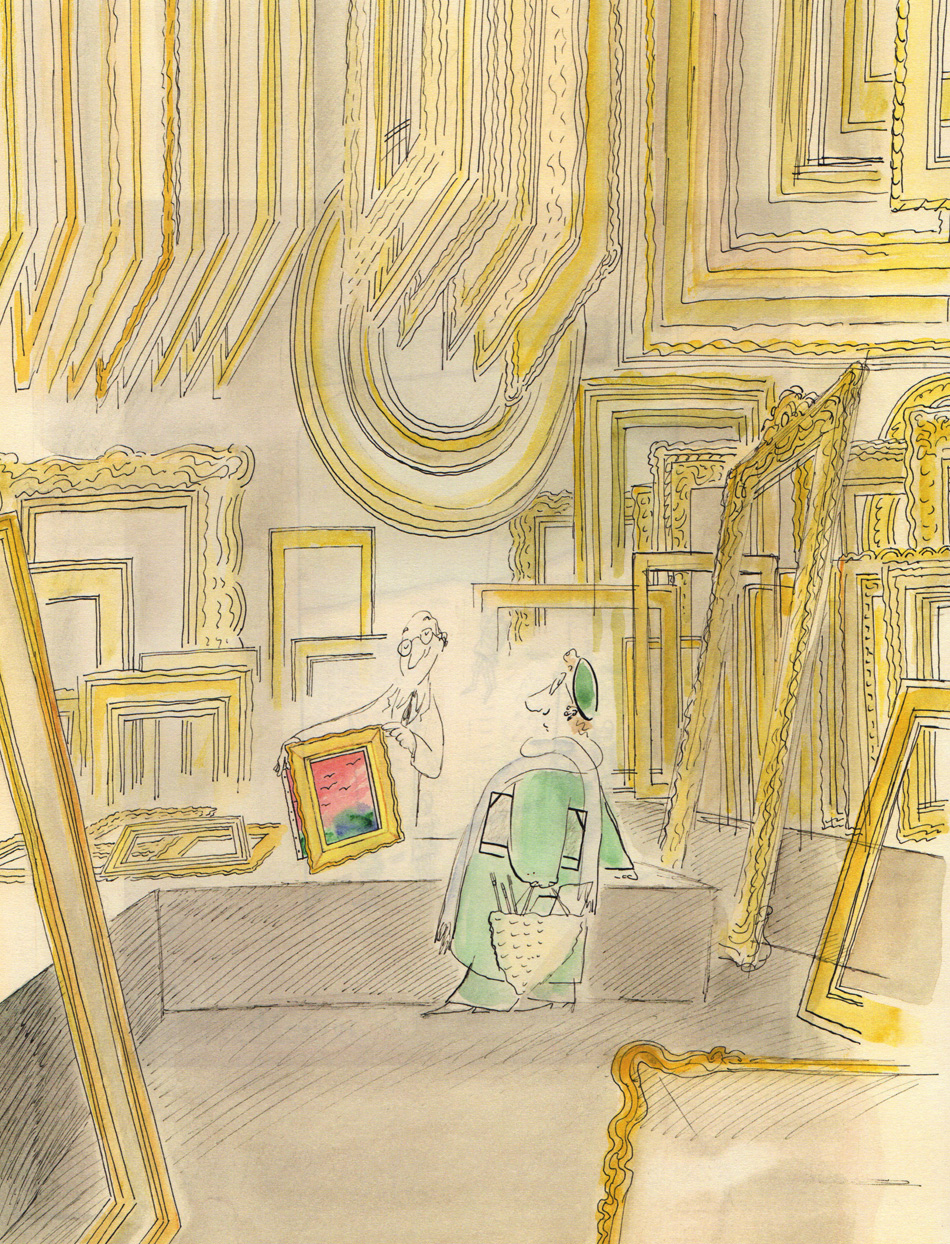

Sempé's eye is one of comic history's most acute. But his French characters are never stereotypes. In fact, from the moment he first put pen to paper, he demonstrated one dominant skill. The comedy of manners he could spin from line and space is the equal of Molière and Proust.

"I don't really think I have a style," he told his friend Marc Lecarpentier. "I think I just have tics. But, then, maybe it's the tics that make a style. Marcel Proust, who I really love, certainly had his own! Let's just say I'm always trying to polish my tics …"

The France Sempé captures may be modern, but the sociability and rites he shows are not. They are fundamentals in a national fabric woven through centuries, a complex built out of ritual and thought. All of it aims to make existence into an art. That's what Sempé heard in Paul Misraki's songs and it's that–not stripes and berets–which makes his art so deeply French. As Francis Marmande put it in Le Monde this week: "Sempé was a cartoonist. But only a cartoonist? No. He had the talent to analyze and make us laugh, he could excite us and show us things we never noticed. He was able to change our point of view… and he gave us just as much food for thought as Georges Perec, Pierre Bourdieu or Roland Barthes. The laughs were a bonus."

From the 1950s, Sempé's work was everywhere, from Paris Match to posters, France Dimanche to Esquire. Since 1962, Denoël has published a book by him every year. They are bestsellers with titles like Rien n'est simple ("Nothing Is Easy"), Tout se complique ("Things Get Complicated") or Sauve qui peut ("Every Man for Himself").

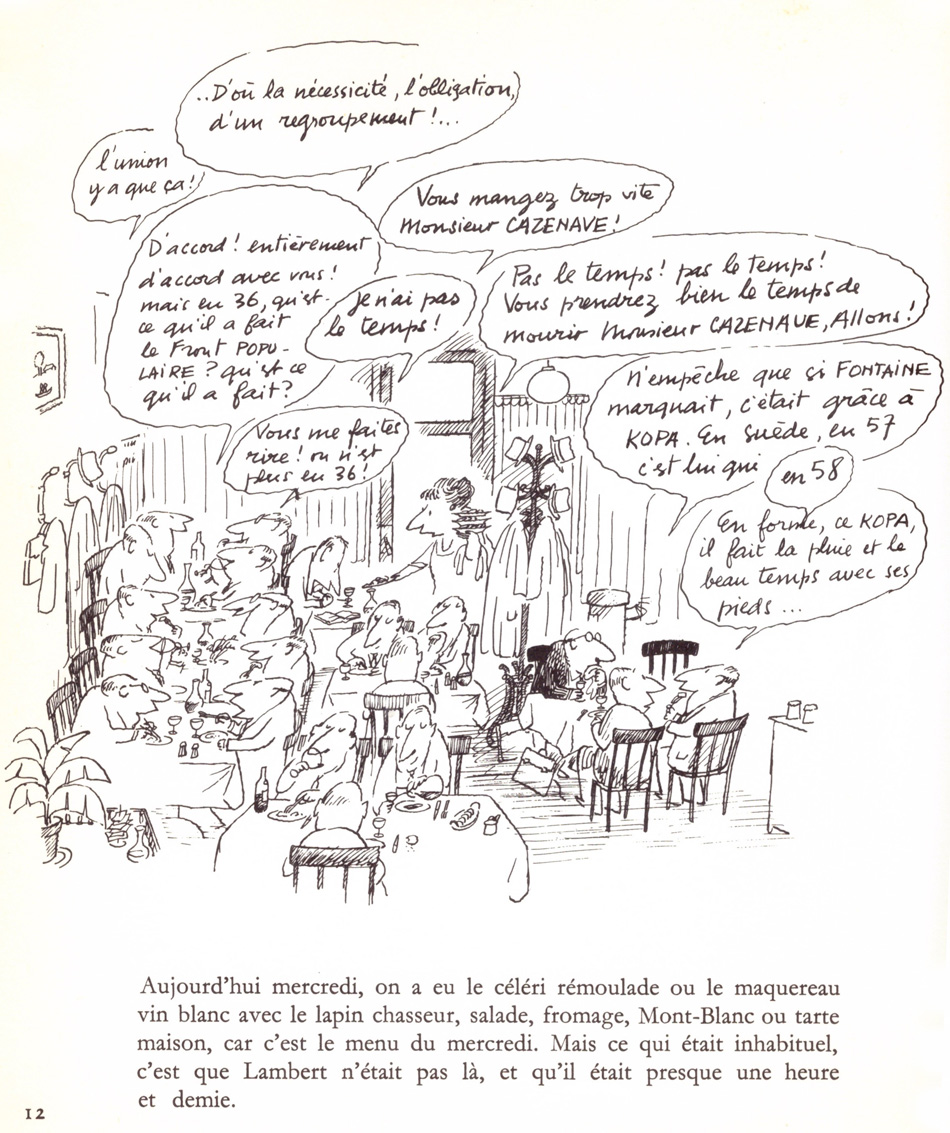

Sempé's own favorite was Monsieur Lambert. Published in 1965, it concerns a tiny bistro. There, the same crowd comes to lunch every day, where they argue about politics and football. They depend upon each other and the menu (drawn as the endpapers of the book). Then, one of them, Monsieur Lambert, alters his habits. Instead of noon, he arrives at 1:30, then at 1:34, then, at almost 2:00. When he refuses his first course, thoughts run wild. The wrangles over Jean Gabin and football cease and speculation turns to Lambert's assumed secret.

The reader never learns why his schedule changed. But the move frees everyone's imagination until, abruptly, custom reasserts itself. Monsieur Lambert, says the novelist Benoît Duteurtre, "is as void of special effects and drama as life itself. But its dialogue outdoes Harold Pinter."

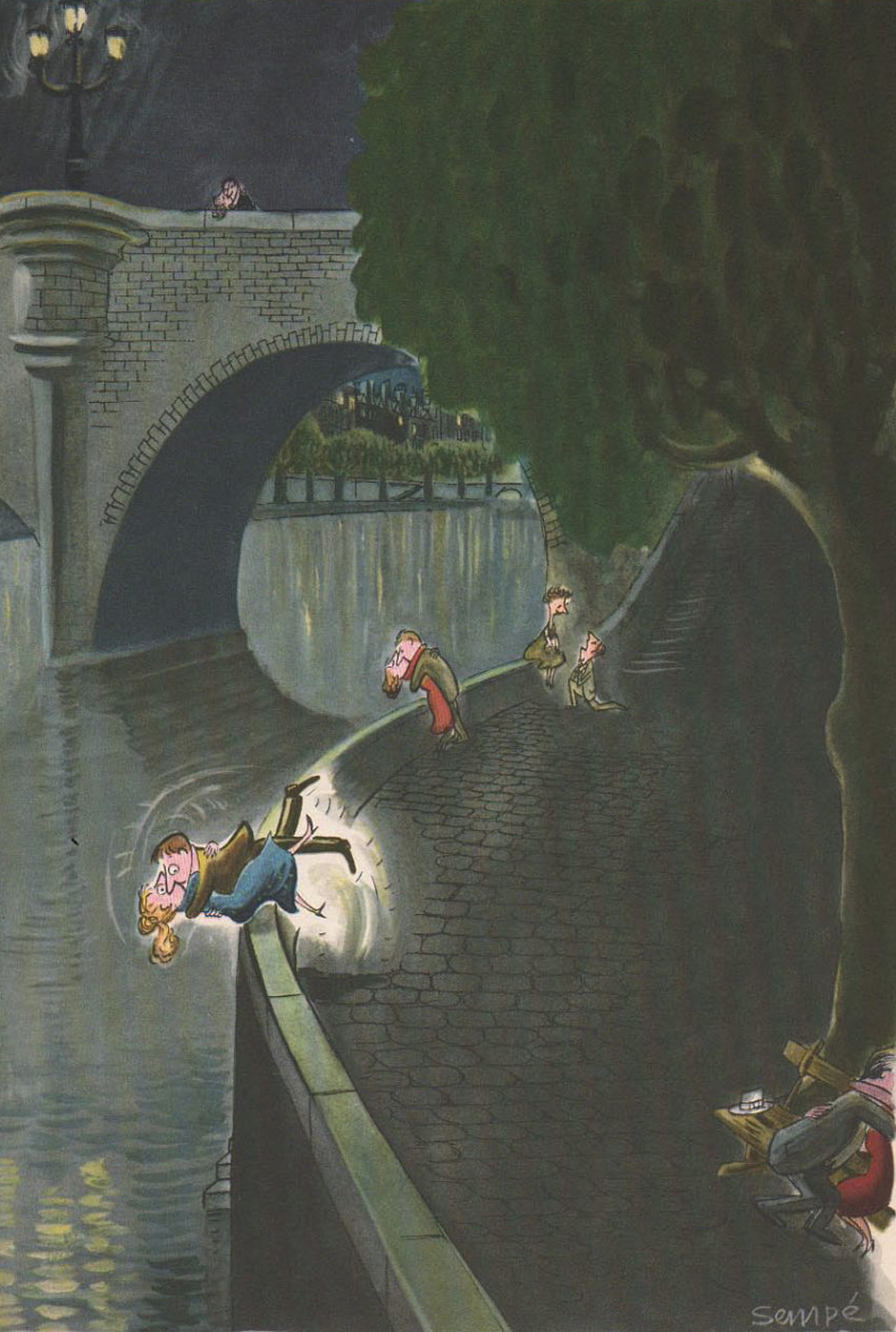

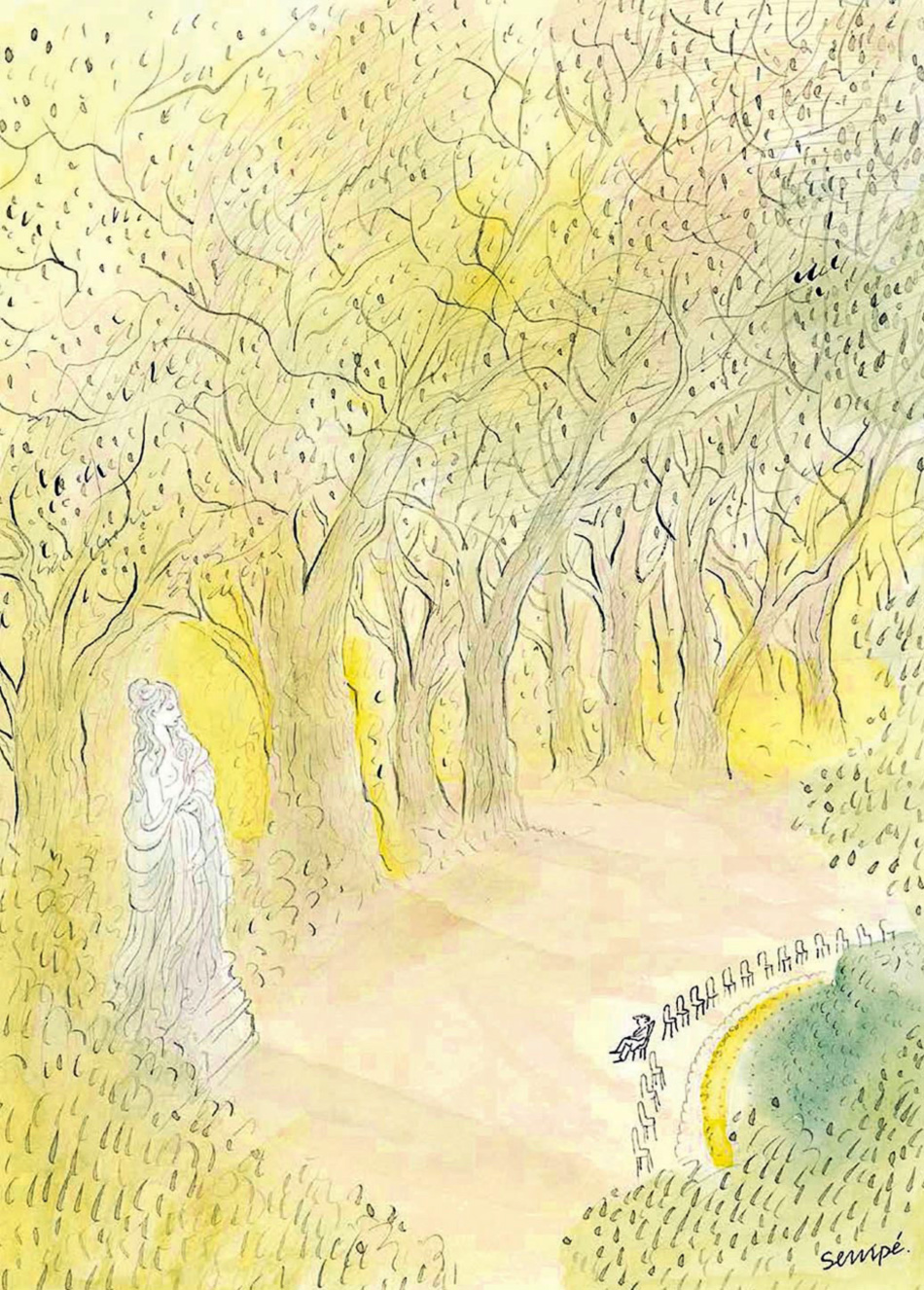

Sempé lived in Paris' Montparnasse, a quartier of artists since Modigliani and Eugène Atget. He drew at a huge table six floors above the street, facing a window with a panoramic view. For years, he cycled, strolled and loafed in local parks - especially the Jardin du Luxembourg. He worked on outsize boards, spending days on details. A single drawing might take a month.

His obsession with work, Sempé said, defined his life. But he was also married three times: to painter Christine Courtois (their son, Nicolas Joël, died in 2020); illustrator Mette Ivers (their daughter, Inga Sempé, is a designer); and, in 2017, to his agent, Martine Gossieaux. His path was showered with honors: the French state made him a Commander of Arts and Letters, the Angoulême Festival gave him their Fauve d'Honneur, and the French mint asked him to design new coins. He also collaborated with literary stars like the Nobel Prize winner Patrick Modiano, and Patrick Süskind, author of Perfume.

In America, too, Sempé remains a legend. This began in 1978, when New Yorker journalist Jane Kramer visited Paris. She brought one of Sempé's books back to Manhattan - where she showed it to her editor, William Shawn. Shawn wrote the artist, saying: "Do what you like for us and do it whenever you want." It was Sempé's dream come true, his longed-for passport to the city of Saul Steinberg. His first New Yorker cover appeared on August 14, 1978.

Finding what he wanted, once again, took Sempé time. "At first, I was totally lost. I understood nothing, which caused enormous stress. The first few drawings I sent them were less astute observations of reality than exposures of my own confusion." Little by little, however, the magazine became a perfect vitrine for his "little moments".

The New Yorker's French recruit–known as "JJ"–never spoke English well. But it helped, he said, that to control his stutter he had always spoken slowly. Sempé also scorned communicating by phone or fax; he preferred to show up in person. Such trips soon made Manhattan fully part of his art. He saw New York as "exciting and far less grey than Paris." He also cycled its boroughs, often in the company of cartoonist Edward Koren. The New Yorker's art director, Françoise Mouly, who handled Sempé's art for 30 years, said: "All our readers in America know his work and that's not something I could say of all our artists."

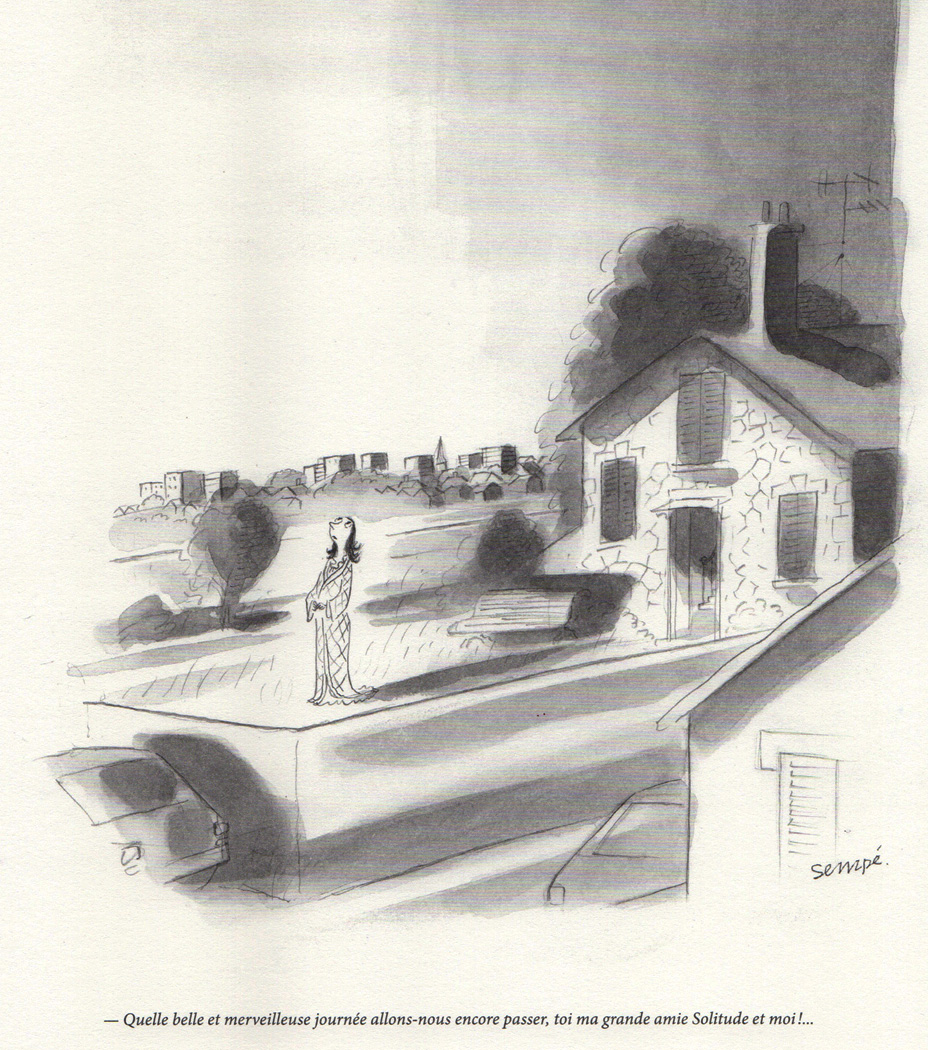

Sempé's New Yorker fame is a delicious thing - a culture immune to irony idolizing one of its greats. It came about through his true gentleness, his real love for Sunday painters and fanatical cyclists, weary musicians and hopeful ballerinas. His art was never sentimental but always compassionate; Sempé offers the viewer hope in a frame.

He was first inspired by artists now often forgotten. They include satirists like Jean Bosc (1924-1973), Jean Bernard-Aldebert (1909-1974) and "Chaval" (Yvan Le Louarn, 1915-1968). Sempé also loved poster great Raymond Savignac (1907-2002). He knew Chaval, who killed himself at 52; Bosc and Sauvignac were close friends. All of them taught him to favor pure, conceptual lines. But they also transmitted another age, one where discretion was less a grace than an essential. Chaval, who drew for a pro-Nazi paper, once said "I never took any public stance… I was just lonely." But Aldebart went to the camps for mocking Hitler. He recorded the experience in an album, Chemin de Croix. But, said Sempé: "He never spoke about it. After that, all he wanted was to laugh."

Sempé too willed himself towards the positive, just as he willed himself to speak as well as Louis Jouvet. In 2007, he suffered a stroke and spent many of his recent years in a wheelchair. But his right arm remained unaffected, so, as soon as he could, he went back to work. The only difficulties he would broach concerned his art.

Nothing about that, he said, ever got easier. "You can't even start unless you have a good idea, which can take you an hour or a month… or more. Only then can you draw or try to find a text. It's a long process and it's sometimes hellish. But it's also fascinating. You have to shadow a caption, tail it like a detective. Then you start to sand it down, more and more, until it works."

"People tell me things like 'Haussmann only built his balconies on two floors, the fifth and second ones.' But I put them anywhere. Because what you see, what's apparent, is not the truth. When you draw in close, the truth is in the atmosphere. So suggest truth, it's atmosphere you need… ambiance and suggestion."

Sempé leaves behind countless albums, posters and catalogues (a new book, Sempé en Amérique, is due in October). But one of his finest works appeared last year. It was published by the Buchet-Chastel label Les Cahiers déssinés, run by artist-writer Frédéric Pajak.

Entitled Carnets de bord (roughly, "Logbooks"), it holds 237 pages of sketches. Few have captions and many are drawn with pencil. Some are so light they almost seem to fly off the page. But all are wondrous. They epitomize that "atmosphere" which made Sempé so beloved, his line that–as Patrick Modiano writes in his preface–has the ability to escape gravity. Whether it contains suggestions or full mise-en-scène, each page captures Sempé's special eloquence, the way he spoke through what he withheld.

Jean-Jacques Sempé is represented by the Galerie Martine Gossieaux, and his Carnets de bord is published by Les Cahiers déssinés; Sempé en Amerique comes out October 12 from Denoël/Éditions Martine Goussieaux.