Artist Scott Finch’s creative journey is guided by shamanic visions. He has devoured the writings of Carl Jung, Joseph Campbell, and numerous books on myth and legend. His early work, focusing on painting, provides a discipline that has enriched his more recent work in comics. We’ve shared a couple of conversations that make clear to me that his approach to his art is not so far removed from a shaman receiving visions. Talking about his first graphic novel, A Little World Made Cunningly (2013), Finch described a series of images appearing to him as if out of a dream. It was tied to the mythos he’s so familiar with but in a way that he could call his own. That same process informs his new graphic novel, the recently released, The Domesticated Afterlife.

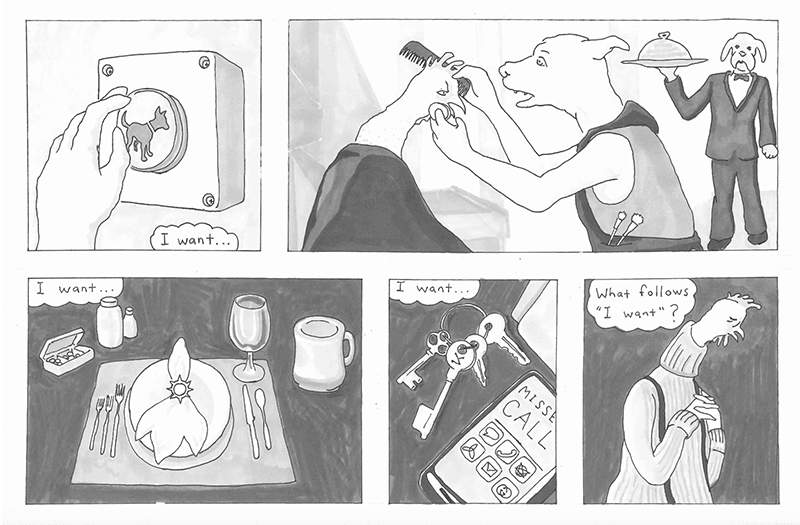

This new book is the story of a world within a world, a trope in myth that Finch could embrace and make his own. It revolves around a set of characters trapped inside a world where roles are very rigid: dogs are servants; cats are supervisors; and chickens are overlords. The story begins with one of the regulars from this inner world, a small demonic-looking dog, venturing out to lure a wild wolf from the outer world. This wolf, Enaid, strikes a devil’s bargain and allows himself to be “domesticated” in order to secure steady food and shelter. Once inside, Enaid finds himself a wage slave, a cog in a perpetual system, forgetting his origins with each passing day. Perhaps his only hope is Ci, a fellow dog co-worker he has befriended. But as much as these two may resist, even plot an escape, the system in place is there to beat them down into further submission. Enaid and Ci are lost while constantly reminded of their place among the lower working class.

An unfortunate mishap lands Enaid and Ci deep in the bowels of the factory ship they toil within. The two had been placed on an assignment working on a retail sales floor that put them into direct contact with the chickens, the prime consumers in this hierarchy. One chicken, addled by all the options of what to buy, confronts Enaid out of fevered frustration. This triggers Ci into a violent reaction. He loses any self-control he had clung to in his humanoid slave state and reverts to a real dog who promptly pounces upon the rooster and tears his head off. This incident leads the two to a trip to their inevitable reconditioning in the hunger hull. You can’t go much deeper down the rabbit hole once you’ve reached the hunger hull. Ah, and once the slave is more compliant, it’s up a few steps and back to work.

Finch draws with a light line that buoys his fanciful vision. His characters, while simple, are full of expression. His backgrounds tend to be simple too but can vary in complexity. Finch consistently finds interesting ways to fill the page, whether through composition, patterning or shading with watercolors. He uses a rectangular format that gives his work more of a comic strip, or movie screen, vibe which he uses to his advantage. Facing pages throughout relate well to each other. For instance, there’s a series of pages where Ci’s legs are stretched to infinity that is quite unusual. Another fine example has the cat office manager Maishan dreaming of a grand escape in a car that is perpetually thwarted by a great wheel they must cross that repeatedly has him and his friends crash and drown while a dim-witted demi-god looks on.

Finch has his characters go inside their heads into further inner worlds. Enaid, for instance, gets lost ticking a rant about himself thinking about himself thinking. And he has his characters go to worlds well beyond anything they have yet encountered through interdimensional travel. Through it all, these otherworldly excursions point right back to all of us as we grapple with heightened social inequalities. Finch offers a fable for our times with offbeat humor and wisdom gleaned from centuries of myth and legend. It’s when we realize how little we are seeing that we open ourselves up to revealing the bigger picture. Finch, by adroit and skillful handling of his subject, steers a narrative brimming with big ideas on the eternal seeking of enlightenment. He knows when to bring in a touch of humor, when to hold back a bit, and how to get to those concise and crisp utterances that attempt to offer up some notions on the meaning of life.

When I asked Finch to explain how he developed the characters in his book, he told me that they went back to his childhood. That notion stuck with me: child-like images of our earliest friends; innocent animals, the first strangers we invite into our lives, our earliest connections. All of this primordial goo filtered through the lens of the collective consciousness storytelling tradition. What Finch ends up with is right in line with some of our best comics imbued with that special weird and gentle power. These are comics from creators that embrace the arcane and make it their own like Daria Tessler and Jesse Moynihan. This is work rich in ambiguity and mystery that emerges over a long period of trial and error. It’s not necessarily the most technically accurate and polished artwork. But it must ring true. Because, if it doesn’t, then the spell is broken. And that’s what Finch is doing here. He has cast a spell. He has lit a candle. And he's kept the flame burning.