In the final month of 2021, we invited our contributors to hold forth on the best comics of the year, "however you might define that." What follows is perilously close to 22,000 words on that very broad topic, in a variety of forms—lists, commentaries, jeremiads—with no firm system of qualification or quantification. Rather, you are surrendered to the desires of our writers, whose names you are encouraged to click for helpful links to all their contributions to the site. Use this page as a checklist, a shopping guide, an amusement, a blood pressure spike - and rest assured, there is something here that will prove wonderful, that you have never seen before.

- The Editors

* * *

I find myself reading fewer and fewer comics, unable to spend money on what seems like endless boring rehashes or the new waves of middlebrow life stories and boring visual literary fiction. But I did read some few comics this year that excited or amused, in no particular order:

Crisis Zone by Simon Hanselmann (Fantagraphics): I often find Hanselman's Megg, Mogg, and Owl comics a little too much, so I did not read this as it was being serialized, but when I finally picked up this collection I was wonderfully surprised, the world has risen to that level of too much to make these comics perfect for the times, moving, hilarious, and biting, all encompassed in a seemingly endless series of square panels filled with great cartooning.

Prayer to Saint Therese by Alabaster Pizzo (Perfectly Acceptable): Another comic that first appeared on that annoying photo site; I came to it, somehow, having no experience with Pizzo's work, and this won me over. Across mostly four-panel square pages, with simple rendering and single-color printing that changes with the location/time, Pizzo tells a brief near-future fictional autobiography. Like Crisis Zone, it feels very much of the time, despite taking place out of the time.

The Complete Crepax 6: Dangerous Liaisons by Guido Crepax, translated by Micol Beltramini (Fantagraphics): A perennial favorite for me, I await the new releases of this series, like no other (see my review of vol. 4). This is peak Crepax: visually stunning, narratively engaging.

Lipstick Traces by Trevor Alixopulos (self-published): I have whole anthologies and comics magazines I bought just because there was an Alixopulos comic in them, so this collection of his stories was a surprise and a delight. Something about his bendy down-and-out hipsters wandering in the night really works for me. His art is fresh, angular, often abstract and minimal yet clearly showing a debt to old styles of cartooning.

Ostende by Dominique Goblet (FRMK): This showed up from Europe after I started working on this list, but almost by its very existence I knew it would make whatever list for whatever year it arrived. Goblet is one of those too-rare artists who comes to comics with a sensibility and taste that is not just based around other comics. This book is filled with large beautiful painted images and on a first read I don't feel like I totally (or even mostly) understand, which means I can go back multiple times and get more from it each time.

Blocks by Oliver East (Rolling Stock): Already reviewed this year in full.

Thirteen comics in no particular order, minus the most recent Margo Maloo book, which I haven’t read yet but have no doubt would make the list. I could write about all the books I read this year that I found annoying and overrated and coarse, things that I didn’t want to read in a year where I felt like my skin kept getting rubbed off just when it was regrowing, but I also don’t want to yuck y’all’s yum. So here are some yums of mine that you might like too.

Tunnels (Drawn & Quarterly): Rutu Modan (translated by Ishai Mishory) is working at the absolute top of her game, getting better with each book she puts out. The only problem is that she doesn’t put them out fast enough because she clearly labors over the complex, gorgeously-drawn images and the speedy, intense, propulsive scripts. Quite possibly the book of the year but one that I don’t want to spoil here by talking about it too much. I fell in love within two pages and never stopped greedily reading until I was, sadly, done.

The Secret to Superhuman Strength (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt): I was extremely skeptical about this, given how much I disliked Are You My Mother?, but it remedies the weaknesses of that book (too serious, too theoretical, too wordy, excessively organized) and ends up being an enjoyable tour through Alison Bechdel’s life as exemplified by her pursuit of various athletic endeavors and her hunt for enlightenment. Where Are You My Mother? couldn’t get out of the creator’s head, this book examines that weakness without falling into a spiral of reflection that’s boring to the reader.

Let's Not Talk Anymore (Drawn & Quarterly): A surprise makes for the best kind of comic, to me. Weng Pixin’s focused, carefully painted book sneaked up on me and wound its way around my heart and my head. Her brushstrokes are beautiful, her color palette is unafraid, and her understanding of the relationships between generations of women is subtle and emotionally intelligent.

Oksi (Levine Querido): This Finnish book (translated by Silja-Maaria Aronpuro) was also a surprise, more Angela Carter than Emily Carroll, a dark fairy tale about the violence of love and family, rendered in inky watercolors with color that stands out like inlay. Mari Ahokoivu is one to watch for the future for sure, an artist who’s unafraid to wade into a frozen swamp of mud and blood and fire and show how beauty and danger can coexist.

Aster and the Mixed-Up Magic (Random House Graphic): A total charmer of an all-ages comic (translated by Anne Smith & Owen Smith), slam-packed with Easter eggs in the corners and background, a neatly-arranged story keyed to the seasons of the year, and the most fun and cute character design around. Thom Pico and Karensac have other books out in France already, and I cannot wait for them to be translated into English so that my kids and I can read them. If you’re looking for the next Hilda, but a little goofier, this is it.

My Begging Chart (Drawn & Quarterly): Meditative stuff from Keiler Roberts that is also often drily funny about fatigue and parenting in a way that no one else is really doing. She’s done this before, but she keeps doing it so well. It’s like Porcellino but with more detail on the page and more acid in the perspective.

Red Rock Baby Candy (Fantagraphics): Shira Spector’s book is a flower garden on roller skates, an explosion of cosmetics, an elaborate piece of autobiographical embroidery about love and death and family. It’s a LOT of look, but it’s winning in its desire to throw absolutely everything onto the page.

Thirsty Mermaids(Simon & Schuster): This isn’t quite as good as Kat Leyh’s previous book, Snapdragon, but it’s still one of the best books of the year, albeit one likely to be overlooked in indie comics circles because it came from Simon & Schuster. Watching Leyh exercise her fluid, intuitive grasp of comics vocabulary is like seeing an amazing athlete do her thing. She busts through rules with élan and delight, and manages to make it work each time.

Katie the Catsitter (Penguin Random House): Colleen AF Venable doesn’t get enough credit for what a good writer she is, probably because she doesn’t also draw her books, but her warm and clever scripts have fueled a lot of wonderful things, including this new middle-grades book about a kid who turns to cat sitting to earn money for summer camp. Stephanie Yue’s drawings are just as great, with distinctive characters and nice panel design.

Factory Summers (Drawn & Quarterly): Okay, fine, some comics by dudes. Guy Delisle’s memoir of his teenage summers working in a paper factory (translated by Helge Dascher & Rob Aspinall) is sharp and well-observed on matters like labor and class and the ways that men relate to each other when women aren’t around. He likes to take things apart and see how they work, and this book does that in a variety of contexts, including the inner workings of the artist himself.

Rebecca and Lucie in the Case of the Missing Neighbor (Drawn & Quarterly): I’ve read most of Pascal Girard’s other comics and enjoyed them well enough, but this one (translated by Aleshia Jensen) feels like a step up, with a protagonist who isn’t just a rejiggered version of the author. It’s billed as a postpartum murder mystery, but the latter is the MacGuffin for the former rather than the other way around. It’s a light book, but not a slight one, with a surprising amount of emotional depth.

Billionaires: The Lives of the Rich and Powerful (Drawn & Quarterly): Darryl Cunningham’s book about the Koch brothers, Rupert Murdoch and Jeff Bezos uses simple iconography and easily could have been a one-thing-after-another nonfiction comic (a lot of them fall into this category). Instead, it’s pointed and smart in its critiques as well as often quite funny. Capitalism is a virus, and this book does a marvelous job laying out why.

The Nib: I can’t imagine this daily comics email (and, now, occasional print magazine focusing on a different theme each time, sent to my physical mailbox for a mere $5 a month!) slipping off my best-of list, where it’s been ensconced for the past few years. Funny, enraging, and marvelously varied, it teaches me things and it exposes me to new cartoonists all the time. Imagine an alternative newsweekly’s comics section, but make it every weekday and a lot more and a lot better.

Well, that was another really weird year. Checking my selection for last year I note that I was worried that Brexit and rising shipping fees would impact my reading, and they definitely did (Goodreads informs me that my physical comics reading dropped by 12.5% compared to 2020), but there was also the fact that our lockdown in England lasted until midsummer, and even after that we had supply issues and a whole load of distro chaos going on, so it was another 365 24/7 of mostly buying books I knew I'd enjoy.

Peow's victory lap before they close up shop continued with Ex.Mag 03, edited by Wren McDonald, a series of anthologies for which I was an easy mark anyways, because genre nonsense keeps me going, but weird dark fantasy ended up being something of a theme for my year, which also included regular microdosing of Nick Edwards' Kingly and the Ninkugel arc of Benjamin Marra's What We Mean By Yesterday.

Also on that genre note, after Kentaro Miura sadly passed away in spring of this year, and my various social media timelines were awash with imagery from Berserk (translated by Duane Johnson) (Dark Horse), I finally pulled the trigger and went all in on Guts and Co., reading a volume a week until I reach the point I am at now - waiting on the new advertised-in-the-broadsheets volume to drop. It's gnarly to the extreme, the pacing is all over the shop, the Cool Guy Line beats hit like a large hunk of iron, and I will probably re-read it on the regular when I'm as exhausted as I have been all year, as it's invigorating - the scratches on the page as frenzied and transformative as its hero's suit of armor in later volumes.

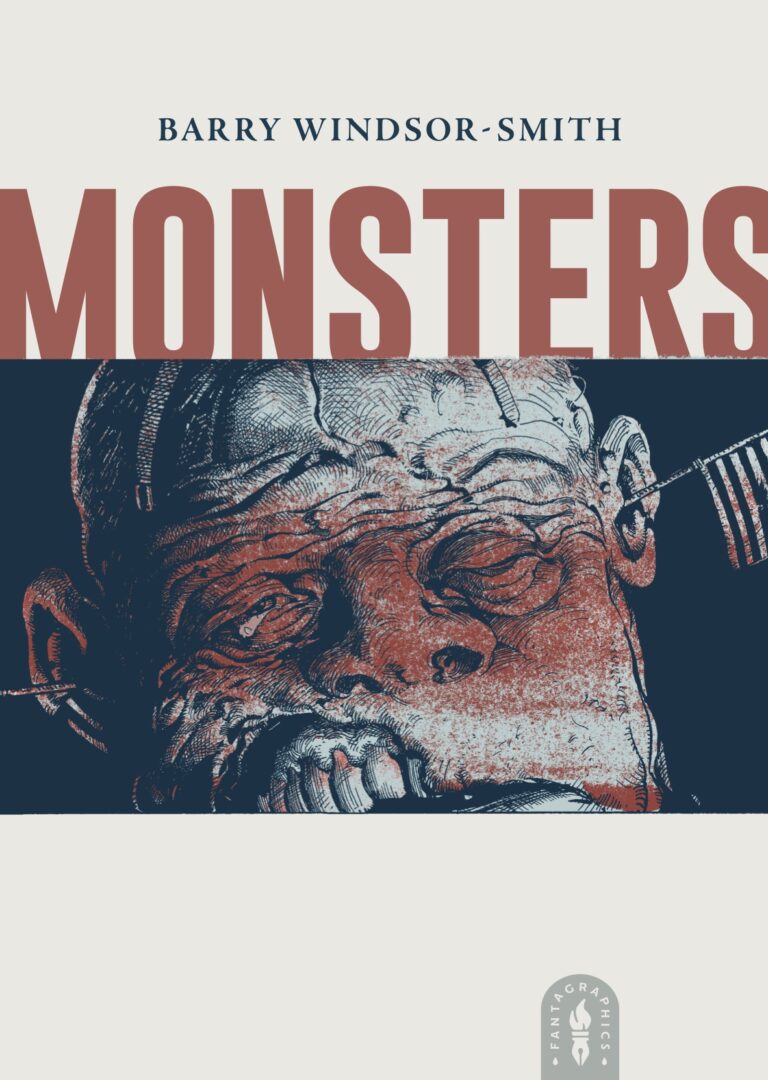

Similarly so, the sheer amount of effort that clearly went into Barry Windsor-Smith's Monsters (Fantagraphics) is formidable, and I enjoyed the generational horror that unfolded between its meticulously detailed lines quite a bit. However, it is totally bizarre to me that it took so long to hit market, and that it did so right when Marvel have been dining out on the critical success of Al Ewing, Joe Bennett (since blacklisted for a number of sins) et al. on The Immortal Hulk in the same window - somewhat rightfully so, as it's a solidly enjoyable title in terms of modern superhero fare, but it really does riff on a number of the same themes.

My social surrogates for the year both came in the form of classic comics in new collections with Shary Flenniken's Trots and Bonnie (New York Review Comics) and Gary Panter's Jimbo: Adventures in Paradise (New York Review Comics) providing some enjoyable anarchy, as I spent a good chunk of time once again watching the seasons change through a window (world's smallest violin playing, &c &c).

Other than the above, the rest of what popped into my head when thinking about titles that were memorable from the year involved navigating the great manga shortage of 2021: Naoki Urasawa's Asadora! (translated by John Werry) (VIZ) is meandering in a way that is comfortingly reminiscent of a BBC tea-time serial; Tatsuki Fujimoto's Chainsaw Man (translated by Amanda Haley) (VIZ) consistently makes me bark laughter during even the most protracted depressive episode; likewise for Tetsuo Hara's and Buronson's Fist of the North Star (translated by Joe Yamazaki) (VIZ); and Masumura Jūshichi's Children of Mu-Town (translated by rkp) has me excited for what Glacier Bay Books has coming in 2022.

There's plenty I want to catch up on that I missed out on through not attending shows and book launches, which would be my usual resupply missions, Breakdown Press' and ShortBox's 2021 output especially, but there will be time enough for that in Pandemic Year Three.

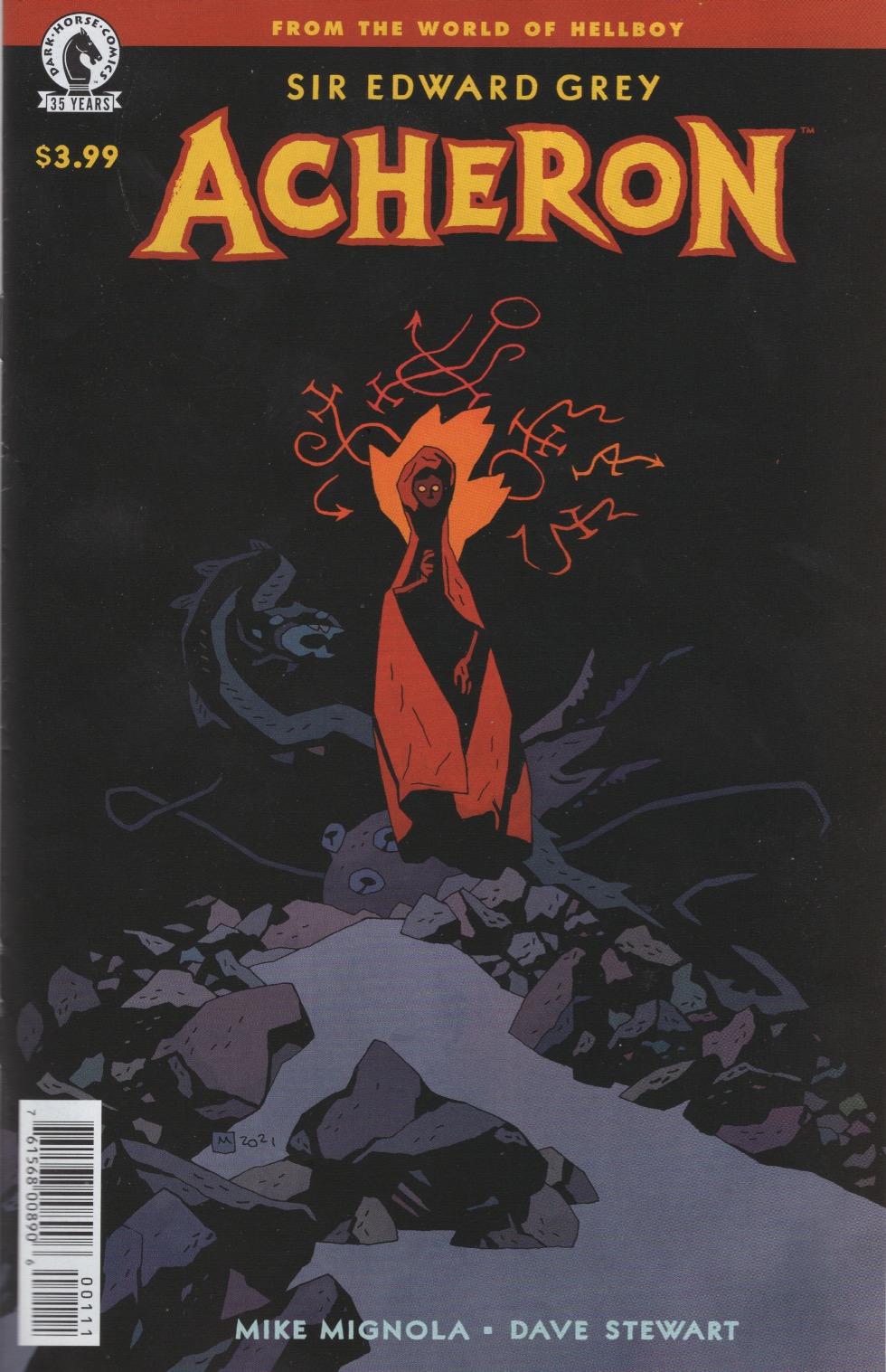

I love lists, so I can’t help but count down to number one this year using my proprietary formula of comic book quality based on a variety of sensory factors multiplied how much I want to hold the comics in my hands again and absorb their essence. Just outside my top 10—these would be my honorable mentions for the year—are Sir Edward Grey: Acheron by Mike Mignola, Dave Stewart & Clem Robins (Dark Horse), Love and Rockets by Jaime and Gilbert Hernandez (Fantagraphics), Spider-Man: Spider’s Shadow by Chip Zdarsky, Pasqual Ferry & Matt Hollingsworth (Marvel), Wonder Woman: Historia by Kelly Sue DeConnick, Phil Jimenez, Hi-Fi, Arif Prianto, Romulo Fajardo, Jr. & Clayton Cowles (DC Comics), and Night Hunters by Dave Baker and Alexis Ziritt (Floating World Comics). Those are all some great-looking comics, worthy of your consideration.

Here’s my top 10 for the year:

10. Catwoman: Lonely City by Cliff Chiang (DC Comics). I always wanted to see Cliff Chiang writing his own stuff because his art is by far the best part of anything he’s ever been involved with. This oversized hey-it’s-Black-Label DC series looks amazing and has humor and heart as an ex-con Catwoman, fresh out of prison, prepares to pull off a big heist. I think it’s only 4 issues so it’s halfway complete, but the first half is a delight. Large-format Cliff Chiang with words by Cliff Chiang is what you need for the holidays and beyond.

9. One Eight Hundred Ghosts by G. Davis Cathcart (self-published). Another heist comic, this one is the opposite of Lonely City in almost every way: small, hand-printed, new-to-the-scene artist, bonkers plot, and an aesthetic that’s beautifully repellant. It’s like if an instructional manual from 1982 gained sentience and birthed a riso-printed zine of itself, with ferocious confidence.

8. Alanzo Sneak by Nate Garcia (self-published). Flipping through this magazine-sized comic, your first thought is probably something like “is this like a Pete Bagge western or something?” It is not. Well, it is a western, of a sort. There are guys with cowboy hats. Horses. Trouble. But Nate Garcia is vicious and hilarious and this comic surprised me more than once. He has a loose-limbed quality reminiscent of Bagge, but Garcia is his own thing and I hope to see a lot more from him.

7. Boy Maximortal #3 by Rick Veitch (King Hell/Sun Comics). Volume 3 of this ongoing King Hell Heroica project popped up via Veitch’s self-publishing arm of Amazon a few weeks before Christmas, and it’s a volume I will revisit. The main thread of the narrative—largely about consumerism and grift and superhero comics in previous volumes—is devoted to the more transcendent and/or horrifying aspects of the supernatural title character in this book. As a slice of entertainment, it’s a wonderful package, with a host of hard-to-find or never-before-seen Veitch comics from an earlier era (even his childhood) backing up the main story. Veitch is one of the great masters of comics and he’ll always give you something unsettling.

6. The Human Target by Tom King, Greg Smallwood & Clayton Cowles (DC Comics). Another DC Black Label title for the discerning Wednesday warrior. Do comics even come out on Wednesdays anymore? I’ve lost track during the pandemic, and instead I get my comics in batches during my resource runs under the cover of night. In these bleak times, The Human Target is here for us, with Smallwood’s lifestyle illustration artwork and King’s fondness for the Giffen-era Justice League. This is a pure pop comic, inhaling the fumes of a Raymond Chandler movie adaptation while it dances to a jazzy soundtrack.

5. Echolands by J.H. Williams III, W. Haden Blackman, Dave Stewart & Todd Klein (Image). This ambitious, mythic series is a riff on a “grownup” Red Riding Hood tale that looks like it exploded between the panels of Williams’s Promethea and Batman: The Black Glove pages. Williams does that thing he’s the best in the world at here: drawing characters in the style of various eras and various artists, with all of these characters coexisting in a fantastic landscape. I was sold on the series from the first issue, but once the Jack Kirby/Captain Victory-inspired pirate king shows up for a few scenes, I was committed for life.

4. Heaven No Hell by Michael DeForge (Drawn & Quarterly). This collection of a recent batch of DeForge’s continually amazing comics is a guidebook to the beautiful and horrible and absurd. I think the best way to read a DeForge story is to sit down and read it, twice, then go for a walk for no less than 20 minutes and contemplate the mysteries of the world and the art of comics, then maybe shovel some snow or do the dishes, then sit down and read the next one. These comics are so pure, I don’t know what well he has tapped into, but it’s important to give each story its own space to seep into your brain.

3. The Green Lantern: Season Two by Grant Morrison, Liam Sharp & Steve Wands (DC Comics). The final two issues of this multi-year experiment in pretending to tell a Green Lantern story while actually giving Liam Sharp a playground to exhume his artistic influences like a necromancer with a grudge are oblique and unsettling. Morrison alludes to a superhero continuity that has only sort-of happened, thrusting Hal Jordan and friends into a faux-medieval space landscape where they confront supergods and supervillains that are somehow the distilled essence of John Broome's and Gardner Fox’s id. The finale of the series is Sharp’s dangerous gallery, though, and he requires your attention.

2. Birth of the Bat by Josh Simmons (The Mansion Press). I haven’t stopped thinking about every page of this comic since I picked it up in the late summer. It haunts me and reminds me that it exists. It lurks and lingers. I thought the comic was funny when I read through it the first time. Now it follows me everywhere I go, inside my mind. Josh Simmons is magic. But the kind you can’t show your mom.

1. Copra by Michel Fiffe (Copra Press). The conclusion of the Ochizon Saga was released from Michel Fiffe’s dining room this year, and the comic book series that has been my favorite thing in the comic book world over the past decade has not disappointed me yet. This is Fiffe doing the Fourth World colliding with his Ostrander and Ditko playground, self-published for pure comics power. Every issue of Copra is an artifact, and each deserves a hermetically sealed display case, but what I do with each issue is throw it in a pile with a bunch of yellowing, unbagged '80s newsprint and Baxter comics, where it feels most at home.

As is my custom, I did top ten lists for the year broken down into six different categories on my Four Color Apocalypse blog, but for those who (understandably, I might add) don't wish to wade through all of that, I'll spotlight the following as being worthy of special, standout status:

I Never Promised You a Rose Garden (Fantagraphics) - Mannie Murphy's lyrical history of Portland blends the personal and political into one sprawling, visually poetic narrative that is quite literally impossible to shake. An auteur work in the truest sense, this is a requiem for too many dreams to count and arguably the most heartfelt polemic ever attempted in the history of this beleaguered medium of ours.

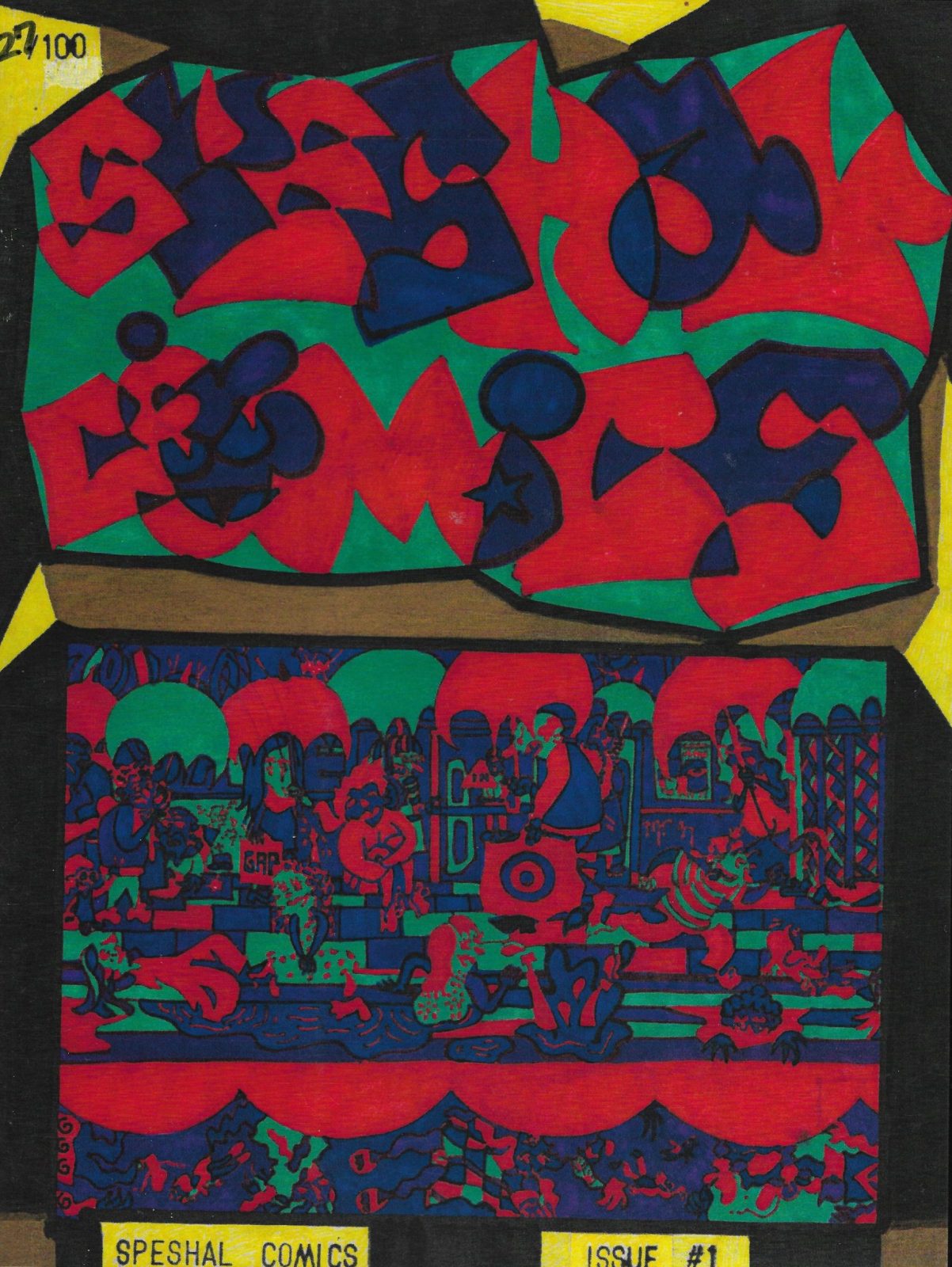

Tinfoil Comix/Speshal Comics (Dead Crow) - Floyd Tangeman's anthologies are pushing comics forward in a way not seen since Kramers 4. Featuring a rotating group of mainstays you've more than likely never heard of before but are certain to again, this is grassroots art with purpose and passion, held together by dint of sheer perseverance. Nearly every page feels like something these cartoonists were COMPELLED to create, and the energy and vitality surging from these books could probably power a small city. These aren't just "required" reading - they're NECESSARY reading. And if you don't know the difference, you will once you've read them.

Crashpad (Fantagraphics) - Gary Panter's love letter to the underground embraces its influences while eschewing nostalgia for its own sake, and as a result we have a work that refrains from wallowing in the past but still cleaves to the more noble aspects of its temperament. Perhaps the most out-and-out idealistic of Panter's works to date, any charges of naïveté one may be tempted to level against it are quashed by the sheer sincerity that so obviously went into every line, both drawn and written.

The Domesticated Afterlife (Antenna) - Scott Finch arrives "fully formed" with this graphic novel over a decade in the making, and the effort shows in every panel. A conceptual exploration of the mysteries at the core of existence itself with a dash of anarcho-primitivist philosophy at the margins, to call this "unlike anything else" is to sell it FAR too short - in point of fact, it's unlike anything else ever CONVCEIVED, much less committed to paper. The most ambitious comic of the year, at the very least, perhaps of the last five to ten.

Trots and Bonnie (New York Review Comics) - It was an up-and-down year in terms of production quality for NYRC, but any marks in the ledger against them for not necessarily taking the care they should have with Jimbo: Adventures in Paradise are more than made up for by the meticulous restoration work they did on this comprehensive collection of Shary Flenniken's trailblazing National Lampoon strips. Still, at the end of the day any historical/archival volume is only as strong as the content it presents, and Flenniken's comics remain as brilliantly unnerving and tragicomically resonant as ever. One of the most important comics of its time, perhaps even of ALL time, FINALLY gets its due.

Enigma: The Definitive Edition (Dark Horse/Berger Books) - Speaking of classics from the past, while we may have hoped for a bit more from what's sure to be the final iteration of Peter Milligan's and Duncan Fegredo's quintessential take on postmodern superheroics and the meaning of identity (secret and otherwise), having this unsung classic from Vertigo's early years back in print in a more comprehensive package than longtime fans of the series ever could have hoped for just a few short years ago fills me with such unbridled "fannish" joy that I won't quibble over what could have been, and will instead simply be grateful for what is. Existence is absurd, sure - but a comic like this is all it takes to remind us of how grand that absurdity can be.

From Granada to Cordoba (Fantagraphics) - On the other side of the coin, sometimes there's nothing like a relentlessly downward existential spiral to make you appreciate how good you've got it, and the doomed-from-jump everyman protagonist of Pier Dola's darker-than-darkly-comic OGN has it bad enough to make ANYONE feel lucky in comparison. The peace of the grave is literally all this guy has to look forward to, yet this is anything but an interminable slog, packed to the gills as it is with some of the most forceful, confident, and truly SINGULAR cartooning you'll ever lay eyes on. Life's a bitch, then you die, but if you read this book a good few times over the course of your existence, I daresay you can't call that existence a wasted one.

Dog Biscuits (self-published via Lulu) - Wait, hold up - wasn't Alex Graham's daily "pandemic comic" the fashionable choice for best comic of the year in 2020? It sure was, and it was my own favorite as well, but here's the thing: reading it in finished, collected form between two covers is an entirely different experience to consuming it piecemeal as you scroll through a screen, and really makes a person realize what a Herculean task Graham was able to achieve by weaving the entire deformed tapestry of the weirdest year on record into one story while still keeping her characters and their all-too-human (even if they're animals) foibles and frailties front and center. The most achingly real comic in a generation, produced with here-and-now urgency from first page to last, is a feat we aren't likely to see again anytime soon - and while the circumstances that led to this comic's creation have abated somewhat, its relevance unquestionably hasn't. A pivotal, transformative work in the history and evolution of the medium itself.

“Screwed the Plug” series by Derek M. Ballard (self-published on Instagram)

Ballard was already a top-tier artist, so it’s truly amazing to see someone of his caliber get even better and post that evolution concurrently on social media. I interviewed Ballard about these comics here.

Francis Bacon by E.A. Bethea (Domino Books)

Earlier this year, I wrote that this book was “an instant cult classic, if not the best book of the year.” I stand by that. My full review is here.

Trots and Bonnie by Sherry Flenniken (New York Review Comics)

This collection of hilarious, sinister, perfect comics has been my reprint Holy Grail for years. Thank you to NYRC for finally, finally making it happen. Now let’s see a collection of M.K. Brown’s Aunt Mary’s Kitchen!

Crisis Zone by Simon Hanselmann (Fantagraphics)

The online version made into my “Best of” list last year, but holding it all in your hands is a whole new experience. Taking a comic strip off Instagram while maintaining the pacing and joke structure, making it even more readable on paper, is a considerable achievement in itself.

(Cover Not Final) by Max Huffman (AdHouse Books)

I’ve recommended this comic to people in real life more than any other book this past year. Both the way Huffman draws and writes is so damn funny and idiosyncratic. He’s one of the best cartoonists alive.

Stone Fruit by Lee Lai (Fantagraphics)

The only hardcover dramatic “literary” graphic novel that brought the heat this year. Lai makes every single character vulnerable in their own unique way, but what I found most impressive is that the child in this book talks and acts like a real kid, which is hard to find in any form of media.

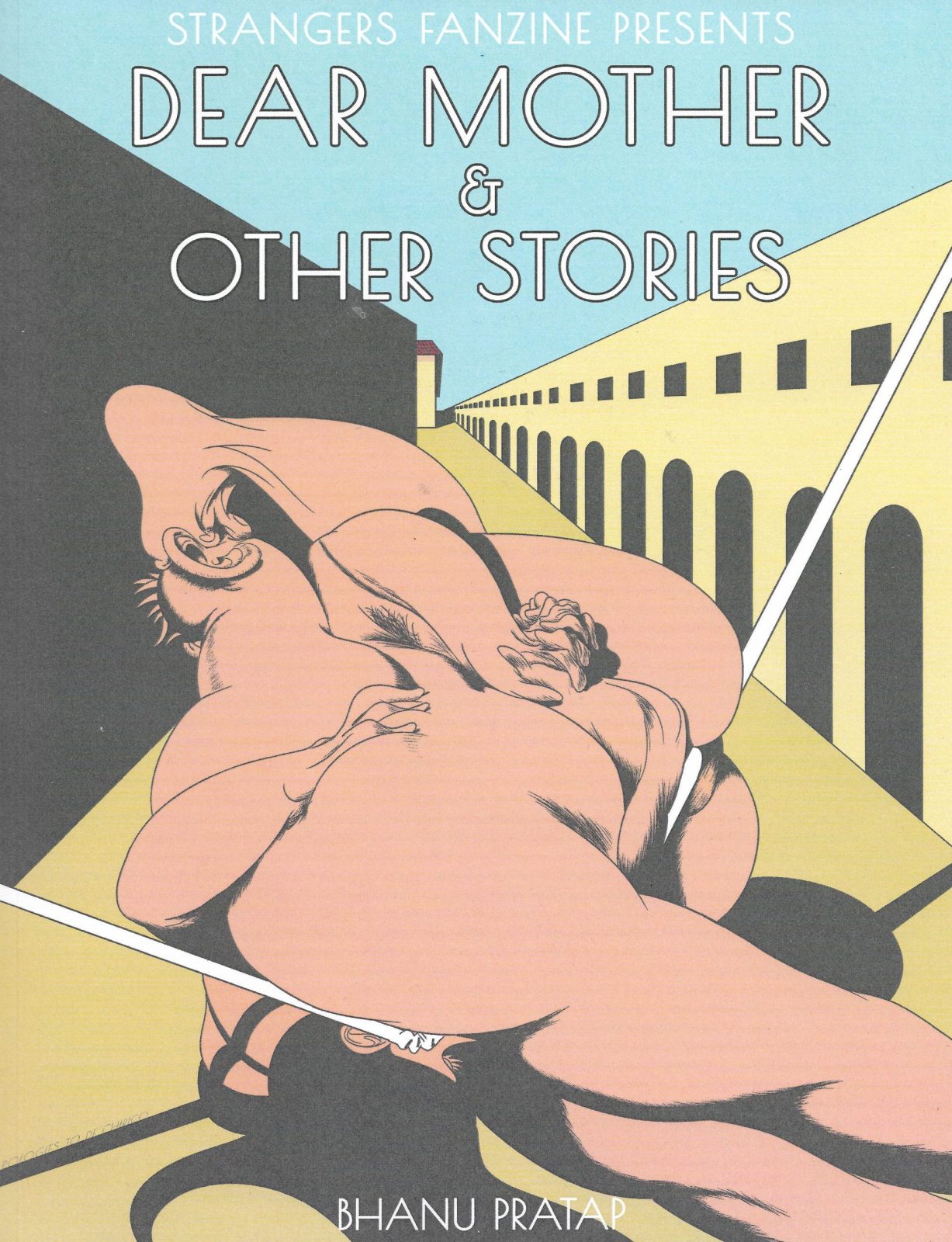

Dear Mother & Other Stories by Bhanu Pratap (Strangers Fanzine)

Pratap is my winner for Rookie of the Year with this collection. His anatomy (and talent) is otherworldly and every single panel has something—a hand gripping a pipe, a tear being squeezed out of an eyeball—that is breathtaking.

Jonna and the Unpossible Monsters by Chris Samnee, Laura Samnee and Matthew Wilson (Oni Press)

My oldest son is comics-obsessed (as much as that pains me to say), and reading this series together, monthly and in traditional format, has been a real treat this year. The storytelling isn’t trite like 99% of all kid’s comics, and Chris Samnee’s art is always unfailing. Jonna has to be one of the best all-ages comics since Bone.

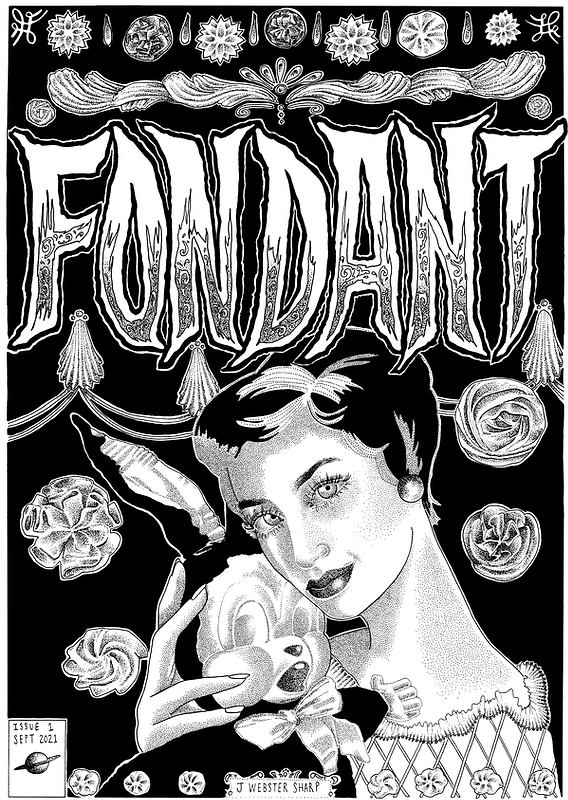

Fondant #1 by J. Webster Sharp (self-published)

I read three of Sharp’s self-published comics this year and each one made me feel nauseated - which is a good thing! Her stippling is impressive and her subject matter is usually sexual and abhorrent. Like with Pratap, Sharp feels like someone who will be an important figure in comics for many years to come.

“The Gift of Time” by Lauren Weinstein (Slate)

I’m a huge Weinstein fan (she also made my “Best of” list in 2018 and 2020) and this story cements her as one of comics’ best introspective thinkers and autobiographical cartoonists. Weinstein has a special ability to portray human emotion in a way that’s frank, humorous and warm.

In 2021 I read comics late at night, curled up in my messy bedroom, finding solace in drawings of cute girls and explosions or whatever else. I read comics with my phone open, snapping pictures of pages to harvest as content on my social media accounts for friends I may well never be near. I read comics at the laundromat, bored and mildly uncomfortable, wanting to be done but thankful for the hour or so where I could do a little non-required reading. I read comics on my computer, because review copies don’t often come to me by mail now and I had to adjust; I am thankful when they do not expire. I read comics with my girlfriend, huddled together cozily with a romance comic or a monster comic open between us, sharing the gentle thrill of an illiterate girl’s love for a businessman or the menace of Rommbu (shout out to Rommbu). I didn’t read enough. Who does? Anyway here’s some of what I liked, out of the comics that were “new”:

Mercyless: 2017-2021 by Inés Estrada (Gatosaurio)

A sketchbook zine and a chronicle of traumatic illness and injury, a break from reality and the humbling return. Estrada collects an artistic document of her own painful survival, a thematic continuation of her prior zine Cherry’s celebration of living in fucking reckless creativity until you might die, because you will die. A great autobiography.

Dear Mother & Other Stories by Bhanu Pratap (Strangers Fanzine)

XXX-rated slapstick comedy about bodies already mashed into paste contorting further in a poignant attempt to climax. Pratap works wonders in these comics that I cannot describe without reducing; at risk of hyperbole his art simply has to be seen to be believed. The most exciting book I read this year.

Dear Sara, 1997, Summer by ohuton, translated by zhuchka (Glacier Bay Books)

An intimate, nostalgic short story about yearning for the moment when desires first seemed possible and being unable to go back. The sci-fi conceit that ties the work together just makes the quiet illustrations and little turns leading up to it even more poignant. ohuton’s characters are adorable; their wobbly, geometric line at once evokes teenage sketchbooks and early computer graphics. Just nice.

F by Imai Arata, translated by Ryan Holmberg (Glacier Bay Books)

I am still working on a review of this one as I write this - for now I will just mention that this comic is so much goddamn fun, so many neat little jokes in this about fascism, identity, all that cool stuff. It even has some Super Mario references! Gamers will love it.

No. 5 Vols. 1 and 2 by Taiyō Matsumoto, translated by Michael Arias (VIZ)

Feels pretty bizarre to call this my favorite comic of 2021 seeing as it is a perennial favorite, and one of the quintessential post-9/11 comics, but it would be horrible not to mention a translation of this masterpiece finally appearing in print after all these years, hell yeah.

Love at First Fright by Bonnie Guerra (self-published)

Currently only exists as unedited scans on her Patreon but there’s no way I couldn’t mention this. It is truly joyous to read unabashed smut by an artist who really understands and appreciates “gridlock”, and Guerra’s lively, refined line makes that rare pleasure even more delightful. Guerra is an impeccable cartoonist who is exploring transgender fantasies and the wonder of our bodies unapologetically. I am looking respectfully.

* * *

Some comics that aren’t from this year but I only heard about this year, fuck you.

Burning Sound by Yuichi Yokoyama (888books)

This comic is so goddamn cool my man lit the sound effects on fire!!!!!!

The White People by Ibrahim R. Ineke (Sherpa)

The best horror comic I’ve read in ages amid an absolute flood of brilliant artists trying to make something I would call the best horror comic I’ve read in ages - when it went into full color I screamed. I haven't yet had a chance to read Eloise, which actually came out this year; I imagine it's sick as hell too.

* * *

Comics I reviewed that I loved a lot.

Children of Mu-Town by Masumura Jūshichi, translated by rkp (Glacier Bay Books)

Rabbit Game by Miyoshi, translated by Ryan Parker (Glacier Bay Books)

A.B.O. Comix: A Queer Prisoner’s Anthology Volume 4, Casper Cendre ed. (A.B.O. Comix)

Geniacs! by Liby Hays (Landfill Editions)

Even Though We’re Adults by Takako Shimura, translated by Jocelyne Allen (Seven Seas)

* * *

I probably forgot about loads of great comics, probably some by people I’m friends with. I'm sure I’ll get around to reading the actual and definitive best comic of the year tomorrow, oh well, c’est la vie. So I never actually finished reading Monsters, what are you gonna do, sue me?

Oliver East - You Can’t Draw the Same Tree Twice (self-published)

East has done comics based on walking before, drawing and walking and writing, making the most true autobiography comics ever - we walk WITH him. This new book is based on eight days of more walking and drawing, with words added later like a commentary track. The direct raw drawings with the considered, poetic and funny text feels new even for East’s always new work. New new! He mentions “panning for gold.” Well, you found it. (Also, his active and zany Patreon is well worth the price of admission.)

Simon Moreton - WHERE? (Little Toller Books) and other work

I interviewed Moreton last summer about WHERE? for TCJ and I still go back to the book in jealous amazement. A thick book of remembering a grief where Moreton uses everything he can think of—drawing, comics, photo, text—to conjure and remember. His other publications extend this search and are just as powerful. Wonderful.

Todd Webb - The Poet (Second House)

Webb whittles and peels back layers to find more and more in these spare but vast strips. A man, a bench, a pigeon; THE WORLD. They hang out up the street from Charlie Brown and in the wake of Thoreau, Bushmiller and Cage. Seen for free daily on Webb’s instagram feed, but they are even better collected in small digests that look and feel like old friends.

Melissa Mendes - Freddy Comics (self-published)

When these arrive at my house every month or so there is a battle for them among my family, which is the greatest compliment a comic can get. A kid’s landscape that is nutty, sad, happy, lonely and grinning. Mendes makes work that is deeply human and feels like being a kid, as my kids can attest to. Patreon here.

Andrew White - Yearly, etc. (self-published)

White’s generous, light-filled and pulsing work is COMICS, all comics, pushed around in various ways to the edge of what they can do. He puts a grid on the world and, like a sieve, pulls things out. Another gold-panner - and also like Oliver East, White teaches one how to read his work. His Yearly self-anthology was broken into a few issues instead of one and it felt right for his work, like seasons.

Having struggled to find ways to marry line and shape, I am happy and envious to see Gent do it so splendidly, in fantastic unexpected ways. The work shimmers and burrows. Her line twists and whips. There’s a lot for me to steal from (which is my highest compliment).

Daniel Warren Johnson, Mike Spicer & VC's Joe Sabino - Beta Ray Bill (Marvel)

I was a kid reading Thor when Beta Ray Bill was introduced, and though this work has a not-great story and missed opportunities for bigger and smaller moments, it is as visually powerful and fun to see as Simonson’s ancient work. I know, I’m supposed to be all classy and fancy, but this is great to see and look at and that’s ok to do too.

An Alien Who is Also a Mum by Philippa Rice (self-published)

A short and sweet 16-page musing on the soul, motherhood, the psyche and existence. The story is a confession: Philippa admits to being an alien parasite hosted in a human body, observing life here on earth. Perhaps it's a metaphor for how motherhood can take away or alter one's perception of self, with Philippa talking about feelings of detachment, of becoming a vessel for childrearing? Perhaps. I don't usually read so deep into minicomics, happy to just skim along the surface, and the surface of this one is great too. The book feels like it was painted at the kitchen table and it perfectly captures the chaos of life with small children and the existential feelings that creates. You should definitely read it if you get the chance. Perhaps I've made it sound more highbrow than necessary, it's just a joy to read.

I picked it up at the ShortBox Festival, which was a real comics lifeline in a year where I barely left the house. A digital month-long festival debuting all-new creator owned work. I only picked up a handful of titles but they were all quality. I hope Philippa goes on to put this comic in print, or make it available elsewhere. Watch this space, I'll be sure to shout about it all over the internet.

* * *

A lot of my other favorites this year I was lucky enough to discuss with the authors right here at TCJ. Zara Slattery's horrific and beautiful Coma, Gareth Brookes's medieval and worryingly relevant The Dancing Plague, Richard Short's melancholy and hilarious Haway Man, Klaus! and Hurk's retro-futuristic crime caper Jinx Freeze.

Over on Instagram I've really enjoyed Lauren Weinstein's The Gift Of Time, Daniel Locke's Isolation Station, Nick Edwards's Kingly, Tor Freeman's The Temptation of Mr Rose and all of Derek M. Ballard's brilliant autobio comics. Somebody please publish these, Derek's line and wit are such a pleasure and it's an eye-opener into an America I was naïve of... my whole vision of America being based entirely on sitcoms like Diff'rent Strokes and The Wonder Years.

I used to love best of lists, especially the ones for this magazine. Good effort in the arts thrown an endorsement by whichever person passionate about your chosen field you happen to believe in, a harmless thing to look forward to at year's end. But, increasingly, as art becomes more and more of an irreducibly (quite the opposite) vital thing to me, best of lists feel like a cheat. Not in the ‘well, how can I possibly narrow it down’ way, or even the ‘can the best even be defined, after all and et cetera?’ sense. Yes, while I am in favor of comics as a whole (including everything from a refined line that I find pleasurable to hacked out cross hatching that I find repellent) existing as a unit that strengthens itself as a multi-intentioned web rather than praise being directed towards one section, my aversion to best of lists isn’t as worked out as all that.

For a comic to really be part of one's life in any kind of consequential way, less than a year's time feels presumptuous. A beautiful comic that came out in September? Whose to say it’s the best (or anything really), as it's only filtered in and out of ones brain for a few months. If anything, it’s too much pressure for all involved, especially the comic. It’s hard to know what these pamphlets are capable of if you don’t let them breathe.

So, over the years for best of lists, I’ve decided to only talk about artists that have been around a long time and whose art has earned the benefit of the doubt, meaning like it or not, it’s of consequence - and more importantly, the work has breathed for decades already, the new entry existing within that breath. Often times, the only way for veteran artists of this industry to break into these lists is to do something ‘correctly’ or ‘ambitious’, which in the medium of comics means: lots of pages and/or blatantly topical subject matter. As the direct market dies and the bookstore market becomes the reality for artists and readers alike, this situation cements itself. There is one book this year (by a grand old gentleman of comics whom I mostly adore) which resembles a phone book. The story itself may be uneven—ham fisted if we’re being honest—but: phone book! Length! Comics aren’t just for kids anymore, because they’re heavy.

On the other hand: a comic like Mike Mignola’s Sir Edward Grey: Acheron (colored by Dave Stewart, lettered by Clem Robins) (Dark Horse) contains perfect pages and nothing else, but there’s only 22 of them, so you won’t hear much about it. A one-shot comic that contains 0% chaff? There’s just no context for that kind of thing anymore, besides what remains of direct market diehards, if they happen to notice it on the stands at all.

I read this comic in the last week of 2021. It’s essentially a dialogue between Edward Grey (Acheron) and the demon Eligos, with Grey slowly trying to convince Eligos of a new and evolving reality that both are involved in, but only one of them recognizes. As always, Mignola is sampling tones and angles from throughout the recorded history of storytelling, but the crucial personal tone he inscribes on top of everything has only gotten meatier and more authoritative in recent years. Characters retell events from earlier entries in Mignola’s sprawling world, as the texture of what Mignola has built for decades gets subverted, then preserved, then rearranged, then undercut, then given a new clearing. In Mignola’s hands, this is all organic, never ever arbitrary.

As comics fought its hard won journey into bookstores, this magazine’s corner of concerns most likely assumed it would join Nabokov or Austen on the shelves. However, bookstores were quick to explain that they sell a lot of celebrity cookbooks, and we all quietly made peace with this. After all, is interesting drawing that important to comics? Perhaps talking heads explaining Wikipedia articles will pass? What’s the page count? To be sure, Mignola will never be excluded from these shelves, even as the care he puts into every corner of every page becomes increasingly an oddity there. And yet, the pleasure of reading his drawings in the correct way, as a package containing exactly what it needs to contain—22 perfect pages of frankly experimental drawings—is a particular experience that comics in their most mainstream manifestation seem to be moving far away from. For those of us who still care to find a comic shop, we can enjoy reading a couple dozen pages of true art sold to us for the low price of $3.99.

Gutter Hunter #1 by Robin Bougie (self-published)

Robin Bougie is the writer-cartoonist-publisher-hyphenate behind 34 issues of Cinema Sewer (1997-2021), a remarkable magazine covering all forms of disreputable cinema, including pornography. Due to my own residual Catholic prudery, I only occasionally read Sewer, but every time I was impressed by Bougie’s cartooning, his dedication to investigating and interviewing obscure filmmakers and performers, and his willingness to hand-letter almost all the text in each issue. Bougie explains his preference for hand-lettering as part of his “hand-made aesthetic that makes you feel not like you’re reading something from a corporation or a committee, but like a letter from a friend.”

Those words are from the first issue of Gutter Hunter, Bougie’s newest project, hyped on its cover as “The Adults Only guide to history’s wildest independent comics!” Hunter’s articles, written and illustrated by Bougie, are a mix of opinion pieces (rants against comic shop price gouging and corporate exploitation of creators), interviews (with artists Larry Fuller, Julian Lawrence, Marc Bell, others), and reviews of older alt-comix, many from the black-and-white boom of the mid-1980s through the early 1990s. All are entertaining, colloquial and smart, and they make Hunter an excellent addition to the recent wave of comix review zines like Brian Baynes’ Bubbles and Eddie Raymond’s Strangers.

But I also found reading Hunter to be a melancholy experience. Bougie’s dogged research and empathetic reporting on the artists of such forgotten works as Ultrafiction (1987) and Varcel’s Vixens (1990) reveals some broken lives and sad endings. One abandons a career as a rock musician to become the cartoonist for tracts produced by a pedophilic Christian cult called the Children of God; one becomes a Trump disciple; and one named Susan Van Camp dies in obscurity at the age of 61 of breast cancer, as chronicled by her husband’s blog entries, found by Bougie on waybackmachine.com. (Bougie on Van Camp’s passing: “I guess it’s just a scary idea to me, that if you disappear suddenly everyone will stop thinking about you, out of sight, out of mind—and it’s almost like you never existed.”) Most of the profiles in Gutter Hunter remind us how difficult it can be to make art in a world of ruthless commerce and increasing isolation. Bougie would know.

Wild #2 by Cristian Castelo (Floss Editions with screen-printed covers by Sun Night Editions)

On the back cover, large black numbers give the publication date as “2020,” though Castelo didn’t start advertising Wild #2 on his Instagram until early 2021. Maybe it’s not actually a book from this year, but I read Wild in mid-2021, so I’ll write about it anyway.

If Bougie’s Gutter Hunter is in some measure about the sacrifices and losses of the long-distance cartoonist, then Wild #2 is the opposite: an example of a gifted young artist pitching lightning bolts into every panel. The artist under consideration is Cristian Castelo of Daly City, California, a member of the Freak Comics Collective with Miles MacDiarmid and Mara Ramirez, and a dedicated self-publisher who began Wild—named after his protagonist, Wild Rodriguez—as an inkjet zine several years ago before upgrading Wild’s saga into a large-format, perfect-bound treasury. I think Wild #2 reprints issues #4-6 of the zine, but I’m not sure; I’m extrapolating from Internet information. (Corrections are welcome in the comments.)

Helpfully, Castelo summarizes Wild #1 on his first page. The year is 1975. Wild attends an Arizona high school with a savage roller derby league, and she joins a team with a dismal 0-10 record, the Rocket Rollers. They lose their first match, but Wild’s impressive skills earn the attention of two of the school’s top roller derby queens, Darla DeVal and Dixie Belle. Wild #2 begins the day after this first match (“Sunday!”), alternating between Wild and her teammates butting heads with their next opponents at a Mexican restaurant, and Dixie and Darla scrapping at a house party. The second half of Wild #2 likewise cuts between the Rocket Rollers’ battle against Las Locas and an exhibition match in Las Vegas between Dixie’s 8-Ball Bruisers and “semi-pro league champions” MMMM and the Pound Puppy.

Castelo’s narrative charts his influences: teen movies like Dazed and Confused (1993); Jaime Hernandez (“Las Locas” has to be a deliberate homage), maybe even on Castelo’s loosey-goosy magic realist approach to characterization. (Las Locas’ leader is Samantha Rivera, a face-scarred sociopath in an eyepatch and a matador costume, and the Pound Puppy is a creepy masochist in a Goofy costume.) Castelo even touches on serious issues: while ordering at the restaurant, Wild is publicly humiliated when she reveals that she can’t speak or understand Spanish.

Wild #2’s story is a blast, but for me the primary attraction is Castelo’s art, which habitually maximizes retinal impact. Smash close-ups appear on every page; figures sweat, cry, grimace, and scream in juicy, hyper-cartoony exaggeration; the climatic roller derbies in Castelo’s story explode into spaces that abandon gravity, naturalism, and lifelike perspective. On a page about 1/4 into the comic, Toro, Samantha Rivera’s horned, masked second-in-command, pushes Wild’s face against school lockers. Bursts of orange emanate from Wild’s head, transmitting pain, while Samantha, in her yellow matador suit and an orange bolo tie, stands to the left of Toro and Wild. (Castelo’s illustrations are printed in luminous Riso inks like Lake, Red and Yellow.) Much in this panel isn’t technically “correct”—Toro’s arm bends in three impossible ways while shoving Wild—but I don’t care. I’m watching a born cartoonist play with their medium.

Special thanks to Stephen Floyd for recommending Castelo’s work.

Goes by Luke Kruger-Howard (Goes Books)

You’ve probably read this, because artist Luke Kruger-Howard—the creator of such comics as Our Mother (2016) and Talk Dirty to Me (2016)—distributed physical copies of Goes at no cost through the mail, until he ran out (though a free digital download remains available). Kruger-Howard believes that price point shouldn’t block anyone from enjoying culture and comics, and to keep his project solvent, he invited donations from those who could afford to buy books, for themselves and others. Call it a form of literary/artistic mutual aid; I call it idealistic and touching.

Goes is a short story collection. The first and longest piece is “Men’s Holding Group”, a vision of both the near and far future where repressed, scornful masculinity is gradually replaced by men willing to build healthier, more intimate friendships. “Holding Group” unfolds mostly on the micro level, from the p.o.v. of a young father in a trucker’s cap who wants to learn how to be close to his infant son. The other stories—“Dead Dog,” “Let Me Show You Around,” and “Goes”—are autobiographical, addressing such topics as the death of a beloved pet, struggles with mental illness, and, in a return to a central theme of “Holding Group”, Kruger-Howard’s own relationship with his toddler.

Speaking of autobiography, I’ll shamelessly tell a personal story to reveal what Goes meant, and means, to me. The consensus is that 2021 was another disappointing, COVID-spoiled year, but as ever, the pain wasn’t spread equitably: I especially worried about Joe, a close friend whose last parent, his mother, died in the early fall. I phoned Joe and we talked candidly for an hour about his mother’s brutal slide into dementia. At the end of our conversation, inspired by “Men’s Holding Group” and the tenderness of Kruger-Howard’s art, I realized that in all the decades we’d known each other, I’d never told Joe that I loved him. So I said it. After a brief pause, Joe said the same to me, and we made tentative plans to see each other for the first time in five years in 2022.

I teach a comics class every semester, and whenever possible, I invite cartoonists to Zoom with us to discuss their art. In the fall, Kruger-Howard was our guest. Before our talk, my students read Goes and expressed in written assignments how deeply they were moved by it - one summed up Kruger-Howard’s little book as a vision of “a world where men are comfortable enough in who they are to show love, affection, and emotion to each other. This is how the world should be.” And during the class interview, after my students asked a few insightful questions, I found myself telling Kruger-Howard that it was difficult for me to tell Joe that I love him, and how his little utopian book gave me courage. That’s why Goes was my favorite comic of 2021.

* * *

And here’s more 2021 comics-related publications that I loved:

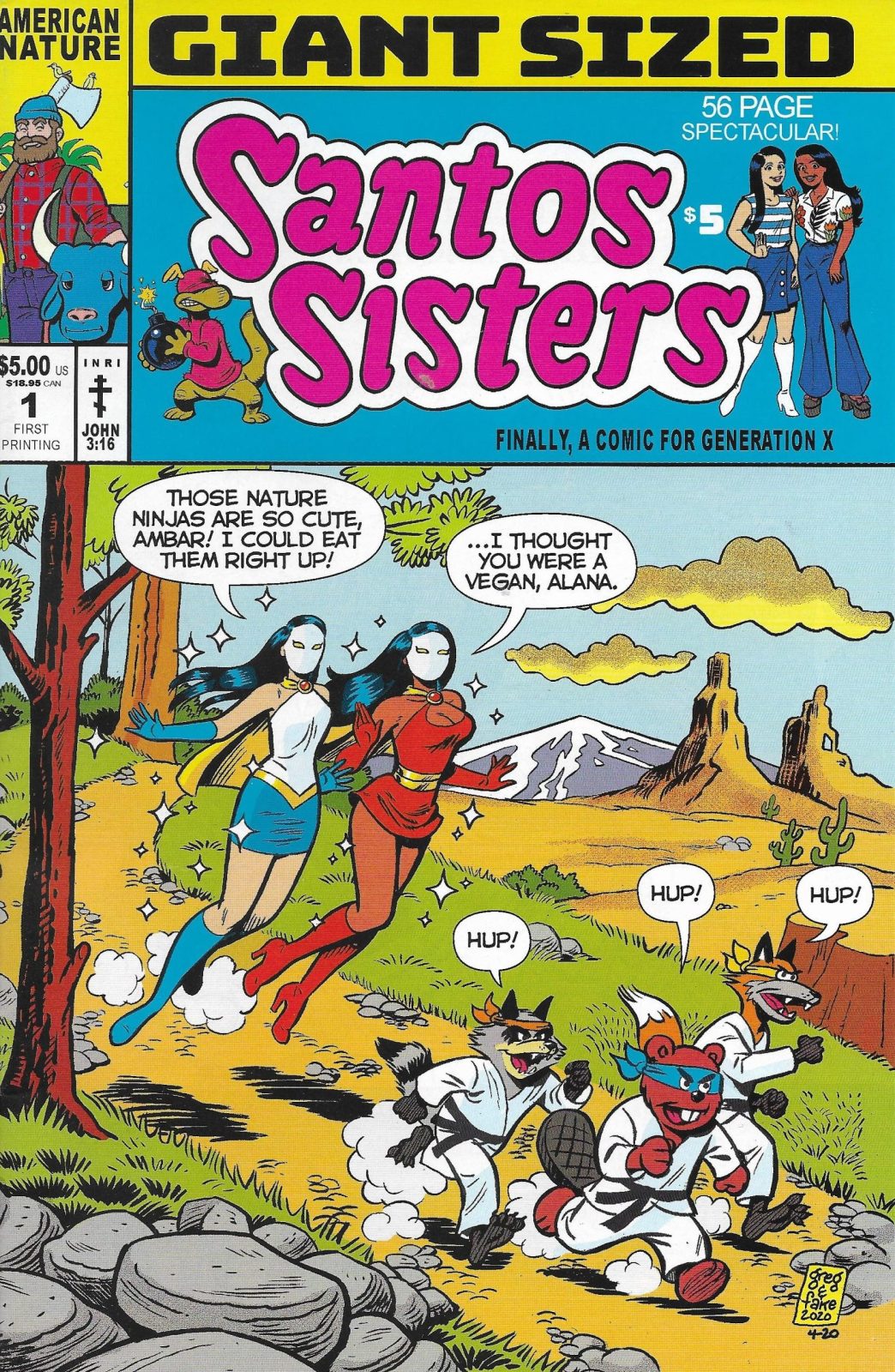

All of the Marvels: A Journey to the Ends of the Biggest Story Ever Told, Douglas Wolk (Penguin Random House); Bat Kid, Inoue Kazuo, translated by Ryan Holmberg (Bubbles Zine Publications); Bubbles: an independent fanzine about comics and manga #9-10, Brian Baynes ed. (Bubbles Zine Publications); Children of Mu-Town, Masumura Jūshichi, translated by rkp (Glacier Bay); Cinema Purgatorio, Alan Moore and Kevin O’Neill (Avatar); (Cover Not Final), Max Huffman (AdHouse Books); Faster, Jesse Lonergan (Bulgilhan Press); Four-Fisted Tales: Animals in Combat, Ben Towle (Dead Reckoning); The Gift of Time, Lauren Weinstein (Town Clock CDC); Ginseng Roots #8, Craig Thompson (Uncivilized); Grass of Parnassus, Kathryn and Stuart Immomen (AdHouse Books); It’s Life as I See It: Black Cartoonists in Chicago, 1940-1980, Dan Nadel ed. (New York Review Comics); Look Back, Tatsuki Fujimoto, translated by Amanda Haley (VIZ); Mysterious Travelers: Steve Ditko and the Search for a New Liberal Identity, Zack Kruse (University Press of Mississippi); November, Volume 4: The Mess We’re In, Matt Fraction, Elsa Charretier, Matt Hollingsworth & Kurt Ankeny (Image); Old Gods and New: The Jack Kirby Collector #80, John Morrow and Jon B. Cooke eds. (TwoMorrows); Rust Belt Review #1-3, Sean Knickerbocker ed. (self-published); Santos Sisters, Fake and Greg Petre (American Nature); Slow Death Zero, Jon B. Cooke ed. (TwoMorrows); Son of Tomahawk #141, Matt Seneca (self-published); Spain: Volume 3: My Life and Times, Spain Rodriguez and Patrick Rosenkranz (Fantagraphics); The Strange Death of Alex Raymond, Dave Sim and Carson Grubaugh (Living the Line); The Thud, Mikaël Ross, translated by Nika Knight (Fantagraphics); Trots and Bonnie, Shary Flenniken (New York Review Comics); Wicked Things, John Allison, Max Sarin, Whitney Cogar & Jim Campbell (BOOM!).

2021, even more than 2020, has been harrowing for my family: a year of shocks and losses, followed by the fog of bereavement. My reading has suffered. My bedside stack of unread comics is perilously tall, though I’ve been bingeing digitally—Marvel Unlimited, Hoopla, DCU Infinite—in long, nighttime fits.

So: Giant Days, Immortal Hulk, Ms. Marvel, Ultimate Spider-Man, Claremont-era X-Men. Plus, catching up with books from previous years: Snapdragon, Godshaper, Kiss Number 8. Time out of joint! That, and no small press festival for me this year, means I’ve missed even more great comics, print and digital, than usual.

That said, I’ve enjoyed renewing my weekly LCS habit. I’m embarrassed to admit it, but I’ve been a crisis collector, following floppies because the habit makes me feel good, or at least less broken. Series like Adventureman, Echolands, Fire Power, Head Lopper, and ORCS! have kept me in the swim.

I enjoy being a fan who gets a regular fix. Despite that, manga and webcomics sadly remain sidelines for me, slightly apart from my daily or weekly rituals (I do mean to change that). In any case, here is a bunch of print comics from 2021 that I’ve found absorbing:

Asadora! Vols. 1-4 by Naoki Urasawa / N Wood Studio, translated by John Werry (VIZ). Kaiju and barnstorming aviation collide with the 1964 Tokyo Olympics! The redoubtable Urasawa brings his stylized naturalism to this frankly nationalistic weird tale featuring postwar angst, creepy spies, a monster, and a gutsy flying heroine. Addictive.

The Gift of Time by Lauren Weinstein (Town Clock CDC). Published by and benefiting Town Clock, a domestic abuse shelter, and adapting Weinstein’s experiences teaching art there, this comic interweaves survivors’ stories in loving testimony to community and creative resistance. I first read this on Slate.com, but love the print edition.

Ginseng Roots by Craig Thompson (Uncivilized Books). Thompson’s best? This serial about ginseng farming in the Midwest started shakily as autobio (revisiting the upbringing fictionalized in Blankets) but has embraced reportage, history, and biography. Readers leery of Thompson’s appropriations may balk, but wow is this something: didactic, technical, inventive, and rapturous.

Goes #1 by Luke Kruger-Howard (Goes Books). My friend Craig Fischer describes this better than me. A not-for-profit, anti-capitalist comic (utopian in the best sense), Goes focuses on physical affection and tenderness among men. Gently self-mocking and yet quite serious, it is beautifully drawn, inventive, and piercing - a hand-sized gem.

The Good Asian by Pornsak Pichetshote, Alexandre Tefenkgi and Lee Loughridge (Image). A 1930s Chinatown noir set against America’s long backdrop of anti-Asian racism, this series—at once historical and timely—teaches as it stings. Its furious didacticism invests the genre’s usual damaged, conflicted characters with new meaning. Gripping, nasty, powerful.

Harriet Tubman: Toward Freedom by Whit Taylor and Kazimir Lee (Little, Brown and Company). Another excellent entry in the CCS series of graphic biographies for young readers, Toward Freedom is at once hopeful, suspenseful, tough-minded, and open-ended. Knowing characterization, unhurried pacing, and deft cartooning make this subtly instructive book endlessly re-readable. Share it!

Let’s Not Talk Anymore by Weng Pixin (Drawn & Quarterly). This multigenerational family story depicts mothers and daughters at five points in history, “making the space to wonder about the women who made us.” Loss and trauma echo back and forth, poignantly, in exquisite painterly style, until a beautiful, affirming conclusion.

Mamo by Sas Milledge (BOOM!). These days, comics about witches are legion. This one is special: an understated, queer-affirming YA fantasy about female friendship in a haunted town. It recalls Miyazaki (no bad thing). A thoughtful approach to magic, a believable love story, and gorgeous art - this fairly bowled me over.

No One Else by R. Kikuo Johnson (Fantagraphics). This elliptic (blink and you’ll miss it) story of a grieving Maui family whispers its messages but trumpets its influences, recalling Xaime, Tomine, and Jordan Crane. Not a problem! Oblique, spare, elegant, and needle-sharp; muted but restive. This heartbreaker begs to be reread.

Raptor: A Sokól Graphic Novel by Dave McKean (Dark Horse). A fascinating case of artistic overreach? In this esoteric meta-story about a grieving writer’s encounter with a fictive(?) character, McKean strives mightily after verbal as well as visual poetry. The results: abstruse, maddening, but gorgeously layered and worth wrestling with.

The Secret to Superhuman Strength by Alison Bechdel, with Holly Rae Taylor (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt). No surprise, as this is probably the mainstream graphic book of the year. Though its ending seems forced (I bet Bechdel could have gone on forever), its generosity, playfulness, and myriad sly observations make it a treasure.

Thirsty Mermaids by Kat Leyh (Simon & Schuster). A ribald fairy tale about three boozy, hard-partying mermaids who get stuck on dry land and must somehow get back to the sea. Wild, elastic cartooning, winning characters, some unexpected deepening in the home stretch, and a boffo climax - what’s not to like?

The Thud by Mikaël Ross, translated by Nika Knight (Fantagraphics). This dramedy about life in a planned community for people with disabilities (Neuerkerode, Germany, a real place) strikes a nervy balance between sentimental and unsentimental humor. Raw, salty moments, a refusal to idealize or patronize its subjects, and lovely, color-rich pages.

Tono Monogatari by Shigeru Mizuki, translated by Zack Davisson (Drawn & Quarterly). A curiosity: Mizuki’s manga adaptation of stories from Kunio Yanagita’s 1910 classic Tono Monogatari [Tales of Tono], a compendium of supernatural tales and pillar of Japanese folklorism. Mizuki recreates these legends—offhand, humorous, uncanny—in wryly self-deprecating but scholarly form.

Trots and Bonnie by Shary Flenniken, edited and designed by Norman Hathaway (New York Review Comics). An artfully curated edition of Flenniken’s brilliant but under-read strip, which started in underground comix, then ran for years in the National Lampoon. Of its time, ahead of its time, deliciously cartooned, and damn funny - an overdue retrospective.

Tunnels by Rutu Modan, translated by Ishai Mishory (Drawn & Quarterly). In this sharply-written, Tintin-esque political caper, Israeli and Palestinian treasure hunters uneasily collaborate on a clandestine archaeological dig to find the Ark of the Covenant. The cast is amoral, driven by careerism, bad blood, and zealotry - yet likable, funny, and complex, like the book.

What Is Britain? by Simon Moreton (self-published)

Anything, please, that recognizes art probably won't change the world. Anything that accepts mass struggle is the lever to create policy shifts, rather than hoping fragmentation into individual identities quarreling with each other will do the trick. Anything that shows erasure of existing structures is possible. Such as, say, the statue of British slave-trader-slash-merchant Edward Colston being pulled off its plinth in June 2020 and dumped in Bristol Harbour from a spot outside a chintzy all-you-can-eat buffet joint that your TCJ correspondent can see from his house. Simon Moreton's zine What Is Britain? ends with an image of that statue in mid-fall, a modification of a local photographer's image which caught its downward arc towards a serendipitously placed placard reading Fuck Trump Fuck Boris - words that happen to be upside down, for extra Discordian disruption. Moreton's imperfect polemic (the artist's phrase) collages new and old photos, found texts, portraits of the recent and unquiet dead, and Moreton's own broad-stroke cartooning for a kick in the nuts of the Tory nation, although these are hardly moving targets. A 2017 photo of Michael Gove meeting President Trump at the behest of Rupert Murdoch, an un-special relationship from every angle, is processed so Gove has the rictus grin of the Joker. Boris Johnson rendered in Moreton's thick ink strokes is pasted onto a pile of skulls as if caressing them, the cartoonist's intuition putting him ahead of Johnson's reported quote about being prepared to "let the bodies pile high" rather than impose lockdown which emerged only after the zine came out. Something wearing a rosette of the UK Independence Party is manipulated into an acid-etched dissolving figure from Francis Bacon's nightmares, the zeitgeist made poltergeist. Whether risograph samizdats cutting across accepted thought can still help us now is anyone's guess, but we should be giving it a shot.

Zig Zag by Will Sweeney (Fantagraphics)

The revolution will be colorized. Zig Zag's 24 wordless blazingly colorful pages are a fractal sequence of actions, any one of which can't happen before its predecessor, a preset sequence of contingency plans that could have been laid last month or last century. Characters are called forth by other characters and then consult different characters and merge into yet further larger ones, eventually coalescing into a multi-pilot humanoid robot that tackles an armored dictator visually coded as El Presidente. Exactly what's what matters less than the sight of revolution through collective action, plus the cyclic certainty that at some point another leader will need removal and another team of small cogs in a larger project will emerge, proletarian enough that they get to the scene of the action on public transport.

LAAB Magazine #2, Ronald Wimberley & Josh O'Neill eds. (Beehive Books)

Ronald Wimberly published issue #2 of his broadsheet arts newspaper a year after issue #4 when there is as yet no issue #3, and mailed it out in an envelope marked Eat Shit in big letters, all of which are the kind of foibles that you want from committed artists. Folding comics into and around text articles fuses the two transmissions together, a pair of progressive artforms serving their best radical purposes in a manner ready for pasting onto a bus stop, or the empty plinth where a statue used to be.

The Twelve Sisters of the Never-Ending Castle by Shintarō Kago, translated by Iain Halliday (Hollow Press)

Shintarō Kago's art is entirely political: soft bodies unfolding and unzipping and unpeeling and twisting in calm ecstasy will always have an anti-fascist vibe, on top of whatever topic of radical modification is powering the stories themselves. Twelve Sisters is the second Never-Ending Castle book from Hollow Press, and appears with a functioning English translation, which counts as progress after the first one; but its morphing bodies are less about calm ecstasy than very active states of change. The first book had Kago's infinite civilization of towering pagoda cloud-scrapers collapsing under the pressure of inequality and economics, when the pressure built up to the point that the comic's layouts and panel order broke down alongside. This time the story has twelve women resisting the indignities and brutalities of their domestic situation by rupturing their bodies and taking a society with them. Characters reach into their own unspooling viscera and bring down the world, as all should in one way or another.

Monsters by Barry Windsor-Smith (Fantagraphics)

Barry Windsor-Smith emerges from a period of silence with a book so intensely focused on the despair of the inescapable past and the utter wickedness of mankind that you wonder what exactly the time offstage has involved for him. Is it now reactionary to see the actual Nazis as a cosmically potent source of death and despair for innocents miles down the timeline? Windsor-Smith is 72 years old, which surely plays a part in this choice of demons. But the story's weight pulls back into view the idea that the Third Reich is a low point for Western thought on such a scale that it surpasses a lot of raw history and acts as something closer to mystic catastrophe, a cultural devolution, the Un-Enlightenment. One day this idea will drift permanently out of artistic range altogether, a net loss if you ask me.

The Grande Odalisque by Jérôme Mulot, Florent Ruppert, Bastien Vivès & Isabelle Merlet, translated by Montana Kane (Fantagraphics)

Some reviews detected reactionary objectification of The Grande Odalisque's three libertine female criminals, although your beholder's eye could equally spot that objectification needs emphasis, focus, camera angles, exaggeration - and those aren't what Jérôme Mulot's and Florent Ruppert's art (with admittedly a contribution from big-bongos aficionado Bastien Vivès) deals in at all. The artists certainly depict their leading ladies in ways that don't require anyone to dip below physical perfection, but that's not the same thing. You might also note that the three sexy ladies are supremely competent and outwit oafish men by the score while ascending through the masculine ranks of outlaw life. The net effect—notwithstanding a few cops burned alive and the pauses while you recall various Luc Besson films—is charming, more laid back than the desiccated blue-balls horn of The Perineum Technique. Near the end a traumatized character on the back of a motorbike looks around at some passing buildings, where the fuzzy static of the lines and pastel coloring creates just the melancholy the comic is after: a slightly enchanted world of slightly enchanted people charging through it and living their best lives.

Mysterious Travelers: Steve Ditko and the Search for a New Liberal Identity by Zack Kruse (University Press of Mississippi)

A great moment from 1975 in Zack Kruse's new book on Steve Ditko has the comic artist completely inverting the intention of the script that he is illustrating and more or less bodychecking writer Gerry Conway into a hedge. Mysterious Travelers takes a nuanced and sympathetic reading of this kind of thing, while taking the opportunity to clunk a few familiar rent-a-trope interpretations of Ditko and his politics sideways too. Treating Ditko's individualism as a hands-on experimental tactic seems a better bet than assuming it was just the result of wrongthink, not least since it aligns this book with some others on the current cultural bookshelf relating our ills to the 1970s, that period of social fracture and environmental collapse and surveillance paranoia and the breakdown of consensus that obviously couldn't happen again.

Son of Tomahawk #141 by Matt Seneca (self-published)

More 1970s considerations. Although I'm ever more dubious about extended Close Reading as the approved method of writing about comics or anything else, and suspect we should wean ourselves off the habits of scholarship as a matter of some urgency, Matt Seneca's instincts for DC's old Son of Tomahawk series as having something to say about America's original sins of violence and racism is a valuable balloon to float, especially given the ambiguously optimistic worldview the comic eventually builds. Seneca's zine then adds a comic of his own, a flight of creative fancy that drives the thesis forward down the timeline. My heart sinks when film critics make film essays and turn art into charts and graphs; but comics critics making comics is a different kettle of creativity, since the act is likely to involve interpretation rather than just description, and throws a certain amount of the effort back onto the reader, which is pretty much the point of the visual arts. The last DC issue has Hawk's mother saying that one day Hawk might understand women, and this zine takes that as a cue to peer around the curtain and put Hawk into the contemporary racial mixing pot which America has always proposed and failed to make work successfully. Which means Seneca's strip is as much a piece of criticism as the written essay preceding it.

In no particular order:

The Secret to Superhuman Strength by Alison Bechdel, with Holly Rae Taylor (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt). Another strikingly presented, deeply personal opus from a bona-fide genius of the graphic memoir.

I Never Promised You a Rose Garden by Mannie Murphy (Fantagraphics). This personal chronicle of the history of racism and white supremacy in Portland, OR is mournful and chilling. Murphy's drawings, painted on crinkling notebook paper, are hauntingly perfect.

A Revolution in Three Acts: The Radical Vaudeville of Bert Williams, Eva Tanguay, and Julian Eltinge by David Hajdu & John Carey (Columbia University Press). A wonderful example of the ability of comics to present and bring to life little-known histories - the fact that the creators made it all feel relevant to modern times makes it downright valuable.

Montana Diary by Whit Taylor (Silver Sprocket). A sharp, funny travelogue that seamlessly mixes autobiography with U.S. history.

My Begging Chart by Keiler Roberts (Drawn & Quarterly). Put all of Roberts's books together and they tell a funny, poignant, richly-textured and ever-evolving autobiographical chronicle.

The Pleasure of the Text by Sami Alwani (Conundrum Press). Brainy, hilarous and scabrous. I finished this omnibus eager to see what Alwani will do next.

Ruining Your Cat's Life by Lauren Barnett (Kilgore Books & Comics). Barnett, a true original, makes weird fun out of this era of pandemic and lockdown with these wonderfully droll comics. I laughed out loud more than once.

Let’s Not Talk Anymore by Weng Pixin (Drawn & Quarterly). Delineated in gorgeous, naïve-style painted panels, this story of five generations of women deftly balances whimsy and heartbreak.

Fictional Father by Joe Ollmann (Drawn & Quarterly). Highly entertaining character-based dramedy with plenty of narrative surprises.

Save It for Later: Promises, Parenthood, and the Urgency of Protest by Nate Powell (Abrams ComicArts). Deeply felt, beautifully drawn comics essays about the challenges, traumas and inspirations of living during the Trump era.

Honorable mentions:

Too Tough to Die: An Aging Punx Anthology, Haleigh Buck & J.T. Yost eds. (Birdcage Bottom Books)

Factory Summers by Guy Delisle, translated by Helge Dascher & Rob Aspinall (Drawn & Quarterly)

2021 was a strangely cloistered year for me. While I did meet a small handful of new people, most of my contact with the world was via screens and phones. Part of that was a redoubling of creative efforts and part of that was still finding myself cautious in the face of an illness that I don’t want to pass on to any of my very vulnerable friends and relatives.

I spent a lot time delving into the catalogs of some artists and writers whose work I seemed to have missed for the last few years. So while it may have been new to me this year, it wasn’t new to the world. I have also found comics impossible to read on Kindle and haven’t found a new favorite comic store to replace the one that was killed by COVID. Because of this, most of my favorite things have come to me via Kickstarter or other self-publishing venues.

When I Was Me: Moments of Gender Euphoria, Eve Greenwood and Alex Assan eds. (Quindrie Press). This book features single-page comics in a range of styles done by dozens of different artists and writers. It highlights moments, both intensely personal and somewhat universal, in the lives of trans people. One of the best elements is that while it does not sugarcoat the difficulties, it highlights the triumphs, large and small. It is a wonderful gift for trans teens or the friends and family of trans folk who would like to gain some insight or find a jumping off point to talk about the subject.

Partly Robot Industries Presents: Ability - Emerging from the Social Constraints on Neurodivergence and Disability and a is for aspergers: a personal glossary of spectrum life by Andrew Coltrin (self-published). These are zines like from the ‘90s. Copied, cut, stapled, and imperfect but genuine and sincere. The personal glossary is just that, an alphabetic listing of words and phrases that Coltrin likes, hates, has researched and come to terms with. They look at autism from within the spectrum and from the outside. His sense of humor, sometimes a little self-effacing, sometimes sardonic, always shines through. Ability is a follow-up. It is more “professional” in presentation, and features some comic pages as well as very informative text on other forms of neurodivergence, and how they often intersect with autism.

1956 Book Two: Movie Star by Steve Lafler (Cat Head Comics). The second installment of Lafler's 1956 series, this one has big moments, snarky revenge, sweet romance, and cool jazz, and leaves me wanting more.

The Night Mother by Melanie Gillman (self-published). When I saw that Melanie Gillman, author/artist behind As the Crow Flies and Stage Dreams, was offering a Halloween-themed 24-hour comic I jumped at the chance to order it. The story is sweet, mysterious and unlike anything I’ve read in a long time. It takes place in an unnamed historic time and place where a patriarchal church controls congregants’ lives. The central character suffers a second miscarriage and is divorced by her husband and shunned by the church. She still longs for a child. A strange woman presents her with a new chance at mothering, but those in power cannot leave her to her happiness.

Plus two items that won’t ship until next year, but I was very excited about being able to back this year:

Phenomenomix by Hunt Emerson (Knockabout), collecting bunches of his work from Fortean Times.

Cautionary Fables and Fairy Tales: North America, Kate Ashwin, Kel McDonald & Alina Pete eds. (Iron Circus Comics). An anthology of myth and folklore that won’t ship until April, but looks fantastic.

The exception to the Kickstarter/self-publishing line up is Bryan Talbot’s Grandville Integral (Dark Horse). If you read my interview with Talbot you will not be surprised that it was a favorite. Weighing in at over 600 pages, it collects all five graphic novels in the Grandville series and includes annotations about comics-based jokes and tips of the hat, historic and cultural references, and gives a hint at the huge amount of research went into the books to begin with. If you haven’t read this alternate history, anthropomorphic, action-filled, insightful romp of a series you are in for a huge treat. If you have read the single volumes it is a beautiful tome to grace your bookshelf, and having the complete story in one place can’t be beat.

Two other things that are not comics or zines or graphic novels, but that stood out in 2021 were vaccines and Cosmic Crisp apples.

Vaccines – not just the COVID-19 vaccine that has allowed me to go to a museum for the first time in two years, but more importantly the vaccine that kept two of my cats from dying of the horrible viral feline leukemia that cut my other cat’s life short at less than two years – with the last six months pretty miserable for him.

Cosmic Crisp apples – While they have probably been around for millennia I have only discovered them in the last few months. They have the crunch and crispness of a Fuji with more sweetness than the inedibly mushy Red Delicious.

Hoping your 2022 is full of tasty things.

I didn't read a whole lot of comics this year, but I do want to plug Joe Frank: Ascent (Fantagraphics), adapted by Jason Novak. I wrote a review of the book for TCJ earlier in the year, though it's less of a review, and more of an extended word dump about Chris Morris and other practitioners of the darker/quieter kind of comedy. After writing the thing, I went on a yearlong Joe Frank binge and renewed my appreciation. This book will not be on any other best-of lists, I imagine, but it's a loving tribute to a great storyteller who, despite his far-reaching influence, remains underappreciated.

There were also a lot of excellent comics from Germany. I very much enjoyed Nadine Redlich's Stones (Rotopol) (more on that later) and Anna Haifisch's Mouse in Residence (Spector Books) (more on that later, too). Max Baitinger has a beautiful-looking book out (Sibylla) (Reprodukt), which I haven't seen translated. I'm sure there's a lot of good books that I missed, but 90% of my reading this year has been in Russian - I used to avoid it at all costs, but nowadays it feels like having a private language, since I'm so far removed from actual Russia and all the fascinating things that happen there. Vladmir Sharov's Rehearsals ("Репетиции") made a particularly strong impression on me - a gentle, almost tender history of cruelty and resilience, at times hilarious and absurd, at times unbearably heavy.

Anne Simon had a new book out (Man in Furs, written by Catherine Sauvat, translated by Mercedes Claire Gilliom) (Fantagraphics) but I haven't read it yet - I'm sure it's brilliant. Everything she does is brilliant, and next year the third volume of the trilogy that started with The Song of Aglaia is coming out, and you should read it too. Lizzy Stewart had a book that I also haven't read (yet!) ( It's Not What You Thought It Would Be ) (Fantagraphics) and she's another artist that can be trusted to be brilliant.

Max Huffman's (Cover Not Final) (AdHouse Books) was a pleasant surprise - it's so rare these days to see an artist having fun with drawings and words. Sami Alwani is another young cartoonist with a great debut collection - The Pleasure of the Text (Conundrum Press). I'm excited to see what both of them come up with in the coming years.