The algorithms of my social media feed can sometimes seem like a constant loop of homogenized mediocrity, it can get me down. Thank goodness for Gareth Brookes. Over the last few years I've seen Gareth make comics using lino cut, monoprint, embroidery and wax crayon etching. From comics about old ladies who see visions in the supermarket, silent psychedelic science fiction, suburban teen angst to erotic eavesdropped conversations on the bus. Something for everyone, really. There's wry wit, deadpan delivery, they are fun and horrific, silly and strange, but always interesting, always something new. His latest graphic novel The Dancing Plague is no exception, made through a combination of burning drawings onto canvas and intricate embroidery, a tale of medieval mystics and a bizarre epidemic. It's got to be the first of its kind, although I haven't checked.

The algorithms of my social media feed can sometimes seem like a constant loop of homogenized mediocrity, it can get me down. Thank goodness for Gareth Brookes. Over the last few years I've seen Gareth make comics using lino cut, monoprint, embroidery and wax crayon etching. From comics about old ladies who see visions in the supermarket, silent psychedelic science fiction, suburban teen angst to erotic eavesdropped conversations on the bus. Something for everyone, really. There's wry wit, deadpan delivery, they are fun and horrific, silly and strange, but always interesting, always something new. His latest graphic novel The Dancing Plague is no exception, made through a combination of burning drawings onto canvas and intricate embroidery, a tale of medieval mystics and a bizarre epidemic. It's got to be the first of its kind, although I haven't checked.

Joe Decie: So this new book, The Dancing Plague, rather than me doing a big preamble, could you tell me about it? Pretend I haven't just read it. What's the story?

Gareth Brookes: The story is based on the true events surrounding a dancing plague that happened in Strasbourg in 1518. A dancing plague is also known as St Vitus’ Dance or Choreomania. It involved people being seized by the compulsion to dance for days or even weeks on end and it spread like an infectious disease, before long hundreds of people were dancing wildly for no apparent reason, often dancing themselves to a state of exhaustion or even death. This was not an uncommon occurrence in the medieval period, but the 1518 outbreak was the last and best documented of the dancing plagues.

The story is told through the eyes of Mary, who experiences mystical visions. Her life story is intertwined with the narrative of the dancing plague. I wanted to tell the story from an individual’s perspective and through her mystical visions I was able to try to present the mindset and belief system of a medieval person alongside the historical events that took place, and maybe even throw some light on why this bizarre thing happened.

I'd never heard of such a thing before, it's fascinating. There was a time, here in Brighton, where you couldn't walk through town without encountering at least one lindyhop flashmob or a silent disco walking tour, and they're pretty scary. But these dancing plagues, where d'you learn about a thing like that?

I first heard about The Dancing Plague form reading an article about dangerous dances. The well-known rapper Drake had just released a video where he jumps out of a moving vehicle whilst still doing a special dance to go with his song. Copycat Tik Tok-ers were injuring themselves as a result. The 1518 dancing plague was listed in the article as the tenth most dangerous dance in history (I can’t remember any of the others) so I looked it up, and immediately knew I wanted to draw it despite the number of crowd scenes involved.

I started reading more about medieval history which led me down a rabbit hole ranging across a millennium of time. I loved learning about stories like the romance of Ableard and Heliose, two of the greatest intellects of their time, which became a philosophical and spiritual romance after an unfortunate castration incident. Or the great scholar St Adrian of Canterbury, who travelled from North Africa to England, and would have been the first black Archbishop of Canterbury in the 7th Century if he hadn’t turned the position down (twice). I was especially fascinated by the phenomenon of female medieval mysticism, and got into Hildegard of Bingen and Julian of Norwich. But it was when I found out about Margery Kempe that I decided to make my character a mystic.

Yeah, fascinating. What was the deal with her? I don't know anything about Christian mystics.

Female Christian mystics were all the rage in the medieval period. These mystics lived precarious lives that depended on whether they could get support from Bishops and Priests. If they were verified by such a man, they often become an anchoress, and were walled up in a cell to live a life of prayer and holy contemplation for the rest of their lives. On the other hand, they may be called a heretic and imprisoned or even put to death.

Margery Kempe really broke the mould and got up everyone's noses. She was an unsuccessful business women and mother of fourteen who thought that her business failures were God’s way of telling her she needed to become a mystic. She travelled around dressed in white, calling herself a bride of Christ, she wasn’t shy about telling off priests or bishops if she thought they were corrupt or unholy and she was always having to escape from people who thought she was a heretic. She went on lots of pilgrimages, and was very unpopular with her fellow pilgrims because of her habit of crying and wailing for hours on end if anybody mentioned Christ's Passion. They banned her from the table or ran away from her because they found her so annoying. At the end of her life, she dictated all her experiences to a priest, who wrote it down in The Book of Margery Kempe which is [considered] the first autobiography ever written in the English language.

I totally love Margery Kempe, she quickly became the main source for my character Mary, along with another mystic Christina the Astonishing, who kind of had super powers. She could levitate, stay underwater for days on end and jump in fire, that sort of thing.

How did you go about researching all this stuff? There's some wonderful language in the book, some lovely swears. Are they historically accurate?

Absolutely accurate, I spent a lot of time on the swears! I reached out to some academics and asked if they’d like to help me out with getting the details of the book right. One who completely got what I was trying to do from the start was Anthony Bale who is a Professor of Medieval Studies at Birkbeck University of London. He helped me out with lots of details. When it came to the language, he advised me to draw from primary sources where possible. I read lots of Rabelais, who would have been alive at the time of the dancing plague, and who wrote Gargantua and Pantagruel, which is a hefty volume packed full of toilet humor, blasphemy, drunkenness and swearing. Also, the poet François Villon whose work is a treasury of imaginative insults. It’s a bit of a fine line though, if you make it too accurate sometimes a modern reader won’t understand.

And your drawing style too? The way you draw children as tiny adults, the crude perspective, it seems in keeping with the period?

Ha! Some of that’s just bad drawing I’m sure, but yes, in a lot of early medieval painting there was a hierarchy of scale, figures being more important the larger they were and the closer to the middle of a picture they were situated [in], often a building is depicted as just big enough for one person to stand in. At the center you’ll sometimes get a massive adult man Christ baby, it was considered heretical to ever think Christ was an actual baby. To complicate matters, medieval people didn’t really see their bodies as closed objects of a certain size, more as grotesque transformable forms. All this gave me a sanguine attitude to getting the drawings right. There’s one bit where I drew a young girl and a child running away from a lecherous priest. I accidentally drew the priest massive and the girl and child tiny, but somehow my attempts to redraw it just didn’t seem as medievally, or as distasteful, so I went with the original drawing.

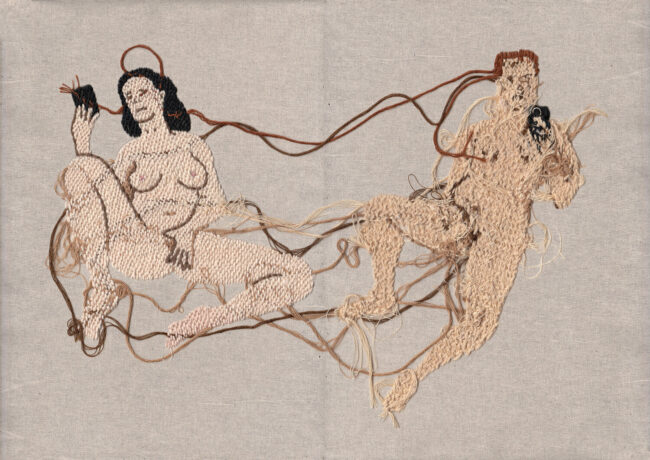

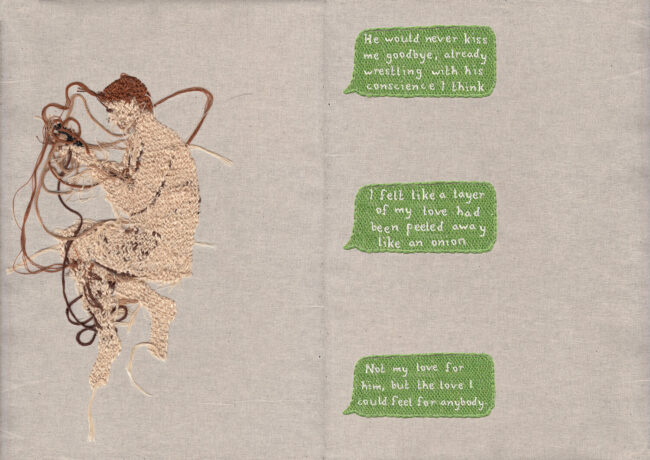

At the same time, I didn't want the artwork to be too similar to medieval art, I felt that it might hinder the readers connection to the characters. The embroidered part of the art is much more directly influenced by medieval art than the pyrographic artwork. I had a great time researching medieval demons and bands of angels in medieval manuscripts and paintings and translating them into stitch. I was looking at Bruegel for the pyrographic art and Bosch for the embroidery.

I was going to ask about that. Process talk. I’ve joked in the past that you’re never satisfied with the traditional way of making comics and always insist on finding a harder way of doing it. I mean standard comic drawing is labor intensive, but you strive to find ways that are even more so. The Black Project was lino cut and embroidery, Thousand Coloured Castles, wax crayon, literally the worst medium to draw with. And this one, it’s embroidery and pyrography? What’s the deal?

I’m not sure the mediums I choose are harder, really. Embroidery is more time intensive than drawing, but I’m not sure it’s more labor intensive, it’s very meditative, portable and sociable. It never feels as much work as drawing. Using linocut and crayon, you have to accept the result you get. You can’t rub anything out. It’s all about letting go and having physical material surfaces do the work. Artists act like digital drawing is quick and efficient but we all know it’s way more work, all that undoing because you don’t want to show a bit of vulnerability.

For me it’s all about the vulnerability and struggle of wrestling with these very physical processes, the creativity and unexpectedness that comes from not knowing what you’re doing and always being in danger of failing. I’ve heard people say it takes 10,000 hours to master your style or your line or something, but to be honest I think it takes 10,000 hours to become boring and mediocre. The moment you master something is the moment you stop being creative.

The other reason I use these weird materials is they carry meaning. I always seem to use processes that attack the surface of the page, scratching, piercing, burning, pressing, but these are also things that you can feel as a human body. I’m always burning or poking or cutting myself making my comics, on the other hand, the surface of an embroidery is a nice thing to touch. When I show at fairs people are always touching the surface of my comics, as if they expect to feel the embroidery. So, I guess I want the reader to have an embodied, haptic response to what I’m doing.

I don’t want it to sound like I’m against digital though, I’ve started using Procreate and it’s a great tool. I think the reason people like it is because it can do the scratches and splotches. I’ve noticed that some artists actually get more scratchy and splotchy using Procreate. It's ironic, having the digital facsimile allows you to embrace managed imperfection.

Before you've mastered a technique, it's time to move on, try something new, to keep it imperfect. So the goal with your work isn't perfection?

I’m not sure I’d know perfection if I saw it! For me it’s more about communication, and perfect artwork doesn’t mean perfect communication. I’ll give you an example; one of the first indie comics artists I was aware of was Jeffrey Brown. I really liked how he couldn’t draw very well in those early relationship comics like Clumsy and Unlikely. The line was awkward and uncertain, just like he was in the comics. As his drawing got better, he got a bit better at relationships. Nowadays Jeffrey Brown can draw really well, he’s got that whole Star Wars thing, and his style is really nice and developed. But if he went back and drew those comics now, they’d be crap. In fact, they’d be jarring because they wouldn’t communicate as well, you’d have less patience with the character’s neediness and passive aggressiveness.

The thing about comics is that they communicate through marks made by another human hand, that you can relate to as such. If the marks are perfect, how can you relate to them? They’re inhuman!

The whole digital replication of traditional techniques, complete with programmed imperfections, I guess is trying to convey this, the human touch. I've spent ages working on a digital pencil drawing of a pencil, just for my own amusement.

You mentioned Jeffrey Brown as the first indie comics you saw, what was your path into comics? I can't see any obvious influences.

I’d always been sort of into comics, but when my friend from art school Steve Tillotson started making Banal Pig Comic (for which I wrote maybe one story per issue), we started going to cons. There was always that one table at every con that sold Top Shelf or Fantagraphics books. I found out about Jeffery Brown, Dan Clowes, and maybe Seth during this time. But I’m sure you remember those days Joe, there was nothing. Nothing there to really get into. There weren’t any British indie comics publishers I was aware of, or indie fairs, or anyone writing about indie comics. It was only when The Web and Mini Comics Thing and the Comica Comikets started in the mid '00s that I slowly became aware of other people doing stuff I liked the look of. It was people like Matilda Tristram and Malcy Duff, who were doing really weird surreal little comics and not seeming to care whether anyone bought them or not. I thought that was very cool. Very different to the attitude I’d been used to from art school. Then people started putting on their own fairs and that was really fun. All of a sudden, we had this little UK scene. That was what really got me into comics, having a peer group of maybe a dozen creators, everyone seeming to be finding their way at the same time. Then I went to Angoulême in 2010 and got my mind blown, I saw what comics could be like, I found out about publishers like FREMOK and realized I could bring things I had been doing at art school like printmaking and painting.

I was lucky enough to get involved just as the scene was blossoming, a lot of crossover with zines, small press fairs. That's where I first got to know you, at those kind of shows. You could be tabling next to an aging anarchist poet or someone making zines about setting up community gardens. I liked that a lot.

I feel like you fostered some of that DIY energy, that community spirt. You've had a lot of involvement in the organizing of fairs and workshops over the years.

Yeah, I definitely did my bit! There was a year or two when I was heavily involved with the Alternative Press where I didn’t make comics anymore, just organized events. But I learned a lot from that, I think that it’s an important part of being an artist of some kind. I always go back to this idea of Brian Eno’s of ‘Genius’ and ‘Scene-ius’. The idea that there’s two types of creative energy, that of the individual and that of the collective. Any lasting bit of art whether you’re talking about 2000 AD or Duchamp’s urinal, had a network around it, not just of artists, but all sorts of people, feeding the ‘scene-ius’ of a particular place and time. I think that feeding that energy is the responsibility of all of us, particularly in comics where there isn’t any money or infrastructure. It’s like National Service for comics. I think that small press comics in the UK have gone up in quality to a staggering extent, but it’s becoming a thing where everyone's coming off an illustration degree now, and seeing small press comics and zines as a way to being ‘properly’ published by the micro publishers that have sprung up over the last seven or eight years. They don’t realize that all those publishers and fairs were put there by a previous generation as a way of reinventing comics, and it’s still running off that previous generation's energy. There is a certain responsibility for a generation of artist to go off and engage in different activities, and revel in the glory of doing something new and determinedly unprofitable, and not just try to slot into the ‘industry’. I think some of this DIY spirit will come back, part of the problem was that all the spaces we used to use back in the Alternative Press days got turned into luxury flats. Maybe Covid will mean more empty spaces to use?

Anyway, the mixing up of zines and comics really contributed to my artistic development. It taught me that some of the greatest works of art ever are cheaply printed zines with a print run of 20 that cost 60p. And that’s what they’re supposed to be. Not everything has to end up as a graphic novel. Only a few of us at those fairs had even been to art school which is unthinkable now. The idea of zines has become so co-opted, you see appalling things like zine workshops at the Tate that cost hundreds of pounds to sign up for, or zine competitions that cost a tenner to enter. Fuck that. Draw your own certificate of zine qualification if you really feel you need one. It will be more meaningful.

It worries me a bit that people think it essential that they study comics to get anywhere. Degrees, masterclasses. Dustin Harbin and I were talking to a young comics student who couldn't understand that we hadn't learnt comics, not in a professional setting. Not that I think professional study is a bad thing, just that the costs mean it will not be accessible to all.

I can’t imagine who I would have learned comics from, or what they’d be like if I’d learned them. I mean, I think its important to study the work of those that have gone before, and to respect their contribution, but it’s also important to decide that those people were full of shit, and that you’re against everything they represent and that your way of doing things will be different. At the same time, I have to acknowledge that I have been to art school, and that probably gives me the confidence to be able to say that. Maybe I’m being hypocritical, I make very arty-farty comics, and yes, I teach at an art school, but I really do believe, quite passionately, that anyone can and should make comics or zines and that those comics or zines can be valuable and important. It’s this weird attitude in society that says it’s not valid to make art unless you're a 'professional'. It’s not a standard we apply to many areas of life. You wouldn’t go up to someone growing vegetables in an allotment and go; “I bet you don’t make a living off of those vegetables. I bet you’ve never even got one of those vegetables accepted into a supermarket. You’re not a proper farmer. They’re just vanity vegetables.”

Ha! It is a weird thing, being a "professional". I distinctly remember a change in the way some people talked to me once I'd been professionally published. I wanted to ask about that, that jump from being small press to being big time published. Personally, I found it left me feeling odd, like there was some change in expectation that I did not like.

Yes, some people's attitudes do change. They’re suddenly very impressed by essentially the same thing you showed them a year ago. You get teaching, and get asked to go on podcasts or panels, and you feel like everyone wants to know the secret to your tremendous success. But the secret is that there’s no difference between what you’ve been doing all along and what you’re doing now. The money’s not much more, the process is the same, you still have to sit behind tables at cons and not sell anything.

At this point I value the two sides of my work equally. Between making graphic novels I make small press stuff, it allows me to experiment and have fun. Besides which, there are plenty of ideas worth making that can only exist as weird little zines. Take Threadbare for example. No publisher wants to publish my fully embroidered, semi pornographic zine about a conversation I heard two elderly ladies have. And if it was ‘properly’ published, something intimate and indefinable would be lost. Other stories have broader appeal, and need to be longer and more developed. Those projects need a publisher to help edit, and to give the book the production values it needs and get it distributed so that it can be the best thing it can be. But whenever I make a small press book, some people act horrified, like I must have been dropped by my publisher and I’m back where I started.

So, in answer to your question, I don’t really think about being ‘professional’ anymore, it’s an idea that other people have. The thing I probably most struggled with is the fact that I’d always done comics as a ‘hobby’ after work, and that now I was doing it all the time, I needed a new hobby. I tried brewing beer for a while, or playing guitar, but in the end, I realized comics is still my hobby, it’s just that now I do it all the time.

Brilliant, I'll let you get back to it then. Thanks Gareth.