Here’s a hypothetical. There is an upcoming massive Olympics-style battle royale between each country in the world’s single best cartoonist.

A history of publications will be taken into account, but this cartoonist must be making their best work right now, constructing their showpieces this very day. This contender should obviously have impeccable artistic chops and draftsmanship skills, but that’s not all. The nominating committee (which in this hypothetical, I have a prominent seat on) will also be considering the cartoonist’s mental fortitude, tenacity, and ability to adapt. The committee will be looking for diversity and distinction in terms of personal style. This challenger must also have no end of ideas. My choice to represent America is Derek M. Ballard.

Ballard has been producing a singular body of work for over two decades, congealing his keyed-up characters with idiosyncratic angular anatomy into an often-unforgiving neon science fiction setting. Oh yeah, these comics are also funny. Along with all his seemingly countless unpublished or abandoned strips, pages, and pin-ups, Ballard has released two issues of his one-man anthology Cartoonshow since 2011 (featured as a “Notable Comic” in The Best American Comics), the unearthly Ghoulanoids #1 in 2015, and Choreograph Volume One in 2018. All of these give a platform to Ballard’s creatures who slyly prowl or kineticaly clunk around his pages, and that is probably what attracted him to animation producer Pendleton Ward. Since 2014, Ballard has been a storyboard artist, writer, character designer, and title-card creator for two of Ward’s shows: Cartoon Network’s Adventure Time and Netflix’s The Midnight Gospel.

There is a quote by singer/songwriter Steve Earle that goes, “I’m into pain and joy and the in-between doesn’t interest me.” Nothing better describes Ballard’s recent comics, which have veered sharply into autobiography. For the last year plus, his pages have become introspective (amazingly without losing any of the unflagging energy from his previous work) and have explored fatherhood, relationships, and his peculiar past. We talk as he is becoming a more prolific cartoonist and his career takes a turn inward. - RJ Casey

RJ CASEY: Are you good to interview tonight? I know you’ve got a sick kid at home right now.

DEREK M. BALLARD: Oh, yeah.

What’s going on?

Well, this is par for the course. I’ve been doing this for 20 years, you know? But the thing is, my eight-year-old developed an inflammation last year, so he had to go to the hospital and get on a morphine drip. But earlier than that he had COVID and was on a breathing tube.

Jesus.

His immune system was lowered and then that happened. But now it started flaring up again and, man, no doctors can tell me anything straight. They’re like, “We’re waiting for test results.” So, tomorrow, if they don’t tell me anything more, I’m just going to go back to the ER. I’ve been giving him two MLs of Oxycodone the past two days.

That’s the only thing they’ve prescribed?

No, no, no. There are three topical ointments. One steroid, one antifungal, one anti-bacterial. And then an oral analgesic to help with pain. But it’s just me. I have a daughter who’s 19 and she works and I have a 12-year-old, but the eight-year-old won’t let anyone else help him. So I just gave him a warm bath with baking soda. I can’t believe this is my Comics Journal interview. [Laughter.] You get it. How many do you have?

I’ve got two kids. A three-year-old and a seven-month-old.

Wow, you’re a dead man walking.

I already feel that. This three-year-old is already challenging me.

How old are you?

I’m 34.

OK, OK. You’re still youthful. [Laughter.] I was 22 when I had my daughter. Everyone I know waited until they were like my age to start having kids. I’m glad I did not do that.

How old are you?

I’ll be 44 in a couple of weeks. Not that old, not that young. Is this interview going to be a hatchet job?

No. [Laughs.]

I don’t need help with that. I do a good enough job myself. But do what you’ve got to do. You Comics Journal people are all mean.

Sure. [Laughter.] You grew up in Mobile, Alabama.

You said it right. Yes, Mobile, Alabama. Most people pronounce that wrong. How did you know how to say it right?

I don’t know. I read books. I probably heard someone say it in a movie or something.

All right. [Laughter.] I’m suspicious.

What was your childhood like?

I grew up in a FEMA trailer at the end of a dirt road. In the ’70s we lived in a different trailer, but Frederic was a big hurricane that hit Mobile. It rolled the trailer like a log. We weren’t in it.

Oh, wow. How old were you when that happened?

I was about two. Maybe one or two. I have a memory of going back to the trailer and seeing everything torn up. Then the trailer that we grew up in, we got it from the government. It was at the end of a dirt road and it was — Mobile is weird because it’s all kind of urban and rural at the same time. There are a lot of factories. So, the dirt road was a dirt road in name only. It was like a series of craters. There was an empty, wooded lot in front of us and a drug dealer lived there in a plastic teepee.

That was his permanent residence?

Yeah. He used to grow vegetables and give them to us. My parents were like, “He’s a drug dealer, but he’s the nicest person around.” [Laughter.]

What did your parents do?

My mom was a homemaker for a little while. Then she would just have odd jobs. My dad always worked at Scott Paper Company, which was a huge company in Africatown, which is a little neighborhood in Mobile. You can see stuff on the news recently about Africatown and it’s a shame the way they treat it. It’s the last place slaves were dropped off in the United States and it was founded by them. The whole neighborhood has been completely raped and destroyed by industry that hasn’t been regulated. It’s gross. It’s a gross place now because the factories do whatever they want. They just ruined it. I don’t like that place. I don’t know, maybe I shouldn’t say this.

Did you have siblings?

I have one brother. He’s seven years younger than me.

How were you first introduced to art?

Definitely by cartoons on television.

Which ones?

The Flintstones, The Beatles cartoon show, Charlie Brown. A lot of the stuff that was on PBS like the interstitial things that were on Sesame Street or Electric Company. I still like those. But growing up I was watching all of these on a black-and-white TV.

Then did you start drawing to see if you could recreate those characters?

Yeah. Since my dad worked at a paper company, he would bring home cases of mis-cut paper. I would just sit there and watch cartoons and draw. My mom always tells a story of me being 18 months old and drawing. Just watching TV and drawing.

It was that natural for you right away.

I’ve always done it. I’ve always been the drawing guy. I’ve always loved it. I need to learn to do it faster. [Laughter.] Everybody says that, I guess.

How long did you stay in the FEMA trailer? Was that for your entire childhood or was that more of a temporary residence?

I was there until I was 13. Then my parents got a house, but shortly after that, they got divorced and we lost the house.

Where did you move after that?

My grandparents owned a trailer park that they started in the ’70s. My grandfather was a great guy. He was a really nice guy, but that place was a slum. What he would do was find people who couldn’t get in anywhere else or rent anywhere else. He would let them rent a trailer that he had on this land. The family used to critique him for letting some of the people in but he always said, “If I don’t help them, then who’s going to help them?” When I was a kid that annoyed me, but now I see it as a noble, nice thing. He was unique because he was an evangelical minister who also owned a trailer park, but also was an extreme leftist. He would be like, “I read the Bible and all this Republican stuff doesn’t make sense.” His fellow ministers were his friends and they would have these debates all Sunday afternoon and they would leave saying, “We can't beat him. He’s right, but we don’t agree with him.” He used to say shit like, “I just don’t see how you can be a Republican and expect to get into heaven.” [Laughter.]

I feel like religious leftists used to be a little more prevalent. Like the activist nuns.

Yeah, stuff like South American Liberation theology. It’s inspiring, you know? We moved in there and what happened is, in the ’80s — my grandfather got used to dealing with drunks. There would be a drunk who would have a wife and kids and my grandfather would let him stay there. But stuff started coming in like crack, meth, and other stuff. My grandparents did not understand how that stuff worked. They didn’t drink or anything and just thought, “This dad has a problem and we think it’s some kind of drug, but we’re going to help him.” They just assumed they were going to be like an alcoholic. But they weren’t. In the ’90s, it got far more intense. It got to the point where people started blowing up his trailers with meth labs.

While you were staying there.

Oh, yeah. Oh, yeah. It got so ugly out there.

Due to your grandfather, I assume you grew up religious.

Well, we didn’t go to his church. We went to our own church, but I had to go Sunday morning, Sunday night, and Wednesday night. When I was about 12 or 13 I was reading a lot and just decided I didn’t believe in God anymore.

What was the catalyst for that decision?

I started reading about biology and there seemed to be a design there that I thought supported evolution. That was one thing — I got into biology and was reading National Geographic. Also, a lot of the people I went to church with, I just thought they were awful. I was mad. Now I’m not so mad about it. If you want to believe in God, go for it. But when I was a teenager I was mad about it. I just saw how the men in the church could get away with whatever they wanted. I saw the moms and the kids and what they had to deal with.

How much time did you spend in your grandfather’s trailer park after the drugs started coming in?

I moved out on my own when I was 18, but you’ve got to understand that in that entire city, there was nothing good. That stuff was everywhere. When I was a teenager, the girlfriend I had, her mom got into a car accident and got a $100,000 payout and became addicted to crack. My girlfriend didn’t know she was addicted to it and then it became an insane fiasco after that. I got exposed more and more. At school, kids were dealing with their parents. My grandfather was dealing with those people. My girlfriend had bounty hunters coming after her parents.

How did you escape that?

I moved to Gainesville, Florida, when I was 30. That’s how I escaped it. The woman I was married to for so long, we worked so hard to get her through nursing school. Then she ended up getting a job at a hospital in Mobile in a burn unit. She was mainly treating people who had been cooking meth and got burned. At that point, I couldn’t do it anymore. I had to get out of there. We worked forever to get her through school and we could pick between Gainesville, Florida, or Austin, Texas, to do travel nursing. That’s how we escaped. Gainesville is a nice, clean little place. Florida I have other opinions about, but Gainesville is a nice, little oasis. When I was 30, I finally got away from Mobile.

I want to go back here. You said you were drawing since you were 18 months old, but when did you know you were good? When did you know that you were more talented than your peers or classmates?

When I was in kindergarten, they went around the class — it was Miss Cathy’s class — and she asked every kid what they wanted to be. The boys were like, “firefighter,” and the girls were like, “nurse,” “Sunday school teacher”. She got to me and I said, “I want to be a cartoonist.” I remember she was like, “Uhhh... OK.” [Laughter.]

How did you even know what cartoonist was in kindergarten?

I remember I got into an argument with another little girl at my table because I drew a sheepdog and I didn’t draw his eyes. I drew the hair in the eyes because I’d been watching those Chuck Jones cartoons. She was like, “You didn’t draw the eyes. He doesn’t have eyes.” And I said, “He does have eyes!” I think I went home and talked to my mom and she’s like, “That's how that cartoonist drew it.” I think I went back to that girl and said, “Yeah, a cartoonist draws it like this.” [Laughter.] In elementary school I would draw stuff for other kids for a quarter. I’d enter poster contests and win. I did that all the time. Then in sixth grade, the school I was at just got too bad. There were so many fights and my mom went to the school board. She was like, “Hey, can we get somewhere else?” They said, “We’re opening this school for the creative and performing arts. He can try to get in, but he’ll have to show a portfolio.” I got in.

Do you remember making that portfolio? Did you collect things that you already drew or did you have to draw all new material?

There were just stacks all over the house. My mom just grabbed stuff, you know? I think at that time I was probably really into Mirage Studios. There was a used bookstore that had just a ton of black-and-white comics like Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and Gizmo and the Fugitoid. You know that weird stuff? They all smelled like cigarettes. [Laughter.] I was like 12 buying that stuff at this used bookstore.

Was that your first exposure to comic books?

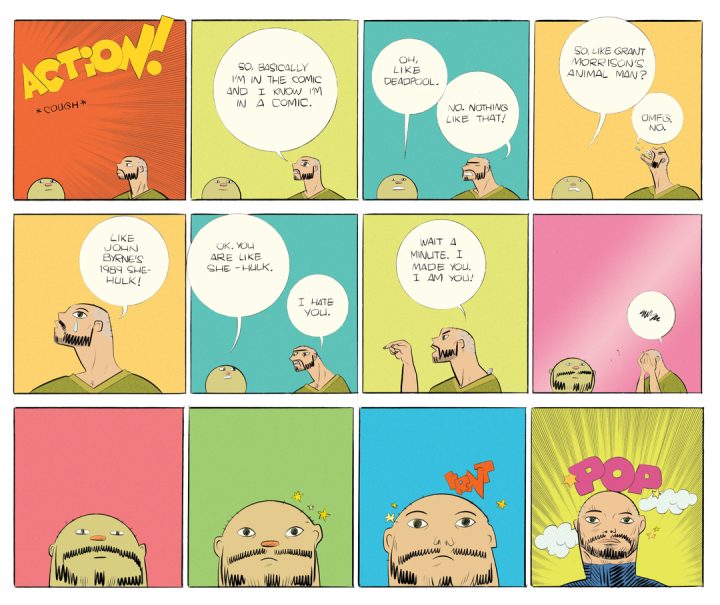

Prior to that, I really got into John Byrne’s Sensational She-Hulk.

Wow. OK.

I loved the drawing. [Laughs.] She-Hulk was like, “Isn’t it weird that I’m in a comic book?” I was like, “It is weird! And I’m reading you.” [Laughter.] Then I just started looking for more stuff.

It blows my mind that of all the comics, you found She-Hulk first.

They sold it at my grocery store. Yeah. It was the first issue.

I can picture the cover.

She says something like, “I’m going to rip up your X-Men.” I think I tried to read X-Men before and I couldn’t do it. I didn’t know what was happening. So I was like, “Yeah! I don’t care about X-Men. Rip them up!” I was looking for the weirdest stuff I could find on the newsstand. There were a lot of weird NOW comics. There was Speed Racer. They did Ghostbusters comics. It was just trash, but some of the stuff they had was bizarre. I really liked the weird black-and-white stuff and then I found a comic book shop in town when I was a few years older. I’d go in there and just dig through the dollar bins. I found Underwater by Chester Brown. I found a run of Dark Horse Presents with Moebius and Jodorowsky. I was probably 14 and had no idea who this Jodorowsky guy was.

In one of your more recent comics, you make reference to being locked up as a teen. When did that happen?

I was probably 14 or 15. What happened is... It’s kind of embarrassing for me to talk about this out loud. I don’t know. I don’t mean to make him look bad, but years ago I was telling Ben Marra about this and what happened — I ran away. I was sleeping under a bridge for a while and the cops picked me up and just took me and put me in a juvenile detention center. Ben was like, “They can’t do that!” And I was like, “But they did.” He said, “Man, they can’t do that.” I realized that for most people, that's the first thing they think — “that can’t happen.”

He's Canadian.

I love that man. I love him, but it was at that point where I was in different cities like New York — when I got to New York, I’ve got to watch my mouth because I start saying stupid shit like this. People are always like, “What are you talking about?” “Oh, right. This is not a nice topic.” It’s depressing.

So, at 14 you decide to run away. Why?

My dad was physical at home. He was physically abusive. One day I went to school at that creative and performing arts school and had a mark on my face. Somebody told their parents and then DHR [Alabama Department of Human Resources] came up there. DHR interviewed me and then they went and talked to my dad. They came back the next day and said, “He seems like a good, Christian man. I don’t think that this is worth investigating.” So then I had to go home to that.

And your dad knew that someone told and everything fell on you.

Oh, yeah. Yeah.

Did you pack anything up or did you just leave?

No, I packed up. The school was downtown, so I left from school.

You said you stayed under a bridge?

Yeah.

A cop saw you patrolling or did someone report you?

I had been going to a gas station nearby to use the bathroom and I think they called.

How long were you there under the bridge?

Just a few days. I’m going to do a story about that one night because I got to Strickland Youth Center and there was this guy there who was like glowing bright red. He was this white dude that was sitting there waiting to be processed. He was glowing — I could just see energy coming off of him. This guy next to me was like, “Dude, you know who that is?” I was like, “No.” A few weeks before, it had been in the news that a pizza delivery kid got gunned down in a drive-by. It was his brother. At the sentencing for the guy that shot him, this kid — the brother that was glowing — jumped over that wall that separates everybody from the judge and lawyers. He jumped over it, jumped over the bench, and attacked the guy in the courtroom. They had to drag him out and I was there with him that night. I don’t even think that man blinked.

What was this Strickland facility like?

Shitty. Really plain, no frills, cinder blocks. Do you know what VCT tile is? It’s cheap-ass tile.

Did anyone attempt to get you out or vouch for you, or was that not even in the question?

I don’t really know. I don’t know. The authority figures were impenetrable to communication. I still run into that now. If people don’t want to hear something or don’t want to believe it, they’re not going to. I learned that there — no one is going to hear you if they don’t want to hear you. Most people there would say stuff like, “I don’t get paid enough to do this.” I’ve heard that a million times. I was there for a while and then I got sent to another place that was like a psychiatric facility.

How long were you at the juvenile detention center for?

A couple months.

And then they transferred you.

Yeah.

What was the reason for the transfer?

I think somebody was trying to be nice by not sending me straight home. Maybe they thought that at the psych place, something could get worked out.

What was this new place like?

A lot of kids there were on drugs. I didn’t do drugs, but I learned a lot about them and I met a lot of people there who, when I got out, I had a lot of interactions with. [Laughs.]

Seeing them around town?

Yeah, yeah. But at this place, on any given night, there would be like straightjackets and they’d thorazine somebody. Somebody would be freaking out and they’d put them down and strap them to a bed. There was a lot of people acting out, but I was just quiet. I stayed on the “good” list and got extra rewards like extra apples or Cheerios. I’m embarrassed to talk about this. Making a comic about it is different.

Why are you embarrassed by it?

I don’t know, I don’t know. No good reason. I just feel it.

How is talking about it different from putting it down on paper?

You know, it took me a long time to do anything autobiographical. Especially after everything that’s happened to me over the last few years and then COVID, now I feel like it would be completely dishonest if I wasn’t talking about this and putting this stuff down on paper. I got to a point where I just had to. Hearing myself say it — you know what it is? When I make a comic about it, I can make it funny. Right now, I sound emo. [Laughter.]

How long were you in this second facility?

Probably five or six months.

You were locked up for a better part of a year of your life. Did you have any communication with your family at all during this time?

At the psych place, there’d be a weekly family meeting.

Were you drawing at all during this time?

The whole time. The whole time. I was drawing extra.

What were you drawing?

At that time, I was pretty angry —

I can’t imagine why. [Laughter.]

I was drawing a lot of crazy stuff. People there would be like, “Hey, if I gave you this apple, would you draw something for me?” I would always say, “Yeah, sure.” A big thing was drawing things for other people to send to their girlfriends because we could send letters. “You think you could draw a heart or rose that I could send to my mom?” There was this guy Jamie and he was at the psych place because he was on meth or something. When I got out, I was hanging out with some people and we ended up at his house. He was doing OK and that night he said to me, “I want to show you something.”

Uh-oh.

This was years later, but he had this dragon that I had drawn for him on his wall in his room. I’ll never forget it.

That’s really cool!

It made me feel good and he was somebody that ended up being OK. There was a guy who was my roommate in the first place and his name was Mike. He pronounced buffet with a hard "t". [Laughter.] He told me, “We’re going to start bare-knuckle boxing at night after lights-out.” [Laughter.] I was tall, but I was little and wiry. He was tall too, but he was chunky. He was a big dude. I learned that when you’re pounding on his chunkiness, he can’t feel it and it’s hurting my wrists.

You actually went through with this boxing?

Oh, I had to. I had to. He was making sure to hit me in places where the bruises would be covered by clothes. One night I got really mad. I got really mad and went, “OK. I’m going to plan.” I decided to start connecting with the bony parts of his face.

A winning strategy.

I laid him out. He sat up and said, “Man, you’ve got spunk... I don’t think we should do this anymore.” [Laughter.]

Good!

It took weeks! I’m not trying to sound like a tough guy because I’m not. But that whole bullshit.

I can’t imagine living through this for nearly a year and then just going back home and going back to school like normal.

Well, now I knew how to fight and knew people who were into bad things. Also, now I knew how to not get into trouble.

You’re in high school now at this point. Did you graduate high school?

In 1996, yeah. During the last part of high school, I was a machinist at night. I got enough to buy a car.

What were you making?

There’s a place called Southern Fasteners that was at the state docks in Mobile. There was this guy there who could do stuff to nuts and bolts faster than the machines could. So they’d send him home with truckloads of stuff and he had this rickety metal shop in his backyard. I’d help him. I’d be using the lathe, the grinder, cutting things. Sometimes the bolts would be minuscule and sometimes they’d be for like the navy, so it would be cutting a bolt the size of my thigh. Sparks would be flying all over me. That was during the end of high school. I worked hard jobs and I knew that I wanted to not do that, so I got a job at a bookstore. That’s when I was able to rent a house downtown with a friend who I worked with — a girl from the bookstore. I just did a comic about her. She died... She was a college kid and had been going to Tulane in New Orleans. She was going to take a year off and she was from Mobile. She knew a lot about music and I knew a lot about other kinds of music. We just sat around and talked about music all day. She got a record store job and some guy she worked with — I remember it exactly. “There's this new thing called Oxycontin. It’s a pill so it can't be that bad.” I was like, “I don't know. I don’t think so.” I just had a feeling. She struggled with that for the rest of her life.

I know I asked about escaping earlier, but how did you avoid drugs? How did you survive this? They were seemingly everywhere.

Right, which is to say I didn’t entirely. But a lot of stuff makes me sick.

Your natural chemistry or body’s reaction saved you.

Yeah. My great-grandfather, he was orphaned when he was 10 and had to go work at a farm. He lived to almost 100. A cool guy. We would ask him about the old days and one time we were like, “How did you never become a drunk? Everybody else was drinking.” He was like, “It makes me throw up immediately.” I swear to God, I got his genes. There’s some stuff my body just does not like — pills, drinking. Now, I used to smoke a lot. Also, if it messed with my drawing, I didn’t want to do it.

OK, you’re conscious of that.

I skipped a big part of high school. I had different friend groups. There was one group where we were getting into bad things.

What do you mean “bad things”?

Running around, selling this, delivering that. Breaking into this place or that place. Then I had a different group of friends who were all in bands. I’d go to a lot of shows and the people there, if they needed something or wanted to know how to get something, they came to me. One of the bands was called XBXRX and they became huge and moved to Oakland. Bands would come through like Bratmobile and come and hang out. It was a cool scene, but all those people moved and the people who were still there — Oxy came through and a lot of people got on that. That was a big part of high school that I left out telling you. At that point I was really thinking that I’d keep drawing but there’s no way I could do it professionally. That’s when I became a machinist. I needed a car, I needed to put gas in the car, I needed to help my mom.

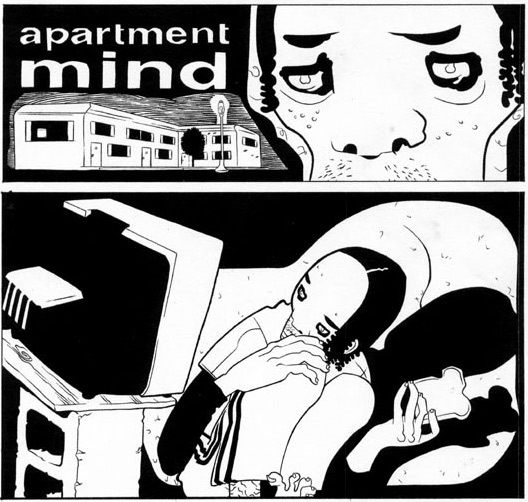

Your earliest work I could find was from 1997 called “Apartment Mind”.

Right.

Was that your first attempt at drawing a full comic story?

Yes. When I was drawing that I used to get the Fantagraphics catalog for free. They’d send it if you just asked for it. I never had money to order any of the books, but I’d look through the catalog. Then, one time, I had enough to order that Modern Cartoonist pamphlet by Dan Clowes. I ordered that and read that and read that. He was talking about things like, “Watch a film and then look at a non-moving image and see how it falls apart when the image begins to move.” I could rent movies then, but I couldn’t get the good comics. All I had was the Fantagraphics catalogs. So I started watching Hitchcock and anything that I could get my hands on where I thought that there was a visual element being used in a unique way to further the plot. Anyway, “Apartment Mind” was connected to me and I don’t know if it made sense to you.

I’ve only seen the first page. How long was it?

I never finished it. I did about 10 pages and I just put it away. I thought, “Why am I doing this? What am I ever going to do with this?” That was before I knew about self-publishing or minicomics or anything. I’m still proud of it. I like it. I’ll tell you the truth — I keep thinking about going and finishing it. I’d love to do that.

What is it about?

I was very young, OK? [Laughter.] There were a lot of things I was trying to work out in my head. At that time, I was reading The Myth of Sisyphus by Camus and all that stuff, you know? Man, for a lot of this stuff — I’m not a college-educated person so I don’t know if I’m reading things correctly but at this point I just want to read it the way I like and understand it the way I like. I thought I could do something close to German Expressionism and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari or Nosferatu, where the environment and the forms around the character exist to express things going on within the character. I was a kid and thought maybe I could do something like that. “Maybe this apartment is his mind and his outlook on the world. He needs to overcome that and get out of his own head.” The television was his eye into his deepest thoughts that he’s fixated on. Whatever. That’s what I was doing. [Laughs.] I was 18, I don’t know.

I can definitely still see hints of German Expressionism in your art today. Some of the harsh angles and themes in your work are not totally unlike George Grosz drawings. When were you first introduced to that particular movement?

I don’t know a lot about it. Most of what I know comes from movies that I could rent at Blockbuster or what they had at the library. I have big gaps. When I look at George Grosz stuff, it’s wonderful. But, like I said, I was digesting what I could get my hands on at that time. Movies had the biggest selection. The library was just OK.

After this comic from 1997, the next piece I’m familiar with — and the first place that I saw your work — was the Root Rot art anthology that Koyama Press put out in 2011.

There’s something in between there where I started doing comics again when I became a dad. I’ll tell you what it was — when my daughter was a baby, we lived in public housing behind the university. My wife at the time was in nursing school and I worked and took care of my daughter. I was able to use the university library. I’d go down in the basement and they had all these books by William Steig, James Thurber, Charles Addams. All that shit. I’d just sit down there while my daughter was taking a nap. I’d have her in the stroller and I’d sit down there and read.

Do those artists speak to you at all?

Absolutely.

That’s interesting because those are people who don’t seem to inform your work whatsoever.

Well, I can appreciate it. I don’t want to emulate it, but I liked that it was so different. Why would I want to look at the same stuff all the time, right?

Sure.

I ran into a guy down there in the basement a couple of times who was looking at the same books. He was from Mississippi and told me once, “I draw cartoons.” I’m like, “Really?” He said, “Yeah.” We started talking and I kept running into him. He came up to me one day and said, “I just sold a cartoon to Hustler.” I didn’t know Hustler had cartoons! I said, “Really?” He said, “I made $180.” I went, “What!” I’d seen his art and I could draw better than him. No offense.

Do you know the name of this guy?

I don’t know! I think he only sold cartoons maybe once or twice. I got the info from him because I was working as much as I could to take care of our family. We were barely making it. I was like, “If I could just draw one gag cartoon and send it to Hustler.” I tried and I never heard back from them. So now I had these stupid, stupid cartoons with naked women. I’m actually pretty good at drawing that.

This was in 2000? 2001?

Maybe a little later than that — 2002 or 2003. This is really what got me to be able to get back into comics. We were given a computer — a church gave us an old computer and we had dial-up internet. That’s when I started looking at The Comics Journal message board. I never really posted, but Danny Hellman said something about Screw magazine. I clicked the link and Danny Hellman got me hooked up with Screw. And now I’ll always have a stupid blow-job comic that was published as the cover for that magazine. [Laughter.] What I would do every Saturday is draw and the computer I was using had Photoshop on it, so I learned to use that. One cover from Screw would pay our rent. We were in public housing so the rent was $250 a month for a two-bedroom house. It was a horrible neighborhood, but I was doing it. “Saturday is the day I draw.” I just kept doing that.

How many Screw covers did you do?

I don’t know. Five or six.

This had to be near the end of Screw, right?

Really near the end. I know Molly Crabapple did one cover around that time. I remember back in the day, I was chatting with her on the internet somewhere about it. I was like, “I can't believe we’re doing this. Can you?” And she was like, “Yeah, I know. I’m eating ramen right now. This is crazy.” But after Screw folded though, the art director or editor there named Kevin Hein, he kept doing other magazines. He would call me up and I would do stuff. Their business model was the back half of the magazine were just ads for sex workers. Craigslist killed it when that came out. But Kevin, he was from back in the day. Do you know the whole history of Screw and all that?

I actually do know a little bit because I’m a huge Spain Rodriguez fan and he did some work for them.

He was doing some at the same time I was! RJ, I thought I was the hottest shit on Earth. [Laughter.] “Yeah, I’m published by the same people that publish Spain Rodriguez.” I can’t even touch that man, but I was still proud of that. I think in the late ’70s or early ’80s, John [Holmstrom], the Punk Magazine guy, worked with Kevin and they’d go and get the Screw magazine stuff printed and scanned and since they knew the people there, he’d go and get Punk printed on Screw’s dime. Kevin was an awesome guy and helped me out a lot. They helped me through Hurricane Katrina because a tree went through our roof at that time and they kept throwing me work. After that, I just kept drawing whatever I wanted and put it on the internet.

You coined the term “post-eroticism” to describe your art. What is post-eroticism?

It was a stupid thing that I thought was funny that I came up with because I had been drawing all that stuff for Screw. I just felt like I had more naked women drawings in me, but I wanted to do artsy stuff too. It’s a joke that I’m still saying. [Laughter.] Back then, a lot of indie guys were not drawing sex stuff. It was frowned upon. I think that’s really come around since then. Now everybody’s doing it and good for them. Back then, I told people that I liked Guido Crepax and everybody I knew — and these are people you know — they were like, “That work is creepy. He’s a creep.” Then Fantagraphics puts out all this stuff. Finally!

Going back to Root Rot —

Annie [Koyama] was nice enough to put me in Root Rot. Annie has done so much for me and my family. She got me to my first festivals.

How did she discover your work?

I don’t know. When I went to New York for the very first time, I met Michael DeForge and Michael was like, “I’ve liked your drawings for a while.” I was just like, “I have no idea how you know me or have seen those.” [Casey laughs.] I think it was just me putting stuff on the internet, you know? This was pre-Tumblr.

Piecing everything together here — after “Apartment Mind” in ’97 you keep drawing for fun and don’t attempt to publish anything else until Screw comes around?

Exactly. I still had the “Apartment Mind” pages — this is a funny little story. They are 18 inches by 24 inches, so I went to a blueprint place and got them scanned. I put them on a thumb drive. The only publisher online that you could submit electronically at that time was NBM. I sent it to them — all the pages that I had — and Terry Nantier, the publisher, emailed me. He was like, “I love this. Let’s do it. I’ll give you $1,000 up front.” I was like, “What?” [Laughter.] He ghosted me.

Really?

Yes, he did. [Laughter.] At that time they were publishing porno stuff by Brandon Graham, I think.

You do the two pages in Root Rot and around that same time you must get in with Youth in Decline because you’re in Thickness #1.

Right, right.

Did you meet Ryan Sands through Michael DeForge?

I don’t remember the first time I met Ryan. It had to be in New York. It had to be Michael. So, in New York, I ended up hanging out with Michael, Ines [Estrada], Lala [Albert], Wowee Zonk, and Ryan was around. Alex Degen was there. I did some good minicomic stuff with Ryan but the Thickness thing I’m really not happy with.

Why’s that?

I’ll tell you exactly what happened. When it was time to work, a stomach virus went through my whole family and I was the last man standing. At that time, I think I had two little kids and a wife. They were all puking, dude. They were all puking. I’m telling you this graphically because you’re a dad. At the end, I got sick too. I had to stay home with the two kids always because my wife, at that time, was the breadwinner and a nurse. We were in Gainesville and she was working at a huge hospital. I was puking in a bucket and cleaning up after two kids. We had one car and I had to go back and forth to pick her up. But I had committed to doing Thickness. I was drawing that with a bucket next to me.

The ideal atmosphere for drawing porn.

There’s nothing sexier. [Laughter.] I can’t even look at it. Johnny Negron is in it and, at the time, I loved that guy. I was like, “I’m going to really try to do something good,” but, you know, at least I can say I finished it.

Do you have issues finishing projects?

I did. But now, not so much. I also know my limitations now. But for years... This is kind of an intimate detail, but the person I was married to for like 20 years who’s just gone now, she would always be at work or gone doing something. She always had to go do this or go do that and she made me feel like, “I’m an independent woman. I want to have a career and I was already planning on doing this before you got me pregnant.” I was like, “Of course. I’ll support you,” and I kept supporting her and helping her. What she was doing was really paying off and she kept rising up through the ranks and getting accolades. But, then on the other side of that, I felt like she became much different and then started to judge me because I was making no money. But I was doing everything else. Everything else. I made her breakfast, lunch, dinner. If I was like, “Hey, can I have this Saturday to draw this,” there would be an argument and I can look back now and see that a lot of stuff was sabotaged. I probably could have gone on Adventure Time full-time, but she talked me out of it.

Other than that, she sabotaged things in what way?

[Long pause.] This is really personal, but I’ll tell you. So, after the fact, I find out that she’s sleeping with doctors at work while I’m at home with babies. So, there you go. She’d be like, “It’s going to be a late night.” And it was like, “You told me I could have tonight to draw this.” She never — just watch the episode of Adventure Time I did where there’s a character like me. ["Nemesis": Season Six, Episode 15] That was how it was all the time. Even though they had a mom, she was just never there. I thought it was for the greater good and she was working. Guess what though? Some people are shitty.

I asked about completing projects because I think that you’re a really interesting cartoonist in the way that you are a straight-up world builder, but you seem to be done with those worlds you crafted fairly quickly. Does that make sense?

I think so, but what do you mean?

While I was rereading your available work, I was thinking about the Cartoonshow world, the Ghoulanoids world — you seem to have everything invested in these concepts and groups of characters, but the series always ends after one or two issues. You move on to another project.

I have no interest in continuing them. They are like art pieces to me. I like [Yuichi] Yokoyama a lot. I love him. I’m not him and not trying to be him, but I love him. Everything is there for that one piece of art. I don’t have any interest in being like Tolkien or something like that.

I don’t mean that as a criticism either, but a lot of cartoonists could probably spend their entire careers attempting to build a fully realized world like you are able to. They could spend years playing in that world, but you seem to easily discard it.

Right. I enjoy work by people like that and I’m not taking what you’re saying as a negative. I like what you’re saying. That’s how I feel about it. There are other people who will do that better than me and I know that they’ll do that better than me. I always feel like I want to do something different.

Would you say that you’re a restless artist?

Absolutely, but in what way? [Laughs.] Like do I never feel like I can stop or want to stop? Yeah, definitely. I like doing different creative, odd, and varied things. But it comes down to me getting bored. If I sat down to do a long story, I’d get bored.

Do you have a traditional graphic novel in you? Or are you just uninterested in that form?

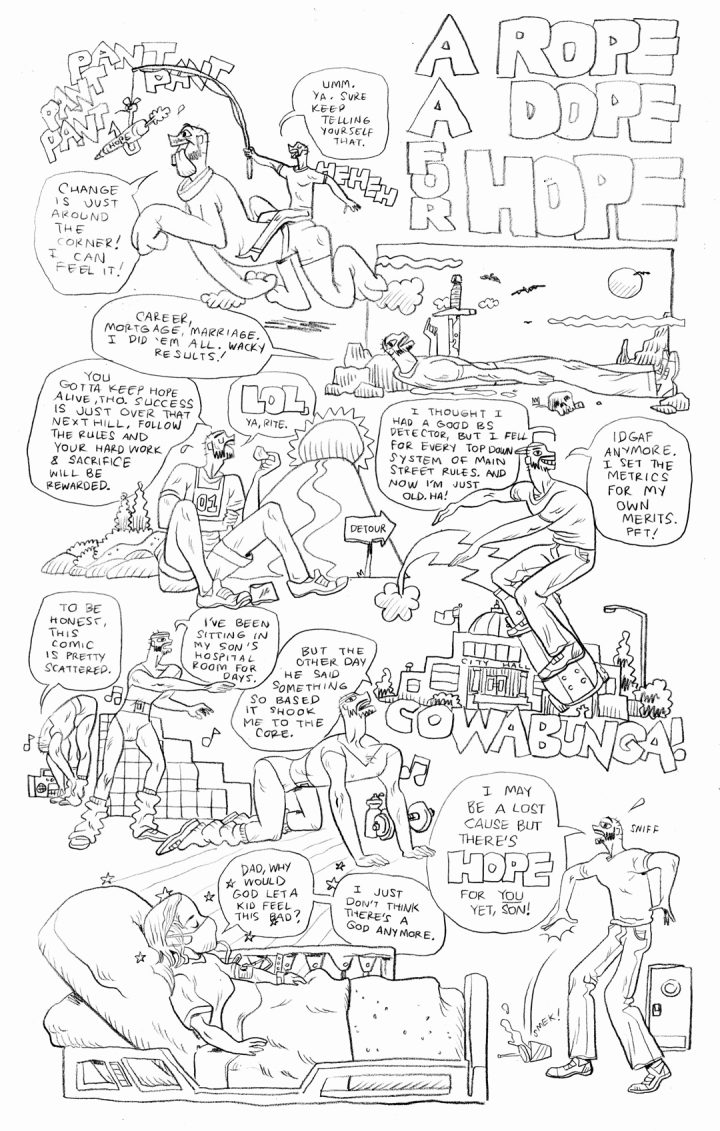

If it could be a one-man anthology, but that’s not a traditional graphic novel, is it? These almost-one-a-day pages I’ve been doing — you’ve been reading the stuff that I’ve been just taking photographs of on my phone and posting to social media?

Yeah.

I could do that as a graphic novel.

How about one contained story?

I could do it if it was autobiographical, and I never thought I’d hear myself say that. It has been effortless. I’m just writing down what happened and trying to be witty. I could do that. I’d never thought I’d say that, but I could do that. I’ve got about 50 pages of the next Cartoonshow which would be a bunch of weird stuff that I like to do in a weird world.

That would be issue 3.

Yeah.

The first two issues were published by Drippy Bone Books. How did you and Keenan Marshall Keller connect?

Probably on the internet, in the days of Myspace. We have a mutual friend. Keenan’s from Florida and he put out a record by a guy I used to hang out with in my hometown who was in a bunch of bands. Some of the trashiest people I’ve ever met in my life, but they make good music. Keenan put out maybe one or two of his records — Gary Wrong.

You seem to have quite a collection of stories about getting yourself in strange situations. I want to throw some words and names at you to find out the truth.

OK. [Laughs.]

Birdemic. You were making a comic based on the movie?

All right. I screwed that up because when it was time to do it, suddenly my partner wasn’t there. That’s when the marriage started to go south. I laid it out and thumbnailed every page. Jason [Leivian] from Floating World wrote the script. I’d been trying to get the rights to do Class of Nuke ’Em High from Troma. I’d been talking to Lloyd Kaufman and he was talking to me via email, but he got busy with something else. Then I talked to somebody who was like, “I know the guy who directed Street Trash.” We ended up talking to him and it turns out that the star of Street Trash [Mike Lackey] wrote Spider-Man comics in the ’90s. They were going to put together Street Trash comics and he was like, “I already promised him, but I know this other guy who just produced Birdemic 2.”

This is quite the B-movie odyssey.

Right. We talked to him and he was in Austin, Texas. He said, “OK, we can do it, but it has to be an official comic book adaptation of Birdemic 2, not 1. I only have the rights to part 2.” I did a lot of the work there.

This is all your doing? No one came to you for this. You were trying to obtain a property?

Yeah, yeah.

Why? [Laughs.] What was your end game? Just to make a comic out of a movie that you enjoyed?

Yeah, but I also thought — I was naive. I thought, “Maybe this could be a paycheck.” [Laughs.] It was around the time Tom Scioli got the rights to Transformers and G.I. Joe.

There’s no way he got the rights to those. He was making work-made-for-hire.

Right, right, sorry. I was like, “How is he doing that?” I thought that I definitely wasn’t a Transformers or G.I. Joe guy but I could probably do a Troma comic.

And you got Jason involved?

Yeah, yeah.

How many pages was this going to be?

32 pages.

Where is it now?

It’s in my studio in a drawer. [Laughs.] It’s mostly done. Jason made it really good. He did a really good job. He’s smart and it’s funny, but it’s not overtly funny. There’s a flamingo attack at a modeling shoot.

Second story I’d like to know more about: How did you get involved with Shia LaBeouf?

Oh, man. This one I still don’t understand.

All I know is that you were tangentially involved with him somehow for some amount of time.

He wrote a minicomic that was like three short stories and one of them was a poem. This was right at the time where everybody was like, “Whoa, he’s making interesting zines.”

I was at Wizard World Chicago and he showed up unannounced and sold his two printed zines there for a few hours.

At the beginning, that was cool. If he would have been legit doing that, but it was so disappointing. It turned out he plagiarized Clowes — everyone knows that one. I drew his minicomic he wrote and he asked me, “What’s your rate?” Back then I didn’t know. I said, “$300 a page?” He was like, “Done.” His mom mailed me a check. [Laughter.]

How did he get a hold of you?

He DM’d me on Twitter.

There is a comic completely finished.

It is made.

What is it called?

It doesn’t have a name. There’s three different little stories in it. They are kind of like poetry, almost like John Porcellino. Everything weird started happening. It got weirder and weirder. Do you remember all this shit? He did the Clowes thing and then he was at Cannes and wearing a brown paper bag on his head.

The “Please Forgive Me Tour” or whatever.

Yeah! I was sending him messages like, “Are you OK?” We were texting. And then Renee French emailed me and wrote, “I just wanted to warn you that we had invited him to contribute to a zine and I Googled it and all the text in his story is plagiarized.” I have a friend who is a high school teacher and I sent him the scripts that I drew and said, “Use your software and see if this is plagiarized.” Get this, RJ — one of the stories I drew was from something like Details magazine in 1999 or 2000. It was a poetry contest that somebody won and got published there. That’s one of them. The other story I drew was from an actor’s textbook for somebody that is taking a theater course. Those have little scripts in them for you to act out in class. One of them was one of those. I can’t remember the third story I drew, but it was weird like that too. I was thinking about it and it was like, “This is just stuff he had laying around his apartment.”

Did it get printed?

No copies were made. It kept getting worse and worse and then he tweeted a time and place. He was texting me things that seemed suicidal. I got in touch with his handler and those texts, he wasn’t suicidal, but that's when he was skywriting over Los Angeles. I thought he was going to commit suicide. Communicating with him was very strange. Then, right around that time, I got asked by Pen Ward to do Adventure Time. I emailed Shia and said, “I apologize. I’ll refund all the money. But I have to take this opportunity.” He said, “I understand. Keep the money.”

Hey!

Right? [Laughter.] I don’t know, man. He did terrible things during that time and it was wrong —

He’s done much worse things after that.

I know, I know. I keep thinking about making some comics about my interactions with him, but then — I drew a picture of him and put it on my Instagram a while ago and a friend of mine told me he was an abuser and sent me some articles. I don’t want anything to do with that shit. But that whole thing was very weird. Then Pen emailed me and asked if I wanted to work in Adventure Time.

That's a good segue. It was a straight-up email from Pen Ward.

I was at TCAF selling Cartoonshow #2. A guy comes up and buys an issue and I said, “Can I sign it and draw something in it for you?” I said, “What’s your name?” and he said, “My name’s Pen.” I go, “That’d be a great name for a cartoonist,” and he said, “I am a cartoonist.” I looked at him again and recognized him. I asked, “Can I take a picture with you and send it to my kids?” When I got home, he emailed me with another woman who used to work on Samurai Jack who was the show runner or something. It blew my mind. I knew nothing about animation.

I was going to ask what your experience in animation had been.

Nothing.

What was your first job there? Did they have you jump right in?

Right into storyboarding and character design. Right into it. They said, “Hey, just look at this ‘Storyboarding the Simpsons’ Way’ PDF.” [Laughter.] I was so nervous, but it was so rewarding. We start off with the writers — there was a team of four writers: Pen Ward, Adam Muto, Jack Pendarvis, and Kent Osborne, that also works on Spongebob. They’d give me like a five-sentence prompt. “This stuff has to happen then you can do whatever you want.” All of those weird worlds that I build and then end — it turns out that that works really well when you’re doing episodic storyboarding on a cartoon.

How many episodes did you have a hand in writing and storyboarding?

Two. Just two. Then I did several title cards.

How did you find working in animation different from making comics?

First of all, I was getting paid so well that nobody could tell me that they couldn’t watch the kids. And even if they did, I could hire a babysitter. I’m telling you, that’s the biggest thing. That’s why I could finish a TV show. I’m not an expert on it, but I’ve storyboarded enough now to know that storyboarding is on the same spectrum as comics. The difference is that in a comic, on one panel a person can be throwing a baseball and in the next panel there can be a broken window. You intuit what happens in the gutters. In storyboarding, you need to draw a fucking schematic of the baseball going through the air and where the the glass is breaking. Whenever I draw a character running all over a world not saying anything like in my comics, that’s the kind of shit you’ve got to do when you’re storyboarding.

Adventure Time transitioned to The Midnight Gospel for you. Were the same people working on that show?

Yeah, so when I was dating an ex-girlfriend and going back and forth to Los Angeles to visit her, I started asking around. I got frozen yogurt with Pete Toms and Aleks Sennwald. She was still on Adventure Time. I told them I’d like to get back into animation. I also did a book signing for a minicomic called Choreograph. There were just about three panels on each page and I did that because I wanted to do something that I could finish. I was going through a very difficult time and I was learning all this stuff about my ex-wife and the divorce was getting very bad. I gave myself a formula and I said, “Every morning I’ll do one close-up, two to three sound effects, one set-up shot, and one action shot.”

Other than your most recent autobiographical pages, I think Choreograph is by far your best work. I think it’s great. Those last transitional panels on each page where the man is floating, or diving, or falling — I find those really powerful. I figured the whole book was about transition, both forced and willingly.

The guy has a bag over his head and he’s running into surprises left and right. That was a time where I was like, “Wow, so there was another bank account. Oh, so there was an affair.”

You can feel that in the book even though there’s no text.

I only printed like 50 copies of it.

I have number 16 out of 50 sitting right here in front of me.

I would love to do more of that, but I just don’t know if anybody — anyway, it warms my heart that you liked it. But that panel at the end of the strip, I added that and it just felt like music. I printed 50 of those and I did a book signing at Secret Headquarters because, at that time, I thought, “Why not?” Victor Cayro was there. [Laughs.] It was a good time. I think that put me back on the radar of Pen. I got an email from a producer at Titmouse and he said that Pen wanted me to ask if you’d test for this show for character design. I tested and then they were like, “How about storyboarding instead?” I did two episodes of that show. There are only eight episodes, but I did two. On those I felt like I got to do a lot of heavy lifting and got a lot of freedom. Especially episode three with Damien Echols. Are you familiar with him?

I’m very familiar, yeah.

That was an honor to do that and I took it as such. There’s a lot of stuff going on in that episode where he’s talking and there are all these cats. Everything that is in the frame and in the scene that is happening, I did my best to make it reflect back on his words and everything that he is saying. I’m really proud of that. On no level have I experienced the injustice that he did, but on a little, tiny spoonful I’ve got some that I’ve had to deal with in the past.

There’s the Southern connection as well.

Yeah, yeah.

Are you planning on working more in animation in the future?

Yes. I’m going to learn how to use a tablet. Everything I’ve done has just been pencil and paper so far.

From reading your comics for a long time and considering your style, the fact that you’ve done everything in pencil and paper seems insane to me. Are you using a lightbox?

Yeah, I have a flat LED Monoprice that Ben [Marra] told me about years ago. I do this thing that I call “Two and I’m Through.” I was drawing with Ed Piskor years ago and I said, “I got this new thing I’m doing. It’s called ‘One and I’m Done.’” I would draw it and then transfer it onto the final and I’d just do pencil. He’s like, “Derek, that’s two. That’s ‘Two and I’m Through,’ homie.” [Laughter.] The daily stuff I’ve been using a grainy pencil on lately, that’s just on copier paper.

That style you’re using currently feels more immediate.

It needed to have that feeling for what it is. I can’t exactly say why, but to be a diaristic memoir I needed it to have that feeling.

Was this style shift made consciously or just came naturally because you were trying to get everything down on paper so quickly?

At first I was doing things like “Screwed the Plug,” which I’m going to do the last one. I just haven’t done it yet because it’s like — I got kind of emotional about it, so... I know what I’m doing for that, but I was just taking photos of it every day. I drew a page where I refined that and made it look like the other Cartoonshow or Choreograph pages where I pencil on plastic, a translucent plastic. It looked too refined, RJ.

Wait, you pencil on plastic?

Yeah, it’s just this stuff called Yupo. It’s this translucent plastic that some people use to get weird watercolor effects. Years ago I made the decision to quit inking because having markers and ink around little kids — it never ended well. [Laughter.] I was like, “This always ends up being a mess and I don’t have time.”

When you pencil on the plastic, how do you get — I guess I just don’t understand the process.

Another reason I quit inking — have you ever been in a band?

Not really. Nothing serious.

I was in punk bands. This is what inking was like for me: You go to a venue and play the best show you’ve ever played. It’s great! That’s pencilling. Inking is coming back the next night and recreating the entire experience. My pencils are that tight so I looked into this plastic. I know Jae Lee, the mainstream comics guy, just does pencils and I know that Tom Scioli was doing just pencils when he did the Transformers stuff. I liked how that looked. I tried drawing on translucent tracing paper, on vellum, and it wasn’t tight enough for me. I found this Yupo that’s polypropylene and paper-thin. I’ll put it on the little light pad and underneath it I’ll have like a quarter-inch thick sheet of white shelf liner that I get at Walmart. That allows me a little push and pull and I have some give underneath. I just go hard with pencils on it. As hard as I can. I use a 2B and a 4B pencil.

Do the pencils have to be duller to not puncture the plastic?

The good thing about this is that you can’t tear it nor puncture it. There are two different 2B pencils that I use — I have a super-sharp one and then I have a dull one. It gives me different line densities. But on the daily stuff, I just use one pencil.

Do you use a lot of drafting tools?

No.

I ask because your work relies on these impossible angles. How do you achieve those lines?

I mean, I’ll use a ruler sometimes. For a big curve, I have three French curves.

For some reason I pictured your workstation full of every drafting tool around.

I used to want that. I would buy them, then they would just sit there. I use a ruler, but that’s about it.

I’ve got a question about your style, but I need to find a way to articulate it. If you’re going to draw something like a car or a woman’s leg, do you first process what that might look like photo-realistically in your head and then add your unique geometry to it? Or does your brain work in a way where images are processed immediately in your style? Does that make sense?

Yes, it does. When I am drawing nowadays, because I’ve just practiced so much, it’s kind of an exciting thing to get a rough piece of paper and, as I’m going, try to make the fastest and most interesting decisions I can. A lot of it is just about what feels good to me. I’ll do it on a rough piece of paper first and then, if I like it — you ever look at popcorn on a ceiling?

Yeah.

Or like wood grain. You see stuff in it. If I’m sitting in the yard with my kids, I’ll fill papers with shapes. Then I’ll go inside, look at those shapes, and go, “Is this a leg? Is this an arm? Is this a building?”

What comes out of that?

I put them in the comics. I try not to do too many steps now. But I don’t do any of this with the daily stuff now. That stuff I’m really making up as I go. That fucking car I drew yesterday, I just made it up. That car does not exist in reality.

To do everything you just explained, it’s obvious to me that you have a ton of confidence in your abilities.

Thank you, and yes. You’ve got to have that in life, right?

I guess. That’s easy to say, but —

Yeah. You can’t fake it. You can’t fake it. It’s a combination of confidence and I just don’t care anymore. It doesn’t matter. I’ve failed as many times as possible and now I’m not sweating failure. I’m going to continue to draw this stuff and I don’t care what comes out of it. It would be cool to make a book out of it, but I’m going to do it either way. There's confidence in that. But also being a dad and doing everything else — that shit is hard. That’s the hardest thing.

You wrote once in a comic, “Hope and fear are the same thing.” Could you elaborate on what that means? Do you believe that?

I believe that. That page and sequence is going to be about that idea. Ooof... See, this is something I'm still trying to work out. I feel like they are different sides of the same coin. This is going to put me in a vulnerable position, but being married, the marriage ending, or the marriage doing well — however it was at certain times and trying to maintain a family — I found a lot of times when I look back on that where I was hopeful I also felt a fear. Was it hope or was it fear?

Fear of what?

Losing my wife. Losing my family. Then I started thinking about other times in my life where I thought, “I hope this works. I really hope this works.” Just listen to that.

There’s the hope.

But it’s fear! I’m just trying to be positive. I’m afraid and trying to put a positive spin on it. Does that make sense to you?

It does now. When I read that line, it didn’t make sense to me, but what you just said right now made it clear.

Yeah. RJ, I feel like I put up with a lot and stayed in a marriage for two decades because I was hopeful. I had hope about the way things could be. But really I was saying to myself, “I hope it works. I hope it’s going to be good now.” I was just afraid of losing everything. I’m still working out how to word that better, but it’s a feeling I have in my heart definitely. Hope and fear feel like the same thing, but opposite temperatures.

Now it’s my turn to be vulnerable here. Do you ever feel you’re a fucking failure as a parent like all the time? Because I do.

All. The. Time. My kid is in here suffering, crying, and I’m doing everything that I can do that’s possible. Everything. But it doesn’t matter and it’s not helping. The other day, my daughter did a bunch of really nice stuff to help me out around the house and then asked if her boyfriend could come over. I snapped at her. I saw her eyes get glassy and she went to her room. I was like, “Oh, fuck. She did the dishes and made dinner. What am I doing?” I even like her boyfriend and he’s nice. I had to go in there and be like, “Hey, I’m sorry.” Constantly. Constantly. If you can get close enough with them and make them feel comfortable enough to where they can tell you anything and talk out anything, then when you fuck up, you can just be like, “I really fucked up just then. Can we be cool now?” Then you can talk about it.

That’s good to know. On the flip side of that is if you feel like you’re fucking up as a parent you’re at least caring about how you’re doing.

Let me tell you, just as much as I think I fuck up all the time, when I go to a PTA meeting I think I’m better than everyone there. [Laughter.] I roll my eyes all the time. You should see me now at these types of things. You should see me enrolling my kids at school. “Where’s the principal? Tell him to get out here now. My taxes pay his wages.” [Casey laughs.] I’m not nice now. I should be and sometimes I’ll have to apologize to teachers and administrators.

With the exception of the comics you’ve made over the last year and maybe not even a handful of other cartoonists, why are parenting comics so awful?

You know, I want to say something. [Laughs.] “There’s room for those pastel parenting comics too,” you know? Vanessa Davis replied to me recently and said most parents can’t afford to make comics. That’s something that’s got me fired up right now. My point of view and the things that I’m going through, a lot of parents in America have to go through too. They just don’t have the time or don’t get to make a movie or write a comic about it. But it mostly comes down to not having the fucking time to do anything. There’s probably been hundreds of really good parents that could have made great comics that we’ll never see. But the people now — man, I don’t know what background you come from. What did your dad do?

My dad was a public elementary school principal.

OK, then you know. All of these people who do parenting comics for something like New York Times Parenting — what kind of people do you think they are? I’m not going to be mean to them, but what kind of folks do you think they are? They are in a different economic place then we are. Every now and then you’ll get somebody doing a parenting comic about being a single mom. Lauren Weinstein just did a comic, which was good.

Yeah, that was good.

Really good. I’m not knocking that comic at all, but in my mind I’m like, “I wish any of these women featured in the comic could have been able to have their own voice and do this comic themselves.” But I’m thankful Lauren could do it.

You’ve written briefly several times in the past about Lynn Johnston.

Oh, yeah!

Is she an influence of yours?

At this point, my biggest influence. The cartoonists I’ve been really into over the last few years have been Wilfred Limonious from Jamaica and Dan DeCarlo, but when I was starting to do these little comics about parenting I started thinking, “What am I overlooking?” Years ago, Tom Spurgeon would talk about For Better or For Worse. He’s the only person I’ve ever heard talk about it. I respected him immensely, so I thought, “If Tom Spurgeon talked about that strip, maybe I should research it.” I went to the library and I read a biography thing about her and I’m looking at all of her comics and she’s being honest about things. Like, she’s being honest about things in her comics in the ’70s. I didn’t know that her husband left her. She had a toddler and then her husband got her to move to the other side of Canada away from her family. He had a mistress and then got on a motorcycle one day and said something like, “You can keep the kid and the house. I’m out of here.” Then she started drawing comics more seriously. Of course, reading that, I’m like, “OK. All right.” [Laughter.] That’s when I decided to sit down and pay more attention to her comics. She’s saying stuff like — in one strip she’s comforting her kid who’s whining and crying. At the end the kid is like, “I love you, Mom. You’re the best mom ever.” She’s carrying the kid to bed and has a thought balloon that says, “Wow, it’s crazy that this morning I wanted to give you away.” [Laughter.] I haven’t seen honesty like that very much. I love it. I’m way different, but it’s inspiring.

Speaking of influences, you’ve been at this long enough now that you’ve undoubtedly been an influence on some younger cartoonists. I can kind of think of a few off the top of my head too. How does that feel for you?

Is that true?

It’s true. It’s got to be true.

I don’t know. [Laughs.] If it is, that’s flattering. I feel like I’m just getting started, you know?

That’s a good feeling to have, I think.

It is. One day I’ll have a book. I’ll do that. [Casey laughs.] Yeah.

You’ve brought that up a couple times already. Is publishing a book some hurdle you feel like you absolutely need to cross?

Yeah, and I think I’m finally ready. I could do it now and I want to do it. That’s what I really want to do next. It could be short, it could be long, whatever — I’ve got to check that off the list.

What else is on that list?

You know, five years ago, I made a five-year plan of goals. I accomplished them. Now I’m starting to think of a new five-year plan and I think on the list is that I’d like to make a book with a spine. As long as it has a spine. [Laughs.] I want to teach more. I want to work in TV some more, but it doesn’t have to be all the time. I’d like to make more minicomics. It’s a realistic plan. But a book with a spine, that’s something I've been trying to do for a long time.

I have to assume publishers have shown interest in you in the past. Have you ever been approached to do a book or pitch a project?

I would say that you should not assume that. I don’t know why, but no.

Was there a shift in the way you thought about your art when you became so prolific over the last year or so?

With the memoir stuff I felt like immediacy was key and it needed to look immediate. When I’ve gone in and tried to make it more refined, I didn’t like it. I realized the first pass — leaving things almost as thumbs — hit the tone. I could just kick those out so fast, you know?

In the past, your coloring and lettering have been some of your definite strengths. Do you feel like your newer work is missing that in any way?

I’m putting lettering in it, but it’s different. I’m not using a ruler and I’m not getting fancy with it because I want it to almost feel like a newspaper comic. I am not going to stop doing the other stuff where I do the graphic coloring and tighter lettering. This isn’t a replacement. I’m not stopping, but I did that for the past year and I’m sitting on a stack of those pages. Now I want to do this for a while. I’m not going to stop working in my original style though.

Were you nervous about all these intensely intimate autobio comics going out there? Some of them have been very sad. Some of them have been shocking. That one page — “People Who Have Pulled Guns on Me from Memory” — was eye-opening for me. There’s 11 people!

We need to talk about this. I imagine that’s happened to you, but it sounds like it hasn’t.

I've never had anyone pull a gun on me. I’ve been around guns before, but they’ve never been a surprise.

OK, OK. We have to talk about this stuff. The way everything is changing, we have to talk about it. I want other people in other countries to know.

Know what?

How America really is. I’m not trying to get political, but —

Everything is political. Surviving in America is a political act.

A lot of things that I’ve found especially during COVID and then trying to get any type of aid as a single parent — RJ, that stuff has been defunded so much since the ’90s it exists in name only. It’s absurd. We've got to talk about it. We’ve got to. I can’t just walk around talking to strangers about it.

And that’s why you’re making these comics.

Yes! Like, the temporary emergency family assistance that you think — there’s no welfare, first of all. At least here in Florida and in Alabama. There’s none. You think there’s the temporary emergency family assistance. No. You can get in touch with somebody who can maybe go after the parent that’s not paying child support’s paychecks. But what if they don’t have paychecks? I applied for all kinds of stuff. We lost everything and are still struggling. But if I wanted to get rent relief, I’m not eligible. On the site it says, “How far behind are you?” Well, I’m not behind. I’ve worked my ass off and now I’m trying to plan ahead because I don’t know how I’m going to do the next little bit of time. Then you’re not eligible. If you’ve been primarily the homemaker and a parent and suddenly the partner who was the breadwinner is gone, if you don’t have savings or something then there’s nothing there for you. Your labor had no financial value. I can’t show it on paper that I potentially lost money, so that’s why I did not get any COVID relief. We’ve got to talk about this stuff. I can’t be alone in this and I don’t think I am.

Definitely not.

It seems now that if I just get on Twitter or something and make jokes, I’m lying. But I don’t want to make a World War 3 Illustrated political comic. Those are fine, but to me, I’m making family comics. These are modern American family comics.

Were you apprehensive about being so honest? The “Screwed the Plug” series, for example. There are nine episodes of that saga currently.

Yeah, that’s why I haven’t done the last one yet. I’m worried about people involved reading it, but I don’t think that they are. I’m worried that people are going to think that I think I’m some sort of tough guy. I’m not. I just lost it. I don’t want people to think that I’m like, “I’m a badass,” because I’m not. I’m a dumbass. That’s what I’m really trying to get across. [Casey laughs.] I did a lot of dumb stuff. I was losing my mind.

Have your kids read any of this stuff?

My daughter. She absolutely loves it. I asked her if it was OK if I wrote about it. And I’ve left stuff out of it to make it not as bad. I have other stories to go along with “Screwed the Plug.” That’s just one story, but I’ve got more. To me, it all exists in my mind as one book. That’s how it exists in my mind. While all the stuff was happening, I was trying to make Cartoonshow #3, so in my mind — I was talking to Zack Soto about it. He was like, “Yeah, you want to feel like you're making 8 1/2.” You know Fellini? I was like, “Shit, that’s a good point.” In my mind, I’d love for it to fit together like that. Like, “Here’s where I had to deal with this, drawn in a scribbly way, but I got home and drew this alien landscape in a colorful way.” I don’t know if I can do that. In my mind it exists as the same body of work.

That would be interesting. You said you have one more “Screwed the Plug” episode. Where do you go after that?

There’s two more stories I want to tell that are equally sad and funny like that one.

Is that a tough balance to maintain?

Yeah.

I can tell you this — it’s a tough balance for the reader.

I have to push myself to go there. There have been times where I tried to do stuff that was just funny and I end up thinking that it's just OK. I have no desire to do just sad stuff either. That’s how I’ve gotten through every challenging situation in my life. When you recover and get your breath back, you can stand up and joke about it. At least you’ve got that, right? [Laughs.] Maybe that’s just me.

Do you feel like you're working at a higher level right now than you’ve ever had before?

This is the best I’ve ever been in my life.

I think that shows.

Wow. Thank you. I’ve just figured out a good balance with home and the kids. But, you know, when a kid gets sick like yesterday, things slow down a little bit. We also got past some really difficult times around here and some people who were bothering the family have left town. I think that’s permanent. But I have no plans on stopping. I’m not stopping. I’m just getting started.