Many things describe a book by Beatrice Alemagna but words alone have rarely done her work justice. Based in Paris since 1996, Italian-born Alemagna has published fortysomething volumes and received numerous awards from multiple countries. Among these are Italy's Premio Andersen, the New York Times Best Illustrated and New York City Library's Best Children's Book, Germany's Huckeback Prize, the English Association Book Award, the American Society of Illustrators' Gold Medal and, in France, the Grand Prix de L'Illustration and the Prix Landerneau.

She's also been nominated for the Hans Christian Andersen Award, the "Little Nobel of Literature" as well as – four times – for the Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award. In 2013, she was Guest Honouree at Italy's Lucca Comics Festival.

Yet every volume Alemagna produces is different. Handwritten on a scrap stuck to the wall of her studio are the worlds "IL ME SEMBLE QU'IL N'Y A PAS D'INVENTION SANS RUPTURE" ("Without disruption there is no creation"). For every project, she tries to wipe the slate clean. "My studio is a place I go to become something larger," she told fellow illustrator Delphine Perret, "to surprise myself and break what might otherwise solidify into mental stereotypes… I have a terror of repetition." There is, she says, no ritual to how she works. But there's always a rule: don't repeat yourself.

Only technically does Alemagna make "children's books". Each of her volumes is a new installment in an oeuvre that varies as much as her materials, which range from paint and pastel to crayon and collage. They might create colors and surfaces that recall Edouard Vuillard or Paul Serusier. But, equally, Alemagna might choose to just balance flat tints and simple shapes. She is an inventive colorist who favors strong and intense contrasts and she has a very visceral sense of texture. But what compels the eye about her work is something greater than style. It's her thorough integration of rhythm, feeling and design.

Alemagna was born in Bologna, Italy. Her mother, a psychologist, and her father, an architect, always encouraged their two daughters to draw. Early on, Alemagna determined what she wanted to do. A seven-year-old Balzac, she decided to become "une peintre des romans", a "painter of novels".

Over several years, she studied graphic design at Italy's ISIA Urbino, the Istituto Superiore per le Industrie Artistiche. But she was also teaching herself illustration – and she found inspiration in children's books from France. Many of the French albums she admired combined excellence and adventure – just like her favorites by Tomi Ungerer, Astrid Lindgren and Gianni Rodari. So in 1996, Alemagna entered the illustration competition of Montreuil's Salon du Livre de la presse jeunesse. When her entry took first prize, she moved to Paris. For a decade, she paid her rent designing posters for the Centre Pompidou.

Although Alemagna insists on change and forward motion, nothing she does is created hastily. She thinks of herself primarily "as a narrator … Words are as much my tool as a pencil or a brush. If I don't get the words exactly like I want them, I can't see the image. So everything is born from the text."

For every project, she does intense, exhaustive research – filling her sketchbooks with observations and storyboards. "Before I start a final drawing, it has to be clear in my head. It has to be fully developed… I will have made sketches that I've redone dozens of times." If an image won't come out of her head and onto paper, she lets it go for a while. It may be abandoned for a few hours or for six months. "I can do it, but throwing myself at something never leads anywhere."

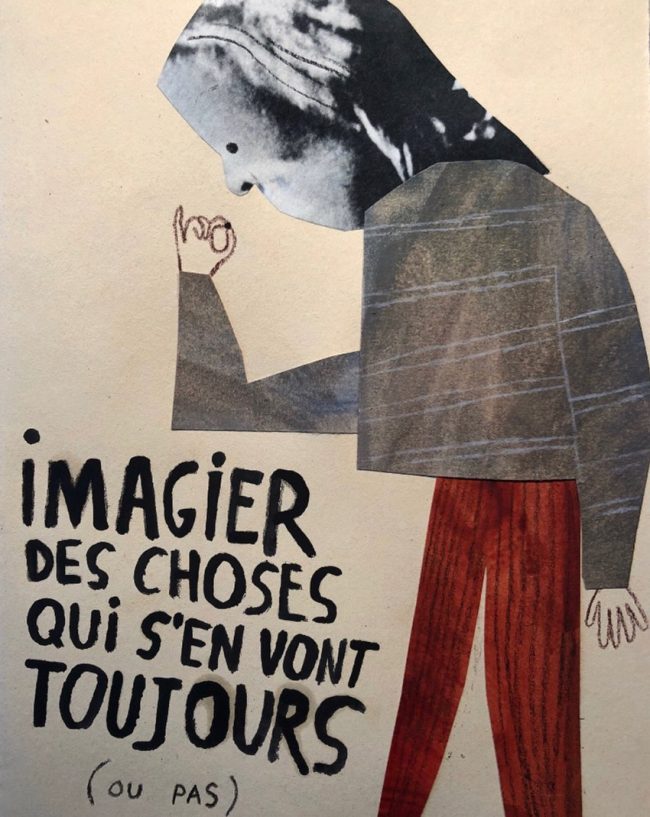

Alemagna's latest book, Forever, is a poem about the ephemeral. (Already available in six languages, its title in French is Les Choses qui s'en vont, "The Things That Go Away"). Every other page in it is a transparency, on which readers see something evanescent: falling hair, a bad mood, the curls of steam from a cup of tea. As you turn these, each covers a different page – transforming each two-page spread. Musical notes merge into the leaves of a plant; tears melt into the fur of a family cat; the ghost from a bad dream vanishes into wallpaper.

During our quarantine, the book has been much talked about. When Le Figaro asked one bookstore for reading recommendations, they put it on top. "All of us," said the respondent, "are trying to get our heads around two ideas, the idea of loss and that idea of what we'll find on the other side … in terms of that, Alemagna's book is both audacious and subtle."

The artist's workspace itself has appeared in books. One of these, last year's Les Ateliers by Delphine Perret and Éric Garault, is an elegant tome that considers creation. The other, Jake Green's The Bookmaker's Studio, is a photographic hymn to artists who make for children. In both, Alemagna's studio stands out for its lack of computer. "I never use one; everything is made with my hands."

This week, a few French quarantine restrictions were lifted. But, for the "red zone" that is Paris, only stores, churches and cemeteries re-opened. I asked Alemagna how she was faring.

Cynthia Rose: What has your world been like? Can you get to your studio?

Beatrice Alemagna: I live by the Canal Saint-Martin, where the neighborhood has just become more and more chic. When I moved in twenty years ago, that was hardly the case. I'm very lucky because, after having worked for years in my apartment, now my studio shares the same landing as my door. It means that, from the start of quarantine, I've been able to go there every day. Still, despite these dutiful pilgrimages, for the first two weeks I wasn't at all productive. I felt overwhelmed by the whole situation and just couldn't manage… I was totally demotivated.

It was a real lifesaver, though, that I could get away from this little Parisian apartment because here we're always on top of each other – my partner and our daughters, who are nine and four. Actually, because they love to stay at home, the girls have made no fuss about not going out. But since they're both fairly young, they do want to play. They want to take advantage of every moment to make things, dress up ... plant avocado pits along the windowsill.

Most creators are used to solitude. But, if you're no longer out in the world you're rendering ... when you're no longer among people and nature, that's different. How have you found it?

I find that it doesn't change my daily life too much, even if I no longer see my friends or go for a walk by the canal. For me, what has seemed most positive – in a situation that is nevertheless quite gloomy – is that for the first time I spend every day with my daughters. We are doing things together and, above all, I don't have to run around all over the place. So I think it's also been a time to catch one's breath. It's a moment to question ourselves about all those things making a noise inside us that we don't usually hear.

When the quarantine began, what was the state of your projects? Were plans or commissions cancelled or delayed?

When the quarantine started, I had no books due for release; more of my projects are due to come to fruition in 2021. Those projects which are still in discussion haven't been delayed or cancelled … except for a book in Italy, A Sbagliare le storie ("Getting Stories Wrong"), by the great auteur Gianni Rodari. That came out right in the midst of Italy's Covid whirlwind.

It was meant to be presented at the Bologna Children's Book Fair in March. It did come out anyway. But, conceivably, it might be re-presented at next year's fair since that's the occasion when Rodari's centenary will be celebrated. Obviously, of course, all my trips were cancelled. But as I said, for me it hasn't been too painful… outside of various economic circumstances.

For years, I've dreamt of the chance to rest a little, so I could give myself over to the whims of the moment. Now I'll admit that the idea of picking up the very same rhythms as before – that panics me and I find I'm really questioning it. Am I actually capable of doing that? Do I even really want to?

Without any doubt there's going to be a before and after. And I’m certain that, in addition to everything that will be felt politically, socially and economically, there will be concrete effects at the personal level. For everyone, it will affect things like our rapport with others and everyone's relationships to their work.

Have you had any logistical difficulties?

I did have one moment of enormous anxiety. Because, a week before everything was closed, I should have gone out and bought those sheets of paper I've been using…But, instead, I put the purchase off until after what I didn't know would be the last moment. By then, it was too late. So I was terrified that I wouldn't be able to work. But that passed once I found some sheets under my studio table…

They had been buried beneath all these boxes filled with drawings and books… and I just started drawing on this paper I wouldn’t have thought of using at a different time. This one small event helped me remember something I already knew: shat constraint is fertile and it's an activator of creativity.

Being prevented from something permits an artist to find something else – sometimes it's technical but it can also be emotional – that is truly creative. It's like a child who will use every scheme imaginable to reach a box of candy. It may be sitting somewhere high up, far out of reach. In the end, somehow, he'll always manage to get it.

Your work makes me suspect you are fairly disciplined. Have you noticed changes in how you're working?

I'm sorry to disappoint you, but I'm not at all disciplined! There's not the slightest order in my process or my technique.

All my tubes of color are totally brutalized. I crush them up without the smallest thought or respect – either for them or for all the brushes that get shoved together in pots… brushes that are totally grubby and bedraggled. I haven't got any consideration for tools… For instance, out of sheer stubbornness, I always break all my pencils and pastels.

For literally years now, my work table's had this carapace of filth… it's very tenacious and, probably, it's now also permanent. And no, that's not the stereotype of the crazily inspired artist or the creator lost in a mystical state.

It's just the effect of immense disorganization and a kind of mental mess that never ends… Which can sometimes be rather exhausting. So, really, nothing much has changed over the course of this particular period. It makes me think of this picture I'm going to send you: "The Artist", "The Solitary Artist", "The Artist in Quarantine" and "The Artist After Quarantine".

I want to ask about two series you've shared in the quarantine. One is a set of visualized couture brands – images tagged "Rykiel", "Hermes", "Miyake", etc. The other is a wide-ranging set of artists' portraits, which has included Keith Haring, Edvard Munch and Georgia O'Keefe... Are they part of specific projects or more of an experiment?

I'm making both of those as a form of personal exercise. It's a way to learn from myself; to force myself out of patterns and formulae. I know certain patterns are the 'mark' of any artist. But I also think they can become problematic.

But they're also … to keep myself entertained! I like to draw without a specific audience, without a given narration to support the drawing. It allows me to go where I usually don't with work when, for instance, I do something like a book.

Much of what passes for communication at the moment is pretty limited to "social" networks. How do you manage these; do they help you … or not?

I handle social media quite badly.

I'm often monopolized, fascinated, by others' lives.

Like any artist, I feed on information and the images that I find anywhere and everywhere. This sort of nourishment can help me, of course, but often it takes me too far from where I wanted to go. It doesn't stop you from wasting too much time – on the contrary.

Deep down, I'm very angry with this slavery to which I subject myself.

This is a moment of reflection for everybody, one in which how we act will determine how we live. In terms of work and creation, what do you think it changes for you?

I think that now we're all now seeking things that really make sense, things stripped free of their habitual trivialities. Over the past few weeks I've had no desire to buy anything. Even buying bread has become an effort (especially since, like everyone else, I've started to make it in my oven at home).

Since the dynamics between purchasing and production have eased… I hope those usual rhythms will be changed in a permanent way. I also wish wholeheartedly that, in the world of publishing, our overproduction of books can decrease… to make room for works that are more essential, truly necessary.

During this period, what was your most unexpected moment?

My 95-year-old neighbor, whom I always see at the window, was very keen to convey a creation she invented. She managed to fashion her anti-virus mask by making paper boats and then planting them all over her face. Of course it was funny. But, more than anything else, it was a reminder that art and creativity are sometimes where you least expect them…. as long as you're still able to really see the things around you.

****

- Beatrice Alemagna's Forever (Thames and Hudson) is out now. Two exhibitions of her personal art are in the works, one this year at Paris' Galerie Treize-dix and one in 2021, at the Villa Verbeelding in Hasselt, Belgium.

- For other work, news, etc, see www.beatricealemagna.com and @beatricealemagna ; Les Ateliers (Delphine Perrault and Éric Garault, Les Fourmis Rouges) is available here and The Bookmaker's Studio (Jake Green) from here. Her most recent book published in America is Child of Glass, published by Enchanted Lion.