Simon Moreton’s wonderfully spare and evocative comics have steadily mined his memories, his biography and the world around him for over a decade. From his self-published series Smoo, his longer works Plans We Made (Uncivilized), What Happened (Kilgore) and The Lie of the Land (Ley Lines series) to his current series Minor Leagues, (along with scores of smaller books and zines) Moreton is continually challenging his own ways of working and telling stories. His work has grown more visually broad in recent years, using varied ways of mark-making and composing to more deeply investigate the world and how it is understood and remembered.

Simon Moreton’s wonderfully spare and evocative comics have steadily mined his memories, his biography and the world around him for over a decade. From his self-published series Smoo, his longer works Plans We Made (Uncivilized), What Happened (Kilgore) and The Lie of the Land (Ley Lines series) to his current series Minor Leagues, (along with scores of smaller books and zines) Moreton is continually challenging his own ways of working and telling stories. His work has grown more visually broad in recent years, using varied ways of mark-making and composing to more deeply investigate the world and how it is understood and remembered.

His latest book, WHERE?, recently published by Little Toller Books, continues that evolution, knitting drawings with texts and found materials to further dig up and interrogate his ideas and memories. I was glad to talk to him about the book and his work overall.

Warren Craghead: Let’s start with your new book WHERE? How would you describe it?

Simon Moreton: WHERE? is a memoir of sorts. It combines three strands - one about the events leading up to and after my dad’s death in 2017; one about my childhood in rural Shropshire, a county on the English side of the Welsh border (specifically a hill called Titterstone Clee - where my Dad worked on a radar station - and the village of Caynham nearby where we lived); and one about what happened when I tried to process my grief by revisiting that place and that period in my life. The story is told in prose, drawings, photos, pictures of things found in archives, and also sequential art - I’d be happy to call them comics though they’re probably at the slightly unusual end of that spectrum. The idea is that the book hands off from prose to comics and back to prose to tell different aspects of the story. WHERE? is about 350 odd pages long, and 50/50 prose and visual material, I think.

I really reacted strongly to how you used all sorts of visual documentation and storytelling to build WHERE? and tell this story in a powerful way. There’s a deep exploration of how to make a document about those things that is amazing in your book.

Mixing words and pictures was really important to me. I’ve spent a decade and a bit making comics, so whatever I was going to produce was going to involve pictures. At the same time, since starting my zine Minor Leagues in 2016, I’ve been experimenting with prose, and what happens when you mix that with comics. With WHERE? I wanted to carry on with that experiment, in which sometimes words seemed to be the best descriptive tool, and sometimes images - the chaos of being drunk on a roof, the glee of a child exploring some woods, or the feeling of being blown around by the gales on an exposed hill can be shared in pictures in a way that words can be too specific for. So exploring how to fold those elements together was the key challenge.

"Fold" is a good way of describing what you do here, folding all sorts of things in to unfold and expand the strands you are drawing and writing about. Your work has always used autobiography but with a wide scope that gives it a vitality and strength and truth. The slippage of memory is acknowledged and folded(!) into the work. Also questioning who you are, who your Dad was, how where you were affected both of those.

I really wanted the book to be more than just an account of things that had happened to me. I wanted to pay attention to *how* I was constructing that account, too. That’s because whether writing about my family’s experience of Dad’s terminal illness - he died six weeks after finding out he had cancer, which had been largely asymptomatic prior to his diagnosis - or writing about where I’m from and the people who lived there, I had to try and think about the wider context of whose stories I was telling. So I ended up trying to unpack my relationship with where I was from, and with my family, with my Dad, as an extension of a process of accounting for myself, and understanding all the other currents that created my context, and how that context created me. That meant accepting and admitting to the fallibility of memory - like the way that those of us lucky enough to have had stable childhoods can tend to rose-tint our experiences - to think about how the landscapes we grow up in affect us, our sense of belonging, and sometimes cause us to lay claim to places and times as if they were ours and nobody else’s. That’s why there’s lots of local folklore, historical figures and events, old newspaper reports, and more, folded into the story - to recognize other knowledges and approaches to life and death and so on.

That wider context became a vehicle for understanding other things; for example, there’s an underlying critique of masculinity, though perhaps it’s not super explicit. I didn’t grow up with a strong sense of ‘masculine’ roles or behaviors, because that’s just not who my parents were. But of course, I did encounter those things through other people - kids at school and so on. There’s also a class component, too - although we weren’t very well-off, we were in comparison to many of the kids in the area and that shaped the behaviors I witnessed and experienced, and how I experienced those things shaped how, as a child, I retreated into the natural world. That plays out in the subdued stories of the working class residents of Titterstone Clee hill, or in the predetermined paths followed by the wealthy men who crop up in the book, or how those people ended up dead or ruined or failed on account of their sexuality, or their want of ‘manly’ characteristics or whatever, while yet still being the holders of an immense privilege.

But that’s all in there if you want to find it. The book’s overriding purpose is to talk about death and life and what happens after someone is gone, and how that experience is so very life-changing; I think that’s the big bit and the bit that is perhaps most universal. I loved my Dad very dearly and had a great relationship with him. His death left a huge hole in my life, but like a hole in a spiders’ web, the monumentality of mending that hole becomes only apparent after you see the complexity of the structure that’s been broken. So you don’t mend the hole - you just make peace with it.

You are hitting on one piece of what makes the book so powerful - you embed your story in wider ones about where you were, both the social and natural worlds. It feels less like a camera on you and more like living, or remembering.

The British landscape has been relentlessly dug over, cleared, grown on, separated, built on, forgotten, rediscovered and so on. We have very little of what you could call real wilderness. So the natural idyll is a myth - it’s a human-made environment. But the pastoral imagination in this country has historically been very strong, with the rural folk seen as extensions of the natural world and thus part of its natural order, while the wealthy, the landowners, as being the stewards - and thus dominators - of those worlds. But that said, although the rural idyll is a political construct, it also has a kind of truth to it: growing up amongst nature has had a huge effect on me - who I am, how I see the world, the things I value - but that’s a complicated position to occupy. I’m not a son of the soil, but I am inherently bound to it in a way that feels almost animistic. For example, there’s a big passage in the book called A Shropshire Lad which in particular explores rural arcadias - it’s a sort of a semi-fictionalized ‘day in the life’ of me out and about in the countryside, climbing trees, playing on hay bales, encountering a woodland spirit, all that sort of thing. It’s both real and allegorical.

It reminds me of the suburban landscape I grew up in - fake but also real because people live there and have lives. We inscribe meaning to whatever circumstance we are in.

That’s definitely an extension of this, for sure. I think suburbs, insofar as they are a relatively recent development, had all sorts of ‘readymade’ culture associated with them - driveways for the car, white goods for the housewife, lawns for the mowing - that still exist in the cultural memory as ‘fake’. But as you say, when you inherit those places by living in or around them, you quickly realize they may be fake, but they’re also real. They get meaning and shape and purpose from you being in them.

For the rural landscape in England, that process of ‘invention’ has been going on forever. You see big phases of that emerging from feudalism in the 11th century, moving into the enclosures, where common land was essentially made private, from the 17th century onwards; then the landed gentry and the new industrial and colonial money continue to sculpt the countryside, literally moving villages to improve the view from their lawns; then there’s the ‘opening up’ of the countryside with cars and railways and another reinvention of what it means to be ‘rural’; then the mechanization of countryside labor after WWII…. The list goes on! But it still has that same truth at its heart; what it means to live in those places comes with a complicated mess of cultural inheritance (much of it imbued with struggles of class, race, gender and sexuality) but also emerges from what happens in your life in those places. I guess that’s why I know the rural idyll is a load of bollocks, but also a truly true experience that I had. Kind of.

Yes, this “wide-scope” remembering has value is to remind us that we, each of us, are embedded in the world. In an increasingly atomized and individualized world we need to be reminded we are all together in things, we are connected.

Exactly. And it’s not some kind of esoteric ‘we are all one’ kind of connected - thought of course I’m partial to a bit of that from time time to time - it’s a scrabbling in the field, hard-work, recognizing our impacts on one another, taking responsibility for the effects we have on one another’s lives kind of connected. But learning about that is a process that never ends. This book is me just trying to signal my attempts to recognize some of that through a particular lens.

The book’s title WHERE? is evocative in itself - We and Here and that question mark!

Ha yes! I agonized for ages over what to call the thing. Actually, the title started off as sort of a joke. I’ve moved around a fair bit. I was born in Kent, and at eighteen months old we moved to Surrey; I was four when we moved to Shropshire, eleven when we moved to Buckinghamshire, and since leaving home at 18 I’ve lived in Devon, Cornwall, Wales, and now Bristol. My mum is from Yorkshire but grew up in Kent, and my Dad left home at 17 so I’ve never really lived where my family was ‘from’. So when people ask ‘where are you from?’ they normally get a slightly awkward pause and I tend to say ‘all over the place’ and then when people press they either get a story they really didn’t want because I like to overshare, or I say ‘well, Shropshire is the first place I remember living’. Then they’ll often say ‘where?!’ because that part of the country is kind of not very well known and people haven’t heard of Caynham or Titterstone Clee Hill or whatever. But as I worked on the book more, that sense of the importance of understanding the contingent nature of ‘belonging’ became more and more important to the book so it seemed to fit. Plus Richard McGuire had already taken "Here".

Another powerful strength of WHERE? Is HOW you did all this telling. How did you go about making the images in the book? Did you start with the images and add photos, text and other stuff?

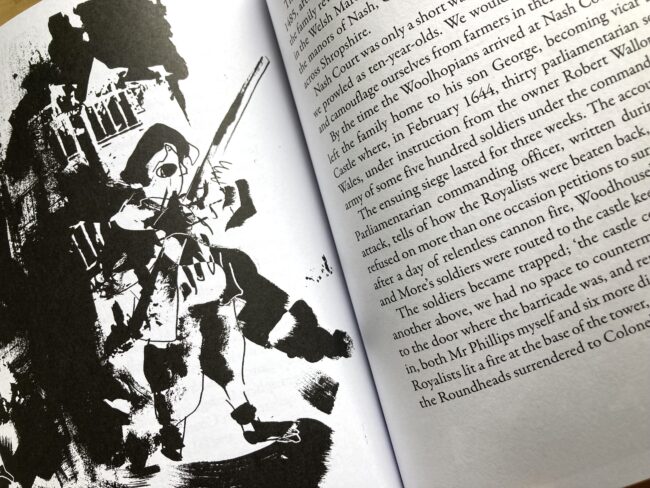

If I’m known for anything outside of our little corner of comics (which I’m not sure I am), I think it’s for being something of a minimalist when it comes to comics - in terms of number of pencil lines and word-count. But I’m sort of done with that, and when I started WHERE? back in 2017/2018, I wanted to try something new. For many of the pictures, I would tend to know what I wanted to draw *about* - a given story, a particular place, or whatever - but not know *how* to represent that, so I would just scribble. I learned that from you, actually; the energy of the first take! So I’d do all these scribbles with a mechanical pencil. I’d then refine some of those, use a lightbox or whatever, or some would stay as they were. That was all on basic office paper. Then I’d use children’s paints - poster paint we call it over here - to do a layer of black on a separate sheet that more or less corresponded with the drawings. I’d then scan those in and assemble them digitally. If they feature photographic elements, I’d add these in then. It was very much trial and error and nothing was pre-planned beyond the initial idea behind a drawing. Of course some are more refined than others, but I didn’t want to agonize over them too much. Then some of the drawings - the flowers for example near the end of the book - were all reproductions of drawings I did in our garden or in my parents’ garden during Dad’s illness. Some of the drawings were done just using paints and edited down in Photoshop. It’s all very much collage which I think is my new favorite thing. Also included are some drawings I made when I was a child.

Were there bits and pieces you sewed together to make the whole thing?

Yes! So the process was iterative - I’d write a bit, draw a bit, change a bit of writing, add in a drawing. I’d have sequences that I knew would work together as comics - the book is a square format so mostly they are full-page pictures, like a picture book - or I’d have images that I knew would act as illustrations. The distinction I make there is that, to me, illustrations relate more directly to the prose, providing a visual interpretation of something happening in the text, whilst as the sequences are comics because they are their own story. It’s not a hard and fast distinction of course. There are also a lot of call-backs set up between word and picture - a story about a historical figure in the prose will come back again in an image, or a series of images will give a slightly different slant to some text elsewhere in the book. That’s a really important component of the work, and one I hope I haven’t made too oblique.

This reads as an expanded idea of comics, where images and words rub together to make something new. I’m reminded of your earlier, more directly “poetic” work where the details drawn (or in this case written) add up to more than the surface sum. You mentioned collage - there’s also careful curation in the book. Were there any parts that surprised you about how they did or didn’t come together?

Perhaps not in terms of individual images or sequences; as it was all very trial and error, there were a lot of pictures that got scrapped as I went along and I expected that to be the case. The bits that didn’t come together were more in relation to specific anecdotes or whatever I thought would fit in the book, but ultimately didn’t. For example, in about 2013 I did an issue of my comics-zine SMOO that comprised three minicomics, and a map, bound with a belly band. Each of the little zines explored a different aspect of growing up in Shropshire. I think one was about the landscape, one about childhood events, and the other about a recent visit or something like that. I thought that these would provide good source material for WHERE? so I went back to those old comics but found I couldn’t use anything for WHERE? that I had already drawn about. One exception is a reworked silent comic about playing in the woods with my brother. Nothing else worked - the comic about exploring the abandoned mansion house, the comic about seeing the fireball… I just couldn’t make those work in the final book. It was as if the comics from 2013 had crystallized those stories, and I would have to find a new way into them if I wanted to tackle them again; I’ve always seen drawing comics as documentation, and it’s not surprising that I wouldn’t feel connected to the way I interpreted something when I was 29. But I was still surprised!

In terms of curation, I definitely like the idea of the whole being more than the sum of its parts - I think that issue of SMOO was an early attempt at that and it’s something I always tried to achieve with all my work since, I think. I’ve always agonized more over the sequence of things in my zines than I have the things themselves, probably! I mean, I could have probably split the book in half and released it as a graphic novel and as a prose book. But it wouldn’t be what it is. Actually, I don’t think you could do that.

This book has an interesting publishing history - it started out serialized in your series Minor Leagues, then was collected in a homemade tome and finally the published book. Can you tell some of that tale?

I’m very much a committed self-publisher. When I started working on what would become the book, it made absolute sense that I’d serialize it in Minor Leagues. That’s something lots of us in this part of the comics world are used to. I also wanted to serialize it so that I would actually finish it - making zines, to me, is all about getting the work out and done before you can second-guess yourself. In the end, it took up four issues - 6 to 9 - of Minor Leagues. Each was about 100 pages in length, square format, printed at home on my laser printer, side-stapled with hand-folded french flaps for the covers. The first two I spent finding my feet, but by the last two I knew what I was doing. I released those across 2018 and 2019 through my subscribers and zine distros and comics shows when they existed.

I also always knew that I wanted it to be published as a book, so in 2020 I took the four installments of the book, chopped and changed bits, moved things around, cut things out, added in some new bits, and produced a handful of homemade books. Big hefty things. Made a book press out of carriage bolts and some wood I had in the shed, lots of PVA glue and book tape. I sold a few of those, gave a few away, and used them to pitch the book to publishers and agents - one of which I got and one of which I didn’t!

Reading each version as you released them (zine, homemade book, published book) was like a peek behind the curtain as you made and remade this narrative to fit the format you were working with and to further focus in on what you wanted to say and how you wanted to say it. Were there any surprises in that process?

I’m quite a harsh editor. I cut out a lot from the earlier installments of WHERE? that just didn’t fit and didn’t feel squeamish about it. I knew it would happen. I spend a lot of time thinking - to the point of disappearing into a fugue state mid conversation! - about the work I make and how it will work or not work. Which isn’t to say it’s planned - the production is spontaneous - but the ingredients are very carefully iterated and put together. That said, at the 11th hour, not long before the book was going to print, I changed a bunch of sequences around again. So I may be a brutal curator, but given the chance, I’ll be an eternal fiddler.

This might be a stretch, but in a book so tied to rural life and the landscape it is so nice that the ink on the final published book is so richly fragrant. Like soil!

Hahah I love the smell of the book! When the publisher said they were going to get it lithograph printed - which is a wet ink process, rather than digital which is all powdery - I was so excited because I knew it would smell amazing. It smells like a high school art room or a gallery or something. Makes me feel dead fancy. But yes, the physicality of whatever I make is very important to me, whether zine or book, so having something as beautiful as that come out the other end is pretty amazing. Plus I’d only ever seen the images on a screen or printed on a crappy laser printer with poor black coverage, so actually seeing the artwork as intended was a kick! Also I got to design the covers which was a lot of fun.

It’s heartening to see a book like this out from a publisher who is not known primarily for comics, zines or art books. How did you get with Little Toller to have WHERE? published?

Little Toller are an independent literary publisher based in the SW of England. A great deal of their output focuses on landscape and nature writing, prose that explores questions of memory and memoir in relation to place - which has made it a great fit for this book. Another author, Max Porter, who had read the homemade book version of WHERE? put me in touch and they jumped at it. They’ve been absolutely great to work with and really understand the book, and although it’s new territory for them, in some respects, because of all the pictures - and new territory for me because of all the words - it’s been fun to learn together.

I’m on record as being ambivalent about publishers representing a kind of panacea to aspiring artists, as being the thing that will solve all your artistic challenges and make you a star, so I wanted to work with someone who had similar ideas to me about how to go about releasing work. The great thing about Little Toller is that they have a very comparable ethos to what I’ve learned in the zine world - grow your audience from the reader up, strong connections with other publishers, vendors, and artists, but also with a strong understanding of how the publishing world works. I can’t really say enough nice things about them.

I got rejections from a couple of comics publishers before that but to be honest I was kind of relieved. I must say - and this may be unpopular - that it was very important to me that the book didn’t come from a comics’ publisher. The main thrust of the book is about grief, place, memory, landscape, nature, history, memoir - these are established areas of literary work where I think many of the readers I couldn’t reach through comics would be. I wanted WHERE? to reach that community directly - to be commercially categorized by its genre and not by its format, as is the curse of so many comics and graphic novels. I wouldn’t be so vociferous about this if I didn’t know that in nearly all non-specialized bookshops, graphic works end up in the back next to the sci-fi and fantasy work, regardless of what they’re actually about.

How do you see WHERE? in the larger body of your work? Both the scope and the formal ways of telling the narrative seem to me related to but stretching what you have done before.

WHERE? is very much the start of a new thing. Or perhaps it's the gateway thing that sort of defines a threshold between what I used to do and what I’d like to do next. I definitely see my work to date in phases - the early issues of my SMOO back in 2007-2011, then the issues from 2012 that got collected as Days by Avery Hill Publishing, then the era that culminated in Plans We Made my graphic novel from Uncivilized in 2015, then the first five issues of Minor Leagues, and then the WHERE? era and so on. Basically, doing this book - which involved loads of research and digging around in physical and digital archives and old books and scouring the world for mentions of Titterstone Clee Hill or whatever, has renewed an intellectual and artistic interest in stuff that I’ve always loved that has been dormant - place, history, identity, memory, all that stuff. These days I’m reading about folklore and ghosts, about boring local history, spending time in archives, trying to find out more about the strata of time and people and things we live amongst and why that matters now.

It’s also reinvigorated my more specifically visual work. I did a book for the wonderful Ley Lines series in 2020, called Lie of the Land which combined old photos, found text and my own drawings/paintings to explore the myth of the rural idyll via the work of Alfred Watkins, originator of the theory of ‘leys’. I followed that up with another zine in the same format called What is Britain? which uses the same techniques to critique the shit-show that is the UK right now, and its politics and position, its attacks on anyone who is not wealthy or white, and a sort of national identity that just buys into the myth that those in power ‘know best’. I think I might make a few more zines in this vein and make it into a miniseries.

I’ve just finished work on Minor Leagues 11, which is a bunch of prose and collage, and now I’ve done that I’m getting down to work on something new, the difficult second album… not sure what it’ll be yet. At the moment I’d like to do a purely prose work, but I’ll never not be doing stuff with pictures alongside that, and I’ll continue to self-publish as much as I can, too. When I have time, of course; I work full-time for a university and none of the fun stuff pays the bills.

That’s another question I always have for artists - how do you do this work? Most of us making work of whatever kind have other ways of making a living, plus families and other interests. How does making intense work like this fit into your day?

I’m an academic by day, working full-time on projects that are to do with the creative and cultural sector and how we can make those more equitable and resilient places to work. I’m lucky to be working in a role I enjoy, with people I respect, doing work that I hope can make a difference. Academia in the UK is a precarious affair, and far less well-paid than it can be in the US. You take time out to do your PhD while your peers are establishing remunerated careers, and scrabble for work after that - it can be very hand-to-mouth and that process took about 6 years or so I think, until I was about 29. Before that I was working in cafes and bars and retail and clerical work, but I didn’t start making comics until after I had started my PhD, in about 2007.

I used to say I wouldn’t give up working to make art, but now I think I’d like to. I just can’t afford it, and as long as that’s the case, I’m lucky to be doing something I enjoy. But I’ve been where I am for nine years now. While tenuous, after a while academia can afford you a lot of other things which are invaluable - a degree of relative stability and a chance to grow and develop and meet people connected to your world and interests, which is really important. These days I work on big projects, I manage people, I have plenty of responsibilities, so non-work where I have energy is becoming a bit more scarce. But I’m married, we have two incomes, and we don’t have kids so that means our lives are slightly more flexible.

So this work fits in around that, and my practice has developed to fit in. On a practical basis, I just draw or write when I can. Writing tends to come to me in spontaneous bursts, so I’ll write them on my phone, or on the computer while I’m doing other things. I draw whenever I can, but only if it has a purpose - unlike you I can only draw if the drawing is going to end up somewhere - in a zine or something. So when I was doing WHERE? I’d go to a cafe in the morning before work and do an hour’s writing, or take a day off work here or there, or I’d draw in the evenings and on the weekends. It’s partly why I started drawing so quickly; I just couldn’t have made things if I was spending hours and hours on a conventional comics page. As for the business side of it - fulfilling orders and printing and the stapling zines - that’s harder to keep on top of but also more demanding. So that fills up time. But it comes in waves - once a new thing is out I know there’s a bunch of admin work to be done, but I’ll be artistically sated for a bit, then that’ll subside. I tell you what, making the installments of WHERE? on a regular basis nearly broke me! I probably shifted about 100 - 150 copies of each issue over the years, which isn’t a huge print run, but it’s a lot of work. They’re out of print now, so I’m glad I don’t have to make them anymore and can focus on new ridiculous projects instead, while the book version of WHERE? now exists as the definitive, one-volume edition I had always hoped it would be.