No links today. Instead, here are some scattered thoughts on comics I've been reading. I suppose it's a somewhat conservative list, but it's what is at hand at the moment, and what I felt like writing about. There are lots of things missing but, y'know, I only get this energy going every so often, so here goes...

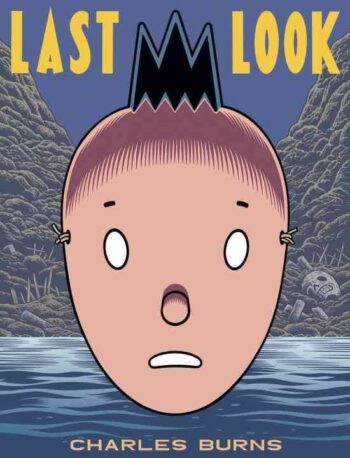

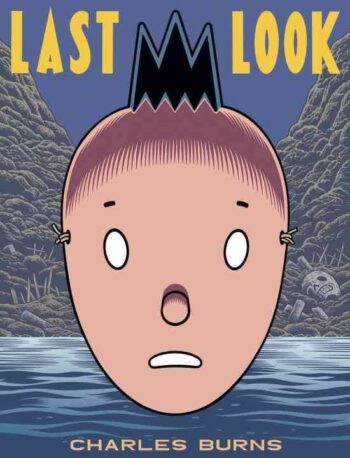

Charles Burns: Last Look

What a thing. I know this was completed two years ago, but reading the three books in a single volume is an entirely different (and recommended) experience. It does not let the protagonist, Doug, off the hook for his recklessness. His culpability in the emotional devastation he has caused is not excused. It is explored, relentlessly, in the only terms available to him — comics, a la Herge and Romita. And Burns’ empathy allows the sub-narrative, which tracks Nitnit (a Doug dream figure) in a beige-hued nightmare world, to flourish. Formally, there is so much about comics in there, in the sense of image repetition and immersion/escapism.It’s one of the best graphic novels I’ve ever read. And the larger project around the book (Johnny 23, the Nit Nit portfolio, the current books from Cornelius, Vortex and Love Nest) make this a territory richer than any Burns has explored. It’s like he just keeps going, and makes us realize how an artist can blend aesthetic and procedural obsessions (here I think of Burns’ Marvel Try-Out Comic as key to Last Look) with an emotional core that clearly keeps this moving forward. The images in these other projects continue the world of Doug's obsessions, but blend them with the author's creating a kind of meta-fictional art that thrums with authenticity and urgency.

Vanessa Davis: Summer / Autumn Hours (online only)

These are among the most naturally funny and heartbreaking comics being published today. What strikes me the most is Vanessa’s natural line and sense of space and color. It’s a kind of calligraphic approach that seems informal, but could come with years of practice. She’s able to condense so much emotion and wisdom into a few pages. With the basic backdrop of the summer season as her narrative thread, Davis takes us through memories, physical transitions, and geographic relocations, all in an even tone, from comedy (the peculiar problem of sweater weather and the definitions of fancy) to real sadness (an elderly parent, a dead one; intense anger). In Davis’s work, an umbrella base becomes totemic in a tough, and not at all romantic way, and the habits of beavers provide some comfort in dealing with humanity’s foibles. I love these comics. Also remarkable is that the Paris Review is regularly running comics on its web site. And phenomenal comics, too.

These are among the most naturally funny and heartbreaking comics being published today. What strikes me the most is Vanessa’s natural line and sense of space and color. It’s a kind of calligraphic approach that seems informal, but could come with years of practice. She’s able to condense so much emotion and wisdom into a few pages. With the basic backdrop of the summer season as her narrative thread, Davis takes us through memories, physical transitions, and geographic relocations, all in an even tone, from comedy (the peculiar problem of sweater weather and the definitions of fancy) to real sadness (an elderly parent, a dead one; intense anger). In Davis’s work, an umbrella base becomes totemic in a tough, and not at all romantic way, and the habits of beavers provide some comfort in dealing with humanity’s foibles. I love these comics. Also remarkable is that the Paris Review is regularly running comics on its web site. And phenomenal comics, too.

Steven Weissman: Looking for America's Dog

Looking for the perfect cure to post-election blues? This is it. Weissman delivers his best book yet, in this odd, entrancing collection of linked short comics on the theme of Bo, the presidential dog. I'm still trying to figure out how to explain this thing. It's like a series of campfire stories, almost, sweet at first, but often acidic -- there is darkness here, as symbols of hope get lost, mutate and become sometimes sinister. Great, textured cartooning with the best use of zipatone this side of Wally Wood.

Ted Stearn: Fuzz and Pluck: The Moolah Tree

I have loved Ted Stearn’s work since his Rubber Blanket days, and this is a wonderful book. I would even go so far as to say it’s practically the best book you could give to someone you love, simply because it’s so full of kindness, beauty, and incredibly funny, brilliant cartooning. It’s a yarn, a la Carl Barks and Charles Portis, in which Stearn’s longtime protagonists, Fuzz (a bear) and Pluck (a chicken) embark on an epic quest a “moolah tree” that, of course dispenses cash. The foolishness of such a task, and the many people they encounter along the way (including two of my favorites kinds of characters: hippies and pirates) each present their own difficulties and pleasures. I liked spending time with everyone and everything in this book, and that is partly due to the incredible artwork. It seems like Stearn has set the whole thing in a 17th century Flemish landscape, its terrain meticulously detailed, and every structure perfectly rendered. But it never feels like “background” material — it’s fully integrated as cartoon drawing, so you can fully immerse yourself in his world.

I have loved Ted Stearn’s work since his Rubber Blanket days, and this is a wonderful book. I would even go so far as to say it’s practically the best book you could give to someone you love, simply because it’s so full of kindness, beauty, and incredibly funny, brilliant cartooning. It’s a yarn, a la Carl Barks and Charles Portis, in which Stearn’s longtime protagonists, Fuzz (a bear) and Pluck (a chicken) embark on an epic quest a “moolah tree” that, of course dispenses cash. The foolishness of such a task, and the many people they encounter along the way (including two of my favorites kinds of characters: hippies and pirates) each present their own difficulties and pleasures. I liked spending time with everyone and everything in this book, and that is partly due to the incredible artwork. It seems like Stearn has set the whole thing in a 17th century Flemish landscape, its terrain meticulously detailed, and every structure perfectly rendered. But it never feels like “background” material — it’s fully integrated as cartoon drawing, so you can fully immerse yourself in his world.

Lynda Barry: Greatest of Marlys

The single best case for Lynda Barry’s important and greatness as a cartoonist. It gathers such versatile material all performed in a similar format, and with such verve. You don't need me to tell you to get this book. Just get it. Your life will be better.

The single best case for Lynda Barry’s important and greatness as a cartoonist. It gathers such versatile material all performed in a similar format, and with such verve. You don't need me to tell you to get this book. Just get it. Your life will be better.

Chester Gould: Dick Tracy: Colorful Cases of the 1930s

Is this how it’s done? Damn near perfect. Great scholarship, perfect selections. I just want more writing about the visuals. I can never have too much. It’s actually thrilling to watch Gould’s cartoon language develop in a single book — you watch him grow into a masterful stylist and you see the Tracy world coalesce. This one is absolutely essential.

Is this how it’s done? Damn near perfect. Great scholarship, perfect selections. I just want more writing about the visuals. I can never have too much. It’s actually thrilling to watch Gould’s cartoon language develop in a single book — you watch him grow into a masterful stylist and you see the Tracy world coalesce. This one is absolutely essential.

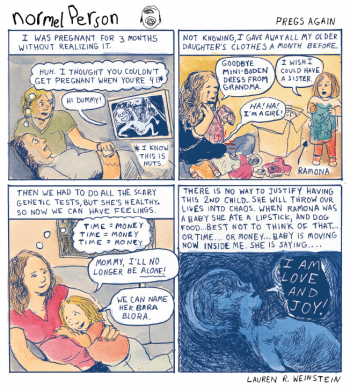

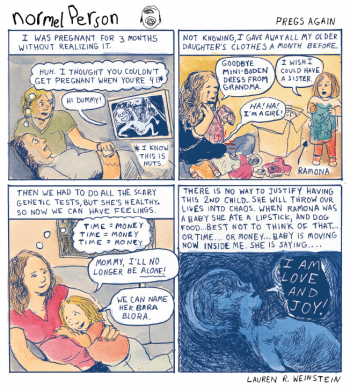

Lauren Weinstein: Normel Person Comics (online and in The Village Voice -- click through online)

I, like Lauren and her husband, my pal and co-editor, Tim Hodler, am a "normal" person in the sense that we just can't fucking believe what is happening around us but we are self-aware enough to understand the absurdity of that luxury. I think. Normal here opens up to move away from the old "white straight guy" meaning and into a whole mindset of viewing the world and asking simple, structural questions and funny, moving observations. Halloween costumes, babies, food. The basics of our particular little kind of life. All done in Lauren's detailed line work and lush watercolors. A master at work.

I, like Lauren and her husband, my pal and co-editor, Tim Hodler, am a "normal" person in the sense that we just can't fucking believe what is happening around us but we are self-aware enough to understand the absurdity of that luxury. I think. Normal here opens up to move away from the old "white straight guy" meaning and into a whole mindset of viewing the world and asking simple, structural questions and funny, moving observations. Halloween costumes, babies, food. The basics of our particular little kind of life. All done in Lauren's detailed line work and lush watercolors. A master at work.

Jonathan Chandler: You Are Crumbling All My Jonathans

A great pamphlet from Jonathan Chandler, who depicts a monologue directed at the reader. It's genuinely frightening, in a Kubrickian way. We are confronted with an aggressive, angry man who taunts us and another being, and preys on our inaction. Really good work, as usual.

Jonathan Barli: The Gaze of Drifting Skies: A Treasury of Bird's Eye Cartoon Views

This book contains early-to-mid 20th century illustrations that seem to fall under the header of “single image narrative”. Barli seeks to establish these cartoons as a genre, but offers no proof other than, um, saying they’re a genre and citing Bruegel. Does Eric Fischl count? What about Chris Ware? I dunno. Some are, indeed, a bird’s eye view (i.e. seen from above). Others are from the ground, others are underneath the ground. Others are on a staircase. Barli pulls together some very rare images by rarely reproduced artists and then, um, doesn’t offer any biographical or bibliographical information. Like, none. He managed to over-design the shit out of the book, complete with a pointless die-cut and odd references to Jules Verne, but no actual information on the art he’s collecting. I get that it’s a nice gift book and quite a difficult thing to even find all the material, but smart merchandizing and rudimentary scholarship needn't be mutually exclusive.

Stef Sadler: The Kimberly Toilet Files

I couldn't find an image of this cover online, or anyplace to buy it, but hopefully one of those Sadlers will tell me. This is a change of pace for Stef, chronicling the daily life of Kimberly Toilet, who works at a "Sports, Spa, Soap" store. Kimberly is monitored, tormented, bothered, and altogether frustrated by post-Internet society. Told in a crisp, digital style -- very funny and sweet and altogether a descended of some 2000 AD backup feature that was too good to be published.

Jessica Campbell: Hot or Not: 20th Century Male Artists.

l love this little book that does exactly as the title suggests: breaks down male artists into the ol' "hot or not" categories usually reserved for women, even, or even especially in the art world. Campbell nails the silly "objective" tone of it all, digs deep in her choices, and is very, very funny. Also, her unfussy, to-the-point cartooning removes any sense of artifice. The book moves along easily and you barely stop to realize how funny, weird, and uncomfortably natural it all feels.

l love this little book that does exactly as the title suggests: breaks down male artists into the ol' "hot or not" categories usually reserved for women, even, or even especially in the art world. Campbell nails the silly "objective" tone of it all, digs deep in her choices, and is very, very funny. Also, her unfussy, to-the-point cartooning removes any sense of artifice. The book moves along easily and you barely stop to realize how funny, weird, and uncomfortably natural it all feels.

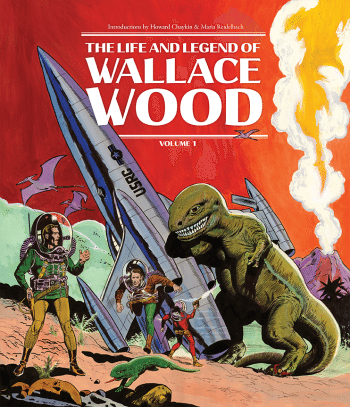

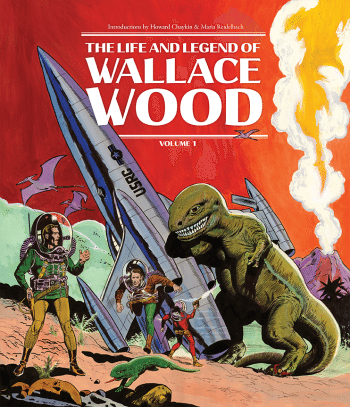

Wally Wood Department:

Bhob Stewart and J. Michael Catron, editors: The Life and Legend of Wally Wood

What is this book? Nothing in or on it gives any clue. It is the latest in what is arguably a glut of Wally Wood publishing activity. This one is based on Bhob Stewart’s wonderfully eccentric volume from a decade back. That one, a shabbily printed paperback apparently divested of swear words and nudity by its publisher, was a shambling compendium of essays, interviews, memories, and biographical anecdotes. It was no more and no less than an old school fan’s memory book. It worked, and was a great resource for further writing on Wood. This one, somehow based on Stewart’s (though there’s no indication of that previous book outside of a one-line mention in the colophon) and with an additional editor, J. Michael Catron, but with no indication of Catron's relative contributions. The cover boasts of introductions by Howard Chaykin and Maria Reidelbeck, which is practically a distress signal. This is clearly for comics nerds of a certain age. And that's a shame, because Wally Wood, inarguably one of the greatest, strangest and most interesting comic book artists of the 20th century, has influenced a tremendous amount of visual culture, from superhero and SF comics to Robert Crumb to Kerry James Marshall to Elizabeth Murray to Gladys Nilsson to Mike Kelley to Dan Clowes to George Lucas to Sue Williams. Let’s pretend you’re a historian and you’ve noticed how a few cartoonists keep popping up whenever contemporary painters discuss their influences — Crumb, Wood, Wolverton, Kirby. Let’s take the next step and see if you can find anything of worth written about them. Wolverton you have, thankfully, Greg Sadowski’s Creeping Death. With Crumb you have a ton of interviews. The other two, you’re shit outta luck.

What is this book? Nothing in or on it gives any clue. It is the latest in what is arguably a glut of Wally Wood publishing activity. This one is based on Bhob Stewart’s wonderfully eccentric volume from a decade back. That one, a shabbily printed paperback apparently divested of swear words and nudity by its publisher, was a shambling compendium of essays, interviews, memories, and biographical anecdotes. It was no more and no less than an old school fan’s memory book. It worked, and was a great resource for further writing on Wood. This one, somehow based on Stewart’s (though there’s no indication of that previous book outside of a one-line mention in the colophon) and with an additional editor, J. Michael Catron, but with no indication of Catron's relative contributions. The cover boasts of introductions by Howard Chaykin and Maria Reidelbeck, which is practically a distress signal. This is clearly for comics nerds of a certain age. And that's a shame, because Wally Wood, inarguably one of the greatest, strangest and most interesting comic book artists of the 20th century, has influenced a tremendous amount of visual culture, from superhero and SF comics to Robert Crumb to Kerry James Marshall to Elizabeth Murray to Gladys Nilsson to Mike Kelley to Dan Clowes to George Lucas to Sue Williams. Let’s pretend you’re a historian and you’ve noticed how a few cartoonists keep popping up whenever contemporary painters discuss their influences — Crumb, Wood, Wolverton, Kirby. Let’s take the next step and see if you can find anything of worth written about them. Wolverton you have, thankfully, Greg Sadowski’s Creeping Death. With Crumb you have a ton of interviews. The other two, you’re shit outta luck.

Anyhow, back to this thing. It seems to be chronological, but there’s no narrative through-line and no hierarchy of content. For example, four pages are given over to unpublished very rough sketches for an-unpublished edition of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, and the accompanying text by Stewart includes a complete account of that books’ hollywood fates. Diane Dillon’s moving account of her friendship with Wood is only 3 paragraphs and yet given an entire spread. We get four pages from Rick Keene ostensibly about trading cards Wood did for Topps, but it’s mostly about Keene’s own childhood. Six pages are devoted to TwoMorrows’ removal of some nudity in the first edition. There are interviews with John Severin and Al Williamson that provide little insight. You see where I’m going here. This thing is just a mess. There’s no sense that one piece of text (and corresponding work) is more important than another. There are multiple overlapping essays on Mad and EC, with little attempt to differentiate them. The best essays are those that attempt to understand Wood as a working artist and a human being, like Russ Jones’ moving memoir, West 74th St., and Ralph Reese’s account of his life as an assistant to Wood, “When in Doubt, Black it Out”

Then there is the bizarre art direction: Some images are printed as line art, some as objects, with no apparent guiding principle. Catron takes pains to tell us that Wood developed the visual look of Daredevil's sensory powers, but offers no visual examples. Numerous spreads are taken up with black and white reproductions of comic book pages printed too small (four to a page) to actually get anything from. Most of the color EC work is shown in contemporary digitally colored form, which is especially odd since that mode is particularly unkind to Wood’s linework. If you picked up this book hoping to see good examples of Wood’s art, you’d be sadly mistaken.

What you never get is any kind of evaluation of Wood’s talents. What made him unique? What was he best at doing? What this book needed was someone to look at it and say, “what are we trying to do here, and what’s the best way to accomplish this”? If the goal was to show Wood’s progress, it fails. And there’s no hint of what Volume 2 contains.

Worse yet is the collection of Wood’s western strip, Shattuck, which was completed for a military newspaper in 1971. It’s unclear, and editor David Spurlock never says, what exactly Wood contributed to this strip aside from an idea. The aforementioned Howard Chaykin, as well as Dave Cockrum, did a lot of the art. Chaykin tells the story of this strip better in his own introduction to The Life and Legend than David Spurlock does in his. This is miserable, poorly drawn, and charmless work (even by my very forgiving standards), replete with pointless violence, rape fantasies and the like. Wood did a lot of dreck, but it was almost always beautifully finished. For unexplained reasons the art is reproduced from the original boards, like an “artist’s edition” which makes it look even worse. So why even publish this thing? There’s nothing to be learned about his work here — no entertainment value. There’s so much great work of his to be published nicely — the only thing Shattuck shows is how low Wood (and, I would guess his estate manager) could go. A sad affair all around.

Worse yet is the collection of Wood’s western strip, Shattuck, which was completed for a military newspaper in 1971. It’s unclear, and editor David Spurlock never says, what exactly Wood contributed to this strip aside from an idea. The aforementioned Howard Chaykin, as well as Dave Cockrum, did a lot of the art. Chaykin tells the story of this strip better in his own introduction to The Life and Legend than David Spurlock does in his. This is miserable, poorly drawn, and charmless work (even by my very forgiving standards), replete with pointless violence, rape fantasies and the like. Wood did a lot of dreck, but it was almost always beautifully finished. For unexplained reasons the art is reproduced from the original boards, like an “artist’s edition” which makes it look even worse. So why even publish this thing? There’s nothing to be learned about his work here — no entertainment value. There’s so much great work of his to be published nicely — the only thing Shattuck shows is how low Wood (and, I would guess his estate manager) could go. A sad affair all around.

Better, however, is Roger Hill’s Galaxy Art and Beyond. Hill contributed two excellent essays to the Life and Legend book, and here we get all of Wood’s astonishingly beautiful SF illustrations produced between 1956 and 1962. Hill wrote a detailed introduction that goes into the publishing history of Galaxy and other SF magazines, Wood’s relationship to them, and even Wood’s drawing techniques, this last bit being particularly invaluable. Like many other authors coming out of Boomer fandom, Hill doesn’t do much aesthetic evaluation, preferring a “just the facts” approach, but the facts here are deeply researched and well organized. The book itself is a tad crowded — with sometimes a half dozen drawings on a spread, but I’ll take what I can get. When the layout opens up and we get a full page or full spread illustration, it sings. This work was Wood right between his ultra-detailed EC period and his streamlined 1960s work. He’s at his peak in terms of design, brushwork, and spatial rendering. When we think of what SF looked like in the middle of the 20th century, this is it. Grab this one for a real masterclass in what Wood could do.

Better, however, is Roger Hill’s Galaxy Art and Beyond. Hill contributed two excellent essays to the Life and Legend book, and here we get all of Wood’s astonishingly beautiful SF illustrations produced between 1956 and 1962. Hill wrote a detailed introduction that goes into the publishing history of Galaxy and other SF magazines, Wood’s relationship to them, and even Wood’s drawing techniques, this last bit being particularly invaluable. Like many other authors coming out of Boomer fandom, Hill doesn’t do much aesthetic evaluation, preferring a “just the facts” approach, but the facts here are deeply researched and well organized. The book itself is a tad crowded — with sometimes a half dozen drawings on a spread, but I’ll take what I can get. When the layout opens up and we get a full page or full spread illustration, it sings. This work was Wood right between his ultra-detailed EC period and his streamlined 1960s work. He’s at his peak in terms of design, brushwork, and spatial rendering. When we think of what SF looked like in the middle of the 20th century, this is it. Grab this one for a real masterclass in what Wood could do.