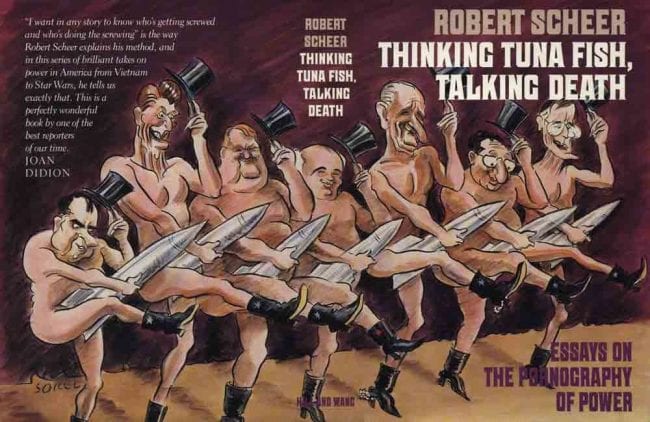

Now in his eighties, Edward Sorel has had a career that is the envy of most cartoonists and illustrators. His long career has included a significant body of work for magazines like The New Yorker, Vanity Fair, The Atlantic, The Nation, Ramparts and The Realist. He was a co-founder of Push Pin Studios with Seymour Chwast and Milton Glaser. He’s a muralist, children’s book author, has illustrated dozens of books, and has been the subject of an exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery.

Now in his eighties, Edward Sorel has had a career that is the envy of most cartoonists and illustrators. His long career has included a significant body of work for magazines like The New Yorker, Vanity Fair, The Atlantic, The Nation, Ramparts and The Realist. He was a co-founder of Push Pin Studios with Seymour Chwast and Milton Glaser. He’s a muralist, children’s book author, has illustrated dozens of books, and has been the subject of an exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery.

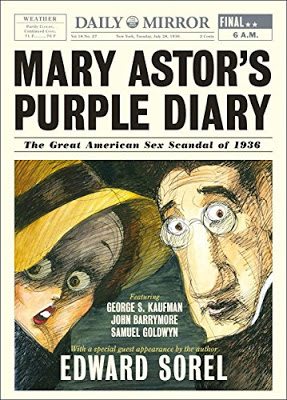

His new book is Mary Astor’s Purple Diary: The Great American Sex Scandal of 1936. The heavily illustrated book tells the story of the actress best known for playing Brigid O’Shaughnessy in the 1941 film The Maltese Falcon. Astor was raised by a nightmare of a father, started working in Hollywood during the silent film era, was married multiple times. Her divorce trial in 1936 featured her “purple diary” which detailed her colorful personal life. It serves as a portrait of a very different time in ways that are both funny and puzzling. Sorel’s book is not just a straight up biography of Astor, but also his story as well and is heavily illustrated with what his fans will recognize.

I loved Mary Astor’s Purple Diary, and it was a revelation because when I think of Mary Astor I think of Brigid O’Shaughnessy, which I think is what most people think of when they hear her name.

The knock that she gets for The Maltese Falcon is that she was too old, or at least that she looked too old. Her alcoholism did age her a bit as she was only 30 when she made the movie, I think. She looked a little older. The real problem I think was that the Hays Office, with their insane censorship, did not allow Huston to show a sufficient amount of sexual passion to make the plot plausible. That final scene where he tells her that he’s going to turn her in, you’re supposed to feel that he’s really torn between turning her in and saving her because he really is passionately in love with her. There was nothing in the movie that showed it or made you feel it. I think there’s one kiss that ends with him looking out the window. So I don’t give her a knock. I think she was plenty sexy. I think it was more the censorship rather than her age that was the problem.

You make the point in the book that she was a good actor, but she made few good movies.

Very few good movies. Aside from Dodsworth, which to my mind was the greatest of all her movies, there are very few. I suppose she always acquitted herself as best she could, but the movies themselves are not worth watching. I was criticized by one person for not including The Palm Beach Story in my book but I thought that was basically a pretty silly movie. But beauty is in the eye of the beholder.

I love Preston Sturges, but I agree with you about The Palm Beach Story. Besides Dodsworth and The Maltese Falcon, Red Dust is interesting but not great, and I love Meet Me in St Louis, but Astor is the mom and she’s barely in the film.

That time was her pre-suicide period. She was continually trying to kill herself because she couldn’t stop drinking. That was one of her mother roles.

You talk about how you learned about this sex scandal in the book, but did you know her work from before that when you were younger?

Certainly not. I remember her when I was 10 years old in 1939 in The Prisoner of Zenda because she was just so beautiful. She had the perfect turn of the century Victorian face. I remembered her in that, but no. When you’re a little boy you’re empathizing with male characters rather than female ones so I was more interested in James Cagney or others.

Throughout your career you’ve shown a lot of affection for that era of film.

Yes. As I intimate in my book, because of the studio system you saw the same supporting actors week after week. There was always Franklin Pangborn or Thomas Mitchell or Edward Everett Horton or any number of supporting actors you saw week after week and they became a kind of family. It was a family that didn’t have any conflict. I was always drawn to movies because there was a great deal of conflict in my family in my expanded family. Politically at any rate. Several members of my family were avid communists and they were always castigating the members of my family that weren’t communists, so there was always that conflict in my family.

You mention in the book that you came upon this story decades ago. Why did it take you so long to write the book?

Because I had to make money. I had four children and had to send them through college. I was lucky enough to have lots and lots of deadlines. I made a surprising amount of money, considering. On the one hand I was very, very lucky to go through life making pictures. On the other hand I made a lot of worthless pictures. A lot of the most haunting work an illustrator gets is for advertising and most of that stuff is just worthless. I was doing a lot of that and then suddenly the field came to an end. As the computer took over and as the internet took over there was less and less advertising in print and then print started to vanish. Ten years ago I suddenly realized there’s not much work out there. I was lucky because I was able to create my own ideas and sell them to magazines, but that didn’t produce much income. By the time it utterly disappeared about five years ago I started thinking in terms of finally doing the book I planned to do fifty years ago. It took my three years to do it including a false start that got rejected, but I finally did it and the rewards were much much richer than anything I had done before. Even the murals that I did, which up until my book were the high spot of my artistic life. The book was even more satisfying than that.

What was the false start? What went wrong?

I was doing it relatively straight. I was telling the Mary Astor story and I wasn’t part of the story. As I walked out of my publisher’s office with my rejected dummy one of the assistant editors said to me, you know if you put yourself in the story, it might work. Once I put myself in the story, it was a breeze. It not only became amusing, but it was fun to write. I was having more fun writing it than I ever did drawing. I’ve always said that the only people who enjoy drawing are amateurs. Once you’re a professional, you have certain standards and certain visions of what the drawing should be and you don’t always come up to it. I can’t say the writing was fun, it was hard work, but I took great pride in it. It was my voice and my opinions and I was able to talk to Mary as long as I was in the book.

As someone who knows your work, the writing felt like the way you draw.

You couldn’t have said anything nicer to me. I have always admired spontaneous drawing and I have always hated my drawings because they occasionally got overworked. I have always admired people like [Ludwig] Bemelmans and Feliks Topolski and Jules Feiffer who have enormous energy in their drawings. I admire drawings that have spontaneity, and I don’t always have that. I think probably because my ideas are occasionally very operatic–they have many people in it and many things to explain. It’s very hard to be spontaneous when you have to do a picture with many elements and they all have to come out in the right place.

There are lots of illustrations you’ve made over the years which have lots of elements and I’m picturing many. Along similar lines, the endpapers of the book have a nude Mary Astor reclining with the studios in the background and other elements. How did you decide on that image and assemble it?

The truth is that I love detail and I love reference material and I love swipe material. I do a lot of research. One of the reasons I do so many parodies of art that was done in the past is because the old masters were masters of composition. I’ve always considered composition my weakest skill. To have an old master where the compositions are perfect, it’s great fun to parody. When I was looking for something to do for the endpapers I went to Google and looked at hundreds and hundreds of designs and I must have found something that suggested the naked Mary Astor figure. I’m sorry to say that I can’t remember what my swipe material was. I knew the other elements that I wanted, so it was easy after that. There was the plane crash that her first husband died in and the movie studios she worked for. I have no shame about looking to other artists and other art for inspiration.

That differed a lot from all the interior drawings in the book?

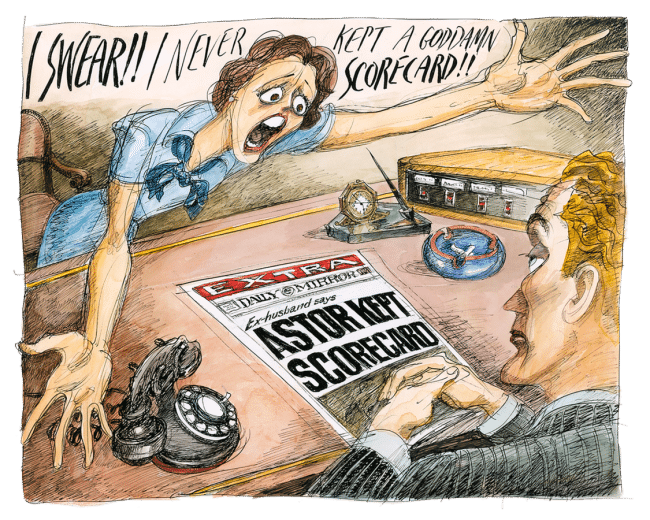

I’m always amused when artists talk about where their inspiration comes from. The truth of the matter is that all of us are terribly influenced by photographs. Citadel Books did a whole series of movie books, paperbacks of different actors and actresses, and I have a lot of them. I never got proper training in life drawing and my mind is not a computer that can produce gestures easily. I need to see certain gestures–and convincing gestures. I think to the extent that my drawings are interesting is that the gestures are interesting. That’s what cartooning and illustration is all about. It’s all about gestures because there are no words–unless you’re a cartoonist doing a comic strip–so the gesture has to really tell the story. I work very hard at gesture. I hope it shows. I hope the labor doesn’t show, but I hope the gestures are convincing.

Why did you chose to draw the interior illustrations that you did?

Why did you chose to draw the interior illustrations that you did?

The great thing about doing a book is that you can pick the scene you want to draw. There was one scene that I knew I had to do–her father attacking her because of what he considered her lack of ambition. I did a kind of strobe shot of his fist banging on the piano. I knew I had to do that even though it was a very difficult picture to do. Then there were the pictures that had absolutely nothing to do with the book that I did because I wanted to. There’s a picture of Tom Mix with some car that was made in Los Angeles that nobody knows about. I did it because it was fun to draw and I had a picture of it. The book was in my entire life this book was more a labor of love than anything I have done before.

I know that you went to art school, but you said earlier that you never studied life drawing?

Because it was impossible. I went into art school at the very time when drawing was considered rather old hat. The illustrations in The Saturday Evening Post were condemned as the lowest form of art, illustrated books stopped, the New York school of abstract painting was considered the acme of fine art. I graduated from Cooper Union in 1951. The good thing about it was there were plenty of jobs and the bad thing about it was that I still didn’t know how to draw. My drawing skill–which was not too bad when I was nine years old–had completely atrophied from going to High School of Music and Art and going to Cooper Union. The thing that was valued was design and abstraction. Which interested me not at all. And still doesn’t. Even though I started Push Pin Studios with Seymour Chwast and Milton Glaser, which was essentially a design studio. I did learn how to do design, but it never really interested me. What I loved was drawing.

You seem to have found a niche of doing illustration fairly early in your career, though. At least that’s how it looks from the outside.

I suppose. Some young people have an image of what they want to become very early in their life. All I ever wanted really was to have my own apartment. When I was a young man I didn’t care how I got the money to get my own apartment, but the truth of the matter is I wasn’t good at anything except drawing. Fortunately I was able to make a life for myself where all I had to do was draw pictures. I was a hack to start out with and gradually became something more than a hack. I regard my early years of working for agencies and working for magazines as being paid to learn. I did what was required and in the process learned how to draw.

You have been for many years now at Vanity Fair and The New Yorker and The Atlantic and The Nation and work that’s above hackwork.

You have been for many years now at Vanity Fair and The New Yorker and The Atlantic and The Nation and work that’s above hackwork.

Well above hack work. I like the work I do. I’m proud of the work I do. But it’s the old line, if you want to be the top banana, you’ve got to start at the bottom of the bunch. One of the reasons I learned to work in pen and ink was because the easiest work to get was work from the newspapers. At the time I started out, there were a lot of newspapers. They didn’t pay very much and the only thing that worked in a newspaper was linework so I had to learn how to do line. And I did.

At the end you make the point that you hope someone will write a full-length biography of Astor, reissue the books she wrote, and put her on a stamp.

Yes. [laughs] I make a presumptuous comparison to Felix Mendelssohn who was instrumental in bringing Johann Sebastian Bach to prominence again. He was a largely forgotten Baroque composer until Mendelssohn showed his the magnificence of his music. I too am eager to remind people that Mary Astor did was a great talent, although the thing that must be said against her was that she did not value her talent. She had been offered many times contracts for leading roles but avoided it because she was afraid that it wouldn’t last long. She knew that as a supporting actress she could have a very long career and in fact she did. Supporting actors can have very long careers, but she didn’t do anything about getting good roles for herself. And it’s a pity.

Like I said before I knew her from a few of her films, but having read your book, she is a fascinating character.

Thank you. I thought so.

And more interesting than most of the characters she played on screen.

[laughs] Yes. A friend and I tried to turn my book into a musical but it proved to be impossible because she was a woman who did not take her life in her own hands. Most musicals are about women who are indomitable, like the Unsinkable Molly Brown or Coco Chanel or others. Instead of doing things, Mary had things done to her which made her an impossible subject for a musical. She still might be a good character for a straight play.

She’s just so passive.

Yes, very passive. Her evil father knocked all her guts out of her. She learned to be obedient and do what others told her to do. She kept marrying men who were the same way–who took control of her and very often exploited her and took advantage of her.

You said that this book is the most satisfying project you’ve ever made. Are you trying to write another book?

I’m trying to figure out a way of doing a memoir that’s amusing and yet says something about the political scene. How we went from triumph in World War II to Donald Trump in the 21st Century. I think we did it by having a series of incompetent and criminal Presidents from Eisenhower on. The only person I exempt partially from that description would be Obama, who I think is a decent and well-meaning person. The other Presidents, every one of them, committed vile criminal unconstitutional acts. Everybody forgets that lovable Dwight D. Eisenhower overthrew at least four democratically elected governments while John Foster Dulles was his Secretary of State, and the others that followed him were no better. I’m going to try to do a memoir in which my rage combines with my pleasant memories of those years.

I’d be interested to read that. Over the years you’ve been willing to step on peoples’ toes.

Only powerful people. [laughs] No point in stepping on the toes of the weak and powerless. But yes, of course. Especially hypocrites. Especially Democrats who say one thing and do another. I had more fun with Lyndon Johnson and Hubert Humphrey than even with Richard Nixon although he was really probably the King of the Hypocrites. I’m more critical of those who are supposedly on “my” side than I am of easily recognizable enemies.

Well, Mr. Sorel, I know that you have to go. Thank you so much for taking the time.

You can call me Ed. I may be old, but I’m just a cartoonist. [laughs]