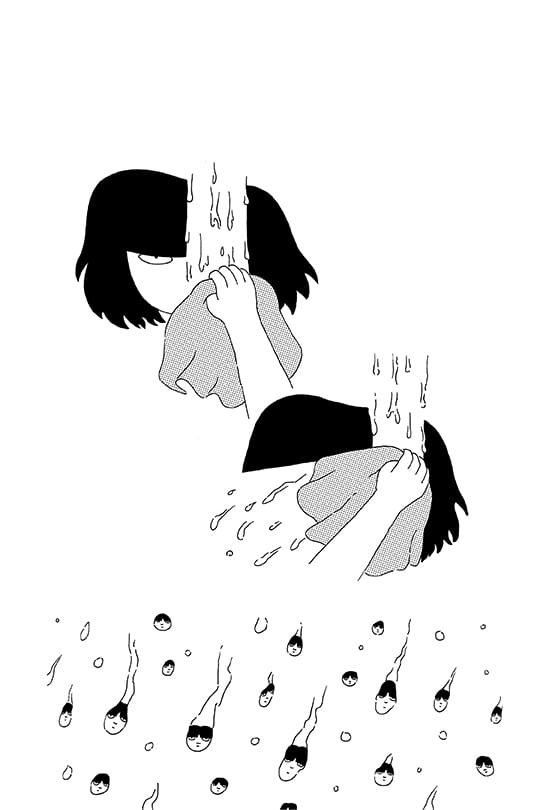

There's a telling sequence early in Daryl Seitchik's debut long-form work, Exits, where the protagonist, Claire Kim, has to deal with being objectified by her boss, the owner of a mirror store. He's looking at a laptop at an image of a curvaceous woman in a bikini with the head cropped. When Claire walks over, the laptop is positioned such that her head is atop the bikini model's body. While she does not see him do this, the scene is a kind of a deadpan and shorthand manner of establishing the way she's seen by her boss, and the effect that it has on her is explored as she washes one of the countless mirrors in his store. Those scenes establish how desperately Claire wants to control how she is seen, and the helplessness she feels in dealing with that gaze that she's well aware of experiencing on an everyday basis. Even worse than that blatant bit of objectification is when he tells her, apropos of nothing, that she looks depressed; rather than offering support or even asking that she get help, he tellingly says, "No one wants to see that." It's another deadpan moment where at first it seems like he is expressing genuine concern for a moment but then quickly reveals that her actual welfare is unimportant to him. It is another way for him to control how she is seen and what her image looks like, an attempt to mold her into something that is more pleasant for him and his customers to look at. Not only is he objectifying her, but he is also viewing her as a commodity, as a thing that would help him sell other things. Her only means of resistance at this point in the story is to not voluntarily contribute to her objectification by pretending to be happy and perky. What it means to be seen in relation to one's identity, especially as a woman, is at the heart of this book.

Seitchik's work has always addressed isolation, alienation and the nagging sense of anxiety that comes when one doesn't feel like they fit into society. That sense of alienation in part addresses her status as a woman and the othering that is experienced on a daily basis, but there's a more existential level to it as well. The classic problem of existentialism as a way of understanding the world is that it has absolutely no connection to ethics, the central question of which is "What do we do about others?" I might exist, but how do I connect with others, especially in a world where so many human relationships are what the philosopher Martin Heidgegger might describe as Zuhandenheit, or "ready-to-hand". That is, we think of others as a means to an end and not unlike other objects in the world that have a certain function. Claire is someone who has come to the end of her willingness to be that object.

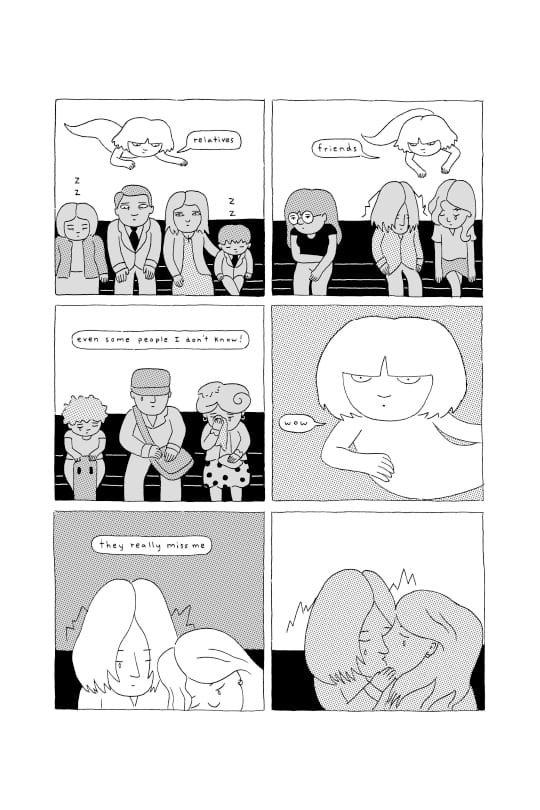

At the beginning of the story, Claire is working at a mirror store, hating her boss, the clientele and the constant reflection of images. There are telling images early in the book where she's wiping off the surface of a mirror, at once reflecting and erasing her own existence. She fantasizes about her own funeral (a different impulse than fantasizing or ideating about her death), a hilarious sequence where she's impressed by the turnout, weirded out that a couple of people start making out in the middle of the funeral and chastised by a friend who reminds her that she's not dead. This fits right into the title of the book, as death would be one exit out of life. That's followed by an absurd but terrifying sequence where she's chased by "a giant man-baby", kind of the essence of the male id. That causes her to suddenly turn invisible, allowing her to turn the tables on her attacker. To be sure, turning the tables on the man-baby spoke to the way in which gender was one part of her sense of alienation, but Seitchik soon strips away that layer to explore other layers of self.

At the beginning of the story, Claire is working at a mirror store, hating her boss, the clientele and the constant reflection of images. There are telling images early in the book where she's wiping off the surface of a mirror, at once reflecting and erasing her own existence. She fantasizes about her own funeral (a different impulse than fantasizing or ideating about her death), a hilarious sequence where she's impressed by the turnout, weirded out that a couple of people start making out in the middle of the funeral and chastised by a friend who reminds her that she's not dead. This fits right into the title of the book, as death would be one exit out of life. That's followed by an absurd but terrifying sequence where she's chased by "a giant man-baby", kind of the essence of the male id. That causes her to suddenly turn invisible, allowing her to turn the tables on her attacker. To be sure, turning the tables on the man-baby spoke to the way in which gender was one part of her sense of alienation, but Seitchik soon strips away that layer to explore other layers of self.

Having invisibility doesn't so much trigger a Platonic Ring of Gyges scenario (where turning invisible turns a person into a monster since they will never be caught for what they do) so much as it makes manifest a sense of being erased. She may no longer be a means to an end for the world, but the invisibility doesn't solve her own existential crisis. She takes brief pleasure in being able to go where she wants and do what she wants, as well as watching the lives of others. A sense of loneliness and desperation drives her to actually "live" with other people, including one scene where she starts watching a couple have sex, understands the invasive quality of what she's doing, tells herself she should leave, and stays anyway. It's the point at which she breaks the social contract in a really egregious way, which only sends her further down the road of addiction to other people's lives as a way of not considering her own.

Having invisibility doesn't so much trigger a Platonic Ring of Gyges scenario (where turning invisible turns a person into a monster since they will never be caught for what they do) so much as it makes manifest a sense of being erased. She may no longer be a means to an end for the world, but the invisibility doesn't solve her own existential crisis. She takes brief pleasure in being able to go where she wants and do what she wants, as well as watching the lives of others. A sense of loneliness and desperation drives her to actually "live" with other people, including one scene where she starts watching a couple have sex, understands the invasive quality of what she's doing, tells herself she should leave, and stays anyway. It's the point at which she breaks the social contract in a really egregious way, which only sends her further down the road of addiction to other people's lives as a way of not considering her own.

The turning point in the book is a bit of magical realism where there's a tree growing in her old apartment, with a big knot in the middle. When she reaches in, she pulls out the tarot card The Tower, which means sudden and often destructive change. She then suddenly becomes visible again, but it's revealed that she's shed her skin like a suit and has an opportunity to put it on again. Rather than really revel in this event, she is stuck in the same place she's always been and why she didn't quit her job: it would be the same no matter where she was. If she was a person again instead of a sort of erased being, she'd have to get a job or just hide in her apartment. Any action she might make is equally meaningless, but the offer is rescinded by a talking serpent who angrily crashes through the mirror. The serpent perhaps represented temptation that she denied, an exit she decided to close off. She had come to understand the inauthentic nature of her daily existence and couldn't go back to it.

The turning point in the book is a bit of magical realism where there's a tree growing in her old apartment, with a big knot in the middle. When she reaches in, she pulls out the tarot card The Tower, which means sudden and often destructive change. She then suddenly becomes visible again, but it's revealed that she's shed her skin like a suit and has an opportunity to put it on again. Rather than really revel in this event, she is stuck in the same place she's always been and why she didn't quit her job: it would be the same no matter where she was. If she was a person again instead of a sort of erased being, she'd have to get a job or just hide in her apartment. Any action she might make is equally meaningless, but the offer is rescinded by a talking serpent who angrily crashes through the mirror. The serpent perhaps represented temptation that she denied, an exit she decided to close off. She had come to understand the inauthentic nature of her daily existence and couldn't go back to it.

She tried to go back to her mother's home, only to be threatened with a trip to the hospital. She uses her powers to help a guy out on a train, only to be told by him that his sister had turned invisible and squandered her abilities. Throughout the story, whenever there was a moment when Claire's sanity seemed to be in doubt, Seitchik used a blurring effect. On dream and fantasy pages, Seitchik's crisp rendering was changed to a ragged pencil line, complete with erasures and pencil tracings still evident on the page. That's a technique that Aidan Koch uses as well, and it's sort of a visual version of Heidegger's sous rature: an image that is not quite up to describing the event that is crossed out but still left legible on the page. It's an image that's both there and not there, incapable of fully illustrating an ineffable experience but necessary to provide information and context.

She tried to go back to her mother's home, only to be threatened with a trip to the hospital. She uses her powers to help a guy out on a train, only to be told by him that his sister had turned invisible and squandered her abilities. Throughout the story, whenever there was a moment when Claire's sanity seemed to be in doubt, Seitchik used a blurring effect. On dream and fantasy pages, Seitchik's crisp rendering was changed to a ragged pencil line, complete with erasures and pencil tracings still evident on the page. That's a technique that Aidan Koch uses as well, and it's sort of a visual version of Heidegger's sous rature: an image that is not quite up to describing the event that is crossed out but still left legible on the page. It's an image that's both there and not there, incapable of fully illustrating an ineffable experience but necessary to provide information and context.

A recurring image in the book is that of her phone getting cracked, a reference both to the bad luck that breaking mirrors brings as well as a way of showing a face that's also breaking apart. There are flashbacks to her feeling like she's falling apart from her childhood, which can be construed as a reference to this life-long existential crisis and/or a life spent dealing with mental illness. There are also flashbacks to her best friend, who was her one tether to reality and meaning. When they reconnect over the computer at the end, the fact that her friend is invisible too comes as no surprise. In many ways, the final scenes are the culmination of a giant gag: two invisible people finally finding connection and meaning by staring at each other, perceiving only the background. The existentialist philosopher Gabriel Marcel hurdled the ethics problem with the concept of "communion", which (and often through eye contact and the acknowledgment of eye contact) provided the possibility of perceiving the subjective natures of others. That this moment of communion came even when the two women couldn't see each other is simply a delicious and clever irony. In a way, it makes sense: if perceiving another person as an end unto themself, as someone who is not objectified or classified by one's gaze, then in some ways it's easier to do that without the burden of actual visibility creating a visual that can be objectified!

Seitchik ends the book with an epilogue that at first seems like an implausibly happy ending, creating a projection that seems absurdly happy. Then Seitchik pulls the rug out one last time, fading back into that erasure/blurring technique, noting "it's hard to keep track of invisible people". It's a way of acknowledging that this book is less a narrative and more a series of meaningful episodes that culminate in a single moment of connection. Considering how difficult it is to achieve such a moment in the best of circumstances, Seitchik suggests that the reader should worry less about what might happen next and instead spend more time thinking about what just happened. That final scene finally saw Claire stop looking for exits and be in the moment with another, just for a moment. The beautiful simplicity and utility of her line provides a a crucial deadpan quality to the book, giving the more striking and experimental visual flourishes that much more power.