The following is an excerpt from We Told You So: Comics as Art, the long-awaited oral history of Fantagraphics Books put together by Tom Spurgeon with Michael Dean. This particular section covers the late '70s to mid-'80s, when the company was headquartered in a three-story house in Connecticut, and began publishing comics as well as criticism. Watch out for appearances by Gary Groth, Kim Thompson, the Hernandez brothers, Peter Bagge, Jack Jackson, Gil Kane, Art Spiegelman, Heidi MacDonald, R. Fiore, Bud Plant, R.C. Harvey, and Carter Scholz.

NEW DIGS

Gary Groth: I don’t remember our move to Connecticut feeling that momentous. Everything seemed impermanent to me back then. The company could have gone out of business two months after we moved to Connecticut; I would’ve just moved on.

Kim Thompson: You have to bear in mind that never in my life up until that point had I lived more than three years in the same house, let alone city, let alone country. So moving to Connecticut was a smaller leap than anything that had come before.

Rick Marschall, comics historian and Nemo editor: I flattered myself at the time to think that I played a role, or planted a seed, regarding the move to Connecticut. I met Gary, Mike and Kim after I started at Marvel, and I had just moved to Westport for the second time. I remember urging a Connecticut World HQ for Fantagraphics on Gary as a matter of inevitability and pride. Comic-books artists in the stretch between Greenwich and Ridgefield included Gil Kane, Curt Swan, John Byrne. When I later moved from my apartment in Westport to a house in Weston, Bill Sienkiewicz took the apartment; Terry Austin then rented upstairs. Anyway, I have a recollection of urging Fantagraphics’ move to Connecticut for all these reasons — and of course proximity to New York City — and my memory is that Gary said “Connecticut?” in the same way Ralphie asks Santa in A Christmas Story, “Football? What’s a football?”

Groth: I knew nothing about Connecticut, had never set foot in the state before. But, New York was too expensive (although I don’t know if Brooklyn was more expensive than Connecticut at the time) and Connecticut sounded like the kind of place we could rent a house rather than an apartment.

Thompson: The move to Connecticut was a pretty big deal in one way: At that point we both quit our day jobs. I was a general office worker. Gary was doing freelance typesetting. He didn’t so much quit a job as stopped doing it. At that point we realized we had to do this as a full-time job or not do it.

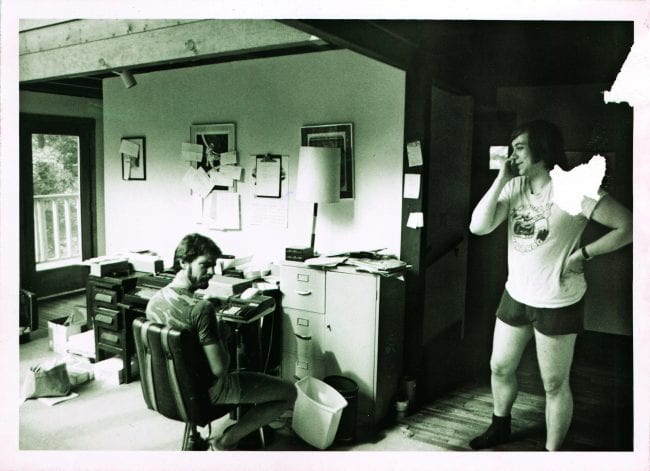

Groth: When we got to Connecticut, we rented a house. It was only the two of us at the beginning. We worked in a basement in the house for about a year, but the basement flooded at least once, causing havoc with comics, files, everything on the floor (which was everything). So, we moved to this huge three-story house, in an exclusive section of Stamford. Everybody thought I was nuts, since I was the one who engineered this move, but I thought we needed more space and I thought it was something of a deal. It had five bedrooms, two living rooms, three sundecks, a ground-level “basement” that wouldn’t flood, a two-car garage. It was in this area surrounded by other huge houses, owned by TV-network executives and doctors and lawyers. We clearly didn’t belong there.

Dwight Decker, editor: Some people called it the Ski Lodge because it somewhat resembled one, built into a hillside so the second-floor back door was at ground level while the first floor/basement had a front door. It was well back from the street and pretty well surrounded by woods. There were other houses in the area, and I wonder if there was a potential conflict with zoning laws since Gary was running a business out of his house and there were UPS and other delivery trucks making frequent stops.

Kenneth Smith, cartoonist and writer: Every closet and shelf-system was crammed with reference copies and Fantagraphics publications. The living room was rather shadowy and very amiably laid out, nearly a conversation pit. It must have been a fun place to work, even with hell-on-wheels deadlines over everybody’s heads. In retrospect, I guess I wonder why there weren’t more tables and working surfaces. I know I always have a shortage of unencumbered surfaces, not to mention shelving.

Thompson: It was the same thing, different place. We just lived in a nicer house.

Steven Ringgenberg, editor: It was in a beautiful neighborhood and I liked to go running when I lived there.

Groth: We shared a really long driveway with one other house. Five of us lived in the house. The office was on the ground floor in a large wide-open space, which included a bedroom and a sauna. Yes, a working sauna! The living rooms and the kitchen and two bedrooms were on the second floor and on the third floor were two more bedrooms. Our neighbors put up with us for six years. I don’t know if they knew quite what we did. I think they probably thought it was some drug-dealing operation, and the fewer questions asked the better.

Decker: Because housing was so expensive in Stamford, Gary sublet bedrooms to a couple of people who had nothing to do with Fantagraphics and worked elsewhere (I can’t remember if it was more than one). I can only guess what they thought of the mad goings-on.

Tom Heintjes, Comics Journal news writer: As the new guy, I got the crummiest accommodation. It was a storage room where they kept boxes of back issues. I stacked the boxes up and laid a mattress on top of the boxes. I had enough room to sidle out and then sidle back in at the end of the day. All I ever did was work and sleep.

Mike Catron: It was a very nice house. It had paper walls, kind of a Japanese design. The upstairs main bedroom where Gary was had a huge sliding door with paper panes. Down in the basement, they had a sauna. It was a redwood booth, with a pile of coals, you’d turn on the electricity and you could get a sauna bath. That lasted until we needed more space and it became a storage area for something or other. Kim was fond of going down there in his little towel and taking a sauna.

Decker: Most of the work was done in the finished basement, which had a drawing table for paste-ups, a typesetting machine and a couple of desks. Somewhere in the rear was a small room where the back-issue stock was stored. Kim had a back bedroom, I seem to recall, but exactly where it was and if I was ever even in there, I’m not sure now. Gary had the master bedroom on what amounted to the third floor, facing a balcony that looked out over the living room. Hours were very irregular, with all-nighters being frequent. Gary in particular had shifted his schedule to the point that he almost never emerged before noon, and he had to struggle if he had a morning appointment in New York City.

Groth: Ernie Bushmiller lived in the house next to the beginning of our driveway. We could see his house from the balcony. I didn’t give a shit about Ernie Bushmiller at the time so I never even knocked on his door. But I remember passing his mailbox every day with his name on it.

THE FIRST EMPLOYEE: PRESTON “PEPPY” WHITE

Thompson: The first person we hired when we got to the new house was Peppy White. We hired him on to do production work. We were tired of doing it all ourselves.

Groth: Peppy moved to Connecticut from Virginia. He was a pal of mine from Virginia. We were expanding and needed another hand.

Preston “Peppy” White: I moved to Stamford, Connecticut, when I was about 20. Having been friends with Gary since I was 14, and having similar interests in publishing and comics, I guess I was a logical choice to be the first employee.

Thompson: Hiring Peppy also marked the beginning of the period where the Fantagraphics staff was a bunch of our buddies working in the Fantagraphics commune. Tom Mason, a friend of a friend, was hired soon thereafter to supplement the production staff.

Peppy was a great kid. He looked up to Gary. At that time he was three or four years younger than Gary. The distance between 22 and 18, that’s a lot more than between 50 and 46. We got along great.

Heintjes: Peppy was a real character. He was a very high-strung, very energetic, very funny, very cutting and very witty guy. He was older than me. When I came there in my early 20s, he was in his mid-20s. He seemed experienced and worldly.

I always admired Peppy, because he was an art director on a lot of key, early projects.

Thompson: Peppy worked his ass off and was a really sweet guy. He was also kind of a goofball and accident-prone. I still remember the eerie calm in his voice when, in the middle of trimming sheets of cardboard with an X-Acto knife, he said, “Guys … I need someone to take me to the hospital. I just cut off the tip of my finger.”

Groth: He cut the tip of his finger off once with an X-Acto blade. I was about to take him to the hospital and thought I should grab the damned thing to take with us. I looked around for it on the floor and couldn’t find it! Then I noticed my dog, Plato, slinking off. Ooops.

Heidi MacDonald, writer: They once tried to set me up on a blind date with Peppy White. There’s a deep, dark secret for you.

Thompson: He would get into the most bizarre scrapes with girlfriends, other people, the law and household objects. These occurrences became known as “Pep stories,” and would get told and re-told, often by Peppy himself.

GIL KANE’S FRIENDSHIP

Groth: I spoke to him on the phone once or twice to set it up, but I really met Gil Kane for the first time when I interviewed him for the Journal at a Boston convention. Subsequently, I spoke to him on the phone often. We would have these marathon conversations. In the beginning, I don’t really think he knew who the fuck I was. I would call him, say, “Hello, Mr. Kane,” and he’d be off and running. I would occasionally interject a remark and set him off in another direction. He was so voluble that it was as if he hadn’t talked to anybody else between our phone calls and had to make up for it talking to me. At first I think he just enjoyed talking and I enjoyed listening, so it worked. When I moved to Connecticut, I called him up and we got together.

Thompson: Gary and Gil Kane knew each other before we came to Connecticut. There was a big Kane interview in Comics Journal #38. That interview cemented the beginning of their friendship. Certainly by that time, they were thick as thieves. Gil was a real father figure to him, and they had a warm personal relationship.

Elaine Kane, Gil Kane’s widow: We lived in Wilton [Connecticut] and they lived in Stamford. They became really good friends. Gary would come to the house. We would go to their place in Stamford; they had big parties and everything. It was an interesting relationship. They were both very intelligent. The conversations were interesting. A lot of time was spent later on with Burne Hogarth as part of the group.

Gil enjoyed Gary and his — how can I put it? — not his odd behavior, but his against-the-grain behavior. Gary did pretty much what he wanted. Gary would come over and we would go to dinner and Gary would be wearing a shirt that said, “Fuck” on it. We would meet people and Gil with a straight face would introduce them and we could see the horror on their faces.

White: Once I went out to dinner with Gary, Gil and Burne Hogarth. Gil and Burne spent the whole night arguing with each other. Gary and I could only sit back and watch these two titans verbally wail away at each other about this point or that point as if the fate of the intellectual universe hung in the balance. Burne would be yelling and pounding the table and Gil would wave his hand in the air dismissively and say, “No, but you see, my boy … ”

We took a drive up to Gil’s house in Connecticut and surprised him on his birthday. He was really touched and had no idea we were going to do that. He had the biggest grin I’ve ever seen. We all had screwdrivers sitting in his studio.

Groth: I enjoyed how outspoken Gil was. Most artists of his generation had this unspoken but strictly adhered-to policy of never speaking candidly about their fellow professionals. Gil was willing to criticize publishers, people who wrote his paycheck, and that was enormously attractive to me. I told him once, when I was still in Maryland, that he reminded me of Gore Vidal, who was literally a year older than Gil, with, at that time, the same silver-colored hair, and the same aristocratic bearing. But, he replied that he felt more like Norman Mailer. Mailer was my height and bellicose. I didn’t get it at the time. He explained it to me and it made sense — Gil always felt like the odd man out in comics. Vidal was critical of entrenched power, but he was part of an elite social circle whereas Mailer was always viewed by his peers with skepticism if not outright hostility and occasionally a grudging admiration — just like Gil. So, I was only looking at surfaces when I made the analogy, and Gil was exactly right on a deeper level. Even though he achieved a certain literary respectability, Mailer acted like an outsider.

Elaine Kane: They respected each other. They would tweak each other about the business. There was a lot of trust there, too. They trusted each other. They were both great readers; they would read different things and discuss them. It was an interesting time. A very interesting time. They became very good friends based on mutual respect.

Groth: If you’re lucky, you’ll meet a handful of people throughout your life with whom you click. Gil and I clicked on a profound level. We shared so many of the same enthusiasms and admirations and passions. It’s such a pleasure to be with someone with whose values you’re so in synch. And so rare in the context! At that point, in 1979, 1980, we were roughly the only two people in the comics profession who shared these values. Or so it seemed. That would change and change quickly as The Comics Journal gained steam and more and more people who shared those values wrote for it, and more artists joined our cause. But early on, it felt like the two of us against the world.

Gil Kane, “An Interview with Gil Kane,” The Comics Journal #38 February 1977:

The thing in comics are the pictures, the images. Comics are totally a visual form at this point. Its entire appeal is in the emotional impact of those images, of those fantastic images — on the eye and the mind. And they make deep connections, deep emotional connections that keep people rooted to this material long past the time that they’ve gotten tired of the last repetitious comic book.

Groth: He really was a provocateur and attracted genuine animosity from his peers; he wasn’t just putting on an act, he was the real thing, he believed what he said. He was smart, and thoughtful and had theories about cartoonists, all of which made sense to me. He was the only guy in mainstream comics with his brains and ambition who wasn’t living up to them. We talked about it endlessly.

CLICKING WITH ART SPIEGELMAN AND FRANÇOISE MOULY

Art Spiegelman, cartoonist: I can’t remember when I met Gary. This is the problem of being a memoirist with Alzheimer’s.

Spiegelman: I remember Larry Hama. I don’t remember arguing with him, but I guess I’m an argumentative type, so I guess it could have happened.

Groth: I could be wrong about the trajectory of the conversation, but Art must’ve known of this shitty comic Hama was editing, was clearly offended by it and told Hama exactly how he felt. And I remembered being impressed because Art was not pussyfooting around, he was telling him he was pushing a fascistic point of view, which is what I thought as well. It was a memorable confrontation, and you don’t see too many of those at comics parties. I remember being impressed and admiring Art, his willingness to confront someone like that.

Thompson: We knew about Spiegelman. Breakdowns had come out. We knew about Arcade, we knew about that material. We knew about the original Maus, “Prisoner on the Hell Planet” and all of that.

Groth: Art wasn’t a prodigious cartoonist. I was familiar with the major underground cartoonists, but I wasn’t familiar with Spiegelman. I had read a few of his things but couldn’t place the name. Kim knew either of him, or Kim might have met him on one of his trips to New York.

Thompson: Spiegelman was a fairly early major interview. As I recall, it was issue #65, and in fact when we first started talking to Art, he was working on the first issue of Raw. The first part of the interview was done before the first issue of Raw came out. The second part was after they had done the first issue of Raw and they were working on the second issue.

Spiegelman: I was aware of them; I don’t know what happened when exactly. We were monitoring what they were up to. It was all part of, at that time, a small market for weird material.

Thompson: As you might imagine, Gary and I and Art and Françoise clicked very much. Raw Books was a complete inspiration.

Spiegelman: We knew what we wanted to do very early on. It overlapped what was happening in comics. But it wasn’t of it. In some way it still isn’t. I feel somehow in the center of the mix and to the side of it. Even at a point where a lot of people we introduced in Raw are being published by Fantagraphics, I’m still bumbling to the side somehow.

Groth: I liked Art and Françoise, but I don’t think they were an inspiration to me, at least not in terms of publishing. Raw was sui generis and wasn’t really a model for anything I felt we were capable of doing. What I found inspirational about Art was his infectious enthusiasm for greater sophistication in comics. He was always discovering new (or old) cartooning talent. One of the major virtues of Raw was all the European artists it brought to my attention. Every time I would drop by Art’s place in Soho, he’d drag out various artists’ work that he had on hand for the next issue of Raw and proudly display and explicate it. His enthusiasm was absolutely infectious.

Spiegelman: It wasn’t just European comics. It was trying to find a place to stand as the underground comix tide lapped back out towards the horizons. There were a number of interesting cartoonists with no place to go. A good case in point was Charles Burns, who has certainly come into his own in the years since. But when we first met him, we were trying to shoo him away. When Charles showed up at our door after seeing the first or second or both Raws, we were trying to shoo him away since people were ringing our bell every so often because we lived and worked in the same place. We asked him, “Whoever you are, send stuff.” And then when he sent stuff, it was like “Please come back.”

He told us the stories of trying to get published in underground comix. That just seemed mind-blowing to me. It was proof that there was a need for this weird thing we were doing. That Denis Kitchen had no place for him, for example. Certain artists from the Arcade days still needed a home, because they couldn’t find one. Mark Beyer comes to mind as a good example of that. People I was teaching when I was teaching at SVA had no place to go, Drew Friedman and Mark Newgarden and Kaz being examples of that. There wasn’t any construct for any of these things in the 1980s. Anything that was even close became something we’d look over. Our aesthetic and Wendy Pini’s was very different, but Elfquest started at the same time, and we became very aware of that. Similarly with Gary, when he began publishing Lloyd Llewellyn and the Hernandez Brothers, it was interesting. If anything, it took me longer to recognize those artists because it was closer to my ideal of what a mainstream should be.

Groth: We weren’t publishing comics when we befriended Art; we were just publishing The Comics Journal. That was our connection: He was reinvigorating comics and publishing the kinds of comics we wanted to see and we were publishing a critical magazine that could write about them.

Thompson: We admired the literary graphic ambition. The enormous care they took with production. The integration of international work, which was certainly unique to them. They represented everything we wanted to see in comics.

Spiegelman: We had great conversations about comics from the get-go. That I do remember.

PUBLISHING COMICS

Thompson: Money was always a problem. When funds would run low, we’d try to think of some way out. We had to figure out things that would make us a ton of money. That was the time we did the X-Men Companions, a Focus on: George Perez, a Focus on: John Byrne, an Elfquest companion as well. For all the hostility between us and Marvel and us and DC, they were remarkably accommodating with something like the X-Men Companion. They even shot a shitload of photostats of X-Men pages for us. There was an old idea that fanzines could print as much as they wanted, and it would serve as promotion. It was a little dicier doing a whole book, but they were perfectly amenable to it.

Groth: I cut a deal with Jim Shooter, who gave us carte blanche to use all the X-Men images we wanted to for the X-Men Companion. They even supplied black-and-white stats for us. My gut told me that there was a sort of quid pro quo implied, that we would be nice to Marvel in The Comics Journal as a result of this largesse. I chose to ignore that implication, of course.

Groth: I cut a deal with Jim Shooter, who gave us carte blanche to use all the X-Men images we wanted to for the X-Men Companion. They even supplied black-and-white stats for us. My gut told me that there was a sort of quid pro quo implied, that we would be nice to Marvel in The Comics Journal as a result of this largesse. I chose to ignore that implication, of course.

Thompson: At that point, we’d also started publishing Amazing Heroes, which took a bit of the edge off our relationship with Marvel and DC. Not only were we publishing a magazine that was friendlier to them, but because of AH, The Comics Journal started focusing less and less on mainstream comics, which means we pissed them off less.

Heintjes: Gary offered me the princely sum of $12,000 a year, which is $12,000 more than I ever made in my life. I thought this was great.

Thompson: We never gave ourselves any money. Gary and I had to give ourselves minimal salaries. I didn’t get any salary for years. I was essentially unemployed. I still get those annual Social Security statements that list your annual salary all the way back to when you were 20 and there’s about five years when it’s literally zero, and then it moves up to $2,500 or something and finally cracks five figures years later. We didn’t buy much. We needed money for gas and food, movies and maybe a couple of books. Temptation only occurs when there’s a period when you’re flush, so that was never an issue with us. We usually had nice houses, but we had a bunch of people living there. In Connecticut we had a gorgeous house. But he lived there, I lived there, we sublet a room, the office was there and so on. There was no money to piss away, though.

Groth: We weren’t set up to publish comics, per se, but back then things were so loose. We had the distribution channels in the growing comics-shop market, and by that time there was Phil Seuling’s Seagate Distributors and Bud Plant and a couple of smaller distributors. We were probably dealing with four or five distributors. There may have been a shitload of them, but they were all pretty minuscule. We had the infrastructure and this inchoate distribution system locked in because of the Journal.

Thompson: Publishing was a logical thing. Gary had already done it. He’d done it with a magazine called Always Comes Twilight. That was more of a graphics thing, less comics, but there were a couple of short comics in it. That was in the late Fantastic Fanzine days. We were also publishing comics in The Comics Journal. We were reprinting the Howard the Duck and Spider-Man newspaper strips. And I think at that point we were publishing some short comics by Grass Green. We ran a few episodes of this utterly weird medieval comic by Don Rosa, years before he became the new Carl Barks.

Groth: Always Comes Twilight was basically a hold-over from my fanzine days, eventually published in 1976, a few months before we started the Journal, but full of the artists I published in my fanzine. I don’t remember why it took so long to publish or even how I managed to do it at that time.

Don Rosa, cartoonist: I don’t recall how the comic strip that I did for Comics Journal #41 came about ... But I recall why I did that strip, especially since it was nothing like the comedy-adventure sort of stuff I’d always done. By 1977 I was living in an apartment, eating meals at nearby restaurants and eventually struck up a friendship with a waitress in a nearby Denny’s. I soon learned that she had a slight drug problem, but was very interested in fantasy “sword and sorcery” writing. I thought if she wrote a story for me to illustrate that might help her self-respect or something, anything to get her off needing the drugs.

Thompson: The Flames of Gyro by Jay Disbrow was the first original comic book we did. Disbrow, Hugo, Los Tejanos and Don Rosa’s Comics and Stories — they happened really close to one another. It’s all a blur.

Groth: I may have met Jay at a convention and I don’t remember if he offered to do a comic for us or if I asked him if he would; the former seems more likely. I thought it would be fun to publish an old school Golden Age artist who had dropped out of the field and wanted to come back.

Jay Disbrow, cartoonist: Gary Groth, he must be in his 70s by now. Is he still publishing? I met Gary Groth at a convention. He remembered my comics for Star Publications. He let me do whatever I wanted, which was science fiction. The comic was called The Flames of Gyro.

Groth: We had a very extensive correspondence beginning in the end of 1978 about The Flames of Gyro. There was a lot of back and forth about this and other projects he pitched. He drew the book on these enormous, two-and-a-half-by-three-feet sheets of paper. Each page was as big as my desk. I’d never seen original art this size before. They stopped drawing them that big around 1952 or so.

Thompson: It was literally, “he was there and he had the book.” He said we could publish it and we said, “Sure!”

Groth: He drove the original art up and left them with us. Flames of Gyro was this goofy Flash Gordon-type science-fiction/fantasy thing. I shouldn’t say “goofy,” because it was dead serious, but that made it even goofier. It had this weird labored beauty to it, because it was drawn in a meticulous wash. That made it a production challenge because it had lettering and wash on the same page, so we had to double-burn it to make the wash reproduce in halftone while the lettering would retain its 100-percent black ink. I remember enjoying it as a learning experience.

Marschall: I was driving somewhere with my wife and kids — maybe to start a vacation — and I stopped in for some reason. Gary and Kim could not wait to show me the artwork that had just arrived. These usually quiet and invariably cynical guys were breathless, watching for my reaction as I looked at each page. I honestly thought they were putting me on. I mean: Disbrow, nice, old-school gentleman and all that; but I really thought it was the craziest junk I ever saw. Gary and Kim were serious; I mumbled some niceties and drove the hell out of there.

Groth: We thought it would be an interesting experiment, to see if we could publish a comic. Jay himself was such an ingenuous guy, a sweetheart, much older than us, though younger than I am now, I think. He had grown up in the very commercial environment of comics, so he was a real professional grown-up but also had a childlike enthusiasm for this work. He drove a big American car — something like an Impala — and smoked a pipe and wore a suit. He was like my dad (except for the pipe). I can’t explain why we published it, really, except we thought it would be fun and we genuinely liked Jay.

Disbrow: I used to work for L.B. Cole and I wrote my own material. But I hadn’t worked in comics on a full-time basis since the big crash of 1954. 80 percent of comics publishers folded after that due to the infamous Dr. Wertham and a congressional subcommittee investigation connecting juvenile delinquency to comics. Only the giant publishers survived that.

I had to go into commercial illustration, which paid more, but it wasn’t the same. With the comics, you have a romantic element, mystery and drama. I knew from the time I was 14 that was what I wanted to do.

Thompson: How many did we print? I don’t know. Maybe 2,000.

Disbrow: I don’t think it sold very well, because it was a one-time thing. We didn’t do any more. It wasn’t competitive, because it was black-and-white. I’m sure it would have done much better if it had been in color.

Groth: We had copies of The Flames of Gyro for years. It filled our garage. We must’ve printed 10,000 copies. Finally, right before we moved to L.A., I asked Jay if he wanted to pick some up, free. He drove up in this gigantic car — a Caddie or a Buick or something. And we just kept loading the car up, filling the trunk, the back seat, every available space that wouldn’t be occupied by he and his wife, and Jay kept saying, “That’s enough,” and I’d say, “Just another few boxes, Jay.” We didn’t want to haul those damned things to California.

Ad copy for The Flames of Gryo, 1979:

What unholy power throbs within this medallion … that drives men to kill for it … and die for it!? This man knows its secret and has sworn to destroy it … but this man wants it — at any cost! From the freezing void of space … to the raging hellfire of a remote world … theirs is an epic conflict which can only end in death!

Disbrow: After The Flames of Gyro, I did a little bit more in comics and I went to the conventions. I did six years of a strip for the Internet called Aroc of Zenith, 312 pages, but I’m retired now.

Groth: Jay was drawing a sequel to The Flames of Gyro, but, uh, we didn’t publish that.

Bud Plant: I don’t think that sold very well. Maybe it’s time to pull those puppies back out. I thought he was a funky artist back then, but I kind of like a lot of those guys now.

(continued on next page)