Justin Green died in the early hours of Saturday, April 23 at Hospice of Cincinnati. The cause of death was colon cancer, according to his wife Carol Tyler. Green had a tumor removed a year and a half earlier, but the cancer came back aggressively. He had refused chemotherapy because his doctor told him that the chemo could cause loss of sensation in his fingers, and he wanted to write, draw, and play his guitar, said Tyler. “He had so many ideas. I loved and admired him so much. It was heartbreaking to see him struggling at the end. He convinced himself that by becoming a vegan, taking herbal supplements, and taking other mystical routes, he’d beat it.” Green was 76 years old.

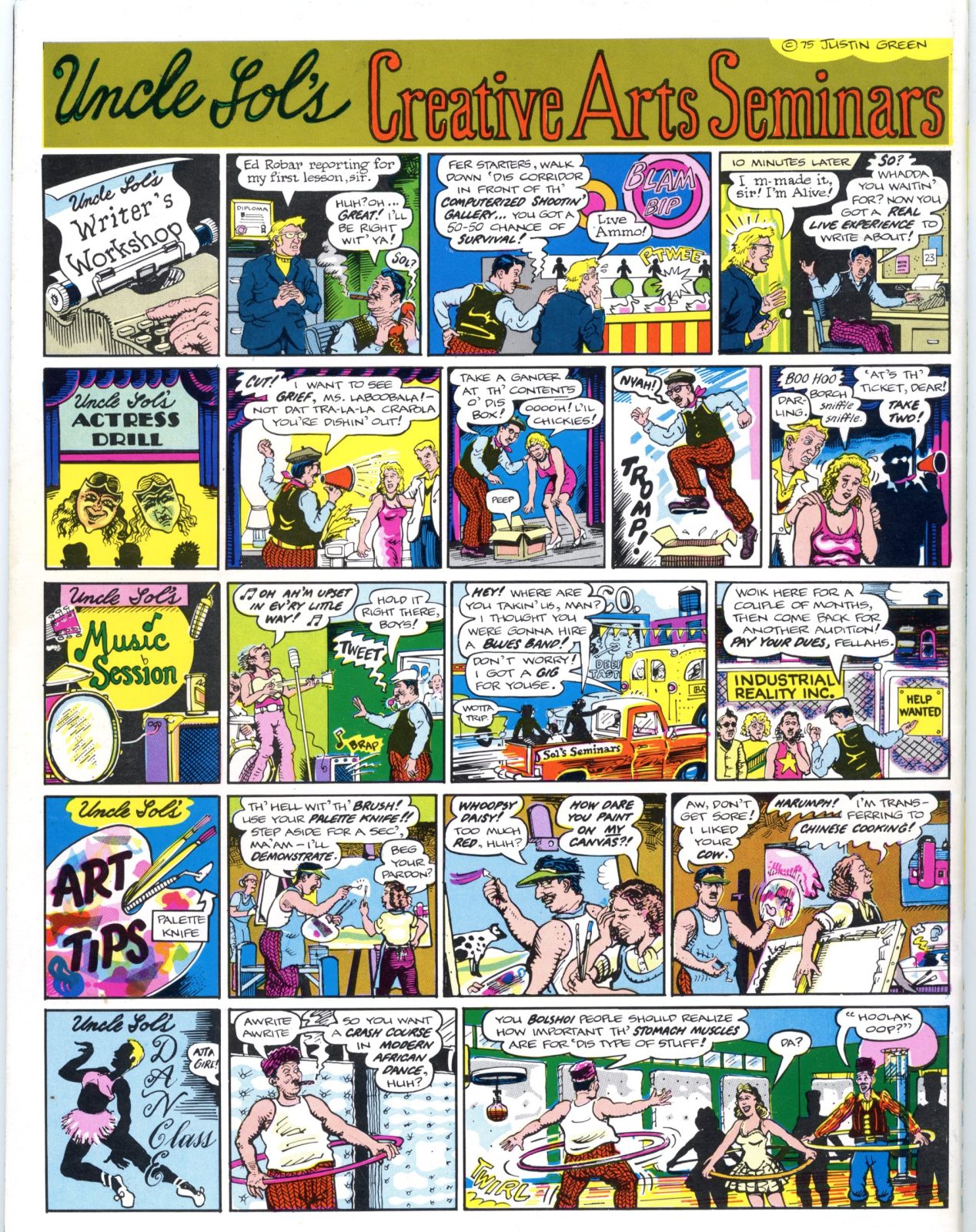

A very private person and a modest artist, Green made his living primarily as a sign painter for the past several decades. He was one of the original cartoonists of the underground movement that changed comics forever in the 1960s and 1970s. He and his colleagues, who included S. Clay Wilson, Robert Crumb, Bill Griffith, Art Spiegelman, Jay Lynch, and many others, rejected the overground genres of superheroes, funny animals, romance, and science fiction with more radical adult themes and unusual subject matter, breaking free of the restrictive Comics Code Authority that regulated the comic industry. Primarily located in the San Francisco Bay Area, where Zap Comix #1 spontaneously appeared in 1968, they formed a cadre of dedicated comic book artists and publishers who worked completely outside of the established New York based industry that dominated the medium for more than forty years.

Green described the workings of underground comix art in 1973. “It was a loose community of artists devoted to revitalizing a humble art form, though not all spirits were kindred. Like any movement, there were cliques and warring factions, but all held to the ideal of reaching a common audience while reinventing the formal boundaries that had defined the medium. Like any utopian experiment, ideals were challenged and rewritten in the face of the daily grind. It was a harsh life lesson for me, but there were lots of laughs and some beautiful times, too.”

In addition to the accomplishments of his peers, Green broke fertile ground in the field of autobiographical comics. In 1972 he produced his most iconic piece of work that would define him for the rest of his life, Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary. There would be several new editions published over the years, including a deluxe oversized facsimile edition by McSweeney’s Books in 2009.

Binky Brown represented both aberration and evolution. It defied the traditions of a medium in which most cartoonists created fictional characters and stories, sometimes based on their actual experiences, but always at a remove. Green challenged those cultural conventions with Binky Brown. He was the first to openly render his personal demons and emotional conflicts within the confines of a comic. Green spoke through a semi-fictional character named Brown, but this alter ego was as close to the bone as he could cut it. His compulsive habits and shameful moments take center stage in this theater of cruelty. Gags and plot lines play second banana, and props become weird fetish objects that transmit the artist’s anxiety. The work was created out of internal necessity, he insisted. Binky Brown’s tortured tale begins with the accidental destruction of a religious icon and ends with the deliberate destruction of many of them. In between, Green takes us on a tour of young Binky’s psychosexual development in a post-war middle class Midwestern suburb. He didn’t waste any time building up his ego or making himself look heroic. A girl he likes calls him an icky spaz. Two third graders smash a cupcake on his head. He soils his shorts. He has homosexual thoughts about Christ, but through all his trials and tribulations he also manages to wrench loose a few yuks.

“I saw very early in the book that I would have to sacrifice the absolute journalistic truthfulness of some of these in order to weave a story,” said Green. “Virtually every incident in the book is allegorical, even though some have a closer foothold. I’ll give you an example. I really did bang my head into the headboard every night. I probably did permanent brain damage. But on the other hand, I never had my ass kicked by two third graders. But they both seem to fit. They’re both allegories in a sense because they are meant to suggest or convey a whole generalized idea about some subjective feeling, such as order or fear or guilt.”

The first ripple effects of this tour de force immediately spread to his contemporaries in the underground. Robert Crumb likewise laid bare his id in “The Confessions of R. Crumb” for The People’s Comics in that same year, and again with “The Adventures of R. Crumb Himself” for Tales of the Leather Nun the following year. So did Art Spiegelman, who began his family’s “Maus” saga in Funny Aminals (1972) and chronicled his mother’s suicide in “Prisoner on the Hell Planet” in Short Order Comix #1 (1973). It didn’t take long before many more artists came to believe that their own foibles were fair fodder for funnies and personal comics quickly proliferated.

“I’ll never forget seeing the unpublished pages of Binky Brown hanging from a clothesline stretched around the drawing table and all through his living room back in 1971 and knowing I was seeing something new get born,” wrote Spiegelman in an introduction the Binky Brown Reader.

Like an acorn that grows into a great oak, Green’s groundbreaking book yielded a bumper crop in subsequent generations of cartoonists who were similarly compelled to tell their own stories. Legions of practitioners all around the world have crafted a wide variety of autobiographical comics ranging from lurid confessions, intimate diaries, travelogues, braggadocio, family histories, crimes and misdemeanors, participatory journalism, exorcisms, and secret desires, as well as the trials and tribulations of the daily grind.

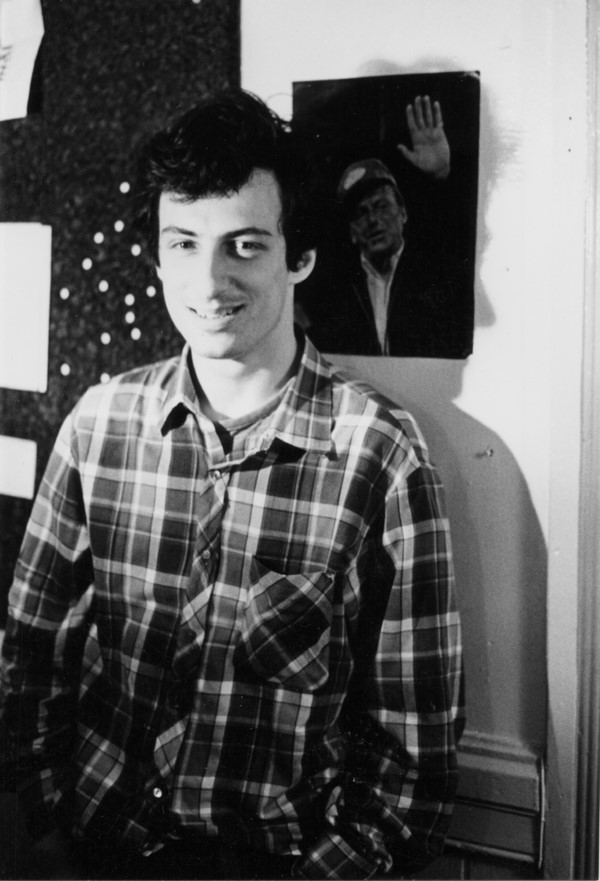

Justin Green was born in Boston, Massachusetts on July 27, 1945. In the sixth grade he created a magazine called Step-Up with an older friend, Ricky Schwartz, which consisted of “derivative ironies gleaned from early Mad and Panic,” said Green. “I also did posters for school functions, which I agonized over. I excelled at seasonal type cartoons, which were done in a less self-conscious way.” His interest in humorous material diminished during high school when he began attending life-drawing classes in downtown Chicago. In 1963 he entered the Rhode Island School of Design, and the following year he took classes at the Art Institute of Chicago. In 1967 he applied for the European Study Program and spent a year in Rome, Italy. It was there that he saw his most inspirational piece of art, an underground newspaper that reproduced a comic called “Itsy and Bitsy” by an artist named Robert Crumb.

“The page was packed with harsh drawing, stuffed into crookedly drawn panels. I was engrossed, even before reading, in the texture of the page. The drawing was disarmingly simple and consistent yet had none of the spineless minimal look that characterizes so much contemporary cartooning. In fact, the piece reminded me of the harsh, gothic image of a woodcut. Exploding in frenzied laughter, and pounding the wall like a mad man, I knew I was on to something. I hadn’t seen anything that grabbed me as much since Harvey Kurtzman’s Mad was on the stands in the early ‘50s, not even the Pieta in front of me. So, I started to think about the things that had formed my own aesthetic, which were, of course, television, movies, and comic books. I’d always been kind of ashamed of that and felt that I had to look to other cultures and other eras for inspiration, but something happened when I saw that Crumb piece. It was a call to arms for me. I immediately started cartooning again; something I had done only in secret since high school.”

Justin Green landed a job as a teaching assistant at Syracuse University for the 1968-69 school year. As he taught undergraduate classes and painted, comic elements continued to dominate his compositions. He was trying to be a cartoonist, but he was going about it the hard way, said Green. “I began to refine the tools that I needed and to disown the ones I didn’t need, and my work started getting clearer and simpler, which is a cartoon language. You do things for reproduction, not for the original. The more that I worked, the more my methods got streamlined, and I saw that I wouldn’t have to cut each panel up and paste it on a board later. I used to do that. Can you imagine that much work on every panel?”

He sent the underground tabloid Yellow Dog a strip called “The Dip”, which was set at Riverview Park, an amusement park in Chicago, and to his surprise, editor Don Schenker accepted it. Then he drew “A Temporary Relapse”. A ventriloquist, in a fit of jealousy, sets fire to the puppet of a woman on his own hand. Barely escaping injury, he then gives himself a fire safety puppet show.

In 1969 Green moved to New Jersey, just across the Hudson River from New York City, where he met several other cartoonists being published in another underground tabloid, Gothic Blimp Works, and joined their ranks. “I knew my work was crude,” he admitted. “What reassured me was that the people I was publishing with were crude, too. I could see it. Even in the early Yellow Dogs, there were a lot of people just like me, who were unpolished but had something to say.” Green broke into the Gothic Blimp Works in the third issue with a one-page story about a strip show he saw when he was sixteen. “Then the Mad Peck started to promote me to the Providence Extra, much to the consternation of the editors there.”

“By late ‘68, everyone personally knew of somebody who had been killed or maimed in the Vietnam War,” he said. “When the draft lottery went into effect, I drew a number in the high 200s. Shortly afterwards, I took a one-way flight to San Francisco, the Mecca of underground comics. Rents were still cheap, and a lid of decent weed went for $25, the going page rate. Anthologies were born daily, and in those pre-glut days, there was a ready audience for each title. It was possible to live on seven ten-hour days a week. In exchange for the slave labor, we who comprised the United Cartoon Workers of America got total artistic freedom to unleash our graven fantasies on the counterculture.”

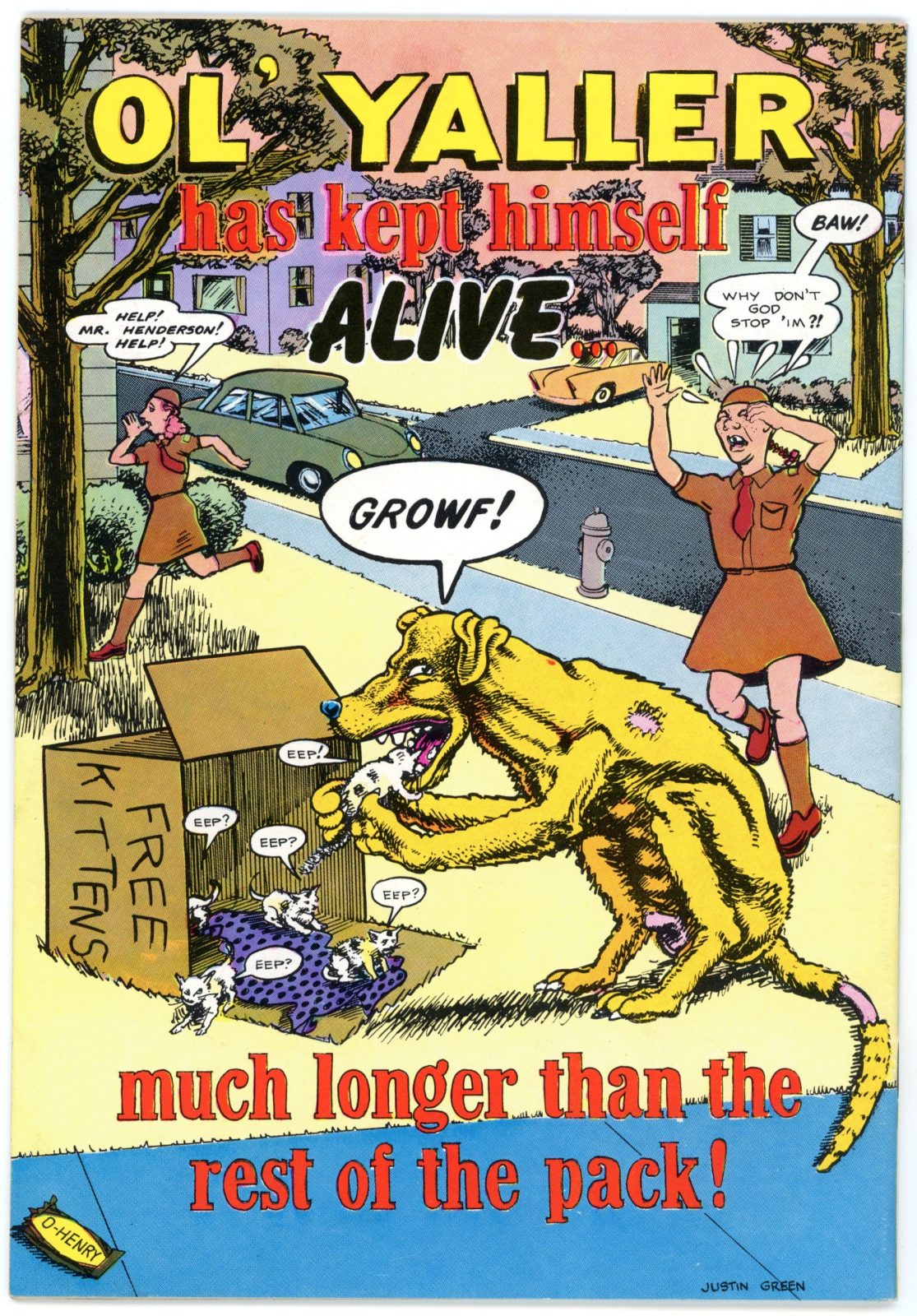

His solo comic work included Sacred and Profane, Show + Tell Comics, and Justin Green’s Spare Comic, which initiated the mini-comic genre, along with "Jud" Green’s Underground Cartooning Course. He also contributed strips to Arcade, the Comics Revue, Bijou Funnies, Comix Book, Insect Fear, Laugh in the Dark, Raw, Tales of Sex and Death, San Francisco Comic Book, Snarf, Two Fools, Weirdo, and Young Lust.

The underground comix movement peaked with the publication of Arcade magazine in the mid 1970s and Green switched careers to commercial sign painting. He continued to draw two regular comic strips, “Musical Legends of America” for Pulse, the magazine of the Tower Records/Video chain, and “Sign Game” for the trade journal Signs of the Times. He also appeared in Print, National Lampoon, Apple Pie, Harpoon, Heavy Metal, the New Yorker, and the Sacramento Bee. “I helped Jim Woodring with scripts for 'Jabba the Hut' and an 'Aliens' series for Dark Horse Comics,” he said in 1999. “I continue to work in oil and watercolor. I am a singer/songwriter and a guitarist.”

Filmmaker John Kinhart has been at work on a documentary about Justin Green and Carol Tyler for several years, called Married to Comics, which is a biography of their relationship. He expects to release in 2023. “Justin was a giant in the field of comics,” said Kinhart. “He was thoughtful and impressive, one of the most important people I met in my life. In getting to know him, he was not what I expected. Most of all he wanted to be a recluse.”

Their marriage was “wonderfully nutty,” said Carol Tyler. “The guy has been impossible. I gave him the latitude to do whatever he wanted to do, but he made everything much more complicated than it needed to be.” They lived in a duplex in Cincinnati, she upstairs and he downstairs, “for my sanity,” she said. “Before the cancer, we had the most fun out at our farm in Kentucky during the summer. We had plans to turn the ‘Ink Farm’ into a comics workshop and retreat place. But then cancer and corona - it was beyond disappointing. He was really looking forward to teaching comics out there. That dream was one of the things keeping him going.”

“For years, we had a joke, because I complained all the time about him using smelly, toxic, lead-based enamels. ‘They’re killing you,’ I’d say. And he would carefully remind me of their great qualities, how they could deliver a flat, even surface, how well they laid down, even on glass, and all that. No need to double or triple-coat, etc. ‘Worth it,’ he’d say. Then he’d tell me again what he said so many times, ‘Just put on my headstone: He Died For Greater Opacity.’”

Tyler wrote an obituary for Green which she posted on her Facebook page, which said in part:

Hark! Ages! Prepare to Receive a Great One in Glory!

And we understood that a coterie of plaid-clad brooding angels had set an infinitely long table to showcase his brilliance:

Drawn pages, pens, inks, brushes, paints, signs, his gold leaf kit (as the pearly gates apparently need a touch-up). There are scripts, notebooks, guitars, sheet music, coffee making supplies (essential), mystical talismans, books, correspondence, empty jars, receipts, stir sticks, and

all those things that say ‘I built a life. I loved my family. I valued my friends. I did quality work and shared my gifts, and, of course, (using his words) — (how often we’d heard him say):

“I’ll be in touch.”

Green is survived by his wife, Carol Tyler, two sisters, Karin Moss and Eve Green, two daughters, Catlin Wulferdingen and Julia Green, and he has two grandchildren. A memorial exhibit and celebration are scheduled for early October 2022 at the (DSGN)CLLCTV gallery in Cincinnati.