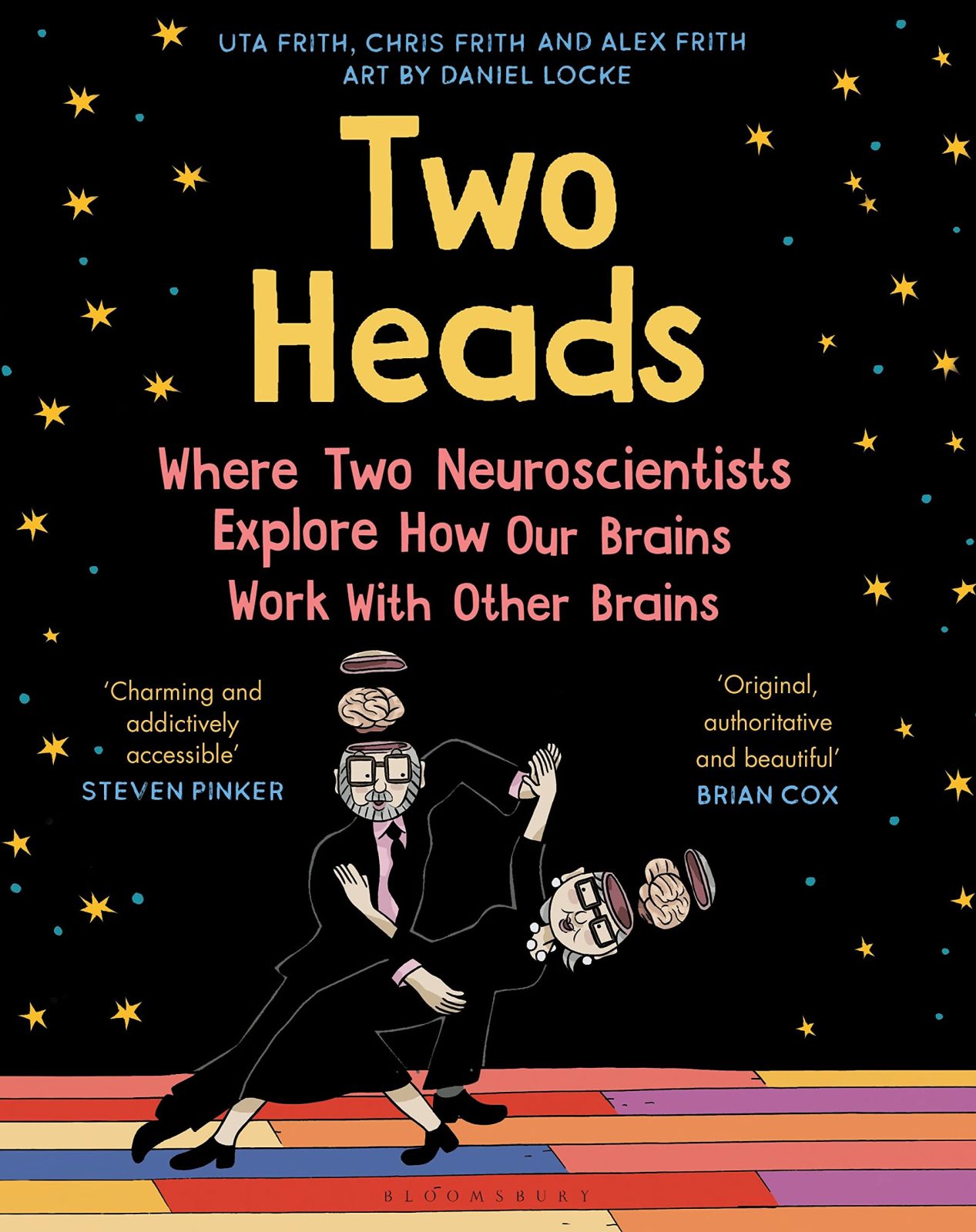

I've known Daniel Locke for several years and he's always busy making comics. Like really busy, up to his neck in it. What interests me about Daniel's work is it's impossible to pigeonhole, to categorize. His medium is always comics, but he's not tied to one particular genre or group. I've seen his comics in a gallery setting, as public art, giant murals, Risographed alt-minicomics, academic infographics, quiet autobio and fantasy RPG zines. He covers all the bases and, importantly, seems to have fun along the way. His latest book, Two Heads, published by Scribner in the USA, Bloomsbury in the UK, is a deep dive into the nuances of the brain and scientific understanding of it. Complex stuff but not beyond the casual reader, I'll let him explain.

-Joe Decie

* * *

JOE DECIE: Hi Daniel, tell us about the new book.

DANIEL LOCKE: Two Heads is a nonfiction graphic novel that was published in the USA and UK earlier this year. I provided the images and the text was written by the author Alex Frith, in collaboration with his parents Uta and Chris Frith; famous professors of neuroscience at University College London. The book is about our understanding of how the human brain works, and how we know how it works. It also outlines the professors’ thesis that our brains have evolved to work in conjunction with other brains. The story is told through the lens of Uta and Chris’ careers and spotlights Alex’s lifelong ringside seat.

Working on it has been a real dream. It has been an enormous privilege to have had the opportunity to make the artwork for this book and in the process learn about something so fundamental (as the operation of the brain that was making those drawings).

This alongside your previous book, Out Of Nothing, have both been massively ambitious, far-reaching nonfiction explorations into science. Why science, Dan?

I’ve always been a fan of science, ever since I was a kid, just as I’ve always been a fan of comics. Science was a close second in terms of favorite subjects at school. But how I ended up working with scientists in my comics work has a very particular starting point.

In 2009 my wife was pregnant with our first child. At the time I had contributed to lots of comics anthologies but was mainly working as a teacher in various educational settings. We needed more money coming into the house and I really wanted to get my own art practice off the ground. That summer I applied for every position I could find that called for an artist, or at least someone who could draw. I must have sent off about 1,000 applications. At university I had studied fine art (for the first few years of my career I mainly made sculpture and videos), so most of the positions I applied for I found in the art world press, places like the Arts Council England website or a-n Magazine.

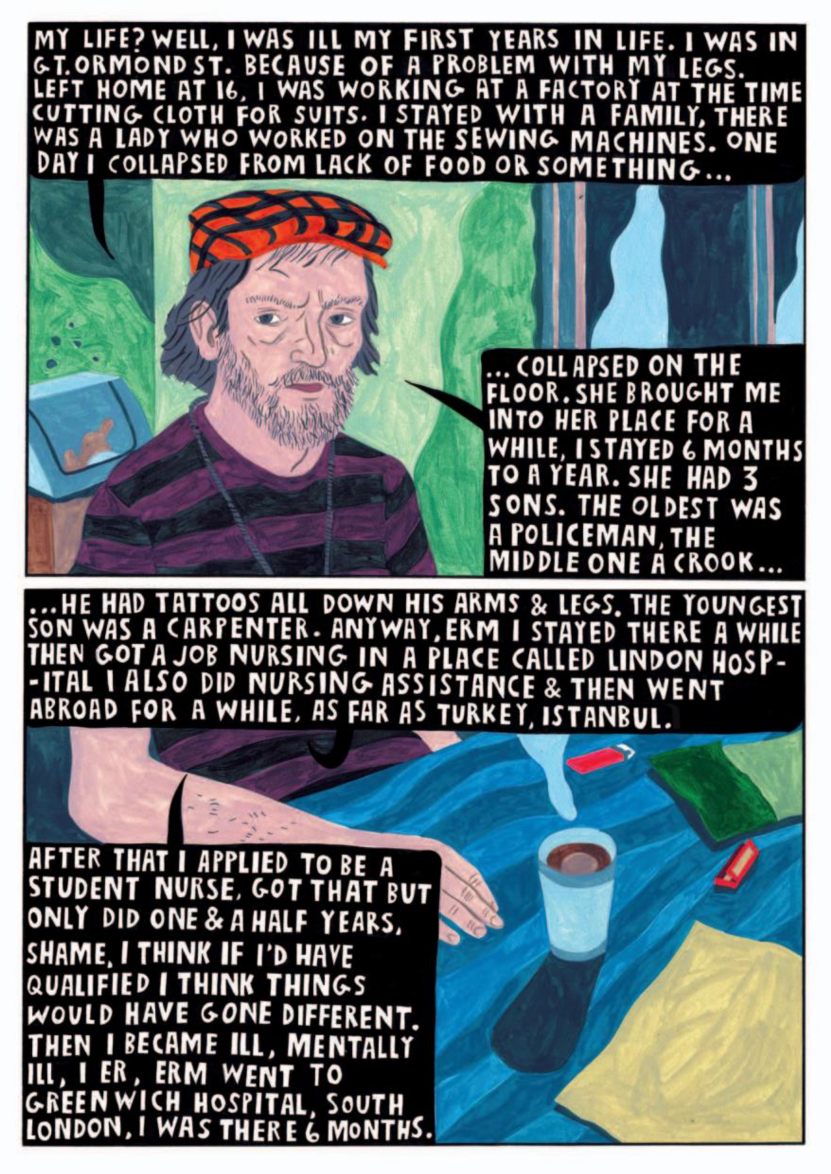

This round of applications resulted in a bunch of really interesting jobs. I worked on a reality TV show for a few months (my mum loved this job even though I only actually featured in one or two of the finished episodes) and did some interesting residencies, one of which was in Morocco with an amazing group of artists and musicians. But the job that had the greatest impact on me was a residency in Islington, North London. For three months I worked in a housing association called St Martin of Tours.

St Martin of Tours specializes in providing homes and care for men with complex mental health issues. I worked in a branch of the [housing association] that supports individuals with a forensic history, meaning in their pasts they had committed serious violent crime and served time in prison as a result. During the course of my residency I got to know the community living in the building, both the men and the amazing staff that supported them, many of whom are forensic psychologists. This was the first time I had had the opportunity to work closely with people who had scientific training. I really enjoyed it.

I produced a comic strip portrait of the place and some of the people I had got to know there. We printed these as a newspaper-style publication and handed them out for free in the local community. This was at a time when free newspapers in London were fairly new.

I loved the experience of working with the psychologists at St Martin's and I also felt really privileged to have had the chance to use my skills in a socially engaged way. I always felt that I wanted my own art practice to reflect my personal values of inclusivity; I feel strongly that culture, art and comics are profoundly important and should be available to everybody. This project seemed to provide me with a way of examining these ideas as well as engaging with science and scientific thinking.

I feel like around that time the potential for comics to be used as a tool or device was really beginning to be explored. Maybe partly because, as you said, out of necessity to make money, many of us started to introduce comics as a form of public art, art therapy, graphic medicine, etc.

The need to make money and the practical day-to-day demands of maintaining an art practice are really important. It's something that was never discussed when I was at art college in London. Maybe because I studied Fine Art. (God I really hate that term; I wonder if it's used internationally to define gallery-based art? I'm sure part of the reason I ended up making comics was tied to a rejection of the idea that some art is 'fine' and other art is, what? Coarse? Crude?)

I absolutely love what Graphic Medicine do. It's really inspiring to me to see comics makers, or cultural practitioners generally, getting out of whatever specific context they are used to and making space for themselves elsewhere.

But that is what you do, find a area where comics didn’t exist, and use comics to explore that world… be that mental health, science, nature. You more than any cartoonist I know are pushing comics into the public eye. Pursuing avenues to get our artform out there.

That's really kind of you. I guess when you're inside something it's hard to know how it appears from the outside. I can tell you that from the inside it feels pretty chaotic most of the time. Since I started doing this full-time, 12 or so years ago, I've more often than not had a number of projects on the go at once, and because those projects frequently involve collaborating with someone from a field totally different to mine, there's usually a pretty high learning curve and a lot of plates to keep spinning.

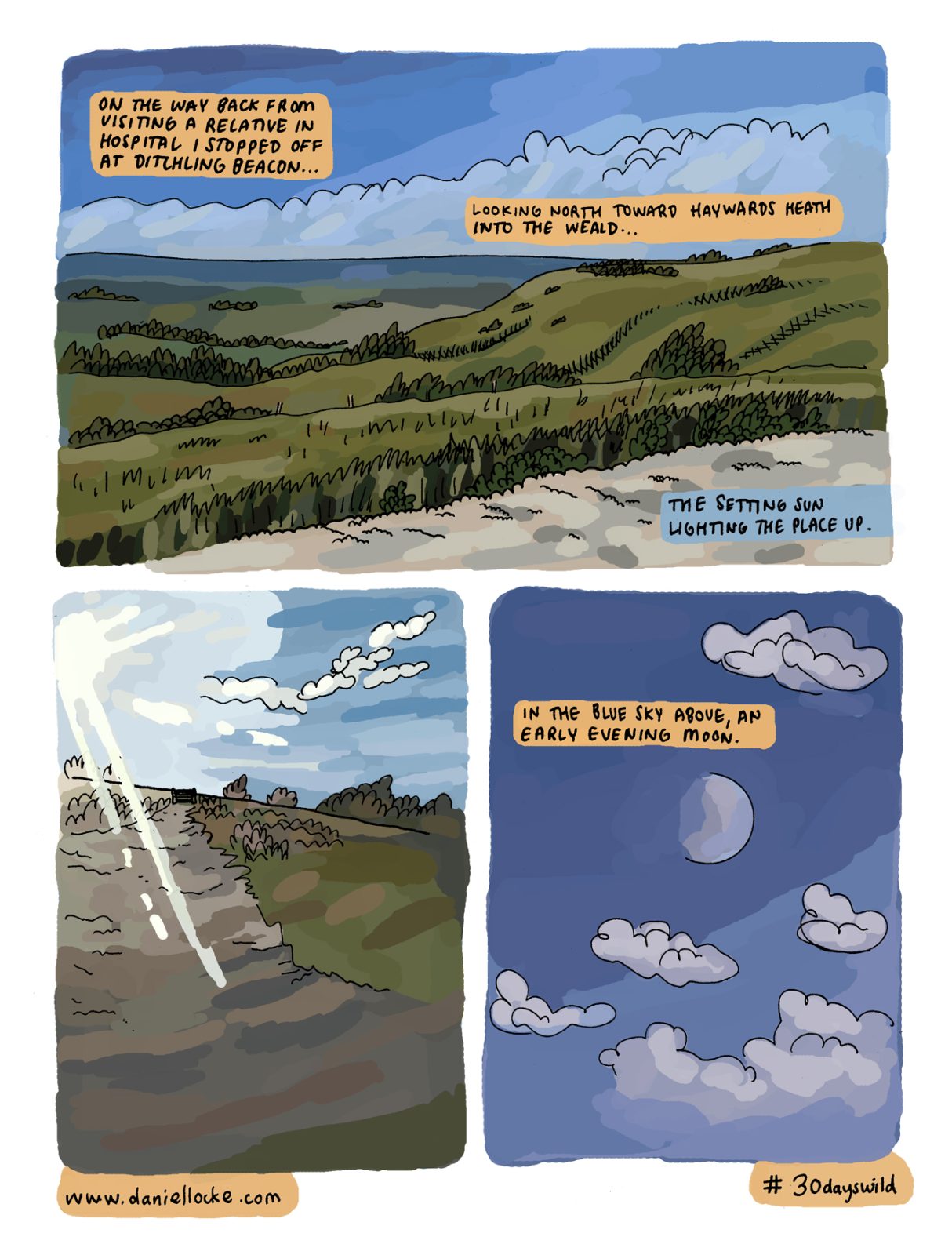

One of the aspects I most like about working across different areas of expertise is the opportunity it presents to learn about something new. For example, I started working with a small organization called Rewilding Sussex about 10 years ago. It's run by a lovely man called Dr. Chris Sandom, now a lecturer at the University of Sussex. When I first started collaborating with Chris and his friends at the charity, I knew nothing about the concept of rewilding, but over the course of a number of different projects I feel like I've learned a lot about a really interesting subject. I actually feel pretty strongly that rewilding should play a part in how we organize our societies. There should be more consideration for the space that the natural world needs.

The comics I've made with Chris and Rewilding Sussex have tried to communicate, as impartially as possible, the facts associated with rewilding, offering up possible definitions of the concept, or inviting imaginative applications of rewilding in different settings - urban, agricultural etc. I'm proud of this work because although it might not be the type of comic you'd take with you on a beach holiday to read in the sun, I think it's doing an important (albeit small) job of facilitating engagement in the vital discussion around the climate crisis.

There seems to be so many untrustworthy sources of information floating around right now. I feel a responsibility to be working in some small way against that trend. It's probably stupid of me but I feel a sense of duty as a communicator to be using some of my time to ease the passage of truth out into the world. That sounds so over the top! Don't get me wrong, I'm aware that what I'm doing is pretty small beans, but you know, you do what you can. [Laughs]

You've taken comics into all sorts of different settings too though, Joe. I'm thinking about the work you've done for different universities over the years.

Yeah, I’ve done a bit, but I keep that work for academics separate from my art practice, mostly because I’m just drawing their stories, it’s not my work. My input is minor, some explanation of how comics work best, then I just draw up what they tell me. Whereas your comics with academics and scientists seems far more involved, your voice is present in the strips, I see them very much as collaborations rather than you as a hired illustrator. Can you tell me about that, how your collaborations work?

Sure thing. You know, it's funny, given how deeply a part of my working life collaborating is now, but when I was at college I found working in teams really challenging. I loved to work solo, quietly in my corner of the studio, stopping occasionally for coffee or a chat. Nowadays, working with others, building partnerships - it's a vital part of my career.

There are a range of different types of collaborative relationships within my practice. There's the type that exists when I'm working with a non-artist. I'll work with this type of expert in deciding the content of the final piece. I'll rely on them for the hard facts, I'll offer up ideas for how we might position that information within a narrative framework and then share my work-in-progress. Sometimes, as in the example I spoke about with Chris Sandom, a friendship develops that allows the collaboration to deepen.

Then there are the much more remote collaborations with external organizations, galleries or universities. These tend to be formal but are so important to build. Without them it's really difficult to secure funding and get projects off the ground.

Finally there are the collaborations with other artists. These can be super-fulfilling, but they have the potential to be the hardest to navigate, I guess because both parties are playing on the same turf, if you understand my meaning? I feel incredibly lucky to have been able to explore this type of collaboration with other artists who I respect and whom I consider friends. I've worked with Karrie Fransman in this way, and most recently Hannah Eaton, two amazingly talented cartoonists, as well, of course, as you, Joe!

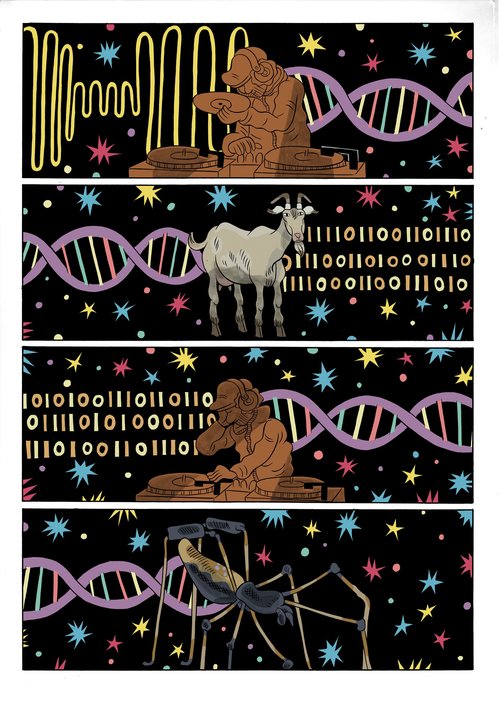

The person who I’ve worked most regularly with is the video artist David Blandy. I call him a video artist, I guess that's the type of work that he's well-known for, but he uses a wide range of media, most recently turning his hand to TTRPGs [tabletop role-playing games]. David and I worked together in 2013 on the Wellcome Trust-funded Helix. Helix is a multimedia artwork that was commissioned in celebration of the 60th anniversary of the discovery of DNA.

Helix is a really significant work for me as it directly led to David and I being invited to further explore its themes in a larger work. That work ended up being our book Out of Nothing. I'm pretty sure TCJ featured a review of it. I seem to remember it was a mixed one? I'm not sure, I do remember that the Guardian loved it though! [Laughs]

Recently I've been working in a new collaborative way that I'm really excited about. I've been using creative workshops to explore possible themes and ideas for public artworks with specific communities. I've been building these workshops around the making of short comics, meaning that each participant gets to learn something new about how to make a comic strip as well as contribute to the content of a larger artwork.

I used this method of working when making my seventeen-meter artwork Crucible for the Royal Sussex County Hospital's new building in Brighton, UK. The commissioning body was keen that the content of the artwork reflected the diverse nature of Brighton's population. So using my method of community design I programmed a series of free workshops, and explained to those who attended that what they made would ultimately contribute to the development of the themes of a new artwork for the city.

Once these workshops ran their course I took what was made and combined it with my own research into the hospital's history and then developed and drew the finished artwork. I'm really proud of this project as a lifelong resident of Brighton and Hove, I feel really privileged to have been asked to create something for the people of the best city in the UK (probably the world)!

It is a good town.

I've explored the use of community design in other projects, such as the work I did for the Martin Fisher Foundation's public health HIV Bus. Both of these projects are in my mind comics - they make use of comic book language and conventions, and in the case of Crucible are underpinned by the potential of comics to explore personal narratives and histories.

The making of Two Heads was a deeply collaborative experience; Alex worked on the script with his parents, then turned the script into a PDF file with suggested panel breakdowns and ideas for images. I would then provide a rough outline, with really rough pencils. Alex would rework these roughs as he edited the script, [and] I would, in turn, respond to his re-workings. In this way we developed a draft book. This draft itself underwent a series of edits and changes, until everyone was happy with the content, at which point I was able to start on the final artwork.

The making of Two Heads was a deeply collaborative experience; Alex worked on the script with his parents, then turned the script into a PDF file with suggested panel breakdowns and ideas for images. I would then provide a rough outline, with really rough pencils. Alex would rework these roughs as he edited the script, [and] I would, in turn, respond to his re-workings. In this way we developed a draft book. This draft itself underwent a series of edits and changes, until everyone was happy with the content, at which point I was able to start on the final artwork.

We worked on Two Heads for around four years or more. Over the course of that collaboration I got to know the Friths well - I think of them all as friends, and I think of myself as lucky to be able to call them friends. They are a lovely, generous and incredibly talented family. Alex is a very easy person to work with, he is patient and understands instinctively how comics work.

I mentioned earlier on that my work involves a lot of plate-spinning; I think that's partly a product of working with so many different people. I try to balance this and stay in contact with the Dan that worked quietly on his own in his corner of the studio by always having a small self-initiated project on the go.

There's a lot of wildly different projects here, and others I know your work from: fantasy D&D-type stuff and some autobio family comics. I admire your diverse subject matter, but what is it you like to make most? I mean, if there wasn't a need to make money from comics... or are you just happy to draw, regardless of subject?

That's a great question. I mean, the need to make money is definitely not what keeps me in this game, there have got to be easier ways to do that! [Laughs] And whilst I absolutely love to draw, I reckon I'd do that if it was a job or a hobby. I think fundamentally what I like is to hear and share stories, and I guess there's just something about drawing and comics in particular that I find endlessly fascinating and full of potential.

During the first lockdown in the UK, when everyone started to feel anxious and unsure, the government was slow to act and people stopped sending their kids to schools, stopped going to work, on their own initiative. It was a crazy, stressful time. I've never know anything like it, I mean, none of us have, right?

In that moment, my first instinct was to reach for my sketchbook and make a comic about life at home. It was a totally selfish act. Making those comics were reassuring to me. I hope it doesn't sound stupid but making those comics gave me a sense of control over what was happening to me and my family. It might have been an artificial sense of control but it helped me to keep the boat afloat during a turbulent time.

If I could do anything, I reckon I'd just keep doing this.

I loved those comics, your interactions with your kids, their worldview - it was quite touching. I don't think it was a selfish act at all. I guess with autobio there's always a risk of navel-gazing, but moreso it's finding connections. I don't mean making “relatable content” but finding themes that flow in our lives, things we do the same, things we do different.

I'm pleased you enjoyed them. There's nothing better than hearing that an artist you admire likes what you've done. I agree with you about autobio comics, there can be an amount of navel-gazing, but it's that promise of finding connections or things that resonate that makes them so appealing.

Autobio comics were some of the most important in convincing me to re-orientate my practice towards making comics after I left college. I absolutely loved Gabrielle Bell's work and Julie Doucet's Dirty Plotte in particular. My comics history is absolutely terrible but there were some fantastic books put out in the '90s/'00s, right? I'm thinking about David B's Epileptic, Satrapi's Persepolis, and so many others. So around that time, when I was finding myself drawn back into comics shops after a bit of an absence, those where the books I was attracted to.

The comics I made during the lockdowns were really coming off the back of a series I did for a website called Popula in 2019 (I think). I guess the series was called Elements (at first it didn't have a continuous title). Initially I pitched the idea of doing a comic for each of the four elements, Earth, Wind, Water and Fire. Each comic was built loosely around a personal memory or interaction with one of those elements. The idea was to poetically/personally riff on something vaguely science-based.

This was really a dream job. I worked with Trevor Alixopulos and Vanessa Davis, both brilliant cartoonists. Vanessa's work had been some of that work that I found really inspiring when I first started, so it was a little daunting knowing she was assessing my monthly submission.

Yeah, Vanessa's fantastic.

Coming back to the question you asked earlier, about what it is that I would like to do, I think [Elements] is something I'd like to do again. I recently had the idea of pitching a similar type of strip, where I reflect on visiting a local, small or regional museum each time. I'd like to do that, I love museums with a passion and would enjoy the chance to share that love. If there are any editors reading, feel free to drop me a line, I always meet deadlines, work like a beast, and I'm happy to respond to editorial feedback! [Laughs]

That does sound good, I might know someone.

The comics I did for Popula sort of ended up segueing into the work I've done for The Nib. That's not strictly-speaking autobiography, more journalism, but it does have a touch of an autobio approach to it.

What you said about being happy to respond to editorial feedback - can we talk about that a bit? Coming from a DIY background, I found all that quite difficult, but that must be something you get a lot of, working with a whole host of contributors, big teams.

I've definitely had some bad experiences, but luckily more good ones. I see it like all human interactions; some work, others just don't. There's a weird magic involved here I think. A delicate mix of personalities and emotions. I was wondering what it was that you find challenging about working with an editor? I mean, there’s a lot that is potentially tricky in that relationship, but on the whole I’ve found my experiences to be more positive than negative. Each editor I’ve worked with has been so different from the preceding one. What I like about it is the privilege of having a pair of eyes on a new work before it goes out into the world and has to fend for itself.

Yeah, it can be difficult to look objectively, beavering away on your own.

I guess I approach my interactions with editors in the same way as I engaged with crits in college. It’s interesting to hear feedback on a work from an informed person, who’s invested in making the work good in the same way I am. But that the work ultimately belongs to me and their opinion is just that, an opinion. I think the key elements of this relationship are trust and respect. I should say, though, that I prefer 'light touch' editors than working with someone who wants to really get right down in the weeds of a project-- actually, do I? I’m not sure about that. It really depends on the project, who it’s for and what I want to achieve with it.

Despite your very broad choice of subject matter and collaborators, your works are always instantly recognizable as a Daniel Locke comic. Your voice, your visual language is quite distinctive.

That’s reassuring to hear. I tend to think of my work as being a bit all-over-the-shop. I have this problem; when I sit down to start work on a new project, I feel as though I’m starting from scratch. It’s as if I’ve somehow forgotten how I made the last project, or maybe that I sort of want to get away from it. All this results in a portfolio of work that I feel doesn’t always look as though the same person made it. At least that’s how it can feel, so it’s nice to hear that on some level the work is hanging together in a sort of ‘Dan-ish’ fashion. I honestly think I’m the worst judge of my own work. Do you know what I mean? Maybe everyone feels like that?

You're not alone!

I was trying to work out what art most inspires me, and it dawned on me that a lot of it doesn’t look at all like what I do, or even share similar interests or themes. I’ve been really enjoying getting back into galleries lately, you know - after the pandemic. (Not that the pandemic is even over, but you know what I mean.) I recently saw an incredible film at a space called the De La Warr Pavilion, here on the southeast coast of England.

The film is by Bassam Al-Sabah and is called I Am Error. It examines things like gender identity within a military context, but draws imagery from video games and anime. It really fired me up, the way the figurative imagery morphed into abstraction and the dance between subtitles, soundtrack and pictures. SO good.

At that same venue a few years ago there was a retrospective of the Chicago Imagists, the Hairy Who and what not. That was an awesome show. Most often I tend to like individual artworks rather than an artist’s whole body of work. I think a lot about Christian Boltanski’s early artist books. And Ilya Kabakov’s The Man Who Flew into Space from His Apartment. I love Kuniyoshi and Bawden and Sendak. The covers of Ladybird books and Erik Hesselberg’s Kon-Tiki and I.

I think a lot of my work draws inspiration from imagery that was around me when I was little. I find the work of illustrator Pauline Baynes really appealing. There’s a clarity and straightforwardness to her illustrations that I absolutely love. I also really like the backgrounds of the wild, volcano filled landscapes of the He-Man [Masters of the Universe] packaging of the 1980s. Those images really stay with me! I must have spent hours staring at those backgrounds, peering past the drawings of Skeletor or Man-At-Arms into the world they inhabited.

I tried to channel some of that, I guess it’s a form of nostalgia(?), in my book Helms of the Multiverse. When I settled down to make that book I was thinking to myself, what book would my 12/13-year old self want to make? It’s a book of world-building, it’s really silly but it was so much fun to do.

I remember when I was a kid my favourite parts of the Asterix books were in the beginning and at the end of the adventures, when the narrative revolved around the normal daily life of the village. I used to so wish there was a book that just told the story of a regular day in Asterix’s world. Somehow this idea is tied to my childhood love of action figures.

When I was a kid the two things I loved best were Star Wars figures and comics. With the figures, I wasn’t so much interested in them as portraits of characters but as what they did to the settings you placed them in. What I mean is, by virtue of their scale, if you placed them in an area of, say, tall grass, that grass was instantly transformed into another world, a jungle or something. It was like magic.

Oh wow, yes.

Over the past couple of years I’ve been making my own (In)Action Figures, in an attempt to explore this idea. These childhood encounters with imaginary worlds and images and objects, they’re so potent. I think when I make a work I’m often trying to make something that ignites the intensity that I find when I remember those early experiences.

And obviously I love a whole bunch of cartoonists. There are just so many people making great work right now - you included, Joe! I’ve been really enjoying Adam de Souza’s work lately. After reading Taiyō Matsumoto’s No. 5, I just picked up a book from Drawn & Quarterly called Rave [by Jessica Campbell] that looks great. I love Gareth Brookes too. Living in Brighton I feel really fortunate to be surrounded by a community of incredible artists and cartoonists and illustrators. It’s hard not to be inspired by the things that are happening here. I listen to podcasts and audiobooks all day long. One of the bonuses of having a job that requires a lot of coloring-in is the freedom it gives you to soak up lots of audio-based info. I read a lot too. I’m currently enjoying Becky Chambers’ books. In my work with experts from other fields, I’m often introduced to ideas that really blow my mind. I’m trying to help other people experience those ideas as life-changing concepts.

Great, I'll let you get back to it then. Thanks, Daniel.