From The Comics Journal #297 (April 2009)

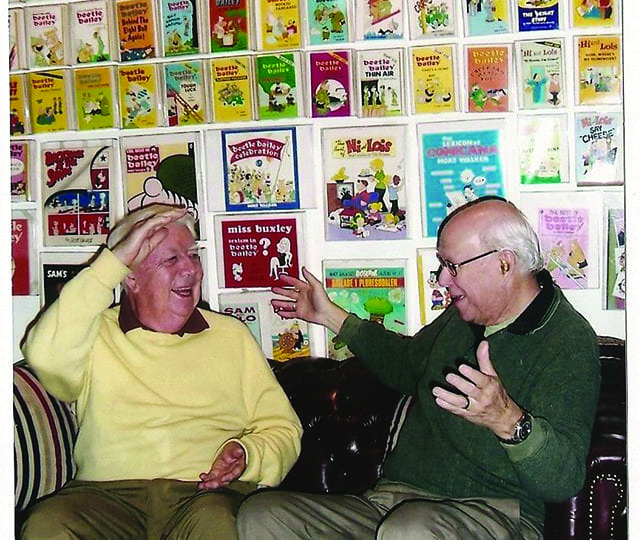

When I said I wanted to watch him draw a strip, Mort Walker said, “Sure,” and we got up from the conversation pit where we had been seated in front of the massive fireplace in what had once been the studio of Gutzon Borglum, sculptor of Mount Rushmore, and walked into Mort’s office around the corner from the stairway leading to the loft overhead where Mort’s assistant Bill Janocha labors daily. Mort had finished penciling his regular weekly batch of strips the day before — Monday, daily-strip drawing day — but he sat at his desk and pulled out another rough to convert to a finished pencil for my benefit. He put a small drawing board, maybe 18 by 24 inches, in his lap and tilted it, propping it against the desk, then picked up two pieces of artboard. He placed the smaller 5-by-17-inch piece on top of the larger sheet and, taking a mechanical drafting pencil in hand, he ran it along all four edges of the smaller rectangle, penciling the border of a strip on the artboard beneath. With the template still in place, he marked, on the artboard, the middle of the strip — where it would be divided into two panels — put the template aside, placed the rough rendering of the strip on the upper edge of the drawing board, and looked at his watch. Then he began to draw the first of the two panels, copying the compositions in the rough.

The day’s gag, roughed in a clean pencil sketch on 8.5-by-11-inch foolscap, featured only Beetle and Sarge: Sarge, seated at his desk, hands Beetle an envelope and tells him to deliver it, and Beetle promptly sits down, leaning against the wall. “What are you doing?” Sarge yells. Beetle says: “I never do any work without goofing off first.” Mort quickly sketched very lightly two circles to position the characters’ heads in the first panel, then he indicated their bodies’ positions with a couple outlining lines each. His blocking of the panel’s composition now consisted of two wraith-like apparitions, barely visible, entirely featureless like snowmen. Next, he lettered the speeches of the characters and drew the speech balloons. Then he turned to Sarge and, drawing a small rectangle on top of the head circle, he located Sarge’s garrison cap on his head, then drew the characteristic four-lumps that finish the abstraction of the character’s customary headgear. He then drew Sarge’s eyes, focused on the desk in front of him, then a round ball for Sarge’s nose. He drew the upper part of Sarge’s body, seated at his desk, and the extended arm and hand giving Beetle an envelope. Next he drew another rectangle — somewhat boxier, squarer, than Sarge’s — on Beetle’s head, adding a pointed bill to complete the fatigue cap Beetle usually wears. Then he put a perfectly round shape under the bill for Beetle’s nose. Beetle’s eyes, as usual, do not appear, obscured for evermore under the bill of the cap. After giving Beetle a body and tubular legs and arms, Mort went on to the second panel.

Every line Mort drew was exactly, perfectly, placed: none of the lines were sketchy, trial-and-error lines searching for the correct position. Sarge, the desk and Beetle were each outlined with single strokes. When Mort’s son Greg inked the strip, he wouldn’t have to choose which lines to ink: there was only one in every instance.

In the strip’s second panel, the composition, again faintly indicated with ghostly figures, was the same as that of the first panel, and Mort again copied the picture in the rough sketch, but when he drew Sarge this time, he changed the character’s position somewhat. Sarge in the rough is still seated at the desk as he is in the first panel; in reproducing that image, Mort drew Sarge getting up from his chair, leaning forward, supporting his bulk with his hands on the desk. Now, glowering down at Beetle as the work-averse private sat leaning against the wall in front of the desk, Sarge seemed much more threatening than he’d been in the rough sketch.

“You changed the pose,” I said.

“Yes,” Mort acknowledged. “I always try to improve things a little. And people like to see action in a strip, so I’ve got Sarge moving, getting to his feet, standing up.” He hunched his shoulders in imitation of Sarge’s pose.

With a few more strokes of his pencil, Mort finished drawing Beetle, completing the strip. He looked at his watch again.

“Ten minutes,” he said. “I could do the rest of the week’s strips in what remains of an hour.”

And why not? By the time I witnessed him at work on this day in mid-December 2008, Mort Walker had been drawing Beetle Bailey for 58 years and three-and-a-half months. His hand and eye knew their tasks so well that he scarcely needed much time for them to turn in another perfect performance.

As the Chicago Tribune’s legendary editorial cartoonist John T. McCutcheon said when he acquired the title after half-a-century of cartooning, “If you live long enough, you get to be dean of cartooning.” Or words to that effect. And Walker, at 86, has not only lived long enough, he’s also been drawing a daily comic strip, Beetle Bailey, for longer than anyone else in the history of American cartooning.

Beetle Bailey started in 12 papers on Sept. 4, 1950. With about 1,800 subscribing newspapers today, it ranks as one of the world’s half-dozen most popular comic strips. And Walker also created another of the top circulation strips with over 1,000 client papers, Hi and Lois. Beetle at first chronicled the lackadaisical under-exertions of a lassitudinal college layabout, but even though it was the sole college-themed strip on the syndicated horizon, it gained only another dozen subscribers over the next six months. Then Beetle enlisted in the Army on March 13, 1951.

The strip began picking up more papers, and when, in January 1954, the Army’s newspaper, Stars and Stripes, kicked the strip out of the paper for making fun of officers, the circulation of Beetle soared. “Papers all over the world ran stories about how the Army brass had no sense of humor,” Walker remembered.

Although the strip is ostensibly about military life, Walker’s Army is just another version of society at large, which sustains its essential order through a hierarchy of authority. From the point of view of most of us in a social order, the flaws in the system are due to the incompetence of those who have authority over us. Beetle Bailey encapsulates this aspect of the human condition and gives expression to our resentment by ridiculing traditional authority figures and by demonstrating, with Beetle, how to survive through the diligent application of sheer lethargy and studied indifference. But the ridicule is gentle: It takes shape as Walker repeatedly shows us that everyone in his army — authority figure or not — is but a bundle of personality quirks. Hence, the strip is a great leveler.

More than a satirical statement about the human condition, Beetle is also an achievement in the art of cartooning. Over the years, Walker’s style has evolved. At first, he drew in a simple big-foot style that seemed a mix of John Gallagher and Tom Henderson, two great magazine cartoonists of the ’50s. But as the years rolled by, Walker refined his work, streamlining simplicity into a unique comic abbreviation. By the late ’50s and early ’60s, Walker’s patented stylized forms had emerged. Not since Cliff Sterrett surrealized human anatomy in the futuristic manner in Polly and Her Pals have we had such charming comic abstractions of the human form. The flexibility of Walker’s abstracted simplicity is capable of extreme exaggeration for comic effect. Indeed, much of the humor in many strips arises from the antic visuals as much as from the situation depicted. In short, Beetle Bailey is an artistic achievement of the first water.

Walker’s colleagues long ago recognized his skill and talent: the National Cartoonists Society awarded him the Reuben as “cartoonist of the year” in 1953, and he has since received every accolade NCS can bestow. In 1959-60, he served as president of the group and has maintained active participation in its affairs ever since. He has also received the Pentagon’s highest civilian award in spite of the military’s often markedly cool reception of Beetle Bailey: the Air Force had Steve Canyon; the Navy had Buz Sawyer; for awhile, the Marines had Dan Flagg; and the Army had — Beetle. But Walker has maintained he was happy not being a “spokesman” for the military: “It would have killed the humor,” he said.

Born in 1923 in El Dorado, Kan., Walker sold his first cartoon at the age of 11, and by the time he was 15, he was drawing a weekly comic strip for one of the city’s grown-up newspapers. By late 2008, when I interviewed Walker at his studio, the output of “King Features East” (as the Walker enterprise was once dubbed) had been reduced, practically speaking, to two strips: Beetle Bailey and Hi and Lois. Sam and Silo was also still in circulation but done entirely by Dumas. Hi and Lois was produced by two of the Walker sons, Greg and Brian, who write the gags, and Dik Browne’s son Chance who pencils the strip for Frank Johnson’s inks. The gag-writing team for Beetle is Mort, Brian, Greg and Dumas.

Walker’s staff on the premises is his son Neal and cartoonist Bill Janocha. Their duties are varied, extensive, and unclassifiable. Neal maintains the mortwalker.com website and its sundry subsets, and he and Janocha produce new Beetle Bailey material for comic-book publication in Scandinavia, where Walker, thanks to Beetle’s popularity, enjoys rock-star status. Janocha joined the Walker operation 21 years ago, ostensibly to assist on Gamin and Patches after its launch, but his assignment quickly expanded. Recently, Janocha helped secure a contract with a Canadian studio to animate Beetle Bailey, Hi and Lois and perhaps Boner’s Ark for TV series or direct-to-DVD productions.

Seeking both status and respect for the medium, Walker established the Museum of Cartoon Art in 1974. Over the years, Walker has spent millions of his own dollars and countless hours of his time fund-raising for the Museum and promoting it.

Walker sees both the social and the personal aspects of cartooning: “As society becomes more spread out, family members find themselves living farther and farther apart from each other, and with life becoming more impersonal, comic strips help fill the void in people’s lives by creating the illusion of friends and shared experiences.” As a personal enterprise for a cartoonist, “the comic strip,” he continued, “is one of the few media that allows one person to express his philosophy, his anger, his joy and his disappointment without outside restriction. It is one of the purest forms of art and expression that exists.”

As Walker settles into his less frenetic pace now that his beloved Museum has found a home that he needn’t sustain with personal effort and funding, he reflected, during our conversation Dec. 15-17, 2008, on a long and productive life and career. One casual remark by Walker as he looked back over the years, provides a good indication of what it is like to hang out with him: “I still have the same friends,” he said.

Transcribed by Angelica Blevins and Gavin Lees

R.C. HARVEY: At one point in about 1984, ’85 or ’86, you and the people around you were producing six comic strips. Six daily, syndicated comic strips. Now you’re down to three, right?

MORT WALKER: Yeah. Silo Sam, Hi and Lois and Beetle. We’re still selling Boner’s Ark in overseas markets, although we’re not doing any new stuff.

At the same time, you and your crew were producing the Beetle Bailey comic book and you were also actively involved in operating the Museum of Cartoon Art, which has now gone away, its holdings bequeathed to the Cartoon Library and Museum at Ohio State University, relieving you of a huge demand on your time and energies. So the question is: Mort — what are you doing with all your spare time now? [Laughter.]

I’m always into something else, and I’ve got my new magazine, The Best of Times. I’m working on that, and designing the covers, and helping — well, I run the whole thing with the help of my son Neal.

Tell us about that.

Well, for years I’ve had this idea of producing a magazine with reduced cost. King Features has about 140 features that it syndicates. The local paper only uses 10. So I thought, well, there’s 130 well-known writers and artists and cartoonists who nobody sees around here. And there are other communities like this. So I thought I could make a whole magazine out of this material and sell advertising in it, never having to pay salaries, or anything like that. So I went to King Features and I told them the idea. Of course, everyone, as they usually do, pooh-poohed it. They said, “Oh, you’ll never do it.” They got three salesmen to come to the meeting to talk me out of it. And they may be right. [Laughs.] We’re still struggling with it, especially since the economic crisis has cut down on advertising and people spending their money somewhere else.

Bill Janocha, your long-time assistant, mentioned that there’s some sort of animation.

We have a new contract. Just signed it last week.

This is a contract with whom?

An animation studio in Canada.

And they want to do animation for television?

They want to do all kinds of stuff. We haven’t really settled on it. They were going to do short stuff, then we were going to do half-hour shows, stuff for computers and cell phones and all kinds of things. We’ve had a couple meetings and they want to do Beetle, Hi and Lois and Boner’s Ark. So, that might give me a little work here and there.

Yeah, right. You can’t stay away from it. Not only were you producing six strips at that same period — this is 1984-86 — I think the comic book was still coming out then, and you had seven kids.

And Cathy had three, so we had 10 all together. [Mort married Cathy Prentice née Carty in 1985 after both their first marriages fell apart. Mort’s first wife was Jean Suffill of Kansas City, whom he met and dated while they were both in college at the University of Missouri.]

So now, you can just loaf, right? [Laughter.] Comparatively speaking.

I read an article the other day in Psychiatrist Magazine about procrastination, how people sit and do all kinds of things to keep from going to work. They’ll sit there and twiddle, talk on the phone, go get a drink of water — they showed this guy with a pencil, shoving it up his nose and flipping it. And I began to think about some of the cartoonists. Like Dik Browne. He would get up in the morning, come down and have breakfast with his wife, and start drinking coffee and eating donuts. And they would talk and laugh and everything like that. And he consumed the whole dozen donuts. He wouldn’t get to work, and then he’d go up and take a nap. He’d come down after the nap and he’d work sometimes in the middle of the night. I know a lot of cartoonists who do that, they work at night because they don’t get to work during the day.

It’s some crazy thing I’ve got, this compulsion to get things done and finished. I’ve got in trouble with it before. I had a contract with Crayola to do advertising for them. I sat down and did a poster, took it to them the next day, and they said, “Wait a minute! We haven’t even had a meeting on the theme yet!” [Laughter.] I get in trouble every once in a while for sitting down and going ahead and doing stuff before people have a meeting or get their budget together, and they have to take it up to seniority and get approval and study it some more and eventually get around to doing it. It’s like this animation contract. It took us a year! I hadn’t talked to them in a while and I thought they’ve lost interest because we haven’t heard from them. So I called the lawyer and said that I guess this isn’t working out. The lawyer took it as a criticism of her. [Laughs.]

So what took all that time? Just sorting out what kind of license they would have?

I think the woman who’s in charge took it over to Europe to a couple of the licensing shows or animation conventions. I think she finally got some interest. But what I’ve heard now is that somebody brought out a feature on chipmunks that have been around for a long time. All of a sudden — bingo — they’ve made something like $25 million in the past year. Maybe more than that; I don’t know the correct story. All of the sudden, they got the idea: “Whoa, you don’t have to have new features to attract attention. A lot of people like the old features, the old familiar characters.” All of a sudden now they’re looking for old characters like Beetle, who’s been around for a long time. For publicity, I said, Beetle’s been around for 58 years. It’s usually at the top of readership polls. We’re in about 1,800 papers, 52 different countries, with a readership of 200 million every day. Tell me another writer who has that kind of a readership. They’re thinking about nominating me for the Nobel Prize for Literature, just on the basis of the hundreds of books I have which are still coming out. [Laughter.] We have two out right now. We’ve got the first book in this country of the 58 years of Beetle. We have Sam’s Strip.

Yeah, that’s coming out. The Complete Sam’s Strip.

And then a couple other ones that [my son] Brian is working on, like the Lexicon of Comicana.

So that would be a reissue.

Yeah, but with new covers. Back when we did some of these books we really didn’t have a good publisher on it. They didn’t publicize it, they didn’t do stories on it. It was almost like they did it as a favor to us or something. They didn’t have any excitement about it.

There’s definitely a much better audience now and better market for stuff like that than there was 20, 40 years ago. A lot of it is made up of the comic-book fan community. They’ve branched out a little bit. And there are all those reprint collections from Andrews McMeel. I mean, that wasn’t going on 40 years ago, but it is now.

Years ago, I did this book Backstage at the Strips, which I wrote because every cartooning book I had on my shelf was all reprints from a book about comics in general. But never anything in the background about the cartoonist. I thought, some of these guys are interesting. They have stories to tell. So I went to work on that book, and my agent tried to find a publisher for it, finally she calls me and says, “I finally got a publisher!” So they put the book together, and then it went bankrupt a month later. They called me up and asked, “You want all your books?” He sold me each book for a dollar. I don’t think it ever appeared in a bookstore.

It must have appeared in a bookstore somewhere, because that’s where I got mine.

Did you? I didn’t get an advance on it, and I never got a sales report … [Laughter]

Let me try to put your career in some sort of context. If you had to name five significant events that shaped your career and life, what would they be? For example, just from what I know about you and your career, I’d be tempted to say Dik Browne was one of those five things.

Yeah. But I think first of all, it would be the cartoon editor of The Saturday Evening Post, John Bailey, encouraging me to create the college character who became Beetle. When I came to New York right after college, I was going to try selling gag cartoons, and I concentrated on The Saturday Evening Post because I had sold them one cartoon when I was in college. And John Bailey, who was the cartoon editor then — very friendly to me, very nice — he said, “Oh, I remember seeing your college magazine, ShowMe.” And he said, “You did great cartoons. I think we can work together.” So he started buying my cartoons, and one day after looking through some of my cartoons, he said, “You’re not married, are you?” I said no. He said, “You’re drawing family stuff, for married people and their kids. Why don’t you draw something you know about? Why don’t you draw about college?” So I started drawing college kids. And one day he looked at one of the characters and said, “That’s a funny-looking guy. Make a character out of him, and maybe we’ll buy it, like we’ve got Hazel for the back cover — make a feature out of him.” And that’s where Beetle came into being.

Spider.

Yeah, Spider. And then, it would be Sylvan Byck, cartoon editor at King Features Syndicate. He was my greatest mentor on earth for a long time. We’d have lunch at least once a week, and he’d feel me out on what cartoons are doing and what they liked and how Beetle was selling and everything like that. He was so friendly and so informative. I learned an awful lot from him.

Another cartoonist named Lew Schwartz was working up a strip about a family and wanted me to write gags for it. So I went to Sylvan and said, “Can I do a strip for another syndicate?”

He said, “Why do you want to do another strip? If you do, do one for us!” So I wrote some gags, and thought, I want to do a friendly family. Almost all the family strips I have, the husband and wife are always fighting. That seems to be the theme. The kids are mean little kids like Dennis the Menace, bothersome and pesky. I wanted to draw a loving family. Sylvan said, “OK, let’s find the best cartoonist available to do it. We’ll meet in a week, you’ll do a survey and I’ll do a survey and we’ll see if we can find the best cartoonists.” After a week, we looked at our lists and Dik Browne was at the top of both of them. I said, “How’d you know him?” He says “I see Boy’s Life in my dentist’s office, and he draws a strip in there every month.”

The Tracy Twins.

Sylvan says, “How’d you find him?”

I said I saw his work in a bunch of cartoon ads — Campbell’s Soup Kids, Lipton Tea, different styles. Everything he did was different styles. So I said, “Let’s find out where he is.” And Stan Drake says, “I know him. He works for an advertising agency in New York.” He gave us the name of the agency [Johnstone and Cushing], we looked it up in the phone book, called up and said “Is Dik Browne there?” He came to the phone and Sylvan said, “Hi Dik, this is King Features calling. How would you like to do a strip for us?”

He said “Yeah, OK” — and hung up!

I said, “He doesn’t seem to be very enthusiastic about it.”

The phone rang and it was Dik who said, “Did you just call me?” [Laughter.] He thought it was a trick! He said the minute he hung up, “I looked around to see who was missing in the bullpen. I thought somebody was playing a trick on me.” He got all excited about it.

I’d never met him before. We got together and he took me down to the agency and he said, “Here’s all the different styles I draw in.” He drew some in a design-y style, and for another thing he’d be different, a more affectionate style with nice round heads. More complete.

I looked at all the different styles and I said, “That one.” And that’s the style he used in the family strip, which is Hi and Lois. [Launched October 18, 1954.] He was so good. He and I did a couple of books together. He got unleashed on doing a book and he’d draw complicated backgrounds and scenery. He was a smart one. It was a wonderful friendship. I was always cracking the jokes and he’d get mad at me, but then we’d get back together again.

One day we’re coming back from some sort of a function in New York — we’d all been drinking and laughing — and we had a limousine. Dik was sitting in the front seat and there were about four of us in the back seat. We were laughing and talking and we came down the street in New York where there were these funny-looking trees. We said, “Those are some funny-looking trees.” Dik says, “Oh yeah, that was a gift to the Mayor of New York from the Emperor of Japan,” and blah blah blah.

So he’s telling us all about these trees, and I said, “Ahh, more Dik Browne bullshit.” [Laughs.]

God, did he get so mad at me. We got back to my studio and everyone was coming in for a drink and I went to open the door and said, “Aren’t you coming in, Dik?”

He says, “No!” and slammed the door.

I said, “Oh, boy.” I had to call him up on Friday and said, “Hey Dik, we’re playing golf today. Come on.”

He said, “OK.” [Laughter.]

I have that trouble every now and then, trying to be funny. I had a guy work for me for years — you probably can’t print this, but — after playing golf, we’re sitting around drinking and talking about Dik Browne. This guy says, “I like Dik.” I said, yeah. He goes, “No, no, I really like Dik.”

I said, “That’s what I hear; you like Dik.”

And all of a sudden he says, “I’m never going to speak to you again!” [Laughs.] He thought I was calling him a homosexual. He was one of my gag writers, and I brought him along because he showed me some strips he was trying to sell and they weren’t selling. He says, “What’s wrong with them?”

I said, “I don’t know. You know something? I like your gags. You’re a good gag writer.”

He says, “Oh really? The other strip I had, my partner wrote it, I just drew it. Now I’m trying to write my own.”

I said, “You’re a good gag writer.” So I hired him to work on Boner’s Ark.

What makes a good gag writer? I mean, if you look at 10-12 strips that somebody’s done and say, “This guy’s a good gag writer,” how can you tell that?

Well, you have to have a surprise at the end. What I find is that when we write gags here, oftentimes the end is pretty predictable. I mean, it’s a normal thing to take two steps in the setup and you end up where you’re supposed to end up. That’s just reasonable, it’s not funny.

If the setup has step one and step two, there are only two or three possible ways to end it, and if one of those endings concludes the strip, then the strip is

predictable.

Yeah. I always like to have some funny visual in it. This is my formula. Funny pictures. I keep after the guys. I say, “Talking heads are not funny. People are going to turn the comic pages and if Beetle has his head stuck in an elephant’s mouth, they’re going to say, ‘What’s going on there?’ Visually, it’s a comic strip and you’re a cartoonist. So let’s have some funny pictures.” This is my formula for all my guys. If it’s just two heads talking, I have one of the guys doing something funny.

The drawing has so much to do with it also. My favorite strip these days is Zits. Borgman has just a fantastic ability to stretch arms all the way across the whole strip and draw people in such funny, convoluted positions. The mother’s talking to the son and she’s leaning over backwards and her head’s on the floor, practically! [Laughs.] Things like that.

He’s really a master at this kind of stuff. There’s a large percentage of his stuff that could not appear in any other medium except a comic strip.

And it’s also very realistic. This is the way kids are — they drive their parents crazy! [Laughter.]

Tell me some more about Sylvan Byck.

He was a sort of a cartoonist himself early in his life. I think he worked for the Brooklyn paper.

Yeah, the Brooklyn Eagle.

He was just a very nice guy. He was so helpful with me; I couldn’t understand how he spent so much time with me. I think he was very instrumental in taking me off into success.

In addition to Sylvan Byck, Dik Browne and John Bailey at The Saturday Evening Post, are there any other watershed events like that you would include in a role call of five?

Going back into an earlier time in my life, my father was a poet. Growing up on a farm, he would get up every morning at 5 o’clock to feed the cows, but in Kansas City, we didn’t have any cows any more so he’d get up every morning and write a poem before he went to work. Every day. And the Kansas City Star would publish them. So he would usually go down to take his poems in when he went to work down in the city. While he was talking to the editor, I would go over to the big art department. They had a guy who did a comic strip, a guy that did editorial cartoons, and they had another guy that did a cartoon summarizing all the events of the week. Then they had other cartoonists, too. At one time, they hand-lettered all their headlines on the front page, instead of setting it in type.

So they had a big art department, and they would let me sit there on the floor and go through all the originals. Then I’d show them the ones I wanted and take them home and put them on the wall. I think that was one of the most generous things that ever happened to me as a kid. All these cartoonists would look at my work, be nice and friendly to me, give me their work … my only comeuppance was that when I lived in New York and sold a comic strip, I went back to say hi to everybody and there was a different attitude — “Look what this stupid kid did! He went to New York and sold a comic strip!” [Laughter.] It was like they felt challenged by that or something.

The editorial cartoonist of the Star was S. J. Ray. He was still drawing cartoons when I lived in Kansas City.

Yeah, he was good. And Dale Beronius was the guy I liked, because he did this Sunday Wrap-Up with all the events in the city. And he was very good. He tried a strip himself one time, called The Candid Cameraman. It was all pantomime. The trouble a guy got into taking photographs. I think he was the most disappointed when I came in and showed him I had sold a strip but he couldn’t sell one!

A lot of the stuff you did as a kid and while working at Hallmark shows up in your autobiographical book, Mort Walker’s Private Scrapbook, and it looks like it’s drawn with a brush. Were you using a brush back then?

Yes, I was using a brush. When I did my greeting cards for Hallmark — I had a lot of these lucky things that happened in my life. Right after high school, I went to college, Kansas City Junior College downtown, and I didn’t have any money. My father couldn’t even pay tuition, so he borrowed the money from the college to pay the tuition so he owed them 25 bucks. But I needed money, so I got a job at Hallmark in the shipping department, shipping out greeting cards. I saw an advertisement for an artist. I applied for it and it turned out to be Hallmark, just upstairs. I went up to apply for it and did an interview, and they said, “Where are you working now?”

I said, “Downstairs in your shipping department!” [Laughter.]

They said, “You know, you can be fired for applying for another job while you’re working with us. Let’s see your work.” So then they began to interview me and they said, “How do you like our cards?”

I said, “They stink! [Laughter.] They’re too sentimental, too sweet. You don’t have anything for men!”

The war was just starting. They said, “Oh, yeah, we’ve got cards for men. We’ve got these little cuddly creatures we call ‘Critters,’ and if it has a pink ribbon it’s for women and if it has a blue ribbon it’s for men.”

And I said, “I wouldn’t send one to my grandmother.” So anyway, they looked at my work. At that time I was using a brush. They hired me.

Mr. Hall, the founder of the company, had his office about 10 feet away from where my desk was. He’d stop by and talk with me every now and then and say, “I have a friend who’s having a birthday. Would you draw me a card?” So I did a lot of cards for him. Original cards.

I worked with the writers, who wrote their “sentiments,” they called them. There’s about four or five of them, everyone in the department, and I would write with them. Every morning we would have a display that would project their sentiments on the wall, and we’d discuss them. Then they’d give them to me, and I’d show them my version of them.

Your versions were cartoon figures.

Yes. This was a brand new thing for the greeting-card business, because up until that time greeting cards were all flowers and sweet pictures and things like that. The only time you ever sent a humorous card was with “Slam Valentines.” They realized that the servicemen need cards, so my attitude about their line of cards was right down the alley with what they wanted. So I began drawing all their cards except the flowers, and I sat there and did cards all day long. Then they sent them over to the art department and they’d try to copy my work, and screw it all up. [Laughs.] Anyway, I think that I was, together with them, instrumental in changing the whole greeting-card business, because now when you buy greeting cards, they’re all humorous! Very seldom do you find a sweet little flowery card.

Where’d you find out about using a brush? That’s a fairly sophisticated drawing tool. Did one of the artists at The Kansas City Star tell you “I draw with a brush” or something?

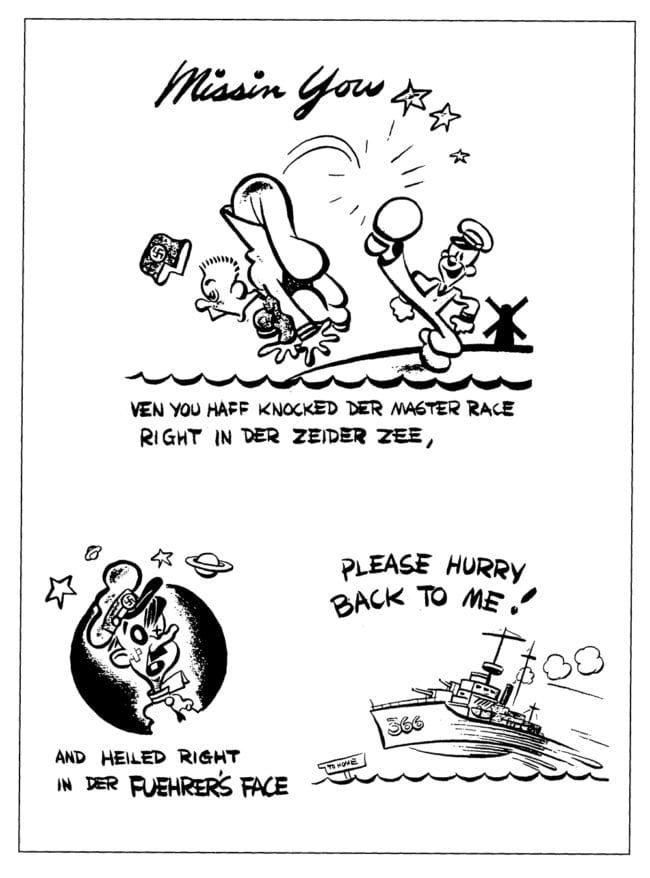

You know, I don’t really know. I think I saw somebody do drawings with a brush and it just appealed to me. You could get wide lines, smooth and silky. So I did that for a while. Even with Beetle Bailey, I did a little bit with the brush, but it didn’t work out. The other big change was after I’d started the strip, as a college strip, and it wasn’t selling well. I was very disappointed. They were thinking about dropping it; we only had about 25 subscribing papers there after six months. The editor of the Philadelphia paper — this was the big turnaround — thought that I should put Beetle in the Army. I was against it because after the war, all the Army strips, like Private Breger and Sad Sack and all of them just went down the hill. Some of them just completely disappeared. I didn’t want that to happen to me, so I resisted putting Beetle in the Army. This Philadelphia editor says, “You’ve got to put them in. They’re drafting guys like Beetle.” So I said OK. Fortunately, I had my four years of the Army experience to fall back on, and all the sketches and drawings and everything like that. I had a big pack of photographs I had saved, so I had research material coming out of my ears. So that was a big turnaround. The minute I put them in the Army, boom! That thing took off. But I was still worried about it, and that’s one of the reasons I started Hi and Lois. To have something to fall back on when Beetle failed.

Oh, I see. [Laughs.] You figured that at the end of the Korean War, he’d be unemployed.

People hated the war, you know? Why would they read about it? And even so, I don’t know how they’ve ever sold the strip around the world to other countries — 52 different countries — with an American Army kind of theme. I found that over in Turkey, they use the strip to make fun of the Turkish army and the Turkish president. [Laughter.]

You were born in 1923 in El Dorado, Kansas. Your father moved around quite a bit, until you landed in Kansas City when you were about 3 years old, is that right?

I was more like 5 when we lived in Kansas City. We were there for the Depression, and my father was an architect. There wasn’t much building going on. But when they would discover oil, like in El Dorado, he would go out there and build the school, the office buildings, homes. He’d get pretty busy. Until he filled up the town. Then he’d move to Amarillo, Texas, then Bartlesville, Okla. So he moved the whole family around with him. In Bartlesville, we had an outhouse. We didn’t have a bathroom. My mother used to bathe us all in a metal tub in the kitchen. [Laughter.]

And then from there you went to Kansas City?

My father decided he had to settle down. He could build churches. So then he specialized in building churches, all over the Midwest. I went back and looked in the books, he could build a church for $6,000. I think the car he bought cost $250. [Laughter.] Times have changed.

When you were growing up, you were looking at newspaper comic strips. What were your favorite strips?

That’s where I learned how to read. My father, on Sunday, would have me go down to the porch and get the paper and bring it back up to bed. And I’d lie there in bed with him and he’d read me the funnies. And his favorite was Moon Mullins. He would laugh until tears came down his cheeks, and I’d laugh with him. So that became my favorite strip. I began to try to draw like that, Frank Willard. I also drew political cartoons. From the time that I was 3, I was drawing. My mother was an illustrator for The Kansas City Journal, which doesn’t exist any more.

That was a weekly, wasn’t it?

Well, eventually it evolved into a weekly. But it was a daily at one time. And when my father would write a poem, let’s say for Thanksgiving or Christmas, my mother would illustrate it, and they would run it on the front page of The Kansas City Star, a great big picture for Christmas or Thanksgiving or Easter or whatever. I’ve got an old scrapbook full of those. She was a very good artist, and so was he. He used to sell his paintings, as well as his poems. He was also a musician. While we did the dishes, he would play the piano. Back in those old days, before you had recordings — discs, and that kind of stuff — people used to go and buy sheet music in stores, and they all learned how to play the piano. My mother played the piano, I played the piano — the whole family played the piano.

You sold your first cartoon when you were 11, but it wasn’t for money. It was just published.

No, it was for a dollar.

Oh, a dollar! [Laughs.] Then, you sold the others?

Well, back in the Depression, we all had to work, everybody in the family. All the kids. I started working when I was 3. My brother would take me selling Liberty magazines from door to door. I’d go with him. He’d say, “You take that side of the street, I’ll take this side of the street.” So I’d go up to a door and ask them if they wanted to buy a magazine. No. I’d go to the next house, and they don’t look like they’re going to buy a magazine either so I say, “That house has a dog, so let’s skip it.” [Laughs.] But I mowed lawns, I did painting, I delivered on my bicycle for the drug store for 10¢ an hour. I caddied — anything I could do to make money. And then when I sold this cartoon for a dollar when I was 11, I said, “Boy, that’s where the real money is!” [Laughter.] So I dropped out of school. They couldn’t get me to go back. I sat there, reading Writer’s Digest, I think it was called. It used to have a list of magazines that bought gag cartoons. I’d send gag cartoons out all over the whole country. I think by the time I was 13, I’d sold about 300.

So you dropped out of school for that period of time. Eventually you went back.

I was out for half a year, so I lost half a year. When I went back to junior high school I was in a separate class. All my friends had moved on to high school, and I was just kind of miserable and quiet and shy. All of a sudden they had a class election, and I was elected vice president of the class! I said, “I didn’t think anybody even knew me!” [Laughs.] This happened to me over and over again. When I got into high school when I’d join a group, like debater’s society, they’d make me president. I’d join the art society, they’d make me president. I joined the YMCA, they made me president. Then a bunch of us got together and said, “You know, there’s no place for kids to do anything in their spare time.” You’d go down to the corner and a cop would come by and say, “You kids break it up, now.” We’d go to a drugstore and sit in the booth and a guy would come over and say, “Listen, you buy some stuff or you get out of here.” And we’d say, “We don’t have any place to go!”

So we decided we would rent the Masonic Hall, and once a month, we would have a dance for kids. So I began running that thing once a month, a parent-sponsored dance. We hired bands, and we’d have contests like during intermission — a nail-pounding contest for girls and a diaper-changing contest for boys. We’d have dance contests — I won one once. And I put on a display, a real wild demonstration. I ran that, and I was officer of my class, I did murals for the home show, which was a big citywide mural show. I won an oil-painting contest from American Magazine. I won an award in a local writing contest, “What would you do if you were mayor of your home town?” The vice principal called me and said, “You’ve got to cut back on what you’re doing; you’re doing too much stuff. We had a kid who had a nervous breakdown because he was trying to do too much stuff. You’ve got to cut down on half of it.” So I had to go out and resign all these different things. I was also an editor on the paper, I was one of the editors of the yearbook, I was the columnist for the paper — I wrote a thing called Snooperman! [Laughter.]

So you were busy!

Oh, yeah. And then I did cartoons for the paper. You had to cut into a chalk plate and they poured zinc onto it and made a plate and printed my cartoons.

I thought they gave up chalk plates long before that.

Well, this was 1930-something.

1937? 1940?

1937, 1938.

I’m trying to remember how that chalk-plate thing worked. You drew on the chalk —

There was a little device with a little point on it, and you’d use it to carve into the chalk coating, making your drawing. Then they would pour the metal over it, and come out with a pretty plate.

OK, so the part of the drawing that you wanted to print is the part you were digging into the chalk.

You’d cut down into the chalk, and there was a black backing under the chalk, so you’d see what you were getting. [Laughter.]

And if you had a twitch while you were doing that, the chalk would chip away and you’d be stuck with gash instead of a line.

I also did photography for the yearbook — a Packard camera, it cost me 50¢ — and I set up a dark room, did all my own photography printing. I also did caricatures of all the prominent people in my class, all the way through the yearbook. I mean, I was busy! [Laughs.]

When did you graduate from high school?

I think it was about 1941.

And that’s when you thought about going to Kansas City Junior College.

I was going to quit school. I’d already done some comic strips and submitted them to the Register Tribune Syndicate in Des Moines. My father used to go up to Iowa, so he took them up there for me. And they were turned down. They looked at me and said, “Oh, a 15-year-old boy!” By that time, I had a weekly comic strip in The Kansas City Journal, called The Lime Juicers, along with the gag cartoons that I was selling. They didn’t pay me for the strips. I did that for about a year.

And that’s while you were in high school?

Yeah.

You and a friend — David Hornaday — tried to sell a comic strip together.

Yeah. We were always doing comic strips, and I made him one of my characters and I drew myself as one of the other characters. [Laughter.]

It seems to me that at one point the two of you went to New York to try to sell one of these. Am I remembering that right?

He didn’t go with me, but he wanted to work on it. It was an adventure strip, In the Wake of the Wanderer. Two guys were on a boat and they were going around the world, having adventures. It was an imitation of Milton Caniff, Terry and the Pirates. I don’t remember exactly what happened to it, but I submitted it to Molly Slott at the Tribune News Syndicate. Everyone was very nice to us. [Laughs.] I got wonderful reception wherever I went. Even to this day, I can’t imagine why everybody was so nice to me. I think I smiled a lot. [Laughter.]

Could be because they saw this really young kid and said, “Look at this guy. He’s actually talented, and he’s standing here like a grownup.” [Laughter.]

And there were several cartoonists who wanted me to be their assistants. They asked me to come work for them. I didn’t want that. Disney sent a guy to Kansas City one time to interview me to work with them. The guy was very knowledgeable; he looked at my work and said, “Yeah, yeah, you’d be great to work at Disney.” Then he asked me how old I was and we talked about my life and everything. He patted me and he says, “I think you ought to finish school.” [Laughter.]

Cont.