Let’s talk briefly about relationships with the syndicate. It seems to me you own Beetle now, don’t you?

Yeah. When I started out, they owned it, and if I died, they would take it over; my family wouldn’t get anything. Then a while back — some years ago, in the 1980s I think — they sent me a contract that stipulated that they owned the strip and I was working for hire.

You’d been doing this for over 30 years and they sent you a contract saying they were the creators?

And I was a work-for-hire [Harvey scoffs indignantly], and they owned the strip. I said, “First of all, it’s a lie. I’m not going to sign the doggone thing.” I wouldn’t sign it. And finally they came back to me and said, “If you sign a new contract with us, we’ll forget about the work-for-hire. But if you sign a new contract with us, we’ll give you a million dollars.”

So I said, “OK.” Fifteen-year contract.

But it wasn’t ownership yet?

I own it. I give them the rights to sell it. Boy, it’s a complete turnaround. I own it and they pay me a bonus on top of it. [Laughs.]

So first, they offered you a contract that said, “We’re the creator and you’re work-for-hire,” and when you wouldn’t sign that, they came back and said, “OK, you can own it, and we’ll give you a million-dollar bonus.”

Yeah, to allow us to distribute it.

Boy, I’ll say turnaround. [Laughter.] How important is ownership? I mean, you talked about how your family has a stake in it, which they’ve had creatively for some time. But, apart from that, how important is ownership?

Well, so many strips, for instance those with characters like Betty Boop and Popeye, the owner can capitalize on it, get 100 percent of all licensing and merchandising and so forth.

Another part of the benefit of ownership, I suppose, psychological as well as financial, is that you get to decide how this character is going to be exploited. And you aren’t as liable to editorial control as you might otherwise be.

Yep. Well, they still occasionally will tell me that I can’t use a certain idea, which rubbed me the wrong way.

The most famous instance in Beetle of the syndicate trying to control it was with the belly buttons. [Laughter.]

That’s true. If I showed a girl in a bathing suit, and I put a little dot for her belly button, they’d whack it out. Too naked I guess. I went down to the syndicate one time, and they showed me a little box full of little black dots. They’d cut the belly buttons out with a razor and put them into this little box. Beetle Bailey’s no-belly-button box. I took that as a challenge. I went home and did a strip in which Cookie gets a big shipment of navel oranges, and then on the crates, I had a bathing beauty with a little dot on it. They finally gave it up. They said, “You win the belly-button battle.”

We talked about the trouble with the feminist movement objecting to Miss Buxley. That objection didn’t come from the syndicate, did it? It was the readership?

Yeah, the syndicate got after me about that. But it started with the feminists. I had a hard time with that. When I was growing up, if a woman walked down the street and men whistled at her, it was a compliment. But feminists decided they didn’t like that. I can see in an office environment that would be uncomfortable for a woman, so I finally agreed with them, and decided I’d go along with them. What I did was I changed Miss Buxley’s whole character, personality. Before that, she was a sex object, but when she started talking, she was no longer an “object” — she was a person.

I noticed the other day that Beetle is dating Miss Buxley. I guess I never recognized that was going on until a couple weeks ago and the two of them were obviously out on a date together.

Oh yeah. They go out on a date and they go sit under trees and look at the stars and everything like that. I never have them engage in sex though. No kissing yet, either.

Somewhere I read that the 52 countries in which Beetle appears do not include France or England. Is that still true?

That’s right.

Why do you suppose that is?

I did go to France one time and I asked them. And they said, “We Frenchmen, we do not like war.” [Harvey laughs.] I couldn’t convince them that I don’t like war either. Neither does Beetle. We’re just drawing about the peacetime Army.

You talked about Sylvan Byck and how significant he was in your career and development and so on. What about some of the other people that you must have worked with at King? Like Ward Green. Did you have much to do with Ward Green?

Yeah. But not as much as with Sylvan. But then, later on when Sylvan quit, they asked me if I knew anybody who could take over the editorship, and Bill Yates was an old childhood friend of mine. [Harvey laughs.] When he came to New York, I gave him my job at Dell Publishing Company. I sort of helped him a little bit. He had several strips that he worked on, and we worked together; we were golfing buddies and everything like that. He had been editor at the Texas Longhorn, you know, the college magazine, at the same time as I was editor of ShowMe, and we used to correspond as kids. He entered a lot of the same magazine contests that I did — Open Road for Boys and magazines like that — so we had corresponded, as young, 12-year-old, 15-year-old kids. [Harvey chuckles.] So we go way back.

When he came to New York, he wanted to know if there were any jobs: I said, “You can have mine.”[Laughter.] So he took over my job at Dell Publishing Company with the 1000 Jokes magazine, and then he took over Sylvan Byck’s job. When he decided to quit and work on his own strip, Jay Kennedy came in. I worked with Jay for a long time. The new one, Brendan Burford, very nice young man. So I had some good editors there to work with.

Do you have much contact with them these days? I would assume that by now they really are willing to let you do whatever you want to do, pretty much.

I don’t have as much contact with the syndicate as I used to. I used to go in and once or twice a week and have lunch with someone. I’d go down to see Bill Yates. But, somehow, I just don’t have the time or the inclination to do that any more. They moved into new offices about two years ago, and I’ve never seen it. I keep waiting for someone to invite me down for lunch. [Laughter.]

Editing the 1000 Jokes and the other things you did at Dell, there was writing involved as well as selecting cartoons.

I wrote a lot of the articles and captions and things like that. I didn’t have a staff, you know. I had to do it.

And sometimes you’d buy a cartoon, but you’d change the caption?

Yes, I also edited the things. I was actively involved as an editor. Editors do those things. [Laughter.] We designed the covers, I wrote a lot of the articles, I actually did some of the drawing, and created features for it. Because when I took over the magazine, the guy Ted Shane, who had been the editor, he would just print a whole book full of jokes — I don’t know where he got them — in 1000 Jokes magazine. And he would buy occasional cartoons. But when I took over, I said, “I’m going to make this with as many cartoons as I can buy.” I had a lot of my friends submit work to me. I enjoyed that. I paid $10. [Laughter.]

But then, when it came to doing the other magazines, like Family Album, I think I wrote most of that. Usually, they would give me a picture of a Hollywood family with their kids, and I’d write this complete work of fiction, about how they went on picnics and they took them here and there, and how they loved them and took care of them, dressed them up. It was all fiction. Then we had Film Fun, which was almost like a sex magazine, with bathing-beauty movie stars. I would just print their pictures, and then I’d write the caption, like this girl is showing off her legs and everything. I’d write, “The Thigh is the Limit.” [Harvey laughs.] Captions like that.

And at the same time as you were doing that, you were also freelancing cartoons.

Yeah, sure, all the time. In fact, when I took the job, I said, “Only if I get Wednesdays off, because that’s when I sell my cartoons.” But I was still in the lower bracket of income, because after we got married, I didn’t want to live in this condemned building with my new wife. So I bought a house, over in New Jersey. The house was, I think, $11,000. They didn’t want to sell it to me, because my income wasn’t high enough. The real-estate broker vouched for me, and signed some kind of affidavit. They were impressed by my ability to sell gag cartoons and everything, and they said, “Oh, you’re the cartoonist that does these cartoons for Saturday Evening Post?” So anyway, the real-estate agent vouched for me, and they allowed me to buy the house. That’s how far down the rung I was.

Can we talk a little about NCS, the National Cartoonists Society? When did you first hear about NCS and decide, “Oh, maybe this is an outfit I ought to be engaged in”?

I guess it was when I was selling gag cartoons. King Features had a cartoonist by the name of McGowan Miller, and he worked in the bullpen. He was a member of NCS, and he invited me to come with him to a meeting. The Society at that time consisted of just a few guys. I remember McGowan Miller belonged to a college club or some such thing. They had a nice bar. My first meeting, we just went to this bar, and the guys sat around by the bar and had drinks and told stories. Eventually, they invited me to be on the board. Walt Kelly was president [1954-56], and a board meeting was pretty much that the guys would get together and start telling jokes and stories. I was on the board until they asked me to be president. I think I was about 26 years old or something like that.

One day I was feeding one of my little babies and the phone rang and it was Milton Caniff. He said, “Morton, we’re just having a meeting down here. We want you to be president of the group. Make sure our attendance improves.”

I said, “Oh boy, I don’t know if I can handle that. You know, I’m doing my comic strip all by myself, and I’ve got a comic book that I’m doing. I’ve got all these little babies that I’m feeding, doing all the shopping. My wife doesn’t drive” — so I had to take her everywhere, to the shop — everywhere. I said, “I don’t know if I can handle it.”

He said, “Well, here’s Rube.”

Rube Goldberg got on the phone, “Mort, we want you to be our next president.”

I said, “Gee, I dunno, I just told Milton I don’t think I can — “

“No, we want you to be president. Here — here’s Walt.”

And Walt Kelly comes on and finally I gave in.

I became the youngest president NCS ever had. Then, after I became president, that’s when all the barbs started. Russell Patterson got up and said, “This is the worst administration we’ve ever had!” I was standing right there next to him, you know, and hearing myself belittled. like that. That’s because he would come in and he wouldn’t wear a name tag. I had expanded the society because it started, when I got in there were only about 30 guys, I said, “Well, wait a minute, there’s a lot of cartoonists …”

I was president in 1959-60. We’d meet in a bar somewhere, and then there’d be about 10 or 15 of us, as I said, and that would be our meeting. And then when I got in as president, I had an agenda printed for the meeting, and I had things I wanted to accomplish, things I wanted to do, and they kinda resented that.

I was the president of all these old guys, Milton Caniff, he was not that old, but Rube Goldberg was I think in his 80s at that time, or maybe almost 90. He was around for a long time. When he gave up cartooning and went into sculpture, his wife said, “That keeps him alive, because he gets up so excited every morning to get over to the sculpture studio and do a sculpture.”

Did you have much to do with Walt Kelly? Did you spend any time with him?

Yeah, he and I never got along too well. He was OK. I took a trip out to Chicago once to do a show with Milt Caniff, and Gus Edson, maybe, and Walt Kelly. We took the red-carpet train from Grand Central all the way to Chicago, and the minute they got on, they went and sat in the club car and started telling jokes and drinking. I didn’t participate in that the way they did, because they were really getting soused up and I didn’t like that then. Finally, when we got to Chicago, they all took off in different directions. They had girlfriends, and I was left all by myself. And Milton said, “Where are you going? Do you have a syndicate friend or anything that you’re going to?”

And I said, “No. I thought we were all going to stay together, I thought we’re gonna put on a show.”

So he says, “Oh, come on.” He took me to his syndicate, which was the Sun-Times, and he said, “Mort here didn’t have any place to go, so is it OK if I bring him along?”

But those other guys, they just had their own agenda. Several times when I went off with them, to Georgia one time, and New York, they just left me behind. Very often I was left in the lurch while they went off to find a girl. [Harvey laughs.] But I didn’t do that. I tried to be faithful to my wife and kids and everything like that.

Did you know Willard Mullin? You must have known him. He was in his glory days.

He was a great sports cartoonist, probably the best ever. He was good. I knew them all. God, I was so impressed with these guys when I came to New York. As a life-long fan, it’s like going to Hollywood and all the stars take me in. They were sooo nice to me, I couldn’t believe it. They all had time for me. Except for when we went on trips [laughs].

Yeah, right. Then they took their time on their own.

Caniff, he always took work with him, I think. Once we went to Dallas for some meeting, I forget exactly what it was. It wasn’t NCS but it was Comics Council or some other organization we belonged to. We had a lot of organizations back in those days. There was a big gathering, and Milton was up in his room most of the time drawing, working. Then he came down for a while, and all of sudden, he got sick and they took him to the hospital. And when he was in the hospital, he asked us to bring his work over so he could work while he was in the hospital bed. He would never stop working.

Maybe we can shift gears to the museum. It took over 30 years of your life. How did it get started?

Well, I’d always had the dream. Why aren’t there any cartoon museums? There are other art museums — the Museum of Modern Art, some of the junk they display. And there were several people like Jerry Robinson, who would stage exhibits of cartoon art. NCS did some — once at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and it was so popular, that I think the museum people got mad about it, because they’re into real art, and people were coming to see cartoon art and just jamming into the couple of rooms they gave us. And I thought, “Why isn’t there a cartoon museum? I think cartoons are the world’s most popular art. Why aren’t there any museums?”

So I went out there, all by myself, to try to get one started. I went to all kinds of places, like the School of Visual Arts — I thought that maybe they had a room or something like that they could devote to it, or I could do something nearby. I found a beautiful building one time that was $500,000. It had been an embassy at one time, and I really wanted to buy that thing and make it into a museum. I tried to get money from IBM and Reader’s Digest and other places where I thought I could get some money. I never could get it. Then Art Wood was trying to start the same thing in Washington D.C., so I went down there and spent a lot of time, going from place to place, other museums. There was a monastery that the church was decommissioning, and we went through there, that would have been a great place.

The Stars and Stripes headquarters there finally agreed to let us use their lobby. And right in the middle of making all the preparations for it came the race riots, and they were especially a target, for some reason. I don’t know why. Anyway, they closed the doors: they wouldn’t let the public in. You can’t have a museum when the public’s not invited. So, we gave that up, we went to the Kennedy Center: We tried everything and came home discouraged.

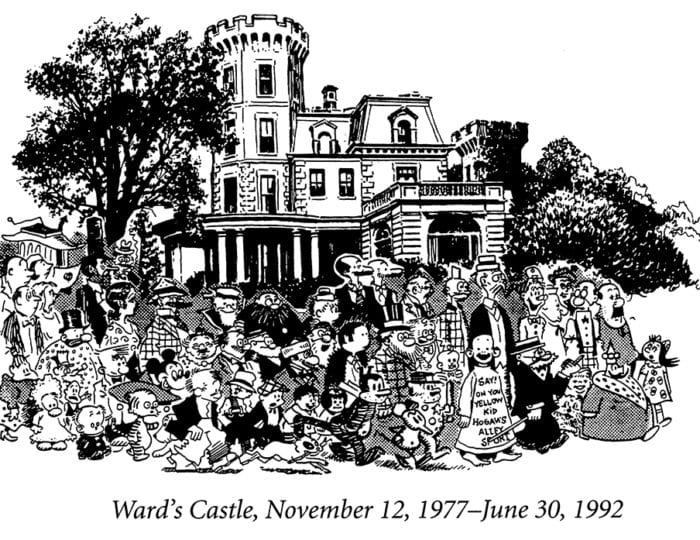

There was a big mansion in my neighborhood in Greenwich that the descendants couldn’t afford to take care of. And the owner said to me one time, “I wish somebody would come along and start a museum in that place.”

And I said, “Boy, you’ve got your guy.”

So, I went and got permission from the town to do it, and my son Brian, who had just graduated from college, had a lot of artistic friends, and they came in and they really refurbished the place. They painted it. They put in galleries. They just did everything, fixing it all up and getting it running, because nobody had been in it. The toilets didn’t work and things like that. Then I got Jack Tippit and his wife to help. He was a cartoonist who had some experience in the military: He was an Air Force officer, and I guess he had been president of the National Cartoonists Society, influential, so he came in as the director.

And we opened the thing up and we just did marvelously. We had school groups come to visit all the time, and we thought we were a tremendous success. Only a block from the railroad station, it was right on the Sound in Greenwich, surrounded by beautiful homes. There was a restaurant next door. So we thought we were perfect. Then after a while, the owner came to me and said, “You’re wearing out my place: too many people coming.” [Harvey laughs.]

I said, “I didn’t open a warehouse, I mean this is a museum. I want people to come, I want more people coming.”

He came back about a month later and he said, “I could get more rent than you guys are paying. I’m not going to renew your lease.”

So, we had to move out. We decided we had to find a new place. When I announced it to the staff, that we had lost our lease, our whole staff, everybody, cried. You could see big tears, because they loved it, and it was so successful, and to be treated this way.

So we looked all over Westchester, and there are a lot of castles in this area, because people that came over from the old country and made money, they wanted to be kings, you know? So they built themselves castles, turrets and battlements. Finally, Greg’s wife said, “I remember there was a big castle down the road from us, up on the hill.”

It was a beautiful concrete castle. The guy who built it was a manufacturer: Down on the river below, he had had a factory, and he had created the method of reinforced concrete, putting rods and steel mesh inside the concrete. He had built the base of the Statue of Liberty, and the Holland Tunnel, things like that. The surviving descendant was living at the Westchester Country Club. We got her over there and wined and dined her and said what we were going to do. She thought it was a great idea. So we bought the whole goddamned place for $70,000.

Anyway, so we got Brian’s friends again to come and help fix it up. Then we had a regular construction crew do the big, tall, dangerous jobs. We put a steel strap around the five-story turret, so it would keep that from falling apart. One of the guys fell of the ladder and died, killed in the reconstruction.

There was a decorative frieze around the top of the walls in the rooms, and one of Brian’s friends, who was a sculptor, came in and recast them and glued them back up again. There was ice on the dining-room floor, so we had to patch that up, get the toilets working, and so on. Anyway, it took almost a year, and we finally got it. And we opened it up, and the night that I went down to our opening party, I was driving on the river. And up on the hill, we had spotlights beamed at the tower. And I tell you, my heart beat, I was so happy and proud of it.

We were there 15 years, we did great exhibitions. We did a Milton Caniff exhibit, Peanuts exhibit. Batman exhibit — all kinds of stuff. We also had a caretaker’s cottage, so we had a guy living out there who took care of the place. Anyway, we were just very, very happy with that place. My wife Cathy was then executive director of the Newspaper Features Council, and we had the fourth-floor office for her. She’d been looking around for an office, and I said, “We’ve got the fourth floor; nobody’s using that place.”

She was sitting there working one day, this is after we’d been there for 15 years, and heard this loud thud, and the crenelation from the top of the tower was cracking off. Boy, we thought, somebody could get killed, because that concrete falling four stories down could do some serious harm.

We used to go up on the tower, and you could see all the skyscrapers in Manhattan; we’d look up the other way, and we’d see all the way up to Yale University. We could see far out into the Sound down below, all the houses. It was a beautiful place.

We called in an engineer and he said, “It’s going to cost you at least a million dollars to fix this place up.” He said, “This is a big job.”

And of course, we didn’t have a million dollars. We decided we had to move again, and we began looking around, again. It was like starting all over. They heard about us down in Palm Beach, Florida, and they had a group up here in New York, a firm that was looking for attractions to move to Florida. They said, “When it rains, and you can’t go to the beach, what do you do in Florida?” Go to a museum.

So we went down there and they showed us all kinds of sites until we got to this brand-new, beautiful, new shopping center that was being built. It was an outdoor shopping center. It had a fountain for a centerpiece, and it had restaurants all around it, and at the end of it, it was only about four blocks long, but the end of it was an acre that had been reserved for something like us. So we took that.

I designed the building, using all of Addison Mizner gimmicks to build the archways and the towers and everything for the museum, it was a 52,000-square-foot building, three stories, and it was magnificent. Bill Janocha did friezes that were all cartoon characters that went around it, all the way around the building. When we moved in there, we had a photographer taking pictures of people entering the building. Cathy and I were the first ones in, and Cathy started crying. [Laughter.] She was so happy.

You told me about some kid who wrote a letter about the design of the building.

Yeah, after we’d had our opening and everything like that, this kid, a 15-year-old boy wrote in, “This building is a monstrosity. It has every gimcrack and gimmick that Addison Miznir ever did, all in one building. It’s a caricature of Addison Miznir.”

I thought, “Boy, what a smart kid.” [Laughter.] He’d gone down to the library and gotten out all the books on Addison Mizner and I’d copied everything from him.

And you were looking for a caricature of a building. I mean, that’s what you wanted.

Yeah, right! Well, originally, the architects just gave me a square white building. It looked like Macy’s or Wal-Mart. And I thought, “Wait a minute. We have to get dramatic here. So that’s when I designed it myself. And I was on that site every day working on improving the quality of it.

Then the people who pledged money to support it started caving in. Marvel had pledged, what, a million dollars?

Yep, a million dollars. Then they gave us $100,000. I don’t know how they ever went bankrupt when they’re making Spider-Man movies.

When they went bankrupt, it was before they got into the movie business.

Yeah, they got into the toy business and various other things. We tried to do a lot of licensing and all kinds of money-making gimmicks. We had credit cards, which we still have. I have one. Whatever people use them to buy, we get a percentage back. And one of the things we had was a candy company. We designed packages for them, using our cartoon characters. They really liked that idea. “Boy, we’re gonna sell millions!” So we had a contract — and I still have it — guaranteeing us $500,000 a year. And it was for five years. They said, “You’re going to make at least two to three times that amount of money. This is an upfront guarantee.”

They went bankrupt. The two owners got in a fight, locked each other out, took each other to court. You can never imagine anything like that happening: Give up the profitability, the business. But, they did it. So all of a sudden, we had no source of income to run the darn place except daily admissions, which weren’t, yet, enough. Of course the minute anything starts to go sour, you sour the whole opportunity for anybody else to get any money. The bank foreclosed on us immediately. We still owe them a million dollars for the construction. Then you go to the city, or anyplace else to help out, and they said, “It looks like you’re in trouble.”

So everybody deserts the ship.

Sure. Then we tried to bring in tenants for the second and third floors that we could rent out. We tried to bring in different people, different organizations — theater, a miniatures museum, a Holocaust museum, two universities for computer classrooms and things like that. We brought over 30 different organizations to the city; the city turned them all down.

The city had to approve, and they turned them all down.

Right. They had certain problems because when they built the building, they got a tax exemption for 15 years, or some such thing. But the tax exemption said that they could only have something like 10-15 percent of the area as profit-making; everything else had to be non-profit. That’s why we brought all those museums and universities in. But even though they were tax-exempt, the city wouldn’t approve them.

And yet the city wanted you to come down there. They gave you the land for a dollar, or something like that.

And then later on, somebody says that they had heard that the city wanted to take it over. We built the building and paid for it — $7 million dollars, it cost us — and they wanted to take it over and run it themselves. They were trying to force us out, make us give up. Then when we tried to sell it, we went through hell again. Finally, we threatened to sue them. There was somebody from some foreign country who wanted to buy it.

So they wanted to force the museum out of the building so that they could have the building.

I guess so; that’s what somebody told us. Which is a real dirty trick, because they begged us to come down here to start with. I couldn’t figure it all out. The building is still empty today. The owner is building an addition over the parking lot, building higher and making a more complex place out of it. But it’s not open yet. Say they’re supposed to have a bookstore there. I knew the owner of the bookstore who originally had a bookstore there, and they invited him to come back. I’ve been talking to him for about four years, and he’s not back yet. [Laughs.]

Here’s a sort of a nuts-and-bolts question — do you have something like a daily routine, or a weekly routine? You have monthly meetings to make gag selections. Are there any other routines?

I have a regular routine. I start on Monday morning to do a week’s drawing. And when I finish that I start doing gags for the next gag conference. Then Tuesday’s my golf day. Usually by Friday I’ve got a lot of stuff. During the week, I work on other projects. I’ve got The Best of Times, the magazine I told you about, and I work on that. We have a new website going up called cartoon.org, which used to be owned by the museum. They weren’t using it any more, because Ohio State has their own website. So we took that over and are building it up as a store for Beetle Bailey comics, selling my originals, stuff like that. As you saw looking through my warehouse, I have 80,000 pencil drawings up there and 58 years of original cartoons. I tried to give some of my originals away to the museum. Many years ago I gave some to Santa Cruz University, and I took a $50-a-piece price on my originals.

And you took it as a tax deduction on income?

It was a tax deduction. A couple years later the government came back and just swallowed it. They said, “These are worthless. Once they’re printed, who wants to see it?”

I said, “Well, have you ever seen a picture of the Mona Lisa?”

They said, “Yeah.”

I said, “Why do they save the original?”

“Well, I don’t know.”

We went to court up in Bridgeport with a jury and a judge, and Milton Caniff came and testified for me, and all the other big cartoonists came and testified that they had sold their originals and their originals are worth money. Then they would read some of my gags, and the jury was laughing and just having the best time. I said, “There’s more to it than just the artwork; there’s the writing! These are valuable pieces.”

But there was one guy on the jury who kept looking at me angrily. You’ll always find the dissident. Anyway, I don’t know exactly what they call it; it wasn’t a hung jury, but it was similar. The judge had to make a decision. They allowed me half of the deduction. So instead of allowing $50 each, I think it was $28. The judge afterwards says to me, “Hey, this is the best trial I ever had. Much more fun.” [Laughter.] They changed the law after that.

When Johnson was retiring from his presidency, he was going to give all of his letters and things like that to the Johnson Museum. They were telling me, “This is like your case. You sit there and do a drawing, and you take a tax deduction, do another drawing and take a tax deduction. It was like you were drawing money. Do it all night long if you wanted to.” They had a point: Is there a market for it? Does anybody buy it? So anyway, they were trying to pass a law to catch Johnson. The outcome is that an artist can’t give away his work to a museum any more and take a tax deduction if it’s his own work.

And I do probably ten drawings a week for charity and auctions. They write me back and say, “Well, your piece went for $150-200.” I’ve been at some of these auctions myself. Soup kitchens where they feed poor people, help them find jobs, give them advice and stuff like that. I give to them every year, and they invited me down and made me a guest speaker one year. I think one of my drawings, which took me about 15 minutes, sold for about $1,500.

Well, the final irony in that is that you can’t take a tax deduction for donating your drawings even if they’re appraised at a particular monetary value, but when you die, whoever inherits your estate is going to be taxed on the value of those drawings. So the government gets to collect estate taxes on your drawings based on some value or another, but you don’t get the advantage of that. That’s astounding. So you get your reward elsewhere.

Yeah. I do a lot of presentations before groups. And I go up on stage, and maybe the audience is talking and not so interested, but as you begin to draw it’s like magic. “Oh! He’s drawing Beetle Bailey! Oh, look at that!” By the time I’m through, there’s big applause. You start out with a blank piece of paper, and all of a sudden you’ve got this drawing. I think that’s the way I feel about writing gags. I’m sitting there with a blank piece of paper, I’m thinking of a gag, and I like it very much and I draw it up. That wasn’t there just 10 minutes ago. People are going to be reading that thing maybe for 58 years. [Laughter.] Or they’ll be tacking it up on bulletin boards, telling somebody about it, and that’s the thrill of it. This didn’t exist before; now it exists. I’m creating new things every day. It’s fun. I get the biggest kick out of creating gags. It’s one of the things that keeps me working. I’m over 85 and I’m still working, because I get a big kick out of it. I can’t wait to draw it up. I had an idea recently for a strip — I get ideas for strips all the time. I’ve probably got a dozen in there right now. One that might amuse you, actually, is called Chasing Ostrich. It’s about a pretty young girl and a nice-looking young man, and they’re primarily in New York, trying to get jobs as actors either in the movies or on stage. It just shows their travails and experiences. They live together, even though they’re not married.

But they keep running into celebrities when they go for jobs — they run into Oprah, and they ask her how much money she has. She disappears and they say, “You shouldn’t have done that. She went home to count it.” [Laughter.] I thought I could work in celebrities, caricatures of them. I’d have a lot of fun with it. I tried several cartoonists about it. They were interested, and they come by the studio and I talk to them. But I never got anything out of it.

There’s a market out there for comic strips, but the newspaper is sort of collapsing. A couple years ago Editor & Publisher did a couple pieces about newspapers that wanted syndicates to reduce their fees.

Oh yeah, all the time. I get those monthly statements of how they reduce the fees.

And they keep reducing them?

Yeah. They were upping them in the old days. About once a year, they’d up them 50¢ or so. They’d just keep escalating until some of the papers were paying quite a bit of money. I think The New York Daily News was paying $500 a week or something like that. That was a lot. But they’re all coming down now. Not only that, but the syndicates aren’t taking on new strips any more. There’s just not a market for it. Papers are cutting down on the number of strips, and canceling strips right and left.

I’ve had a few cancellations, but actually Hi and Lois has gained some papers from last year, and Beetle has lost a few. I’ve got such a wider group to contend with. I think I’ve got about twice as many Beetle customers as Hi and Lois does. What’s reassuring is that a couple reports from the papers said, “We’re cutting down on all the strips except the ones we must have, like Beetle and Blondie.” [Laughter.] So I’m glad to be in the “must haves” category.

So your sense is that newspapers are cutting back on the number of strips they publish?

Yes. The Daily News used to have four pages of comics every day; now they have three. [And they just, as of January 2009, cut it to two.] I think the comic sections, the Sunday sections, are being cut down too.

When I was a kid growing up in Denver, The Denver Post’s comic section was published as two sections. I bet they had probably 16 pages of comics. Now they have four.

It used to be considered a real circulation-builder. When they would display The Daily News on the stands — you know, where you put money and get the paper out — they always wrapped the whole paper in the comics section. The comics section was the “cover” for the paper on Sundays. They tried for a while to do it the other way and have the comics on the inside, and the circulation went down. It was the comics section that really sold The Daily News. But editors are always jealous of that space and its cost. They were always trying to downgrade the comics section. I keep saying, “Y’know, it’s the most popular and the best-read part of your newspaper! Why would you downgrade it? You should upgrade it!” But they don’t like to hear that.

It’s a distressing time for newspapers.

I’ve always thought, right from the beginning, about the importance of comics in people’s minds. I always call comics the world’s favorite art. From the little kids right to the adults. They all love the comic strips. You ask a little kid about the Mona Lisa and they say, “Who?” But comics are widely read by all ages, all types of people. But nobody will admit it. They don’t go around saying, “I read the comics! I have a Ph.D.!” [Laughter.] You don’t go around bragging that you read the comics. If you took a course in classical art, that means you’re intelligent or that you have taste. But it doesn’t enhance your status with anybody to say that you read comic strips. It’s a constant fight that I’ve had all the way through, being a cartoonist.

I’ve always thought that editorial cartoonists have a greater social status than comic-strip cartoonists, because they do “serious” work.

Oh yeah. Even among cartoonists. I’ve gotten the snub from editorial cartoonists. [Laughter.] We began to bring them into the National Cartoonists Society, and when they’d come to our meetings — I remember this one guy who came up with his wife, shook my hand and said hi, and told me his name. He said, “Do you know who I am?”

I said, “I’m sorry, no.”

He turned to his wife and said, “See?” And he turned and walked away! [Laughs.] Because in his town, he was a big shot. Everybody knew him. He drew about local politics. He was the king of the heap in his home town. They were just so hurt that we didn’t know all of them. So they pulled away and formed their own society. [The Association of American Editorial Cartoonists was founded in 1957.] They just don’t seem to want to have anything to do with the National Cartoonists Society.

Well, some of them do.

Yeah, a few of them. But even The New Yorker cartoonists feel that way. They feel it’s beneath them to associate with comic-strip artists.

Is that right?

Oh yes, yes. Chuck Saxon, who was a friend of mine for years when I first came to New York, wouldn’t join the National Cartoonists Society. I told him, “You know, we’re all going to vote for you for the Reuben this year [1980].” And then he joined. [Laughs.]

New Yorker cartoonists are … I don’t know … a little effete sometimes.

Well, they feel like they’re superior. Most of them don’t associate with us, even around here socially. Lee Lorenz lives around here, and we tried to include him in a lot of our stuff. He doesn’t respond.

How do you think the comic-strip world has changed in the 58 years you’ve been doing it?

Well, I think it was a kind of a fantasy world in the beginning. It’s hard to say. I know story strips were more important for a while. Dick Tracy, Little Orphan Annie, Steve Canyon — that was the most popular thing for a long, long time. Probably the gag-a-day weren’t very numerous. Some had continuing stories. I think when I started, I wanted to go back to gag-a-day. Every once in a while, I would do a short sequence of Beetle with the whole crew. I think Schulz oftentimes had themes that went on for a week. But I think everything’s gag-a-day pretty much now. I may have started like that — I did it without thinking; that’s just what I wanted to do.

A lot of people say that comic strips are “edgier” now. The humor is more risqué sometimes — not necessarily in a sexual way, although that too — but also the language that’s permitted in the funnies and the kind of political comment that you’ll find. You might very well find Dagwood saying something with a political implication these days. We’ve talked about how Beetle has, too.

The political thing is going on. Walt Kelly and a lot of the other ones, they used to exploit themes like that. And then of course, Garry Trudeau started out with risqué stuff, drugs and reprehensible things. And he’s still doing that. He’s doing it right now; he’s doing the story about a guy who’s sort out of his mind, coming back from the war. All befuddled about what he’s doing there. Trudeau’s done a lot of rebel-type things. He’s always getting in trouble for it, too. [Laughs.] People reprimanding him for it.

I didn’t want that. I only wanted to do a friendly strip where everybody would like the characters and have no objections. I got rid of all the sexist material, because it was causing me a lot of trouble.

I saw one the other day where somebody farted. That seems to be acceptable now.

Yes, right. Wiley Miller, in Non Sequitur one time, had a guy looking at a store and the name of it was “Old Farts Clothing Store,” or something like that. [Laughs.] Language like that has been coming in.

To me, that’s always been so distasteful. Like in Blazing Saddles. Who wants to hear guys farting? [Laughter.] I don’t think it’s funny. I did when I was a teenager, but now I look back on it and I say, “That’s so tasteless.”

But there are a lot of areas that used to be completely taboo, and now are accepted. A radio talk show called me, and they had me and a couple other people on. The other people were syndicated cartoonists. We were talking about how there’s a wave of “edgy” comic strips coming out. And then I said, “Well, wait a minute. The strips with the biggest circulations are Beetle Bailey, Hi and Lois, Garfield, Peanuts and Blondie …”

And Zits.

Out of the top 20 strips, there are maybe four or five — like Doonesbury — who deal with more topical, political kinds of humor. Most of the most widely circulated comic strips are still uncontroversial, not edgy.

I avoided controversy or distasteful stuff. You don’t have to have it; nobody even notices that you don’t have it. Nobody ever writes me and says, “How come nobody farts in your strip?” [Laughter.]

Do you have a theory about humor or the comic strip? I know you do because I’ve read you talking about it before. But could you could tell us about it.

You know, I have to stop and think. Do I or do I not? As I said, I like to have my universe with some action in it, some funny pictures. I try to avoid puns because they don’t translate. I’m in 52 countries and if the dialogue in a strip is based on a pun, it’s not going to translate. You’re lost. I’ve noticed a lot of guys do that — the whole joke is a pun, or a mistaken translation of the word, or something like that. So I try to stay away from that, and have it based on some kind of an activity or a premise that can translate. There, again, I’m just looking for safe material all the time. People like that all over the world. Funny pictures. There’s just no getting away from it; that’s the way to do that. I keep telling everybody who writes gags, “More funny pictures, guys!”

They sort of fight me on it. “You know, talking heads can be funny too.”

I say, “It’s got to be awfully funny.” So I take their talking heads all the time and turn it into a funny picture. That’s my responsibility.

What do you see for the future of comic strips?

I think that there will always be a place for newspapers. Maybe not three or four newspapers in one city, but I don’t see any substitute for the local high school’s football team scores, or what’s going on at the church, or what the theaters are playing. I just don’t think you can supply all that information over the Internet. I like to sit there with my newspaper in the morning, take it to the bathroom with me, come back and have my coffee, and skip what I don’t want to read about. I always read the paper with my scissors. I almost always find something to cut out. I don’t think the Internet is going to be the same. I think people are going to always come back to newspapers. Maybe it’s not going to be as big a circulation as they’ve had, but I think we’ll always need newspapers. At least I do. I’ve tried the Internet, but I just can’t find where it supplies the same information I want.

Right now, we’re confronting several crisis situations at various newspapers. The Tribune Media Company — which owns The Los Angeles Times and The Baltimore Sun and half a dozen other papers and TV stations as well as the Chicago Tribune — filed for bankruptcy protection. In my hometown, The Rocky Mountain News announced that it’s up for sale. If they don’t sell it by the middle of January, the Scripps people say they’re going to close the paper. In Seattle, Hearst has put the Post-Intelligencer up for sale.

They’re listening to their stockbrokers. Stockbrokers aren’t making enough money.

And the Detroit papers are going to three-day-a-week home delivery. They’re not going to deliver newspapers seven days a week any more.

I’m thinking I’m getting my revenge from The Chicago Tribune and The Los Angeles Times, because they both dropped Beetle. And they did it on the premise that it wasn’t any good any more. When they dropped Beetle, they tried to fool the public by saying it was a “test drop.” But then the guy went out to Las Vegas and made a speech, the editor of the features department, and somebody asked him about it and he said, “No, we dropped it. It’s never coming back. That was just a sham we told everyone to fool them.” Then everyone voted on bringing it back — I know they voted because Carl Nelson, who has been helping me out on these things, said he had about 7,000 people on his list who told him they wrote in, so I know they did — I wrote to the editor at the Tribune and I said, “If you lie on the comics page, does that mean you lie on the front page of your newspaper too?” Because they’re lying to their readers. So I like to think that since they dropped Beetle, their circulation went down. [Laughter.] I write this every now and again to an editor, I say, “Beetle, according to the readership polls, is one of the most popular strips in the newspaper. Why do you drop your most popular feature? Drop something else. You’re only degrading your newspaper by dropping popular features, since those are the things that keep your readers coming back.” They don’t operate very wisely sometimes.

I agree. Of course, I have a bias that’s the same as your bias. I go to the funnies first, and I go with a pair of scissors in my hand too. I clip out the ones I really like.

That’s always been one of the things I say in speeches. “I’m not after the Pulitzer Prize — I’m after the bulletin-board prize.” That’s where I want my strips to appear. I want people to tape them to the cash register, put them on the bulletin board, cut them out and send them to their friends. That’s what I’m after.

I had a friend who was on the board of The Los Angeles Times. I think he was the only male on the board, and there were four women or something like that. One of them was Nancy Tew; she was the comics editor. They announced that they wanted to drop Beetle. And this friend of mine says, “Just a minute.” He went to his files and he came back and said, “Here’s our survey. It’s the best-read comic in the paper. And you’re going to drop it?”

They said, “Oh, I guess we can’t.” So they kept it on for another year or so, and eventually dropped it. Tew, I understand, was fired and went on to another newspaper.

I think that newspapers are going to experience a renaissance, or rebirth of some sort in the next few years.

I think it’s going to be more like reorganization or a redesign. Even if it’s just a bulletin, or something like that, they’re still going to exist. They almost have to. I think that comics are going to help them.

And if the newspaper is going to survive, comics will survive too.

I hope so. There might be some papers that cut them out, thinking that they aren’t necessary, that they don’t have to appeal to people any more, that people just have to have certain information. But things change all over the country. When I grew up, everybody communicated by telegram. Nobody on our block had a telephone. Then they came in, and one person on the block had a telephone. He’d run up the street and say, “You’ve got a call!” [Laughter.] My grandfather was a telegraph operator. He was almost like a celebrity in the neighborhood. He’d walk down the street and had a vest on with a big yellow chain across the front, and he’d walk around proudly. He had a nice big house and everything. He was the first one that had a radio. But he would put the earphones on and go in the corner, and we never got to enjoy it.

There’s a cartoonist, Ted Rall, who’s now, at the moment, president of the Editorial Cartoonist’s Association, and he also writes a column once a week. He says that advertisers, who right now are advertising on the Internet in connection with newspaper websites, are going to discover that they’re not getting any business off their Web ads. Rall says that people who go to a newspaper website aren’t turning the pages in a paper and finding an ad for something they didn’t know they wanted, or maybe they weren’t even looking for at the moment but now they want it. They don’t read a website that way. They go to a website and say, “I want to know about Obama’s latest appointment.” So they do a search, and it comes up with a story about Obama, and they read that and go away.

Advertising on the websites I use makes me angry. I’m trying to read something, and they pop an ad up there. I’ve got to go up to the X and eliminate it. I don’t even look to see what it’s about. It’s just irritating when I’m reading.

The funnies section is one of the newspaper’s biggest single expenses. If they wanted to cut a big hunk of their budget every year, they could drop the comics section and they’d save a lot of money.

They’d have to fill it in with something else, though. You have a bunch of people in the newspaper office sitting there, collecting their money once a week. Half the time they’re not doing anything. Syndicated material is cheaper than hiring somebody and paying benefits. If you can buy a daily column — you know, $10 a day — that’s a lot cheaper than hiring somebody to sit there and do the writing. I would think that syndicates would be well off, although they’re fading too. The Tribune Syndicate’s no longer in business I guess.

They have a few features. They have Dick Tracy, Little Orphan Annie, Gasoline Alley —

And they’re in about five papers.

That’s right. The Tribune Media Service has been losing strips. They’ve been jumping over to other syndicates.

The only strips they have left are story strips, which are way down in the popularity polls of the comics page. So everything they’re doing is just not helping.

But newspaper comics are powerfully appealing. Tell about the time you visited a military hospital and there was a wounded Vietnam soldier who hadn’t talked to anybody.

I used to do a lot of that — go into hospitals. You’d go in and do a drawing and they get real excited about it. I went in this one hospital — I think it was around Fort Dix in North Carolina. And there was this guy lying in back of the ward with his back towards the door. He never talked to anybody, they told me. The nurse who took me around took me to his bedside and said, “Mr. Walker would like to draw something for you …” But he didn’t respond at all. The nurse said, “He draws Beetle Bailey …” Still no response. And I said, “Here, I’m gonna draw Beetle Bailey for you.” And I started drawing. He started peeking around, looking at it. Next thing you know his head came full around, and he opened up, smiling. It was just a transformation. The nurse said, “That’s the first response we’ve had from him!”

He said something, didn’t he?

Yeah. He said, “Oh, thank you.” I gave him the drawing.

Thanks, Mort.