To change the subject a little — do you think of Beetle Bailey as an Army strip, or is it something else?

I’ve always thought that what I would like it to be is representative of somebody who’s caught in the system that they have to resist in order to exist. [Laughter.] Whether he’s a policeman or a fireman or anybody who’s in a large corporation where they’re caught and treated like scum and forced to submit to stupid rules and activities that they really don’t like to do. But they have to do them. And I think there’s thousands, millions, of people that are stuck in a situation like that and I think they enjoy seeing Beetle doing what he does.

As he went from Beetle in college to Beetle in the Army, he’s not the Sad Sack and he’s not Private Breger, both of whom were kind of abused. Beetle is a little craftier than that: He’s not a loser like those guys, but he can never win either, that’s part of being at the bottom of the heap.

He does win in his own strange ways.

He has little victories.

The strange thing about it that I’ve developed is that Sarge will beat the hell out of him, and then they’ll go out and have a beer together. You know, they’re friends, even though they fight all the time. It’s just like when I was a kid, we used to wrestle and fight each other. I remember with my buddies, we’d pin ’em down on the ground and get a neck hold on ’em — they’d scream to get up. And I see my grandchildren — that’s their recreation, these boys. You don’t see girls fighting like that. These two little boys [grandsons] of mine that are coming next week, they just roll upon each other and grab each other and punch each other and laugh! So, in a way, that’s really what Beetle and the Sergeant were doing. I know that Sarge likes Beetle, even though he beats up on him, and Beetle tolerates Sarge, you know?

[Laughs.] Were you tempted during the Vietnam War to do anything about that? It’s like Beetle Bailey’s Camp Swampy exists in a universe where no Army ever goes to war.

I hardly even ever mentioned it. My first reaction to it, I was tempted to send him to Vietnam since that’s what he’s trained for. But then I thought, no, because if you look at the history of comics, you see that the minute a war was over, the soldier characters were finished. And also, I thought he’s got the common experience of basic training that everybody does, that everybody can relate to. So if I put him on a certain military unit or office or a supply corps or something like that, it’s not going to relate to the readership. So I decided, based on the history, to keep him, sort of, where he is.

Besides, there’s nothing funny about war.

Yeah. I get angry letters every now and then from people. I got two angry letters last week when I ignored Pearl Harbor Day, and I had another gag about Miss Buxley finding the general’s calendar with a big circle around the date, and they didn’t know what it was for. So, they said, “Maybe it’s his anniversary or maybe it’s when he became a general or something like that.” And so they arranged a big party ready for him when he came in: “Happy Whatever, General!”

And he said, “You’re throwing me a party for my income tax review?” It was Pearl Harbor Day, but I work several months in advance. In fact, I’m working on stuff just now that won’t appear for probably 15 weeks. So I just missed it.

But there was a sequence in Beetle during the Vietnam War when people were picketing the camp.

Oh yeah, I’d do something like that every now and then, because that was a pretty common thing. The liberals were out there, doing demonstrations and everything. You sort of have to touch on them sometimes.

You did a strip sometime in the last three or four months in which there was some comment made about, “Old men ought to go in to battle,” or something on that order. Am I remembering this right?

Yeah.

Now, there was an element of humor there, but that was a comment about war itself. If old men had to go into battle — the leaders and movers and shakers of the nation — maybe they wouldn’t be so eager to declare wars.

I get a comment, a serious comment, in there every now and then. I try to veil it with humor.

In another one, Zero, I think, is talking about war and peace and Sarge or someone else says that in about 3,000 years, there have only been 30 years of peace. So, we should train for peace instead of war because we’re obviously not much good at it. [Laughs.]

Well, every now and then, I did put one of my pet peeves in there. Instead of attacking people, let’s sit down and talk a little bit, see if we can work out a compromise. You’re never gonna work a compromise if you go out and kill everybody’s poor families.

Beetle says, “There’s wars going on all over the world.”

And Zero says, “I wonder why wars are so popular?” That stops you. People say, “Oooh, hmm, wait …” And Sarge talking about how the weather guys on TV are allowed to make mistakes, just like the president. [Laughs.]

You know where that came from? I had an electrician working here, and he was trying to repair mistakes, some other electrician’s mistakes. I said to him, “I guess we’re allowed some mistakes.”

And he said, “Yeah, like the president!”

I said, “Uh-oh.” And I went away and wrote it down, and I sent him a copy of it. So sometimes, you know, these lines come to you from the blue. I had to hurry that in so it applied to Bush. [Laughter.] I didn’t want to say that about Obama.

Not yet anyway. Could you comment a little bit on some of the characters in Beetle?

Almost all my characters are based on real people. Killer: I had a roommate one time in the Army, all he ever thought about was girls and getting laid. I’d try to get him to go out to dinner with me or go to the movies; he’d say, “Nah, nah — I’m going to town.”

I’d say, “What do you do in town?”

He’d say, “I just walk down the street and every girl I pass, I say, ‘You wanna fuck? Wanna fuck?’” [Laugher.]

I said, “Don’t you ever get slapped?”

He said, “Every now and then, but one out of 10, I score!” So, that’s Killer.

And Plato is based on Dik Browne. Zero’s not based on anybody I knew, but just a lot of the real nice cornfed people in the Army that I met who were real nice guys but just didn’t know what was going on. Miss Buxley is Marilyn Monroe.

You put her in the strip because Sylvan Byck said you’d better have a pretty girl in here somehow?

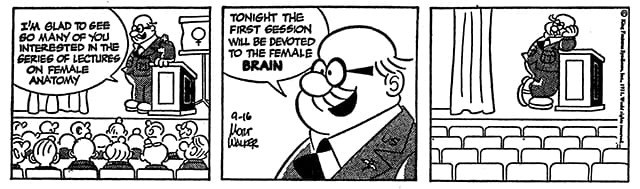

He said, “You gotta have a pretty girl in here. People like to look at pretty girls.” My early pretty girls were almost realistic at first; they weren’t cartoony. And little by little, I made cartoons of ’em. But I had a lot of trouble with Miss Buxley with the feminists. Oh, I couldn’t beat them. I remember I was on a television show, Phil Donahue’s. And when I went into his office before the show and we were talking, this girl comes in and says hi, and she sits down and I said, “What do you do?”

And she said, “I’m gonna be on the program with you.”

I said, “Oh?” I thought I was getting interviewed. And when I got on, I found out that the whole program was about me being a sexist. [Laughs.]

Did Donahue warn you about this?

No. I thought it was an interview with me about the strip. Instead, it was about all the complaints that the women’d had about the General’s attitude towards Miss Buxley. And I said, “I grew up with Esquire where the boss is always chasing the secretary around his desk or giving dictation while she sat in his lap and stuff like that.” I said, “I just thought that was a natural source of humor.”

“We don’t like it. The big breasts you put on her. How would you like if we drew you guys with a big bulge in your pants?”

I was shocked at that, I said, “Nobody is interested in that.”

Yeah, right! [Laughs.] This woman that was on with Donahue, she came loaded to take you on.

Well, she knew what was going on, but I didn’t.

Talk about being taken by surprise!

And there was a woman editor up in Boston who objected to the sexism in the strip and dropped the strip. And she later went on to some place out in Colorado, became editor out there and she dropped the strip, then she went to Florida and she dropped the strip. So, I finally figured out I had to do something about it. But I didn’t know what to do. My son-in-law said, “Send the General to sensitivity training.”

I said, “Do they have that?” and he said, “Oh yeah.” So, I did that and it cleared the whole thing — no one would object to it any more. I gotta be careful, though. Every now and then when I do a strip, I do an idea sketch and Greg and Brian say, “You can’t use that one!” I still have that in the back of my mind somewhere

that it’s OK to tease a woman when you say hello or to whistle at her.

So much of the comedy there was the general being an ass. He was the object of ridicule, not Miss Buxley.

Yeah, but he was using his authority to make sexual comments. That’s what they were against, but I don’t blame ’em. I don’t think I’d want to be in an environment where someone’s always trying to get me in bed. [Laughter.]

Really? [Laughs.]

Depends on who it is! [Laughter.]

My sense is that when Killer came into the strip, he was a very popular character initially, because he was different from some of the others; he was so focused on this one thing. Maybe it was the wiggling of the peaks of his cap.

Everybody knows a guy who has sex on his mind all the time. So I caught the character of him. Of all my characters, Zero is a very popular character in Scandinavia and I asked Alf Thorsjö [who edits and translates the Scandinavian Beetle material] why. He said, “All the women want to mother him. He’s just a sweet, innocent kid. And all the women want to take him in their arms and teach him.”

You had another character for a while that I liked: Ozone. He was sort of another Zero, except he was a heavy-weight.

I guess I just felt like I had enough dumb characters. [Laughs.] I didn’t need any more.

Say something about Sarge.

I had a sergeant when I was at Washington University. His name was Octavian Savou. And he was a great, big heavy guy, just always ordering me around. And we were scared to death of him. He was very severe. We’d run and hide sometimes. And he made our life miserable, just going through the combat course all the time. Then one day we came back from a grueling day, and there on our bunks was a mimeographed poem, “To My Boys.” He had written it, mimeographed it, and put it on everybody’s pillow. We all looked at each other. “It sounds like he’s got a heart! I didn’t know he had a heart! And he thinks of us as his children, his boys!” That was a revelation. So that’s where I got Sarge. I find it’s good to base your characters on real people. Then they became real to the readers.

I was just astonished recently, last year, when I had all the guys come to mail call. They were handing out the mail to everybody, and Sarge didn’t get any. The guys said to Sarge, “Sarge, how come you never get any mail?”

Sarge says, “Mail? Who wants mail. I don’t care about mail. What’s mail? You guys get all the mail you want. I don’t care about mail.”

He’s back in the barracks, and sitting on his bed, with a little tear coming out of his eye. It was a kind of sad. And the whole country responded to that. Schoolteachers made it a little exercise in class to write a letter to Sarge. They sent me these letters. I got letters from kids all over the country. A typical letter was, “Sarge, don’t cry. Here’s a letter. I hope it makes you happy.”[Harvey laughs.] It was really touching. But it was almost as though Sarge was real and they felt sorry for him. I thought that was a triumph for me, to realize that I had characters people cared about too.

Aren’t they real to you?

Oh yeah. I have to remind myself every now and then that they aren’t. [Laughter.]

You said in an interview years ago that one of the ways of coming up with ideas is to take two personalities, whoever they are, put them together, and just have them talking to each other and pretty soon a gag comes out of it.

It helps. It’s an easy way to think of ideas, and on top of that, it can make a less interesting idea into a more appealing idea, to have real characters perform. Like in the movies, you just can’t have anybody perform in a certain movie, you have to get someone who exudes certain feelings and some charm or whatever, that comes out of the screen into your heart.

Some of the early characters didn’t survive. There were three or four of them …

Lots of them, lots of them.

… introduced almost at once. Bammy, who spoke with a Southern accent. I wondered why you didn’t keep him. I mean, there is always a guy with a Southern accent in any unit in the Army. [Laughs.]

He just didn’t seem to have a role, a definite role. I had a guy named Pop who was married and lived off the base, and it was almost confusing. I’ve had dozens of characters I’ve dropped. Bitter Bill I had starting out. He was a guy who was always sour about everything. But it was kind of duplicating the role of Rocky, who was the real rebel, the antiestablishment guy. I needed one guy like that.

I think that the first strip with Lieutenant Flap in it was one of the great comic strips in American history. [Walker laughs.] There’s a pull and a push and a push and a pull, and it just rounds itself out perfectly, it seems. Sarge’s double-edged “help” was absolutely perfect.

That was funny. Not so long ago, I had an exhibit at the State Department, and Colin Powell said he wanted to meet me, so Cathy and I were introduced to him in his office. He was so friendly and everything. He said, “I read your strip.”

I said, “Really?”

He said, “Oh yeah. I remember when Lt. Flap came in, the first strip. The first thing he said was, ‘How come there are no blacks in this honky outfit?’” He laughed and laughed. [Harvey laughs.] So I was very flattered to know that Colin Powell had read the strip and was interested in it. So we had a good time talking about it.

That was just the perfect way to introduce the character. All the problems of bringing in a black character at that time, in 1970, and that strip just laid them all to waste. [Harvey laughs.]

You know how that happened? I went to a party, and there were some black people there who worked for Ebony Magazine. And they latched onto me and said, “You’re drawing a dishonest Army.”

I said, “Why?”

They said, “You don’t have any blacks in it. You go to the Army, they got a load of blacks in it. You got to put a black in the strip.”

So, I talked it over with the syndicate. I said, “I’ve got to put a black in it.”

They said, “Boy, you’re asking for trouble.”

I said, “Well, I’ve got to do it.”

They took me to the 21 Club, fed me martinis, trying to talk me out of it. Couldn’t do it. Finally, they said, “Oh, the hell with it, go ahead and do it.”

Then, when I tried to create the character, I thought, “Well, if I make a guy like Beetle, who sleeps all the time, the blacks are going to object. If he’s chasing women like Killer —. It seems like anything I’m going to do with him, they’re going to object to it.”

So, I didn’t know what to do. I went to sleep that night, after working with him all day long, and all of a sudden, this vision of this guy with an afro, an officer, who was frank and outspoken in character, popped into my mind. I woke up, I thought of the first week’s strips, and I gave each one of them a name so I could remember them in the morning after I woke up. And when I woke up the next morning, I remembered every strip, and I sat down and I drew the whole week, all at once. That’s the way it happened. He was a strong character, black, and he’s an officer.

Boy, they bought right into it. I lost about 10-15 papers in the beginning when I did it, and got them all back later. But then I picked up all the papers in the Caribbean, different places [Laughs].

Hank Ketcham created a black kid for Dennis and it was a disaster.

I know.

But Hank made the mistake of making the kid a blackface character. I mean, he was right out of minstrel-show stuff. And you didn’t do that with …

Mine’s silver gray. [Laughs.] But you can tell he’s black, because of the formation of the moustache.

Yeah. That was a brilliant job, Mort. [Laughs.]

Thanks. I really work at the strip. I give it a lot of thought. One of the things that I always wanted, because I was so poor when I grew up — I didn’t have a dime in my pocket — so I wanted to make money. I thought, “The way to do it is to really create a good strip that a lot people are going to like. Make it have broad appeal, and make it as funny as I can.” And that’s what I try to do with all the gags that I showed you this morning, 80,000 gags that I haven’t used yet, all can be used after I die [Laughter].

I just wanted to be successful. A lot of people object to me not getting into politics like Garry Trudeau. I think, the minute I say, “I like Bush,” I’m going lose half my readers. If I say, “I dislike Bush,” I lose half my readers. So I don’t want to do that. I stay away from controversy, politics, pretty much.

How did the comic-book Beetle Bailey get going?

It was very early in my career and a syndicate guy calls me and says, “Well, we signed a comic-book contract.”

I said, “Oh, great, great.” So I just went back and went to work and a month or so later I was talking to someone and said, “When are they going to tell me to do the comic book?”

And he said, “Oh, we got somebody doing it.” Which is typical at King, they don’t let me do the artwork.

“Who’s doing it?” So they told me he’s part of the bullpen. So I went to him and asked him if he was working on it, and he said, “Oh, I’m just getting started.”

I says, “I think I want to do it myself.”

So he says, “OK.” So I went back and told Sylvan, I’d rather do it myself. I did the first couple of comic books by myself, wrote them and drew them. But it was a lot of work. They were coming out monthly, or every two months. [Every other month in the ongoing series, beginning with April 1956; but Beetle’s first appearance in comic books was in Dell’s Four Color Comics, Series 2, with #469 in May 1953.] That was a lot of work. I asked Tony Di Preta if he’d like to give it a try. So he did for a while. I wrote; he drew. When he first came by to talk about it, he said, “Ah. Blah blah blah, I draw realistic figures.”

I said, “That takes time. You’re stuck with this.”

Afterwards, he came back and he said, “You know, your stuff is tough to do. Every line has to be exact, you can’t sketch in anything. That’s very, very exact, just the way you did it, or it doesn’t look right. I’m having a hard time.”

Did he finish one, or did he —

He finished one. So then Jack Mendelsohn wrote for me for a while. He wrote, and I think it was Frank Roberge who drew it for a while before he started working for me as an assistant. [Roberge did Mrs. Fitz’s Flats, a Walker conception that started in 1957.] And then I can’t remember everybody who did it. Bob Gustavson finally took it over, did a wonderful job.

And he did it for most of the run?

He wrote it and drew it. Then he also did all the work for the Swedish and Scandinavian comic books.

How did that Sweden thing get going? You’re at least the third strip cartoonist I’ve talked to who has a big following in Sweden.

Well, I was lucky in a way. We had some dealings with Alf Thorsjö — he was the editor of my comic books over there. And, the big comic book over there is Donald Duck and then there was The Phantom. Down the line somewhere was Beetle Bailey.

Now, this comic book was the American comic book that was translated into Swedish?

No. They used my printed work from King Features, the daily strips and Sundays. Anyway, Alf wrote me and said, “You know, they’ve got college students in English translating your work.” And he said, “They don’t seem to have a sense of humor, or of how to write these things. You need a cartoonist or somebody like that to translate your work.”

And so I went to King Features and I told them. And they said, “Well, have you got any suggestions?”

And I said, “Alf Thorsjö is a cartoonist. He seems to speak English pretty well.” So, once he started translating everything, our popularity just grew by leaps and bounds. And then he started editing the comic book. He began putting my picture in it, my picture on the cover, and writing little stories about me inside, special things like a contest, and the comic book just took off. It really took off.

This is a comic book that is essentially reprinting the daily comic strip?

Yes. Then we started doing special work for them. As I said, Bob Gustavson did all that, for a long time. And, I think the care he gave it, the enthusiasm he gave it in making me a character. I mean, I was famous over there. I went over to the book fair one time, and Cathy and I walked down and we saw a big long line in the street, waiting to get in. I said, “Boy, they must have just opened up the doors, there’s a lot of people waiting to get in.” I got in, the line went all the way around through the whole floor, to my booth. I realized that that was my line. [Harvey laughs.] I sat there, signed autographs.

The manager of the book fair came over and he said, “I’m going to have to move you. Everybody’s complaining that your line is blocking their booths, and they paid a lot of money for these booths and you’re here. We’re going to move you upstairs, in the back hall there, it’s all empty.”

We had a very elaborate booth where we were, with a television set, animation, all kinds of stuff. We hated to move, but we went up there and they set up a desk for me. I stood there for three hours signing autographs: never saw the end of the line. They came to me, they said, “You’ve got an interview you’ve got to go to.”

So I had to say, “I’m sorry, everybody.”

And they said, “Oh, we’ve been waiting for hours.”

I said, “I’m sorry, I’ve got to go.”

They gave me a plaque for having the longest queue line in the history of the book fair. I’ve got it in there: a plaque. They said they’ve never had a line that long. Then in subsequent years, they got a little plan for cutting down the line. When they saw how long the line was getting, they’d go and put one of their people at the end of that line, and anybody else that came up they said, “Sorry, this is the end of the line, he’s not signing after this.”

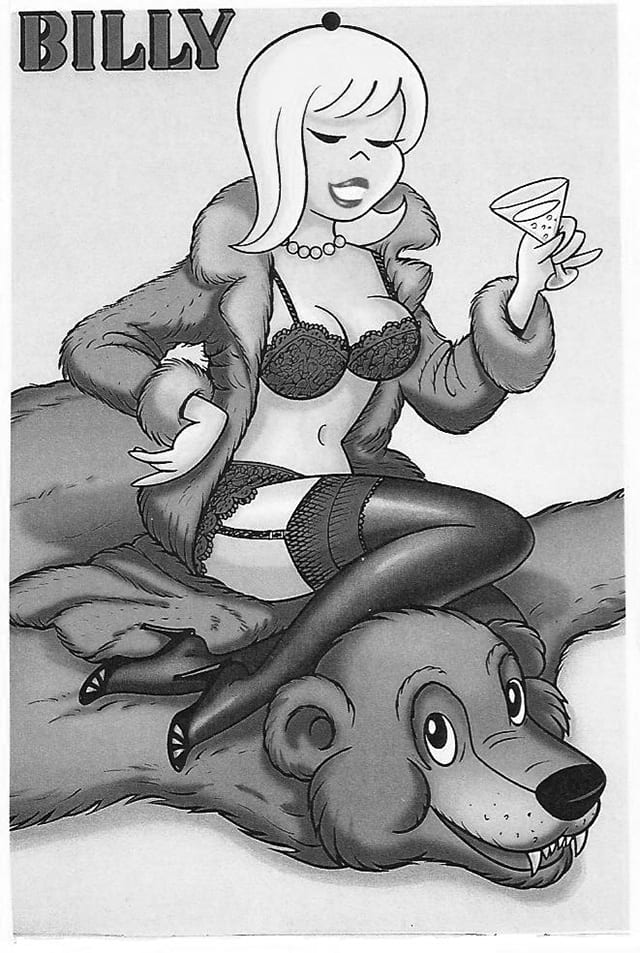

So we didn’t disappoint people. But it’s still just amazing the amount of attention Beetle gets over there. He’s got books, and the “dirty” books and everything: toys, products.

Tell me about the “dirty” books. [Laughter.] These are gags that you and Jerry and the rest come up with that you know you can’t get in this country.

Right. So they use the regular pencil idea sketches of mine in English, and they make a book out of it.

They’re not finished art. They’re pencils.

Yeah. They’re not all mine, either. [Harvey chuckles.] They’re Jerry’s and Brian’s and Greg’s. So anyway, everything put together has just become a very, very popular feature over there.

Somewhere I read that you did a certain number of graphic novels for the Swedish.

Yes. There’s a guy, a cartoonist, I’m trying to remember his name, who’s into the graphic novels over there, which are very, very popular. And he came to me and he asked me to do some graphic novels for them. So I said, sure. So I did all those myself. It’s funny. I took the whole job up to my house in Vermont, Quechee, Vt. I’ve got a nice house up there, a couple of bedrooms, a couple of baths. I decided the only way I was ever going to get some work done, was to go up there and get away from here, and get away from family. I decided to go up for a month, and I took Curt Swan with me. He worked on Superman pages in one room while I worked on the graphic novel in another room. We’d get up at 5:30 every morning, and go to work. At about 2 p.m., we’d quit, have a drink, go play golf. We’d come back about 6 or 7, have a couple more drinks, have dinner, and go to bed, wake up. We did the same thing every day. I used to do five pages in a day, pencils. I did the inking later. He did all his Superman stuff. We had a great relationship, a lot of fun.

How do graphic novels differ from the comic strips — from a storytelling point of view?

One story runs, say, 35 pages. That’s a lot different from telling a gag. I tried to have a laugh at the end of every page, but that’s pretty difficult sometimes. I developed new characters; in one of them was a new sergeant. Sgt. Snorkel is only a tech sergeant, I believe, but the full sergeant, the master sergeant, was above him. So I brought in this guy above Sarge. And then did stories about all the trouble they had with each other: Sarge became deflated, demoted and the other guy had an ego. And anyway, I thought they were good stories. There was one about Sarge trying to lose weight. I had some sex in them a couple times, a lot of half-naked girls, which you like.

Yes, right. [Laughs.] Didn’t you vary the page layout and the size of the panels and things like that?

I had big panels and little panels, and whatever I wanted to do. The whole page was mine. It was different from the regular Sunday pages, where you have to maintain a certain format for different sizes of the strip. Sometimes newspapers stack it, sometimes they work them in different formats, so you have to keep the same layout. So the graphic-novel pages were just fun to do. I don’t know how many I did, but I think they did four of them here in English.

When was this, ’70s or ’60s?

Seventy-something.

The graphic novel didn’t really take hold in this country until the ’90s, I think. And now, it’s just going gangbusters: You get graphic novels reviewed in respected grown-up magazines and newspapers. So it might be better now. You might do better with those very stories you’ve done before.

I don’t know, because most of the graphic novels I’ve heard of and seen reviewed are usually about somebody’s terrible pain, homosexuality or the Holocaust or something like that. But they’re all dark. Are there any funny ones?

Yeah. [Laughs.] But the humor is different than you find in daily comic strips.

I might try them again, then. The next thing that happened over there was the reprinting of Beetle Bailey, the Complete Beetle Bailey project, and that got started fairly recently, just a little over a year ago, I think. They just continue to turn them out every couple of months. But they do a beautiful job.

I don’t know anybody else doing daily comic strips who does this much collaboration, who has this sense of working with people that you have. How did that begin? Was it just a case of starting with one assistant and branching out?

Jerry Dumas was my first real assistant. I had Fred Rhodes for a while and Frank Roberge for a while. They went on to other things. They never worked the way Jerry did. Jerry and I just always got along fantastically. We’ve been collaborating 52 years. [Harvey laughs.] We’ve never had an argument. We always just worked really well together and I admire his talent, he admires mine. I work well with people. I never criticize too much. I work with enthusiasm, brains. I like to create a good atmosphere. I always worked really well with all my workers, except for my wife. [Harvey laughs.] The first one. That was her fault though.

Several times over the last day or so, people have alluded to what Brian called the Golden Age of Cartooning in Connecticut. It was a great number of major cartoonists that lived in the same community.

It really was. I guess they called it The Infestation [laughter].

Well, was there an active social life in that community? Did you get together frequently?

Always. Once a month we had a group that got together and had dinner at a restaurant, and then we’d take turns going back to certain persons’ houses, and drink and talk and … do some drinking, and do some drinking … [Laughter.] We had just a great time. We were all good friends. There was just so many of us. Then we’d have our cartoonists’ meetings up here, play a golf game. I just had my 51st golf tournament — the Connecticut Cartoonists Invitations — so I’ve been running it for 51 years. The trouble is, they’re all gone now. There’s maybe fewer than 10 cartoonists left in the group. And everybody else who plays in it, they’re just affiliated people that we know, invited in. But it used to be all cartoonists: We had about 50 of them. We’d play golf, then we’d get together to tell jokes and afterwards have dinner, prizes. This year I had at least two prizes for every person. I got all the waiters and cooks, everybody got prizes: I still had stuff left over.

Well, did anybody refer to this conclave of cartoonists as the Connecticut Rat Pack, or anything like that?

I think the Jerry Marcus group must have called themselves the Rat Pack. They were just a little group that was up in the northern part of Connecticut. But the larger group, we’re just called the Connecticut Cartoonists, we’re still called that. Brian runs that. And we get together three or four times a week for years. Except for the golf tournament, it’d be a party that gathered around a dinner or a restaurant setting, that branched out to drinking as long as anybody could stand up. [Laughs.] The drinking is way down from what it used to be. I tell you, it used to be pretty bad. We’d go to New York, and some of these guys would fall down over tables and have to be helped home, get sick. I’m trying to remember some incidents. It just seemed like they shouldn’t have been driving home, and they did.

So, if you were in New York, people wouldn’t drive home from there; they’d stay overnight, wouldn’t they?

Well, some of them did. They’d get lost, didn’t know where they were going. That was completely irresponsible. But usually, when we found out we were going to drink, either one person would not drink as much and he’d drive us home, or we’d take the train. We’d get on this train every now and then; we’d just have a raucous time. But those were the days, I tell you. It’s all disappearing. All of these groups, that we met in all the time. At least once a week, we’d go down to New York for meetings. Then we’d have all those meetings out here. We had a bowling league; we had a golf group; ping-pong tournaments; all kinds of stuff.

And the ping-pong tournaments would eventually degenerate into late-night drinking?

Usually everything did, yeah. [Laughter.] It was an inspiration for drinking. I don’t know how we ever invented that, but —

And yet everybody would go home afterwards and wake up in the morning with a hangover and face that blank piece of paper —

That’s one thing. I never got hangovers. I always thought I was drinking very moderately. But I drank a lot, and I guess it began hurting my stomach. I still have some damage in there. I’ve got to take an antacid pill every morning. So after that I quit. Every now and then, you miss it. When you go to meet somebody and they’re not there yet, what do you do? I used to sit at the bar and have a drink while I was waiting for them. Or going to cocktail parties — what do you do now when you go to cocktail parties? Have a soda. It’s not as much fun. [Harvey laughs.] But in the long run, I wouldn’t trade it for anything, being sober, being able to think straight, keeping my health, that’s the main thing. Here I am going on 86, and I still feel young. I still play golf, get around and sleep well. Feel good.

I think that older people are sometimes very hard to manage. There’s a little bit of dementia that goes along with old age. It’s not too critical, but you do begin to forget things, drop things. I was dropping so much stuff that it got to be irritating. So I went, “You know what I’m going to do? I’m going to start counting whenever I drop something.” And boy, that cut it way down. I can go the whole day now and only drop maybe three or four things. That’s usually not my fault; it’s usually, I brush against something and it falls down, or I kneel down behind the bar and a corkscrew that’s sticking out gets caught in my pocket. [Laughter.] I learned how to deal with a lot of my inabilities. Like, my hands are so stiff that I can’t make a fist any more [shows Harvey]: this is the biggest fist I can make. It’s kind of clumsy. I don’t pick up things easily.

Well, you can handle a pencil.

Hasn’t seemed to bother my drawing at all. At least, nobody’s complained about it. [Laughs.] I draw faster. The other day I did a whole week, dailies and Sunday in about two hours, two-and-a-half hours.

We already talked about the origins of Hi and Lois. Can we go through the rest of them — like Mrs. Fitz’s Flats — and a little bit about how they came into being?

I had a friend named Herb Green who was a gag cartoonist. He was a college buddy of mine. When he came to New York, he became my best friend — his designation. And every night at 5 o’clock, he and his wife would drive up the driveway and come in, and he’d spend the evening. It got to be irritating. We just had other things to do. But he used to call himself my best friend.

So I looked at his drawings one day, and I said, “You know: You’ve got some funny-looking characters.” I said, “I wonder if I could get them all into one strip.” I thought about it: “How about a landlady that owns a building, and she has all these tenants, and they interact with each other.” So, I created the thing based on his characters, and I called it Mrs. Fitz’s Flats. I thought it would probably be very popular, and as I was getting prepared to show it to Herb Green — I hadn’t even showed it to him yet, hadn’t even told him anything about it.

Frank Roberge, who was my assistant at the time, said, “Look, you’re going to give that to Herb Green?”

I said, “Yeah.”

He said, “Give it to me, or I quit.” [Harvey laughs.]

So I said, “OK.” He did it. He went to work on that. It was moderately successful: I think we had, maybe, two or three hundred papers. He ended up doing all the gags, all the drawing and everything.

Mrs. Fitz’s Flats was a partnership with you and Frank for a period of time, and then he went off by himself, is that right, or did he go off by himself right away?

Right away. I just couldn’t write another strip. I never intended to write it. I think I wrote maybe the first month or two, or something, just to get him started.

It lasted a long time. Fifteen years [1957-72].

Did it? Well, he was still drawing it one day when his wife looked in and he had suffered a heart attack right on the drawing board.

Just like that. And that was the end of the strip, too. What about Herb Green? What did he have to say about all this?

Well, Herb Green got to be a real problem. Every time we threw a party and he was there, he’d get in a fight with someone. I don’t how it would get started. But he’d say, “Come out to the driveway, we’ll settle this.” He was always taking them out in the driveway to fight.

One of the worst times was when Jerry Dumas was getting married: We had a bachelor party in the basement of my old house where I had a pool table, a ping-pong table. We were having a great time. Somebody came to me and says, “That guy over there. Either he leaves, or I leave. I can’t put up with it.”

So I went to Herb and I said, “What’s going on?”

And he goes, “OK, Skeezix, all right, Skeezix, we’ll do it your way Skeezix.”[Harvey laughs.] And he’s just irritating. And he called me the next day to thank me for the party, and he said, “It was great.”

But I said, “Herb, you weren’t so great.”

And he said, “What was wrong with me?”

And I said, “Well, you were drunk and your childish behavior causes everybody to fight and people were getting irritated. They were leaving the party.”

He goes “Oh, OK.”

He calls back about two hours later and says, “OK, everything’s all right. I called everybody at the party and apologized, OK?”[Walker laughs.]

I said, “Herb, I can’t put up with it any more. You get into a fight every time you come to my house for a party. I’m afraid I’m just going to cut the friendship off.”

So I did. He went on, got a divorce, he went to teach school somewhere. Nobody ever sees him any more.

Did he recognize that the characters in Mrs. Fitz’s Flats were characters he had drawn, or he had invented?

He never said anything about it. But I was glad I didn’t get into a partnership with him.

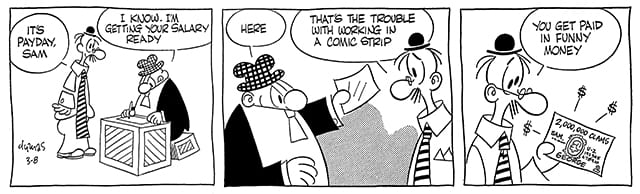

Then came Sam’s Strip.

Now, that was just a drawing that we started messing around with — the artist, Jerry [Dumas], and I. When I went down to sell it to King Features, and I told them that what I was going to do was to make fun of other comics cartoonists, they said, “Don’t we have to get permission for that? That’s not going to work. We can’t do this strip.”

I said, “No, you don’t. You don’t have to get permission. This is satire.” I said, “We’re just going to have fun. We’re not going to make anybody mad.”

They argued with me, and finally they just said, “Well, OK, if you want to do it, go ahead.” [Harvey laughs.] But I don’t think they ever had any enthusiasm for it. It’s interesting how often I’ve been met with this criticism, and then they just go do their job, which is to sell it. Sam’s Strip was extremely popular among the cartoonists. They really liked it. But it appeared in the New York paper, and they all saw it.

It never really had wide circulation, but we enjoyed it so much, and we had such a good time doing it, that we wanted to go on doing it. But then, when that paper pulled it, when the Journal-American pulled it, and it didn’t appear in New York any more, we noticed that it just wasn’t fun. We didn’t get the comments or the feedback, so we just decided to end it all. I think it was five, 10 years later that the editor from there at NEA called up, and they wanted to do it. That’s when I went to talk to the president at King. He said, “No, we don’t want you to go to another syndicate. But if you want to revive that strip, do it in a different way, don’t do the same satire.”So that’s when we created Sam and Silo. [It started April 18, 1977.]

The Laurel and Hardy of the comics [laughs].

That’s exactly what we talked about. [Harvey laughs.] And it’s still going. For 26 years. I enjoy Jerry’s drawings so much. He fools around and he does more than he needs to do, but it makes it beautiful. Every now and then, he gets inspired to do a nice city scene with trees and rocks and stuff like that. He gets a big kick out of it. The thing is, it’s not very widely syndicated, but boy, in Greenwich where he lives — they run it there. He’s the big chief in Greenwich. They think he’s the greatest artist in the world. Then they gave him a column to write, and he’s a cartoonist and a columnist for that paper. The column comes out once a week. It’s very popular.

The next one was The Evermores, which started in 1982.

That was a strip I had that I still think had a good premise. I hate to go on blaming King Features all the time, but they just didn’t seem to be very interested in it. The idea was that over the years, since the beginning of time, married couples have had the same problems, just a different setting. I wanted to call it The Same Couple, so people would understand what I was doing, I’d have them in Alaska where they were Eskimos, but they were the same people, the same characters. I’d have them in Roman times. I’d have them in various settings. I thought that would be interesting, for people to realize husbands were always this or that, or women were always like that, and having it in a different setting would give it some interest.

Well, they didn’t like the title The Same Couple. So, I think Bill Yates came up with the idea The Evermores, which he thought people would catch on to. Nobody caught on to it. Nobody got the idea that this was the same couple. It went for a couple years. We just finally gave up on it. If something doesn’t sell the first year, then they really lose interest.

I think you’ve said this — Milton Caniff used to say it — that you have to promote your own strip, because the syndicate won’t do it, or doesn’t do it. It’s not that they won’t, it’s just that they have other things to do.

Yeah, you’re right. They used to launch two strips a year, at least, and they give you your six months, and if there wasn’t an awful lot of interest in it, they’d stop. They were going to cancel Beetle after just six months because it only had 25 papers. It just wouldn’t sell. I put Beetle in the Army, bingo. It just took off.

The next strip you did was Betty Boop and Felix.

I was up in Vermont in my home up there, and I was reading some books, and I happened to have this book about animation, and I came across Betty Boop and I said, “Boy, that’s a great character, just really captures everybody’s attention, everybody likes her, she’s a bouncy, sexy little girl.” [Harvey laughs.] I turned the page and there was Felix. I said, “And look at that. What a great character that is. That is a beautiful cartoon creation.” And I thought, “And neither one of them are in comic strips any more. I wonder if I put both of them together, and created a brand-new comic strip —?”

And that was one of the problems, I guess, the characters were owned by different people. And there was this confusion: “What’s Felix doing with Betty Boop? Why not just a strip about Felix,” or vice versa.

But anyway, I came back with the idea and gave it to Bill Yates and he said, “Yeah, that’s a great idea. There would be a lot of interest.”

I said, “Then my sons will write it and draw it.”

Neal was drawing it, and Greg and Brian were to write. So anyway, we drew the samples up, and we had a meeting right here around the fireplace with all these executives. There was some reluctance on some people’s part. This woman from California who was instrumental in making Peanuts popular, she objected to it because I think she was selling Betty Boop products, and some of the guys that worked on Felix and the people who owned it didn’t want them to be confused with Betty Boop. So there was some opposition. Then, among the King Features people, as they got up to walk out, one gal and this guy, Alan Priaulx — who would later on be termed as a snake at King Features, and they fired him — on the way out, I could see him going like this [makes a gesture, Harvey laughs]. He never expressed that thing at the fireplace, but on the way out, I think on the way home, he probably gave it his worst.

Then, when they went to sell it, the East Coast salesman either died or quit or something like that. They gave the job to a young girl who was in the office, and she was very nervous about going out. I don’t think she ever sold anything. Anyway, we didn’t have one paper on the East Coast. On the West Coast, the guy out there liked it: We sold it all over there, 50 papers almost immediately, and not one paper here, except Greg sold it here to the Greenwich Times. That was the only paper on the East Coast. I went to King Features and I said: “Now this is really strange. The West Coast, it’s very popular, but we haven’t sold it at all for the East Coast.”

They said, “Oh, the East Coast is a lot more sophisticated than those guys out there.” [Harvey laughs]. That was the argument they gave me. I just didn’t seem to get the syndicate behind me on that strip. It was confusion about licensing rights and whether or not I got any of them, or whatever.

The last strip you started was Gamin & Patches. It only ran a year or so [April 27, 1987-1988].

I was down in Florida, and I guess we were at Disney World. I was waiting. When the kids went on rides, I would not have anything to do, so I was sitting there, and all of a sudden I got to thinking about popular characters of the past. Like in the movie where little Jackie Cooper was the star, The Kid, and how popular that was, the little kid, you know, on the street. I said, “You know, a spunky little kid on the street. That might make a good comic strip.” So I started to work on it. I did a whole bunch of strips, and I had so many strips with King Features, I decided I would try United Feature instead. And they bought it.

But it just never seemed to take off. People said they don’t like reading about a little boy on the street, living on the street by himself. It was frightening to them. I was thinking, “I wonder why they got away with it in the past with The Kid with Jackie Cooper?”

Or Little Orphan Annie.

Yeah. But I guess it was more of the times, maybe there were more kids on the street back then and they were used to seeing them, and seeing one of them trying to make it on his own or something like that was inspiring. I guess it was crippled right from the beginning, but I didn’t realize it wasn’t going to go over. Bill [Janocha] loved it. [Laughs.]

He drew it, didn’t he? Or inked it or something?

[Calls out]: Bill? Did you used to draw Gamin & Patches?

BILL JANOCHA: You decided to give the strip up for like the last six months. I wouldn’t say I ghosted it, but I was involved with several weeks of it towards the end. I finished the full strips, and even got more involved with the gags. We were, from the beginning, working together very much on gags, for sheer back and forth, but later on, we knew that there was an end strategy, and it was an opportunity for me to finish the strip out. We brought in Mrs. Fitz, and even went and reused some Mrs. Fitz gags, too.

WALKER: [Laughs.] It’s funny: I forget what I did.

JANOCHA: It’s hard to recall back 21 years, but as far as the drawing goes, there were a number of weeks where — I mean, I always was involved in it in some extent — but where you would just say basically, “Here it is.” And then there certainly were those backgrounds that were going throughout the strip, the photographic backgrounds that were employed.

WALKER: Oh yeah, that was another device that I thought would be interesting, to take real photographs and use them in the background.

JANOCHA: He would give me free rein to just go ahead, and there was a number of books he had on New York City and other cities, and I just tried to make it not overpower the strip, but give it almost an animation, three-dimensional feel to it.

Who are your favorite humorists? You do a lot of reading, so you must read some humorists work.

WALKER: Back then, Mark Twain was always a favorite of mine, and everybody else’s. More recently, Dave Barry.

Art Buchwald? Did you read much of him?

Yeah, he was good, but I think he was almost too political.

You decided fairly early on that you didn’t want to get into the political humor. In fact, in Checker’s first volume of the Complete Beetle Bailey, there are a couple of strips that were never printed that were the beginning of a continuity; you were going to tell a story for two or three days or maybe a week. But you gave up on that idea too.

Well, you learn. I think I was trying to usher in the gag-a-day strip. At that time, the story strips dominated the comic pages.

How does the writing of the strip get done?

Well, once a month, we all get together — me and Jerry and Greg and Brian — and everybody brings in their quota of gags, which is usually about 30 apiece. So we have maybe 120 or so gags. They’re all sketched up, rough drawings of the strips. And we pass them around, silently — no talking — and we grade them on the back: If we like one, it gets #1; if we’re doubtful about it, it’s #2. And if it’s dirty, it gets a #50 or something like that. [Harvey laughs.] You get four guys together — four he-men guys, like we got, and you’re bound to get some racy gags that you can’t print.

And these, some of them, are eventually published in Sweden in little booklets. They just print the pencil roughs.

Yes. [Laughs.] My editor over there, he comes over here about twice a year, and one time, he saw these roughs and wanted to use them over there. And so we said OK.

OK, so you pass these gags around and you rate them, and then they go into storage.

Well, first of all, after we’ve rated them all, then we get together, and we go over each strip, and we talk about them. Almost always we can improve on the gags, fiddle with the wording or the drawing or something — even the #1-rated ideas. And we can often “save” a #2 gag by re-working it in some way.

When you were doing more strips, the crowd of gag writers was larger, and you were looking at gags for maybe four more strips. Now, does this 120 gags we’re talking about, does that include Hi and Lois gags as well?

No. When Dik Browne died, his sons took over, and Brian was writing gags then too, and Greg. And they don’t want me to do anything with it, any more. They have their own gag conference and their own thoughts. It was time for them to take over, ’cause they had kids growing up and could come up with better gags, like Dik and I did when they were young.

So, the 120 gags that the four of you are working on are all for Beetle.

Yeah. They’re all Beetle gags. Then Hi and Lois has the same thing. It’s just Greg and Brian doing that.

When you went from doing gag cartoons to doing a strip — there’s a difference in the way you present humor. And I’m sure you were conscious of that right away.

There’s a similarity. One of the things is that if you’re doing a gag cartoon, you’re limited to one scene; You don’t work up to the big punch line. I like doing the strip better. But, it’s really just a gag cartoon with a setup.

I think you can always make a strip out of a gag-cartoon idea. But I’m not sure you can make a gag cartoon out of a strip idea —

That’s true, yeah.

Because you don’t have the setup. I remember a couple of the Beetle college strips in which sometimes you were doing four or five panels, and the first two or three were pantomime, they were silent. So the set-up in them was just being stretched out, in effect.

Yeah. I almost had too many panels in the beginning.

The one that I watched you do yesterday was a two-panel strip. Some of them you do nowadays have three panels. You never go beyond.

Very seldom: Our space has been reduced to the point where you can’t have too many panels, because everything gets so small.

Many comic strips now are one-panel cartoons. No setup, just a single picture. It seems to me that the nature of the comic strip has changed a little bit. You take Non Sequitur, and oh, what are these new ones, Tundra and Bound and Gagged. A lot of them are one-panel. They’re gag cartoons, really.

I submitted a strip recently based on all my old gag cartoons. When I was selling gag cartoons back in the 1940s, a lot of them didn’t sell, so I’ve got stacks of gag cartoons. So I thought I could make a strip out of that. So I took it to King Features, and they said, “Well, we don’t think this type of strip will sell.” I try to think of gags every morning before I get out of bed, because I usually wake up a little early, I don’t want to hop right out of bed. I also think it keeps my mind active and young. It’s like working a puzzle every day. It helps me keep my mind active. It’s exercise.

Someplace, I read that you have a regular rotation of appearances: Every Wednesday is a Miss Buxley gag, and every Monday is —

I start Monday with a gag about Beetle and Sarge, then I try to use one of the minor characters on Tuesday. Wednesday is Miss Buxley. Saturday gag is about the general and his wife.

Cont.