Insightful, personal comic strips are rare. Cartoons that make you laugh are even rarer. Michael Dougan does both at the same time.

-Matt Groening, artist of Life in Hell and future creator of The Simpsons, from the back cover of Michael Dougan's 1987 collection East Texas: Tales from Behind the Pine Curtain

Michael Dougan's work is hysterically funny in a dry, self-depreciating way.... He's got a love/hate relationship with Texas, his family, and himself.

-Aline Kominsky-Crumb, editor of Weirdo magazine, from the same back cover

* * *

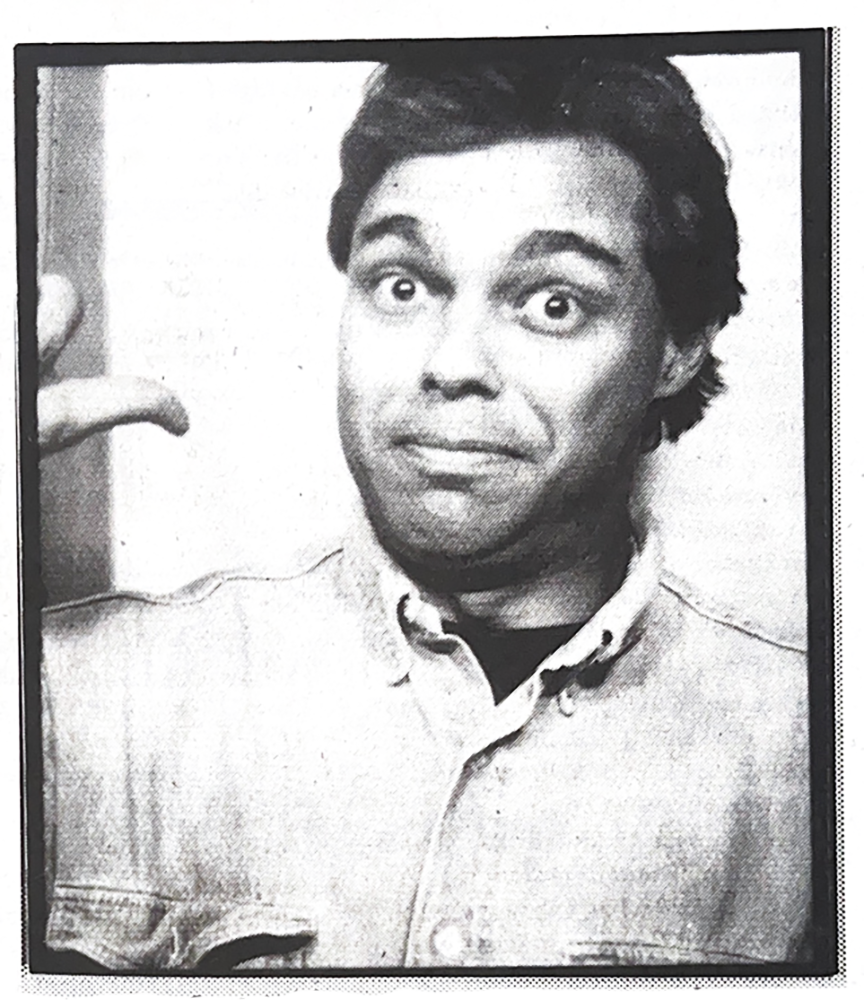

When news of the death of cartoonist Michael Dougan began appearing on social media a few weeks ago, sad tributes popped up from colleagues and fans, alongside images drawn with his distinctive brushwork. There were also an awful lot of comments like, "He was one of my favorites... I always wondered what happened to him..."

I wondered the same thing.

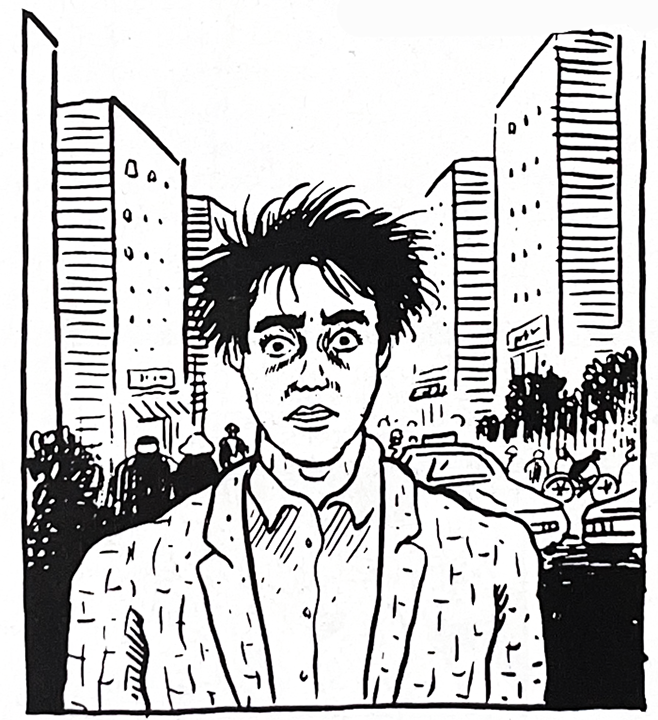

Dougan was like a comet in the 1980s/1990s alternative comics scene, a bright shining star that disappeared far too soon. He was one of the most visible Seattle-based cartoonists in those "grunge" years, a time when that city was placed by many at the confluence of alt music and alt comics. His work was everywhere. And then it wasn't. Mysteriously, and suddenly, he seemed to vanish from sight at what appeared to be the height of his career.

"Why?" many asked.

"His work was everywhere, plastered all over alt-weeklies in eye-popping covers and large illustrations, and as a frequent artist in Dennis Eichhorn's seminal memoir series Real Stuff," the cartoonist Derf posted on his Facebook page. "He published two original books- [one] with Penguin, the then-loftiest of comics-friendly traditional book publishers, back in the dark era when most wanted nothing to do with us. He was one of the first significant names for Drawn & Quarterly. He did lots of cartoon illustrations for mainstream papers and magazines, too, really plum gigs. He was rising fast. I was still scuffling, in a just a handful of weekly papers, and eyed his trajectory with envy and appreciation.

"And then... Dougan vanished. I don't know why. His work simply stopped coming, sometime around 1995. I heard he moved to Japan, to do what, I don't know. He never emerged again with new work. I haven't thought about him in a long time."

The bulk of Dougan's career came prior to the internet's explosion, so there's not an awful lot of information about him online, or many examples of his prolific artistic output. Both of his collections—East Texas: Tales from Behind the Pine Curtain (The Real Comet Press, 1987) and I Can't Tell You Anything (Penguin, 1993)—are long out of print, while most of his uncollected work appeared ephemerally in the alternative press, small-print comic anthologies and as spot illustrations for high-profile magazines. His last published work that I am aware of came at least 20 years ago.

He was a bit of a mystery, missed by those of us knew of his work, and an unknown to the many more who had never had the opportunity to see it. As the late comics historian Tom Spurgeon tweeted in 2019, Dougan "was the guy [who,] when [Art Spiegelman] pointed from the front of the alt-comics army to take the lush comics-possible terrain in front of him[, he] ran over the first hill and we never saw him again."

My hope is that a new collection of his work will soon appear; it's unfortunate that, despite some efforts, there wasn't one published while he was still alive.

"Whenever I brought up doing a collection of his work, he was interested but ultimately dismissed it as being too much of an 'epic undertaking' to find the time for," Fantagraphics VP/Associate Publisher Eric Reynolds wrote in a tribute on January 24th. "I regret not pushing him harder."

* * *

Michael Dougan died in Tōno, Japan, on January 13th, 2023 - the result of the brain cancer he had learned of a year earlier, according to his wife, Chizuko Nitta. He was 64.

"He was a talented man in many different dimensions and I am hoping that you can highlight that," his wife wrote me in an email.

I will try.

Michael W. Dougan was born on July 18, 1958, in Houston, TX, to John Lesley Scott and Claire Nichols Dougan. In interviews, Dougan said that he grew up in a household of women—his mother and sisters—in various parts of East Texas, the setting for many of his autobiographical or semi-autobiographical stories.

In his author's bio for East Texas, he wrote: "Michael Dougan was born in 1958 and grew up in the Piney Woods of Longview, Texas. He moved to America in 1977 and has been telling lies about East Texas since 1985."

"In his childhood, according to Michael, he and his mother moved around a lot, but mostly grew up in Longview, TX," Nitta wrote. "He moved to Seattle in his senior year in high school, went back Texas after graduation, but returned to Seattle shortly after."

Nitta mentioned that while she and Dougan married in 1996, they had first met many years earlier.

"In 1978, we met at the rooming house called Wilhelm's house where Greg Burch (Michael's best friend from Texas) lived and that's where I first lived when I moved from Yokohama, Japan to Seattle to start college," she wrote. "We were still teens. I remember talking about comic books and I told him that all Japanese kids' dream is to be a cartoonist. I drew some cartoon characters and Michael was not impressed. LOL."

Dougan decided at a very early age what his desired career path would be.

"I was drawing compulsively from as early as seven or eight," he wrote in Jon B. Cooke’s The Book of Weirdo (Last Gasp, 2019). "By the time I was 11, or 12, I decided I was ready to go professional, and work at the newspaper, so I applied for a job as a cartoonist, at our hometown newspaper, the Longview Daily News. And went in with my 'portfolio' (which, I imagine, was a paper bag with some drawings in it) and, though my effort to get hire obviously didn't succeed, the editor took me and my work seriously… or pretended to. He was respectful, as if I were an adult, when I applied for a job. I was taken around to meet the people in the art and editorial departments. They kept a straight face the whole time I was there."

Like many, Dougan pointed toward his early exposure to MAD magazine—particularly the Mort Drucker era of movie parodies—as an influence that would remain "well into adulthood."

"I had a subscription to MAD magazine in 1970… other than Boys' Life, it was the only regular subscription I had to anything as a kid," he wrote in The Book of Weirdo. "By high school, I was introduced to ZAP and the undergrounds, we consumed it the same way we did albums, attracted to counter-culture stuff our parents disapproved of or found disturbing. And I completely missed, or skipped over Marvel and DC comics, Kurtzman-era MAD, and comic books in general. By the time I discovered comic books, it was exclusively underground comix, and its reaction to, or rebellion against, mainstream super-hero comics. So I joined in rebelling against a fixture of comics publishing history I frankly didn’t understand or appreciate in the first place."

In his early development as a cartoonist, Dougan was drawn to the work of Robert Crumb, particularly the later, often-autobiographical work done for Weirdo in the post-ZAP years.

"Though there were a lot of other comics artists I was impressed by and whose work I admired, at that time, when I was trying to develop, my focus was pretty narrow," he wrote in The Book of Weirdo. "Crumb was the primary resource. His panels are an endless resource for things like how an old-fashioned table lamp cast light on walls, surfaces, or reflections in glass, creases in clothing. And how that translates into pen or brush strokes."

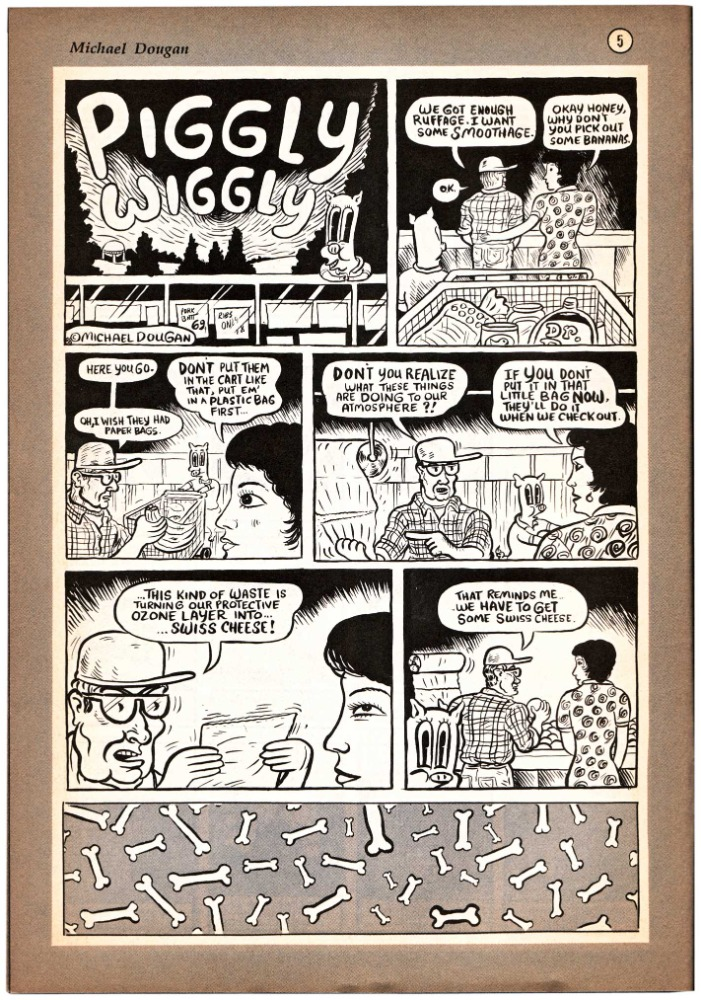

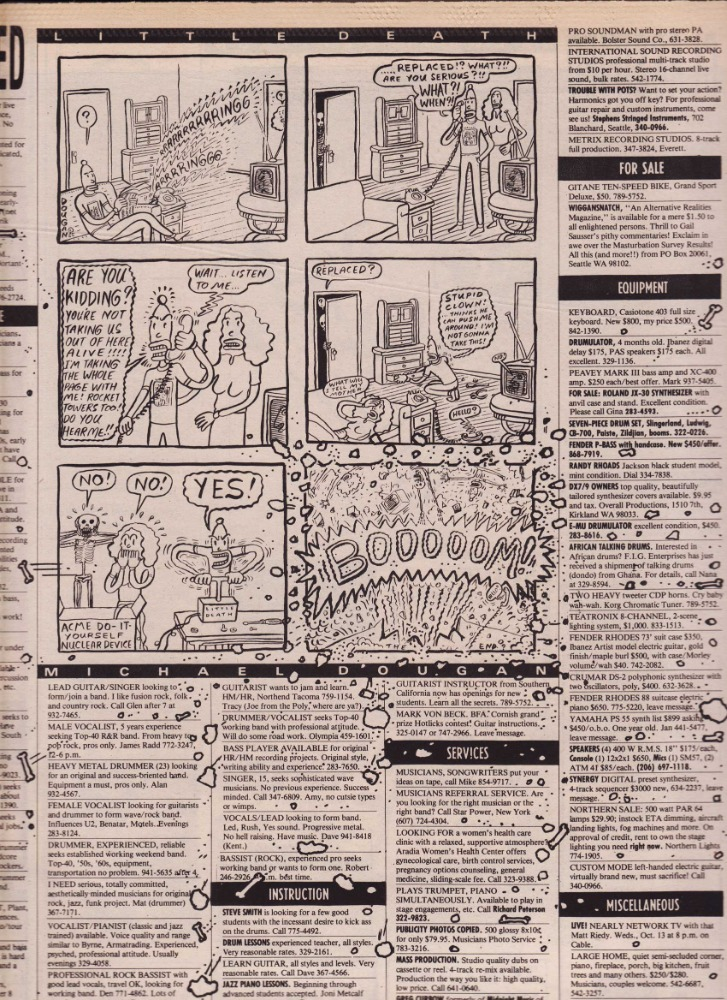

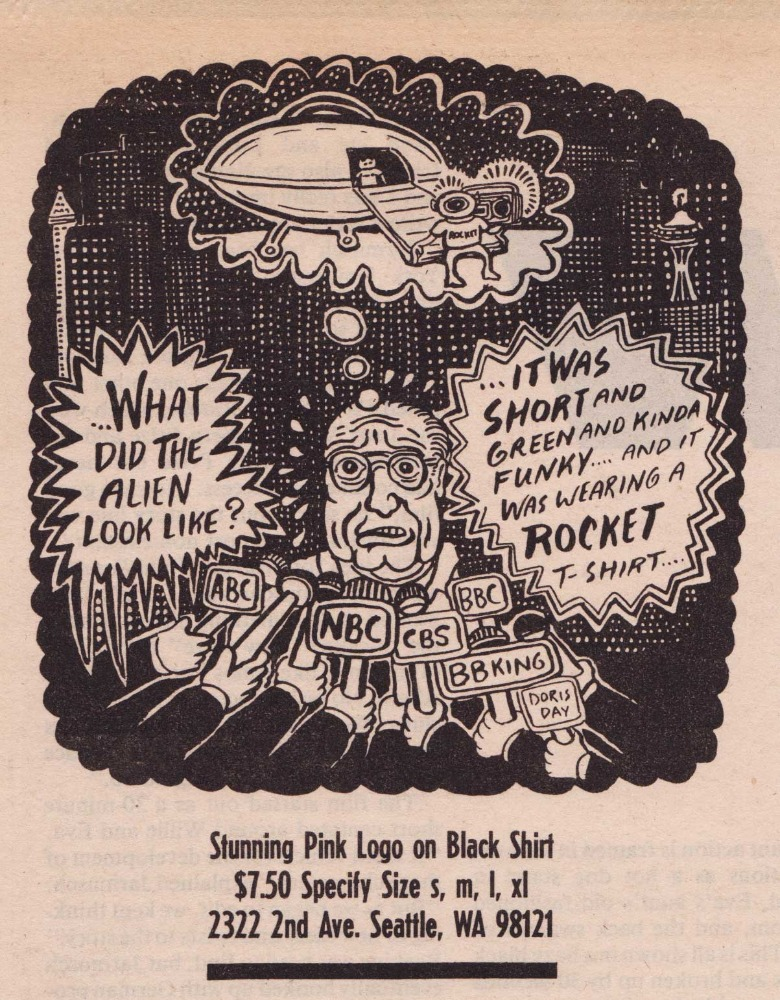

Though he later moved to focus on longer, more personal stories, Dougan's early comics were short and humor-oriented. He also did countless spot illustrations for the local Seattle free papers. At The Rocket, the city's legendary pop culture/music magazine that started as an entertainment supplement to the Seattle Sun, he did regular comic strips, illustrated articles, and sometimes even wrote articles.

"The Seattle Sun was around at that time," Dougan told Peter Bagge in an interview for the Seattle comics zine I Like Comics in 1993. "The Seattle Sun was Seattle's weekly newspaper that gave birth to The Rocket. I used to read that wherever I found it laying around, on a cigarette machine, in a coffee shop. That's where I saw Holly Tuttle's, Lynda Barry's strips. I thought, 'This is cool.' I'd been doodling cartoons in sketchbooks and stuff, but I didn't know what I wanted to do. I think the Seattle Sun might have been the first place I got something published. I did some cartoony illustration things for them before they died. This was in the early '80s when the Seattle Sun was this real liberal, hippy paper. I think The Rocket had just started. The Sun and The Rocket were split from each other.... The staff split. There was this trust-fund baby, liberal hippy, serious politics group, and there was the sex, drugs, and rock 'n roll group. The later folks thought, 'This is more fun. Let's write about this.'"

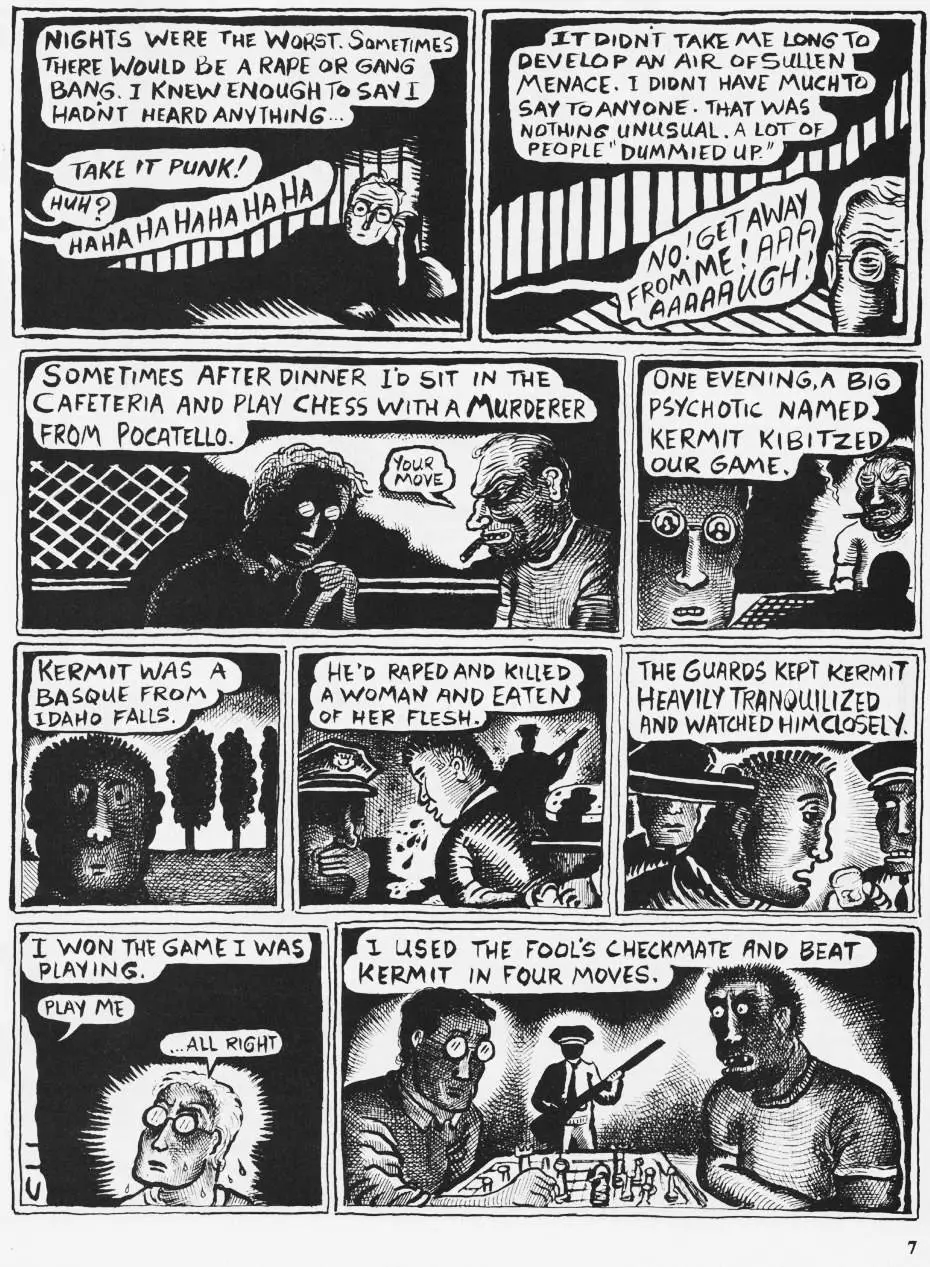

At The Rocket, Dougan worked with a series of talented art directors, including Art Chantry, Mark Michaelson, Robert Newman, Jesse Reyes and Kate Thompson, among others, as well as editor Charles R. Cross. He also worked with the writer Dennis Eichhorn, with whom he would be an early collaborator in autobiographical comics sprung from tales of Eichhorn's incredible sex and drug-fueled, often violent past. Their collaboration "Dennis the Sullen Menace" appeared in Weirdo #19. And while Dougan had already placed a few one-page strips in prior issues of Weirdo, this was his first long-form piece.

"I think that 'Dennis the Sullen Menace' was one of the first comic stories for Dennis, and it was certainly my first attempt," Dougan wrote in The Book of Weirdo. "I didn't know what I was doing! And doing everything the hard way. Conceiving it one panel at a time, and rendering the shit out of it. Using a combination of felt tip-pens, ink-and-quill, and a Rapidograph. Scratching away, and pasting each frame onto an illustration board. I hadn't discovered a brush yet, or page layout, or how to do comics.... But when I finally got it done, and Denny and I examined the final result, he was positively glowing with satisfaction.... He looked up at me and said, 'This is better than sex.' And he meant it."

In addition to Weirdo, Dougan's work began appearing in the anthologies Drawn and Quarterly, Centrifugal Bumble-Puppy, Prime Cuts, Zero Zero and Eichhorn's Real Stuff. In addition, as various art directors from The Rocket moved on to work for publications with a larger art budget, Dougan kept in touch, contributing illustrations to Entertainment Weekly, the Village Voice, the New York Times, and many others.

A number of attempts to expand into the world of television via animation projects came next, but none ever really panned out. One pilot project, The Dangwoods, aired on MTV's Liquid Television in 1993.

Dougan's experience in Hollywood was ultimately very frustrating. "When people in publishing tell you something, there's about an 85% chance it's true," he told Jon B. Cooke in a 2019 episode of Cooke's Subterranean Dispatch podcast. "When people in Hollywood or entertainment tell us something, there's almost no chance that it's true."

At some point, Dougan's work just stopped appearing in comics and magazines.

"Part of Michael's obscurity is because in 2006 a fire destroyed his house in Seattle, taking all of his art and archives—and in some ways his comics career—with it," Eric Reynolds wrote in his tribute. "He seemed to process what was a cartoonist's Worst Case Scenario better than most could have, but it also seemed to fuel a desire to move forward rather than look backward."

Nitta confirmed to me that the 2006 fire at their home in the Green Lake section of Seattle "ended up burning most of Michael's artwork... We salvaged some... That was after he came back from LA to work on a claymation project that Kit Boss ran [i.e. the short-lived U.S. iteration of Aardman Animations' Creature Comforts, on which Dougan was a writer; Kit Boss is a former writer for the Seattle Times and a writer/producer on television shows such as King of the Hill]. I was in Ireland on a business trip when that happened."

"I am not sure if that had any effect on Michael's decision about stopping or continuing with comics work," she said. "In my eyes, he was an extraordinarily talented cartoonist but his interest might have shifted to writing around that time."

So, what did happen? Why did Dougan stop doing comics? On Cooke's 2019 podcast, he said that one of the reasons was that, as he grew older, he found "being broke all the time was really hard."

"I was active for a period of 10 or 12 years and then faded out," he told Cooke. "And whereas some of the other guys endured and continued producing great stuff like Jim Woodring and Peter Bagge, and so on and so on, I sort of brushed the comics world for a while... why didn't I continue doing comics? A couple of reasons. I think one is... the medium that I fell in love with-- the idea of being an artist. I had a kind of romanticized idea of it, that a 10 year old kid would have, or a 15 year old kid... by the time I'd been [fascinated with comics] for 20 years, and dedicated that whole early part of my life to it, I was already coming to the end of that period. Whereas people that discovered [comics] when they were college age, they were still opening up new areas of it. And for me, I was starting to lose my way a little bit."

For whatever the reason, Dougan had decided he was finished with comics. In a 2021 Quora post, he wrote: "When you run out of gas, run out of ideas, it’s time to stop. Even if you could coast on recycled gags for decades more, and make piles of gold and silver, as [Charles] Schultz did, and his generational peers did, why carry on? What’s the point?"

In 2017, Dougan and Nitta moved to Tōno, Japan, a rural city Dougan told Cooke he loved for its history—"It's the oldest part of Japan"—and which reminded him of "the mythology" of his native Texas. "Tōno is this place that was also like that, it was a land of myth and magic," Dougan said. "The fairy tales of Japan... this is where they come from. The story of the kappa, and these ghost stories and all that. And I found that very engaging."

In 2018, the couple opened an American-style café in Tōno called Michael’s Cafe American, "across from the train station, next to the Tourist Information Center, in a quiet little agrarian community in rural Iwate [Prefecture]," Dougan wrote on his Quora blog, adding that the café was "the only American food joint in the region. If you’re in Iwate, and want American food, this is the place to go. We serve comfort food favorite[s] like pancakes, sandwiches, soups, cookies, brownies, and fresh roasted coffee."

According to Nitta, the café closed in December 2021, with plans to start a new business. Dougan was diagnosed with brain cancer in February 2022.

In addition to his wife, he is survived by his sisters, Leah Christine Tucker, Susan Beverly Wilson, Donna Jean Ducey and Leslie Faye Scott.

* * *

What follows are some memories about Dougan's life and work from some of his Seattle colleagues.

Peter Bagge

(cartoonist)

So here I am, writing yet another tribute for yet another great cartoonist who died way too soon. It’s reached a point where I’m thinking "okay, who died today?" every time I log onto Facebook…

I met Michael Dougan shortly after I moved to Seattle in 1985 or so. I saw his comics in the Seattle Rocket—these short wordless comic strips featuring some weird ghost/clown-looking character—that I found funny and charming, so I asked the editors about him and was soon introduced. Mike was an easygoing, unflappable fellow that everybody liked. He also used to live in the cheapest accommodations he could possibly find. The first one I saw was this old office directly above a downtown porno theater that had no kitchen or bathroom. He would simply give himself a sponge bath in that floor's shared restroom when everyone else went home. Whatever works! He didn't seem to mind it at all either, though he gradually moved into more upscale hovels that were at least quipped with such exotic luxuries as sinks and stoves.

I along with others started to encourage Mike to take his cartooning more seriously, and he soon was producing some of the best autobiographical comics the world has ever seen. At the time I failed to recognize just how good he'd become. I'd just think "nice work, Mike!" It only was more recently that I became cognizant of how strong it was. His body of work holds up extremely well - so much so that I was flabbergasted to learn that all of it is out of print! Somebody rectify that quickly, please!

Mike and I socialized regularly until about 2000 or so, when he suddenly seemed to disappear. He still lived in Seattle, but I never ran into him anywhere, nor did anyone else we both knew. I managed to track him down about 10 years ago - we had coffee somewhere and he seemed to be the same as ever. But he also seemed fine with being out of touch—and of not being a cartoonist anymore—so I left him alone after that. I had no idea he opened a café in Japan (of all places) until years after the fact. I hope his final years were happy ones. I’ll just assume that they were.

Art Chantry

(art director at The Rocket)

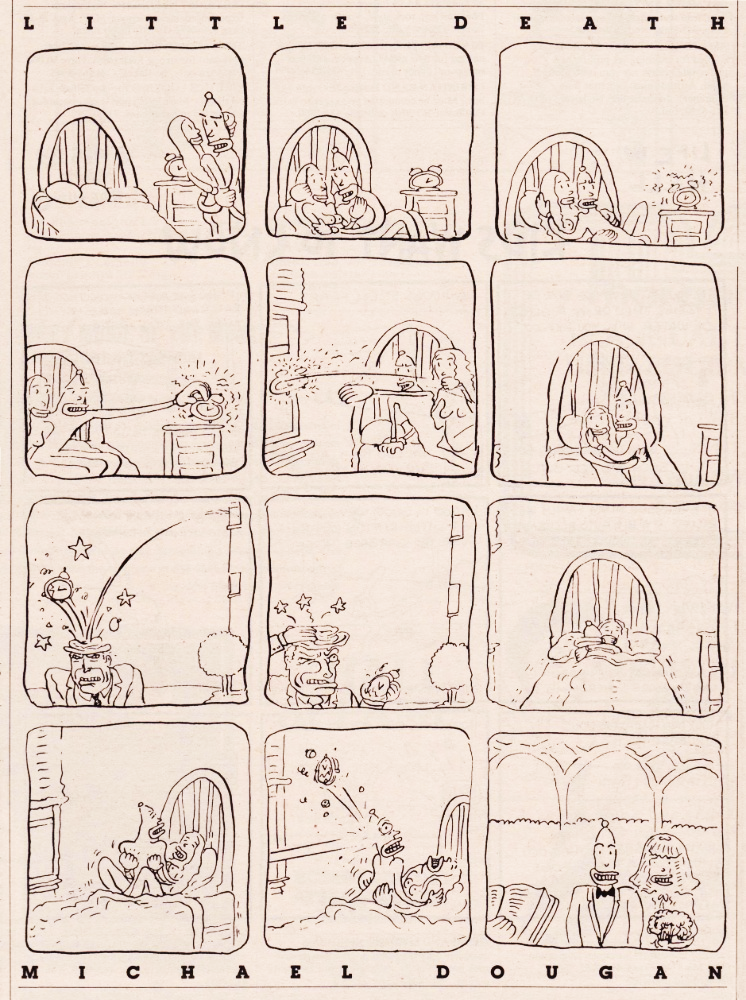

I met Michael when I first started working at The Rocket in 1983. He came in and hustled me to run his comic called "Little Death". It featured this weird alien clown-like character who never spoke. But he would always manage to tell a wonderful surreal little story - sorta like Henry meets David Lynch. I could see that he could write.

As time went on, everybody would encourage him to write dialog and story structures for his strips. Soon, he was coming in with his 'East Texas' stories - mostly autobiographical (as was the fad at the time). That stuff was magic. He became the best cartoonist we had at The Rocket (in my personal opinion). And THAT was really saying something (we had GREAT comix at The Rocket).

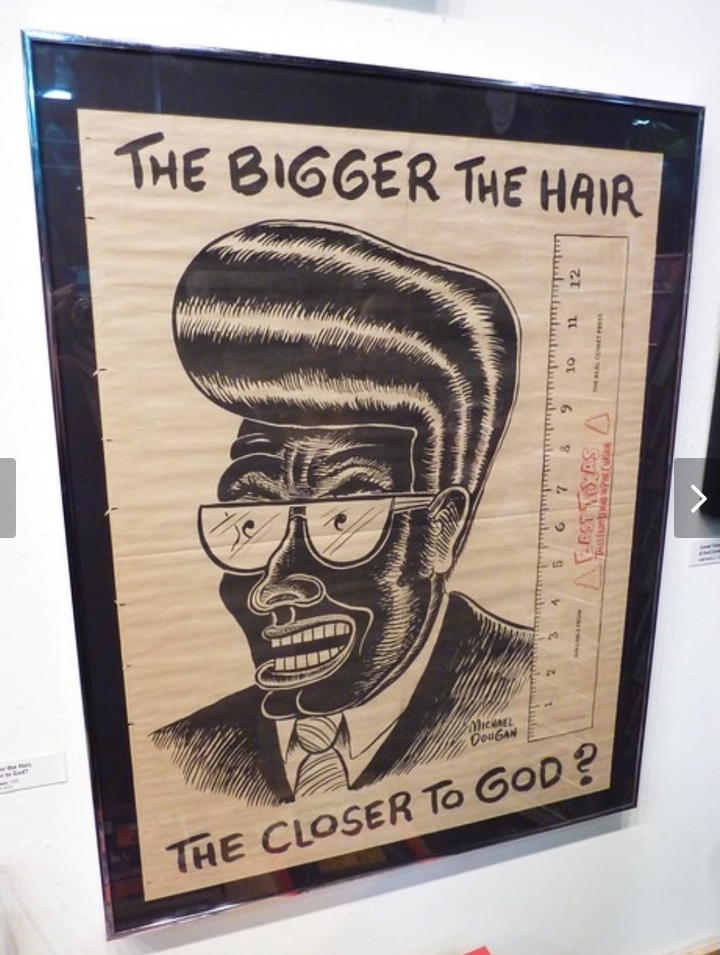

I got the opportunity to design his East Texas book (for Real Comet Press) and that was a huge learning curve for me (and for him). We both worked on continuity and dynamics and pacing in the story selection. We both realized we were working on a cartoon Spoon River Anthology. The result is a classic.

Robert Newman

(art director, editor at The Rocket)

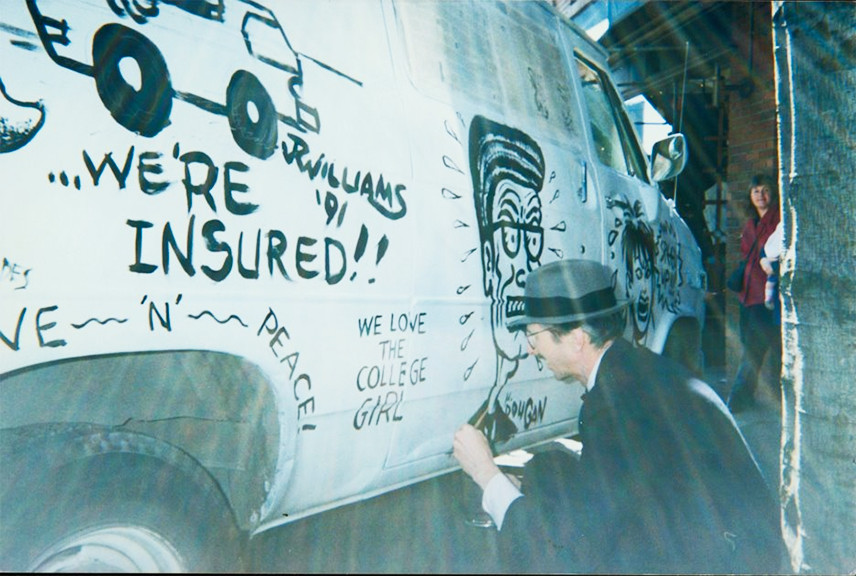

From the moment he materialized on the Seattle '80s scene, everyone loved hanging out with Michael Dougan. He was funny, smart, loyal, a good listener, and seemingly fascinated by everything anyone said... all the qualities that made him a very good friend and running buddy. Dougan was also always up for an adventure, whether it was meeting Dennis Eichhorn and I every Friday night at The Rocket office to watch the latest episode of Miami Vice (heavily lubricated by some of Eichhorn's latest stash) or shooting handguns at a target range in Woodinville with Robert Ferrigno and myself (we literally had to tell Michael, "Yes, dude, it is loaded!"). He had a sharp eye and ear and a keen memory, all of which, combined with his powerful drawing skills, made him a masterful visual storyteller who blazed a trail of brilliant comix and illustrations that influenced and inspired generations of graphic artists who followed him. Dougan had warmth and charm that were miles long, and more than anything else, I'll miss his smile and the twinkle in his eyes when he told (or heard) a great story.

Charles R. Cross

(editor at The Rocket)

When I think of the visual style of The Rocket, I think of Michael Dougan's ink lines which so defined the look of our magazine for two decades. He was everywhere in the paper, illustrating record reviews, and doing his brilliant cartoons.

Dougan was one of the most gifted cartoonists and illustrators of that era. I worked with him on so many projects at The Rocket and outside it. He could illustrate anything, but his real gift was in how his comics used storytelling. There was always humor, and pathos, and his style was unique. He was also one of the nicest and most normal cartoonists you would ever meet.

Larry Reid

(manager, Fantagraphics Bookstore & Gallery)

The last meaningful professional interaction I had with Michael was in 2012 when his work was featured in a retrospective exhibition I organized at Fantagraphics Bookstore about Cathy Hillenbrand’s Real Comet Press, an esoteric but important Seattle imprint that published his book East Texas as well as early work by Lynda Barry, James Turrell, Lucy Lippard, etc. By that point Michael rarely appeared in public but was warmly received at the opening. I remember he was extremely reluctant to discuss his situation, though he was cheerful and told everyone he was doing well.

I first met him about 20 years earlier when he was among a talented roster of writers, graphic artists, illustrators, and cartoonists associated with Seattle music monthly The Rocket. In the early '90s, Michael was a central figure in an informal salon of writers and artists that met monthly at The Crocodile café. (I sometimes attended, and recall that Peter Bagge, writer Kit Boss, and designer Art Chantry participated.)

Towards the end of that decade some of Michael's colleagues (like cartoonist Ron Hauge and Kit Boss), moved to LA and became remarkably successful working in television (thanks largely to Matt Groening, I believe). Michael soon joined them, but I don’t think it worked out as well for him. He mentioned a project [with the actor Billy Bob Thornton] that didn't come to fruition. I don't recall details, but the experience seemed to frustrate him. He returned to Seattle only to have his studio catch fire, resulting in the tragic loss of his artwork. After that he would occasionally drop by the bookstore, but other than that I seldom saw him.

Kate Thompson

(art director at The Rocket)

Michael was a mensch. Perhaps the best story he ever told was about not being paid by a big magazine (I don’t recall which one, or perhaps he never disclosed it), and so in frustration he went to their offices, took off his coat, and told them he would take off another article of clothing every five minutes until they brought him a check. Apparently he didn't get much past his sweater vest before he got paid. "Nothing scarier than a middle-aged naked guy," was how he put it.

I've known Michael since the mid '80s, where we met at The Rocket and then other pubs I worked at. He wasn't one to disclose too much on the super-personal side. I think the fire was a life game-changer for him: the Universe suggesting it was a time to skew in a different direction. Life took us on other paths after he went to Japan, and I have great regret we weren't in touch. He came to a gathering at our place in 2017 and was his usual ebullient self. I will miss him.

Jesse Marinoff Reyes

(art director at The Rocket, the Village Voice, Guitar World, etc.)

I think the thing I could say about Michael that's not exactly funny or wild, but shouldn't go unsaid, is this: how absolutely professional and disciplined he was. He's spoken, as others have, on the fly-by-night (literally) nature of working on monthly and weekly newspapers. That crazy "fill this space, quick!" on publication deadline days when the paper was about to go on press was a training ground that Michael embraced, perhaps better than most. When I got to NYC, there were loads of monster talents, but you'd be surprised how few had that last-minute ability to perform.

Michael was also absent the kind of outward insecurity around other cartoonists that I'd noticed (fairly uniformly) from cartoonists in general. It varies; the guys who were more experienced as illustrators were pretty good, or had outgrown it. But in the underground, I guess there was this fear of being eclipsed or something. Also a bit of pettiness (I won't name names).

This little work story kinda sums up both his can-do spirit and his lack of outward insecurity. He DID have insecurity, but you'd tend not to notice as he was so outwardly generous and welcoming. But there was this one time, I'd hired him to do a teeny spot illo - but I needed it in color, and he and some other cartoonists had success doing the illustration in a format similar to an animation cel: where the line art was shot on an acetate, then painted "behind" the acetate. That way, the color didn't interfere with the line art's sharpness or solidity. Well, Michael was having trouble and turned in something else. It was fine, and ran per normal, but I was just a little curt with him on the phone as I was up to my ears in deadline. Michael took this as I was annoyed with what he'd turned in.

Despite the fact that by this time I'd been around Michael for maybe 5-7 years, both socially and professionally, Michael STILL worried I might be upset with him. So the next thing I knew I received the following missive, that he artfully crafted to resemble legal documents - an "out-of-court settlement agreement" for an adjustment to his fee (and considering the amount involved, it's hilarious). All hand-rendered in his familiar handwriting (typos noted, including my name; no "i" in Jesse). I think, despite my playing along, I had him paid the intended space rate, not the "adjusted" fee.

I miss this guy.

Lynda Barry

(cartoonist)

Ever since I heard [about Dougan's death], I've found myself remembering the last time we saw each other, which was at least 30 years ago. The thing is, that 'last time' is at least three different memories. One of them is he and I dancing in a near empty bar in Seattle to "Will It Go Round in Circles" by Billy Preston. I was going through a bad break up and he was making me laugh so hard.

We met in Seattle when we were still in our 20s. He was from East Texas and the first things I every knew about East Texas came from his comics. I took to him so quickly, was knocked out by everything about him, from his comics to his truly remarkable friendliness. He was so hilarious and gorgeous and so original and gifted as a cartoonist. When I look at his work now, in 2023 I find it's just as fresh as it was when he made it. His comics look like they could have been drawn last week. He was the sweetest, most open and least cynical cartoonist I knew and very much ahead of his time.

I'm trying to understand and believe the news that he's gone but as soon as I consider it, it just bounces away and is replaced by another memory of him.

But dancing with him to Billy Preston and him making me laugh so hard and feel so wonderful is the one memory I'm hanging onto the tightest right now.