On January 23, PBS’ acclaimed Independent Lens series began streaming the documentary No Straight Lines: The Rise of Queer Comics, which details how “[f]ive queer comic book artists journey from the underground comix scene to mainstream acceptance.” Inspired by the Lambda Literary Award-winning 2012 anthology edited by Justin Hall, the film—directed and produced by Peabody Award-winning filmmaker Vivian Kleiman—is its own creation, featuring the voices of many cartoonists but focusing on five in particular: Alison Bechdel; Jennifer Camper; Howard Cruse; Rupert Kinnard; and Mary Wings. Attention is paid to how their work and careers in some ways mirror the changing landscape around queer culture in the United States.

On January 23, PBS’ acclaimed Independent Lens series began streaming the documentary No Straight Lines: The Rise of Queer Comics, which details how “[f]ive queer comic book artists journey from the underground comix scene to mainstream acceptance.” Inspired by the Lambda Literary Award-winning 2012 anthology edited by Justin Hall, the film—directed and produced by Peabody Award-winning filmmaker Vivian Kleiman—is its own creation, featuring the voices of many cartoonists but focusing on five in particular: Alison Bechdel; Jennifer Camper; Howard Cruse; Rupert Kinnard; and Mary Wings. Attention is paid to how their work and careers in some ways mirror the changing landscape around queer culture in the United States.

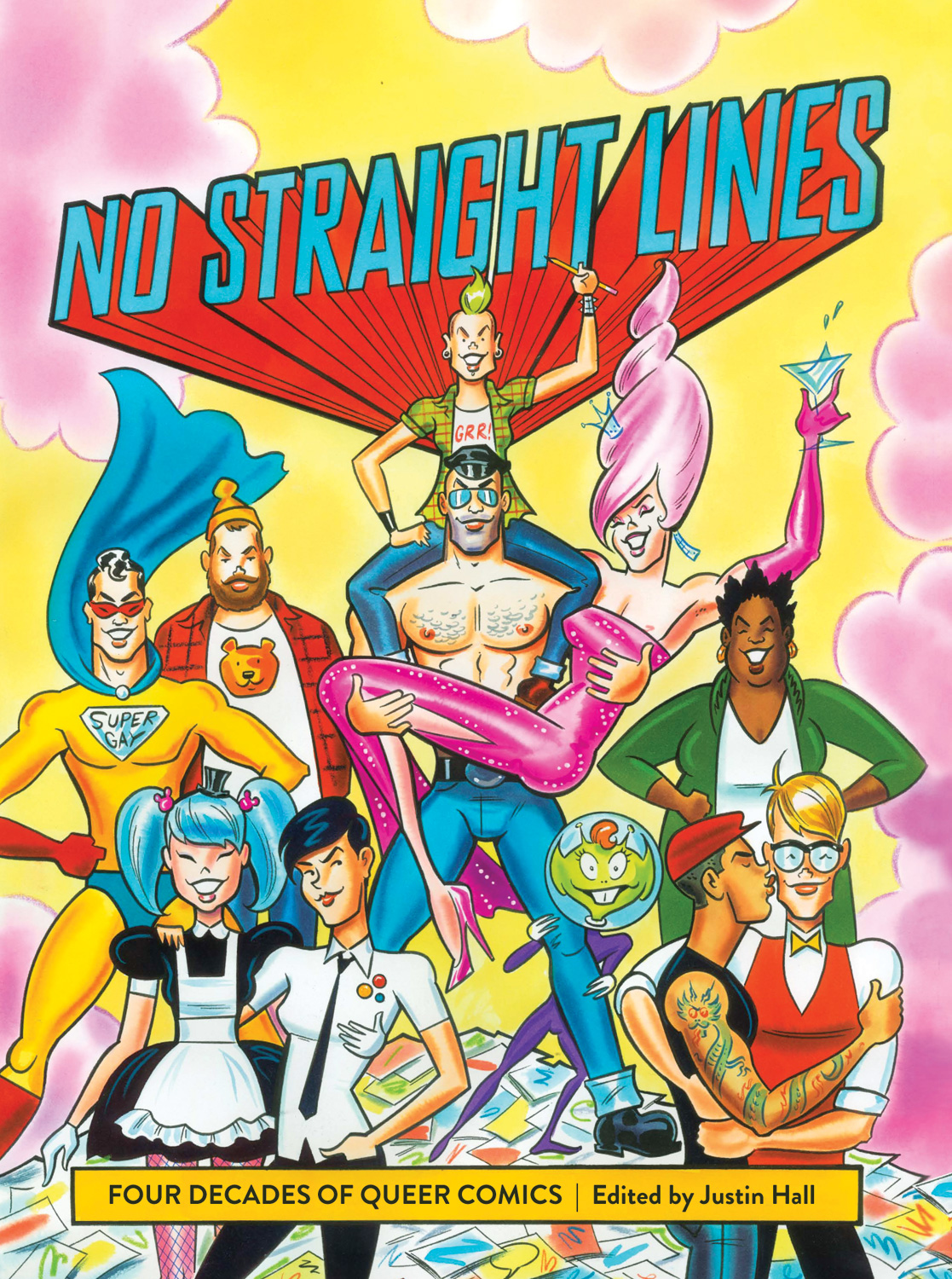

In an editor's note for the anthology, Hall wrote that his ambition was to assemble “the definitive anthology of queer comics” - a failed mission, admittedly, because the topic was impossible to encompass in a single volume. Nonetheless, the book included a wide range of work from artists across the decades, demonstrating how queer comics often operated in a very different space than the rest of the medium. Where comics about rape and racism were acceptable–even venerated–queer topics and creators were often unwelcome.

Hall is currently Chair of the California College of the Arts' MFA in Comics program; he has also been a Fulbright Scholar, and was a producer and consultant on the film, which premiered at the 2021 Tribeca Film Festival. Producer/director Kleiman is a documentarian with a long list of credits, including projects with the late filmmaker Marlon Riggs, whose works were collected by the Criterion Collection in 2021. I’ve known and spoken with Hall and Kleiman for many years; Hall and I have met at numerous comics events, while Kleiman and I first met at the initial Queers & Comics Conference in 2015. I’ve interviewed both in the past, and I am thrilled to be able to talk with them again now that the film is in wide release.

No Straight Lines is streaming on the PBS website and on PBS Passport through April 22.

-Alex Dueben

ALEX DUEBEN: Justin, this started with you. Tell me about the anthology and putting it together all those years ago. What made you go, let's assemble an anthology of queer comics?

JUSTIN HALL: I realized from the moment that I began making comics in earnest, selling them at conventions, and engaging with the comics community, that there was this profound separation between LGBTQ comics and the rest of the comics world. At the same time, the insular world of queer media that had always supported queer comics (the queer publishers, gay and feminist bookstores, queer newspapers, etc.) was collapsing in on itself and the entire history of queer comics produced within it was in danger of disappearing.

As a way to showcase and help preserve this work, I pitched a show to the SF Cartoon Art Museum back in 2006. They jumped at the idea, and I curated the first museum show of LGBTQ comics. We wanted to create a catalogue of the work, but funding fell through. The idea of a proper book percolated in my brain for several years as I became increasingly involved in queer comics, met more creators, and became more aware of its history. Eventually I pitched the book to Fantagraphics, and they bit!

I ran a class on queer comics where I teach at California College of the Arts, and I used the course reader as a sort of preliminary version of the book. This was an important step, as I got to see which stories resonated with the students, and I swapped out a number of the stories because of that feedback. We also brought in various creators for filmed interviews, which in turn prompted a friend, Dan Zeitman, to suggest to me the idea of a documentary film.

Now, neither of us had ever actually made a film before, so we didn’t really know what we were doing! We spent a couple of years showing up at comic cons filming folks - but none of that footage was ultimately usable. Eventually, Greg Sirota, a film professional who has an executive producer credit on the film, came on as Dan pulled back, and we then were able to do the preliminary interviews and put together a trailer.

Greg ultimately had to pull back from the film as well, but by that time Vivian was onboard as director and producer. And Vivian is the real deal as a filmmaker! She had the vision, filmmaking skills, and tenacity to make the project happen. I stayed on as producer, and the two of us worked together for the next six years on the film.

Vivian, how did you get involved with the film and what interested you in the topic? What was your experience with and knowledge of comics before the film?

VIVIAN KLEIMAN: Justin had teamed up with a filmmaker named Greg Sirota to make a documentary film based on the anthology he edited, No Straight Lines. After some initial filming, it was clear they weren’t getting traction with fundraising, and subsequently asked if I wanted to take on the project. Quite frankly, I hesitated because pretty much the extent of my involvement in comics was Alison Bechdel’s Dykes to Watch Out For when it was serialized in the '80s in the local [California Bay Area] feminist newspaper Plexus.

It was really when I attended the first Queers & Comics Conference in NYC that I was all-in, and I saw that queer comics was a subject that would engage me: from people who have compelling stories to tell, and a world that I thought I knew something about but really didn’t. The artists I met that weekend represented the panoply of who we are as LGBT people. They were such good storytellers, and they had a treasure trove of images to choose from. Moreover, when Howard Cruse delivered his keynote presentation, I knew it was the outline of a film: beginning with his roots in Alabama, followed by his mainstream work as a Madison Avenue graphic artist, then his emergence out of the closet as editor of Gay Comix, and then a long-term relationship with his partner, and finally to an Eisner Award-winning artist. It was a story of queer history in America through the lives of artists who were marginalized in the underground comix scene and ultimately found mainstream acceptance.

That’s a dramatic story of challenges faced and overcome - which is a really good recipe for a fascinating story.

How did you initially think of the film? What pieces were there from the beginning and what changed as you worked on it?

KLEIMAN: For me, filmmaking is more interesting when it’s about the emotional lives of people rather than who-did-what-when or an intellectual analysis. I want to reach the viewer first in the heart, and then the brain. I had a certain set of stories that I was curious to cover, which included: How did they come to be a cartoonist? How did their work evolve? What obstacles did they encounter? And how did they overcome those challenges?

To achieve that goal of taking the viewer on an emotional experience–much like a novel–I limited the film to a profile of five artists. With roughly 10 minutes per artist, plus breathing room, those stories would quickly occupy 60 minutes of a feature-length film. I also was quite clear from the get-go that the film would start in the underground comix scene in 1973 with the publication of Mary Wings’ Come Out Comix, and end with Alison Bechdel’s triumph of Fun Home in 2006, [with it] landing on the cover of Time magazine as Book of the Year.

But at one point as we were editing the film, I watched a rough cut and thought the work lacked a “welcome mat” that would make a younger viewer care to watch it. So, I conjured up an experiment - to film “speed interviews” with a dozen next gen artists, and try to weave that unusual aesthetic element into the filmic approach that was already in place. Well, it took many, many attempts at moving the stories around, but finally we landed on a structure that worked.

As you said, the film centers on five cartoonists - Alison Bechdel, Jennifer Camper, Howard Cruse, Rupert Kinnard and Mary Wings. And I wonder if you could talk about why these five and what they and their work mean?

HALL: Initially, the idea was to look at queer comics over history. But later, as Vivian and I narrowed in on the final form of the film, it became increasingly clear that we needed the focus to be tighter. We settled on the pioneers of queer comics, which gave us a generation of creators to work with. Rupert created the first continuing Black queer characters, Jen was always a pillar of the community as well as an artistic powerhouse, and Howard and Alison were always going to be in it, as the biggest names in the field.

As a filmmaker, Vivian understood that we also needed to have people who were good on camera and who were engaging in terms of their personal stories. She’s an excellent interviewer and really drew those stories out when we filmed with the artists. On top of that, she had the idea to bring in the “Greek chorus” of younger creators to comment upon and provide context for the “main characters”. I was teaching in the MFA in Comics program at CCA at that point, so we were able to bring in a number of our alumni and faculty to be interviewed, which was really special.

We first met at the Queers & Comics Conference, and I'm curious what role that setting played in making the film. Because throughout the film you have short interviews with younger creators, and I can't help but think that you were very conscious of making not just a tribute to older artists and their work and lives and journeys, but conveying a sense of the community that they helped to foster and build.

KLEIMAN: Simply put, the queer comics world is a delightful community.

And yes, I was not at all interested in doing a hagiographic tribute to older artists. Instead, I wanted to braid a few themes:

- One part portrait of five scrappy queer comic book artists;

- One part four decades of queer life in the US;

- One part the story of a DIY art form, often considered junk food for kids, but now the vernacular of next gen-ers that has also found its way into literary studies;

- One part the evolution of queer publishing - from a simple offset press in the basement of a women’s karate studio, to every city having a local feminist newspaper, and finally to mainstream publishers with queer titles.

There are a number of moments in the film which stand out, like Howard Cruse and Denis Kitchen talking about the creation of Gay Comix, or some really emotional moments with Jennifer Camper and Alison Bechdel. I know that you've spent years and watched these hundreds of times, but what stands out for you? What are the moments or days that you remember?

KLEIMAN: Although the funding for the film came in small amounts, one indulgence was to fly the amazing cinematographer Andy Black to each location. But the benefit was that he knew the story and he knew the artists. Andy and I shared a similar aesthetic and approach to documentary filmmaking, and we shared similar ways of responding to the surprises that present themselves when in production. One particular day when we were in Brooklyn filming with Jen Camper, at one point she became overwhelmed with emotions as we revisited the trauma of the AIDS epidemic. Suddenly she jumped up and left the room, sobbing with grief. Without a word spoken, Andy continued to record video, while our veteran sound recordist Judy Karp followed suit and continued to record audio. A full minute later, Jen returns, and we continue to record our conversation. That full minute of the camera trained on the empty chair is a moment of powerful emotional resonance that I kept in the film in its entirety. No cuts. When I showed the film recently to a community college class, and asked if I should cut out that long moment, the response was a unanimous and emphatic “No!” So, it’s a wonderful example of how powerful storytelling captures the viewers hearts - even the generation known for a low attention span.

Now I have to ask: who drew the panel borders, the captions with people's names, and those elements in the film?

HALL: We used a font created from my hand-lettering for the captions and at other points in the film. We also had the wonderful fortune to work with the amazing Suzanne Slatcher on the animations and art direction.

KLEIMAN: My friend Suzanne Slatcher is the talented art director who did most of the animation and graphics for the film. The notion of using a black border was an idea that I had after grabbing one of Alison’s compilations of Dykes to Watch Out For. The cover had the black border used to signify that this is an anthology of comics. And suddenly I thought, “Well, if Alison can use this trope, so can I.” And so began the evolution of an effort to construct a filmic approach which is somewhat informed by the subject of the film: comics.

What had to be changed or edited to appear on PBS?

KLEIMAN: After all the big commercial streamers including Netflix, Hulu and HBO rejected the film, I was approached by Lois Vossen, executive producer of the national PBS series Independent Lens, offering the film a coveted slot in that prestigious series on primetime national TV. The deal would require conforming the film to FCC regulations since PBS is a broadcaster, not merely a streaming service. [After getting] approval from the five main artists to blur exposed body parts, who saw the prospect of reaching 2-3 million viewers worth the “cover up”, it was a long and painful process to add “digital fig leaves” over parts of the comics. And in some instances, since the entire panel would be covered, it made more sense to select a different panel from work by the same artist.

I flat out rejected the conventional approach, which is to lightly blur the images and try to not distract the viewer. Au contraire. The PBS digital fig leaves that I created are bold, and are designed to resemble the LGBTQ Rainbow flag whose fully saturated colors immediately prompt the viewer to understand that this is a version of the film explicitly made for a primetime broadcast audience.

Vivian, I’m curious how you see the film in conversation with your other work?

KLEIMAN: When Marlon [Riggs] set out to produce the landmark experimental documentary Tongues Untied, he had a very specific audience in mind. This was to be a film for black gay men. At every junction he made a conscious decision: any material that seemed to be expository, or explaining the black gay experience to an outsider, was removed. Marlon was only including that which contributed to a conversation among black gay men. As a result, the film was infused with a vitality and rawness and directness that otherwise would have been diluted. And in the end, it served to invite outsiders to have a glimpse into their lives.

Not to compare No Straight Lines with that triumph of filmmaking, but the lesson of deciding on a specific audience, and making editorial decisions in service of that specific audience, is the Big Lesson that helped me shape No Straight Lines. I knew I wanted to reach young viewers. When I filmed those “speed interviews” with a dozen next gen artists, and included them as a sort of “Greek chorus”, it was a divisive element. Test audiences over the age of 50 criticized their inclusion, stating that if they were in the film, I needed to provide the viewer with more information about these next gen artists. It was distracting to just have them pop up in the film once in a while, with no context or background. But test audiences under the age of 30 got it. and wondered why the heck I was asking about it 'cause there was no issue to worry about. They got that the snippets of comments are compelling, and no more background contextualizing was needed. At all. And that’s how the final film was edited.

Now Justin, the book No Straight Lines cannot be a decade old, because that would mean we've known each other for a decade - and neither of us are that old. But you mentioned that you're putting together a new 10th anniversary edition of the book. What is going to be different and why?

HALL: Well, even if we’ve gotten older, I don’t think either of us can claim to be any more mature!

But yes, I’m working with Fantagraphics now to do a new edition of the No Straight Lines book. The world of queer comics has changed tremendously since it came out and we want the new edition to reflect that, even though it will remain a survey of work up to 2012, when the first edition was published. On top of that, I’m very pleased to say that the book helped inspire some wonderful academic research into the history of queer comics, so I want that to be acknowledged in this new edition.

I’ll be writing a new foreword reflecting on all of this, as well as adding a number of new pages of art that I wish I’d included initially. I’ll also be editing my essay on the history of queer comics at the beginning of the book using information I've uncovered since the first edition.

Justin, you've made comics over the past decade, but a lot of your work has been focused on promoting the anthology, the film, the Queers & Comics conference, you've been teaching - I hope that we'll see more comics from you over the next decade.

HALL: Oh yeah, I’ve been busy! I put out a collection of my erotic work with Dave Davenport, Hard to Swallow [Northwest Press, 2016], and an anthology of queer horror comics with William O. Tyler called Theater of Terror! Revenge of the Queers [Northwest Press, 2019], as well as some other smaller projects. I also created a series of large-scale comics posters installed in the bus kiosks along San Francisco’s main thoroughfare, Market Street, showcasing important moments in queer SF history. Currently, I’m working on a graphic novel for Abrams Books that incorporates that history alongside memoir of my own gay-ass life in the city.

But to your point, a lot of my time has been taken up with teaching and organizing. I’m now the Chair of the MFA in Comics program at CCA, and I was the first Fulbright Scholar of Comics, teaching in the Czech Republic. I’ve also been regularly teaching at a comics school in Denmark, organizing events like the Queers & Comics Conference with Jen Camper, writing academic work for publications like The Cambridge Companion to the Graphic Novel, and generally traveling around spreading the comics gospel.

Vivian, have you given any thought to a new project or something else you want to do? Or not do? We won't be too offended if you say that you're tired of hanging out with cartoonists.

KLEIMAN: Ha ha! I love the community of queer comics. The artists are dynamic, and creative, and engaged with the issues of the day as much as the usual questions of looking for love, or lost love, or tales of the gym.

Now when can I get a DVD of the film to add to my shelf?

KLEIMAN: Just as we released the film at Tribeca in June 2021, the world of independent documentary distribution entered a chaotic state of flux. Suddenly the usual outlets stopped handling new documentary films. We’re lucky to have a great educational distributor, GoodDocs.net, which licenses the digital film and DVDs for educational use: universities, museums, galleries, community organizations, etc. Now that we have the PBS broadcast launched, and the PBS streaming service is available, we’ll be setting out to make streaming and DVDs available for rental and sales to individuals.

Stay tuned, Alex!