Bastien Vivès has been causing a stir in the European comics scene over the last decade or so with his keen sense of character, fluid and loose drawing style, and ability to do effective work in a broad range of genres. (TCJ has discussed his work on the Prix-de-la-Série-winning Last Man here; included his A Sister in our best-of-2017 list here; his Polina on our best-of-2020 list here;, discussed his work with Ruppert and Mulot on the heist caper La Grande Odalisque here and here, and put it on our best of 2021 here; interviewed him here; reviewed his The Butchery here; and I myself reviewed Olympia, the sequel to La Grande Odalisque, here, and I’ll almost certainly feature it on my best-of-2022 list. He’s pretty good!)

In addition to his talents as a writer and storyteller and his ability to work in a wide variety of styles, Vivés is also absurdly prolific, and with La Grande Odalisque still fresh in the memory, the US publisher Ablaze now presents us with The Blouse, a much smaller and less ambitious work originally published in French in 2018. It manages, in its quiet shifts of mood and tone, to become something unexpectedly (almost shockingly) revealing, in a literal and figurative sense.

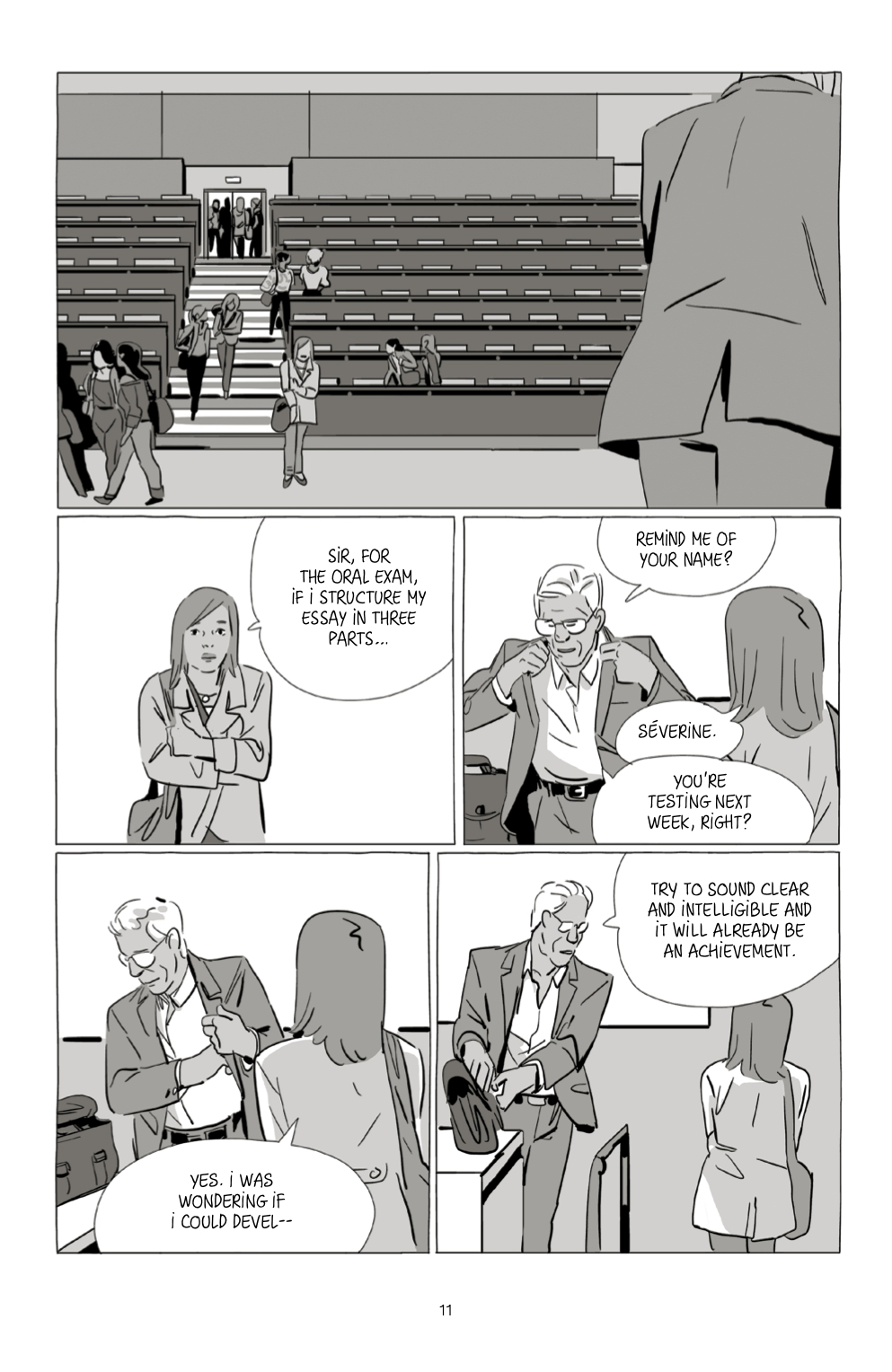

Séverine, the protagonist of the story, is a young student at the Sorbonne studying literature. She is a familiar enough type: bright and dedicated, but not especially gifted; pretty enough to navigate the usual social spaces but not enough to land a boyfriend who gives a shit about her; and, well, a bit of a doormat. Her situation, whether stemming from a lack of confidence or circumstance or something else–Vivès does not hold our hands through the book–is one that’s pretty familiar to a lot of women.

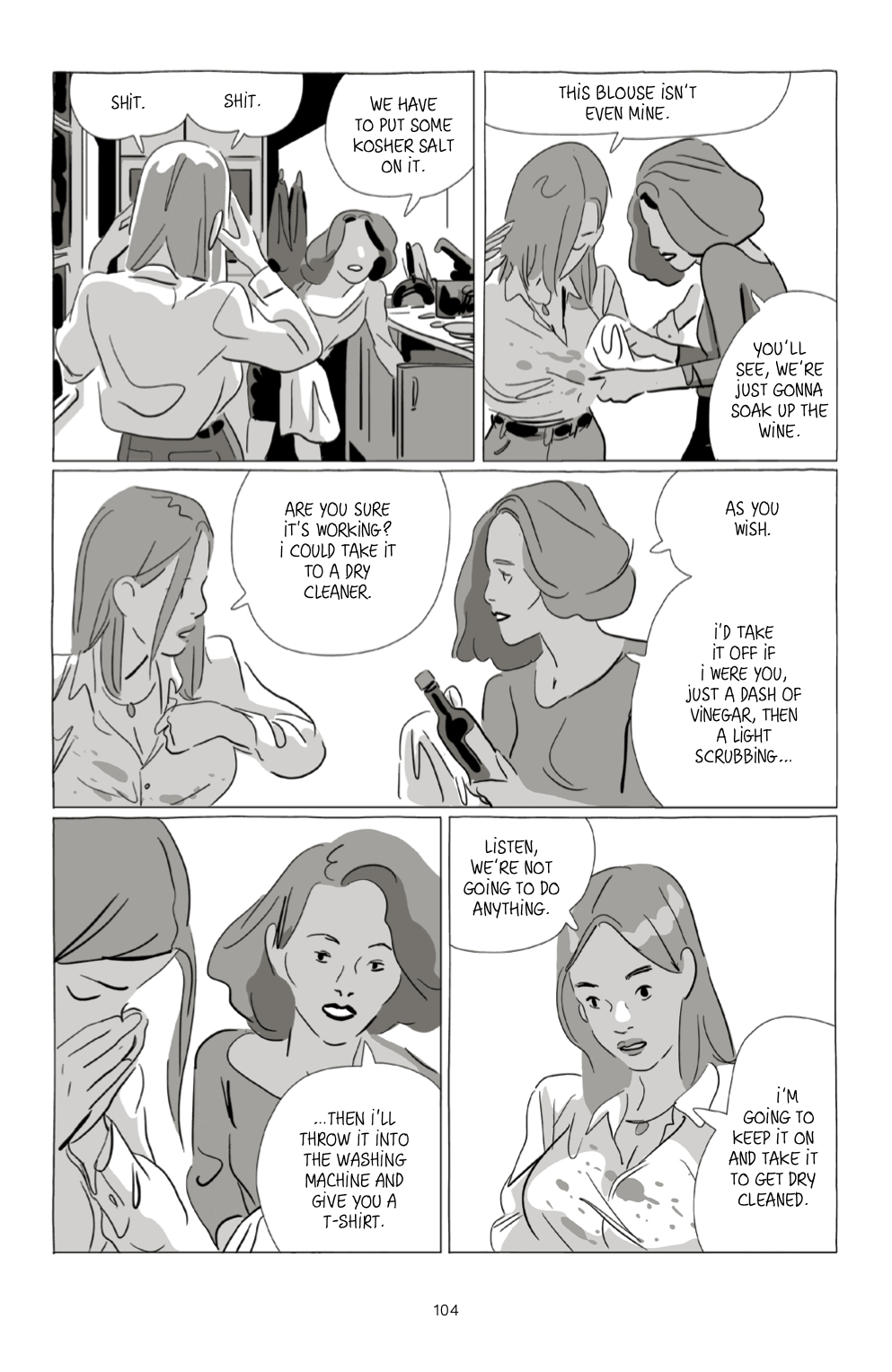

Men speak over her. Her opinions aren’t especially valued by her friends, her live-in boyfriend, or even her family. She struggles in class, not out of incompetence, but out of indifference. Nobody really seems to listen to her. She’s not a cipher or an enigma (though visually, she scans that way, because of her plain dress and Vivès’ habit of drawing people without eyes or mouths at certain moments). She’s just sort of there. Until, one night, she’s making some spare cash babysitting the curious daughter of an unhappily married couple, and the child gets sick.

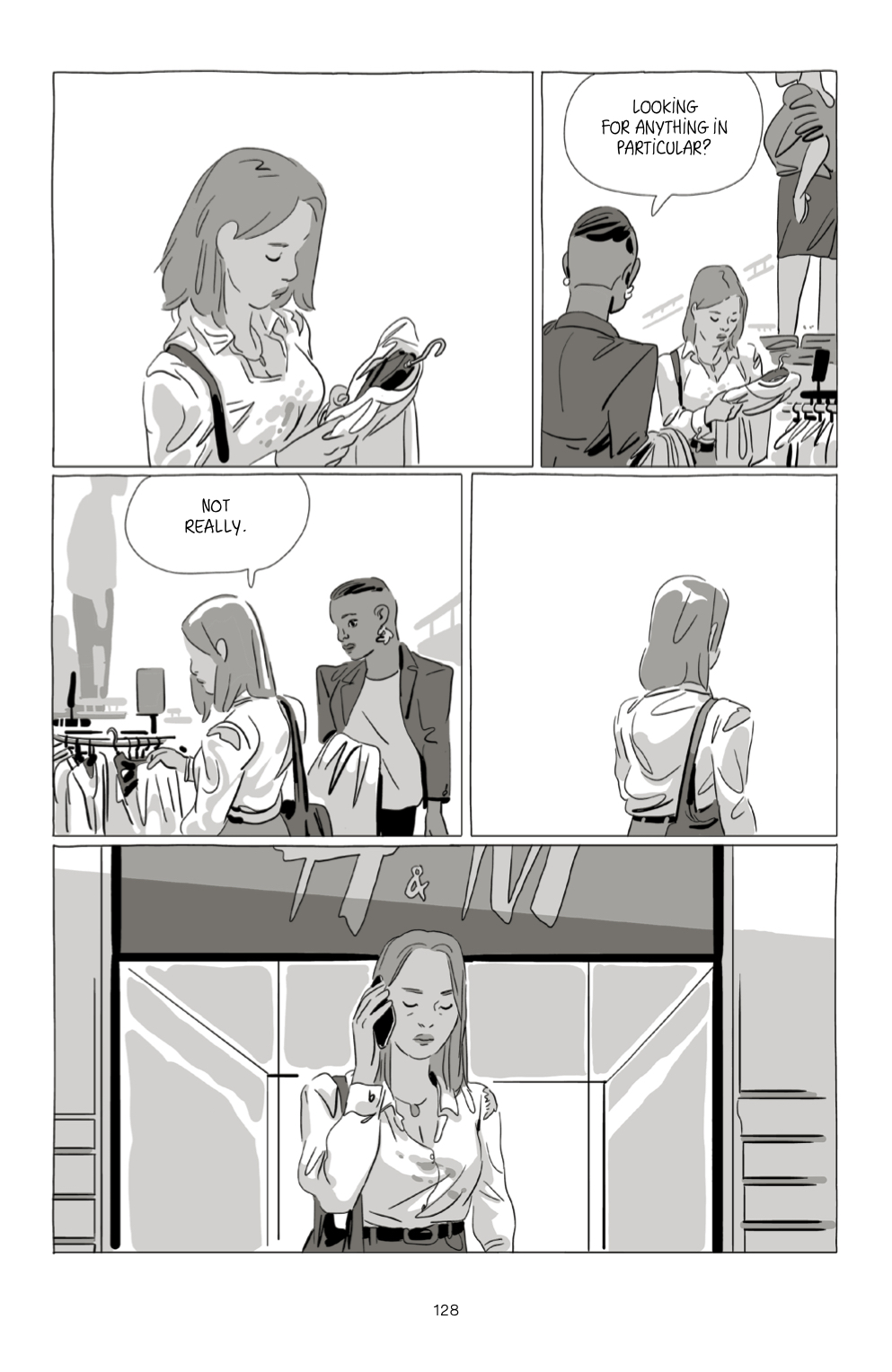

Before sending her home, the girl’s father hands Séverine one of his wife’s silk blouses to wear home, to replace the one his kid threw up on. The blouse has an immediately transformative effect on her: she becomes more confident; more attractive, internally and externally; more willing to speak her mind; and more sexual - both in frequency and intensity of desire. Other people notice too. Her literature professor, who previously overlooked her like everyone else, now praises her work as brilliant - and privately confesses his attraction to her. Séverine's boyfriend remains oblivious, but his friends don’t. She undergoes a complete transformation, all because of this one flimsy piece of delicate fabric.

Vivès wisely doesn’t give in to the temptation to explain any of this. Whether the blouse itself contains some kind of hypnotic power over men, or whether Séverine has simply realized the power she possesses as a woman, or whether it’s something else entirely, he declines to say. (This helps the narrative when it occasionally slips, as it does in much of Vivès’ other work, into the slightly uncanny.) Regardless of the why, Séverine comes to believe that the blouse itself has a degree of magic, and she intends to chase the feeling that magic gives her.

It's a remarkable story, with more than a few twists along the way, including an utterly strange and unpredictable ending, and more than a little intense, even unnerving, sex and violence. Vivès art is pleasantly reminiscent of how his work has progressed along the way; it bears little of his early faux-manga style, resembling instead the sharp linework of La Grande Odalisque and Olympia - as well as the excellent use of space and implication of motion he’s come to be so good at. It has almost a watercolor effect at times because of the washes of gray, though the black and white is often a bit flat on the page.

It seems almost impossible to talk about Vivès without comparing him to some film director or another. His cross-genre capabilities and cultural touchstones have aspects of the Coen brothers and Steven Soderbergh, but the visual palette, pacing, and perspective are entirely European. Though comparisons to Carax and Bresson are not mistaken in any meaningful sense, what The Blouse struck me most as was specifically Bresson's late period: all close-ups and movement, a determined sense of making every scene and every moment in the camera eye count, a minimalist’s ability to make something out of nothing combined with a neo-realist’s focus on the everyday infused with the sublime and the eerie.

What’s particularly striking about The Blouse is that way that it takes the notion of the male gaze and, while not exactly inverting it, shows it to us from so many different angles. Séverine experiences the attention of men in so many ways: indifference, lust, discomfort, condescension - and when she finally comes to understand the power of her own desire, and learns how to unleash her sexuality in an active and not a passive way, it is both liberating and menacing, thrilling and dangerous.

The Blouse has a few problems, most of them stemming from how thinly drawn all the characters except Séverine are (though, of course, it is her story). As much as it can resemble a classic of the French cinema, it can also remind you of an American independent film of the ‘90s, so caught up in its own ideas that it doesn’t quite gel for the viewer. But overall, it’s a terrific success, a surprising new direction from one of Europe’s most celebrated comics artists and someone who should start enjoying far more attention in the US.