He could see something beyond himself and he made a path to it out of art.

He could see something beyond himself and he made a path to it out of art.

Rachel Cusk on Cimambue (Cenni de Pepol) (c. 1240 - c. 1301)

“Between 1930 and 1945, Hitler and Stalin killed 14 million non-combatants in central Europe,” Large Victor said, the smoke from the cafe’s wood-fired oven suggesting forests burning. “That’s nearly 3000 people a day, every day, for 15 years. So, Ukraine, unless nukes...”

“Progress,” Goshkin said.

Dade walked into the café and handed me a lemon-orange, 32-page booklet of odd multi-colored drawings, spotted with odd words, a joint work from the mid-to-late ‘60s of a sextet of Chicago artists who, from the oscillating lines and melting shapes, the jarring chromatics and lingual nonsense, had sat through too many screenings of The Yellow Submarine. When I reached home, waiting was a brick-red, 68-page booklet of odd, multi-colored, wordless drawings, the product of a solo Chicago artist who may have been in the same audience, sucking on the same sugar cubes.

Dade had known nothing about the orange book, The Hairy Who Sideshow (1967), not even how he’d come to possess it. I had heard the name “Hairy Who” but knew nothing about them.[1] I had received the red book, Sketchbook of an Artist (2022), because I had promised to review it. But I had known nothing about its creator, George Hansen, except that, in the early ‘70s, he had received a cease-and-desist letter from Albert Morse, Robert Crumb’s attorney, because Hansen’s style too closely resembled his client’s, and I had only known that because, nearly a decade before Dade reached my table, I had written about Albert and Robert.[2]

By the time you reach 80, I thought, you have cast enough lines into the sea that you can not be surprised what you haul in before breakfast.

I.

There came a point on Goshkin’s daily cardio-walk when he could look west and see the bay, Mt. Tam, Golden Gate bridge. He made it a point to stop and recognize the wonder of his being there. Shortly before that view sat the white stucco home of a Turkish-Yugoslavian ceramicist, who filled her front yard with larger-that-life kings, angels, beasts, and combinations thereof.[3] Recently she had added an umbrella stand-like piece in whose bowl were the words:

the past is gone

the future is a miracle

the present is a gift

that’s why it is called

“present.”[4]

She had come from Macedonia to deliver and he from West Philadelphia to receive this message in North Berkeley.

George Hansen was born in 1951 and grew up in Uptown, a Chicago neighborhood of bars, transient hotels, and Appalachians whose coal mines had closed. His mother took in sewing until he and his sister became old enough to look after themselves. Then she worked outside the home, eventually becoming a dental assistant. His father, an artist in advertising, came in every night, took off his jacket and tie, sat down at the dining room table with a beer or two, a cigarette or two, and vented.

Hasnsen decided early that work, for him, would be a means, not an end. Most of his jobs would last a week or month. He never took one with “career” in mind. “Idiot jobs,” he called them. “All idiot jobs.” The supervisor he hated the most, he locked in a trailer truck. The guy ended up in St. Louis.

Hansen wanted a life of music and drawings.

Music had been in his air from day one.

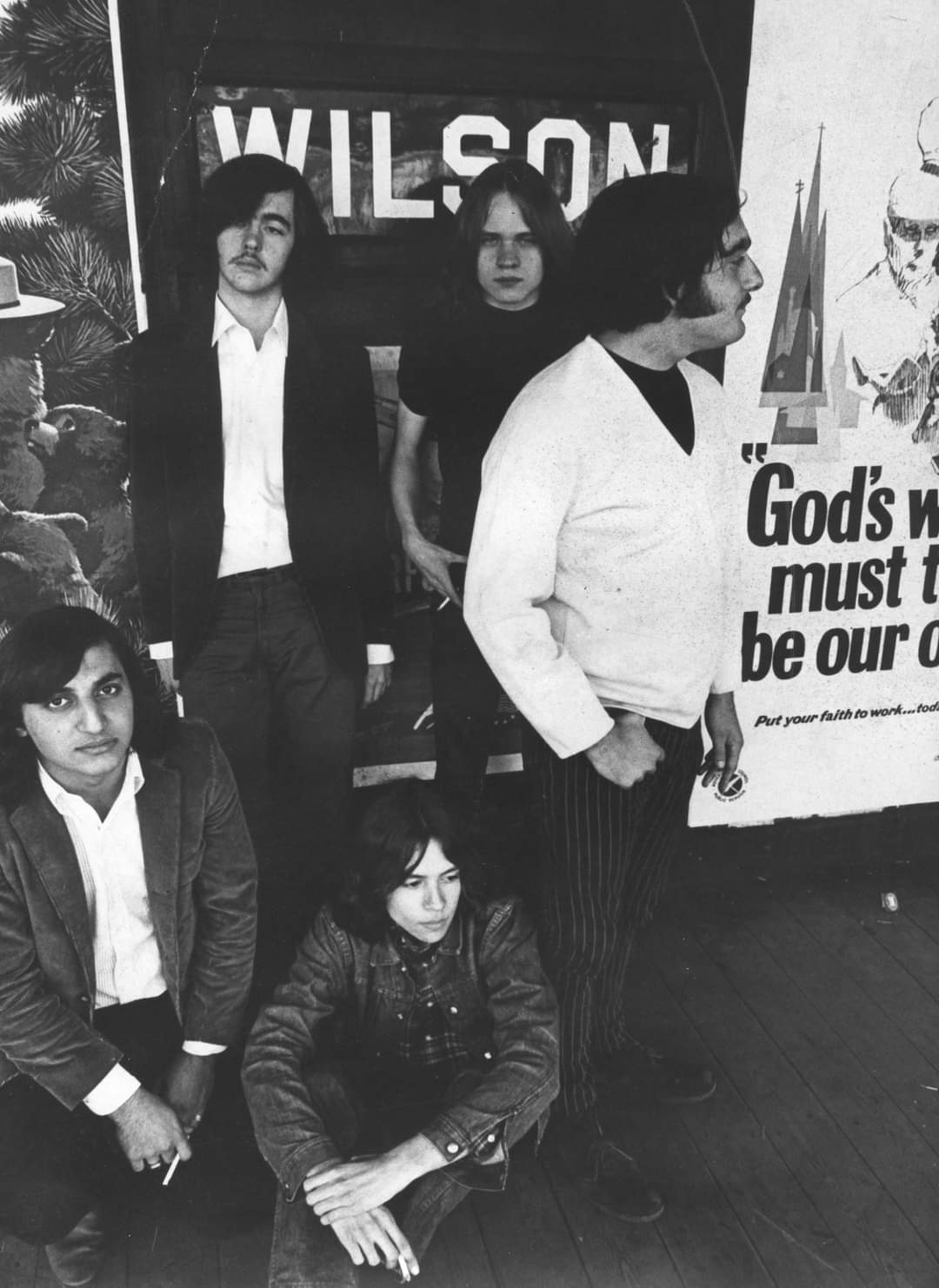

His family had no TV, so radio brought in blues, country, gospel, R&B. His grandfather played piano, an uncle upright bass, his father guitar. Hansen would play guitar, banjo, mandolin, ukulele, harmonica, piano. By his early teens, he was playing in clubs, at parties and street fairs. The gigs were mainly rock, but, not liking to play note-for-note, he didn’t last with any band for long. He fronted his own band – a “million” of them – but, tired of thinking of clever names, he just called them The George Hansen Band.

His first shot at “national exposure” was the Yippies’ “Festival of Life,” in Lincoln Park, the weekend before the 1968 Democratic Convention. “When I got there with my guys I asked who was gonna pay us and this guy said we should talk to Sinclair[5] and as soon as I asked John he said with a big stoned smile, ‘No one’s getting paid’ and I said, ‘What are you talking about?’ and he said, ‘Everything’s for free’ and I said ‘What the fuck are you talking about?’ and he said, ‘You know, everything is for free’ and I said, ‘Well who’s gonna pay the guys who are lugging my equipment around and pay for my gas and all my other things’ and he just said, ‘Everything is free’ and I said, ‘Yknow what? Fuck you.’ I told my guys to re-load the van and we left.”[6]

Hansen had begun to draw “as soon as I could hold a crayon.” His inspirations were cereal boxes, “Pogo,” “The Spirit,” Saturday Evening Post, and, once he discovered reprints, “Mutt & Jeff” and “Krazy Kat.” By 12, he was free-lancing in advertising, selling his own comics to classmates, being paid by them to draw birthday cards for their parents, and swapping and selling fanzines. Art school, he decided, offered less than learning on his own.[7]

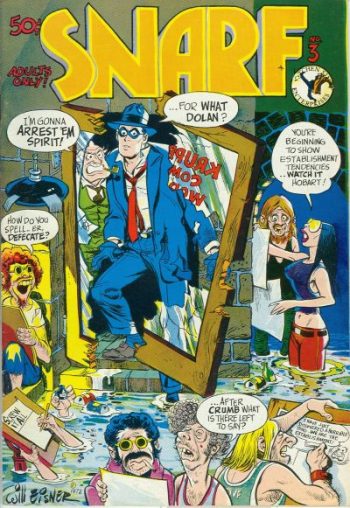

Hansen saw the first Zap when playing a gig on the West Coast – and recognized that similar artists had influenced Crumb and him. Back in Chicago, in the Hippy enclave of Old Town, he spotted other UGs, including Bijou #1, with work by Jay Lynch, whom he knew from fanzines. Doing your own comic, without editors limiting what you wrote or drew appealed.

Between 1971 and 1973, Hansen did eight solo books. The ones I found[8] did not scream “Crumb!” to me. (Legalese-ly speaking, I saw no likelihood of consumer confusion.)[9] Oh, there were schnozzolas the size of feet and strutting feet the size of salamis, but there were eight-balls and eyeballs, floating unanchored to pool tables or craniums, and free-flowing abstractions and panel lines zig-zagging or absent, which sang of Moscoso or Williams or Griffin too. (I also spotted licks copped from Herriman and Wolverton.) So Hansen absorbed Zap, I thought. What was wrong with that? Artists absorb artists and writers absorb writers – or observations on walks – or thoughts that pass through their heads on these walks. Crumb himself has said that LSD connected him to EC Segar and Billy DeBeck, transmitting to him the wisdom within the absurdity they captured. That is how art works. You learn from others and you make your own.

But the UG establishment reacted like Hansen was Pat Boone aping Little Richard. Gary Arlington”s distribution company refused to handle his books. Bill Griffith cited him as a prime example of the inept drawing and objectionable content that was destroying the UG. (“Pissed me off,” Hansen says. “I thought Griffith’s skill level was a lot below mine. Just godawful.”) Historians of the era essentially wrote him out of it.[10] He became, Zeno, an ex-editor of mine e-mailed: “the Randy Hensen of comix – the poor guy got reamed by the UG scene, essentially blackballed for being the best Crumb clone in a field of Crumb clones.”

II.

Grosbeck held the Chron’s front page chest-high like a cross warding off demons. “By 2050, Vermont will not have enough snow to ski. The Colorado is fucked. And don’t get me started on Nepal.”

“I do not wash my car,” Large Victor said, biting his scone. “My garden can return to fucking nature. Go-Go, you see your doppio porquitos on any Endangered Species List?”

Half the café still wore masks. But, Goshkin thought, we have lost more folks to Alzheimer’s, cancer, hearts. Each time he saw someone he hadn’t, he thought, We need, like, reverse Amber Alerts to periodically beep,“I am still around.”

Hansen’s books were, of course, not Ulysses but, as Theodore Sturgeon said... And they have an impressive simplicity and directness. They may even have had influence. Hansen did not butcher babies, but he, arguably, cleared a path for Mike Diana.

His comix splashed like children in mud. They were dirty and fun and mommy and daddy disapproved. The more repellant acts he committed to paper, he seemed to have thought, the more valuable his work became. So Bobby Fuckstick and Peter Pussyeater ran over children at play in the street and used one another for toilet paper. Rarely does much I work on in public make me anxious about people peeking over my shoulder, but I was a tad uncomfortable to find myself jotting down “jism” so frequently and parsing its implications.

Which is itself worth crediting.

Still, the “freedom,” which attracted Hansen to the UG, seemed to have been limited to the sexual and scatological. Certainly, politics was not in play.

“Funny you should bring that up,” he said, when we spoke, “because, 50 years ago, me and Crumb were sitting around talking about some contemporaries and I asked him what he thought of Skip Williamson and he said he didn’t like his stuff and I said ‘Why not’ and he said, ‘All this power to the people shit. What’s Skip talking about? He works for Playboy.’ I couldn’t endorse any of the politics that came up from ‘66 into the ‘70s. People were always talking about tearing things down but they never talked about what they would replace it with.

“I never was a hippie. I mean, I had long hair. I was a typical Chicago greaser and, with the Beatles, you had to shift with the times, so we took the grease out and when your hair’s already long, with a duck tail and all that, it only takes a few months before it gets down to your shoulders. I was part of what used to be referred to as ‘longhairs.’ The whole hippy thing, I could never relate to. I couldn’t relate to their music or clothes or political beliefs or anything.”

I hesitated. “So who’d you vote for, McGovern or Nixon?”

“McGovern. Don’t get me started on Nixon.”

If headline worthy issues were absent from Hansen’s comix, they did express a consistent philosophical drift. The world, he declared, was “lousy,” and everyone “out t’ screw you,” and life “cold an’ ugly an’ lonely...” “It’s all garbage,” he wrote, about which you can’t “do nothin.’”

These were pronouncements unseasoned by or ungrounded upon much. Hansen, at 21, 22 was a bird broken from its shell, beginning to chirp. Every creative person, I thought, does this at every age attained, figures now they have things understood. Now the world should listen. But these books occupied only a thin slice of Hansen’s life. He had far to go to reach his now.

III.

“Shot himself in the heart,” Grosbeck said.

“He had a gun?” said Goshkin.

“Or a bow and arrow,” said Large Victor.

“We talked every day or two. Whatever he needed. Should he kill himself? Should he kill his wife? She had dementia and totally dependent on him.”

The sun was on their table. A car alarm sounded.

“Except she wasn’t. She didn’t know he was there. The executor puts her in a home. She’s happy as a clam.”

“So not killing her was the right answer,” Goshkin said. Just steal it, he thought of the car.

“Six-thousand a month. What happens when the money’s gone?”

“Put her on an ice floe?” said Large Victor.

“If there are any ice floes,” Grosbeck said.

Which brings me to the product at hand.

Hansen has been filling sketchbooks for 60 years. He sketched at home, at work, in public until he tired of people asking if he was an artist. He would say, “No, I’m a cartoonist,” but that led to other conversations of which he did not wish to be part. Now, he wakes, has coffee, and begins. He can go until evening.

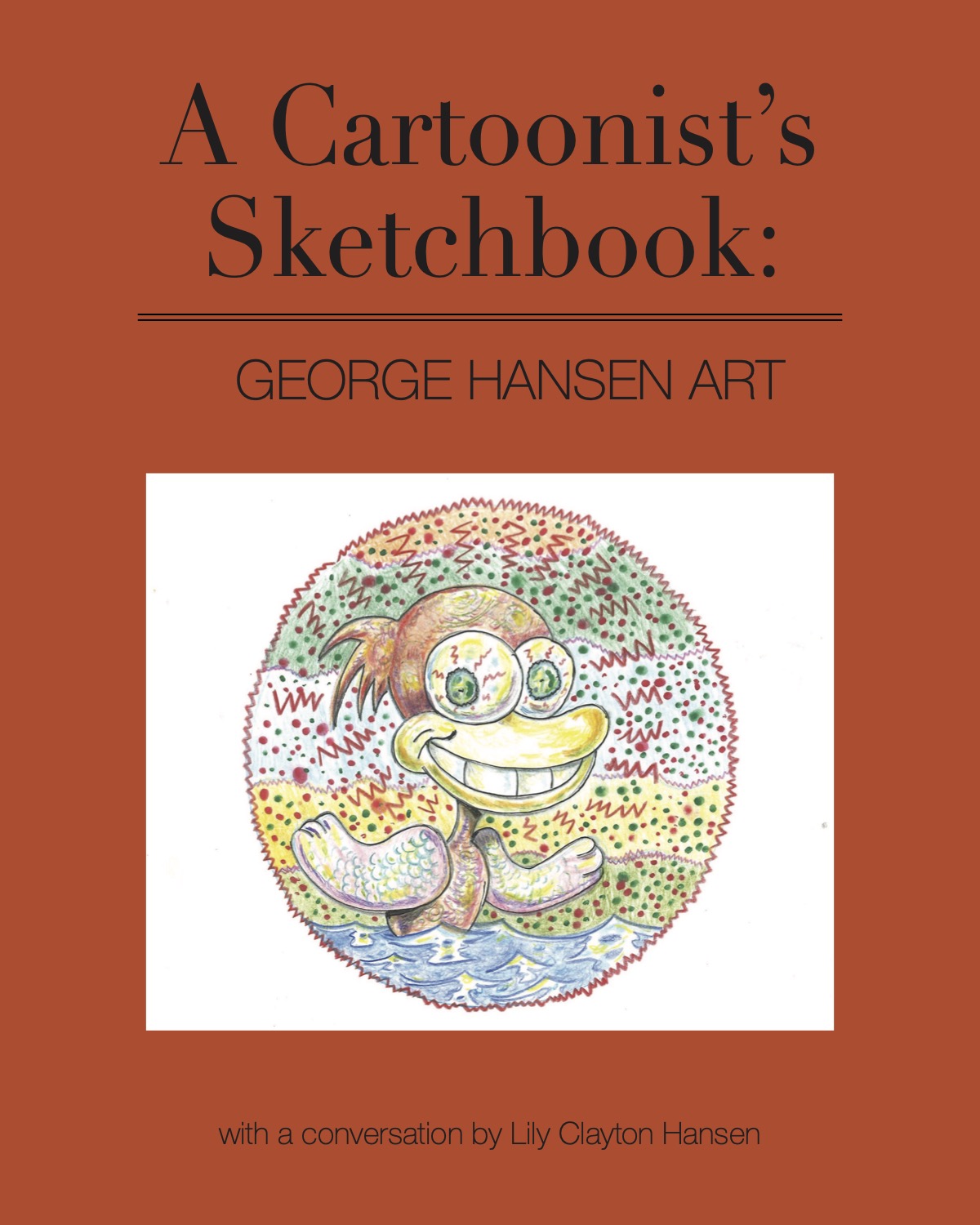

Sketchbook is a tribute to her father by Lily Clayton Hansen, an actor/writer of Ashville, NC. It holds more than 100 colored-pencil drawings, selected from two of his books from the last five years. Men, women, dogs, cats, ducks, elephants, bears, woodpeckers, crows wolves, pigs smoke cigars, wear hats, drive cars, swim, strut, pilot spacecraft, talk, squawk, swim, play ukulele and trumpet. They do not behave in a way of which anyone would disapprove. They do not challenge a single norm. They express no bleakness.

Their smiles are broad, their grins toothy, their eyes HUGE. (You can cover their face, except for the eyes, and know their emotions.) They usually present individually, encircled within a frazzled line. They are rendered in muted reds and yellows, greens and blues, some brown, never a black. They exist upon ponds and grass and softly clouded, sunny skies. It is never night or shadowed – never dark. Very few of Hansen’s creatures are glum or apprehensive; only one bawls. Almost all radiate positivity, uninhibitedly express joy. They seem to have tumbled from a clown’s car of early animation. (I caught genetic-ties to Felix and Goofy – even a hybrid of Groucho and his Bet Your Life duck.) They seem a symphony of fun, a rhapsody of delight. It is, at first glance, a world of soap bubbles blowing by, though, considered long enough, if you bend toward cynicism, those eyes – pupils dilated – sclerata charged with the zig-zag reds of broken capillaries – may hint at madness.

His goal, Hansen stated was “to always make (the animals) happy.” If only the rest of us would, Lily concludes, “focus... on forgiveness and humor,” like him, the world would experience less “violence and pain.” By the time you reach 80, I thought, such an expression carries the impact – and portends the endurance – of wet sand dribbled onto castles at the ocean’s edge. On the other hand, why not? If we must walk around with thoughts in our head, why should they not be rosy? It is not like they determine when or where the next meteor strikes.

Hansen’s own view seems inner directed. “I truly believe,” he says, “regardless of whatever your craft is, that you just do it until you don’t have a breath left in you.” Which seems to recognize within each person a “self” that should be allowed full expression. The world may benefit – or it may continue on its own way, wherever it is headed – but those heeding Hansen will have a shot at fulfillment within their time’s allotment.

Sketchbook is a book worth buying. Have your eyes take it in and allow your mind to ping-pong it about.

Ruth explained that Rafael Nadal’s ability to focus came from his rituals. His tics before each serve. The arrangement of his bottles at each change-over. They helped him shut out the noise from the crowd, the weight of his family’s presence, the pressure of the match. They allowed him to focus on the point at hand.

We have our rituals too, Goshkin said. My time at the café. Our cardio-walks. The lying-in-bed together, reading, watching TV. The bed was a life raft on which they bobbed in the troubled ocean.

The writing each morning.

[You can see more of George Hansen's work here, and the book is available here.]

[1]. Dan Nadel’s “Forms of Life,” in The Collected Hairy Who Publications (2015) informed me that the Who were six Chicago art school graduates, who exhibited collectively between 1966 and 1969. To economize, they created “comic book”catalogues, with each artist riffing on – and defying – the genre’s conventions: content previously foreign to it; narrative obliterated by random, surreal imagery and “poetic observation”; each book costing a buck (plus $.25, if mail-ordered), seven-times a Fantastic-Four. While not X-rated, it didn’t require a diseased imagination to discern sexual imagery to suit most tastes. “Grotesque,” “transgessive,” and “challenging social norms,” Wikipedia added. UG comix, which hit the stands about that time with their own designs on the norm-challenging market did not interest it. And the UG seems to have operated ignorant of the Chicago Six. When two members met Crumb and S. Clay Wilson, it was, Nadel wrote, “awkward” for all concerned.

[2]. The Comics Journal. 302.

[3]. See: https://www.berkeleyside.org/2015/07/14/how-quirky-is-berkeley-buldan-sekas-ceramic-friends.

[4]. Google attributes this quote to Eleanor Roosevelt and says it begins “Yesterday is history. Tomorrow is a mystery...”

[5]. John Sinclair managed the MC-5, the one “name” rock group to appear at the festival. A “revolutionary” poet and founder of the White Panther Party, the possession of two joints earned him a 10-year jail sentence in 1969.

[6]. Hansen would record and toured with some of his groups. He toured with legendary Delta bluesman Honey Boy Edwards. He even founded – and still owns – his own label, Bloody Music Records, which began recording blues artists but, once blues became “a white man’s game,” shifted to free jazz.

[7]. He would go on to illustrate magazines (Midwest, The Chicago Reader, The American Literary Magazine), LP covers (Flying Fish, Earwig, Pearl/Belmont), and concert posters. He has story-boarded stop-motion animated ads and created art for t-shirts. Now galleries sell his work.

[8]. Hard Times, Like Nobody’s Bizness, Choice Meats (#1, 2)

[9]. If there was confusion, at least at eBay, it was between him and Doug Hansen, one of whose books I ended up with after it was peddled under this mis-labeling.

[10]. A limited scan of my limited resources show Hansen MIA in Sabin’s Adult Comics, Duin & Richardson’s Between the Panels, Rosenkranz’s Rebel Visions – even the “Chicago” section of his Artsy Fartsy Funnies – and Estrin’s History of Underground Comics while others, whose names have gone unuttered in public since, march through its pages in boldface type.