Smahtguy: The Life and Times of Barney Frank by cartoonist Eric Orner tells the story of the longtime Massachusetts Congressman who was a leading voice of progressivism and one of the most prominent gay politicians in the country. Frank was an unlikely figure to become such a powerful politician, especially given when he grew up. Born in 1940 to a working class family in New Jersey, he attended Harvard and became Chief of Staff to the Mayor of Boston at a young age before running for state legislature and then US Congress. During his decades of public service Frank was a colorful character, but he was a focused and thoughtful policy wonk, interested in legislating and governing above politics.

Orner has been making comics for decades. He spent fifteen years drawing the beloved comic strip The Mostly Unfabulous Social Life of Ethan Green, which ran in newspapers across the country and was collected in numerous books. After a long time spent working in animation and a few years working for Congressman Frank, Orner has finished his first graphic novel. This is a book that finds politics compelling, that dramatizes congressional hearings and makes them exciting and interesting, in ways that show what a talented writer and artist Orner is. If Ethan Green showed that he was interested in longer narratives and continuing storylines, Smahtguy hopefully marks the first of more books to come, and feels like the work of an artist who is only getting started.

* * *

Alex Dueben: You mentioned that you worked for Congressman Frank and I’m curious where exactly this book started?

Eric Orner: Drawing is what I do. I started out as an editorial cartoonist for a daily newspaper. I made a comic strip – The Mostly Unfabulous Social Life of Ethan Green – that was published in LGBTQ newspapers and city alt weeklies for years. I worked in animation and did some storyboarding at Disney. On the other hand, politics, government, law—that’s what my family does. There have been times in my life when my business—drawing—wasn’t paying the bills, so I turned to the other, my family’s business. And the political day job I held longest was staffer in Massachusetts and on Capitol Hill for Barney Frank. He and I also share a lot of Boston roots. Both of us came to the city to go to college, and law school, and stayed to start our lives. Him in the 60’s and me in the 80’s. He represented Southeastern Massachusetts in Congress, which is where my mom’s large family is from. So we have a lot in common – Smahtguy grew out that.

Where did the idea come from? Because this is different from the work that people know you from.

I don’t keep a diary, but I do fill up a lot of sketchbooks, that are sort of like illustrated diaries. And I did so during the many years I worked on Barney’s staff. About four years ago Barney and I had a cup of coffee in New York, and he mentioned that he wished the biographies of him in print were a little more colorful. I think originally, he wondered if I might be interested in writing one myself – as my day jobs have often involved writing. I wasn’t interested in writing a book of prose – I’m not a trained biographer by any means. But quickly my wheels started to spin, thinking that I’d enjoy doing a graphic book about him. And knowing I had all those old sketch books that chronicled my time as his aide, meant I had a ready source for inspiration and storytelling. To make a long story short, Barney is well acquainted with my cartooning. He put up with it off and on for a lot of years. (Drawing a queer comic strip wasn’t your average side hustle for a Capitol Hill staffer). I don’t think he was completely surprised when I offered to draw it.

In this day and age – especially in the gay community – we look to some very brave examples of activists as our heroes. But folks working the more mainstream side of politics, they don’t get as much attention. Barney was doing a lot of hard work. And to me, a lot of heroic work. Particularly for LGBTQ rights. I thought it made sense to try and raise the profile of that work in a way that younger people might appreciate.

So when you said you could draw the book, he didn’t go, no!

No. And I didn’t say I would draw it immediately. But then I went home and I started to think about many of the political stories floating around my head, some of which were in my sketchbooks. I thought about my appreciation for many of the landscapes on which his life has played out. I’ve spent a great deal of time in all corners of Massachusetts, not just Boston. I’m a citizen of gay America. And I was one of his aides in Washington. If somebody was going to draw his story, I was well positioned to do it. That’s what went through my head. And when I realized that a publisher would buy it, well, that helped. [laughs]

How long were you working for him?

Ten years off and on. I used to be embarrassed about the convoluted nature of my career. This bifurcated – and weird combo – of being a cartoonist, and then a political staffer, and then a cartoonist, etc. But I’ve come to accept needing a day job some of the time. I interned for Barney when I was very young. Later, I was working as an art director at a magazine and when it folded, and he said, come be my staff counsel. That lasted four or five years, during which I started publishing Ethan Green, which got picked up by St. Martin’s Press while I continued to work during the day for Barney. In 2000 I thought, “fuck it, I should try to make a living full-time drawing”. The only place I knew that could happen was in Los Angeles, working in animation. I did some production work, and then, some storyboarding at Disney. Which was a scary, like being chained to an oar on one of those galley ships in ancient Greece. [laughs] Then the Great Recession hit and my animation gigs dried up, and I was out of work. Barney said, “come back to Washington and be the Financial Services Committee press secretary.” So all told, about ten years, but not in one fell swoop. That had its advantages in telling this story because I was present on and off. Of the people who make up his political family, I’m sort of a prodigal son.

So beyond making Ethan Green, you were doing various art jobs over the years.

Yeah, right out of college, I landed a job as editorial cartoonist for the daily Concord Monitor in New Hampshire’s little state capitol. I’m still proud of having gotten that job. It was a small newspaper that did daily battle up there with the Manchester Union-Leader. Everything was great except my personal life was nonexistent. New Hampshire wasn’t a comfortable place – for me anyway – to be young and gay at a time when the mushroom cloud of HIV was looming up over everything. There was a lot of hysteria and fear of gay men up there. And I wanted to meet someone. So I moved down to Boston, basically so that I could find a boyfriend. Now I’m like, who gives a damn about finding a boyfriend! You had this great gig, and they can be more trouble than they’re worth! Get a dog! [laughs] Anyway, I moved to Boston and I got a job as assistant art director at a magazine.

Those periods of working for him being separated by a number of years – and eventful years, not just in terms of Congress but public life – were very different and I would imagine, gave you a different perspective.

It gave me a good, often front row seat. Two years before I left to go to Los Angeles, I was sitting in my office working in Barney’s Massachusetts district office. I would draw Ethan at lunch because I had a nice, enclosed office and it wasn’t the taxpayers dime because for lunch, I was off the clock. So anyway, I was in my office and I had been in there for several hours, first working and then switching gears and trying to finish my comic strip. In this district office, the only good camera shot for a live TV crew was if you put up a backdrop against the outside of my office door. So I was in there working and I heard commotion, but it was a congressional office. There’s always commotion. I kept trying to come out, and getting the door forcefully shut in my face. Barney was on the other side of the door, on camera with one of Boston’s network affiliates. When I was finally freed, I discovered that the live shot I’d almost interrupted was to get Barney’s take on the breaking news about the president and this intern named Monica Lewinsky. Who of course nobody had ever heard of that morning.

He’s an interesting figure in terms of the work he did, and a lot of people know him for that, but for many people and some of the media, he was a colorful character.

Definitely a colorful character. But also, a guy who combined a really sharp wit, in service of strategic thinking about public policy. One of my favorite quips of his is one that I heard long before I met him. I was in the kitchen of a house I shared with roommates during my junior or senior year of college. Somebody on the radio was saying in this thick accent, “these right wingers must believe that life begins at conception and ends at birth, because they nevah support social spending after that”. My roommates were standing there – unlike me, they were from Boston, so they’d been hearing Barney on TV for years – and they explained who he was when I asked.

Whether people like politics or not, we live in a political system. The great laws of the land – the 15th Amendment, the New Deal, the Voting Rights Act – all that was legislation. You need somebody that knows how to draft, and pass bills. And Barney knows how to do that. But unlike a lot of people with legislative skills, he also could communicate in a way that galvanized people. Buy yeah, there’s no question he’s very colorful. It’s important to remember that he came up in the seventies and eighties, this era of focus-grouped politicians. Barney was the antithesis of a blow-dried, glad-handing, people-pleasing, talking out of eight sides of their mouth politician. That made him interesting for the media, and interesting for the voters.

You really get into this in the book, that he is a policy wonk above all else. He’s one of these people who doesn’t just write bills, but he actually reads bills.

It’s not particularly interesting to your average Joe – and I get that. He might not be wearing a cape and saving old ladies from I dunno, Spider-man’s nemesis, or whatever, but those intellectual qualities can be pretty heroic when it means that you’ve managed to win rent subsidies or healthcare, or better VA benefits for people. That’s what drove me to want to tell this story. And yeah, he’s absolutely unusual. You think the Representative from Q-Anon, Marjorie Taylor Green or spineless Kevin McCarthy, or that truly creepy Matt Gaetz are spending their Friday afternoons reading bills? I promise you they aren’t. And that’s a shame. It’s essentially a parliamentary system, but if nobody is practicing that, the wheels of society start to spin off. God knows we’re seeing plenty of that.

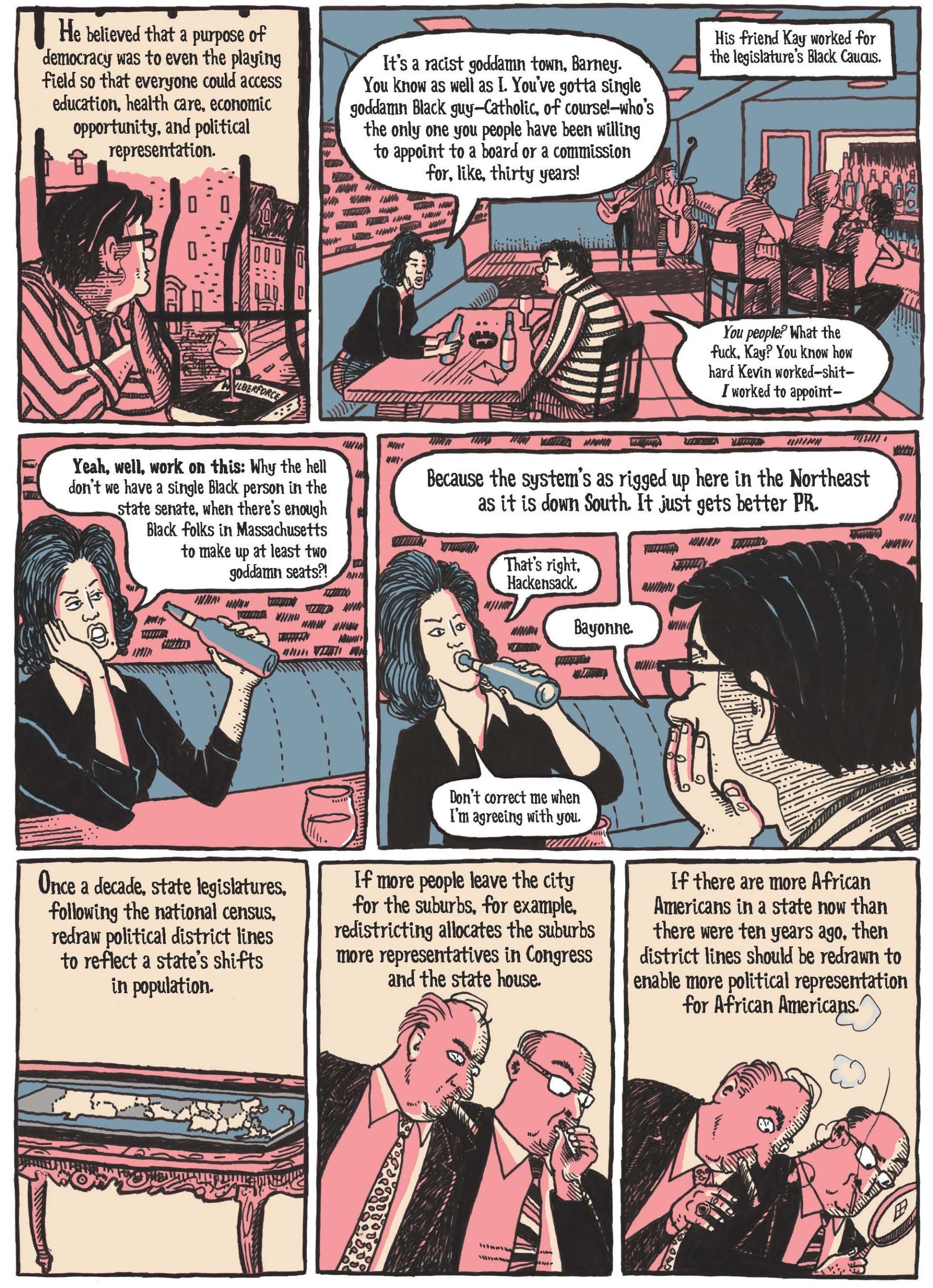

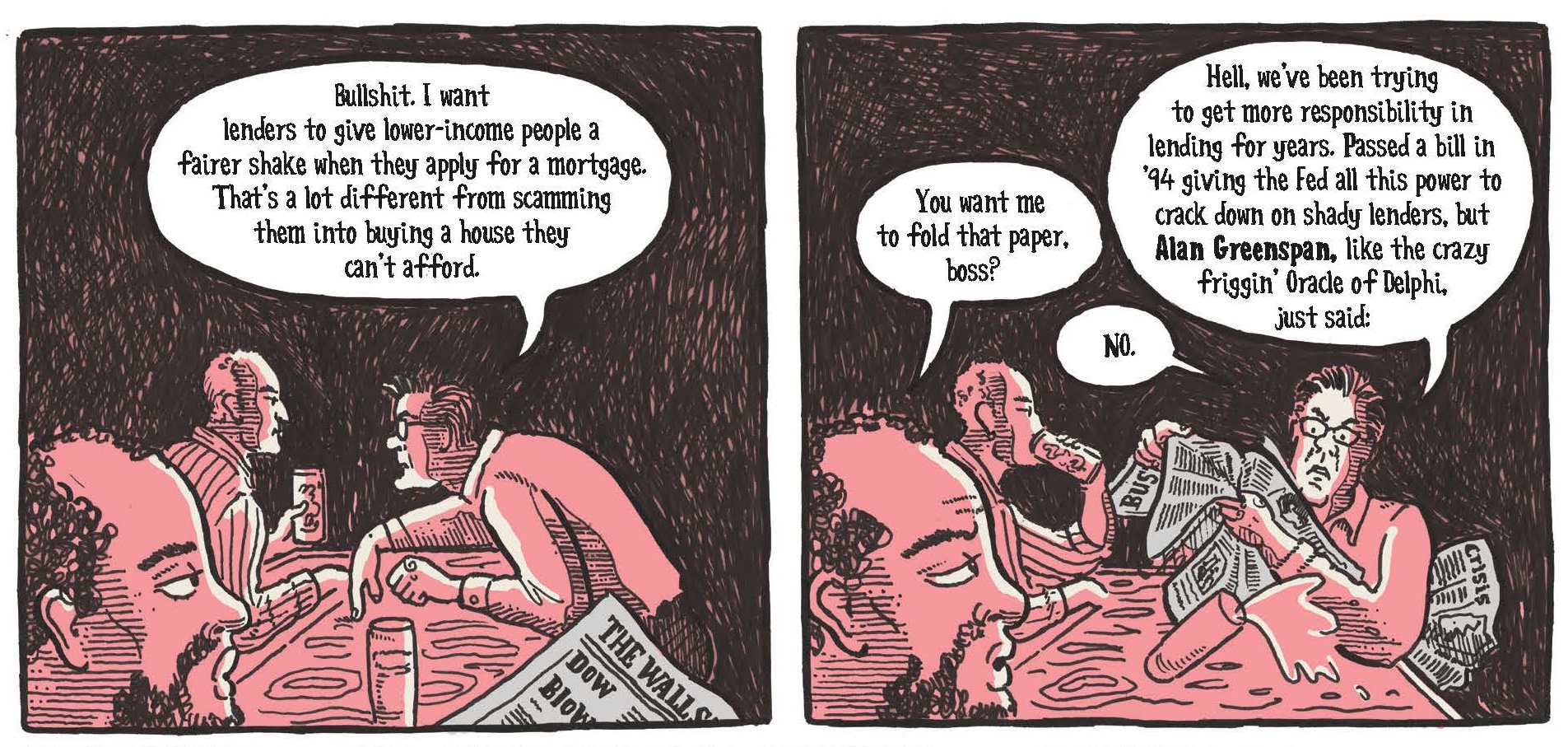

In this book you found ways to dramatize writing bills, reading and researching bills, which are not necessarily visual and dramatic, but you find a way to make it very compelling.

That’s good to hear. I looked at it as sort of political equivalent of the kind of police procedurals you see on TV. They’re interesting in the first five minutes because, someone finds a body, but after you find the body in the freezer in those first five minutes, then for the next 55 minutes or whatever, it’s all procedure. The dramatist’s job is to make that interesting. That’s what I wanted to do in Smahtguy.

From the start of his career he’s been interested in housing and how does one use government to serve people and help people.

I agree with you, but to me, his career’s more dramatic than that. I see it as really about the ongoing fight against American Reaction. Given the political climate over the past five years maybe I should drop the pretense and just call it fascism. There has been a strain of hyperactive conservatism in this country since its founding. The difference between the left and the right I think, is that the right has more often been willing to marry legitimate conservative politics with the threat – or the actuality – of widespread violence. Think of the segregationists. Think of Timothy McVeigh. Sure, the Weather Underground pulled violent stunts from the left. But they were hapless. I saw this book as a dramatization of the last forty years of the fight against American fascism through the prism of one important combatant’s career. So I think it’s a little more dramatic than just dramatizing his very real concerns about affordable housing or even Wall Street reform. Barney was a significant combatant in the fight over the last forty years from basically the Civil Rights era through the Great Recession.

I think that’s a great way to put it. Many people will see him and this book as centering queer culture, but his work is about so many things – schools and housing and race and class and economics. It’s about fighting the hypocrisy of people who attack “welfare queens” while handing out huge contracts to cronies that do nothing.

Absolutely. And it’s nice that you remember that incident! You’re right. I’m not really talking about welfare, I’m talking about hypocrisy on a societal level. Confronting that is the form that this man’s work took. It’s probably less interesting visually – than a graphic novel about, say, the Stonewall Riots, or the civil rights movement , but narratively, well, I wouldn’t have written a book about Barney’s work if I didn’t find it inspiring.

Trying to pass legislation and what it takes to do that and spending years doing this work. It’s very unglamorous, unexciting work but that is the kind of work that progress is built on.

Well, I think heroism is exciting. In this case, it’s quiet heroism. I understand what you’re saying, but in my heart of hearts, it’s exciting.

What was the process of researching and writing this? I assume you sat down with him and other people.

I did a lot of research. I spent a lot of time going over parts of his life that I was less included in. I know many of the main players, his contemporaries, adversaries, allies, opponents, family members, partners, through the years. All that was an advantage and a disadvantage. An advantage because I’m conversant in a lot of these things that if you weren’t conversant in, I think you’d have more trouble in making them compelling. The familiarity allowed me to feel comfortable telling certain parts in shorthand where somebody who was a little less confident might feel the need to explain, I dunno, the Taft-Hartley act in detail. My attitude towards readers-to be, was, “don’t worry if you’re less familiar with the ins and outs of politics, just come along with me. I’ll try to make it worth your while…and funny”. After a year and a half of researching, interviewing, reading a ton, I was like a clam that snapped shut, and didn’t want to talk to him or any of the people who populate this book, because at some point you do have to actually start writing. I have always needed a tight script before I pick up a pen. Then, I’m drawing it and I can’t really have any more input. I would never have finished it, while drawing, I was getting calls or texts from people with knowledge of his career offering new information… “Hey, are you including the time when he stepped on Andrei Sakharov’s mother’s foot?, or whatever” [laughs] That’s the sort of thing I don’t want to hear after I’ve begun drawing. So I shut out the world, consider the storytelling – with the exception of the dialogue – locked and just…draw.

Going back to Ethan Green and earlier in your career, did you always write a tight script before you started drawing?

With Ethan I wrote everything out first. When I was working in animation a teacher told me something that’s stuck with me; be open to letting your characters act when you start drawing them. Just like actors, they will take the material and make it alive. I agree with that when it comes to dialogue. I need to start with the writing – what I really consider the narration – but then I feel more comfortable letting myself have some fun with the character’s acting. I draw the little picture of I don’t know, The Hat Sisters, or Tip O'Neil, or anyone really, Julia Child, expecting the drawing to look a certain way. But the drawing of Julia, let’s say, doesn’t. She looks this other way. Like she’s saying this, instead of the that I expected her to say. To me that’s the joy of cartooning. I know not everyone agrees. There are many people nowadays who write a book and then somebody else draws it. I’m a pretty old school cartooning about this. There are some brilliant books out there with that setup, but to me there’s always something a little off, in the connection between the narrative and the dialogue and the drawings. The best way I can put it is that it’s like watching a dubbed movie. It doesn’t make it not enjoyable, but when there’s that bifurcation of labor, one person writing, another person drawing, things always seem a little off to me.

Making Ethan, you were making a strip and with that format you had to be very strict in terms of what you were doing.

The deadlines were pretty relentless. A lot of the time I was juggling lots of different things – like being a staff attorney in a congressional office – when I was trying to get that strip out. Drawing a weekly comic strip you have to be very disciplined. And of course I would run opposite the genius of Alison Bechdel’s Dykes to Watch Out For. She always made it seem so positively easy. I’m sure she’d roll her eyes to hear me say that – especially having read her great book The Secret to Superhuman Strength, which details her struggles with making the Dykes to Watch Out For deadlines – but that’s how it seemed. She never had any spelling mistakes or ink smudges! [laughs]

I’ve always thought of Ethan as part of the generation of strips that followed Dykes To Watch Out For and Wendel in a lot of ways.

I wouldn’t disagree with that. Though I wasn’t trying to emulate Wendel or Dykes when I started. I was looking at certain straight comic strips: Sylvia, the feminist strip by Nicole Hollander and Cathy, by Cathy Guisewite. Not in terms of tone, but subject matter. Dating. Men as creeps. And I wanted to write about a guy who wasn’t a Tom of Finland muscle queen, and wasn’t Uncle Arthur on Bewitched, vamping around, either. I wanted Ethan to be funny and full of pratfalls and idiocies, but he wasn’t outrageous physically. It was about an average looking guy and his dating trials and tribulations, and that was really taken from Cathy.

And I looked to Mimi Pond. She had this brilliant back page in the Village Voice called Mimi Pond’s Secrets from the Powder Room. She published a book of them with the same great title. It was about women out at night clubs or parties or restaurants in New York. And they would excuse themselves to go to the bathroom together so that they could talk about what unfathomable jerks they were out with that night. I was like, “that’s what I want to talk about!” Wendel was beautifully drawn, had a lovely sweetness and integrity. But that wasn’t really where I was coming from. I wanted Ethan readers to feel like someone was whispering something edgy and funny and a little surprising in their ear. Something that was often about putting up with the bullshit of dating. During Ethan Green’s fifteen years I wrote about a lot of different things, but that was the initial idea.

I actually have Cathy in my notes. Because I think we talk about Ethan in terms of those two strips because it’s queer, but Ethan has a lot more in common with a comic like Cathy and it feels a piece with a lot of nineties sitcoms and comedians in terms of tone. Not snarky, not campy, kind of edgy.

Agreed! It wasn’t camp. Donelan was camp. I don’t have a problem with camp. There were definitely campy elements to Ethan – his best friends the Hat Sisters were drag queens, but you’re right in saying camp wasn’t what was informing me. TV sitcoms were much more where my head was. Mary Tyler Moore, Seinfeld. Serialized newspaper fiction, like Armistead Maupin’s Tales of the City, and Bob Green’s Bagtime in The Chicago Tribune. In terms of cartooning, I always felt most at home at home with the people drawing for alt weeklies. Subversive anti-establishment kind of stick-it-to-‘em kind of cartooning. Mimi Pond. Anybody in the Village Voice. Feiffer. Edward Sorel. Stan Mack, Lynda J. Barry, Ben Katchor, all those Pushpin cartoonists from back in the day; R.O. Blechman. The great Mad Magazine cartoonists Drucker and Sergio Arigonès, and Don Martin. And I admired a lot of the fearless and funny editorial cartoonists from when I was growing up. Pat Oliphant, Tony Auth, I wanted to be like them.

I first read you in an alt weekly and I’m curious about the breakdown of LGBTQ newspapers versus alt weeklies that carried Ethan.

Maybe ten percent of my papers were alt weeklies, but I was proud to be included in them. I was in alt-weeklies in college towns like Northampton MA, and Burlington Vermont. And these papers didn’t mind controversy: the great Baltimore City Paper ran a strip that many of the LGBTQ publications shied away from: Ethan is in bed with his partner Doug and you see them having sex, but it’s not at all sexy. Because Ethan isn’t thinking about sex, he’s thinking about an appointment they have later in the day with a real estate broker. I guess the joke was, a lot of the time, sex isn’t sexy at all. The DC Blade, which was an LGBTQ paper, insisted I tweak the images to cover the guys up. The paper wanted acceptance and approval. But most cartoonists aren’t really looking for acceptance and approval. Even one that’s moonlighting on Capitol Hill! [laughs]

You have a line in the book: “He made himself a deal: he’d have a political life, not a personal one.” That’s very much the story of a generation. And before obviously. But that was the deal they had to make with themselves.

Barney’s part of a generation that began its political life in the 1960s and 1970s. Stonewall had happened, but the thousands and thousands of gay people who worked in politics were still pretty closeted back then. I mean, in the mid ‘60s, LBJ’s top aide, Walter Jenkins was run out of the White House because they caught him one too many times in a tea room. Those were defining moments for people of Barney’s generation. You just couldn’t do politics and be an out gay man or woman. It took 20 years after Stonewall for liberation to reach political life. When Barney started, it just wasn’t an option to be out. He happened to be serving in office when suddenly the world changed – with help from Harvey Milk, and others – and he sensed that possibly the world actually was ready for this. People think of Barney as a big Northeast liberal, but his district wasn’t Boston or Cambridge. Southeast Massachusetts is more like Upstate New York. Or central Pennsylvania in its political orientation. So when he came out, it was a very uncertain bet that his voters would send him back to Congress. Turns out, he bet right.

I’m from Connecticut.

So you know. People think, oh, polite little New England. I’ve spent time in places in spots in Connecticut that are as culturally conservative as places in the Midwest. Certainly, as much as places in upstate New York where I spend a lot of time. The difference is only that you drive 25 miles and you’ve left that, where in other places you have to drive 400 miles.

In certain regards this book feels like story of generation who grew up in a different world and helped to change it in significant ways.

Definitely. In the last pages of the book, I say that for somebody who’s personal life held such little promise, it turned out that his timing for coming out and leading his life as an out public figure was pretty perfect. And in doing so, you think of the floodgates of people in public life now who are LGBTQ. It’s a big, big difference from thirty years ago or more. When I think of all the good Barney’s done, it’s not because he was the first this or that. The fact is, everybody was coming out then. He had the bravery to join them. I’m not saying he paved the way, although I suppose just by virtue of his visibility, he impacted people.

Beyond politics, he was someone who spent a long time focused on work and I think a lot of us can relate to consoling ourselves with work, but also what it means to get a little older and work doesn’t quite mean what it used to.

You’re left with some emptiness. I keep saying that he’s heroic, but in my mind he’s really more like an anti-hero. I say this in the book. He wasn’t pretty. He didn’t die young. His personality wasn’t always pleasing. His mixed up troubled personal life was a real important part of his story. And at the center of that story is a scandal that nearly tanked his whole political life. It was a pretty rough thing to have to go through.

Barney Frank was one of Tip O’Neill’s proteges, and when Frank comes out to him, you have a line where O’Neil said, I thought you could have been the first Jewish Speaker of the House, and coming out of the closet ended that possibility.

He would have made a good Speaker. I mean we have probably the most dynamic Speaker of the House in history right now, though it doesn’t feel like a time to be proud of. I think people in Barney’s orbit were surprised that Tip O’Neill remained pretty stalwart through Barney’s coming out. Tip was somebody who Bay Staters loved – and miss – and his reaction was only that because he was in the business of counting votes. After Barney told him about being gay, Speaker O’Neill was like, “well, we’re not going to have the votes for that.” [laughs] But when Barney told him, Tip wasn’t standing on a chair shrieking like an elephant looking at a mouse, either. His reaction was just, “all right, we need to recalculate a little bit”.

It’s true today in many fields, if you’re going to come out and be true to yourself, there still is a glass ceiling. It’s unclear where, but it’s there.

You said it better than I could have. You’re absolutely right. Clearly though, in this day and age it’s better than it was.

Significantly better. And very different from when he started and when he grew up. He might not have gone as far, but he was happier, and he was good with that.

Absolutely. I wanted to tell a human story. I didn’t want the book to be “and then he did this legislative thing and then he did that political thing.” That’s not very interesting. And not very instructive to anybody. He’s a person who overcame some real pain to find something whole. I don’t kid myself thinking there’s lots of fourteen-year-olds dying to read about housing policy in cartoon form, but I do like to think that if they stick with it, they’ll see that, and that might be useful.

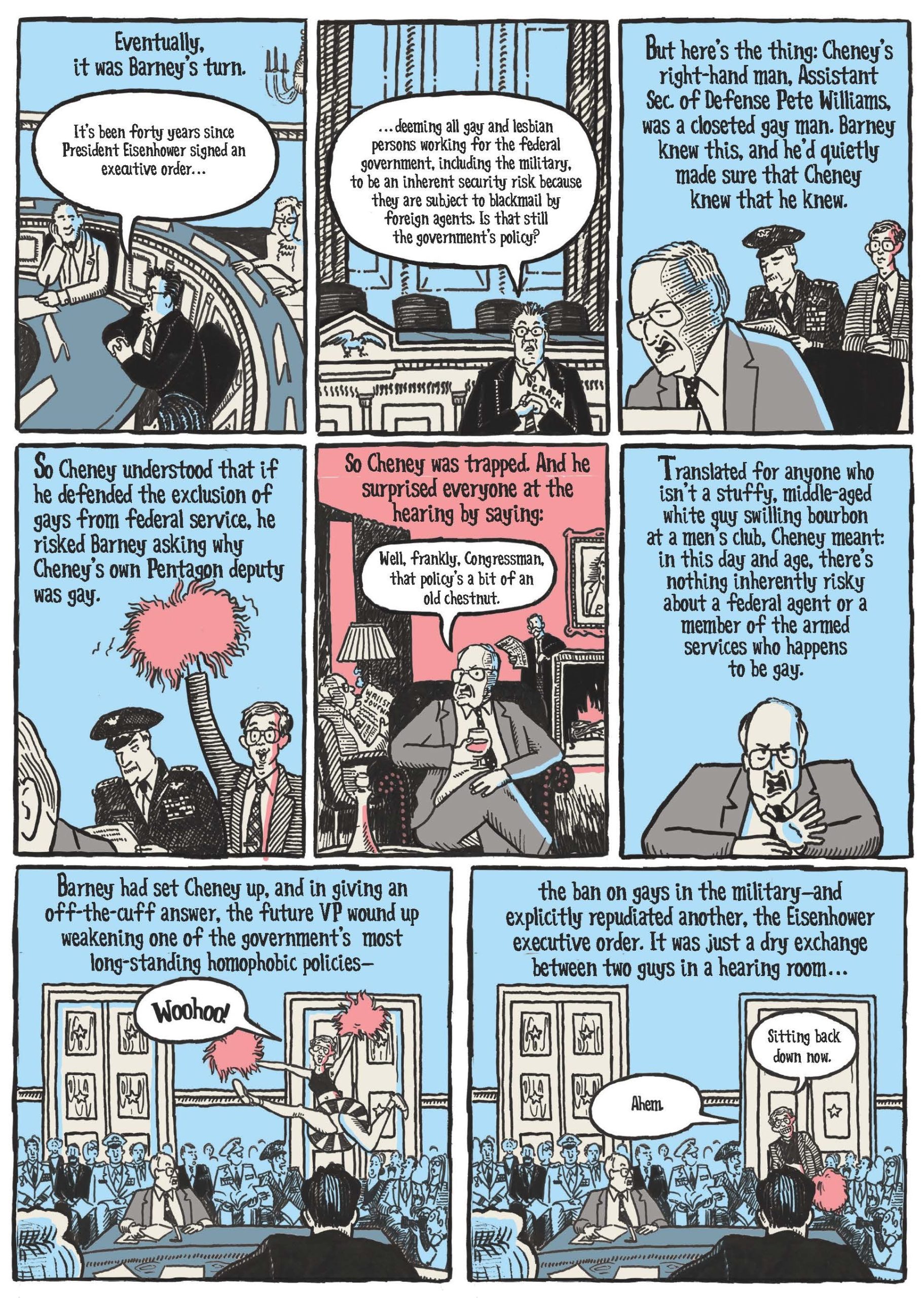

There’s one scene I wanted to talk about near end, which I think is instructive in how you approach the book. The 1991 hearing with then-Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney. You make it clear that Frank asks a very long wonky question, but there was something very important in that question and the answer. That way you were trying to say, here’s something that seems dull and ordinary, but it was a big deal. And this is part of what you find so compelling about Frank and a lot of what he’s done.

What goes through my head goes back to our earlier conversation about procedurals. In a mystery show, there’s a point at which the person is putting these facts together to come up with a conclusion that’s much more interesting than the assortment of facts. In that case, Dick Cheney’s Chief of Staff happened to be gay. Cheney knew it and Barney knew Cheney knew it – but what it all means is, bam! Again, a political procedural. A lot of times politics is a blur for people. In these hearings the debate gets drowned out in specifics and people don’t really understand what’s going on. But sometimes something up there crystalizes, and people go, “Oh, that’s what this means. It means something real. It means something to me.” It resonates. I’ve always thought those moments are pretty dramatic. Like the Watergate hearings or the Anita Hill hearing. They didn’t start out that way. Watergate was a baffling set of facts. It didn’t start out as “what did the President know and when did he know it?” It started out, why were they taping doors in the Watergate hotel? Who was doing this? Cubans? The CIA? Writing about congressional politics like a police procedural or legal procedural, what you’re hoping for is that people see the bigger picture, but you can’t tell the story without getting in the weeds a little bit. I didn’t want to stay in the weeds too long, but the entire writing of Smahtguy was about balancing big picture against weeds.

I think the scene stood out because it shows a lot of what he did throughout his career – and what politicians are capable of doing. To see these connections and take these small moments, one bill, one hearing, and affect change.

What you’re talking about in this case is terrific hypocrisy. Hypocrisy that’s been going on in this country for its entire modern life. President Eisenhower admitted that there was no problem with gay people, but maybe the Russians would blackmail them. Well, the only reason blackmail would work is because being gay was held against them! There was an admission all along that it was just because we don’t like these people and we want to treat them badly. I didn’t want to be didactic, so I didn’t say it in the book, but it colored my thinking: there’s this old phrase from the Hippy era, and on into the seventies – if it feels good, do it. The slogan referred to sex, but I feel like we live in a country where so many people – mostly conservative, but people on the left, too –absorbed the if it feels good, do it ethos, and applied it generally to how they interact with the world around them. It’s become permission to behave terribly. Whether it’s yelling at a bird watcher in Central Park, or screaming at a flight attendant, or invading the fucking Capitol in a loincloth. That’s how they feel at the moment! “It feels good, so I’m just doing it!”

I’m a patriotic guy, but I also understand there’s always been a cruel and bullying aspect to America’s personality. Maybe it’s because of capitalism. This Darwinian struggle that we encourage. These are the things that were coloring my thinking while I was trying to tell Barney’s story because he fought against them. His whole life was animated by fighting against that sort of bullying, that sort of “I don’t give a damn if this makes my neighbor unhappy, or worse, because it’s my right to do what I want”. Because he was big and burly and could be bullying himself, he felt like it was his responsibility to stand up for folks who weren’t as strong as he was. That’s his real nature.

You get at the hypocrisy. Like how Dennis Hastert and Newt Gingrich denounced Barney Frank and voted to censure him. They also have no shame so they don’t see this as a problem, but those two men did so much worse. And Hastert makes Gingrich look like a saint.

Hastert is so pathetic. When I wrote about him, I was like, “this is mean, Eric”. But I also thought, “he asked for it!” Not that Denny Hastert gives a damn what I write on the thousandth panel of a dense graphic novel.

I actually thought you were very polite in describing him. More than he deserved!

Well good! [laughs]. I mean, I called him a “pervy ex-wrestling coach”, so, y’know, not all that polite.

But just as Barney Frank wasn’t a hypocrite, attacking gays and then going to gay clubs, he wasn’t pretending to be something he wasn’t. He wasn’t this polished New England WASP.

Or this big city Irish pol. Barney’s first boss Kevin White was this great scion of a Irish-Catholic political machine. If you consider Barney’s start in politics in Boston, you have to think: what the hell was this guy even doing there? [laughs] and the reason he became this 24 year old Jewish chief of staff to the Mayor of Boston – which in this day and age I don’t think people would look twice at, but anybody helping run City Hall in Boston back in 1968 who wasn’t Irish and hadn’t had a grandpa and a great-grandpa on the public payroll since the 1880s, was a big surprise.

He was unusual because didn’t have the pedigree or personal connections. He didn’t come up through politics the normal way.

The only thing he had was the ability to work hard. The funny thing is, that’s what the rest of them didn’t want to do! They wanted to practice politics; they did not want to practice governance. That’s always been Barney’s silver bullet. He actually reads the bill. He reads the policy memo. He writes the policy memo. He thinks about these things. How you make complicated public policy about transportation and housing and infrastructure work. A lot of people in politics are there for the politics. Barney never liked the politics. He liked the policy. He thought campaigning was a grind, but for most of them campaigning is what they like to do. They don’t want to read an 800 page bill, but they don’t mind getting up at 6 am and standing at the train station and glad handing. That made him pretty unusual figure in the political world.

I thought of the press conference he held after his scandal broke and he stood there and answered questions until the reporters ran out of things to ask him. I don’t know that I’ve ever seen that.

You wonder why more of them don’t do it? He thought that “the only way my voters are going to even consider allowing me to continue this work is if I’m honest with them.” He once said to me that the first thing politicians do when they get in trouble is call their lawyers and the second thing that happens is that they get terrible advice. The lawyers say, “clam up”, and that’s not the way politics work. By the time he was done answering all the embarrassing questions, the voters sorta shrugged, and said “well, that’s embarrassing. Many people’s personal lives are complicated and messy.” And they gave him a pass because he didn’t look like he was hiding anything.

This is your first graphic novel and after drawing and cartooning for decades, what has the form and the process been like for you?

It’s my first graphic novel, though The Mostly Unfabulous Social Life of Ethan Green ran for fifteen years and was compiled into five books (four from St. Martin’s Press and a final omnibus from Northwest Press) and those compilations read like graphic novels, in that Ethan was always a serialized storyline.

Smahtguy is essentially a biography, told – I hope – novelistically. There’s a first act, a second act, a third act, but I couldn’t entirely get away from the linear quality of a person’s life, as the book’s framework. I picked incidents that I thought created a narrative arc. I thought it was important to the narrative to say that this guy was an outsider from the get go, a working class boy from New Jersey. He wasn’t from Belmont, or Beacon Hill or Marblehead like so many of the rest of the people who went to Harvard when he did. His life continued to be an expression of outsider status until the very end of his career. Even when he was a Committee Chairman in Congress, when he was in those late-night meetings during the financial crisis exercising a lot of political authority, that doesn’t mean he was one of them. These people are all sitting there at four o’clock in the morning in their coats and ties, looking like they’re ready for a funeral or a wedding or a church service, and Barney looks like he just got out of bed. He just put a jacket over a t-shirt and his hair is messed up. The rest of them just got out of bed too, but it wouldn’t do, in DC, not to look the part. No matter how urgent. He was always different.

You follow his life in a very linear way, and the ending has something of a novelistic quality to it.

That’s nice to hear. Obviously his life’s not over, but I like the place where I ended it. I was thinking about what we talked about earlier, about timing, and how somehow this was just pitch perfect. And nothing about Barney – except his political acumen – is pitch perfect. So that was interesting.

What’s behind the title, Smahtguy?

I wanted something that conveyed both his irreverence and my own. I wanted to telegraph something intimate and funny. Not intoning and pompous. “The Fight for American Liberalism” or “American Pugilist” got rejected. Titles are important to me. With Ethan I wanted people to understand, before reading a single line, that this was not about fabulousness. This was not about Fire Island. Even if he went to Fire Island in an episode! This wasn’t Queer Eye for the Straight Guy. It wasn’t about this notion of gay men knowing the right sets of forks and having the right haircut and the right biceps. I wanted that clear before you even read it. I hope Smahtguy makes clear that he was smart, and held in a certain amount of esteem and awe by his constituents, but also there was a level of familiarity. A level of irreverence. I hoped that that title conveyed all that. Bostonians aren’t impressed in general. Even when they’re admitting, okay, you are a smahtguy. You did all these good things. That was the thought behind it. Irreverence.

I know there’s a beat of confusion when people read the title for the first time. But what I am finding and I hope I continue to find is that after a beat, they get it and then they smile. I looked at a lot of biographies and so many are titled boringly. The worst thing is when they just title it the person’s name. Or I’m looking at one on my shelf – Disraeli: Modern Thinker. Benjamin Disraeli was a great British Prime Minister – and he was weird! He was writing sexual fiction and he was going off to meet with Queen Victoria and tease her a little too much. “Modern Thinker?” That doesn’t tell you anything.

Smahtguy works because as you say it’s a compliment, but also with a little mockery. It’s very specific.

Right. Again, with The Mostly Unfabulous Social Life of Ethan Green, I felt I had a title that belonged over each episode. On the other hand I was often undermined by some gay publication or other that would write a story about Ethan and they would call it “The Mostly Fabulous Social Life of Ethan Green”, which was a dagger to my heart. There’s nothing fabulous about the guy. That was the point.

If you had called it Ethan Green, that’s not memorable.

There were some great titles of kids books when I was a kid. Like there was a book, From the Mixed Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler about kids who sneak into the Metropolitan Museum of Art and live there. I can’t remember the reason, but I remember looking at that title and being like, what? It interested me. It provoked me. Even though I didn’t know why. Those are the sort of titles that I like.

Talking about storytelling, the cover. Frank is front and center and in background many different kinds of protestors. Half of whom readers will agree with and half readers will loathe. And places him in that context of protest.

I’m glad you think so. The title was a big ongoing discussion between me, my agent, my editor, and the publisher. Then it came to me after eight months. I was sitting right where I am now and I thought, his constituents think he’s smart – no wait, they think he’s “smaht.” The cover on the other hand, sort of took care of itself. I drew it for the book proposal, and we never abandoned it. There were some tweaks and the designers of the book did some work, but it was the same basic image from the very beginning.

In a way, not revisiting the cover during the three or four years it took to create the book, is a hangover from my time as a Disney story artist: At the end of every long day at the studio in Burbank – if you weren’t pulverized from drawing storyboards and exhausted and scared that they were going to fire you (as I usually was) – six o’clock would come and you could go take free classes downstairs. They had some of the great visual artists in the world and they would teach you amazing things, for free. It was part of your compensation. I wasn’t lucky enough to go to art school. I should have, but I was lucky enough to get a second shot at art training there. Anyway, sometimes in animation, the looseness of your first drawing, before you consciously try to incorporate all your boss’s (and The Mouse has a lot of bosses) notes, is the best. For Smahtguy, the cover was the first thing I drew. My editor kept going back to it, while I protested that the image was just to get Holt or whatever publisher nibbled, to understand who I was writing about! It’s a complicated drawing. Sure, there’s some humor in it. But it’s busy. It’s not slick. That’s what my work is like. And they – my editor, my agent, the designers at Metropolitan Holt – all said, “Y’know, let’s stick with it”.

There’s a lot of storytelling in that image.

For better or for worse, that’s the kind of cartoonist that I am. The kind that bends your ear about something. Even if it’s bending your ear visually! [laughs]. People are going to either indulge you or they won’t. But I guess I’d better do what comes naturally, than try and fail to become, I dunno, some genius like Chris Ware at this stage. I did learn some nice artistic skills that I really value, like I was saying, but I’m not a designer first.

You’re an illustrator first. It sounds like Disney was a mixed bag in many ways, but you got something out of it.

I value having gotten in the door, and what I learned there. What happens when you get out to L.A., you get on a trajectory and it becomes hard to change. I probably should have been the guy getting coffee for the writers and working my way up at Family Guy. Or some opinionated TV show. That would be more my speed. Instead, I wound up at Disney drawing Tinkerbell’s sisters, or coloring storyboard drawings on the Bambi sequel. Never really was my thing. But I feel like it’s the cartoonist equivalent of having served in the army.

After everyone finishes their first graphic novel, people either loved the experience and want to make more or they say, never again.

I’ll definitely draw more books. Drawing’s my life. I mean I don’t mind yoga, but drawing is my practice. And my business. I’m going to draw anyway. So why not draw a book! [laughs] I have two different ideas that I’m on the verge of pitching. One is ready and the other needs another three or four months of writing. They’re both political. Ethan’s sensibility was political even though it wasn’t about politics.

I would have assumed that after Ethan you would make a graphic novel. You were clearly interested in a longer narrative.

I appreciate that. God knows I tried. The timing was lousy because it came up against the recession. First I was working at Disney and I was literally afraid to do anything other than practice drawing the way they wanted me to draw. Then the recession happened. Then it took me a while to get something right. But now I feel like I’ve been training and I’m very primed to do more.