The following article was originally written as a chapter in author Brian Doherty's forthcoming book Dirty Pictures: How an Underground Network of Nerds, Feminists, Misfits, Geniuses, Bikers, Potheads, Printers, Intellectuals, and Art School Rebels Revolutionized Art and Invented Comix (Abrams, 2022), but was cut for space. It is presented here in a slightly altered form, as a standalone reflection on the underground generation of American cartoonists and their often-admiring, sometimes-fraught relationship with predecessors from the straight world.

-The Editors

* * *

Fredric Wertham and his deeply-educated liberal humanitarian concern over how young kids’ minds were warped dangerously toward delinquent and criminal behavior by gross, poorly done, violent and hideous cheap pop entertainment was somewhere in underground cartoonists’ ancestry, the anti-inspiration, the foil. And whoever the people were responsible for the notorious “8-page Bibles” or Tijuana Bibles, or just plain “fuckbooks,” illegal porn pamphlets of cartoon characters and film celebrities gleefully fucking were grandfathers at least, or so Art Spiegelman was certain; “The Tijuana Bibles weren’t a direct inspiration for most of us; they were a precondition. That is, the comics that galvanized my generation—the early Mad, the horror and science-fiction comics of the fifties—were mostly done by guys who had been in their turn warped by those little books.”1 (The publishers of underground comix would have swooned with joy to master the clandestine, criminal, still-occluded means by which these things got to barber shops, barracks and junior high yards across the nation in the Depression era and beyond).

But the true and undeniable Father Figure could be none other than Harvey Kurtzman, the Brooklyn-born child of Ukrainian immigrants who grew up making sense of the world through reading newspaper comic strips, then made sense of it by cartooning himself—like father, like children.

“If you put these artists up, they’ll take full advantage of you and be lazy bums.”

Kurtzman was always a soft touch for a nice little hand-scrawled note if younger artists mailed him the fanzines or comix he inspired, even if he always had to decline doing work for them—he was a pro with a family and had to work for pro rates. Even past his nurturing of so many of them in the pages of Help! in the first half of the 1960s, even as the actual underground comix phenomenon began to explode, he tried to get the undergrounders—mostly Robert Crumb—higher profile professional work, perhaps not quite understanding a divide in generations or just spirit between himself—Kurtzman, wanting the secure, cushy, high-paying pro gig—and Crumb, driven by a desire to draw his cartoons and not be hassled.

Though Kurtzman tried to dote on his artistic children in his way, like even the best fathers he didn’t always understand them the way they wanted to be understood; once he started doing his more LSD-inspired style, Crumb remembers sadly, Kurtzman thought he was making a big mistake and didn’t get the new thing. He thought Crumb’s late ‘60s work was “vastly inferior to my earlier stuff.... he just didn’t get it.”2

While wrangling the job, Kurtzman hung out with his boys on the west coast and, while ostensibly researching a Little Annie Fanny for Playboy where she gets into hippie free love, went around with Crumb and Spain Rodriguez to some commune scenes, one of them so grotty and scary it truly unnerved Kurtzman, including when he thought he saw an adult fondling a young girl.3 On a less horrifying note, he participated in a weird Victor Moscoso project called “Science Fiction Comics” which involved filming a gang of artists—including Kurtzman and most of the Zap crew—drawing a poster, so that what resulted, as Moscoso explained it, “was a live action movie with some animation. It was a jam of us doing a poster to advertise the movie of us doing the poster. Cool, huh? It’s like a circle. The poster advertises the movie; the movie is us doing the poster to advertise the movie. Harvey Kurtzman flew out from New York and I met him for the first time.”4

At a 1971 convention in New York, Kurtzman gave a strong public passing of the torch, telling a crowd “I don’t read newspaper comics anymore because they are totally dead but underground comix are really exciting. And I tend to think they are exciting because they are related to what’s happening today. They’re new, and fresh, and they’re a frontier. And a frontier is always exciting.”5

Kurtzman was himself—as much of a creative inspiration as he’d been to young Crumb—a hideous Bad Example, inspiring Crumb to be as professionally unlike Kurtzman, trapped doing Hefneresque work to Hugh Hefner’s niggling demands, as possible. “Kurtzman was caught, trapped. I saw him break down and weep once,” Crumb wrote, “describing the way Hefner was always blue penciling his roughs for Little Annie Fanny. It was terrible to witness.”6

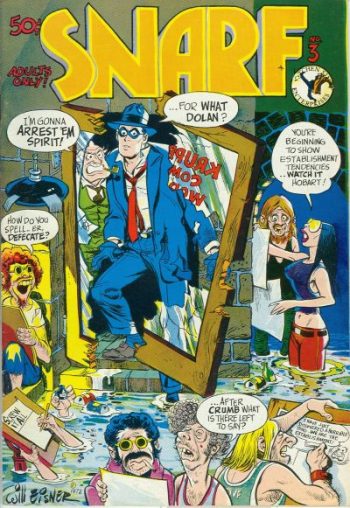

Kurtzman, of course, was a natural friend of the undergrounds, and gave cartoonist and publisher Denis Kitchen both a cover for his humor anthology Snarf and an all-Kurtzman underground comic book, Kurtzman Komix, in 1976. Terre Richards of Wimmen’s Comix and Manhunt! remembers how much Kurtzman encouraged and enjoyed the company of the underground women at San Diego Comic-Cons. “He was a great supporter of the undergrounds, he thought what we were doing was revolutionary, and the fact we were all young pretty women didn’t hurt.” She recalls Melinda Gebbie jumping into the pool at the convention hotel with all her clothes on screaming “Harvey Kurtzman! Harvey Kurtzman! Come out and play!” after he’d departed after an afternoon of gabbing at the bar with the underground women. Richards saw him coming out of his hotel room door on the balcony overlooking the pool “and his fuming wife behind him.”7

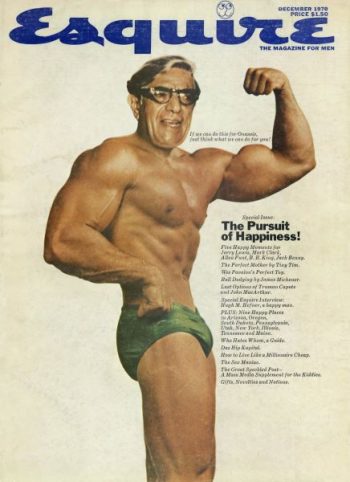

Their closeness to Kurtzman did give the underground boys some access to America’s most respectable naughtiness, Playboy. Hefner was as big a Kurtzman nut as any of the undergrounders, even if that might have manifested in a sadistic need to prove his own mettle by conquering and taming the father figure, and had even funded Kurtzman’s first post-Mad project, a slick humor magazine called Trump that only lasted a couple of issues in 1957. Kurtzman, after the failures of Humbug and Help!, was reliant on Hefner’s patronage to keep his family alive, via the sexpot/satire strip Little Annie Fanny produced by him and his old Mad partner Will Elder.

Kurtzman did value the conventional respect, the expense accounts, the access to the dudeish decadence, of being part of the team in this fabulously successful cultural explosion of Playboy, in the heyday of its first couple of decades especially.

Kurtzman had some business to conduct with Hefner and asked Kitchen to drive him into Chicago and promised him a five-minute tour of the Playboy Mansion for his trouble.

The impecunious Kitchen had a loose muffler on his ‘61 Chevy that fell to the ground as he was pulling into the Mansion driveway. “Two guards rushed out right away, and recognized Harvey. Harvey said, ‘This is my friend’ so they said, ‘Sir, we’ll park your car,’” Kitchen recalled.

Sammy Davis Jr. answers the door, in purple short-shorts. Harvey escorts Kitchen through famous paintings, suits of armor, rooms of arcade games, Playmates everywhere, down to the underground home of the see-through pool. Every stop, drinks are offered. It has already gone long past the five minutes Kitchen was promised. But no one was pushing him out.

Then they’re in the living room and Harvey tells him, hey, Hef gets first-run movies, stay for a movie. Harvey guides him to a specific seat on a couch; the seating is arranged to face one wall. The retractable curtain comes down and Kitchen realizes Kurtzman maneuvered him to sit on Hef’s couch, so Kitchen finds himself with Miss April between him and Hefner.

They watch a Paul Newman film about racing. Afterward, thinking surely he must be going, Kurtzman introduces his “friend the underground cartoonist” to Hefner, who politely invites Kitchen to stay for a meal. Kitchen recalls the movie wall somehow opening up into an insanely sumptuous dining room, with food “created not just by a chef—by an artist” and he’s stacking his plate with “food I wouldn’t even dream of from my flat in Milwaukee.”

Kurtzman, delighting in shepherding his poor friend into this taste of the wealthy and decadent life, and in prankishly keeping him unsteady on his feet, tricks Kitchen into sitting in what turns out to be Hef’s place at the head of the table, which the pajama-clad host-with-the-most kindly allows Kitchen to keep. Any friend of the great Harvey Kurtzman....

Hefner knew the undergrounds. He told Kitchen of his failure to lure Crumb to selling out to the Playboy empire. Shel Silverstein’s there, of course, and tells Hef that it would be a mitzvah to the cause of cartooning for him to just take a little, a tiny taste, of his vast wealth and just fund some free apartment/commune for good young cartoonists to work, free of worries of a roof over their head.

“Hefner’s puffing on his pipe slowly, thinking. And Harvey—my so-called friend!—says, ‘No, it’s a terrible idea.’ Hef says, ‘Why, why is that Harvey?’ Harvey says ‘If you put these artists up, they’ll take full advantage of you and be lazy bums. They won’t do anything. There’ll be nothing but trouble out of it. Trust me. I’ve known a lot of artists in my life.’”

Even the end of dinner isn’t the end of Kitchen’s five-minute tour of the Playboy Mansion. No clocks were visible anywhere in the Mansion but he’s told it’s late, stay the night. “The waiters are bringing Hefner a new cold Pepsi after every few sips, so it’s never less than very cold. And one of the waitstaff comes and whispers to Hefner, and Hefner turns to me and says ‘Your automobile is fixed.’”

Even in the morning, Kurtzman tells Kitchen, hey, before you leave, order breakfast. Order anything you want. “I suggest ham and eggs, something like that. And Harvey says, ‘You’re in the Playboy Mansion. Order anything you want. You want a lobster for breakfast? Ask for it!’”

Kitchen drove back alone to Milwaukee, that night, and sat in his tub and stared at the flaking paint on his bathroom ceiling and remembered the past 24 hours when he was not broke in his cheap flat.8

On another occasion, Robert Crumb's Cheap Suit Serenaders were touring through Wisconsin and crashing, as they did, with Kitchen. The tour coincided with Kitchen having brought Kurtzman in to lecture about comics again. As cartoonist and Serenader Robert Armstrong remembered, they were part of the caravan taking Kurtzman back to Kitchen's after the event and the impecunious young undergrounders’ crummy cars nearly led to the freezing death of their Master as they ended up having to push over a hill the pickup truck with the spinning-out bald tires that was dragging behind it the Karmann Ghia with the broken accelerator cable containing the founder of modern American satire so they could at least get him into the shelter of Kitchen’s farmhouse. When they got there, the heat wasn’t working.9 (In other circumstances in later times, but perhaps with this trauma having stained his brainstem, Kurtzman told Kitchen, “If you were rich, you’d be perfect.”10)

Crumb, Jay Lynch and Skip Williamson also got to party at the Chicago Mansion thanks to Harvey’s ginger appreciation of their adoration for him. What transpired was a perfect encapsulation of the relationship between Kurtzman, a family man needing to make a living, impressed even against his more sharp satiric judgement by the trappings of worldly and cultural triumph that Hefner and the Mansion represented, and his symbolic bratty kids. They needed well-paying cartooning work too, and Hefner was a fan, scholar and patron of the cartooning arts.

Williamson was feeling like a punk, and loudly and drunkenly declared his intention to—why not?—shit in the grotto pool. “Kurtzman was trying to get some money from Hef at the time, for creating Annie [Fanny],” Williamson remembered. “So Jay [Lynch] told Kurtzman about what he thought I was going to do, and Kurtzman thought this would diminish his ability to get a raise, if I did that. I’d completely forgotten that I’d said I’d do that, when I stripped down naked and jumped into the pool. The security came, closed down the pool, and hustled me out. I didn’t know why I was being kicked out. I got angry because I thought that it was because I was naked in the pool. I said, ‘what’s the matter? Haven’t you ever had naked people in the pool before?’ so I got dressed, kicked a suit of armor in the shins, and stormed out, before Hef even showed up.”11

Crumb found the whole experience at the Mansion dispiriting and a blot on his memory of his hero and mentor Kurtzman. “There’s nothing to do around there. The only thing to read was copies of Playboy which he had placed on all the end tables and coffee tables. There was TV; you could watch TV. But God, it was really creepy. Like a Holiday Inn or something. It was really weird.... cheap shit paneling on the walls and real thick carpets.”

Jane Lynch and Crumb’s then-girlfriend Kathy Goodell tried to ask the bunnies how they could bear those absurd outfits. “The bunny just said that for four hundred bucks a week you’d do it too.” Crumb recalls they never saw Hefner because he was holed up with a friend playing backgammon the whole time. “Kurtzman was like sweating; he didn’t want anybody to disturb Mr. Hefner. He was like worried that somebody, me or Jay Lynch or Skip Williamson, would upset Mr. Hefner.”12

Hardly a Kurtzman acolyte from his Mad days could look at Little Annie Fanny with anything but disquiet. Paul Buhle, the Students for a Democratic Society academic who spearheaded Radical America Komiks, had the nerve to confront Kurtzman about it in a letter, telling him he idolized him, he was the most important figure in his teen life, how could he take part in something any intelligent “supporter of women’s liberation like myself would despise and reject as degraded?” As Buhle remembered, Kurtzman kindly answered, being “incredibly candid,” reminding Buhle that Playboy was the only magazine he had been involved with that hadn’t failed or let him down, and, after all, mortgages and health benefits were something even America’s greatest satirical mind needed.13

Hefner wasn’t the only Chicago culture icon the underground boys would beard in his den. All the youngsters had an awed, weird affection for the grotesquely delineated law and order strip Dick Tracy, whose master Chester Gould oversaw the city from an aerie atop the Chicago Tribune tower. Crumb and Lynch visited, and Crumb was dazzled by “this real grizzled character.... the only guy left of the old school who really works at it. He’s amazing.”14 Lynch recalls the cigar-smoking old cartoonist actually saying nice things about the art they brought to show him, then basically morphing into Dick Tracy before their eyes, “looking down from his tower and he saw these criminal types like thirty stories below walking around, and he said, ‘If any young punk ever tried any funny business with me on the street I’d break his arm and set him on fire.’” And when Crumb tried some modern bleeding-heart liberal socio-economic foofaraw on Gould, Gould responded sharply: “‘Buddy, if you can’t tell the good guys from the bad guys, then you’re one of the bad guys!’” Lynch recalled this fateful meeting of old-school strip and newfangled comix mentality happening portentously enough on the day J. Edgar Hoover died.15

“He opened it up and there was a page where a pirate has cut off the tip of somebody’s dick...”

Kitchen was always an ecumenical lover of great comics, past present and future, and was thrilled he was the guy to bring down to the underground Will Eisner of the legendarily graphically innovative and literarily sharp The Spirit, a unique series of 7-page comic book-style short stories that appeared in a newspaper supplement around the country in the 1940s and early ‘50s.

Kitchen met Eisner in 1971 at a New York comic book convention run by Phil Seuling, later the main innovator in the “direct market” distribution method for mainstream comics that emulated the underground innovation of nonreturnable sales, breaking out of the standard (often shady) world of big time east coast periodical distribution.

“Eisner reached out through an intermediary and I met him in a hotel room. I had no idea why he wanted to meet me, but turned out he had heard about underground comix and Will, as I learned later, was an insatiably curious guy, especially when it came to new comics business models. He just peppered me with questions and then he confessed that he had never really seen any underground comix. And he was curious to see some, and so I said, well, sure, you know, Phil Seuling at that time had at least two full tables covered with every underground that was available.

“My intention was to curate it and to pick two or three examples to introduce him. He was older and I didn’t want to pick the most X-rated ones, but before I could do that, he impulsively just reached down and he picked up what I believe was Zap #2.

“He opened it up and there was a page where a pirate has cut off the tip of somebody’s dick [and eats it]. And he says the tip tastes best or something like that. Will looks at that and I thought his eyes are gonna leave his head and he put it down I started to try to explain that well.... he already knew they were uncensored, but I said, ‘You know, you picked up kind of an extreme version of what the genre offers.’

“And Will said, ‘Yes, I guess I did.’ I could tell he was, although liberal, upset by it.” Kitchen recalls Art Spiegelman coming upon them and beginning to defend S. Clay Wilson, the cartoonist of the gruesome pirate tale. “Suddenly Will was feeling a little bit badgered and felt he had to extricate himself and I thought, well, I'll never see him again. But he had handed me his business card during our meeting in the room. So when I got back to Wisconsin, I made a point of writing to him and telling him that I thought he should see other examples. And I included six or eight things I'd published. And that changed everything because he then was very positive and the rest is history.”16

Eisner did not fully embrace the underground’s live and let live freedom, though. In 1975 he wrote a cease-and-desist letter to a comix title, New Paltz Comix, that parodied The Spirit’s style, telling them “I’m sure that your obvious copy of the logo style and the use of the Spirit was not intended to hurt me, but it has.... and if it continues it will certainly do me considerable harm.... I therefore have the moral obligation to police the usage... I ask that you immediately suspend the obvious imitation of the Spirit” while wrapping up with the mollifying “I am always interested in helping underground fanzines, and I doubt that you will find me uncooperative where such permissions do not conflict with other commitments.”17

Those first two Kitchen Sink Spirit comix sold so well Eisner was poached by James Warren for a Spirit comic magazine to go alongside Warren’s Creepy, Eerie and Vampirella. But Kitchen poached him back in 1978, and spearheaded as editor and publisher Eisner’s rise in the 1980s to grand old man, inspired by Crumb, of the serious graphic novel with strong memoirish tinges.

“...For I conceive it in my mind and put it down on paper with a lot of sweat and love and shit like that...”

Eisner wasn’t the only old-school genius Kitchen tried to co-opt. Thrilled by the dual coups of Eisner and then Kurtzman covers for Snarf, Kitchen got in protracted and ultimately fruitless negotiations with Li'l Abner creator Al Capp. “I offered him the chance to spit in the eyes of hippies and he’s seriously considering it,” Kitchen said at the time. It would have been a great publicity stunt for both sides, Kitchen believed.18 But the underground money was not enough to encourage the grumpy Capp to put ink to board.

Wally Wood told Kitchen at a summer 1972 convention in New York that he also wanted to jump on board the underground train. At the time, Kitchen recalled, the always-struggling, always-seeking master, adored by nearly all undergrounders, “said he was sick of the old publishing houses and was ashamed of the hack stuff he had been turning out in recent years. He seemed to be really excited about the opportunity to do whatever he wanted and keep the rights and the originals... some of the other ‘old timers’ were interested too. The word ‘underground’ used to turn them off, but now they see it in terms of the new economics involved. It’s really gratifying to be able to offer these guys a clean deal.”19

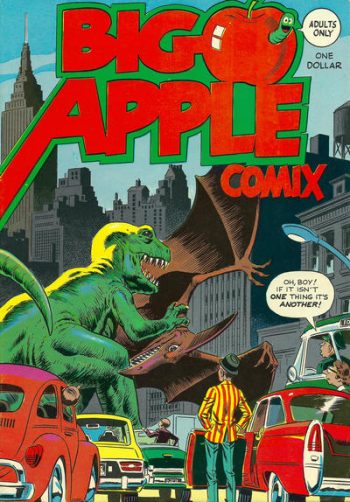

Wood had published his own proto-underground, though it overlapped the normal world of commercial superhero and fantasy artists more significantly than it did underground folk. It was called witzend, launched in 1966 with his own art, some by science fiction illustrator Jack Gaughan, and contributions from old EC hand and later adventure strip and comic book artist Al Williamson. Issue two from 1967 featured Spiegelman along with post-Kurtzman Mad mainstay Don Martin, plus Kurtzman himself and Spider-Man co-creator Steve Ditko, among others. Ditko debuted in witzend #3 his most vivid exploration of his dedication to Ayn Rand’s Objectivism, Mr. A., who metes out pure reasoned justice to wrongdoers with no emotion-laden respect or consideration, which their evil actions prove they don’t deserve. Ditko was given more pages to work out his harsh-but-just political thoughts in later witzends. More consistently underground folk also appeared in witzend, such as Grass Green (one of the very few black creators in the undergrounds, who arose from the comic/superhero fandom world, both serious and parody), Vaughn Bodē, and Roger Brand (who started as Wood’s assistant and went on to edit undergrounds such as Real Pulp and Tales of Sex and Death). witzend was trying to stake out neither an “underground” nor overground space, mostly being “the unofficial house organ of Wallace Wood studios”20 and pals. Wood also in the late 1960s, for Paul Krassner’s The Realist magazine, drew a highly bootlegged image that had a very underground comix flavor to many, in that it—shades of the Air Pirates, though Wood was first and got away with it—portrayed a bevy of Disney trademarks, er, characters having an orgy.

As underground comix publisher Ron Turner of Last Gasp once said discussing especially the horror/sci-fi underground artists circling around Skull and Slow Death, “If we had been a cult, we would have had a shrine to Wally Wood.”21 He represented something magic not only in his impeccably captivating figures and inkwork, his frankly just-plain-wicked-cool worlds brought to vivid, thick, textured life, but in the scandalous, searching figure he cut, the living embodiment of the glories and pains of trying to be a great artist in the constraints of commercial comics culture that he kept trying to escape but never quite successfully did; the kind of tragically romantic figure that compelled both admiration and fear. If you were a New York cartoonist you wanted a chance to hang out at his studio, even if you might get anti-mentoring wisdom, as recalled by Joe Schenkman.

The young underground artist already thought the superhero spy comic T.H.U.N.D.E.R. Agents that Wood was spearheading in the mid-‘60s was beneath his genius, and it hurt to watch him go through those motions for even the bad money of third-rate publisher Tower. Old Mad guys like Wood “were to be worshipped, so when they hacked, you know, it’s... it’s just kind of sad. You notice they are only doing a fraction of what they can do, and why is that?”22 The “why” is a complicated stew of commercial constraints, disappointed ambition, and the old “inner demons.”

It’s amazing considered how detailedly and rigorously gorgeous Wood’s work was at its best how deeply cynical he could be about the whole endeavor, at times advising starry-eyed youngsters to never draw what you can swipe and never swipe what you can trace and never trace what you can cut and paste; that since getting started with your drawing tasks is the hardest part, once you get started just do whatever you must to keep going for days; and, at his most bilious, that he would sooner cut off his hand than relive his life as revered comic book artist Wallace Wood. That’s where being the absolute master of ink in the service of American comic books got you.

Trina Robbins in her New York days also got to honor her childhood admiration for his work by spending time with the man. “Art Spiegelman introduced me to Wood and we became very good friends. But he was very troubled and unhappy. He was a little cynical—a little? Very cynical—and liked to play with guns. That grated on me, him and his guns... and of course he destroyed his liver, but that was much later. When women’s lib became a big thing he said some really stupid things. He said to me, ‘These women’s libbers are just ugly women who can’t get men.’ He’s saying this to me and I happened to be really a babe. I was totally, really a babe and he’s saying this to me!”23

Spiegelman remembered that “as I became more involved with the underground newspaper scene and the stuff that was happening in the East Village, Wood was intrigued by that world and wanted to go slumming with me, and get laid in it, know more about it.” Spiegelman enjoyed his company but felt the 20-year age gap a bit off-putting. Toward the end of their active relationship, Wood was reduced to “some kind of residency hotel with drunks all over the place and half-swigged coffee or liquor around. My second visit was much more like out of a film noir Venetian-blinded world... at the time I met him Wood had lost his original inspiration and was doing a lot of hack work.”25

Spiegelman still speaks weightily of one day in the 1970s getting a letter from Wood of such depth, such deeply personal pain, in Spiegelman’s estimation beyond what would be expected given the nature of their relationship, intimate beyond expectation, seeking advice he wouldn’t know how to give, that a baffled Spiegelman never answered it.26 In 1981, scheduled to go on dialysis the next day, Wood shot and killed himself, never having contributed new work to Kitchen.

“I told the kids that the bad guys have a little good in them, and the good guys have a lot of bad in them and that you just couldn’t depend on anything much.”

Another unifying childhood love for the underground generation was who they only knew as “The Good Duck Artist,” forced to write and draw as if he were Walt Disney, whom they later learned was Carl Barks. When he emerged into the fandom light in the 1970s and started doing paintings of some of his iconic characters and images (he invented Scrooge McDuck) and met the younger generation, Barks was surprisingly understanding and appreciative of them in all their filthy-mindedness. And he could see the imprints of his fingers in their minds: “I noticed that Crumb's underlying message,” he said, “is that nothing is important enough to be taken seriously. This was a message I often sneaked into my duck stories.”27

Barks saw his influence on underground attitudes with his duck stories a little more deeply, and darkly. “I told the kids that the bad guys have a little good in them, and the good guys have a lot of bad in them and that you just couldn’t depend on anything much. I just didn’t disguise anything or make things rosy.”28

Other attempts to find common ground with pre-underground creators that the new generation respected came to not much. Jerry Rubin thought old-guard intellectual cartoonist Jules Feiffer, in Chicago to cover the riotous Democratic Convention in 1968 for the Village Voice, might enjoy meeting a representative of the younger generation of what passed for comics intellectuals, and tried to introduce him to his pal Skip Williamson. Williamson, alas, reported that Feiffer was “disdainful and aloof” and considered the undergrounders “a smear on the good name of cartoonist.”29

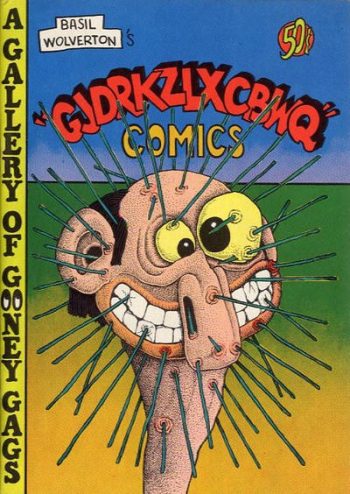

Bray thinks Wolverton saw the wrong things first, like Eisner did, and that if Bray had gotten to him first he “could have turned him on to the undergrounds via Bijou” since Wolverton “does still have a remarkable love for the absurd.” But Bray knew that Wolverton literally threw away a copy of Robert Williams’ Coochy Cooty Men’s Comics since, being very religious, anything porny or showing a dick would revolt him. Bray delighted in relating to his comix pals Wolverton’s still well-honed sense of whimsy, with lines such as “If I stop breathing and fall down, just let me lay there. That’ll be a lesson to me” and insisting he had retired from cartooning, and when asked what he did now, “pointed out the motel window to a van marked ‘world’s greatest motorcycle jumper.’”30

Right toward the end of Wolverton’s life, Denis Kitchen was working on an aboveground distributed comix magazine for Stan Lee and Marvel, Comix Book. Kitchen wanted some Wolverton pages, but “was afraid if I even described it as underground, he wouldn't do it. But because it was for Marvel and Stan Lee was paying the bills, that’s why I think he did it.” (Kitchen is also very glad he had the urge to commission a portrait from Wolverton at the time, one of his very last drawings.)31

There were other old guard reactions surprising from either direction; that Bill Mauldin, G.I. cartoonist extraordinaire, would dig S. Clay Wilson, and that rugged war cartoonist Russ Heath would be so offended by getting free copies of Bijou Funnies in the mail as an offering from fan Jay Lynch that he threatened to have Lynch arrested if he saw another one of his damn comix—neither seemed reasonable.32 But underground comix, in all their wonder and squalor, were great at eliciting passionate and unlikely responses, from readers and the law.

* * *

- Art Spiegelman, “Those Dirty Little Comics,” in Bob Adelman, ed., Tijuana Bibles: Art and Wit in America’s Forbidden Funnies, 1930s-1950s (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1997), 5.

- Robert Crumb, The R. Crumb Coffee Table Art Book (Boston: Little, Brown, 1997), 207.

- Bill Schelly, Harvey Kurtzman: The Man who Created Mad and Revolutionized Humor in America (Seattle: Fantagraphics Books, 2015), 481-483.

- Gary Groth, “Victor Moscoso Interview,” The Comics Journal #246, September 2002, 81.

- Schelly, Harvey Kurtzman, 484.

- Robert Crumb and Peter Poplaski, The R. Crumb Handbook (London: MQ Publications, 2005), 256.

- Terre Richards, author interview, February 3, 2020.

- Quotes and details on Kitchen’s Playboy Mansion experience with Kurtzman from Denis Kitchen, author phone interview, January 28, 2021.

- Robert Armstrong, author phone interview, May 11, 2020.

- Kitchen, author phone interview, January 28, 2021.

- Skip Williamson, “The Daily Crosshatch Interview: Skip Williamson (March 1, 2007),” conducted by Brian Heater, Spontaneous Combustion (self-published Kindle book, 2011).

- Al Davoren, “What I Think of All the Foolish Nonsense I've Been Involved In,” in D.K. Holm, ed. R. Crumb: Conversations (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2004), 63-64.

- Paul Buhle, author phone interview, May 20, 2020.

- Thomas Maremaa, “Who Is This Crumb?” in Holm, ed. R. Crumb: Conversations, 32.

- “Jay Lynch Interview Part One,” Cascade Comix Monthly #6, August 1978, 4.

- Quotes and details on Kitchen introducing Will Eisner to underground comix, Kitchen, author phone interview, January 28, 2021.

- Comix World #38, December 1975, 2.

- Letter from Denis Kitchen to Joel Beck, February 17, 1976, Kitchen Sink Press Records, Columbia University Rare Book and Manuscripts Library, Box 1, “Beck, Joel.”

- Letter from Denis Kitchen to Robert Crumb, July 19, 1972, Kitchen Sink Press Records, Columbia University Rare Book and Manuscripts Library, Box 2, “Crumb, Robert.”

- Bill Mason, “Any Idea in Any Form,” in witzend (Seattle: Fantagraphics Books, 2014), vii.

- Ron Turner, “Last Gasp,” in Mark Burstein, ed., Dave Sheridan: Life with Dealer McDope, the Leather Nun, and the Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers (Seattle: Fantagraphics Books, 2018), 14.

- Joe Schenkman, author phone interview, March 7, 2021.

- Trina Robbins, author interview, December 17, 2019.

- Wally Wood, “My Word,” Big Apple Comix, September 1975, [unpaginated, but 13 including cover].

- Gary Groth, “Art Spiegelman Interview,” The Comics Journal #180, September 1995, 85.

- Art Spiegelman, author Zoom interview, December 29, 2020.

- Michael Barrier, “The Filming of Fritz the Cat Part I,” Funnyworld #14, Spring 1972, accessed on the web.

- Quoted in Crumb and Poplaski, The R. Crumb Handbook, 290.

- Williamson, Spontaneous Combustion.

- Letter from Glenn Bray to Jay Lynch, December 6, 1970, Jay Lynch Collection and Papers, Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum, Ohio State University, Box JL2/Folder 2 “Correspondence July-December 1970.”

- Kitchen, author phone interview, January 28, 2021.

- On Mauldin digging Wilson, see letter from Jay Lynch to Glenn Bray, August 16 [no year, but context makes it almost certainly 1971]. On Heath threatening Lynch, see letter from Jay Lynch to Glenn Bray [undated, though context makes it very likely the year was 1971]. Both letters in Gift of Glenn Bray, Jay Lynch Collection and Papers, Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum, Ohio State University.