Igor Tuveri, aka Igort, is a key figure in the contemporary Italian comics scene. Well, actually, he has been a key figure for the last 30 years. He is the founder of both Coconino Press, publisher of the some of the most relevant Italian comic artists, and, more recently, Oblomov Edizioni, with which he continued in the same direction. Since 2018, he has also served as chief editor of the venerable Italian comics magazine linus. As an author, Igort produced several graphic novels; 5 is the perfect number (2002) is probably his most widely-translated work, which also inspired a live-action movie directed by Igort himself in 2019.

While Igort has ventured into many genres during his long career, his work with the nonfiction comics Ukrainian Notebook ("Quaderni ucraini", 2010) and Russian Notebook ("Quaderni russi", 2011)–published in English by Simon & Schuster's Gallery 13 label in 2016 as one volume, under the title The Ukrainian and Russian Notebooks: Life and Death Under Soviet Rule–is particularly relevant today. Those two books explore Eastern Europe's recent history, approaching graphic journalism from a wider historical and humanistic perspective; it can give relevant keys of interpretation for what has been going on in Ukraine since the end of February.

While Igort has ventured into many genres during his long career, his work with the nonfiction comics Ukrainian Notebook ("Quaderni ucraini", 2010) and Russian Notebook ("Quaderni russi", 2011)–published in English by Simon & Schuster's Gallery 13 label in 2016 as one volume, under the title The Ukrainian and Russian Notebooks: Life and Death Under Soviet Rule–is particularly relevant today. Those two books explore Eastern Europe's recent history, approaching graphic journalism from a wider historical and humanistic perspective; it can give relevant keys of interpretation for what has been going on in Ukraine since the end of February.

A few days after Russian troops entered Ukraine on February 24th, Igort came back to the topic using a different language, this time with no images. For over 60 days on his Facebook page, he wrote daily entries called Telephone Chronicles ("Cronache dal telefono"). In just a few lines, he was telling the stories of tens of Ukrainian citizens dealing with the conflict and the Russian siege. These stories were raw, unfiltered, coming straight from friends, relatives, and from the people he’d met during the time spent in Ukraine years ago as he worked on Ukrainian Notebook. On May 10th, after 65 days, he put an end to these chronicles. The war is still far from over, as I’m writing this now.

Reading Igort’s chronicles was a genuine experience during those first days of war - so much different than reading newspapers reports or listening to war correspondents (and I can tell you that because I’ve fed a lot from the news, almost bulimically). I was curious to know what kind of work Igort was doing with his Telephone Chronicles; if this was going to become a new book. So I recently visited him in his house in Bologna, located in one of the main streets of the city center, not far from the two leaning towers.

In past years Igort has also lived in Paris, in his native Sardinia, and in Ukraine, but he has always had a special relationship with the city of Bologna. "I came back to Bologna a couple of years ago. I love this city." It is in this city that he started the Valvoline group in the '80s, along with Daniele Brolli, Giorgio Carpinteri, Marcello Jori, Jerry Kramsky and Lorenzo Mattotti (and Charles Burns, when he was living in Italy). It is in Bologna that he started Coconino Press, and it is where he is now running Oblomov Edizioni.

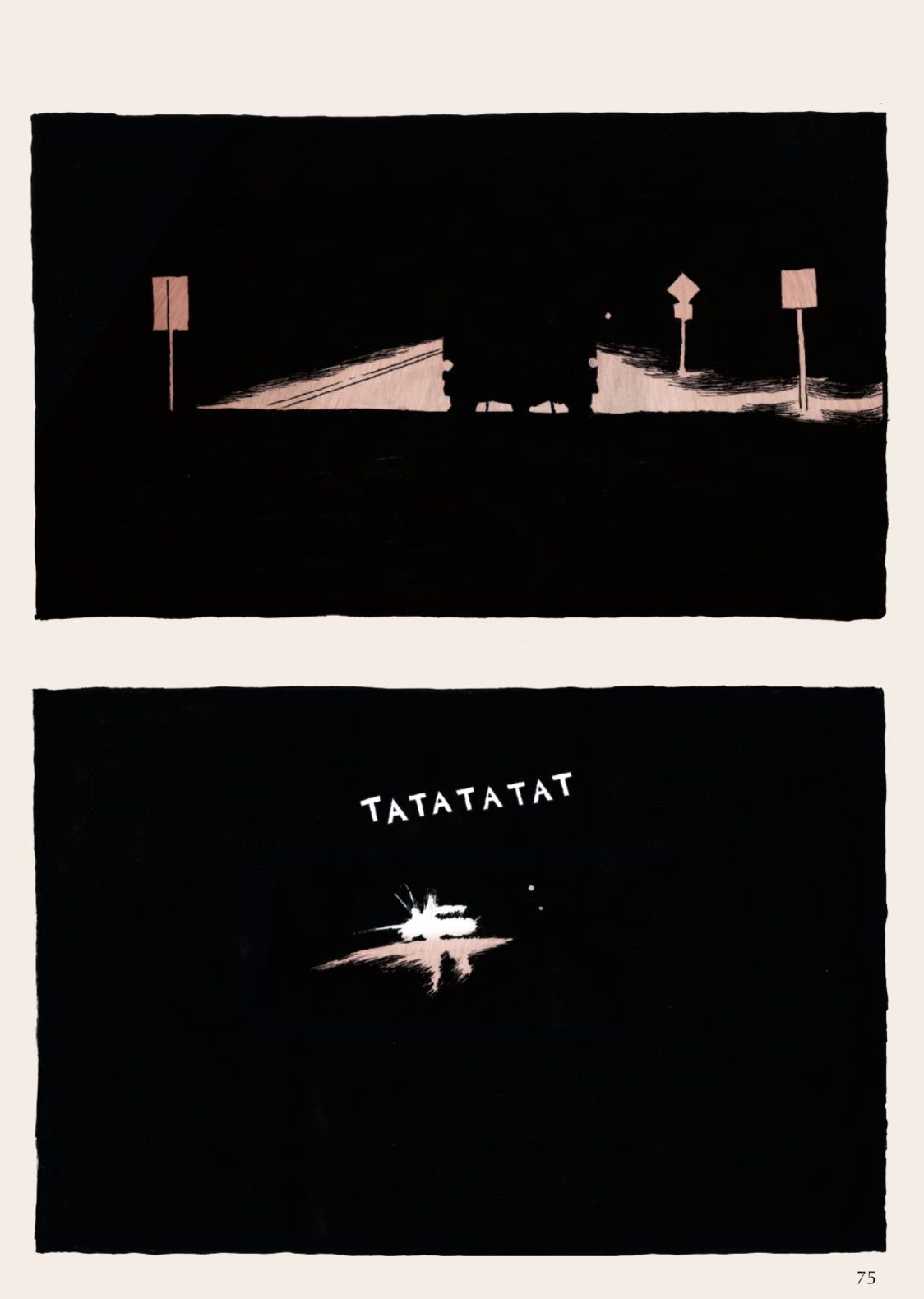

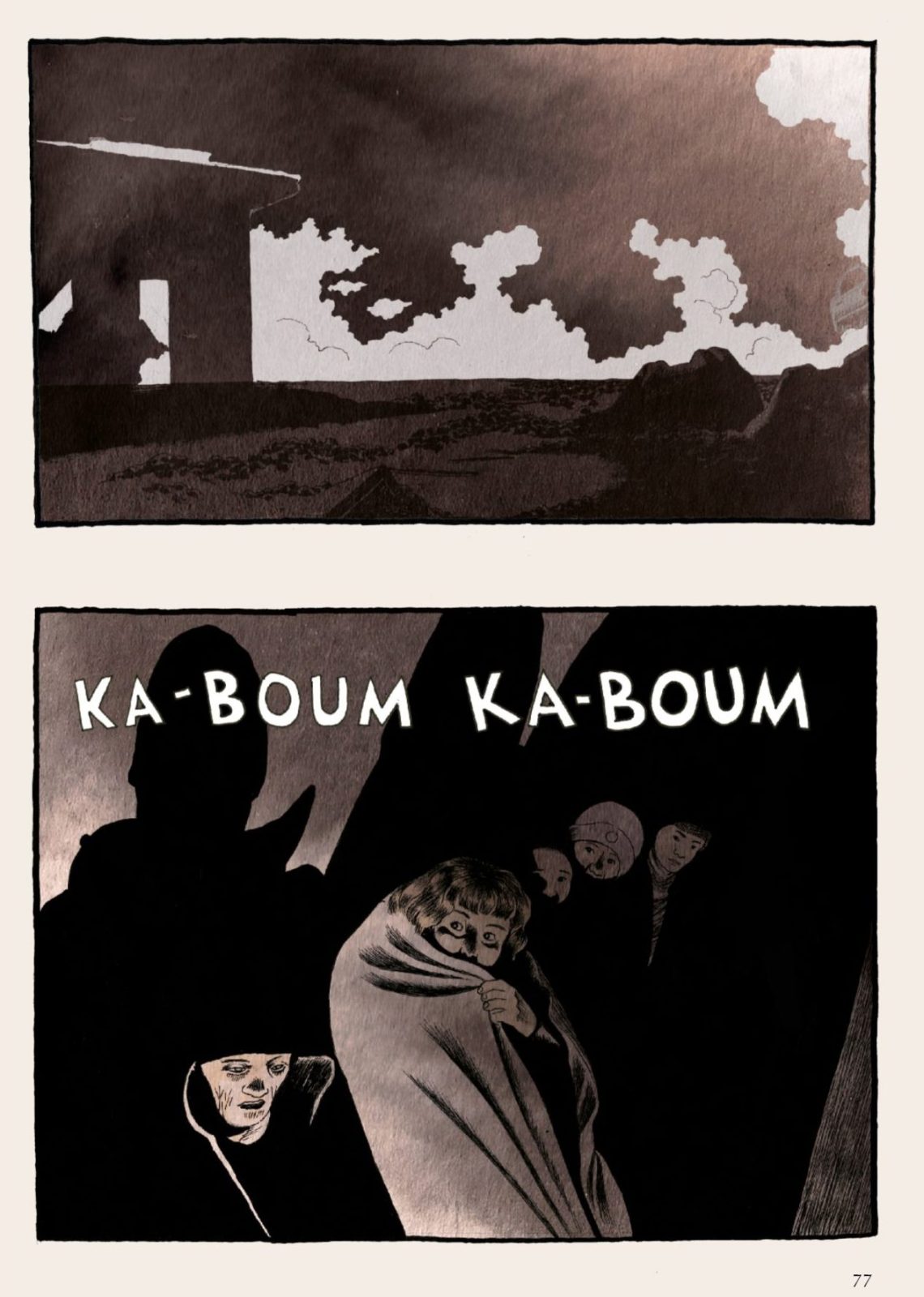

He welcomes me into his studio, a wide and luminous room where the first things I notice are seven or eight guitars in front a couch; a keyboard is there as well, and a huge stereo. It feels like entering the recording studio of a musician. Comics pages must be well-hidden somewhere, but I don't ask about that. Only at the end of our conversation does he show me what he is currently working on. On his iPad he has finished pages of his new stories about Ukraine. A comics version of his Telephone Chronicles - basically an expanded and updated version of Ukrainian Notebook.

We sat in front of the window, both drinking a long black coffee, enjoying the company of Igort’s black cat, whose name I didn’t catch.

-Valerio Stivé

* * *

VALERIO STIVÉ: How and when did your work on The Ukrainian and Russian Notebooks start?

IGORT: It was 2008, I was living in Paris at the time. I had left Bologna in 2001. It was absolutely clear to me that one can tell anything with comics, any kind of story, and speaking with French editors I came up with the idea of telling the story of Anton Chekhov through the stories of his houses.

I’ve always loved Chekhov. He is the inventor of abstract storytelling; the [novella] The Steppe doesn’t actually tell a story, it is rather the description of a place, the steppe. And this reminds a lot of the Art Informel. "The House with the Mezzanine", one of his most famous short works, tells the story of the house rather the story of its inhabitants. Chekhov always dreamt of buying the house that, at the end of his life, he actually bought - the White Dacha in Yalta. He has lived in many houses, and had a peculiar relationship with the houses he lived in.

So I went to Ukraine with the idea of following Chekhov’s footsteps, descending the country to finally reach Yalta, in Crimea. You know, comics have this privilege that I call the “privilege of misery”. Making comics costs nothing. I don’t like living in hotels, so when I travel I usually rent a house. That gave me the chance to experience this strange atmosphere. I saw all these beautiful people there, women and men are so gorgeous, yet so sad. I spent some time in Ukraine, months. There was no hurry. I started asking myself how did this people lived during 70 years of the Communist regime. How was their life? Europeans had such an idealistic idea of it.

Then I called my publisher and I told them I’m going to do a different book. My publishers are really patient, they are used to my impulsiveness.

Who was your publisher for this project?

I was working for the French publisher Gallimard, for its division Futuropolis. I told my editor maybe I’m going to stop people on the streets and talk with them to gather their experiences. At that moment, I had no clue of what the outcome would have been. I still didn’t know I could make comics out of my interviews. It’s not so automatic. So, I remember, I was following the advice of my interpreter to choose the people to stop on the street. And I’d look at their faces, like a cartographer. An artist can see a person’s life by looking at one’s facial signs.

Many times we were sent away, but then I came back, again and again. This process was so interesting, because my work requires memory, even when it comes to fiction - ideas come from things that happened to me or my family.

This time, instead, I had to go out and do my work en plein air, like the Impressionists used to do. Stories came towards me. But I needed to disappear; I was filming the people with a camera, staying in the back, letting the interpreter do the talking.

Nikolaj Vasiljevic, to whom I dedicated a 20-page story in Ukrainian Notebook, sent me away three times before he let me do the interview. And his story was amazing. I saw him in a market crying and selling everything he had left of his life. This man was scared, wary, suspicious. He probably could have thought we were from the secret services. This suspiciousness is very common there, even more in Russia. People are not used to talking freely. I can tell you that because I spent two years in Ukraine. Yet I am not a journalist, my job starts when the journalist’s job ends. I am not interested in a scoop, or breaking news. I’m interested in people.

There is so much humanity in the stories you tell.

That is what I’m after. If I tell the story of a victim or the story of a soldier, it’s still the story of a person… I don’t like this fanaticism we see now, where everyone is rooting for a side. It is disrespectful and amoral. We are clearly witnessing the invasion of a giant nuclear power against a small country, but there are victims also among those young Russian soldiers forced to fight in a mission they were told was supposed to be a military exercise.

What I felt reading Ukrainian and Russian Notebooks is that your books are a mosaic of common people’s lives that tells History with a capital H.

Indeed. That is what I care about. Telling History from the perspective of common people. The history of heroes you read in school books is made by the winners. But I’m interested in a different kind of reality. I want to know what happens when regular people like me and you see their life turned upside down by events that sprung on them with a savagery that they simply cannot deal with.

And when the war started in 2014, you continued following what was going on in Ukraine.

I did several different editions of Ukrainian Notebook and I added new stories to the book over the years. History never ceases to exist. There are so many things that don’t make the news. News titles are shouting information. But then the news doesn't go deep into the facts.

And with the current invasion, you decided to document it daily. Times are different compared to the days you worked on the Ukranian Notebook, information travels so much faster now. I guess you needed to be quicker this time. Why did you decide to work on this project day by day?

Because my phone couldn’t stop ringing. Because I… I know so many people there… I lived there in big cities, like Dnipropetrovsk [Dnipro], in the southeast; I lived in the steppe, near Melitopol. When I interviewed people from a village not far from Melitopol, I sent the book there. The peasants from that village couldn’t believe that a book from France was actually about them. My bond with them is now very strong.

I have friends in Ukraine, half of my family is from Ukraine, I got married there, my wife is from Ukraine, I know that country very well now. And I was not surprised when Russia entered Ukraine.

When all this happened, my phone started ringing, and it just didn’t stop. Those phone calls were full of distress, disbelief, fear. And these people were also demanding information. They know me, they know how I work, they knew I started listening to the BBC, reading the Guardian, and all our newspapers. These people… they were asking questions to me… but I found myself lying sometimes. I found myself watering down what I knew. My wife too… she started losing sleep… it was a nightmare, every day, again and again.

Sometimes five days pass without any contact… they have the Chechens just outside the village… five days is a long time. Who knows what’s going on? Then, right out of the blue, a phone call. They’re alive, they’re fine.

How is everyday life now for the regular people trying to survive war?

There is a Russian paradox, a grotesque surrealism, same as in Russian literature, Gogol, etc.... My friend Anatoly… same age as me… he is sitting around all day with nothing to do. He just watches TV. Ukrainian channels are not available anymore. One day, out of the blue, there are 52 channels, 52 Russian channels… he listens to talk shows where Russians say that Ukrainians cannot be reeducated, and must be eliminated. What could this man think? How can he hold up? Could you? Me, I don’t think I could.

These people don’t have a voice, and I wanted to be somehow helpful, telling the story of a mental institution on the top floor of a building. It is impossible to bring all patients to safety in the shelters when the siren sounds. So they sit around and wait, hoping not to be hit. Or how important a beetroot can be, the idea that starvation can be an instrument of war. But I also told stories of young Russian soldiers.

As Joe Sacco once told me, if you write an essay about this historic event, 300 or 400 scholars would read it. You make a graphic novel, and you can communicate to tens of thousands of readers. This is the magical miracle that our instrument can make. Yet it is considered a medium for simpler minds, or minus habens. I find this so interesting. When you see comics, you lower your defenses. In France, and I think in Italy as well, kids study Ukrainian Notebook in schools.

You go deep into what is really going on there, you tell the most horrible things in your Telephone Chronicles.

I gather information every day. I lose sleep. I shake every time I get news via WhatsApp. But all around us we see so much indifference. We are human, we have to react somehow. After two years of COVID, we are so exhausted. I think this must be the reason why this moment was chosen for this military operation. It’s a plan elaborated over 10 years ago.

Why did you choose Facebook to tell these stories?

Social media [platforms] are narcissism boosters, but I think there has to be some reasonableness. It is important to tell the things we really know. There is so much disinformation and propaganda. Yet Russia didn’t consider the power of social media before this war; it was a mistake, and social media was used by young soldiers as well, sometimes showing how things really were.

A war is perceived by the way it is told. People are very emotional, and this is not a good thing. I think we need to be more sober. I’m working on this new Ukrainian Notebook. Yet telling what I hear and see every day is so hard, because there isn’t enough distance. I shake every time I get new messages.

So sharing the stories from your phone calls on Facebook was like publicly taking notes for your new work.

Yes. This is the use I make of social media. I have such a beautiful interaction with readers. There is J, this friend of mine whose name is Jacqueline Mala, she’s a Ukrainian Jew, who recently started telling me her stories. She is so brave. She is a therapist, she helps refugees giving them psychological support, and she often enters Ukraine bringing food and medical help. These kinds of stories allowed me access to more and more stories of people who live firsthand everything we see from such a great distance.

So I started telling their accounts, not without some kind of fear. These people were afraid of being tapped [i.e. surveilled]. My family have friends in many cities, in Mariupol, Kyiv, Melitopol… all very familiar places to me. I started telling these chronicles because I wanted to be helpful, I wanted to give a voice to those who are invisible, those who don’t have the right the be represented. My purpose is to simply tell people’s stories.

Why did you decide to end your chronicles?

Because I was overwhelmed. I needed to breathe. I just couldn’t make it anymore. I was losing too much sleep.