“Yojōhan-teki ai no nikogori: Kamimura Kazuo, Dōsei jidai” and “Raritta ano ko to hatsu-dēto: Hayashi Sei’ichi, Sekishoku erejī”

From Seishun manga retsuden (Legend of Manga’s Youth; Magazine House, 1997). Later republished as Ano koro manga wa shishunki datta (Back Then Was When Manga Was Coming of Age; Chikuma Bunko, 2000), pp. 167-180.

Writing about two important manga from the early 1970s, Natsume Fusanosuke dovetails his own personal experiences with the works’ themes of young men “cohabitating” with their female partners. First came Hayashi Sei’ichi's Red Colored Elegy (Sekishoku erejī, 1970-1971); and then, about two years later, Kamimura Kazuo’s Live-In Age (Dōsei jidai, 1972-1973). These manga inspired the “cohabitation” boom. Television dramas, movies, even pop songs were adapted from these manga, and the term dōsei (cohabitation, live-in) became quite well-known. According to scholar Ryan Holmberg, Hayashi’s Red Colored Elegy is not only “one of the iconic works of the famous alternative manga magazine Garo,” but also “a work whose combined formal innovations… have no parallel anywhere in comics history.”1 Kamimura’s Live-In Age, again according to Holmberg, is in the mold of dōsei subject matter, but “Kamimura’s direct engagement with sex was one reason his manga was regarded by some people as the more radical of the two. Some even saw it as feminist.”2 Elsewhere, in writing about the lived experiences of Japanese housewives (in his brilliant introduction to the Yamada Murasaki manga Talk to My Back [Drawn & Quarterly, 2022]), Holmberg questions Kamimura’s (and Hayashi's) ability to authentically portray the experiences of women.3 What Natsume explores here, in these twin essays, are the shared aspects of the “live-in” experiences that both Hayashi and Kamimura expressed similarly, although their artistic works could not be more different.

These essays—which we present here as a single, two-part article—were first collected in Natsume’s 1997 book Legend of Manga’s Youth (Seishun Manga Retsuden), from which we have translated other short pieces that have appeared on the TCJ site, including those on Ikegami Ryōichi and Miyaya Kazuhiko. But before that book, they were originally published in Marco Polo magazine (August and September 1994, respectively). “Marco Polo,” Natsume elsewhere wrote, “was a magazine that in short time went belly-up. They ran articles like ‘Nazi Gas Chambers Never Existed.’ My Legend of Manga’s Youth serializations ran there, and, because of the magazine’s termination, so went my column.”4 In most of the Legend of Manga’s Youth essays, Natsume willfully conflates his own experience as a “seinen” (young male) with the young male protagonists in such “alternative manga” and gekiga.

Hayashi’s oeuvre is quite complex, but Ryan Holmberg (again!) has authored numerous critical essays about the avant-garde artist for TCJ and for the English-language editions of Hayashi’s works: Gold Pollen and Other Stories (PictureBox, 2013); Flowering Harbour (Breakdown Press, 2014); Red Red Rock and Other Stories (Breakdown Press, 2016); and the softcover second edition of Red Colored Elegy (Drawn & Quarterly, 2018). Thanks to the scholarship of Holmberg (and his translation of all but Red Colored Elegy among these works), Hayashi is now quite well-situated in Anglophone comics studies. Yet, when it comes to Kamimura, despite his fame and reputation in Japan (and in France), little has been written in English. He probably remains best known in North America for Lady Snowblood (Shura yukihime), an action-packed collaboration with the aforementioned Koike Kazuo, though he left a long, long legacy of popular stories in Japan when he died at the young age of 45. Woefully under-translated and under-studied in English, we hope that this translation of Natsume's reflection on the artist’s exceptionally popular Live-In Age will be one small step to correct that.

As always, we thank Natsume-sensei for his permission to translate his work for TCJ.

-Jon Holt & Teppei Fukuda

* * *

Part 1:

The Jellied Broth Dish of the 4½ Tatami Mat Room

Love always

is filled with some mistakes

and if love is something beautiful

it must be because of

the beauty of this mistake

a man and woman commit

Well… I am a bit ashamed to start off this essay in such a pretentious way. I am guessing there are a lot of baby boomer readers out there who are smiling despite themselves and looking a bit embarrassed.

The above phrases appeared over and over again in Kamimura Kazuo’s Live-In Age (Dōsei jidai), which ran in Weekly Manga Action (Shūkan manga akushon) from 1972 into the next year. Around that time, the work was adapted for a television series, for a film, and it even generated a hit record. “Live-in” (or: “cohabitation”) was a phrase often bandied about at that time.5

1972. It was the year in which the the Red Army [i.e., the Japanese Red Army, a militant communist organization] clashed with Japan’s riot police during the Asama-Sansō Incident; it was the year that saw the start of Prime Minister Tanaka Kakuei and his cabinet; and, in 1973, Minami Kōsetsu had his huge hit record with “Kanda-gawa.”

However, at that time I was totally absorbed in the jazz music of Yamashita Yōsuke, and if it wasn’t jazz, it was generally off my radar. Mainly, what people called “4½ Tatami Mat Folk Music”6 and that world were so pathetic. I just hated that stuff.

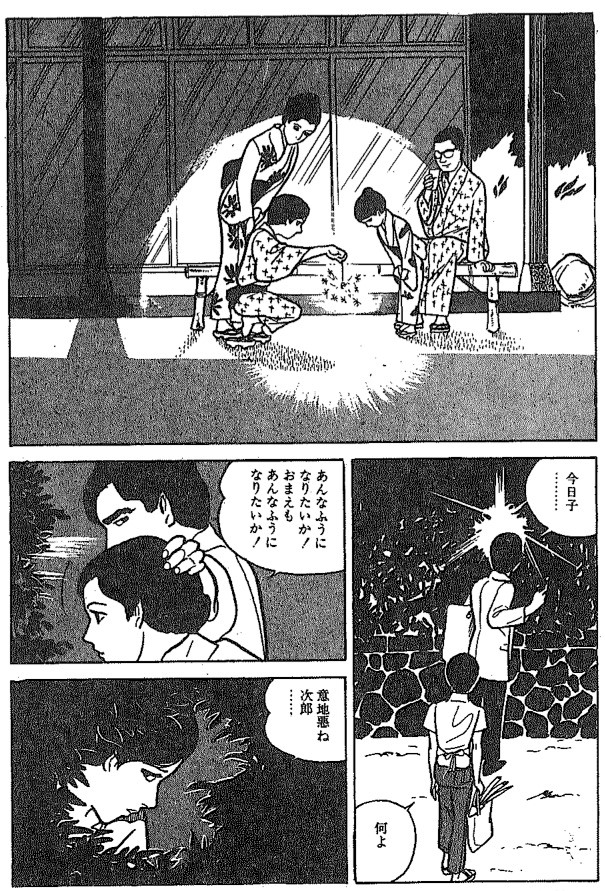

Kamimura’s Live-In Age was a manga that depicted a man and woman with no place to run, with all their sadness, with all their gravitas: certainly, all those things that made sense to us young men (seinen) living in that time. Within its boldly-cut panels, Kyōko and Jirō maintained a constant act of disagreement which they could not avoid - those near-collisions borne from male-female relations. Kamimura had the superb skill of a craftsman, who could draw scenes of everyday life (seikatsu) in minute detail. But though it seems like a mastery of daily-life depiction, what you actually see in this work is the absolute rejection of home life. The term “live-in” (dōsei) was part of the “anti-establishment” feeling then - a kind of regression, or perhaps an escape from daily life, for young people at the time (Figure 1).

Close-ups on the houseplant that Kyōko takes care of. The poor-looking dinner meal of grilled fish placed on their table. Those two-page spreads of the man and woman making love in their pathetic six-mat [tatami] apartment. Narration that quietly appears all of a sudden on a black background, going like this: “Kyōko made no attempt / to see the spring of her 21st year.”

Oh brother. Kyōko was one year younger than me, and she was the same age as a woman with whom I lived together in 1971, the year before the series began to run. At the beginning of the 1970s, the season of young people protesting and rioting in the streets was ending, and so many college students who lived in an apartment did “cohabitations.” I doubt that I could count all my friends and acquaintances who quit college and took up living with their girlfriends while taking up jobs of manual labor, getting pregnant, and then going on to get married, just like that. Well, it wouldn’t be one or two. If either a guy or a gal started to live in a cheap apartment, it really was not all that difficult for the couple to start living together.

As a Tokyoite, I would commute from my parents’ home to my university, so once I reached a point where I was going to live together with a woman, I stated my cohabitation intent to my parents.

“It doesn’t matter anyway, since now that you’ve told us, you won’t hear us out,” my mother said with a forced grin.

My father, for his part, asked me, “Okay, so when do you think you’ll come back?” Without thinking, he was asking me until when would it last.

Since he put it to me like that, I had no choice but to answer, “Maybe I’ll be back home in the fall.” It was a pretty stupid answer.

One day in June, after packing up some clothes and books and putting them in a bag that had my tennis equipment in it, I moved out. I went to a Shinjuku jazz café called Mokuba, where my girlfriend had a part-time job. After she got off work, I would go her apartment with her. In that way, we started to live together.

Until right before we started living together, she had been dating a jazz bass player who was older than her. I talked to this fellow with a sense of determination in me, like I was a person who had made a decision to jump off a cliff. I ended up getting the girl. That guy, who was already both a husband and a father, said to me in a small, weak voice, “Look, there’s no way I can control her,” barely able to crack a smile.

Probably, this woman was testing both me and the other guy. I say this not trying to give to my life some literary embellishment. Those were the facts. Maybe I should say instead that, between men and women, certain recognizable episodes like these will go on repeating over and over. It’s embarrassing.

The two of them

All-waays

Went on living, huuurt-ing each other

It doesn’t get any more direct than that. At least that’s what the Live-In Age film [directed by Yamane Shigeyuki, 1973] and its theme song wanted to express. When these things became trendy, I already had stopped shacking up with that girl. I had intended to split up with her in the autumn of 1971, and I even had the basic pathetic scene for the breakup picked out, so I went to get advice from a senior manga artist friend of mine (Shitō Kineo), whom I looked up to at that time.

He asked me if I thought I would ever meet up with a woman like her again.

“Probably not,” I told him.

(It is not like any young man who is 21 years old would be capable of answering otherwise.)

My friend let out a guttural cry, “You’re gonna regret it!”

And then, as if to add salt to my wounds, he added, “It was the same for me, too…” and he gave me a faraway look.

In the end, we were set to get married after our college graduation, but during New Year’s week in 1972, she began to hemorrhage from an extrauterine pregnancy. Things were very scary there for a while, but we made it through. When I went to see her, right after her hospitalization began, I can clearly remember even now how the hallway had this thick antiseptic smell; I remember going to her and hugging her as she cried.

It really is a gloomy story, and I am sorry to go there, but - well, that was what I was going through when 1972 began and Live-In Age started its serialization.

This is a good time to break down what I think were the two main attitudes people had towards the work. Some really got into it, as they felt that it was a story of themselves. Others thought that they didn’t really want to read the manga of a story they themselves had experienced. I was definitely of the latter camp. After all, I hated that 4½ tatami folk music. I also hated Kamimura’s weirdly flat pictures. Since I wanted to fly away from my always-indecisive self at 400 km per hour, of course there was no way I was going to like this manga.

And yet, I did read it. The reasons are simple. One, all the committed manga readers were reading Manga Action. Plus, I read it because my girlfriend was reading it too. Although I would grumble, saying to myself, “Why the heck do we have to read the story of characters saying and doing the same things we do?” I still got hung up on it, as if I was able to find in it a bit of a trace the person who I was before.

Kyōko and Jirō soon experience both her pregnancy and her miscarriage; Kyōko gets admitted to a mental hospital (gosh, it was a lot like Murakami Haruki’s Norwegian Wood on that point); and, she comes back to Jirō and they start living together again. However, it all falls apart, and they end up separating.

After Kyōko is discharged from the mental hospital, Kamimura draws the following episode:

Kyōko puts on some lipstick, invites Jirō to have sex, and bites on his ear while he is working. (Come to think of it, Jirō is an illustrator.) “You were not that kind of woman,” he says, blowing her off rudely (hey, hey now!) and going out for a walk. He meets a woman in the park and they get in a boat together. When he comes back to his now-darkened apartment (by the way, Jirō was wearing jeans and geta sandals), Kyōko turns around to face him. Her whole face has been smeared thick with the lipstick. Tears flow from her white, pupilless eyes (Figure 2).

Folks, she is not rolling her eyes to scare him. It is a metaphorical gekiga expression to recreate crazy dot-like staring eyes. Some people might like or hate the way that Kamimura will parse out small detailed moments of time like this. Say what you will, but he really is good at doing it.

The 1960s are when we begin to see manga artists like Nagashima [Shin’ji] and Tsuge [Yoshiharu] dispense with the way that manga before had showed time in dramatic and grand narrative staging to instead tell the stories of everyday life with a kind of slow, walking pace, like that of their readers. In Live-In Age, Kamimura took their approach away from a faction of the manga fanbase and made it a normal thing for the average seinen readership.

It has been 20 years [from 1994] since it first came out, and as I pick it up and read a part of it again, I feel that I left some things behind that were really important to me, and that I can never get them back. I suppose that anybody in any generation will look back to that time in their youth and feel the same kind of thing, but I don’t quite understand what it exactly is. What Kamimura did was sort of to take all those moments that would make us feel that way, and cook them down into a stew. That’s what his Live-In Age is like.

Part 2:

First Date with the Trippy Girl:

Hayashi Sei’ichi’s Red Colored Elegy

In my previous essay about Kamimura Kazuo’s Live-In Age (Dōsei jidai), I wrote that I wasn’t all that fond of it.

It is not only because I myself had been in a live-in arrangement with a woman, but I had other reasons to see the whole “Live-In Age” boom as something painful.

Two years before Kamimura started serializing his Live-In Age, Hayashi Sei’ichi’s Red Colored Elegy (Sekishoku erejī) had run in the pages of Garo for one whole year, starting with the January 1970 issue. Hayashi’s experimental work was at the very tip of the vanguard. And, for the young men (seinen) of the manga world at that time, none of us could take our eyes off it. Moreover, this manga too depicted pains from which a man and woman living together cannot escape.

In 1970, I was a second-year university student, and it was a period where I was only half-recovering from a depressed state that made me feel like I was crawling through the mud and muck. The girl with whom I would eventually end up living together was somebody I met towards only at the end of that year, but, for me in 1970, the idea of the “live-in” or living together was something totally unrelated to me. Therefore, I had no reason to get hooked on [Hayashi’s] manga with its idea of a man and woman living together [out of wedlock] and all the troubles that come with that.

Back in 1969, when I became a college student, there was a girl from the same department that I became keen on - but even into 1970, I still liked her so much, and yet I hadn’t made my move to tell her. These were romantic feelings only slightly more advanced than the dreams of a teenaged boy. In 1970, I took this girl to see a stupid [American] movie that had the dumb title The Strawberry Statement (1970; Japanese title: Ichigo hakusho). The movie later spawned a popular Japanese song called “'Strawberry Statement' One More Time” (“‘Ichigo hakusho’ o mō ichido”) [by Matsutoya Yūmi, later known as Yūming]. Once I heard about that, I got so mad I nearly fell out of my chair and I cursed it, saying to myself, “One more time? No fucking way I want to see it one more time!”

Anyway, most likely, Hayashi’s Red Colored Elegy was the first long-running manga that took up the theme of unmarried couples living together (dōsei). That’s why, later, when [Kamimura’s] Live-In Age became a big hit, I thought, “What the hell? This is just reheated leftovers!” It probably wasn’t unnatural for a punk university student to think that. (After all, the master Kamimura Kazuo himself publicly admitted it.) However, Red Colored Elegy didn’t become a big hit like Live-In Age did.

Hayashi’s manga depicted the most basic events in peoples’ daily lives, and yet he kept it running with a lot of images that had a metaphoric visuality that, on first glance, seem to have no coherence, so it was seen as a difficult manga on the very edge of the avant-garde (Figure 3). Even so, its extremely dark and heavy feeling was just what young men liked with their tendency to agonize over everything (and I should add a note here that the three buzzwords for young people at that time were “heavy” [omoi], “dark” [kurai], and “agony” [kunō]). I too always regularly purchased Garo, and I loved reading Hayashi’s manga.

For example, there is a scene in which the protagonist, Ichirō, goes out in the rain in search of his live-in girlfriend Sachiko (even though he has no idea where she is). At one point, the boyish face of a fortune god suddenly manifests on his umbrella and he asks Ichirō, “Where're we going?” “She’s somewhere getting rained on.” (Figure 4.)

If this was done by a normal manga storyteller at the time (well, even now this is the case), such a wild and crazy scene could only happen in a yōkai (supernatural creature) manga, so Hayashi’s readers have no idea what is happening. And yet, the reader gets the feeling that what we’re seeing visualized is the antsy mentality of the young male character. It really sticks in your mind.

For me now to comment on this part, it is clearly a visual metaphor for the way in which Ichirō talks to himself. The way that Hayashi can create these unique contradictory feelings or a sense of discord through metaphorical images like that is exactly what made his manga so appealing. At the time it came out, I was drawn to his work subconsciously, and I would have to say it was fascinating, but I would not have been able to explain why that was so. These were the weird experiences that I regularly enjoyed reading in his work.

In order to make his pictorial metaphors come alive and talk, Hayashi actually did not need that many words. His dialogues were cut into short bits, so if he took out the lines of dialogue, you would have had no idea what’s happening. They were out of context, but each and every part had its own intense reality. In the scene in which Ichirō announces the end of their relationship, telling Sachiko, “Let’s break up,” for four panels after that, pages of animation sheets go flying around (and, by the way, both the guy and the girl are animators). Sachiko then says to him: “I didn’t think you could say it...”7

The indifferent tone of her words makes the reader sense what her raw voice was like. Actually, if one looks at the readers' column in Garo from back then, many of the letters that saw print reveal that the fans of the manga were not reading for Hayashi Sei’ichi so much as they were admirers of Sachiko.

It was only the year after the series finished its run that I realized how deeply the reality of that kind of dialogue had sunk into my being. It was then that I began to hang out at the workplace of a manga artist who was over 10 years older than me. There were about three or four of us—all the same generation—who would go to his place, but among them was a girl named E. She, more than anyone, seemed not to have a whit of interest in me.

“You really are a typical botchama [spoiled boy] who doesn’t know anything about the world.” That was her impression of me, which is something I heard only at a later time.

In April 1971, on my campus there was a concert by the Kikuchi Masabumi jazz quintet. I was just then slowly coming out of my depression, and was getting the point where I finally got back the strength to try asking out a girl. So, I invited this girl, E., to go to the show with me. Actually, I asked her to go out because I was wavering over asking a girl from a jazz café located in Shibuya Dōgenzaka. So, it wasn’t that I “really really liked” this girl, E.

On the day in question, as I was waiting at our meeting place, I saw her walking in my direction like a drunken crab. She was wobbling left and right, barely able to walk toward me. Thinking that maybe she wasn’t feeling well, without missing a beat I put my arm around her waist to support her - but now that I think about it, it really was a move far bolder than anything I was normally capable of doing.

For the longest time, I had been just an innocent boy who had been unable even to speak of his love. For E., I looked like a person who knew how to play the game. After all, we don’t know what works well and what does not. Anyway, after seeing her off to her place that night, we began to regularly see each other - and, later that summer, we ended up doing the “live-in” together. I shouldn’t say this publicly, but at that time when E. was wobbling around, it was because she was trying to dose herself with sleeping meds, her intent beyond just using them to sleep at night. Well, she was quite a trippy girl.

Whereas before I had been in just some innocent romance, which itself had been only a step above the [childish] adoration for girls, here I had gotten myself got into a real, severe, and dirty affair. It was during this time, as I was rereading Red Colored Elegy, that I found myself moved so much by the supreme reality of men's and women’s relationships found in Hayashi’s manga.

For example, Hayashi draws in one panel an image of Sachiko, who waits completely still for Ichirō to return home from his parents’ place. There is nothing in the room, and Sachiko just holds her hands up above the electric heater (ah, so pathetic!) and her back is hunched. The way that Hayashi portrays girls looking like that always breaks your heart.

One time, I had been away on a trip, and when I came back home, E. said that while I was gone she would wait for me and smell me from my sweatshirt. Her adorable act really pierced me to my bones and totally captured my heart. Sachiko’s appearance made me relive those feelings from my own life.

The way Sachiko ambles about in her pajamas with those eyes of hers that are just eyelashes without pupils; that always slightly-hunched back of hers; and those small but well-shaped breasts she had. Those breasts were outside of the normal manga code that symbolized a girl. Sachiko conveyed a real cuteness in her form - which, at a glance, looked like it could be seen in any girl anywhere, but hers was a form that only existed there (Figure 5). There was no one who could beat Hayashi at that kind of depiction.

That, or the sight of both Ichirō and Sachirō always drawn on their thin mattress looking so pathetic, thrashing about (Figure 6). The pain shared by this man and woman cannot have any release. That is what Hayashi could convey to readers with just a few panels and drawings.

Once manga freed itself from the influence of theatrical drama, it found a way to perfect the depiction of such everyday scenes; and manga artists kept interweaving images with rich symbolism into those scenes. Hayashi discovered the prototype for doing just that.

For a true manga aficionado reading at that time, like me, there was no way a person could read Kamimura’s Live-In Age and innocently enjoy it.

* * *

- Ryan Holmberg, “Seiichi Hayashi’s Nouvelle Vague” in Hayashi Sei’ichi, Red Colored Elegy (softcover edition, Drawn & Quarterly [2018]), p. 239.

- Holmberg, ibid., p. 279. Note that Holmberg translates the title Dōsei jidai as "The Age of Cohabitation."

- Per Holmberg, Yamada’s manga "shimmer with a degree of realism found nowhere else in manga at the time, further enlivened by pithy verses minus the clichés of flowers and seasons often plied by male cartoonists, like Hayashi Seiichi (an influence) and Kamimura Kazuo, who presumed to speak for women’s experiences.” Ryan Holmberg, “The Life and Art of Yamada Murasaki” in Yamada Murasaki, Talk to My Back (Drawn & Quarterly, 2022), xvi.

- Natsume Fusanosuke, “Hayashi Sei’ichi: Sekishoku erejī,” Fūun manga retsuden: ima yomu manga 116-satsu (Shōgakukan, 2000), p. 108.

- [Translators’ Note] Ryan Holmberg offers an excellent discussion of the term dōsei and the “cohabitation” boom in Japanese culture in his introduction to Red Colored Elegy (softcover edition, Drawn & Quarterly [2018]), pp. 241-249. Briefly, Holmberg identifies dōsei as signifying: "a young, heterosexual couple living together and having sexual relations without being married, and likely without the knowledge or approval of their parents."

- [Translators’ Note] “Yojōhan” or “4½ Tatami Mat” is used to describe the size of a room, which can fit four and one half tatami mats. The size of the room is roughly 7-8m2 (the size of a tatami mat is slightly different in the eastern regions and the western regions of Japan). In the 1970s, this was the typical size of a room for impoverished youths, and the term came to represent the time of one's poor but youthful (seishun) days. In “Yojōhan Folk” or “4½ Tatami Mat Folk Music,” which is a genre of music that became popular in the 1970s, musicians typically sang about their impoverished but lyrical lifestyle, such as a life of two lovers in a yojōhan room.

- [Translators’ Note] Hayashi, Red Colored Elegy (softcover edition, Drawn & Quarterly, [2018]), pp. 193-195. All quotes from dialogue employ the translation by Taro Nettleton from that edition.