It was not uncommon in kashihon manga, especially those authored by celebrities like the Gekiga Studio’s members, to find short interviews with the artists chatting about their hobbies and favorite manga. They are short, rarely exceeding a page or two, and for the historian they are practically worthless, providing, at the most, personal color but very little in the way of insight into the cartoonist’s working methods or artistic philosophy. Mass print youth monthlies also dabbled in Q&A with their contributors, but once again they rarely exceed the purpose of engendering chummy familiarity with the magazines’ child readership.

I am not sure when the first substantial interviews with manga authors were conducted and published. When, that is, cartooning in Japan was considered interesting and culturally significant enough to warrant public revelations regarding what went on inside its creators’ heads. “Adult manga” artists were frequently interviewed for features in news tabloids in the 50s, but I don’t recall any extended transcripts, just quotes worked into articles or serving as captions to photographs showing the artist bent over his or her desk or laughing loudly (cavities showing) over rounds of sake.

Garo was possibly a leader in this department as well. Beginning in 1968, Garo frequently printed long-format interviews between its artists, as well as with critics and creators in other fields. Garo must have published at least twenty such interviews in the late 60s and early 70s. Together they suggest a new understanding of what a cartoonist can be and what a cartoonist does.

Fifties kashihon and adult manga frequently showed the cartoonist as a beret-topped bohemian. The brief snippets about the cartoonist’s daily life that you get in those interviews help round out that picture, which emphasized not poverty but dapper professionalism. You also find a significant amount of “cosplay” in these segments. Members of the Gekiga Studio (especially Satō Masaaki) liked dressing up as hardboiled private eyes and Nikkatsu style gun-toting gangsters. Tatsumi Yoshihiro’s gritty boxing manga from the early 60s often open with photographic spreads of the artist in training.

In Garo, the image of the cartoonist as an artistic bohemian trickled in through figures like Takita Yū, Tsuge Yoshiharu, and Nagashima Shinji, and then took a new form around the work of Abe Shin’ichi, Suzuki Ōji, and Furukawa Masanobu in the early 70s. But there’s never any dressing up, no sartorial displays of the cartoonist’s special status. If the daily life of the cartoonist was important, that had to be proved through the work, namely in the diaristic “I-novel” genre that Yoshiharu popularized. Like interviews in other manga publications, Garo frequently dipped into the artist’s personal likes and dislikes, but usually not as an end in itself, rather to segue into wider and more abstract discussions about the artist’s relationship to art, pop culture, and historical events. Cartooning was positioned in Garo less as a job or a lifestyle, and more as an activity driven by ideas, with its practitioners capable of holding their own on matters of culture and history with people in established categories of intellectualized cultural production, like cinema, theatre, painting, or poetry.

This upward flattening – that manga was one artistic medium amongst others, and that a manga-ka was one type of artist amongst others – might be read alongside attempts at the time to use new concepts in art and cinema discourse to interpret experiments in manga (for example, “eizō manga”), and manga authors’ incorporation of aesthetic strategies from other media like graphic design and New Wave cinema. This refashioning of what a cartoonist could be and what the tools of the cartoonist were represented a major step in the cultural legitimization of comics in Japan, and it had less to do with connoisseurs arguing for the artistic or “literary” merits of the medium than a proactive de-professionalization of the category “manga-ka” in line with the open-mindedness that the discourses of “intermedia” and “Pop” implied.

Anyway, that is how it looks from the outside. However, to put things in this sexy 60s manner is to misrepresent, in a fundamental way, the construction of Garo as a magazine. As I explained last time, even though the sprit of late 60s avant-gardism thrived in certain Garo artists work, one cannot say the same for the magazine as a whole. Garo had cutting-edge content, but the overall construction of the magazine was rudimentary. There is no design to speak of, just an assembly of (for the most part) good-looking comics supplemented by a few pages of plainly laid out text. In an age of experimental book and magazine design, Garo looks not simple but bare, like an unfurnished office.

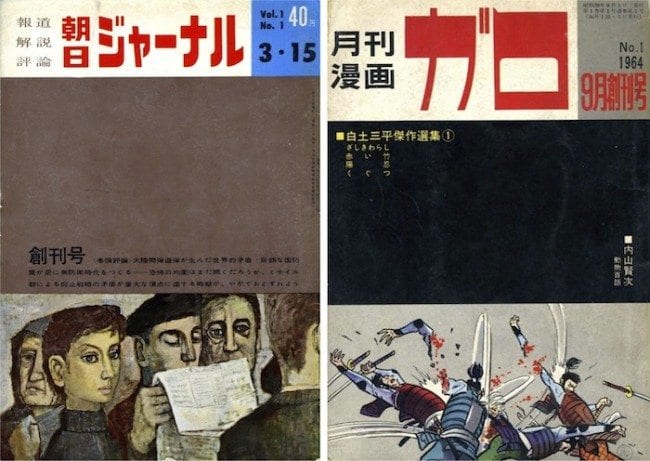

Yet, within the context of manga periodicals, Garo was a novel institution. This thanks not just to innovative art, but also a set of overlapping editorial policies that other magazines could not afford to employ either individually or together. Shirato Sanpei co-founded and funded the magazine in its first year, and to his influence (and that of his studio, Akame Pro) one can attribute the aggressive political commentary, the counter-pedagogical content, and the original modernist cover design, which was modeled upon that of Asahi Journal, a popular left-leaning weekly founded in 1959 and avidly read by intellectuals and students. Nagai Katsuichi was the other founder and the publisher of Garo, and to his influence one can attribute the magazine’s continuity with kashihon publishing, a field in which Nagai had been active since the mid 50s. However, when it comes to the interviews, the artistic content, and the various other things that made Garo the thinking person’s manga magazine in a New Left “countercultural” vein, neither Nagai (who was reportedly cold on arty and intellectual things) nor Shirato (who might visit Seirindō once a year) can claim credit.

Between 1966 and 1971, the managing editor of Garo was Seirindō’s only true full-time employee, Takano Shinzō (b. 1940). “Aside from the accounting, I did everything,” Takano told me when I interviewed him in 2012, from taking samples to the distributors and making space in the storage room when returns arrived, to selecting new work and composing the supplementary textual material. Had things been left to Nagai and Shirato, Garo probably would have withered away as a kashihon manga anthology masquerading as a newsstand magazine, or been bought up and eviscerated by one of the big publishing houses (in fact, Shōgakukan tried to do so in 1967).

While Takano was much impressed by Shirato’s The Legend of Kagemaru (Ninja bugeichō, 1959-62) as a college student, and reports joining Seirindō in September 1966 for the chance to work with Shirato and Tsuge Yoshiharu, his editorial sensibilities were formed outside of manga publishing. In 1963, Takano began working for Nihon dokusho shinbun (Japan Reader’s Newspaper). Begun in the 30s as an industry paper of the Japanese book trade, by the mid 50s Nihon dokusho shinbun had achieved a reputation as a must-read publication for progressive intelligentsia and university students, and this at only eight pages per weekly issue. Though financed mainly by advertisements from publishers, the newspaper covered film, art, and politics (Sartre, Mao, and Ho Chi Minh were frequent subjects in the mid 60s), in addition to books and magazines. It was respected as a platform for sharp criticism and heated intellectual debates on cultural politics, counting amongst its contributors giants like Maruyama Masao, Takeuchi Yoshimi, Hanada Kiyoteru, Yoshimoto Ryūmei, and Oe Kenzaburō. It was known as a place where writers could speak their mind. When, in 1964, an anonymous columnist wondered if a certain, sickly-looking member of the Imperial family (not the Emperor) would be able to get it up on his upcoming wedding night, Nihon dokusho shibun got as much flak from its readership for offering an apology as it did from the rightwing for insulting the nation’s soul.

Assessing the paper retrospectively, writers could become breathless. After its folding in 1984, Sano Shin’ichi, one of Japan’s top writers on political and business matters, wrote the following: “Like an oracle echoing from the craggy mountaintops of the Shōwa intelligentsia, this newspaper committed itself to the humble task of continuing to glorify print culture. It was called the newspaper of newspapers, the publisher of publishers. Its headlines were like slogans of the campus festival and the placards of the student movement, casting a spell over leftwing students and literary youth, and achieving a circulation of close to 100,000 in its heyday, which was ten times what it claimed when it folded. In the job-hunting season, some three hundred students lined up before its editorial offices in Ishikiribashi, in Tokyo’s Bunkyō ward.” Takano had landed a highly coveted and competitive job.

For manga criticism as well, Nihon dokusho shinbun was an important venue. Intellectual journals, weekly news magazines, and other trade papers had been increasing their coverage of manga since the late 50s. While debates about the supposed demerits of comics within the akusho tsuihō undō (“campaign against bad books”) was the occasion for many such articles, in the early 60s a more positive and work- and artist-centered approach developed around the politics and meaning of violence in The Legend of Kagemaru. As mentioned above, The Legend of Kagemaru was also Takano’s point of entry into manga as an intellectual enterprise. After he joined the paper in 1963, he and another editor Yamane Sadao (who became a well-known film critic) began interviewing and writing articles on their favorite manga authors from both the kashihon and mass print circuit. They hired writers associated with the Contemporary Children’s Center (Gendai kodomo sentaa) to do the same, resulting in some of the earliest published articles on Mizuki Shigeru, Satō Masaaki, Umezu Kazuo, Chiba Tetsuya, and George Akiyama. When the United States commenced Operation Rolling Thunder in March 1965, Takano knocked on Shirato’s door to ask him for his opinion on the matter and its implications for Japan. A week later, Shirato delivered a tirade against American imperialism and Japan’s support of it – one of the few published texts on political matters by the artist. When Garo turned a year old, Takano commemorated the occasion with an overview of the magazine and Shirato’s philosophy, for which he interviewed the artist again.

Given the amount of ink spilled over The Legend of Kagemaru in the early and mid 60s, the simple fact that Garo was Shirato’s magazine probably guaranteed that it would be talked and written about. But that talk and writing became an integral feature within the pages of the magazine itself owes to the fact that an editor from a critical review – with a college education, with knowledge about New Left culture and intellectual debates, and with writerly aspirations himself – had a grip on Garo’s helm. Takano was also responsible for helping build discourse around Garo through supplementary publications. In 1967, Seirindō published The World of Garo (Garo no sekai), a collection of articles about Garo and its artists reprinted from magazines (including Nihon dokuhso shinbun) and college newspapers. Put together by Takano, this cheaply produced booklet is a must-have for any student of early manga criticism, though its primary purpose was to hook advertisers, by saying, hey look, smart people and university students are crazy about us, so join the bandwagon. Also in 1967, Takano (under the penname Gondō Susumu) co-founded Manga shugi (Manga-ism), probably the world’s first journal of long-format comics criticism. More than half of the essays were on Garo artists. Yamane (Takano’s former colleague at Nihon dokusho shinbun), Ishiko Junzō (an art and manga critic who I think Takano first met through Nihon dokusho shinbun), and Kajii Jun (one of the first historians of kashihon manga) were the journal’s other founders, and were frequently involved in interviews and writing articles for special supplementary issues of Garo dedicated to the work of individual artists.

Clearly, a rich history could be written by fleshing out the above. My intention here was simply to give you a sense of how Takano’s presence introduced into Garo a way of production beyond Shirato’s or Nagai’s imagination. Garo as an object and platform of discourse, Garo as a genuine magazine rather than just an anthology of comics, Garo as a cultural “phenomenon” – owes a lot to Takano’s influence. And when it seemed to Takano, in late 1971, that Nagai was no longer interested in supporting this vision (the breaking point was Nagai’s censorship of an image of the Emperor in one of Tsuge Tadao’s stories, an episode described in my essay in Trash Market), Takano left Seirindō and began his own periodical, Yagyō, appropriating many of Garo’s edgiest contributors and reserving many pages for artist interviews and serious criticism. If Garo seems a substantially different publication come the early 70s, the reason is not just that the 60s “season of politics” had ended, but that one of its editorial brains had defected.

As promised last time, translated below is an interview between Hayashi Seiichi and Sasaki Maki, published in the February 1969 issue of Garo. Of the interviews published in the magazine, this is not one of the best. But it’s insightful, and has the merit of being one of the few where two of the magazine’s artists talk to one another at length. Though many of Hayashi and Sasaki’s references will be opaque to non-Japanese (namely the names of writers and musicians), I’ve decided to add only enough commentary to make clear that Hayashi and Sasaki were as (if not more) interested in the poles of pop culture and personal identity, and they than they were in the hot nodes of 60s radical politics and the nouvelle vague.

A couple of things to keep in mind. While the enka versus Beatles segment marks the most obvious divergence of taste between Hayashi and Seiichi, it is important to remember their professional backgrounds. Sasaki was an art school drop-out (Kyoto University) with no professional artistic experience until after his success in Garo, while Hayashi had worked for six years as an in-betweener and key frame artist at Tōei and KnacK before turning seriously to manga. That will help make sense of why they butt heads in the beginning over the relationship between art and commerce, which in turn is important for how one defines and thinks about “avant-gardism” in manga.

Note Hayashi’s mention of director Suzuki Seijun’s name in this context. It occurs only in passing here, but Suzuki’s work, and his ability to incorporate striking and artistic effects into the straightened program of genre filmmaking, was a major inspiration for Hayashi, as it was for many creators and critics at the time. It was also a political issue, for in April 1968 Suzuki was fired from Nikkatsu for making “incomprehensible” films that were a “disgrace” to the studio. Most people take this to mean the visually baroque pictures spanning Tokyo Drifter (Tokyo nagaremono, 1966) to Branded to Kill (Koroshi no rakuin, 1967). When a cinema club tried to mount a retrospective of Suzuki’s work in protest, Nikkatsu refused to lend the films, turning what was a personal issue into an occasion for protest against the rule of capital in the film industry.

For Nikkatsu, Suzuki was indulging in opaque and superfluous art techniques when he should have been focused on entertaining the masses in late-night double-header screenings. For critics, Suzuki represented how art and commercial entertainment need not be exclusive, in fact how they could feed off one another within a single person’s oeuvre, even within single films. One can identify specific motifs and design ideas Hayashi probably adopted from Suzuki. More fundamentally, like Suzuki’s films, the strongest of Hayashi’s manga often integrate experimental flourishes into what are otherwise stereotype-ridden genre stories. Red Colored Elegy is the obvious example, but there are other works closer to Suzuki in sprit. Take, for example, his “Flower Crest” series (“Hana no monshō,” November 1968-January 1969), about a boy who seeks revenge against an errant uncle, with frequent references to yakuza film and bizarre graphic breaks in the diegesis. Hayashi was probably finishing up this work when the present interview was conducted, at the very end of 1968. For a mainstream venue like Weekly Asahi (as we saw last time), Hayashi’s manga represented newfangled incomprehensibility. But as his exchange with Sasaki attests, the artist himself was thinking about ways in which experimentation and excess could form an integral part of an expanded model of “mass entertainment.”

Thank you to the Hakuho Foundation for their support while writing this essay and translating the text below.

"Singing Our Own Song," Garo (February 1969). Translated with permission of the artists.

"Singing Our Own Song," Garo (February 1969). Translated with permission of the artists.

Sasaki Maki was born in Kobe, and is 22. Hayashi Seiichi was born in Tokyo, and is 23. Both of their work has been getting attention as “an expedition into a new world of manga by those with no experience of the war.”

Since Mr. Sasaki happened to be in Tokyo, we quickly organized a talk between him and Mr. Hayashi. The conversation was all over the place, so it’s hard to say that it smoothly followed a single theme. But let’s lend our ears to what they had to say nonetheless.

The Goal and Purpose of Manga

Sasaki: I had previously published “A Familiar Topic” (“Yoku aru Hanashi,” Garo, November 1966) and “An Unknown Star” (“Mishiranu hoshi,” Garo, February 1967), but I feel with “A Dream in Heaven” (“Tengoku de miru yume,” Garo, November 1967) that I reemerged reborn. That’s why I think of “A Dream in Heaven” as my first work.

Hayashi: I’ve made a living in animation, when all of sudden I wanted to start making manga. Maybe it’s that I wanted to say whatever it was that I had wanted to say. I wasn’t really thinking of what the goal or purpose of manga was. I don’t think that’s changed even now.

Sasaki: When manga is used for satire, manga is being used as a means. Manga isn’t the goal. It’s the means by which to create a tangible effect. Thus, after a certain amount of time has passed, that purpose comes to an end. I respect that kind of manga. At the same time, I also respect manga that is part of the wider field of using images (eizō). Right now, I’ve ended up putting more emphasis on the latter.

Hayashi: In my case, if you ask me why I make manga, it’s simply because there was something I wanted to draw so I drew it. If you force me to explain it, I think I’d say that drawing manga is a kind of “violence.” Giving “birth” to something is violent, right? If you asked me why I gave birth to something, I’m not sure I could answer that.

Sasaki: In the case of novelists, take Oe Kenzaburō. While he writes novels, to make a living he also writes columns and essays. I would like satirical manga to play that role for me, for my own personal balance, as Oe would say. (Laughs) If I were in that situation, then I would commit myself totally to the means, because that’s where the strength is. Living with the times, and becoming meaningless with the passage of time, that kind of manga is fine with me. But you have to do it wholeheartedly, that kind of satirical manga.

Hayashi: Sometimes people call my manga and your manga “difficult,” but I don’t think that applies to either of us. Everyone who makes work of course has their own way of doing things. It’s probably like this with anything, but there’s this idea that there’s a line that links things, that says what 1 + 1 is. When someone says something is difficult, it’s because they are trying to understand it with their 1 + 1 formula, though it can’t be answered that way. Maybe everything is like that. For some people 1 + 1 is 2, for someone else it’s 5, and for another person it’s 10.

Sasaki: They get confused. (Laughs) What I was most happy about with this essay about my work in the Ritsumeikan University newspaper, when I really thought that the person had understood me, was when they wrote that the importance of Sasaki’s manga was that it succeeded in freeing itself from this cramped space where manga is understood within the confines of language. For me, if something can simply be converted into words, then there’s no reason to draw it as manga. It’s the same thing I think with painting or music. Manga or cinema or music scoops up whatever words cannot contain, whatever escapes the mesh of words. Precisely because they are sifting through what spills out beyond words, you get these readings where people are not sure how to interpret the work or explain it in words.

Hayashi: Try as you may to explain the pictures, they are just a means.

Where Creators and Readers Diverge

Sasaki: Hayashi, your earliest manga were schematic, don't you think? You showed your hand, and that wasn’t interesting at all. The father is a symbol of the war generation, the child who leaves home is a symbol of the postwar generation, . . . and the giant fish is the USS Enterprise.

Hayashi: No, it’s not. To put it simply, the entirety of The Giant Fish is the nation. It’s not that the fish itself is a symbol of the nation or anything.

Sasaki: But that’s what happens, one ends up trying to match things up. This means this, that means that.

Hayashi: Well, you know this happens often. You make some gesture, it gets associated with some anti-establishment movement, and people think the one is equivalent to the other. Take your work for example. If someone finds something in one panel that speaks to them, then that changes the tone of the entire work for them. The artist might say, no you got it wrong, but it’s not like we can go into the audience and kick that reader out.

Sasaki: In my case, there are intellectual readers. They will look at a panel that has no meaning and read something deep into it. I really hate that. They debate over these empty theories, you can watch them at it in these intellectual salon type journals. The kind of people who will look at a rock and won’t stop until they find some sort of philosophical meaning in it. That’s why I intentionally plant meaningless panels that look like they suggest something. That kind of person that sees that and feels that it means nothing, that’s the kind of reader I embrace. The kind of person that is convinced that there’s a deep meaning in it, I don’t trust them. Let’s criticize intellectuals. (Laughs)

Hayashi: Do you ever feel that you want readers to understand your work?

Sasaki: I guess I do, I want readers to understand. If I didn’t, I don’t know why I would put the effort into creating manga. After all, I am taking the trouble to ink my pages, publish them, and show them to readers. But that doesn’t get expressed well in my work. It gets distorted, and my work makes it look like I couldn’t care less.

Hayashi: I think we’d be lying if we said we don’t care if people understand our work. There wouldn’t be any reason to publish what we make. What’s great is when someone says they can connect with something in your work, even though they might be a total stranger. I’m not sure how to explain that feeling.

Sasaki: The fashionable way to put it these days is, “What does the reader mean to you?” (Laughs) But like with your work, I only started getting into it once I stopped being able to read into it.

Hayashi: Do you mean you were able to find that “something” that speaks to you, which I was just talking about? With your work, sometimes I start reading from the middle. Or like the third panel from the end will provide a key to solve a puzzle.

Sasaki: Exactly, like you read only every other line.

Hayashi: It’s not that there are some images that make sense and some that don’t. In many pages, it’s like space has been cut up and then re-condensed inside a given span of time, and the pages progress that way. That’s what’s interesting.

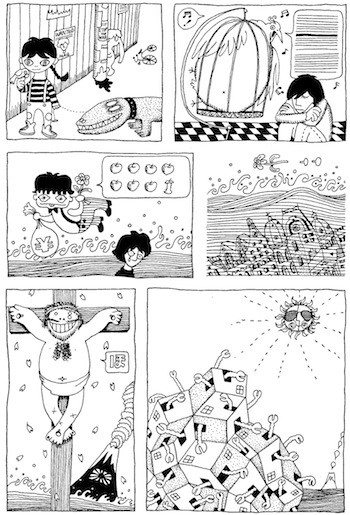

Sasaki: I’m giving away the secrets of my trade, but when I draw I don’t think about page order, I just draw one page a day. Afterwards, once I think I’ve finished saying whatever it is I wanted to say, I reshuffle the pages like pack of cards.

Hayashi: My friend said the same thing. Sasaki draws like he’s writing a diary and just publishes what he has collected after a certain number of days.

Sasaki: So when’s its finished, the order inside a single page is fixed, but even that I wish I could change. Ideal would be having one panel per page, then being able to shuffle them like cards. I want to make a movie, because I want to be able to cut and connect different segments of film.

Hayashi: You find the act of editing interesting? (Laughs)

Sasaki: I like the lack of commitment (musekinin).

Hayashi: Do you think it’s possible to reorder the pages once the editing is finished?

Sasaki: I think so. I change the page order right up to the point when I send it in. Of course, each work exists independently.

Who are your Friends, Who are your Enemies?

Sasaki: When publishing a work, one can imagine all sorts of troubles coming up. But I have no problem with compromise. That is, as long as I am guaranteed a publishing outlet that let’s me do exactly what I want to the very end. If I’m guaranteed that, I’m happy to compromise on other things. If I didn’t have that . . . well, that’d be painful. (Laughs)

Hayashi: When you say a place that will let you express yourself, I think that can come in many forms. I don’t think there’s such a thing as a venue that will not let your express yourself whatsoever, no matter how intricate the situation might be, even if you’re made to move along a single track. Even in making movies, no matter how hard the company tries to force you to do something, there are areas where they simply cannot invade. So to completely lose the ability to express oneself? I don’t know if that’s possible. I don’t know if anything can be enclosed so strictly. Even if they tell you to do such and such with a specific script, there’s still space where you can put in part of yourself. Even if you don’t want to, you do it, that’s another form of expression. Suzuki Seijun’s not really like this, but you do something precisely because you don’t want to do it. You dare to do it even though you’re not sure you should. That becomes a backdoor to expressing yourself.

Sasaki: I understand what you’re saying, about how self-expression is possible in any situation. Especially about skillfully turning those conditions to your advantage. But an artist (sakka) doesn’t want to have to go hunt for themselves inside material assigned to them by someone else. They want to sing songs that originate from inside themselves.

Hayashi: Yeah, that’s there. I think if you can do that, that’s great. But it’s precisely because the situation is not always like that, that is the reason why one wants to draw, why you want to express something. That’s what I think, it’s the reverse.

Sasaki: Someone got upset at me once when I said that it’d be better if Japan was like Vietnam. But in such a situation, you know exactly who your friends are and who your enemies are. Only what's essential remains. If you let everything be free, then the anxieties disappear and you end up having nothing to draw. (Laughs)

Hayashi: That’s true.

Sasaki: Taking a walk along a peaceful mountain path might be enjoyable, but it’s only when you suddenly get lost and nervous that you learn what you’re really made of. That’s when composure matters most.

What does Family and Nation Mean to You?

Hayashi: To me, everyone since the war thinks of themselves as victims. No one will say that they are a victimizer. You only hear people say that they are victims.

Sasaki: When you have a situation like in Vietnam, in a sense it becomes easier to act. Who is a friend and who is an enemy, what is wrong and what is right, become very clear in an objective sense. At that point, you have to choose which side you’re on. But like now when everything is tangled up, you can’t tell friend from foe, what’s real or what’s fake, what’s the truth or just a put-on.

Hayashi: But when the issue of beauty comes up, that becomes clear. Today’s Japan has no conception of “national beauty” (kokka bi), right? When beauty emerges, those conditions . . .

Sasaki: What do you mean by “national beauty”? Like, what makes the nation beautiful?

Hayashi: Say one specific thing is illuminated and reflects light, creating all sorts of shadows. You might try and attack the shadows, but it’s only an aspect of the actual thing. The nation, a lot of hope is being invested very consciously in it now, it’s being paraded around. I feel like the current situation is maybe like that.

Sasaki: But they won’t really parade it around.

Hayashi: They don’t have the aesthetic consciousness to do so.

Sasaki: But don’t they call this era “the season of politics”?

Hayashi: The “nation” (kokka) is written with characters for “country” and “household,” right? In the process of human growth, the household is an extremely important starting point, that’s what I think. There’s a French animated film called Le Roi et l'oiseau. And the end the castle is destroyed. I feel like that’s similar. But what do we personally think about the nation and the family? (Laughs) I’m not sure if I feel anything at all.

Sasaki: This might be the same as what you are saying, but inside me personally there’s nothing like the nation or the family. I’m not saying this to sound tough. They’re really just not there, even if they should be. When you try to spread your wings, that’s when you see that they [the nation and the family] actually do exist objectively, and they rope you in and bind you all up. They shouldn't exist any longer, but there they are. We shouldn’t have to think about the nation or the family anymore, but as I try to grow there they are restricting me.

Hayashi: I’m sure this depends a lot on the environment in which you were born and grew up, but in my case the existence of the family is actually really strong. . . . Ideas about urban planning are really interesting now, what they call the “megalopolis.” It's like they’re trying to take the country and design (dezain-ka) it as if it were a single castle. So place names mean nothing anymore. There’s just numbers now. It’s like the difference between flowers and ikebana. That’s when I think nationalistic thinking changes into a love that’s very different from maternal love. Today, culture has become highly centralized, but regional culture still exists, with its own notions of “family” and “soil” (dojō, “homeland”). What’s happening now is not like what Miyazawa Kenji did, going into the countryside and making it shine. The light source itself is being cut out at the root.

Sasaki: Do you mean that once it’s cut out at the root then something personal and individual will sprout in its place?

Hayashi: No, I think the soil for something to sprout will always be there. What I mean is that, culture today is spreading out from the center. That’s having an effect and it’s creating tensions.

Sasaki: Everything becomes uniform.

Hayashi: Light from the center is being projected outward and that erases roots. That’s why I think nationalism can’t grow. People need to look more closely at their own place in the world and refuse the light from the center.

Sasaki: There’s a line in a Tanikawa Gan poem that goes, “Do not go to Tokyo, instead create your own hometown (furusato).”

Hayashi: I was born and raised in Tokyo, so everything is too easy. But there’s also an unhappy side to that.

Sasaki: I live in Kobe. There’s no anchor that Kobe is tied to. The idea of distinctive Kobe culture or regionalism is really weak. Strictly speaking, you probably can’t called Kobe “regional” (chihō).

Hayashi: Do you think that’s because of geography?

Sasaki: Yeah, geography, that probably has a lot to do with it. There are a lot of immigrants (nagaremono, “drifters”) in Kobe, and very few people whose ancestors have been living there for generations. For the most part, people from Kyushu or further south like Amami Ōshima don’t come all the way to Tokyo, they end up finding work in Osaka or Kobe, stay there for awhile, and then move to somewhere else. That’s why we don’t discriminate against outsiders. So it [regional identity] doesn’t develop. Things are fluid. People steal away on ships from Korea. People come looking for work even from Okinawa. Time passes and they drift away. So in Kobe, there’s nothing that’s distinctive only to the region.

Living in the 1960s

Sasaki: There’s certainly the question of generation. People involved in the student movement in Tokyo, it’s not that their theories are the same as those of students in Europe, but a shared sensibility allows them to communicate with one another. A 60s feeling of living in the same age, I think that is increasingly expanding.

Hayashi: I don’t pay much attention to what’s going on outside. I shut myself in.

Sasaki: When I show my “A Dream in Heaven” to hippies, they say they get it. And I get that they get it. I get them way more than I get Japanese who say they don’t get it at all. Of course that makes me happy.

Hayashi: I have nothing like that. I assume there’s no way anyone will get my work.

Sasaki: I think that too.

Hayashi: There’s a lot in common between me and Sasaki due to the fact that we belong to the same generation. But you’d never know that just looking at what’s going on immediately around us. When we make statements, there’s a huge difference between us, that’s what I feel sometimes. Because we are in the same circumstances, we gravitate toward very similar things. But we don’t have anything that we are really committed to. It’s like we just float along.

Sasaki: So, I like Oe Kenzaburō’s novels. Sometimes these delinquent youths appear in them. They really appeal to me. I think if I were to meet someone like that, I’d definitely become his friend.

The Energy of the Beatles

Hayashi: I get really bored watching movies with logical plots that don’t know which way to go. It’s better to have a nothing story with things suddenly happening. For example, I think the Beatles’ movies are really great. “Yeah yeah yeah,” really punchy, lots of energy. Then they suddenly switch into song. No matter how you edit shots or try to express something in words, you’ll never be able to reproduce that kind of transition. It has incredible power.

Sasaki: The first time I saw a Beatles film, I was so happy that I cried. There’s no logic to it, and it’s not just sentimentality, but tears come to my eyes. Cry cry baby, they’re that sort of movie. To try praising that kind of movie through some theory would be pointless. Let’s take these four youths and let them free in some crusty medieval English town and see what happens, you can say things like that though. That scene where they’re in the freight train and sit on buckets and sing, I like that scene so much it made me cry. Also where George Harrison walks by wearing a funny hat, and when they do meaningless things in the park.

Hayashi: That bird’s eye view scene?

Sasaki: Loved it.

Hayashi: There’s a scene like this also in Help!, where the audience screams and “participates” in the scene. In kabuki people will yell out “Narikomaya!” [the name of a family of actors], but it would be interesting if they did something like that in a Beatles film. [Translator’s note: Hayashi seems to be confusing Help! with A Hard Day’s Night]

Sasaki: When you get to like “Revolution” or Revolver, god has arrived and I just can’t get into it anymore. The initial energy they had has like evaporated on the frontier of enlightenment or something. I still wish they could find a way to keep that really dark energy going . . .

Hayashi: Forget it.

Sasaki: That’s why they needed Rhythm and Blues or some other method to work it off. See, I think the Beatle’s energy was nihilistic. They don’t put value in anything. Ono Jūzaburō wrote about this in one of his poetry treatises, that a nihilism that sees god is boring, that nothing is worse than a nihilism that turns into optimism through enlightenment. Not letting a frustrated nihilism be dissipated by turning it into a spectacle, holding out against that is what’s important.

Hayashi: You’re saying that’s why their early period is good?

Sasaki: Yes, all of it.

Hayashi: I don’t really feel that way, about the nihilism or anything. If it’s good, that’s enough. (Laughs)

Sasaki: Well, yeah, that’s true.

Hayashi: I don’t get the feeling that the Beatles are enlightened.

Sasaki: But they’re no longer the spokesmen of youth.

Hayashi: Really? I don’t know. I don’t think any one person or group can be the spokesperson. You can’t say that’s all that the four of them are, you can’t just take one group. Then again, I think they do speak for some part of what’s going on now, so I can’t say they don’t speak for anything. (Laughs)

Sasaki: No, but see, there was a time when the Beatles’ music represented that entirety of a certain generation living simultaneously around the world. It functioned as the music of youth. Otherwise, there’s no way they could have become so popular.

Hayashi: Hmmm.

Sasaki: I think everyone says this, but it’s not just that they made great music, but there’s something about them that everyone could connect with. Sure, there’s still music aficionados who think that what they do is good.

Enka, Children’s Song, War Songs

Hayashi: So what do you think about enka?

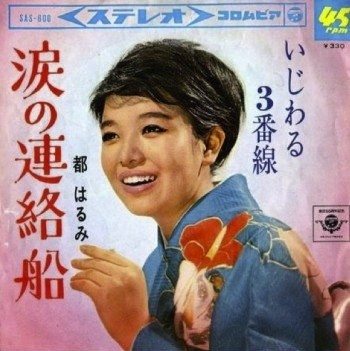

Sasaki: I like Miyako Harumi and Kitajima Saburō. I like that cookie cutter-type enka.

Hayashi: You mean their early stuff?

Sasaki: Miyako Harumi’s recent stuff is no good, but I like Ferry of Tears (Namida no renrakubune). Kitajima Saburō’s Brother Loyalty (Kyōdai jingi) and Ship of Tears (Namida bune). I like enka that is stereotyped through and through.

Hayashi: For me, it’s not individual singers that I like, but songs.

Sasaki: Me too. There’s plenty of Miyako Harumi songs I don’t like.

Hayashi: I like Overflowing Petals (Kobore bana, by Ishihara Yūjirō). I also like Suizenji Kiyoko, for example her The Crying Migrating Bird (Namida o daita wataridori).

Sasaki: Dime a dozen, aren’t they? (Laughs)

Hayashi: In Taishō era songs, flowers don’t bloom. Like, “the pampas grass that doesn’t flower” [line from Boatman’s Ditty (Sentō kouta, 1921-23)]. But in Overflowing Petals, they’re flowering, and then they fall, and then they become seeds. (Laughs) In a song like Lieutenant Ogawa’s Song (Ogawa shōi no uta, 1898), there’s “the flowers of the cherry tree do not blossom, they fall without waiting for spring . . . my body is penetrated by the beating waves, and becomes the seed of tears.” But when it comes to old songs, children’s songs (dōyō) are really amazing. Like, “when was it that I saw it alight?” and “it sits there still on the end of the clothes pole” [lines from Red Dragonfly, 1927, referring to a nanny that has gone away]. During the Sunagawa protests [against the expansion of the US military’s Tachikawa Airfield in the late 50s], I don’t which side it was, but someone started singing Red Dragonfly. I find that fascinating.

Sasaki: There really are some amazing lullabies (komori-uta).

Hayashi: Yeah, and some really scary ones.

Sasaki: They express a frustrated energy. Enka is ultimately the same, the emotions don’t have an outlet. Terayama Shūji or someone said that what’s distinctive about enka is that it can’t be sung as a chorus. They have to be sung as if one was isolated and helpless.

Hayashi: In military songs, there’s Umi yukaba (If I Go Away to the Sea, 1937, a famous kamikaze song). When I hear that, I always remember this one movie scene. The submarine I-1 is unable to surface and sinks, then Umi yukaba plays. It’s not that the song flows over everyone, but strikes each and every person to the heart, with a lot more energy than any war march. I don't know how it is in other countries (laughs), but in Japan we like burying things inside us. And the deeper we bury them, the more horrible they become. It’s like folding a crane or folding origami in general, everything is folded into itself, nothing spreads outward.

Sasaki: Right, inward and inward. Hard feelings get all sticky and indirect, enka is like that. The Hour of the Ox (Ushi no toki mairi) is like that too [a Shinto ritual in which a scorned woman sets a curse upon her enemy]. War songs, though, I don’t think they are having the effect on us that they are supposed to.

Hayashi: Like Comrade-in-Arms (Sen’yū, 1905). It’s all stiff. [The song, set in Manchuria, is about the experience of having fellow soldiers die beside you.]

Sasaki: That’s an anti-war song to me. It’s like When Johnny Comes Marching Home, which was originally an anti-war song. Johnny returns from war having lost his limbs.

Hayashi: That song is incredibly depressing.

Sasaki: Everyone shows up with tears in their eyes. But then it was turned into a war song for brave soldiers of the South, and then back again into an anti-war folk song. When Japanese of the war generation sing war songs, it’s to confirm their shared experiences. But does that make them feel happy? Does it make them feel sad? They look they’re having fun, but I imagine they actually feel extremely sad.

Hayashi: . . . .

Sasaki: The melody of We Shall Never Forgive the Atomic Bombings (Genbaku o yurusumaji, 1953), that’s an elegy. It doesn’t express any anger. To put it bluntly, it’s a song of defeat. Only the lyrics are brave. However, the May Day song is based on a war song, The Hanging Cherry Branch (Banda no sakura, a reference to the song The Infantryman’s Mettle [Hohei no honryō, 1911]). First it was turned into a school song (ryōka) and then into the May Day song after the war. Only the lyrics changed.

Hayashi: The melody stayed the same?

Sasaki: The same.

Hayashi: I guess melodies are what survive. Wiser to write music I guess. (Laughs) But I like lyrics better. They can be sung to a melody at any time.

Should We Expect Much from You in the Future?

Sasaki: What a topic! The only way to answer is to describe what we actually want to do. I pass! (Laughs)

Hayashi: It’s not like I feel combative about what people say. I don’t really think much about readers.

Sasaki: You shouldn’t only think about it as a person starting off as a child and then becoming an adult. It’s possible for both to happen at the same time. Oshima Nagisa once said that it’s not possible to access the masses only by singing the song that is inside oneself. That’s what his early works are like, anyway. One can’t just take a company’s directives as is, but like Hayashi said earlier, you have to create while discovering yourself within those conditions.

Hayashi: That sounds nice, but I think Oshima is only saying that now that he’s out of material. (Laughs) But when someone is able to pow! express something even when the entire thing is decided beforehand, that’s powerful. Like Suzuki Seijun. You don’t go to the theatre expecting to see that, and that’s what makes it powerful.

Sasaki: Oshima Nagisa took a stand right from the beginning, so that’s why what he’s doing now is disappointing. Even with TV commercials, sometimes you see things that are really striking. It’s precisely because you watch it as just a mere commercial that a certain shot strikes you as really fresh. With things they call avant-garde or hard-to-understand, the audience is used to looking at them in a patterned way. When you go see plain old erotic films or samurai films, it’s a real shock when a striking shot occurs.

Hayashi: Like a chink in the armor, so to speak. (Laughs)

Sasaki: Like you’ve been caught off guard. (Laughs) The shock of being suddenly slapped in the face is really big.

Hayashi: It’s no fun going to see so-and-so’s whatever, expecting something, and then being disappointed if it doesn’t happen. It’s better when you don’t have any expectations.

Sasaki: But it’s also boring if your expectations are met. (Laughs)

Hayashi: Does that ever really happen? If you are actually expecting something, I don’t think it ever goes that way. But ultimately what is “expectation”? You go with expectations, the thing ends, and your left still expecting something. (Laughs) So like how about with this conversation, if we suddenly switched to a commercial? That would be surprising. (Laughs)