As copies of Sasaki Maki’s Ding Dong Circus and Other Stories, 1967-1973 trickle out into the world, Breakdown Press and I are finishing the next volume in the series, Hayashi Seiichi’s Red Red Rock and Other Stories, 1967-1970.

Like the Matsumoto Masahiko and Sasaki Maki books, Red Red Rock is kindly sponsored by the Sainsbury Institute for the Study of Japanese Arts and Cultures in Norwich, England. Over 200 pages, it collects most of the rest of Hayashi’s work from the late 60s (thirteen works, all but two from Garo), from his earliest Pop-influenced allegories about postwar Japanese identity in light of the Vietnam War to the experimental homages he made to the Nikkatsu universe just prior to commencing Red Colored Elegy (1970). It also includes a lengthy essay by me (written while on a Hakuho Foundation Japanese Research Fellowship) trying to make sense and order out of an eclectic and deeply culturally embedded body of work, placing Hayashi’s experiments in relationship to the contemporary avant-garde art scene in Tokyo.

It’s obviously appropriate that Sasaki and Hayashi books should follow one upon the other, since the two artists were the original representatives of Garo as house of avant-manga. Their work provided the magazine an incredible balance. Shirato Sanpei’s old school leftwing epic of peasant resistance, The Legend of Kamuy, held down the first 40-100 pages of most issues. Filling out the middle was a neo-kashihon gekiga tribe of idiosyncratic talents, including Mizuki Shigeru’s yokai parables and further adventures of Kitaro, Tsuge Yoshiharu’s mystery-cum-travel tales, Tsurita Kuniko’s off-kilter stories about youth and counterculture, and Tsuge Tadao’s anti-cathartic portraits of urban working life. When it came to Sasaki and Hayashi, some people weren’t sure whether their work should be called manga. Their work introduced cutting-edge Pop and avant-garde sensibilities into the comics medium, and created bridges between manga and the wider artistic counterculture of late 60s Japan.

That might have been all that their work had in common. Nonetheless, in the late 60s “Hayashi and Sasaki” became a set conjunction, and has remained so in much retrospective writing, even for writers who recognize that the main thing they shared was their difference from everything else. Amongst the standby names used to group their work were “avant-garde manga” (zen’ei manga), “difficult-to-understand manga” (nankai manga), and “anti-manga” (anchi manga). Applied with more thought was “eizō manga” (image manga). Its English equivalent of “imeeji manga” was also often used, though in many such cases “image” signified nothing more than the opposite of “words” (kotoba), not unlike in the “image and text” couplet favored in North American academic comics theory. In more imaginative applications, “image manga” and especially “eizō manga” meant comics that were better comprehended through an aesthetic appreciation of individual images and the poetic correspondences between one image and the next, rather than through the conventional frameworks of caricature, story, humor, or allegory. It also signified comics in conversation with other image-based media, and particularly technologically mediated media like film, television, and photography.

As a concept originating in film theory (particularly Matsumoto Toshio) and media studies (translations of Daniel Boorstin and Marshall McLuhan), eizō also performed an important discursive function for manga criticism – or at least, it could have. In the 60s, writing about manga was (as it is largely still today) defined by either social and historical contextualization (theories of audience formation and allegorical readings vis a vis contemporary sociopolitical events) or a formalist historiography relating new developments to prior examples within the history of manga itself. What eizō offered was a manga discourse beyond medium specificity, beyond the context of manga markets and manga readers, and out in the wider field of experimental image-making in the 60s. Sadly, this never bore fruit. What the archive holds instead is a smattering of forgotten articles by college students and professional art and manga critics on the subject of “image” manga, whose lack of long-term impact can be seen today in the singular focus on “cinematic techniques,” and the occasional retro-minded forays into illustration and kamishibai. This despite the fact that manga in the 60s had rich and complicated interactions with the “new media” of television and expanded cinema, and with photography and graphic design.

Speaking of graphic design . . . in the coming months, I will be looking more closely at “eizō manga” as a theory and practice, with the caveat that understanding the links between manga and 60s “image culture,” and by extension the manifestation of artists like Hayashi and Sasaki, requires paying attention to the mediating force of graphic design, the power and scope of which grew rapidly in the mid 60s around figures like Yokoo Tadanori, the emergence of full-scale art direction in magazines, and collaborations between designers and the “underground” theatre movement. Ōtomo Shōji’s role in the transformation of Shōnen Magazine into a so-called “paper television” is perhaps the closest parallel in manga publishing (and it’s not very close), while Sasaki and Hayashi show that “image culture” and the “graphic design turn” also melded productively in the work of individual artists.

For example, Sasaki’s way of drawing figures and buildings is inexplicable within a medium-specific, shōnen-shōjo-gekiga (“story manga”) trajectory of style, but makes perfect sense if you are aware of what was loosely grouped as “nonsense” illustration in the late 50s and 60s (which belonged to the world of design more than that of “manga” as we know it today, and which was better appreciated by art critics than Tezuka fans, and which defined “avant-garde manga” until Sasaki and Hayashi came along). Likewise, Sasaki’s non-narrative panel sequences seem a lot less jarring if you approach them with an “open eye,” forgetting about conventional reading order and letting your eyes be guided instead by the gravitational pull of the overall page composition, as you would a painting or poster.

As for Hayashi, the links to design are more explicit. Before joining Tōei in 1962, he attended a small design school in Yoyogi, where he was trained in the clean, functional modernism of the International Style. The continuing influence of this training I think can be seen in the careful and stark balance of positive and negative, the geometric division of space, and the planar flattening of architecture in works like “Flower Falling Town” (October 1968), “Red Enamel Shoes” (June 1969), and Red Colored Elegy. What’s interesting about this is that Hayashi’s other major influence from the design sphere was, I think, Yokoo Tadanori, who abhorred the cold functionalism of high modernism. Hayashi struck a successful compromise between the two, borrowing specific motifs and compositional ideas from Yokoo’s eye-popping, iconographically retro posters, while steering clear (in most cases) of Yokoo’s visual mash-ups in favor of more structure and historical attention.

More generally, there is a poster-ish quality to many pages of Hayashi’s manga, often underwritten by an interpretation of typography and layout through (not only traditional sound effects, but) song and the visual culture of music (a natural line of thinking in an age when theatre posters and album covers were foci of new developments in design). On a grander scale, Red Colored Elegy, with its many graphic references to film, animation, television, illustration, posters, et cetera, might be seen as the culmination of something lurking in Hayashi’s shorter works prior, which is rethinking manga visual narrative in terms akin to all-and-sundry “magazine” art direction. The Japanese for magazine, “zasshi” (literally “miscellaneous publication”), implies the same thing. Gesturing in a similar direction, art and manga critic Ishiko Junzō proposed the name “narrative illustration” (he uses the English) for Hayashi’s experimental manga form.

Graphic design, however, was generally not how observers in the 60s understood the emergence of the Hayashi-and-Sasaki “image manga” phenomenon. This is a complicated topic, like I said, so I’ll just give you a taste of contemporary discourse, first through the writings of a leading critic, then through a mass circulation magazine. This way you’ll get to see both the intellectual and the vulgar period receptions of Hayashi and Sasaki’s work.

First, the intellectual.

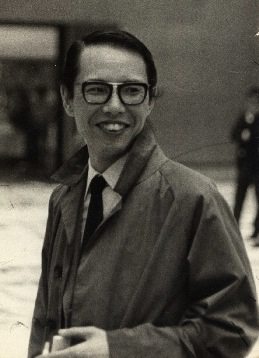

In 1970, the same Ishiko Junzō (1928-77) as above wrote a brief synopsis of gekiga for the architecture and design magazine SD. It isn’t one of Ishiko’s best pieces – it is basically a compacted version of arguments made in the co-authored classic, Contemporary Manga Theory (Gendai manga ronshū, Seirindō, 1969) – but it suffices for my rambling purposes here. Ishiko begins by recounting kashihon gekiga’s relationship to everyday urban experiences in postwar Tokyo. He explains how this evolved through Mizuki Shigeru’s and Tsuge Yoshiharu’s late kashihon and Garo work. Then Ishiko turns to Hayashi and Sasaki, with the disclaimer that “it might be inappropriate to call their work gekiga.” He offers instead “anti-manga” as a rubric (I don’t think this term was his invention). Note that “image manga” in Ishiko’s scheme is functionally post-gekiga: it marked the end of manga as visual storytelling and the end of the drawn image in manga as a representation (via depiction) and index (via expressive facture) of postwar experience. Key to this paradigm shift, according to Ishiko, was how Hayashi and Sasaki broke with the traditional economy of “images and language” in manga.

“If Hayashi is based on feeling (kansei), Sasaki is far more based on perception (kankaku),” writes Ishiko. What is the core of Hayashi’s feeling-based manga? Ishiko uses the example of Hayashi’s frequent use of lyrics from kayōkyoku. That is, lyrics not from just any music, but a variety of popular song often read as “Japanese” and dominated by sentiments of romantic heartbreak, loneliness, and desperation. Since the life of lyrics, explains Ishiko, depends on their activation through rhythm and melody, and their being channeled through a singer’s palpitating body and voice, to write lyrics out as text is a recipe for killing them. Not only does Hayashi write out lyrics, he also couples them with “very flat and diagrammatic” images of flowers and girls, thus emphasizing “the feeling of unsubstantial-ness” (hi-jittaikan). But now the twist, the secret to Hayashi’s success: “Hayashi tries to fabricate palpable life by reviving lyrics” through a process in which “the act of seeing” itself “gives flesh” by corresponding to patterns of thinking and living in everyday life.

This is obscure even for Ishiko, whose writing often feels off-the-cuff. What I think he is trying to say is that by employing motifs (flowers, women, Japanese landscape) and popular song lyrics that the average person can recognize and identify with, Hayashi has found a way to use disembodied and schematic styles of image and text to achieve just the opposite, something highly moving and emotional. I suspect what Ishiko is driving at is the power of abstraction to incite the imagination and emotions more effectively than overly naturalistic and detailed representations (a la gekiga), but only when abstraction is coupled with popular sensibility and mass appeal (also a facet of gekiga in Ishiko’s understanding). Perhaps Hayashi’s manga stood in relationship to gekiga, for Ishiko, in the way that the nouvelle vague stood in relationship to genre film, a relationship that Hayashi explicitly explored in his Godard- and Suzuki Seijun-inspired works from late 1968 to 1970.

Now Sasaki. What is the essence of his perception-based manga? Since the analysis of Sasaki’s work in the SD article is pitifully thin, let me move instead to Ishiko’s chapter on the artist in Contemporary Manga Theory, titled “The Image Event” (Imeeji no ivento). Though he doesn’t state this outright in the text, Ishiko clearly regards Sasaki’s work as an opportunity to plug manga into contemporary art discourse and media theory. Ishiko, mind you, was trained as an art historian and was simultaneously active as one of Japan’s top art critics. One of the major themes of art discourse at the time was “intermedia,” and so Sasaki’s “image manga” belongs to a wider trend of artists breaking with the modernist allegiance to medium specificity. “It is hard to say that Sasaki’s work is manga,” writes Ishiko. At the same time, “it is hard to say that it isn’t manga.” It is this “generic affirmation through double negation” (“it’s not possible to say that it’s not manga”) that makes Sasaki’s practice (alone amongst manga artists) comparable to contemporary avant-garde art. Key to this, according to Ishiko, is how Sasaki rethinks the nature of the image in manga and by extension the relationship between word and image.

While most critics (myself included) would probably be inclined to write off the “difficult-to-understand” label as philistine laziness, Ishiko wisely (in an era when manga criticism was fighting for a readership) makes it a central part of his explanation. Ishiko posits, with reference to contemporary media theory, that the popular reception of Sasaki’s manga as “incomprehensible” is premised on expectations of manga as a vehicle for communication. Instead, “Sasaki’s work asks us to comprehend incomprehensibility itself,” not unlike how one approaches abstract and surrealist art. As with modern art, Ishiko explains, it is necessary not to see images in Sasaki’s work as representations of how things are in the real world or as symbols for abstract ideas. The first principle of Sasaki’s art is “the image itself,” the image divorced from communication and thus unmediated by language. So far, this probably sounds to you like a “What is Modern Art?” primer. For manga discourse at the time, even that was progress.

Ishiko’s text gets more interesting when he tries to align his art history training with contemporary media theory. For Ishiko, the “image itself” principle of Sasaki’s work is not some esoteric modernist experiment. It is rather a practice reflective of the “age of image events” proposed by Daniel Boorstin, in which, thanks most of all to the power of “pseudo-events” on television, images have achieved an “independent actuality” (Ishiko) versus their traditional function as language-like vehicles of communication. One comes to experience the image itself directly as a body of non-referential “information,” rather than as a proxy for an event happening in some other place or at some other time. Likewise, Sasaki’s uses the manga page and magazine envelope not as a “medium” in the traditional sense, but as a “site” for experiencing the image as image in the “here and now.” If his work appears to most readers as incomprehensible, that is only because most readers are mistakenly looking for meaning behind the “image event” of Sasaki’s manga pages. In fact, contrary to complaints of esotericism and opacity, precisely because Sasaki’s work does not harbor codes, it is “more open and public” (kaihōteki, ippanteki) than traditional forms of manga. If taken to its conclusion, Sasaki’s image manga – being “neither manga nor illustration nor design, but an inclusive manifestation of the image” that encompasses those fields and more – becomes anonymous and collective, indistinguishable from the wider culture of the image.

Though marching out from Boorstin, who had nothing good to say about the “image event,” Ishiko’s reading seems to get lost along the way in McLuhan’s global village. Ishiko goes on to describe in general terms the shrinking of modern individualism and privacy amidst the growing mass media machine. But overall, his appraisal of Sasaki’s “image events” is positive, which is understandable given Ishiko’s formalism and placement of Sasaki’s work in an artistic avant-garde trajectory, but perverse from a critical theory perspective (which is implied in citing Boorstin) because he ignores those features of Sasaki’s work that indicate critical intent.

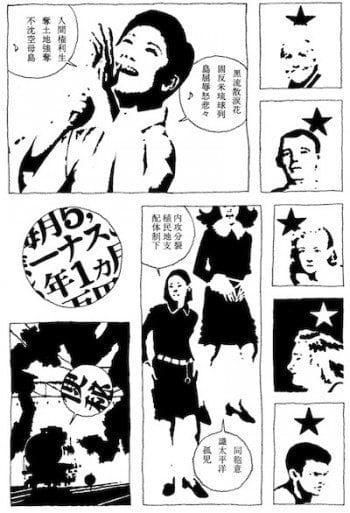

In Contemporary Manga Theory, Ishiko does not even bother to describe the referents of Sasaki’s images. His only concrete example in modern art comes from painting: a burning giraffe in a desert. He is presumably referring to Salvador Dali’s painting of 1937. In the abridged SD version of his thesis, Ishiko sums up Sasaki’s iconography as “elephants, people, and cups,” which is disingenuously bland. Why not “barbed wire, guns, knives, and crumbling and burning buildings,” since those are what really stand out? Even if one doesn’t know that the burning giraffe in Dali’s universe is an omen of war, doesn’t it inevitably read as violent and foreboding? In a slightly earlier text (from late 1968), Ishiko looks at a recently published work by Sasaki (untitled, December 1969) and identifies “Kennedy and Katsu Shintarō, an astronaut, also baseball and boxing, scenes of war and love, and other miscellaneous images pulled in from the mass media.” But then only comments on the black and white tonal contrasts of Sasaki’s traced photograph method and the “seeming random montage of empty-shell images.”

Contrary to Ishiko’s “images as images” thesis, the recurrence of thematically related motifs in individual works indicates at least a mildly allegorical intention on Sasaki’s part. And since many of these motifs have a topical and political edge to them (and usually one implying violence), even if Sasaki was not trying to “communicate” a verbally-reducible message through his images, he certainly thought of his images as vehicles for inducing heightened states of emotion, oscillating between joy and fear. While his earliest “anti-manga” from 1967 and early 1968 do indeed emphasize the graphics of drawing itself and the joy of disparate iconographical juxtapositions (this is where Ishiko’s formalist reading makes some sense), already overarching tropes of murder, oppression, and alienation are readily apparent. Amateur critics pointed out as much in Garo’s reader’s column and in university newspapers. From the beginning, Sasaki’s “image events” had what one might call a “subliminal narrativity” that emerges through the repetition of human characters, pregnant objects, and emotive expressions within a visual field otherwise dominated by graphic and iconographical excess.

By late 1968, the worsening situation around the Vietnam War and conflicts in Japanese cities between students, anti-war protestors, and police had clearly disturbed Sasaki. The marked increase in his work of images of violence, pain, and war, and the frequent incorporation of traced photographs, together express a concern with the relationships between the mass media “image event” and social oppression. I am not sure how aware Sasaki was of contemporary experimental cinema, but this feature of his work begs for comparison with the collage-based, multi-screen projections of Matsumoto Toshio (particularly “For My Crushed Right Eye,” 1968) and similar endeavors in flicker-based and expanded cinema. That field, after all, was the home turf of “eizō” in contemporary discourse (see Yuriko Furuhata's book, Cinema of Actuality: Japanese Avant-Garde Filmmaking in the Season of Image Politics, 2013). Even in Sasaki’s most entropic works, like “Sad Max” (February 1969), the “subliminal narrativity” continues to assert itself through the pulsing repetition of a young man’s face, which I take to be a cipher (Paul Sharits-style) of a single perceiving subject on whose consciousness the surrounding visual chaos is mapped. Sasaki might have abandoned the organizing principle of “story” in manga, but avant-garde art, filmmaking, and design offered artists and viewers other ways to organize images coherently.

How could Ishiko, with his background in art history and familiarity with the contemporary art scene in Tokyo, fail to see anything but images-for-image’s sake in Sasaki’s work? How could he, especially after something like “The Vietnam Debate” (January 1969), which lays its moral outrage over the mass media and consumer society out on the table, ignore the critical dimension of Sasaki’s practice with regards to contemporary “image culture”? Sasaki was more Boorstin-ian, and more surrealist I think (in the psycho-symbolical sense), than Ishiko’s formalism makes him out to be. But given continuing suspicion of iconographic readings within the discourse on avant-garde manga, I imagine discussion of Sasaki’s manga will at some point have to pass through the kind of debate that divides art historians over Robert Rauschenberg’s work – is it allegorical? is an allegorical reading vulgar reduction? is it media critique? is a critical media theory reading armchair intellectual fantasy?

Now let’s turn to the middlebrow version of “image manga.” While Hayashi and Sasaki were breaking down walls inside manga, the outside world was eagerly consuming counterculture as a commodity.

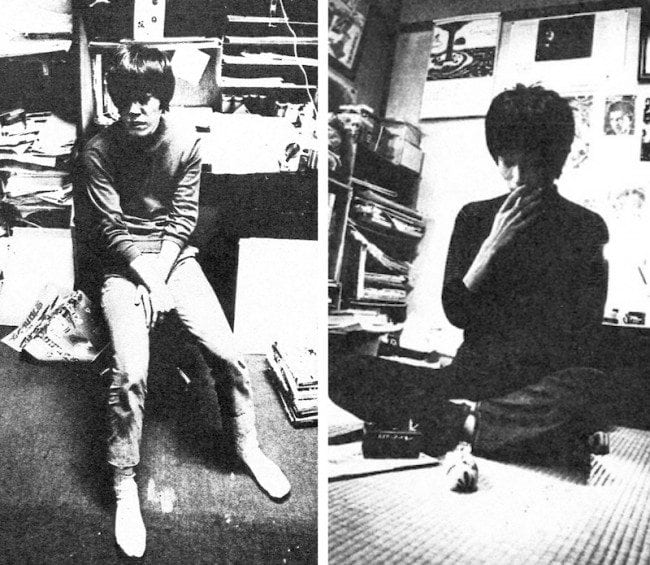

In August 1969, as part of its regular coverage of the Tokyo’s youth counterculture, Weekly Asahi (Shūkan Asahi) published a short piece titled “A Vogue for I Don’t Get It” (“Wakaranai no ga ryūkō suru”), featuring three artists who drew for Garo. The last of the three, Fujisawa Mitsuo, who specialized in surrealistic, metamorphic stories, is all but forgotten today. At the time, his work would have been labeled “nonsense” or (for their non-erotic obsession with genitalia and penetration) “harenchi,” a youth buzzword meaning “shameless” or “lewd” in a playful way. Sasaki Maki, with his non-narrative collage-like layouts, led the article as the epitome of incomprehensibility in manga. Between the two, presumably as an artist who maintained a balance between surrealism and dada, was Hayashi Seiichi.

Hayashi claims that “A Vogue for I Don’t Get It” enabled him to quit his day job as an animator. He had been working at KnacK, a small studio (founded by former Tōei stalwart Tsukioka Sadao) specializing in animated segments for television programs. Hayashi had already been getting media attention because of his work for Garo, though mainly from campus newspapers and coterie journals. The Weekly Asahi feature brought TV appearances, additional mass print magazine coverage, and, more importantly, artistic commissions from monied clients. Red Colored Elegy was begun soon after obtaining said freedom. I have not asked Sasaki his opinions about the essay, but it comes two months after he had begun a year of weekly four-page comics (if they can be called "comics") for Asahi Journal, a popular news magazine widely read by students and intellectuals. The only time Sasaki lived in Tokyo was while he was drawing for Asahi Journal, which paid well. Presumably, since Weekly Asahi and Asahi Journal were published by the same company, “A Vogue for I Don’t Get It” was, at some level, designed to promote Sasaki’s serial.

Whatever the case, “A Vogue for I Don’t Get It” was important for both of the artists’ professional careers. However, as a work of manga journalism or theory, it will definitely not blow your mind. I have translated most of the feature’s texts (minus Fujisawa’s blurb) below. That a high-circulation, news magazine was covering Garo and experimental manga (however superficially) was really not so bizarre. Since the mid 60s, magazines had been reporting on the phenomenon of university students reading manga, when they should have been reading Dostoevsky and Sartre. It was one facet of how disturbingly different were baby boomer values from those of people who lived through the war. Once the late 60s came, and youth culture turned more exotic, magazines barely tried to hide their voyeurism. In the months leading up to this manga article, for example, Weekly Asahi committed numerous articles (with multi-page photographic spreads) to the gamut of youth culture and artistic goings-on in Tokyo, organized around buzzwords like “harenchi,” “saike” (short for the English “psychedelic”), and the all-encompassing “angura” (underground), of which Shinjuku was the undisputed “mecca.” Whatever critical dimension intellectuals and historians might perceive in Hayashi and Sasaki’s work, that was of no interest to Weekly Asahi. Avant-garde manga was essentially no different than psychedelic posters, happenings in the street, and go-go dancing inside film projections. If this article were given a subtitle, it might have been something like “weird manga in the age of expanded consciousness and youth revolt,” or more simply “angura manga.”

“A Vogue for I Don't Get It,” Weekly Asahi (August 22, 1969)

Comics are booming. Amidst the uprising of salaryman comics, nonsense things, and gekiga, did you know that there is also a comics faction that commands the crazed support of young readers, especially college students? The support of these so-called fans is so great that they say they want to put these artists’ work in their pocket before they smash their way through the riot police.

As you can see, these kinds of comics are a way far out from what we usually think about comics. Though a lot people say they simply don't get it, there’s no doubt that what we are seeing is a “new phenomenon” in which comics have left the world of stories and entered that of the image (imeeji). Young people don’t like having things explained to them. They say it’s up to the reader how they want to feel about a manga. They say they understand through the senses, through the skin, and immerse themselves in this new breed of comics that way.

From amongst the artists of “incomprehensible manga,” here we introduce the work and corresponding manga theory of three artists: Sasaki Maki, Hayashi Seiichi, and Fujisawa Mitsuo.

Sasaki Maki. Born October 18, 1946 in Kobe.

To me, maybe manga is “an operation to reveal the me that even I wasn’t aware of.” What’s really surprising to me is when people say that my work is “hard to understand” or “difficult,” since I think I’m drawing things that are really easy to understand. I am not a special or different kind of person. I am just another young person living in the same environment and same circumstances as everyone else.

However, I don’t think there would be any point for me to start drawing obvious things now. I want to make work in which the viewer also participates, mobilizing his or her own imagination, knowledge, and opinions. Today, whether it’s TV dramas or novels or manga, everything is over-explained. I don’t feel like watching or reading those kinds of things. As a viewer, if something can be understood just by staring dumbly at it, that’s insulting. Or telling someone else what to think, that’s arrogant. “Who do you think’s going to listen to you?” That’s what I want to say in response to such arrogance.

Anyway, who decided that manga had to be made up of panels and explanatory text? Why should we be expected to honor a decision made by someone we don’t even know? We should go ahead and destroy that, that’s what I think.

Hayashi Seiichi. Born March 7, 1945 in Mukden.

I think it was about two years ago. After a certain television director learned that he was fired, I heard that he left the room whistling Nishida Sachiko’s “It Was All But a Dream.” For me too, there are days when I wake up in the morning and start singing a tune for no reason. But it fits the moment exactly. Once I became aware of that, that's when I started thinking that I wanted to draw manga that matches up perfectly with phrases from kayōkyoku [roughly, enka].

There’s nothing difficult about manga. If it’s interesting, that’s good enough, that’s what I think. I don’t stress too much about it. I want to be able to think, “well this is interesting,” and draw what I want to say with ease.

There should be manga like Sazae-san that appeal to a wide audience, and there should be manga that require one to be a teenager to understand. I can’t claim a long or diverse life experience, so there’s no question of me being able to create comics that everyone can understand. But, I think it’s the same for college students today, everyday life feels super bottled-up. We might think that we want to do something, but it’s frustrating because there’s nothing we can do about it. So I draw comics. It’s through that shared sympathy that other young people can understand my work. When people understand my work, it makes me really happy.

Some closing comments.

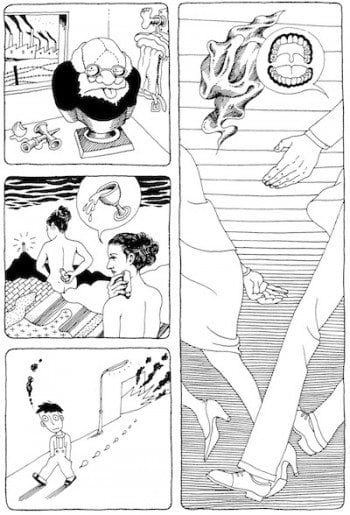

The two manga pages reproduced above were included in the original article. Sasaki’s "A Giant Elephant" ("Kyōdai na zō," May 1969) shows a young man with his shirt open and carrying a short sword known in yakuza slang as a dosu – the image is presumably an homage to Takakura Ken – conversing with a ghost drawn in an inky, Inoue Yōsuke style, speaking in tongues inspired by the Beatles’ lyrics and Sasaki’s readings of Victorian nonsense verse. Hayashi was represented by a page from "Red Red Rock" ("Makkakka rokku"), which had just been published in the July 1969 issue of Garo. “When I saw the two of you having coffee and toast that morning,” recalls the elderly killer with the psychedelic glasses, as the pseudo-Elvis character stumbles away bloodied. As I explain in the essay for the Breakdown collection, this work is a good example of Hayashi’s influence from Yokoo Tadanori’s imagery and Suzuki Seiijun’s baroque reinterpretation of the kayō eiga (pop music movie) genre in films like Tokyo Drifter (1966). Perhaps by accident, Weekly Asahi has touched on an important and idiosyncratic feature of late 60s avant-garde culture, and that is the common use of yakuza as a ballast of stereotypes of traditional Japanese masculinity around which newfangled visual experiments could be conducted.

What bothers me about this article is not its reduction of avant-garde aesthetics to countercultural cool. Most readings of contemporary art could benefit from being tempered with consideration of how art fits into wider patterns of visual expression and experience. Instead, what strikes me as wrong is the political romanticism. The Weekly Asahi is being half flippant when it reports student radicals stuffing Garo into their pockets before waging war against the establishment. But I feel like it is precisely this kind of imagery that gives rise to what I was just talking about, the over-appraisal of avant-garde art and the massive confusion of political gestures in art and art writing with committed political action and expression. If you have any contact with recent English language writing on the Tokyo avant-garde, you will know that this confusion is endemic.

First of all, Hayashi and Sasaki themselves were openly nonpori (short for “non-political”). Both of them, in fact, stuck their noses up at campus politics and its modes of expression. In an interview I conducted with Hayashi in 2012, he recalled being invited with Sasaki to give talks at a number of universities in the late 60s, but being smart-asses they boycotted the proceedings by remaining silent for the duration. Similarly, Sasaki’s “The Vietnam Debate,” while primarily a critique of the moral indifference of Japan’s consumer culture to the current atrocities in the Vietnam War and their links with past atrocities during World War II, could also be read as making nonsense of the political discourse of the student left and its fellow travelers amongst the intelligentsia. When Sasaki Maki identified his ideal type of reader in period texts, he used the term “hippie,” which presumably meant the glue-sniffers and coffee house rats wasting away in Shinjuku. That scene had little invested in the anti-Vietnam protests and even less in campus politics. Perhaps, as Weekly Asahi suggests, some student radicals intuited Garo manga in ways that square adults could not. But I imagine most committed members of Zengakuren and Zenkyōtō would have seen only bourgeois decadence in the so-called “avant-gardism” of contemporary manga.

As for placing Hayashi and Sasaki’s work within the “expanded consciousness” of late 60s Shinjuku, this too has its limits. Sasaki lived in Kobe, and only very rarely made the trip to Tokyo. As I mentioned above, his only extended stay was for a year between mid 1969 and mid 1970, while drawing overtly “anti-manga” manga for Asahi Journal. The case is easier to make for Hayashi, who after all not only drank into the wee hours with the literati and hangers-on in Shinjuku, but also collaborated artistically with luminaries like Terayama Shūji, Kara Jūrō, and Wakamatsu Kōji. Yet he had a full-time job as an animator and a mother to support at home, so he wasn’t a full-time denizen of the scene. He smoked heavily, but only cigarettes. If there’s “expanded consciousness” to be found in his work, it is purely a trope, not a reflection of personal experience.

So what were Hayashi and Sasaki interested in? What did they think about the world of the 60s around them? One can make assumptions on the basis of their work, but happily Garo liked getting their artists to sit down and talk to one another as well as to critics and creators from other fields. Coming up next time: a full translation of a conversation between Hayashi and Sasaki published in Garo in 1969.