“Taniguchi Jirō shiron, dai-ikkai: Taniguchi Jirō to gekiga no jidai”

From The Taniguchi Jirō Collection 11: Kamigami no itadaki (Shūeisha, 2022)

Although Taniguchi Jirō passed away in 2017, his work continues to be of great interest in Japan, in Europe, and here in North America. Recently, Japan has witnessed a lushly beautiful repackaging of Taniguchi’s works bearing the English title "The Jiro Taniguchi Collection" (2021-present), reprinting many of the artist's most important works, some of which will be familiar to English-language readers, such as The Summit of the Gods, The Times of Botchan, The Walking Man and The Solitary Gourmet. This lavish edition (aizōban) is an investment in ensuring the continuance of Taniguchi’s legacy.

What is most remarkable about this series is that multiple publishers of Taniguchi’s works (including Shūeisha, Shōgakukan & Futabasha) came together to make the collection possible, with different publishers releasing different volumes. “I think this is probably the first attempt of its kind in Japan,” Natsume told us in a message. “It could only have been made possible by the fact that the author was Taniguchi Jirō, but since the publishers of the original magazine serializations were in charge, it could be a phenomenon unique to Japanese manga, which has developed mainly through magazine serialization.” Only Kōdansha’s Otomo: The Complete Works—a massive series begun last year, which will include Ōtomo Katsuhiro’s manga oeuvre and anime storyboards—comes close to matching the scope and quality of the Taniguchi series. European publisher of manga, Fanfare/Ponent Mon, for its part, is releasing a much-awaited English edition of The Solitary Gourmet later this year.

Natsume, as we know, has written about Taniguchi before. The first translation of Natsume’s work to appear on this site was that of a 2018 essay, “Time to Re-Evaluate Taniguchi Jirō’s Place in Manga”. The publishers of the new Taniguchi reprint project called on Natsume to do much the same for the supplemental essays included in those books. The essay below is the first of Natsume’s new five-part series on the artist, published on pgs. 2-5 of a supplemental insert to Shūeisha's debutante volume collecting The Summit of the Gods.

-Jon Holt & Teppei Fukuda

* * *

The lineage of Taniguchi Jirō’s works can be divided into two main parts, with his series The Times of Botchan (“Bōtchan” no jidai, 1987-1996) as a middle boundary zone. If one were to try to break things down even more, there are of course different ways to see his oeuvre, but I do not think anyone would disagree with me that The Times of Botchan was made during a pivotal period for the artist. When asked about The Walking Man (Aruku hito, 1990-1991), which has a very good reputation in France, Taniguchi himself explained its importance:

The Walking Man, I feel, was a work that had great meaning for me personally. Before that, I had been drawing the Meiji-period tale called The Times of Botchan. It’s only after I drew that series that my skills henceforth developed in how I staged characters and just overall changes in my technique, that all would allow me to produce The Walking Man.

(Quoted in Tim Lehmann’s Manga Masters: Twelve Japanese Craftsmen, [Manga masutā: 12nin no Nihon no manga shokunin tachi, published in English by Harper Design as Manga: Masters of the Art], Bijutsu Shuppan Sha, 2005, p. 198)

We can roughly call the period from Taniguchi’s debut in 1970 through the mid-1980s as the “Taniguchi Jirō Gekiga Years”. Taniguchi is just one of many artists during this time that appeared as a new face among the postwar generation who drew seinen (young male) gekiga.

When you look at works like his debut piece “Song of the Bird Never Sung” (“Koe ni narakatta tori no uta”, 1970), or “Parched Room” (“Kareta heya”, 1971), both of which were put on display at a Taniguchi Jirō art exhibition,1 you can see his distinctive pictorial style that could express such great detail, as seen in the emphasis he put on the distortions in the folds and wrinkles in clothes and such. That makes us realize Taniguchi was coming onto the manga scene when postwar manga was beginning—starting in the late 1960s—to shift to the mature-male market; more precisely, he had an avant-garde sensibility possessed by magazines like Garo (founded in 1964) and COM (founded in 1967).

Although I just offhandedly wrote the word “gekiga”, it is a term that has experienced many changes in meaning over time. It first referred to (1) a period from the late 1950s when it was became the rallying cry by Tatsumi Yoshihiro and others all the way through the early 1960s, when it was popular in rental manga magazines. It then became (2) a term that includes the works of Sanpei Shirato and Hirata Hiroshi as they were making waves in the mass media. Then, it came to describe (3) the period from the late 1960s through the 1970s - a period during which, while gekiga was becoming the flagship for the anti-Tezuka Osamu style of manga in Weekly Shōnen Magazine, there was also a shift in manga expression towards a more excessive style called “seinen gekiga”, which was often used to describe the postwar generation of artists like Miyaya Kazuhiko and others. Usually “gekiga” is best understood as having these three phases. Taniguchi, in his gekiga period, belonged to this third phase of “seinen gekiga”, of the postwar generation who began to use manga as their own form of self-assertion, as a kind of youth culture and rebellious culture.2

In his debut story, you can feel the influence of Tsuge Yoshiharu and his surreal qualities; also, as an action piece, it has the finely detailed landscapes you would see in a Miyaya Kazuhiko manga. There are other similarities to their styles, such as Taniguchi’s tendency to raise the emotion level with his use of screen tone, the way he distorts his lines, and a rough application of his pen like he is smashing it on the page.

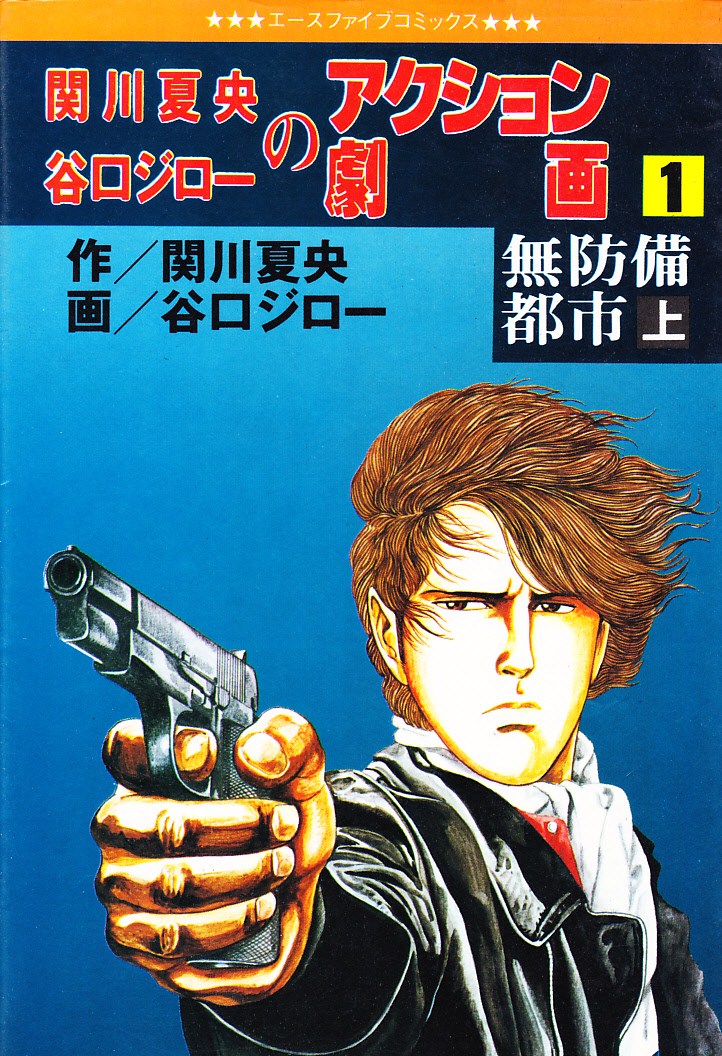

On the cover of the paperback edition of Defenseless City (Mubōbi toshi, Ohayō Shuppan, 1978), which was first serialized in Hōbunsha’s gekiga magazine, Manga Punch (Manga panchi), the words “Action Gekiga” (akushon gekiga) were written in large red letters, bigger than the title itself of this collaborative work with Sekikawa Natsuo. The publisher apparently tried to use this paperback to make readers acknowledge the genre of “Action Gekiga”.

By the way, in the greater context of Taniguchi’s works during this period, we see the appearance of mountains, with his finely detailed drawing style that certainly shows the influence of BD and Moebius. Such illustrations are based on his goal to depict scenery that would tell the story, which was all quite rare in the Japanese manga scene. Soon enough, with The Summit of the Gods (based on a novel by Yumemakura Baku, serialized in Business Jump from 2000 to 2003), he reached a point where his amazing technique could allow him to shape the story construction through his powerful renderings of its snowy landscapes.

The creative combination of Taniguchi and Sekikawa began with their teaming up for the 1977 Go! Killer Dog! (Tobe!! Ansatsuken, featured in Hōbunsha’s Manga Punch), and, for years to come, they continued to build on their creative relationship. Sekikawa tells us that, in the beginning, Fujiwara Tetsu, the person in charge of Taniguchi at the company, said to Sekikawa, “Look, he does pictures great, but when it comes to story construction he’s pretty bad, so could you help him out for me?”3 That’s when Sekikawa took on the challenge of doing his first manga script. However, what Fujiwara actually said may have been quite different. He said he thought what he actually told Sekikawa was that Taniguchi’s works often show a great love of animals and his plots were calm and gentle, so “if we have him pair up with a person who really knows storytelling, then [Taniguchi] will surely get better.”4 Depending on how you read it, it can sound like they thought that if they tried to make “Action Gekiga” [with Taniguchi], it might really sell. This period of time is when Taniguchi and Sekikawa were both in their late 20s.

In the end, Taniguchi and Sekikawa gained commercial value as authors of what would become the “Action Gekiga” genre. The manga market at that time was undergoing a rapid expansion, and it was also building more relationships with other media, like television and movies. The seinen and adult-oriented manga magazines had a huge expansion of their market, so within all that, you saw the diversification of manga genres - so much so that there was a wild flurry and proliferation of new genre names. It was a time when, on the publishers’ side, they would try out and then drop new names in a chaotic trial-and-error way so there was no consistency to them; for their own part, readers just kept on consuming everything they could get from the publishers.

Within this jumble of seinen gekiga magazines, there did develop a hardboiled kind of world full of sex and violence. Taniguchi took the lead among all those artists, and, around the year of 1980, when gekiga began to fall out of favor, Taniguchi found a way to survive even after so many other similar artists disappeared from the scene. I believe that his experience of co-creating with Sekikawa and Marley Caribu [Karibu Mārei, one of the pen names of Old Boy writer Tsuchiya Garon], allowed him to develop his own authorial qualities.

The situation is the same with the artist Kawaguchi Kaiji [known for political and military-themed manga such as The Silent Service]. Kawaguchi made his debut at the age of 21 in Young Comic while he was a college student at Meiji University in 1968. In 1972, Kawaguchi had his first big hit series, The Blood-Stained Badge (Chizome no monshō) in the magazine Weekly Manga Times from Hōbunsha. His early drawing style was actually quite similar to that of Tsuge Yoshiharu’s younger brother, Tadao. It really made you feel like you were looking at someone influenced by Garo. But Kawaguchi was able to stay alive through the end days of gekiga.

Taniguchi, for his part though, had certain qualities that separated him from other artists. From very early on, he developed a taste for BD [bandes dessinées, French and Belgian comics], and that side of him can be seen in the early fermentation of such both a revolutionary style and attitude of manga expression, and a drawing style previously unseen in Japan. For example: he would fully construct scenes where the backgrounds set up the story; his ability to reproduce three-dimensional places like snowy mountains or cityscapes from Meiji-period Japan and their presence; his ability to create self-established pictures by getting rid of unnecessary letters (such as onomatopoeia in fight scenes, words of narration, and so on). I feel that we can see Taniguchi’s inclination to do all these things come into play with the incredible transformation in his artistic power at least around when he does The Times of Botchan with Sekikawa.

With the Times of Botchan series, Sekikawa’s intention was to make “the pivotal change in history the very subject of the story,” and it was an earth-shattering plan for manga at that time.5 Furthermore, Sekikawa believed that this work was a big change in “their pictures and staging,” by which they attempted to “shift manga away from symbolic ways that characters were staged, even though that was one of the most important strengths of manga expression”; Taniguchi drew “landscapes that did the talking” and he “considered if they can illustrate the Meiji period with rich, three-dimensional depth by adding meaning to the places in which people live out their daily lives.” It is through the interplay between [Sekikawa’s] comics script and [Taniguchi’s] comics images—the kind of sparring that goes back and forth [between writer and artist]—that they were together able to achieve such a transformation in manga. We can rather take this change as something Sekikawa learned from Taniguchi’s development.

It truly seems that the relationship the two of them had was incredibly creative and ideal in the sense that each of them kept pushing the other to raise the levels of their respective arts. It is probably for that reason that Sekikawa and Taniguchi do not use the term “gensaku” (script) but “kyōsaku” (co-creation). Taniguchi was able to carry out a never-ending personal transformation and revolution within his art until the very end. I believe that he had the amazing good luck to have met and have been teamed up with Sekikawa in the early phase of his career.

* * *

- “The Walking Man: The Taniguchi Jirō Exhibit” ran from October 16, 2021 through February 27, 2022 at the Setagaya Literary Museum in Tokyo. It then travelled to Kyoto for the International Manga Museum from June 6, 2022 to August 29, 2022.

- I have already touched on this point in an earlier publication for Tokyoite (Tōkyōjin) magazine [Nov. 2021 issue] in “The Challenge for New Possibilities” (“Kanōsei e no chōsen”).

- Sekikawa Natsuo, Satō Toshiyuki, Suzuki Akio (kōdan), “Jikenya Kagyō and 'Bōtchan' no jidai”, in Taniguchi Jirō, Aruku hito, Futabasha, p. 85.

- Fujiwara Tetsu, “Editor in Charge of Taniguchi during His Early Days” (“Wakaki hi no Taniguchi o michibiita henshūsha” (Aruku hito, ibid.), p. 233.

- Sekikawa Natsuo, “The Complete Times of 'Bōtchan'” in The Taniguchi Jirō Collection: Sōseki, Master of the Sullen Pavilion, “Times of ‘Bōtchan’” Part Five (Futabasha, 2022), p. 315.