I.

In 1977, Art Spiegelman was a 29-year old cartoonist whose work over the previous decade had appeared in a dozen underground comix, a few alternative newspapers, some second-tier skin magazines, and Arcade, a monthly he and fellow UG cartoonist Bill Griffith had launched in 1975 – and folded seven issues later. This work had brought Spiegelman little notice or acclaim. Les Daniels' Comix (1970) ignored him. Patrick Rosenkranz’s Artsy Fartsy Funnies (1974) credited his primary contribution to the culture to be the serial masturbator Jolly Jack Jackoff. Clay Geerdes’ The Underground Comix Family Album, photographs taken between 1972 and 1982, excluded him. In A History of Underground Comics (1974, rev. ed. 1987), Mark James Estren displayed the title panel from a three-page story by Spiegelman in Funny Aminals (1972) about a mouse whose father – like Spiegelman’s – was a concentration camp survivor; but if Estrin saw anything special in “Maus”, which was the name of that story, I missed it. The bulk of Spiegelman’s income came from work for Topps Chewing Gum, Inc.

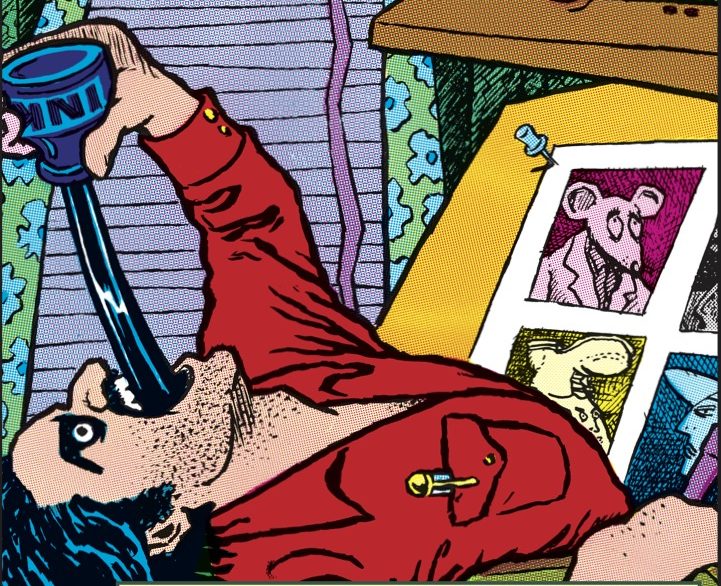

But this work led Woody Gelman, Topps’ art director, to agree to publish Breakdowns: From Maus to Now, an anthology of Spiegelman’s strips, through Gelman’s Nostalgia Press, a labor of love which normally reprinted comics of historical significance. Yet before he could, Gelman took a bath on an Elvis tribute, leaving him unable to pay the printer, so Jeff Rund, whose Belier Press turned out bondage books, some R. Crumb, and two collections of “Tijuana (sic) Bibles” edited by Spiegelman, picked up the tab. Some copies reached stores as being from Nostalgia Press and some as from Belier. Some bore a 1977 publication date and some 1978. Copies cost $8.95. The book measured a shelf-unfriendly 10" x 14" and held but 34 pages, of which 9 were in color and 4 were blank. The cover depicted a distraught cartoonist attempting suicide by pouring ink down his throat, an image repeated a dozen times in varying, optic nerve-unsettling combinations of color.

Spiegelman has said the press run was 5,000, but the printer ruined half. Jeet Heer, in In Love With Art (2013) writes the printer ruined 1,500, leaving 3,500. Belier’s website says the run was 1,667, of which 1,227 were sold, including 108 to Spiegelman. Breakdowns was too ungainly, too expensive, and too odd for bookstores. It had too little sex, too little violence, and too few drugs for the UG market. And it didn’t have a single superhero leaping tall buildings to tempt the masses. In early 1980, Rund gave Spiegelman the remaining 450 copies.

II.

That year, Spiegelman and his wife, Françoise Mouly, began RAW, an oversized magazine which featured work by unknown-to-most cartoonists, foreign and domestic. It cost $3.95, about ten times the price of a comic; but, at a time when most comics were shabby to sight and grubby to feel, their content as shallow as spit and as shackled by clichés and stupidity as, oh, Ronald Reagan, RAW was elegant, imaginative, probing and original. A new generation of often-in or just-out-of art school cartoonists and readers was ready. A 5,000-copy printing sold out, and its circulation soon tripled. RAW appeared annually until 1991, becoming what brittanica.com terms “the leading avant-garde comics journal of its era.”

Spiegelman, who was already expanding “Maus”, began its serialization in RAW’s second issue. Pantheon published it as a two-volume novel (1986, 1991). Still in print today, it has sold millions of copies and won Spiegelman a "Special" Pulitzer Prize, the first graphic work to be so honored. He followed the success of Maus with projects that stood in almost nose-thumbing defiance of capitalizing upon any “brand” he may have created for himself. He illustrated The Wild Party, a largely forgotten, book-length poem from the 1920s. Working with the graphic design master Chip Kidd, he produced a tribute to the often overlooked cartoonist Jack ("Plastic Man") Cole. And he explored his personal traumatization by September 11 in the graphic album In the Shadow of No Towers. After no American publication would touch it due to its anti-Bush/Cheney politics, Spiegelman found a home for it in European newspapers. In 2004, Pantheon published an expanded version, augmenting Spiegelman’s original ten "broadsheets" with reprints of seven turn-of-the-20th century comic strips, all on heavy board stock, each page as thick and as incendiary as a wooden match.1

In 2008, Pantheon re-issued Breakdowns, now entitled Breakdowns: Portrait of the Artist as a Young %@z*!, hardbound, for $27.50. The cover replaced the suicidal cartoonist with a big-nosed, big-footed, airborne middle-aged man, about to fall on his keister, having slipped not on the traditional banana peel, but a copy of the Nostalgia/Belier edition. To this reiteration, Spiegelman added a 24-page, full-color introduction in comic form, which had run previously in the Virginia Quarterly Review (Fall, 2005), a painfully funny account of his development as a cartoonist.

He also added an eight-page “Afterword”. While similar to the introduction in being primarily autobiographical, it is expressed entirely in words. (Illustrations throw light upon the text without moving the narrative.) Focused on the history of the original Breakdowns, Spiegelman takes the opportunity to recognize his need to set himself apart from the UG and dare “to call himself an artist and his medium an art form.”

Though copies remained available online for $20 or less, Pantheon brought out a softcover edition for $25 in December 2022, which I was asked to review.2

Though the 2008 version is larger (140 square inches vs. 108) and heftier (32 ounces vs. 17), the covers and contents, except for the “Afterword”, are essentially identical.

And the “Afterword”s don’t differ much. An “Although” vanishes; “Stupidly, I continued...” becomes “Yet I continued...”; a “startled” becomes a “surprised.” Spiegelman has added that after the Breakdowns ‘78 failure had taught him that, if he wanted readers, he needed a sustained narrative – and that the collection's deconstruction of narratives had shown him how to lay one out – he recognized that his parents’ story had the power to sustain a lengthy one. (He also credits the “fragmentation” approach he adapted in Breakdowns with showing his “shattered brain” how to deal with the trauma he addressed in Towers.) And, though in terms of the lunacies that drape this country at present, it may amount to one bat in Dracula’s castle, he proudly reports that a Tennessee school board was trying to protect children from Maus. (He omits his 2008 judgment that the country was already turning “to shit.”)

The most substantive 2022 addition is an analysis of one of the Breakdown stories, which had appeared in Alternative Media in 1978. It is an instructive, mind-broadening look at the thinking Spiegelman puts into each comic panel and page, though it has the feel of a grade school teacher hectoring students who would rather be at tetherball; and I doubt much of the public had been clamoring for its revival. In fact, I’m not sure why Pantheon felt the need to publish Breakdowns again.

III.

At the core of all three versions is what Spiegelman calls a “scattered handful of short autobiographical and structurally ‘experimental’ comics...” Remove the core and neither the “Afterword” nor introduction need exist. Remove them, and the core remains core.

The most significant of the autobiographical stories are the Funny Aminals “Maus” and “Prisoner on the Hell Planet” from Short Order Comix (1973), in which a young man (“Artie”), recently discharged from a mental hospital – as was Spiegelman – must deal – as did Spiegelman – with his mother’s suicide. Story’s end finds him, overwhelmed by guilt, in prisoner’s stripes, behind prison bars, imprisoned for – and by – her death. Cartoonists, Spiegelman has written, are “forged in a crucible of humiliation and trauma,” which may or may not be true of a greater percentage of cartoonists than of U.S. congressmen or NFL linebackers or stars of the silver screen; but I can think of few people whose development has been shaped by events as horrific as his.

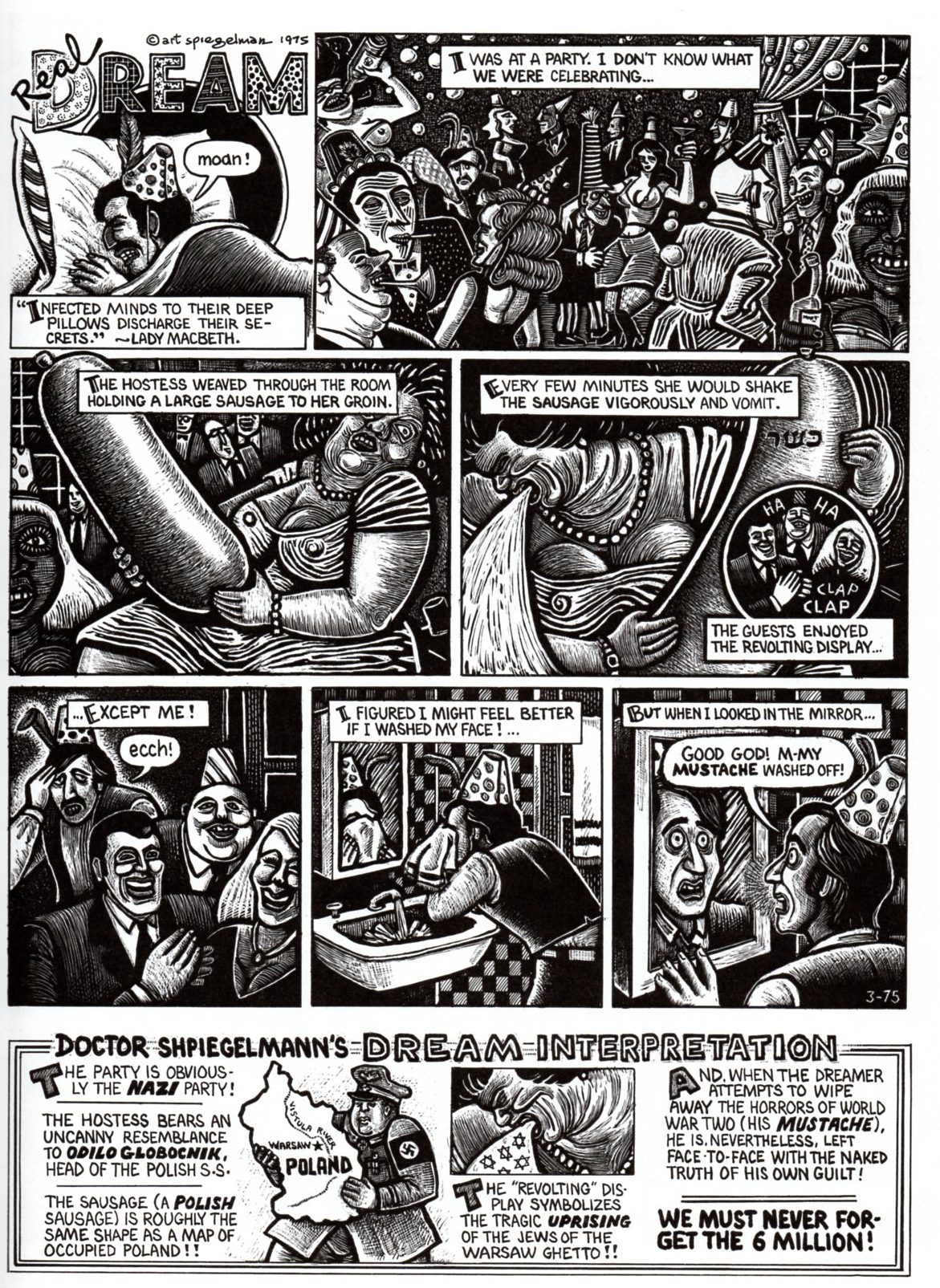

Though Spiegelman had an additional decade of life since his mother’s death to draw on, the remaining stories in Breakdowns avoid direct autobio. Instead, they recount dreams, analyze jokes, riff on depression. Narratives jump around, circle back and forth, tread in place, vanish entirely. Scenes alternate between TV soaps and living rooms, pair realistic speech with surrealist imagery, place characters of vastly different sizes in the same panel, and position smaller frames within larger ones. Words that suit one panel appear in another one entirely. Spiegelman drops references to Cubism and Expressionism and flashes images of porn. He tips his pen to Winsor McCay, the Katzenjammer Kids, Picasso, Freud, Mark Twain, and Mickey Spillane, but does away with character, plot and details of the everyday.

While these shifts in tone and focus may set a reader’s head spinning, they come as somewhat of a relief – and probably to no one more than Spiegelman. After digesting the bone and gristle of his formative traumas, it must have been chocolate ice cream to play with cut-out panels of Rex Morgan, M.D.

IV.

In 1982, four years after Breakdowns' arrival and two after RAW’s, The Comics Journal, then as now a major voice for treating comics as a legitimate art form, published "Slaughter on Greene Street" (issue #74), an extract from an interview with Spiegelman and Mouly published the prior year.3

In the "Slaughter" extract, while editors Gary Groth & Kim Thompson and writer Joey Cavalieri praised Maus for its “maturity” and depth, they were less appreciative of – if not downright hostile to – Spiegelman’s “avant-garde” work. By emphasizing graphics over story, they argued, comics could not involve readers emotionally, leaving them “detached” and unfulfilled. Spiegelman, who had not yet embraced that position himself, responded that learning how stories were constructed was itself a valuable lesson. He was, he said, asking readers to make an effort to dig into what he set before them, not to lap up the obviously present. “[I]n a real work of art, [the audience’s] investment has to be as great as the artist’s.... [I]t ain’t for... [the] lazy.”

Hillary Chute, a professor of art and English, recently called Breakdowns “a deeply formalist book, showing how anti-narrative comics can be...”4 This may be true of many of the pieces in the book; but I think it more significant that Spiegelman did not continue in this direction but veered, with Maus and his later work, back onto a more traditional track. He took what he had learned from playing with time and space, from shifting between “actual” experience and memories, and placed these lessons in the service of narratives on which he would spend the next decades. Janet Malcolm has said that it took Gertrude Stein’s writing the nearly unreadable The Making of Americans to get the “novel” out of her system and free her to become the “strange, wonderful... really interesting avant-garde” writer she was.5 Spiegelman seems to have rid himself of the “strange” in order to focus on the traditional.

By Breakdowns 2008, Spiegelman was ready to write that art’s purpose is “to make one feel...,” or, as Kafka – whom Spiegelman says he began reading at age 12 – famously said, art should be “an axe to cleave the frozen sea within us.”

V.

If the comics world, as represented by the editors of The Comics Journal, was unreceptive to Spiegelman’s efforts to open his genre of choice to the experimental, the pigment-on-canvas crowd was even more resistant to his aspirations. In 1990 – one dozen years after Breakdowns and ten after RAW, – New York City’s Museum of Modern Art opened the exhibit “High and Low: Modern Art and Popular Culture”. About the only comics to sneak in were those whose panels Roy Lichtenstein had appropriated.

A catalog of Readings in High and Low, edited by Kirk Vernedoe and Adam Gopnik, accompanied the show. It contained essays by nine art critics, historians, and professors, accompanied by 225 illustrations, only one of which, by the Blue Chip abstract expressionist Ad Reinhardt, bent “Low” enough to recall anything comic-like. And while the index found room for “body painting,” “found objects,” “graffiti,” “insect illustration,” “postcard art,” “sheet music,” “signboard art,” “tattooing,” and “wallpaper,” “comic” – whether “book” or “strip” – did not appear. Still, I found two references in the text to words-and-pictures art. One recognized Picasso’s preference for “the lowliest cartoonist” and the other Lichtenstein’s for “the crassest... comic strips.” “Lowliest” and “crassest” seem key. The gatekeepers seemed stuck with Gilbert Seldes, who, in The Seven Lively Arts (1924), adjudicated: “Of all the lively arts, the Comic Strip is the most despised...,” “[E]xtraordinarily dreary,” and stuffed with “monstrous stupidity.”

Spiegelman reviewed High and Low in comic form – full-color, multi-panels – for Artforum (Dec. 1980). Through their “myopic choices,” he concluded, the curators had missed the “REAL political, sexual and formal energy in LIVING popular culture.”

The following year, MoMA gave Spiegelman a one-man show.

VI.

Which did not open SoHo or the Upper East Side to Spiegelman and his peers. As the non-traditionalist cartoonist/comic publisher (and current Comics Journal editor) Austin English puts it, “The art world loves to pluck cool images from comics... [but] multiple panels on a wall distract from the salability of one perfect simplified image, which is what [it] loves.” It is not simply a matter of what sells, but what sells for the highest price.

“Galleries and museums are elitist, conservative and expensive,” the artist/cartoonist Ivana Armanini adds.6 “People go to openings only to mingle, eat and drink. Museum and gallery walls don’t connect with life. The comic language goes much further. It is interdisciplinary, hybrid, and fills the interspaces of meanings. It is an open call for dialogue with the reader and your inner voice as the author too.”

Today’s experimental cartoonists have moved far beyond where Spiegelman reached in Breakdowns. “Story” is as foreign to them as it is to a Mark Rothko canvas. (In the writings and interviews of which I am aware, Spiegelman does not cite as influences any “fine artist” more recent than the German Expressionists or Cubist-era Picasso. “I am,” he told the Journal, “more interested in Seurat than I am in Jackson Pollock.”) Today’s avant-garde panels evoke responses in readers but leave each free to find and formulate his own. Words of reaction form in the mind but feel like one is groping for an object lost on a bed, tossing aside pillows to locate it.

In Breakdowns, Spiegelman took apart the components on which narrative ran – the valves and pistons, shafts and chains – not to replace it as a comic’s engine but to reconfigure, modify, soup it up before resetting the comic upon the road. Out of any pool of readers, large percentages are likely to react in a predictable, circumscribed fashion. Love it or hate it, they will agree on what Spiegelman has set before them: mouse or collapsing tower. He has been less about pursuing a particular vision to the exclusion of all else than placing it in the service of a point he wishes to make.

VII.

I suppose an argument can be made that Spiegelman is essentially a journalist. Or a journalist/memoirist. Or journalist/memoirist/historian.

Children's books aside, for most of his adult life, Spiegelman has only written about actual events: personal, historical, or a combination thereof. He is a terrific writer – smart, witty, intelligent, with a uniquely sardonic, self-mocking voice – and a master cartoonist with an encyclopedic knowledge of the form, its present and its past, with which to enrich his pages; but he has never, like, say, Joan Didion, let nothing more than the sight of a blonde crossing the floor of a Vegas casino at 2:00 AM combined with the sunlight at Sunset and La Brea lead him to create Play It as It Lays. (One of his characters dismisses fiction as – appropriating without attribution, Robert Frost on Free Verse – “playing tennis without a net.”) If his parents had not been Holocaust victims, Maus would be a work of fiction; but since they were, transforming them into mice does not make their story that.

And in terms of “events,” it seems to take a MAJOR one – a Holocaust, a Twin Tower bombing – to set his ink a-flow. Maus took Spiegelman 13 years to write. Shadow took 3. In the 18 since, his only solo adult books have been a collection of selections from his (already existing) sketchbooks (Be a Nose, 2009), an analysis of his (already existing) Maus (Meta-Maus. 2011), and a volume to accompany a retrospective of his (already existing) work (Co-Mix, 2012).7

Putting aside Annie Ernaux for the moment, I suppose there is also a question as to whether a journalist (or journalist/memoirist/historian) can be an “artist”. I may be straining for controversy here, but can’t art be viewed like the metaphor favored by defense attorneys in strict contributory negligence states? One drop of black paint and the entire vat of white is spoiled. (If you doubt me, see Postema & Deize's “Artistic Journalism”,8 in which the authors posit poles of “absolute journalism” and “pure art” and chew over the ramifications of rival schools of thought: “facts are sacred” vs. “art pour l’art,” for pages and pages and footnote piled upon footnote.)

But still...

Through Maus, Spiegelman legitimized comics in the eyes of an uncountable number.

With RAW, he (and Mouly) advanced the careers of many cartoonists who might otherwise have remained unknown.

For a decade, he contributed covers and stories to The New Yorker, which, for a cartoonist, was the equivalent of a stand-up comic being asked to sit down beside Johnny.

He created cartoon books for children designed to encourage the little whipper-snappers to read.

He has taught and lectured on comics anywhere that has let him smoke.

He has defended cartoonists’ right to speak out, even when his defense meant he might be shot or stabbed.

It has been written of him, “More than any other living American cartoonist [he] personifies comic books’ newfound cultural respectability.”9

It has been written, “[M]ore than any other single artist or author [he has transformed]... comic books... into serious literature.”10

He has received a Chevalier of the Ordre des Artes et des Lettres from the government of France and a Medal for Distinguished Contributions to American Letters from the National Book Foundation.

I think it may be time for a conversation about a Nobel.

Even a “Special” one.

Now that Bob Dylan has his.

* * *

- My copy, signed by Spiegelman, was purchased at a conference on censorship that year at Ohio State at which we both spoke. I recall him saying my name was familiar but he couldn’t place it, which was not as flattering as it might have been since we appeared on the same page of the program.

- The challenge of reviewing a book which had already been published twice soon became apparent. Maybe I needed a complete set. I had the 2008 version but the first was only available online for upwards of $170. When I found one, with a damaged spine, for $65, I wondered if I could justify the expense.

“If you don’t buy it,” Adele said, “what will you spend the money on? Two weeks' double espresso? You’ll buy them anyway.”

- Between 1981 and 1995, the Journal ran 154 pages of interviews with Spiegelman. As a further insight into my creative process, I read only “Slaughter”’s 12. And, of an entire book of interviews, Art Spiegelman: Conversations. Joseph Witek, ed. (2007), I scanned the Index, checking the text only where my specific interests lay.

- New York Times. Dec. 28, 2022, p. C7.

- Janet Malcolm: The Last Interview (2022), p 49.

- I don’t know many avant-garde cartoonists but these two back up my point, so I’ve run with them.

- He has also collaborated with the photographer JR on The Ghosts of Ellis Island (2015).

- Journalism Studies. Vol. 21, issue. 10 (2020).

- Fabrice Stroun. Artforum. Summer 2014.

- Ted Genoways. vqronline. (Fall 2005).