What was Weirdo?

Jon B. Cooke’s The Book of Weirdo (Last Gasp) brings the legacy of the alternative comics anthology founded by Robert Crumb to the fore. Beginning in 1981, Crumb edited the magazine, published by Last Gasp, for nine issues. Peter Bagge assumed editorial duties for the following eight issues, and then Aline Kominsky-Crumb served as editor through the series’ initial conclusion in 1990. Kominsky-Crumb edited a final, farewell twenty-eighth issue in 1993 featuring a mix of American artists and European contributors she had encountered after the Crumbs relocated to Sauve, France.

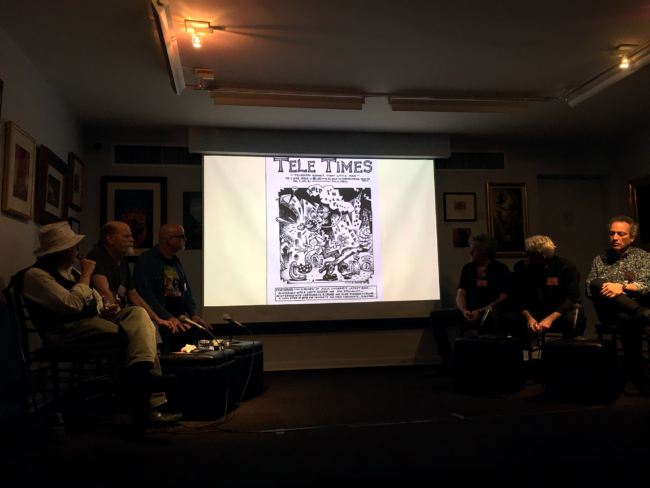

Cooke’s book-length love letter to Weirdo, more than a decade in the making, features long interviews with the magazine’s three editors and more than a hundred testimonials from all but a handful of the magazine’s surviving contributors. The book additionally includes biographies of those contributors who are now deceased and individual sidebars addressing specific topics relating to the magazine. The publication of Cooke’s hefty tome is currently being supported by a series of events across North America featuring various Weirdo contributors in conversation about the magazine and its legacy. On June 6, 2019, a group of New York City-area contributors joined Cooke at the Society of Illustrators for one such conversation. At the Society, Cooke was joined by Kim Deitch, Drew Friedman (who provided the book’s cover artwork), Glenn Head, John Holmstrom, Mark Newgarden, and Art Spiegelman for a wide-ranging conversation. The hour-long chatty exchange pursued various tangents, which at their most illuminating suggested the value of understanding Weirdo in terms of the context of its era.

So what was Weirdo? What space did it uniquely occupy in the landscape of alternative comics within which it was published, and what position does it occupy within a broader aesthetic history? It remains tempting to describe Weirdo in relation to other projects. A sidebar in Cooke’s book notes a perception of Weirdo as the “anti-RAW,” given the two projects’ differing sensibilities and near-contemporaneous publication. While the two magazines certainly presented comics in markedly distinct formats and aesthetic contexts, such a view is complicated by the cohort of artists (more than eighteen by Cooke’s count) who contributed to both publications (including editors Spiegelman and Crumb). Weirdo might also be seen more simply as a continuation of the ethos of underground comix within which Crumb had been a foundational figure (and from which RAW quite consciously departed). And Crumb’s covers for Weirdo, which mimic the cover design of Harvey Kurtzman’s Humbug, place Weirdo in continuity with the historically significant adult satire magazines edited by Crumb’s avowed role model and mentor.

All of this triangulation begins to suggest the space Weirdo occupied. But what was it specifically?

Of the cohort of artists assembled at the Society of Illustrators, very few contributed to Weirdo regularly. Head, Newgarden, and Spiegelman each appeared in its pages only once, and Holmstrom made three contributions to the magazine (one of which was a reprint of material from his Punk magazine). They were all involved with other anthology projects and spoke, essentially, as both insiders and outsiders to Weirdo. Friedman was a more frequent contributor to the magazine, although his work simultaneously appeared regularly in Raw. Kim Deitch was, according to Cooke, Weirdo’s third most prolific artist on the basis of sheer page count. And while Deitch’s presence in the magazine highlighted its connection to Crumb’s underground roots, Deitch offered useful perspective on the qualities that made Weirdo unique.

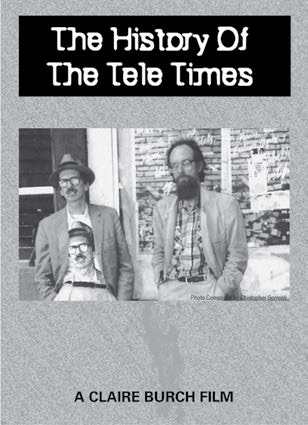

Deitch believes that one important inspiration for Crumb’s Weirdo was the late Bruce N. Duncan’s The Tele Times, a zine that covered culture and street life in Berkeley, California, including the perspectives of homeless persons (alongside material reflecting Duncan’s interest in S&M culture). In fact, Deitch first heard about Crumb’s plans to publish a new anthology from Duncan: “I was living in Berkeley at the time. I was working behind the counter briefly at a comic book store, where I ran into Bruce. And he was a real crackpot, but boy he was an interesting guy and we became friends. And so at a certain point… Crumb hadn’t told me about Weirdo, but he’d gotten in touch with Bruce and he definitely was one of the first people that he was buttonholing to be in the magazine.”

Deitch believed that the particular aesthetics and outsider voice of The Tele Times helped inspire the formulation of Weirdo. “I once said to Crumb, I said, come on now, this magazine is inspired by Bruce Duncan, right? And he gave me a funny look and he didn’t say no. And I think my supposition is not completely incorrect… It was fascinating for me to see: Bruce, shunned by everyone and lifted up and valiantly put forward by Crumb.”

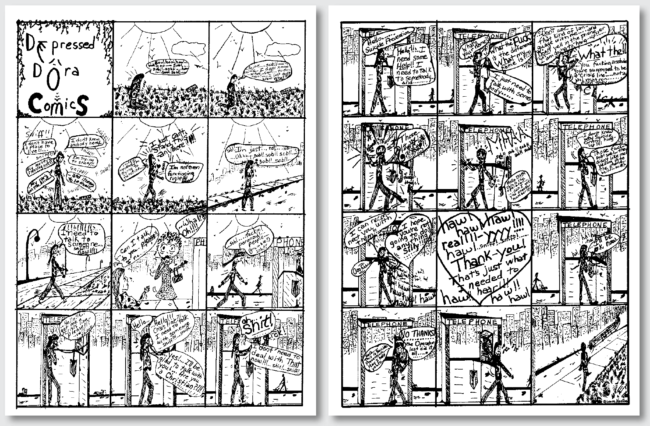

Several of the panelists agreed that Weirdo’s embrace of outsider cartoonists — “outsider” even in the context of underground and alternative comics — was among the magazine’s unique and memorable characteristics. “What I always really dug about Weirdo was that it had this unvarnished kind of originality,” Head said. “So there could be this work like Eugene Teal’s ‘Sunday Frog Funnie’ or the Elinore Norflus stuff, where it really looked like the artist doing the work was completely untutored in art as well as comics. They just didn’t even have a background in it. So you could put Crumb’s work up against it, and a lot of artists’ work up against it, and it was like there was different work from different universes all mixed up in Weirdo. So I was really into that.” Newgarden agreed that among the magazine’s three successive editors, “Crumb tended to go for more what he considered primitive.” When selecting artists to portray on the book’s cover, Friedman was mindful not to only include the magazine’s most well-known contributors. “Weirdo was all about the lesser-known contributors and the fringe artists and the social misfits who contributed to the magazine,” he said. “Weirdo gave guys like Bruce [Duncan] a chance to be published and be seen,” Deitch affirmed. In a sense, Crumb’s openness to artistic outsiders in Weirdo sits in continuity with his embrace of the underground comix work of Rory Hayes, who was very much an artist's artist during his life.

Weirdo’s expanded range was facilitated by Crumb’s own personal accessibility. Newgarden recalled making an early submission to Weirdo. “My introduction to Weirdo was picking it up, looking at it, wondering how this magazine could exist. Immediately thinking, well, I should send them something. Which I did. It was a page that had been rejected by RAW. And I was rejected by Weirdo! … I got a really nice little postcard from Crumb, with tiny little lettering explaining everything he loved about the page and then included, ‘But I’m not gonna run it.’” Peter Bagge later ran Newgarden’s work in Weirdo, compiling a selection of material Newgarden had produced for alternative weekly newspapers.

“When [Crumb] started his magazine,” Friedman recalled, “it was like, OK, he’s accessible, you can actually write him, and he was open to receiving comics from people he had never heard of... I sent him some samples assuming he would not be receptive, he wouldn’t like my style, for whatever reason, because I was doing the stipple work, maybe he wouldn’t like that. But he was receptive and he asked me to do work. So I think he was just really looking for things that he wasn’t aware of that were out there. And he was open to it... And also, he was just very gracious about responding to everything he got, which was amazing… he would always take the time to answer everybody, even if it was something he hated. He was just so generous with his time. I picked up on that early on, and I think he’s still like that.”

Spiegelman suggested that RAW and Weirdo were both “weird DNA mutants splitting off of Arcade in different directions,” referring to the underground-era anthology magazine Spiegelman co-edited with Bill Griffith (and for which Crumb provided most of the covers). “But they both represented different tendencies.” Like Arcade, Weirdo was more deliberately structured than most underground comix anthologies had been, with editorials, letters pages, historical reprints, and text pieces. And Weirdo ran new work by many underground cartoonists who had been featured in Arcade. But Crumb, in his interview with Cooke in the book, also differentiated Wierdo, calling Arcade “too fussy… And I consciously avoided the fussy level that they had done with Arcade.” Crumb, like Spiegelman, learned editorial lessons from Harvey Kurtzman’s various magazines (MAD, Trump, Humbug, Help) that influenced both publications. Arcade first brought that level of editorial sophistication to underground comics publishing, even if Crumb subsequently sought to minimize the laborious rigor behind Arcade in his own anthology.

Whatever the magazine shared with Arcade, it’s also possible to see Weirdo as a direct reaction to Crumb’s experiences with Zap, the 1968 comic book series that he was most closely associated with and that did much to inspire the underground comix movement that followed. With Zap’s second issue, Crumb began inviting other artists to contribute, and by Zap #4 the line-up had coalesced around a core group of seven regular artists. Collectively run, a majority of the seven contributors agreed that no other artists would be invited to participate in Zap, a decision that Crumb disagreed with but acquiesced to. Crumb ran Weirdo differently. “He didn’t want it to be a closed door like Zap,” Friedman said. “He hated that. In fact, he was always resistant to continuing to work for Zap, and they kind of bulldozed him into: ‘You started it, you have to be in there.’ He didn’t want Weirdo to have that vibe. It’s open to whoever wants to send in work.”

Spiegelman recalled one conversation with Crumb: “He said his first impulse when he was doing Weirdo, was he wanted to do a phone-book-sized magazine… and the idea was to not reject anything. And I thought that would be such a fantastic magazine. Talk about something that would age well! To have anything that came over the transom would get published, and it would be like a two, three, four-hundred page magazine, whatever it took… I’m sure Last Gasp didn’t subscribe to that as a publishing philosophy. But that would have been an amazing magazine. Now it’s been replaced by the internet.”

Regardless of the extent of their direct experience with Weirdo, all of the panelists were artists who followed the magazine as informed readers and peers, and many of them were anthology editors themselves. “That was a decade of anthologies,” Newgarden said. “RAW and Weirdo were sort of these two poles that held up a bigger tent of a lot of other anthologies that were coming out at the time.” In addition to appearing in RAW and Weirdo, Newgarden co-edited Bad News with Paul Karasik. John Holmstrom co-founded PUNK magazine, and then co-edited Comical Funnies with Peter Bagge before Bagge succeeded Crumb as editor of Weirdo. Spiegelman, of course, co-edited RAW with Françoise Mouly, and Glenn Head co-edited Snake Eyes with Kaz, who contributed to both RAW and Weirdo. “Like a lot of people reading comics then, I thought about what a good anthology might be,” Head said. “So that was when I got hooked up with Kaz and did some issues of Snake Eyes. And it was really influenced by Weirdo in terms of that kind of lowbrow thing. It wasn’t very arty, but it was probably more polished than Weirdo. But it definitely grew out of that same kind of mindset.” Triangulation again: more lowbrow than RAW, more polished than Weirdo.

The covers to RAW #8 (1986) and Snake Eyes #1 (1990), both by Kaz

The covers to RAW #8 (1986) and Snake Eyes #1 (1990), both by KazOver the course of the discussion, a parallel portrait began to emerge of the alternative cartooning scene in New York in the early 1980s, in which the California-based Weirdo played a long-distance role. In addition to the anthologies noted above, Peter Kuper (who was in the audience at the Society of Illustrators) and Seth Tobocman launched World War 3 Illustrated. Kuper, like Weirdo contributor Dan Clowes, attended Pratt Institute, but sat in on Art Spiegelman’s class at SVA. Friedman, Newgarden, and Holmstrom also attended SVA, where Harvey Kurtzman and Will Eisner were also teaching at the time. Other SVA students included Kaz and Peter Bagge. These artists, both as students and recent graduates, contributed work to these anthologies — big and small, durable and short-lived — and to other paying venues. “I mean Drew, you remember, we were selling our stuff all over New York,” Holmstrom recalled. “We were in Screw, we were in High Times, anybody who would pay us a buck.”

“Well, yeah, I was all over the map because I was doing work for Comical Funnies with you guys,” Friedman replied, “but I was also in RAW with Mark and Kaz, and we felt like we were big shots because we were still students in Visual Arts and all of a sudden Art and Françoise invited us to be in the first issue of RAW, and it was like, ‘Woah!’ And that was thrilling, and RAW paid twenty-five dollars a page, I remember that. And then Weirdo came along, and Robert was offering fifty dollars a page. So I was like, ‘Holy shit! My life is just made now! I don’t have to worry about anything!’ But reality struck and I had to pay a rent all of a sudden, I had to really look for actual income. But that was just a thrilling time, I think, to be around. There was just a lot happening in 1980.”

The essential meaning of any comic is not located in any individual panel, but in their juxtaposition and in the accumulated meanings that emerge between and among them. The same might be said of an anthology: no single contributor entirely defines an anthology project. Rather, its overall character emerges from the juxtaposition and accumulation of individual comics by many different artists. A single conversation, like the one that took place at the Society of Illustrators, can only represent a few, fragmentary perspectives on its larger overall subject. Cooke’s The Book of Weirdo attempts to go the distance by providing a forum for the voices of nearly everyone involved. But a panel like this can model the interplay of subjective voices, which is precisely what a well-edited anthology constructs. While it’s true that what Weirdo uniquely brought to the fore in “a decade of anthologies” was the inclusion of so-called “outsider” artists like Bruce N. Duncan, Elinore Norflus, and Ace Backwords, Head is correct in noting that what made this significant was their presence among rising artists like Kaz, Friedman, and Julie Doucet and more established artists from the underground generation including Crumb, Deitch, and Kominsky-Crumb. “In looking back on it, it sort of held up better than I would have guessed,” Newgarden said. “There’s a real vibe there that’s kind of gone now.” Weirdo’s dedicated eclecticism, filtered through the individual perspectives of Crumb and the magazine’s subsequent editors, make it an anthology that remains worth talking about today.