Any curious reader expecting new insights in Stan Lee: A Life in Comics, a new biography from Yale University Press’ austere Jewish Lives imprint, will figure out that there aren’t going to be many before they are done reading the first chapter. Author Liel Leibovitz, who has previously written biographies of rock ‘n’ roll greats your dad likes such as Leonard Cohen, opens the book with a hook, a pivotal, life-changing incident in Stan Lee’s life: the creation of the Fantastic Four. Apparently, things aren’t going too well for Lee, his comics career in the doldrums amid a Comics Code era crash, and his heart isn’t that into “spending his days working on anodyne stuff like the foible of two models named Millie and Chili or the adventures of a diaper-wearing dragon.” About to quit and abandon comics for good, Lee’s wife Joanie encourages Stan to make his latest assignment from publisher Martin Goodman, to write a superhero comic to compete with DC’s Justice league, the ambitious literary work he always wanted to write instead (4):

“Look, Stan,” she finally said, “if you want to quit, you know I’ll support you. But think about this: If Martin wants you to create a new group of superheroes, this could be the chance for you to do it the way you’ve always wanted to. You could dream up plots that have more depth and substance to them, and create characters that have interesting personalities, who speak like real people.” It could be fun, she said, to experiment a bit; besides, she added with a smile, “the worst that can happen is that Martin gets mad and fires you. But you want to quit anyway, so what’s the risk?”

It’s a moving exchange. Its source is a work of fiction. Leibovitz’ endnotes inform the curious reader that Joanie's words are “quoted in Stan Lee, Peter David and Colleen Doran, Amazing Fantastic Incredible: A Marvelous Memoir (New York: Touchstone, 2015).” This is a graphic memoir for the general market, officially sanctioned by Lee with his name on the cover, but clearly a dramatization that trades more on the myth than the man - these words are most likely not Lee’s own recollection of events but the creative efforts of journeyman comics writer Peter David with at best some general guidance by Lee, more likely that of a publicist. This is not a reliable work to be citing in a biography from an academic publication unless absolutely necessary, and yet here it is, mere pages into a book from Yale University Press with little more than a sparse and misleading annotation to guide us to its source. I do not have Amazing Fantastic Incredible in front of me, but would not be surprised if Stan Lee: A Life in Comics follows roughly the same narrative beats as that piece of legacy marketing - Leibovitz’ biography is far more concerned with the modern myth of Stan Lee than the human life of Stanley Martin Leiber.

Despite its title, Stan Lee: A Life in Comics has remarkably little to say about Stan Lee. What Leibovitz really cares about are the Marvel superheroes, their powerful brand, and the brand of their creator. Judging by this book, it seems as if most of Stan Lee’s life occurred between 1958 and 1968, after which he did not reemerge until the 90s when he began making cameos in movies. Even when Leibovitz discusses Lee’s career in comics, he passes over the non-superhero work almost entirely aside from dismissive asides about giant monsters named Droom paying the rent. This may not seem significant, but when one considers that these are the aspects of Lee’s career that readers may be less familiar with, it is a problem. Perhaps Leibovitz has ignored this aspect of Lee’s work because it would puncture the myth of Lee the literary innovator - those iconic, all-different origin stories from Fantastic Four to the Hulk and Spider-Man bear more than a passing resemblance to the genre formulae of horror and monster comics, with their ghoulish mutations, paranoid egotists and fitting comeuppances. It’s telling what work in Leibovitz’ eyes deserves to be bestowed with literary greatness in spite of itself and what is so artless to be nothing more than paycheck fodder lost to history – what is reputable is what is remembered, the blockbuster-inspiring.

Leibovitz lavishes an absurd amount of attention on Lee’s Marvel superheroes, often at the expense of any real insight into Lee’s life while he worked on these creations, and even these insights are vapid. Over 160 pages, half are devoted not to Lee’s life and career or even to the comics and media bearing his name but to breathless plot summaries of a handful of Marvel Comics, superhero characters and origin stories. These synopses eat up so much space that he only actually discusses at length about a dozen of the comics published under Lee’s name, and wastes space on more than a few that weren’t -- why does a biography of Stan Lee devote numerous pages on comic books written by Chris Claremont and Karl Kesel?

Leibovitz dedicates entire chapters to this nonsense, two on the Fantastic Four, one each for the Hulk, Spider-Man and X-Men, operating in a mode clearly inspired by the Superheroes and Philosophy series of books. Classic characters and plotlines are described in brief and then compared to an aspect of Jewish scripture, folklore or philosophy which is subsequently summarized in the same level of depth. The comparisons -- let’s not pretend they are readings -- are either so obvious as to be thoughtless (get this folks, has it ever occurred to you that The Thing is a modern take on the golem of Jewish folklore) or so tenuous as to stretch credulity (Ben Grimm and Reed Richard’s dynamic in the Fantastic Four recalls the authorship of the Talmud! Is Peter Parker like Cain slaying Abel when he fails to stop the robber who shot Uncle Ben?)

There is little to support these claims, and Leibovitz is aware of it -- he prefaces his first interpretation with an explanation that reads like a garbled misremembering of the concept of a counter-reading -- but they are essential to his shallow and critically vapid proofs that Marvel comics are important works of Jewish literature. It is a lazy way to talk about comics and an offensive depiction of the Jewish experience. Stan Lee’s collaborations with Jack Kirby are absolutely vital works of Jewish art that profoundly reflect the Jewish experience of 20th century America and they matter to me as such, but analogies to the lore of Jewish faith can hardly contain the extent of the experiences that Kirby especially reflected in his stories. And Kirby’s later Marvel and post-Lee work is more genuinely Old Testament anyway, which of course sails over Leibovitz’s head almost entirely. Maybe the polytheism tripped him up? Leibovitz is noticeably silent on characters like Thor and Doctor Strange throughout, who are apparently a little bit harder to sell as products of a Jewish epistemology than such paragons of the Torah as the Incredible Hulk.

Where Leibovitz’s ruminating on the specialness and special Jewishness of Stan Lee’s Marvel crosses from merely being silly and meaningless to baldly offensive is when he inevitably must downgrade the surrounding work of the era by other Jewish creators to elevate Lee’s. According to Leibovitz, while Lee did not create Captain America, he created the character’s personality and elevated the serial closer to literature in his all-text backup, written to fill space, where unlike the serious (and therefore generic, not creative) action hero of the main comic, Lee’s Cap makes jokes, which is apparently enough to set Lee apart from the non-literary, less authentically Jewish hackery of the scenarios developed by those lesser creative talents Joe Simon and Jack Kirby.

It’s one thing to make flimsy claims of literary greatness off of zippy one-liners and tonal difference, but Leibovitz takes the reader into truly inappropriate and credulity-straining territory when he deigns to pick on the inadequate Jewishness of Superman, who, credentials like the Hebrew-sourced name Kal-El aside, really “bears a greater resemblance to Christ” than Moses. Superman has powers and defends the weak from the greedy, so Siegel and Shuster created a Christ figure! Never mind heroic Jewish traditions from Samson to Moses or even the theories of fellow Jewish Lives subject Karl Marx, only Christians have ever thought the poor needed saving. To be a Jewish tale there must be moral rot and impotence, this apparently being our defining character.

Not every Jewish person would find Leibovitz’s reasoning here dubious -- Leibovitz clearly didn’t -- but speaking from my own Jewish perspective I find this line of reasoning actively insulting. Does Leibovitz simply believe no heroic or messianic iconography existed before Christ? Or after? Does he view the diasporic dreams of Siegel and Shuster as nothing more than “Christ without Christianity” paving the way for the more real secular Judaism of Stan Lee’s genius? Do you suppose Leibowitz would reckon Kirby’s New Gods “paganism without pagans”? To Leibowitz, it seems all that can make a comic serial truly Jewish is its connection to the Old Testament, and the Old Testament is defined by the absence of anything resembling Christ or his teachings. To his credit, Leibowitz does not make the mistake of so many pop journalists of asserting Superman’s Christliness without citation (34):

It’s no coincidence, then, that when Warner Bros. released the 2006 dud Superman Returns, it directed much of the publicity efforts at the evangelical community, marketing the movie as a Christian parable for the ages.

I have a bit of trouble seeing what the perspectives of a 2006 marketing push for a multi-million dollar “dud” have to offer in understanding what readers made of the exploited labor of two Jewish boys from Toronto in the 1930s. Leibowitz goes on to back this up a little further with a multi-paragraph description of Mark Millar’s Red Son, another ‘00s work from a decidedly non-Jewish perspective, and considers his case against the characters of non-Stan Lee Jewish comic creators as good as made. One misses the days when the interrogators of the Jewish people at least had the patience to twist our own words.

To give Leibowitz’s biography some credit, when he steps away from his dubious perch as pop cultural metaphysician he provides a more lucid account of Lee’s storied life than one might expect. For all its faults, A Life in Comics mostly provides a measured biographical account culled scrupulously from interviews and recollections, largely out of the magazine Alter Ego -- about as valid a source for industry stories as we can expect -- Lee’s autobiography, and Sean Howe’s Marvel Comics: The Untold Story, which anyone interested in the history of American comics should read instead of this book. As such, Leibovitz cannot help but ultimately provide a portrait of Lee as he lived, a pathological liar, self-aggrandizer, brownnoser and avid union buster. Leibovitz's attempts to obfuscate, downplay, or justify Lee’s trademark tendencies toward self-promotion at the expense of everyone around him take such absurd rhetorical steps and are so consistently undermined by every beat of the biographical narrative he has assembled that a half-awake reader may benefit from studying their internal contradictions.

This is not to say that we have an unflinching or complete portrait of Lee’s life whatsoever. The aforementioned lacuna from 1968 to the mid-90s is extremely problematic -- we rush from a sentence about Lee moving to California in 1981 to “Never one to sit idly by, Lee decided to explore cyberspace” (147) in a page or two that mostly summarizes Sean Howe’s narrative of Marvel’s messy business trajectory in the 80s and 90s. What are we to make of Lee’s enduring friendship and business partnerships with Hugh Hefner? Leibovitz has absolutely nothing to offer.

Of what life he does cover, Leibovitz makes egregious omissions as well. Of all of Lee’s working relationships in comics, only his connections to Martin Goodman and Jack Kirby are discussed at length. From this book, you would believe that the only artists Lee worked with in the 60s were Kirby and Steve Ditko, and the latter only on Spider-Man. John Romita Sr. is briefly acknowledged taking over on Spider-Man after Ditko quits, but he is barely a character in the book. The likes of Wallace Wood, Don Heck, John Buscema, Marie Severin and others are nonexistent, nor is there an inker, letterer, or colorist in sight, to say nothing of the (at least) dozens of employees under Lee’s supervision in his decade managing Marvel whose names don’t make it into the credits of comic books. Even Lee’s secretary, Flo Steinberg, the Fabulous Flo of the Marvel Bullpen, barely factors into Leibovitz’ account for more than a sentence. Leibovitz cites the interview magazine Alter Ego frequently -- I wonder if he encountered the interview with African American cartoonist Cal Massey which Austin English quotes in his still-vital essay “The Strange Case of Stan Lee” (also for the Comics Journal), in which Massey recalls Lee making degrading, racist jokes to his face. Leibovitz only deals in legends, and that means we only talk about the people important enough in Lee’s life to officially matter to the myth, which are the names in a small handful of comic books that spawned successful intellectual properties.

What Leibovitz does have to say about Lee’s relationship to his artists should, I suppose, be given credit for acknowledging at all that they were difficult and often damaging relationships, but it is a softened and misleading portrait. His relationship to Jack Kirby is given attention, and many of Kirby’s lifelong grievances with Lee are discussed at length and sympathetically. With the exception of the Silver Surfer, however, Leibovitz ultimately avoids explaining at length the degree to which Kirby was actually involved in the creation of his characters and stories. Leibovitz’ discussion of the “Marvel method” – wherein Lee’s artists would expand a full comic from a paragraph by Lee, usually written after a conversation with the artist, for Lee to add dialog to following notes left by the artist – is relegated to a short paragraph not written with much attention to clarity. Lee’s mid-60s move to having his artists plot many of their stories entirely without Lee’s involvement whatsoever, for which they even received credit after not a little fuss, is barely noted at all and quickly forgotten. Lee stole the work of other people and profited from exploiting their imagination – the extent to which he did is debatable but that this defined his practice as a “storyteller” at his career peak is not. This is not a minor omission because it is the story of Stan Lee. That was his life, that was his contribution.

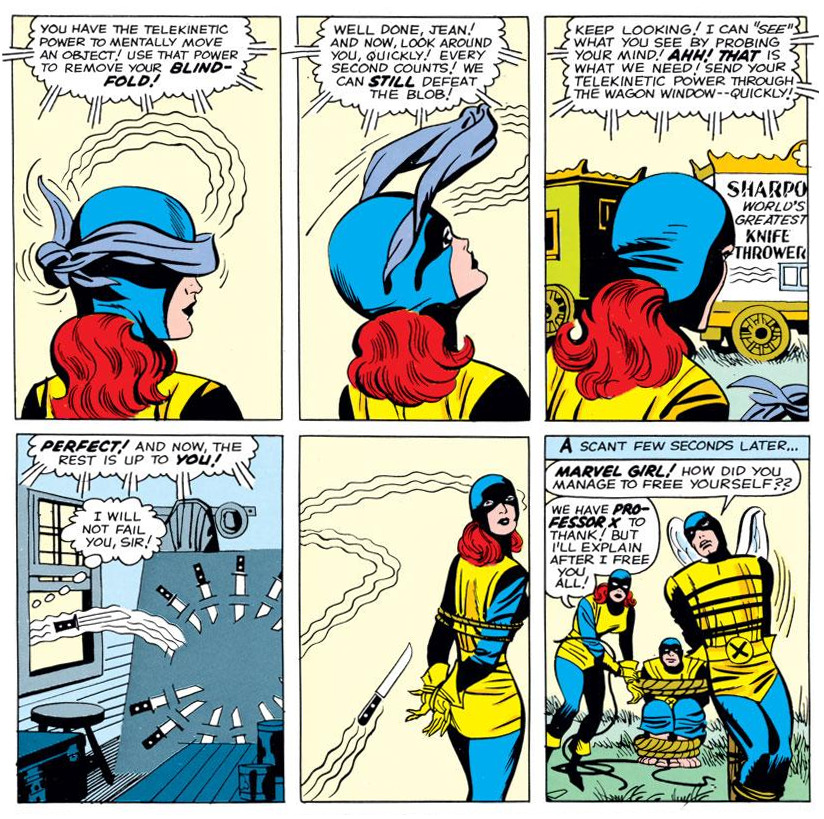

While hiding this core element of the history of his favorite superheroes, Leibovitz plays a dirty trick. In a few places, Leibovitz takes time aside to discuss the merits of Kirby and Ditko’s artwork, the virtues of their style. This is more than some authors would bother, to be fair, but in doing so he further obfuscates and conceals that the plots and concepts of the Marvel universe he extols are at least partially theirs rather than solely the genius of Lee. Indeed, it would not look good to depict Lee as the scripter of stories already finished by others because we would find him not only a thief but a censor, and not a very appealing one at that -- the blog Kirby Without Words demonstrates aptly not only that Lee worked overtime in his scripts to revise Kirby’s plots, especially to ensure that women never acted with aggression or agency without a man guiding her with orders.

It’s telling that when Leibovitz describes a reading of the Fantastic Four’s Ben Grimm as a working class Jew (like Kirby) at odds with his more privileged peers (like Lee) he is fast to dismiss this interpretation as reducing the characters to “a narrow socioeconomic prism.” (61) I don’t think there’s anything inherently shallow about this reading, although it certainly requires elaboration that this broad dismissal cannot provide. At the very least, there is more in the comics themselves to support this reading that Leibovitz is so eager to rush past than his claim, elaborated over several pages, that Mister Fantastic is an analogue for the dybbuk of Jewish folk tradition. One need not be a doctrinal Marxist to get the feeling something has gone very wrong when an author attempting to discuss a life and a body of literature sneers at the narrowness of class struggle and material conditions while indulging in fantasies of pop culture knick knacks cosplaying the folklore and mystics of an ancient faith.

As a competent writer for a university press, Leibovitz’ narration of Lee’s life story finds itself in a hilarious bind, depicting events as they happened with citations from valid sources (albeit frequently dubious and often secondary). Unable to draw conclusions from what he finds, Leibovitz diverts the increasingly vivid image that even the most squeaky clean portrait of Lee quickly provides. Often Leibovitz accomplishes this by chalking Lee’s behavior up to the desperation of his great depression-era youth and Jewish heritage, not technically incorrect but frankly offensive when deployed as an excuse for Lee’s crueler side, considering most of his peers at Marvel were also Jewish and also grew up poor. The people Lee exploited were a lot like Lee demographically, but they did not, for example, take credit for other people's work or snitch on coworkers planning to demand a raise. They also were not the nephew of Marvel’s publisher Martin Goodman. The constant evasion of negative or unpleasant imagery reaches a disturbing pitch when Leibovitz briefly sums up the horrific elder abuse Lee suffered late in life along with the sexual assault allegation made against Lee by one of his nurses around the same time in a single paragraph, conflating the incidents as “allegations” which “surfaced” but thankfully “did little to tarnish Lee’s image.” (161) For Leibovitz, it seems, #metoo isn't welcome to make hers Marvel any time soon.

Leibovitz’s myriad excuses for Lee’s frequent and evidently reprehensible behavior, that Lee was the class clown, for instance, wear a little thin at the millionth description of Lee insisting on playing on his ocarina at every meeting or driving around in a Rolls Royce while working for the U.S. Army as a propagandist. But the most absurd rationale, one that Leibovitz rolls out in his more pivotal episodes of pathological lying and self-promotion is that Lee’s behavior was simply a part of his literary genius and his great plan to raise America’s spirits. In his chapter on Lee’s youth, titled beyond parody “Stan Lee is God,” Leibovitz disproves an oft-repeated, Trumpian anecdote by Lee about winning hundreds of dollars in a weekly newspaper writing contest that awarded $20 to the best entry by winning first place every week -- he was actually awarded seventh place, exactly once. Realizing perhaps that this sets the tenor for a characterization of Lee as a pathological liar rather than a great Jewish author, Leibovitz follows with a stunning rationalization that is repeated in many shapes and forms throughout his account of Lee’s life story (20):

To look at Lee’s embellishment as a lie, or to merely excuse it as a figment of an anxious teen’s insecurities, is to miss the point. Lee had it just right: the anecdote is worth retelling because, like one of the origin stories he was later so adept at creating for his heroes, it shows him, an ordinary kid, discovering his superpower. Just what that power was is harder to define; it’s neither writing, really, nor self-promotion. Instead, it’s the gift of plugging in to what filmmaker Werner Herzog called “the ecstatic truth” that hums just below the surface of art and life alike, frequently escaping the ears of those attuned only to the thud of recorded facts.

As Lee would learn decades later, there was hardly a better job description for a maker of myths, whose task was not merely to invent colorful new worlds but to look deep into our own and find there new meanings buried underneath the rocky terrain of inertia and conventional wisdom.

According to Leibovitz, lying, stealing, vanity, and betrayal are not the hurtful actions of a deeply flawed man but marks of literary greatness. Not only are these the virtues of a great storyteller, in fact, but traits of Jewish exceptionalism, as we are later regaled with justifications of how this Leiber who wrote with the gentile pen name Lee was inspiring Jewish kids by puffing himself up. It is funny that Leibovitz refers to Herzog’s ecstatic truth because Leibovitz has completely avoided finding that truth, staring at the drab facts and turning away from anything humane that could be found in their confrontation. Leibovitz cannot find anything human and valuable in Lee’s cruelty, so he obfuscates and sugar-coats. There is no reason to say that acknowledging Lee’s behavior in life makes him nothing but a cartoon villain, and there is absolutely greater insight into the work bearing his name to be found when read with awareness of the conflicting voices dueling within them. But to Leibovitz, any interpretation that would mar the mythological, marketable persona of Stan “The Man” Lee, would make him not important, not lovable, not human, not valid. There is a sadness, a complexity, a pathos and indeed a brilliance to Lee’s life that does indeed speak to the experiences of American Jews of the past century, but Leibovitz cannot grasp at it because he loves the myth too much to confront a powerful story.

Ultimately the skeptical reader of this biography must ask themselves: what is it that is so special about this myth of Stan Lee, the cultural mirage that Leibovitz is so desperate to protect from true stories of abuse and being abused alike? As best as I can tell, what Leibovitz has set out to preserve is the integrity of Stan Lee’s cameos in the Marvel movies. The final chapter of Leibovitz’ book on the Jewish Life of Stan Lee is in fact largely dedicated to the genesis of Marvel Studios, lauding the creative genius of Kevin Feige (so much like Stan Lee!) and the pluckiness of the little production company that could, with a little bit of help from $525 million in credit from Merrill Lynch and a rapid acquisition by the Walt Disney corporation. Leibovitz praises Iron Man and its Hollywood offspring as a moment in pop culture history comparable to the birth of jazz and chillingly compares the virtues of Marvel Studios slick product to the message of hope offered by the Obama administration – fitting perhaps, when one considers the number of anonymous brown casualties appearing as extras in both Iron Man and Obama's foreign policy. For Leibovitz, Stan Lee was not a life or even a life in comics, Lee is the cute old man who served as the mascot for a string of blockbuster movies, preserved in them perfectly like a prehistoric fly trapped in amber. Anything contrary to that sentimental image, be it negative or just more nuanced, is given little room to breathe, all for the sake of preserving the icon’s sanctity. This biography was written by someone who hates Stan Lee and cannot bring himself to admit it.