1.

My first encounter with Stan Lee came sometime in 1993, at age 10. A friend showed me this card, which was already a few years old, and it commanded all my attention, as if it were some kind of Ark of the Covenant type artifact. I knew every character referenced and loved them. Every one made by a single person? The concept of so much originating from one mind was a genuine thrill I won't soon forget. It was probably more memorable than the work itself, the moment in time when I stared at this card. Instant respect for this person, a kind of allegiance, was registered.

But there was something wrong with the image, at least for the 10-year-old eyes viewing it. Lee is inviting the viewer to celebrate his act of creation, but his smile felt twisted, without pleasure. He didn’t seemto share the love for these characters that everyone else had. And up top, we have a sign of some other view of the man coming into play: a devil's horn and a top hat.

Lee was, instantly, a confusing figure to me and he remains so. My entry into comics (outside of reading Tintin or uncomprehendingly looking at Krazy Kat) involved a pre-adolescent fascination with the drawings of Jim Lee and Todd McFarlane. Comics were drawn by artists, and the artists accounted for much of what made a comic a comic, at least in my early understanding of them. Now, here was a man presenting himself as the God of the comics I loved, accompanied by text jovially explaining that while he was "aided by some of the most talented artists in the comics biz, Lee created virtually the entire Marvel Universe, and revolutionized comic book writing as we know it today." [Italics mine.] The card "wasn't big enough" to list all his creations. This man was responsible for what my friends and I adored most, but something didn’t seem right. At this moment, I’d still never heard of Jack Kirby, let alone Steve Ditko, Wally Wood, or Bill Everett. They didn’t have cards in this set, of course.

2.

When Lee passed away last week, non-comics world friends reached out to me to express condolences. They knew I loved comics and that I'm interested in the history of the medium... Clearly, this was a loss, right? A melancholy day? When I responded by trying to explain what a strange and confounding figure Lee was, and that he didn't exactly create the characters the media was saying he did, I found myself at a loss to explain why. Lee wasn't standard, he didn't just take credit for something that he had nothing to do with, so it couldn't be explained in a black and white way. He did have a large role in what Marvel was (and is), much of it positive. Why was he not what he claimed to be? It wasn’t easy to summarize and it felt exhausting, even ridiculous, to try.

My genuine love for people like Kirby and Ditko made that confusion seem cruel, intentional, a lasting way to obscure the work of actual creativity in the collective consciousness—a comic-book-villain type of crime. To get at the subversion, one had to bring up the 'Marvel Method,' which no one with a passing interest in these things should be expected to understand (although journalists covering Lee's passing could certainly do a little research). The Method is an odd system to base a major media company on, and yet the strangeness of it, the counter-intuitiveness involved, served Lee well in regards to his legacy. I’m sure, at the outset, it was simply a way to produce comics faster and cheaper by letting the artists be cartoonists. But no one really understands what cartooning is, and so Lee becomes a figure in people’s minds, the idea of the absolute heights a comic book can contain. True embodiments of the forms potential, Wood or Everett, exist as cultural foot notes in comparison, as if André Derain is the first name and Matisse the second.

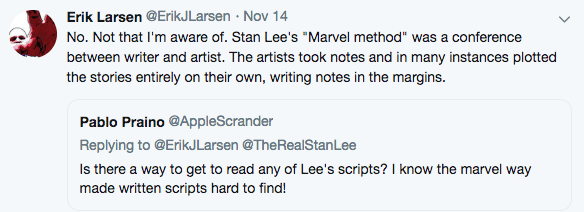

The Marvel Method has been discussed at length on this site and many other places, but for our purposes, let's summarize it quickly. The writer offers the artist a verbal (as explained by Erik Larsen above) summary, the artist jots down some notes, plots the summary out, breaks it down into 20+ pages, draws it, and offers notes on the margins, this time for the writer as a guide. The writer then adds dialogue, copy.

Lee is credited with the 'creation' of the Marvel Universe and it’s fine that there are no typed scripts of his major moments of genius to donate to the Smithsonian—-he ‘wrote’ with The Marvel Method. Part of the murkiness and strangeness of Stan’s legacy is that people seem to enable the simplicity of explaining away this conundrum. Longtime former DC comics editor and president Paul Levitz, in a recently penned remembrance, related this anecdote:

"I worked with all your artists, Stan, and no one ever got as great work out of them as you did. Never mind Jack and Steve, you got the best work of their lives out of Don Heck and Dick Ayers. Good guys, incredibly professional, but you got so much more out of them than I did."

He smiled, and the 'avatar' started to come on. The Stan Lee we know from the stage said, "Every time I sent Dick a script--he was doing some western, I don't remember what it was--he'd call and say, "What do you want me to do with this one, Chief?'"

"And I'd say, it's a western, Dick, I want to see the spurs shining and hoofs flashing..." and Stan never got to finish, because I was laughing out loud.

This description of Lee’s process—essentially, give me more cliche and plenty of it! And make it loud!—amazingly comes after Lee says to Levitz, "But Paul, I wasn’t much of an editor. I wrote almost all of the stuff myself."

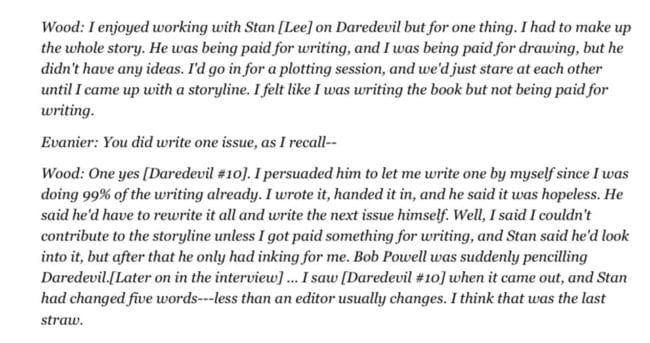

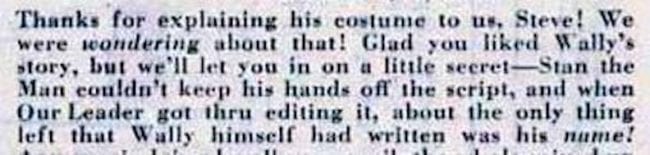

Lee never talks about ‘writing’ these scripts he sends Ayers (‘I don’t remember what it was’ as always, and the fact that Ayers has to place a call after receiving the script to ask what is needed is not addressed) but he does discuss his editorializing, the part of the creative process he was always most comfortable discussing. Somehow in people’s minds, the two activities (writing and editing) become merged and then transformed, with Lee victorious on the other side as a visionary writer. One might think it would be enough to be a gifted editor and art director. Why push for something else? The question screams itself at us when we observe Lee’s behavior with Wally Wood:

Those enjoying Daredevil at the time, before issue 10, were reading Wood's creative choices: the pacing, the ideas, the way characters moved on the page, the way they landed punches, etc. They were enjoying the work of a cartoonist. Lee's dialogue was probably also appealing, but nothing Wood couldn't easily emulate. As Wood notes, Lee didn't need to change much of anything in the actual script. What he did, immediately, without a doubt need to change was the possibility that people might think Wood was writing these books:

"Our Leader" is a man who had private conversations with one of the best artists to ever work in comics, offered nothing, put his name on the books anyway, and held on to the credit even after artists like Wood met tragic ends. It may have begun as a desire to pay Wood (or Ditko or Kirby) less, but quickly merged into a maddening desire to be seen on the same creative level. As long as Lee is doing some strange form of writing, it's a particularly tricky grift to explain. And an odd one at that, since taking credit for choosing to put Wood on such a book is more than enough for a legacy: a strong bit of editing. But, of course, Julius Schwartz, Mort Weisenger, or Bob Kanigher, all excellent editors, are not on the lips of Bill Maher (or whoever was the Bill Maher of the moment in time when they passed). They are merely respected within their field, not cultural icons. Being a visionary is where it’s at.

What is cartooning to most people? It’s a cartoon, like Bob’s Burgers or something. Cartooning as writing is a foreign concept to even the most dedicated cultural student. Wood’s choice to compress a concept into a certain number of panels, to have a character emote in a certain way, to have a specific scene happen at dusk, making choices, is what we’d call cartooning, and a real form of writing, one that asserts itself decade after decade. Lee’s conversations with artists is, clearly, much less a writing practice than Wood’s and so it doesn’t make sense that people would accept his suggested role in things for so long, except when you see Lee falling over himself to diminish Wood. He kept the public story of his creation and writing consistent, from that '60s letter page to the card I discovered of him in the '90s, and of course on through the endless cameos of our present era.

Marvel really did employ cartoonists, because The Marvel Method demanded it. Art comics, scoffed at by mainstream devotees, often takes the idea of an artist writing and drawing their stories as proof of a higher use of the form (Dan Clowes, Julie Doucet, etc) than that used in most mainstream comics (penciller, inker, letterer, writer, editor). Marvel actually did adhere closer to the Doucet model than most large publishers, and I think this is why their books were so creative and popular. They were works of cartooning, a single artist's vision, and Lee is deeply important for setting this system up, a moment of wild creativity in mainstream publishing. Auteur cartooning, minus 10% (Lee’s copy).

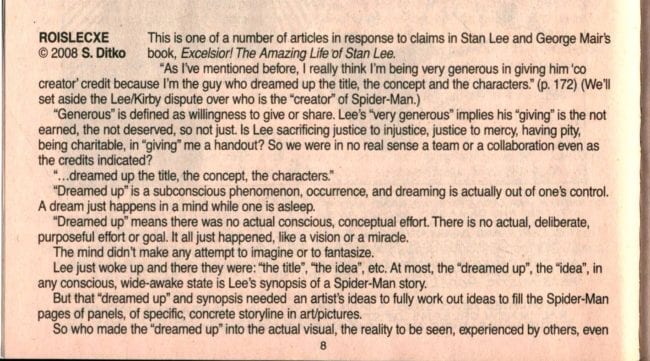

The other 90% took a lot of work. Ditko, in his Avenging Mind tract from 2008, said that Lee's explanation of how he created Spider-Man boiled down to 'I'm the guy who dreamed up the title, the concept and the characters.' The phrase 'dreamed up' catches Ditko's ire, precisely because it's so vague: about as vague as what happens in closed door meetings with an artist to talk about a story. In the absence of a hard copy script, we must refer to Wood's characterization of it all: 'We'd stare at each other until I came up with a storyline.' Ditko knows this is how these things went, and he knows the beauty of the title/concept/characters is in his cartooning arrangement of it. The non-effort of a 'dream' is too glaringly close to the non-effort of staring at an artist for Ditko to let is all pass without pages of analysis. He knows the implications of this turn of phrase too well.

3.

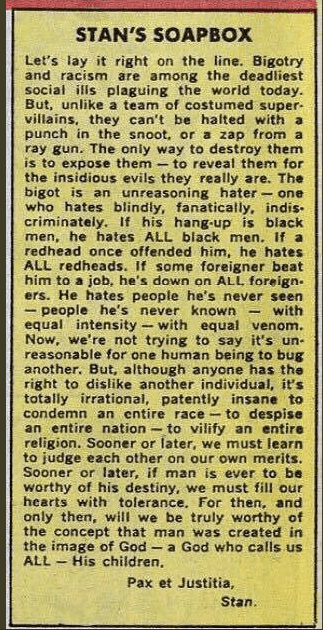

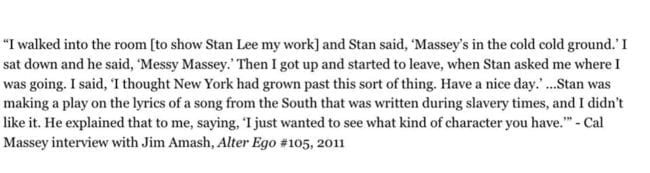

When Lee passed, I saw this image, a '60s era Stan's Soapbox editorial about the evils of racism, floating around the internet. I want to believe this is who Stan really was---and I think it probably was, mostly, or who he evolved into. But in the '50s, Lee subjected African American cartoonist Cal Massey to this kind of treatment:

Again, I believe that Lee grew beyond this type of behavior and stood for something else. But the unthinking coupling of Lee to deep progressive foresight when the reality is far more muddy speaks to the constant cloud of confusion around Lee: over and over, people accepted (and continue to accept) his simplistic statements on who he was and what he did. The soapbox statement is about as accurate a document of his core as the idea that telling Ayers ‘spurs shining and hoofs flashing’ qualifies as a creative act.

4.

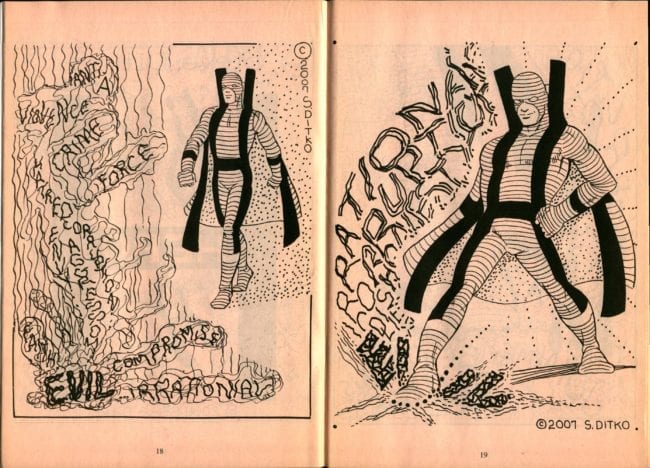

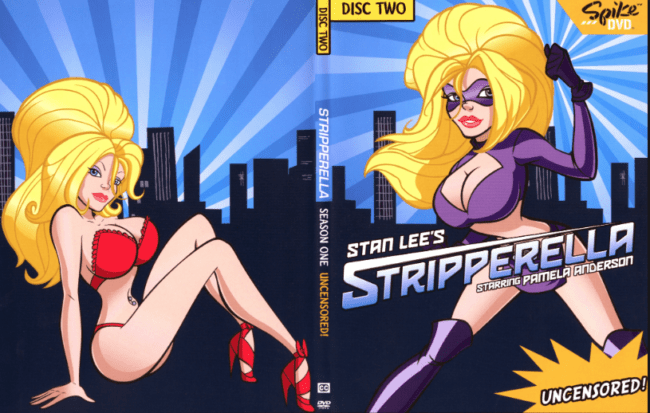

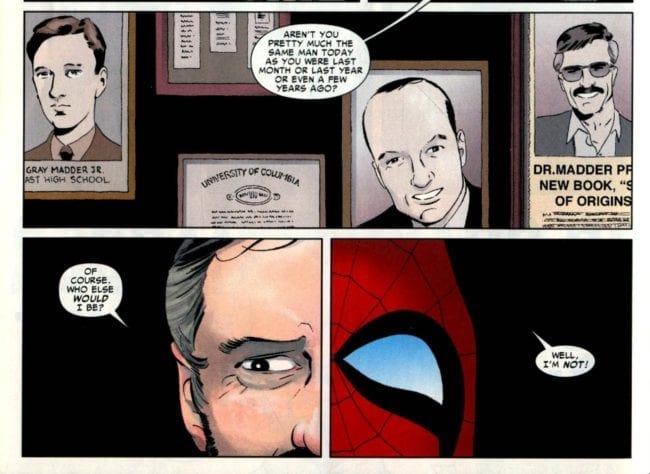

A spread from a Ditko story in 2007 provides a nightmare high contrast to what Lee was up to at roughly the same time.

Ditko was 80 years old when he drew those images, as was Lee when he did whatever it is he did with Stripperella. When you’re an artist, you can always create. All you need is time and space. When what you do is arrange talent around vague concepts, sometimes you show your hand.

If Lee’s legacy is a bizarre one, it’s a microcosm of the greater confusion surrounding the artistic credentials of cartooning. The personal, inverted work of people like Ditko feels a lot farther away from what comics have come to mean to the general public than the ham-fisted, loud, and often pure-shit of their more boisterous peers. We have Lee to thank for a lot of that.

5.

Dylan Williams once said that people had all these ideas, theories, and rumors about Ditko, but whatever the truth about him was, who could say how they’d deal with going through what he went through? At first, I thought Dylan meant, ‘How would you deal with something being taken away from you?’ As time goes on, I think Ditko’s struggle was more about being precise and thinking, thinking a hell of a lot about what went into one’s expression and what it could withstand, what it would say, while all the while having to be endlessly linked to someone who was very much the opposite.

Ditko’s tract of essays about comics, many of them about Lee, was called The Avenging Mind and the Scales of Justice. As long as the mind is on, right can be found and will be done, in Ditko’s view. If there is one assumption I’d hazard to make about an artist who hated assumptions, I’d say it’s that he formed much of his post-Spider-Man thought in reaction to Lee’s brazen meddling with facts.

Many people will say what Lee did wasn’t that bad (with one commenter on this site saying that they were hardly ‘war crimes,’ a high bar to hit!), that his gifts outweigh the crimes. I can agree that there are gifts, but when I look at the mark he left his artists with, I don’t have much sympathy. Ditko thought about his craft, he respected cartooning and elevated it as high as one person could. His work has few peers in any medium, in my heart and mind. Lee obscuring the fullness of Ditko’s art for his own benefit is a misstep for the form, a loss. It creates a misconception of cartooning on the public stage that the medium still hasn’t untangled.

In 2009, Lee wrote a back up story for The Amazing Spider-Man #600, with art by the great Marcos Martin. It’s a very charming twelve pages. Lee, as a psychiatrist, counsels Spidey about his many transformations and what it all ‘means.’ In Lee’s hand, the answer is ‘nothing much except a few cute jokes,’ which is fine. The story has a certain sadness hovering over it, which is never grasped at. Lee’s work, for all its bombast, doesn’t risk any real self-revelation. But then we come to the final page:

Owing to The Marvel Method, we can’t know if it was Martin or Lee who called for Stan to have his own psychiatrist resemble a caricature of an important figure in his (and Spidey’s) life: Ditko. Whoever made that choice adds a jarring moment of truth to the otherwise light affair, as Ditko’s prescription for his patient is blunt: THINK.