This past week saw the launch of Electricomics, a free digital comics reader for Apple tablets with ambitions toward becoming an open-source 'ecosystem' for digital comics development. To this end, a creator tool and code library will be distributed shortly; users can then publish their own comics in a unique file format (.elcx), which may be downloaded and read via the app itself. Funding was provided through the UK's Digital R&D Fund for the Arts, with development handled by Ocasta Studios and Orphans of the Storm, the former designers of media and lifestyle apps for entities like the Virgin Group, and the latter an arts group formed by the writer Alan Moore and the photographer Mitch Jenkins, collaborators on projects like the visual/audio album Unearthing and the short film series Show Pieces.

As it happens, Alan Moore has had his name attached to (and occasionally detached from) several well-known comics over the years, so this launch comes with a bit more promotional heft than the average e-reader - fulsome pieces have appeared at Wired and the Guardian. Further sweetening the deal is the app's lineup of pre-loaded comics, which amount to a complimentary anthology of original work from quite a few veterans of print and digital; the editor is Leah Moore, a scriptwriter for venues like 2000 AD and co-creator of Channel 4's episodic online comic The Thrill Electric, who also serves as a project manager for Electricomics and the platform's public face. Other familiar names crop up around the margins - oft-awarded letterer Todd Klein is responsible for logo designs throughout the app, while the project's research team (headed by one Alison Gazzard) includes Daniel Merlin Goodbrey, a proponent of experimental webcomics going back more than a decade.

And indeed, the four stories included with the Electricomics app can be considered experiments, or perhaps tech demos - each appears to have been designed to embody a different style of narrative, showing off the features of this platform. I will now discuss each of these comics/demonstrations, in rising order of complexity.

--

Red Horse

Written by Garth Ennis

Digitally painted by Frank Victoria

Lettered by Erica Schultz

We begin with something very basic and readily accessible: the long vertical scroll, an "infinite canvass" technique familiar to any among the legion which enjoyed Gilles "Boulet" Roussel's The Long Journey a few years back. There are no clicks or page-turns - only a gradual descent into the morass of warfare, as is often the destination in Garth Ennis scripts. Indeed, despite its presence on a notionally forward-looking digital platform, what's most interesting about Red Horse is the ease with which a formally unadventurous piece translates to a webcomicsesque format.

From what I can gather, individual creators have approached the Electricomics platform itself with varying degrees of engagement; there is an Andy Bloor credited universally in the app for "design and art preparation", and a Craig Scheuer credited for "art preparation, colour flatting", so perhaps they bore some responsibility for the digital conception. Alan Moore has stated that Ennis had very little to do with the production beyond supplying a script, which I will guess probably did not specify any page layouts; what appears in the app, however, is the not-unfamiliar print comics device of stacking 'wide' panels, a la Moore's current serial Providence. In fact, Leah Moore states in the About section of the app itself that the featured comics were no more than eight "pages" each, implying that the work was conceived as eight (or so) print pages' worth of stacked tiers, which were then (in effect) pasted together to form a single unit; just the other week I highlighted an artist, GG, who has produced similar all-wide comics in alternate print and digital forms.

The technique works pretty well; Ennis doles out large blocks of epistolary narration, positioned with ease inside artist Frank Victoria's uncluttered frames. It's historical fiction, concerning a very young cavalryman's excited witness of Charles Beck Hornby's 1914 felling of the first German of World War I on Britain's behalf. The theme is a very old, even classical Great War trope: the excitement for a quick and gallant victory on the precipice of bloody modern massacre. Yet as on-the-nose as young Tom's historically ironic recount might read -- "I want an honest, decent combat, one gentleman against another.... Now that I've had a taste it really seems all the more wonderful." -- it functions adeptly enough as youthful boasting, which Victoria undercuts through ominous rust-drenched flashbacks. Soon the fuller color of day will illuminate the Battle of Mons, where fantasy and fantasist may yet be among the thousands killed.

--

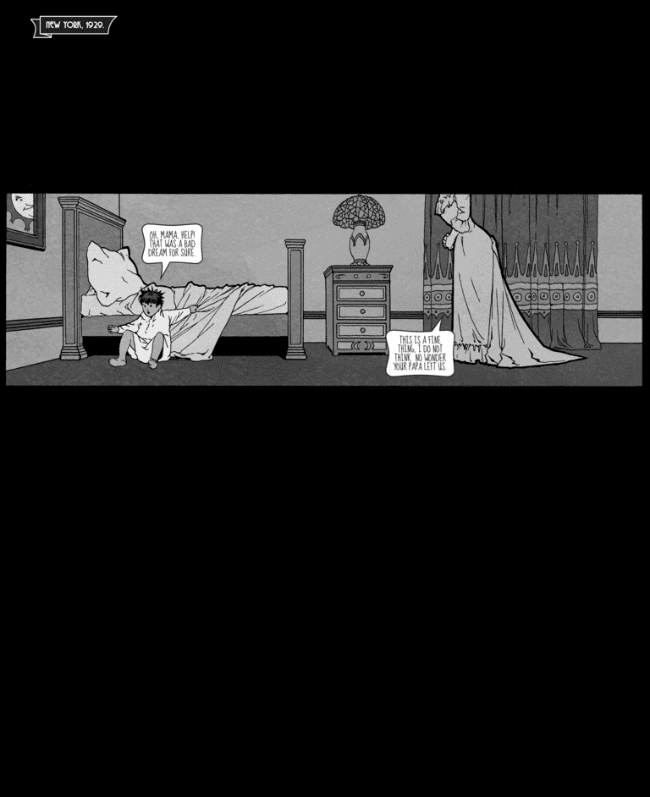

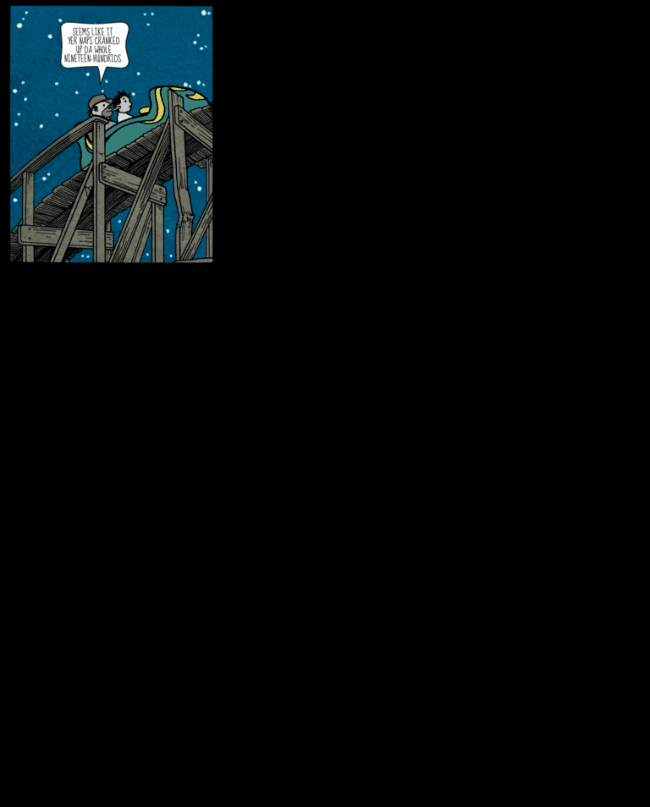

Big Nemo

Written by Alan Moore

Drawn by Colleen Doran

Colored by José Villarrubia

Lettered by Erica Schultz

Animated by Giulia Alfonsi & Sean Gannon

I was delighted to realize that two of the four Electricomics pre-loads -- half the fucking anthology! -- are concerned with romantic fancies papering over the hell of life's circumstances; quite the irreverent stance for an idealistic new 'ecosystem'! But that sort of welcome skepticism is practically a British comics tradition, and Alan Moore can grimace with the very best. Longtime readers will recall a throwaway gag involving an off-panel Not-So-Little Nemo suffering a very adult nightmare from his tenement slum bed in 1986's In Pictopia!, and Big Nemo serves to carry this device of the telling grownup dream into a sweeping historical comment of its own. To wit: the Land of Wonderful Dreams as delineated by Winsor McCay embodied the cocksure vigor of a nation emerging from the 19th century toward a seemingly limitless horizon of heroic destiny, one which would not be individually fulfilled in the many lives of grown adults coping with Depression and war. If you recall Moore's writing on American science fiction years ago in Dodgem Logic magazine, much the same impulse was attributed (albeit with a far more boorish connotation) to Edward Stratemeyer's Tom Swift, which similarly knew praxis via the 2013 graphic novel Nemo: Heart of Ice.

What I am saying is that this is pretty well-trodden ground for an Alan Moore comic script. However, there are several interesting complications to the final comic which enliven the whole.

Winsor McCay does not need Alan Moore to darken his work. While the fanciful elements of Little Nemo in Slumberland have perhaps gone a ways toward caricaturing McCay's body of work, his humor often leans toward the rueful. What is Little Sammy Sneeze other than a gag comic built around the frailty of daily existence? Personally, I am partial toward McCay's short-lived The Story of Hungry Henrietta, a serial about a growing girl whose parents' inattentive indulgence begets an insatiable desire to consume everything around her; it's both funny and sad, and sometimes even chilling. And Big Nemo knows damn well that McCay is capable of this - not only for throwing in a "dull care" joke in reference to A Pilgrim's Progress by Mister Bunion, but in its very makeup as a digital comic, which primarily evokes the panic expanses of Dream of the Rarebit Fiend.

You do not scroll or flip through Big Nemo. This is a guided experience, where you need only tap on the right side of the screen to advance the action. Step by step, panels fill the page; often, one element of succeeding panels remains fixed while other elements 'animate' - a very common trick by which McCay would manifest scary deviations from reality. Big Nemo takes this is a more cerebral direction, jostling its boy wanderer through layers of personal history and childhood fantasy, and pitting elements of McCay's body of work against one another: the superficiality of the text is that of whimsical dreams, yet its grammar is formed of nightmares. And what gives a Winsor McCay character nightmares?

Overindulgence.

The criticism is within the source itself!

The same might be said for Big Nemo. Tapping through a comic image by image -- building pages, piece by piece -- can't help but evoke McCay's place as a pioneer of animated films. Stripped of deliberate sequence, as in the bottom image above, the layouts sometimes more resemble those of Frank King, who would populate each frame of a fenced splash with different moments in time for a wistful effect; these pages need mobility to convey McCay's very presence. There is even a little in-panel animation, moving by itself without the reader's input, but this animation is only like McCay's in its looping of frames, with nothing in the way of rotation or scaling, let alone the artist's communication of bodily gesture, or the flashes of uninhibited activity that marked the voluptuous plumes of smoke and flame in even as somber a work as The Sinking of the Lusitania. If this is the start of something new, continues the metaphor, it is considerably more tenuous than McCay's own extravagant experiments.

Nonetheless, the work is what it needs to be. Colleen Doran's art is still, studied, and I think quite chilly, but she is not drawing a simple homage; rather, her work stands very appropriately in this context as a windswept memorial. By the end, her and Moore and all the rest are evoking McCay's own latter career as a dedicated craftsman of monumental editorial illustrations with the image of a mighty golden statue, which transitions in a touch to that of a fleshy man lying in bed, José Villarrubia's colors at their most watery and tainted. If Red Horse showed that basic comics could function in just as accessible a way in a native digital format, Big Nemo does yeoman's work in enlivening simplicity through a digital approach freighted enough with allusion you might fear the whole enterprise was concocted simply for it.

--

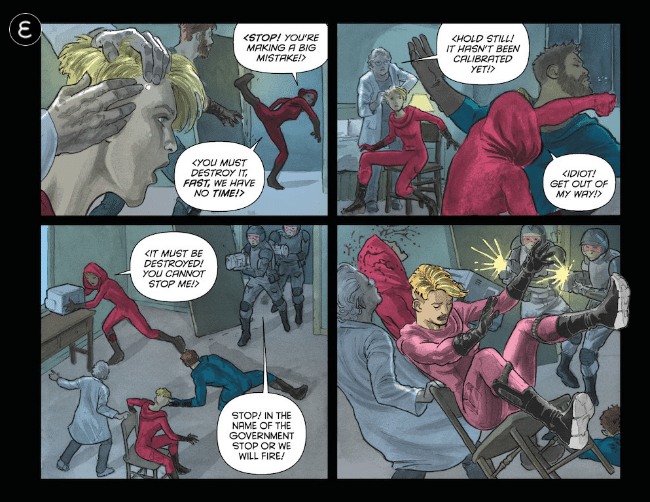

Sway

Written by Leah Moore & John Reppion

Drawn by Nicola Scott

Colored by José Villarrubia

Lettered by Simon Bowland

Animated by Giulia Alfonsi

Sway is a more direct experiment in posting a technical attribute as a narrative actor, but here the limitations of either the technology or its early usage lead the project into trouble.

On first glance, the story is an extraordinarily simple four-page affair in landscape-format pages navigated by finger swipes (the Electricomics app automatically orients stories in landscape or portrait format, though the portrait-native stories can be somewhat touchily reoriented into landscape; the landscape-native stories appear to be locked in that position). An black tech implant is being inserted into a woman's head when a hooded figure bursts onto the scene, intent on destroying the chip. The police follow, guns blazing, and the woman is killed. Nearby agents of "Sway", late to the scene, lament having somehow pursued this woman to her death, despite the fact that she didn't appear to be running from anything. THE END.

If you have been a good reader, though, and paid attention to the informative About Comic section on the app before starting, you know that at certain points in the story an icon will appear in the upper left corner of the screen, urging you to physically tilt your device, and thereby triggering an animation of the chip-implanted character falling out of the comic's panels and into a new and different page of comics set ages in the past.

The image of falling into and out of comics as a metaphor for time travel is very potent; unfortunately, it is also a metaphor that does not flatter the execution of Sway. Immediately upon landing in timeline 2 (of an eventual 3), I swiped left so as to pull the next page, the next frame of spacetime, from the right. Then, I went back to the sway point and tilted my iPad again; I was deposited back in timeline 1. Very good. Then, I tilted again to return to timeline 2, and began swiping right, pulling prior panels from the left, wondering what would happen if I kept pulling 'prior' frames from that period of time before the implanted character had arrived. Would I see activity in the room before she dropped in? I was hoping for a small model of the universe, not unlimited (obviously), but with frames running parallel at perhaps the same length as timeline 1...

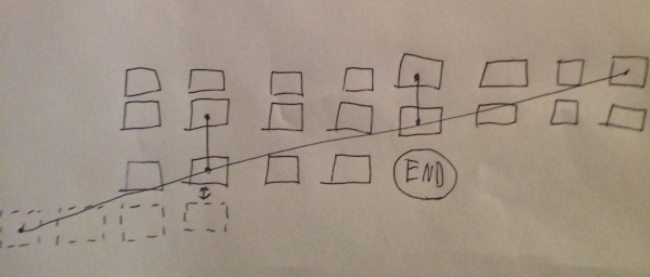

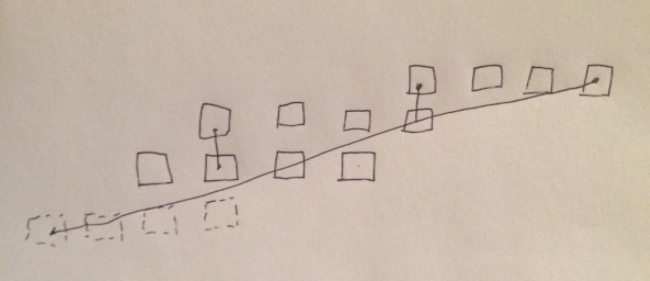

You know what? Let me court ridicule by drawing a chart.

Above is timeline 1, alpha version, i.e. the four pages you see without swaying through timelines.

Now here is what I'd expected of the scale model - three timelines, navigable from left to right and vice versa, with discreet sway points; at the end of timeline 3 (the one up top) there's a sway point which transports you to alternate scenes from timeline 1 which are otherwise inaccessible, so I've drawn them under timeline one as dotted lines.

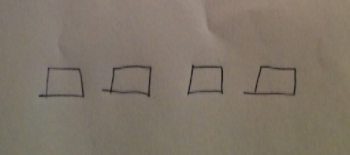

As it turned out, my model was inaccurate. Attempting to navigate left from the sway point at the front of timeline two just took me back to the sway point in timeline 1, regardless of whether I tilted my screen or not. Here, then, is a more accurate chart of the comic:

Sway, despite its multi-dimensional pretense, is extremely linear. Not only can you not go backward past the first sway point in any timeline save for the first, you actually don't need to tilt the device at any of the subsequent (rightmost) sway points; you can just keep whipping panels out from stage right and the implanted heroine will simply jump from timeline to timeline on her own, although you will miss some inessential unique pages that only appear if you physically sway. This chart represents a 'full' sway, and you can see there are sixteen frames in total (you see the last two in timeline 1 after you pass the dotted line alternates, provided you didn't skip the first sway and wind up with a four-frame comic) - stack them in twos, as the old bande dessinée publishers used to do with serial strips, and you've got the obligatory eight pages.

I am very much aware that the version of the comic I'd felt was suggested by the project's central narrative device would involve a great deal more in the way of time-consuming labor than was probably viable given the busy professionals involved, on the schedule necessitated by grant funding. Still, it's all somewhat dispiriting in its simplicity; the script by editor Leah Moore and longtime writing partner John Reppion, when fully revealed, is basically a 'Time Twister' in the tradition of 2000 AD (to which the writing team contributes), with the agents of the eponymous Sway pursuing their target -- who, inadvertently or not, seems to be threatening the very circumstances that brought about the agency's existence -- into a chronological loop that seals her doom. As a reader, I felt restricted to a fated path as well, and not to any deeper meaning. The tilting itself is still fun, as is action comics specialist Nicola Scott's limbs-akimbo art, but the piece's efforts at formal-thematic cleverness gesture painfully toward ambitions it cannot fulfill; in this way, it has the most purely experimental feel of the four pieces, as it delivers results that will hopefully be useful as a foundation for developments later in our own timeline.

--

Cabaret Amygdala Presents: Second Sight

Written by Peter Hogan

Drawn by Paul Davidson

Colored by José Villarrubia

Lettered by Simon Bowland

Animated by Giulia Alfonsi & Sean Gannon

Finally -- perhaps inevitably -- we arrive at the comic-as-game; the aforementioned Electricomics lead researcher Alison Gazzard, in fact, has a doctorate in video game theory. Writer Peter Hogan, for his part, has mentioned jigsaw puzzles as an inspiration, though he is careful also to disclaim any game design role, having purportedly left the details of implementing his narrative suggestions to "the technical guys" - it could be Andy Bloor and/or Craig Scheuer, as mentioned above. Regardless: "To navigate this comic you will need to look for clues and hints to progress." So states the now-sinister About Comic section of the app.

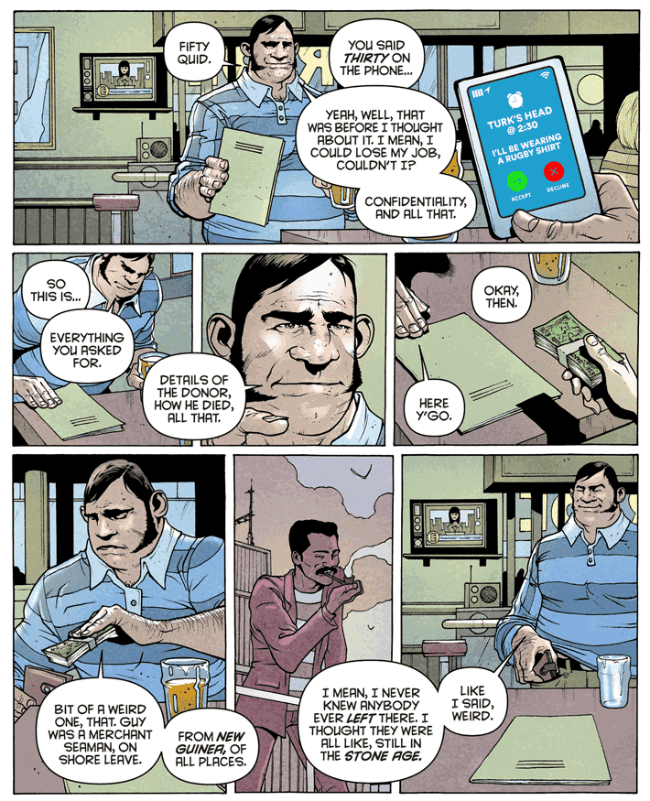

In practice, Second Sight calls to my mind a similarly gamified digital comic - Emily Carroll's Margot's Room (2011), which presents the reader with a hub screen on which they can click various objects to take them to story chapters relating to those objects. There is a lot of leeway granted to the reader, which can easily be misused; above the hub screen is a poem suggesting the means of accessing a chronological reading order, though random clicking can instantly drop the reader into the story's finale, which depends on the context of chronologically earlier chapters for its impact.

Second Sight is a far more guided experience. As in Big Nemo, the reader taps the screen to navigate, though they cannot navigate back and forth, and full-screen images are presented in their entirety, rather than gradually; soon, the reader is left in a doctor's office, elliptically discussing a weird case. But look: through the magic of animation, your phone is ringing in the last panel!

Tapping to answer then whisks you away to a new screen (note the phone up top):

Several items are now animated on this page, and tapping one of those items takes you to another new page. You then use items to move back and forth between screens, reading or re-reading case information until you have looked at every possibility. I presume there is something in the programming to flag which items you've checked, since after you've hit them all you're automatically taken to a completely new screen:

Automatic, but also abrupt. The first time I saw this screen above I had no idea what I'd done, or how it connected to my just-ended item search; putting the items somewhere in the first panel could have easily connected this expository eruption to what had gone before. This also marks the end of the story's non-linearity, as well as its interactivity, save for a memorably gross opportunity to manipulate a gigantic close-up of an eyeball with your fingers. But even this interactivity is poorly indicated; it's very easy to miss, almost like an Easter egg, except the information therein is required to make any sense of the plot, redolent with cannibal flesh-eaters and inherited violent tendencies reminiscent of Italian horror cinema.

Unlike Sway, this comic does not overstep its narrative-thematic bounds -- there is a lot of pertinent and funny business regarding eyes, ranging from textual puns to shifts in and out of first-person perspective -- but it does seem awfully unpolished. One of the final images is a full-on repeat of a whole page from the beginning of the story, to no apparent narrative purpose; was this somehow necessary from a technical perspective? One presumes some of the mystery will fade once the development kit is released, and the contours of what is possible can be better explored. The work that exists, though, is the work that exists, and for now Electricomics communicates an unsurprising state of digital comics in which works succeed the most when sticking to what their creators already know best.

***

PLEASE NOTE: What follows is not a series of capsule reviews but an annotated selection of items listed by Diamond Comic Distributors for release to comic book retailers in North America on the particular Wednesday identified in the column title above. Be aware that some of these comics may be published by Fantagraphics Books, the entity which also administers the posting of this column. Not every listed item will necessarily arrive at every comic book retailer, in that some items may be delayed and ordered quantities will vary. I have in all likelihood not read any of the comics listed below, in that they are not yet released as of the writing of this column, nor will I necessarily read or purchase every item identified; THIS WEEK IN COMICS! reflects only what I find to be potentially interesting.

***

SPOTLIGHT PICKS!

The Dharma Punks: Conundrum Press brings this 6" x 8.25", 416-page collection of a very successful 2001-03 New Zealand comic book serial from Ant Sang, politically aware and spiritually inclined. A prior iteration of this collection was funded via Kickstarter after the work spent a decade out of print, and now it sees international distribution to the curious. Introduction by Dylan Horrocks. Samples; $25.00.

Terror Assaulter: O.M.W.O.T. (One Man War On Terror): Being the latest release from Benjamin Marra, a 112-page collection/massive expansion on a 2014 risograph comic book from Colour Code Printing. I liked that riso - Marra plumbs deeper-than-ever dimensions in funnybook eccentricity by positing a world in which people react to virtually anything with affectless present-tense declarations of exactly what is happening, and terrorism is destroyed forever in the process. This newer, bigger book is from Fantagraphics, and artist Josh Bayer wrote an interesting review the other day, comparing the hero to Harpo Marx and discussing "schizoid culture" literalism; $14.99.

--

PLUS!

Honor Girl: Being the graphic novel debut of Rookie contributor Maggie Thrash, a 272-page color memoir of teenage queer awakening at summer camp. Candlewick Press publishes in hardcover - comics pros like Ariel Schrag and comics-friendly types like Ira Glass have already noted their support. Your YA pick of the week for sure. Interview & samples; $19.99.

The Michael Moorcock Library Vol. 2 - Elric: The Sailor on the Seas of Fate: Continuing Titan Comics' hardcover reprint series of Moorcock adaptations, still focused on First Comics fare I'd completely forgotten about until this effort began. I'm guessing this 216-page tome will collect the entirety of a 1985-86 miniseries of the same subtitle, adapted by Roy Thomas with art from Michael T. Gilbert & George Freeman; $29.99.

Judge Dredd: The Complete Case Files Vol. 1 - 10th Anniversary Special Edition (&) Judge Dredd: The Complete Case Files Vol. 25: My god, we've started commemorating the history of reprints with reprints of reprints. I can't say that Rebellion's early Judge Dredd phonebooks couldn't use an update, though - at the very least they lacked any color reproduction, which this 336-page hardcover will now add, along with what I think should be improved paper quality. Really early Dredd is far from the best Dredd, but there's a certain appeal to tenuous beginnings when a strip's been going for this long. Meanwhile, the main line of reprints reaches a nice milestone number, as mid-'90s stories relating to writer/co-creator John Wagner's The Pit cycle wrap up and other scriptwriters step up, including the always-interesting John Smith via Darkside, a 72-page serial with frequent collaborator Paul Marshall; $51.99 (vol. 1), $29.99 (vol. 25).

Walt Disney's Donald Duck: The Golden Helmet (&) EC Archives: Two-Fisted Tales Vol. 1: Two presentations of mid-century titans in accessible formats. The Golden Helmet is part of Fantagraphics' line of reformatted 7.25" x 5.5" duck books, showcasing shorter and longer works by Carl Barks; this one is 128 pages. Two-Fisted Tales continues Dark Horse's color packaging of Entertaining Comics with the first six issues of the Harvey Kurtzman-fronted combat series, totaling 216 pages. Two-Fisted samples; $12.99 (Duck), $49.99 (Tales).

Leonard Starr's Mary Perkins, On Stage Vol. 14 (of 15): A special commendation on this busiest of reprint weeks goes to Classic Comics Press on reaching the penultimate volume of this newspaper drama collection, the first since creator Starr died this past June. Note that the page count has increased to 310 to accommodate a runoff of strips not extensive enough to warrant a sixteenth volume; $25.95.

Hogan's Alley #20: And we'll close with mention of this very long-running magazine (since 1994!) on the topic of vintage comics and cartoons. Strip man Patrick McDonnell is the feature interview, while other articles promise a look at Believe It or Not knockoffs and a chat with John Dirks, son of The Katzenjammer Kids creator Rudolph Dirks. Innumerable sample comics; $6.95.