Although the adventurous soap opera strip had begun with Mary Worth in the late 1930s, it was in the late 1950s that Leonard Starr created the best-drawn and the best-written one with his Mary Perkins, On Stage.

He became a professional cartoonist while still a teenager. When he, in 1942, began working in the field, the industry was still expanding and Superman was just four years old. A native of New York City, where most of the comic book action was, he broke in by drawing for two of the pioneering art shops. The first was that run by Harry “A” Chesler, known to his employees as Harry “A” Chiseler. The other was Funnies, Inc. a much more reliable outfit. It was run by Lloyd Jacquet and Bill Everett was the art director.

This shop provided art and editorial for, among several publishers, Martin Goodman’s Timely line. Starr assisted on such heroes as The Human Torch and The Sub-Mariner. He had, as had several other young men who became comic book artists, studied at the High School of Music and Art in New York and the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. Eventually dissatisfied with the quality of the stuff he was turning out, he enrolled in the Art Students League in Manhattan.

Throughout the '40s he sold to a wide range of publishers, large and small. Among the main titles his work appeared in were Red Circle, Liberty Comics, Airboy, Young Romance (for Joe Simon & Jack Kirby), Adventures in the Unknown, and Crown Comics. He teamed up with Frank Bolle on some of these jobs and for Crown they had a feature about a tough private eye and one about a mystic jungleman.

Starr had early fallen under the spell of Milton Caniff and he developed a modified style that was much influenced by his studying Terry and The Pirates. As the '50s began, Starr added DC to his list of clients and started appearing in such titles as Tomahawk, Gang Busters, and Detective Comics. For ACG he did stories for Adventures in the Unknown, Operation Peril, and Soldiers of Fortune. His drawing had a vitality and gave the impression he was enjoying himself and having fun. His women characters, whether femmes fatale or damsels in distress, were increasingly attractive and indicated what one of his strong suits would be when he graduated to a comic strip of his own.

It was the ambition of many comic book artists to move up to a newspaper strip and several of his contemporaries had made the transition, among them Ken Ernst, Stan Drake and Dan Barry. Finally in 1957, after several earlier strip submissions to syndicates, he sold Mary Perkins, On Stage to the Chicago Tribune-New York News Syndicate. The title of the strip alludes to two of the most popular radio soap operas of the time—Mary Noble, Backstage Wife and Ma Perkins. Starr had long been a theater buff and the new strip would deal with “the glamorous New York theater world.”

His style had changed, moving toward what has been called photographic realism. He was influenced by what Alex Raymond had done on Rip Kirby and what Dan Barry had done on the daily Flash Gordon in the early 1950s. Starr has been called “a man with a superlative ink line.” His staging of the events in the life of Mary Perkins as she conquers Broadway, TV, and the movies and finds love is very good and he alternated light continuities with some dark and unsettling ones. The National Cartoonist Society gave him the Best Story Strip Award in 1960 for On Stage and in 1965 a Reuben as Outstanding Cartoonist of the Year.

By the 1970s story strips were declining in popularity and funny stuff was multiplying. On Stage held on longer than many but was losing papers and in 1979 the syndicate decided to cancel the strip. By the end of the year, however, Leonard Starr was back in the funny papers drawing Annie, an updated and modified version of that plucky put-upon waif Little Orphan Annie. He said the title had been shorted to Annie to make if seem less dated and to refer to the highly successful Broadway musical.” He did Annie in a more cartoony style than he’d used with Mary Perkins and, in as a tip of the hat to creator Harold Gray, his Annie had blank eyeballs. It was a handsome job and a good looking strip. Starr retired in 2000 and Annie held on until of June of 2010.

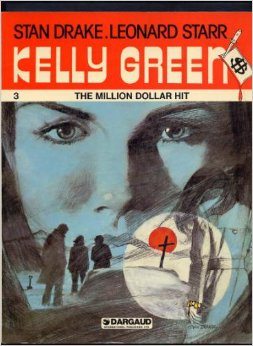

The modern graphic novel began appearing in the United States in the middle '70s. Among the earliest titles were James Steranko’s Red Tide in 1976 and Will Eisner’s A Contract With God in 1978. Europe had been using the format for decades, calling the books graphic albums, notably with Herge’s Tintin series. A great many of the hundreds of albums later published, such as Jean Giraud’s Lt. Blueberry titles, were not aimed at children and had adult content. In the early 1980s, Leonard Starr entered into the adult graphic novel field as a writer. He teamed up with Stan Drake (The Heart of Juliet Jones), who did the drawing. Both men were well known for work showcasing beautiful women. The star of the five graphic novels that they went on to do for French publisher Dargaud Editeur was pretty red-haired woman named Kelly Green.

Starr and Drake were sharing a studio on the Post Road in Westport. It was on the second floor, always smoke-filled, and on the same block at that time were a movie theater and an art supply store where both had charge accounts.

The Kelly Green books were in trade paperback format and followed the adventures of their heroine in Europe working as a go-between, somebody who delivered the ransom money to kidnappers or arranged for the return of a valuable object. This being the '80s, Kelly had “big hair” in the manner of Farrah Fawcett and, this being France, she now and then appeared naked and, more often, in her underwear. Drake did some of his best work on this feature and Kelly was quite a bit more interesting than Juliet Jones. The stories were action-packed, violent and in the mold of foreign intrigue movies in the James Bond mode. Four of the books were reprinted in English translation in America. The fifth will be included in an omnibus volume coming out later this year in the United States.

The Kelly Green books were in trade paperback format and followed the adventures of their heroine in Europe working as a go-between, somebody who delivered the ransom money to kidnappers or arranged for the return of a valuable object. This being the '80s, Kelly had “big hair” in the manner of Farrah Fawcett and, this being France, she now and then appeared naked and, more often, in her underwear. Drake did some of his best work on this feature and Kelly was quite a bit more interesting than Juliet Jones. The stories were action-packed, violent and in the mold of foreign intrigue movies in the James Bond mode. Four of the books were reprinted in English translation in America. The fifth will be included in an omnibus volume coming out later this year in the United States.

As Rankin/Bass, Jules Bass and Arthur Rankin had been producing successful animated cartoon specials since 1960, such perennial seasonal shows as Frosty the Snowman and Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer and series like The Jackson Five. In 1985, Jules Bass contacted Leonard Starr, who done some scripts for them, with a proposition. They needed some immediate help on a property they’d acquired. It was a sort of swords-and-sorcery sci-fi fantasy idea for a show about humanoid catpeople with such names as Lion-O, Cheetera, Tygra, etc. Could he, in a hurry, develop it into something workable? He could. Working from a list of the characters and proposed settings, plus an attractive ThunderCats logo, Starr worked out all the basics and some sample story lines.

Bass was pleased but it’s somewhat unclear what the initial deal was. Starr was to get an on screen credit as the Developer and another as Head Writer. The Developer credit never showed up, though. The show as an almost immediate hit and went out to thrive for four seasons. It inspired all sorts of lucrative merchandising. The problem was that Starr didn’t get a share of the profits and finally had to bring a lawsuit.

In the startup days, he invited in a group of writers to work on scripts. They included Howie Post, William Overgard, Rick Marshall, and me (Starr and Gil Kane had been friends since their teenage comic book days and, as I recall, I met Starr through Gil). I sat in on a couple of writers meetings in the R/B Manhattan offices and initially wrote three scripts for some of the earliest shows. Bass, for some reason accepted two and rejected the other one and told Leonard not to buy any further scripts from me.

A bit later, Leonard hired me to work with him at his Westport home. We came up with ThunderCats ideas and I wrote the scripts. He submitted them as by himself and then paid me. I don’t remember why the deal eventually ended but it was fun while it lasted. I invented a pirate character named Ironfist who later became a toy. I do remember that Leonard was one of the most amiable writers I ever worked with.