A conversation with James Romberger

Ralph Reese’s career began in the 1960s as a 16 year old assistant at Wallace Wood’s studio. His earliest works including pieces in Wood’s experimental prozine Witzend reflect his mentor’s influence, but his own unique abilities quickly became obvious. An intuitive graphic storyteller and accomplished draftsman, he affords every subject a solid, visceral tactility---the reader can believe what they are seeing.

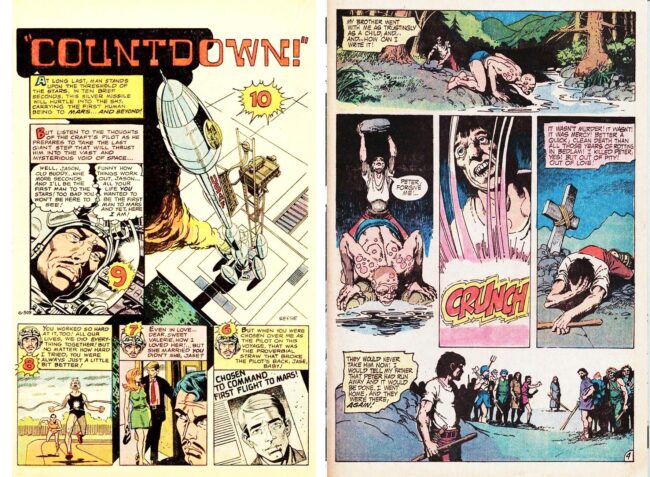

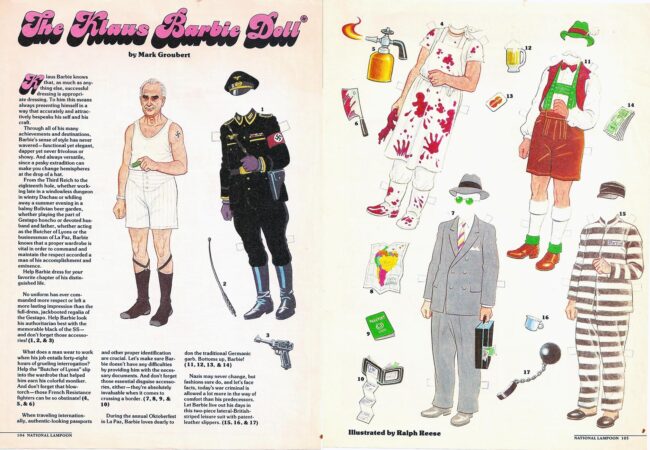

He may be best known for his work in the slick collegiate humor magazine National Lampoon. I’ll always remember a truly awful comic done with his friend Larry Hama there, about a terminally-ill child whose last wish is to attend to the Ice Capades---it is an apotheosis of banality. Ralph “only” inked it, but he still somehow dominates the piece. His precision makes these sorts of underbelly-of-America subjects very tangible, as his textured inking also gives things a countercultural, undergroundy vibe.

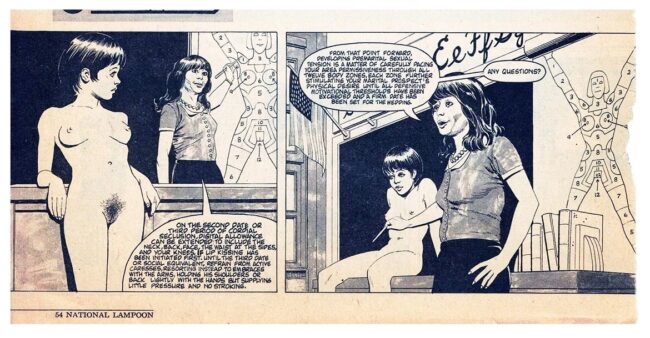

In the Funny Pages at the Lampoon, he and Byron Preiss collaborated on THE white middle class romance comic of the 1970s, “One Year Affair,” which ran as a serial and then was collected into a trade paperback in 1976. With that, Reese and Preiss could lay claim to having made two of the earliest American mass market graphic novels, the other being their Sherlock Holmes: The Woman in Red, one of Preiss’s Fiction Illustrated series of bookstore-distributed long-form comics that also included Steranko’s Chandler: Red Tide.

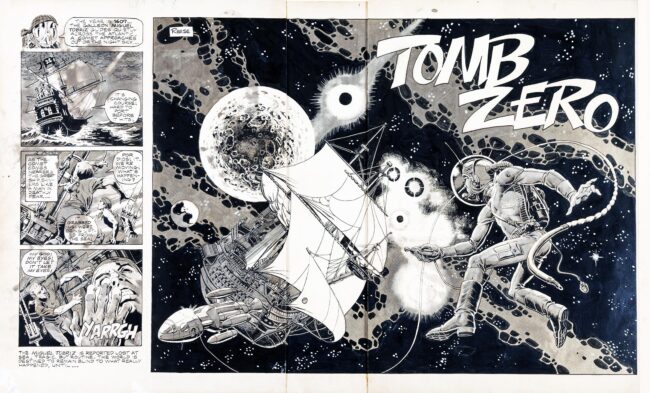

Reese’s talent and dedication have taken him through to working for quite an array of publishers: comics for DC, Marvel, Warren, Skywald, Tower, Pacific, Eclipse, Valiant, King Features and more, and illustrations for the likes of Topps, Children’s Television Workshop and Esquire. I “met” the artist via Facebook, where he posts his luminous commissions and reacts to the issues of the day. This interview was conducted by email over most of 2020.

Click on images to enlarge.

____________________________________________________________

JAMES: This interview is headed by a great photograph of you from 1966.

RALPH: Pretty sure it was taken by Wood in my pre-hippie days when I was still trying to look gangster…skinny ties and sharkskin suits…I woulda been about seventeen.

JAMES: You have already been interviewed at length about your time with Wood, so I think we should go for your subsequent career in comics. Am I right that you moved in the late 60s or early 70s from Wood's uptown NYC studio, to live downtown in the funky East Village? ---which is my stomping grounds, but I got there in 1981. By my time, it was crazy and fun, but also quite impoverished and an open drug supermarket. We had a great art scene in the middle of all that, which was ended by landlord greed and AIDS. Now it is all gentrified. Can you describe what it was like when you were there?

Ralph: I lived on E.7th Street between A and B, right across from the park. This would have been 1970-71 when I was married to my first wife and just starting out on my own. It was a very tempestuous relationship and we split up and got back together a couple of times, before finally getting divorced in I think 72. Joan was a radical feminist and a real Mao-spouting communist who went to Cuba with the Venceramos brigade, which earned us a visit from the FBI....we were desperately poor and the neighborhood at that time was quite sketchy. You really had to be careful, especially walking around at night. I got mugged a couple times at knife or gun point. Every Sunday early in the morning the conga drums would start beating in Tompkins Square Park and go on all day. The Odessa had the world's worst coffee. At that time a lot of the underground comics guys had come to NY and were working at Gothic Blimp Works etc. so we had a little scene going and we saw some great concerts at the Fillmore East. I was mostly working at Web of Horror and Galaxy and dropping acid now and then. It was a crazy time.

JAMES: One still had to watch one’s back and they were still drumming in the park when I got there a decade later. I actually miss the drumming, but I lived a few blocks away---you were right on top of it! Who in the East Village underground Gothic Blimp Works scene were you friends with? Did you know Kim Deitch? Bodē? Spain?

RALPH: I knew Roger Brand for a while because he came to work at Wood's studio in the late 60x before the NY underground comic scene really got going too much. So I was already friendly with him and Mchele. When Wood was still hanging out with Flo Steinberg we would sometimes visit with the Brands at their E. Village pad. Kim Deitch and Trina arrived here a bit later and by that time I was living on E. 7th St. with my first wife. Kim and Trina had a little storefront around 10th and A where she sold some hippie clothes and they lived in the back. Trina was a great admirer of Wood so I had met her before when she came to visit his studio. So I would drop by there once in a while. Then I started doing a few little things for Gothic Blimp Works and met Spain up there at EVO offices. He was quite pleasant and friendly and also a great Wood fan. The only time I ever met Crumb was when he had come to NY a couple years before and came up to Wood's studio to pay homage/interview him. He was very quiet and reserved and kept scribbling in his sketchbook, took no notice of me at all....

I only met Vaughn a couple years later when he was working for Lampoon and doing his Cheech Wizard shows. He came up to Continuity a couple times. I found him a bit... theatrical. I never really got to know him.

JAMES: Ok, later you worked at Neal Adams and Dick Giordano’s Continuity studios.

RALPH: Yes, I rented desk space from at Continuity starting in 1973. Larry Hama and I went down there together. We had been pretty much partners for a while after he got out of the Army and had been working out of my apartment. We thought that it would be good for self-discipline to have an actual workplace outside the home. Larry and I were in fact the first people to rent space there. Alan Kupperberg and Steve Mitchell were already there, but they were Neal's and Dick's assistants and didn't pay rent.

JAMES: Did Adams get work for you and other artists, subcontracting or functioning as a sort of agent?

RALPH: Neal was always doing storyboards and stuff for advertising and we were able to basically work off our rent in a day or two by helping him out with that. Neal did occasionally refer us to outside clients when there was a job he didn't want to do himself and he never asked for anything. Mostly at Daniel and Charles ad agency where we would crank out storyboards for twenty bucks an hour, which was fairly good money then. He also referred me to Young and Rubicam one time when they were looking for a full time "sketch man" or comp/storyboard artist. In those early days Neal actually helped out a lot of people. He would cash your Marvel checks for you if you couldn't afford to wait three or four days for them to clear your bank.

JAMES: Was it salaried, or paid as individual freelance jobs?

RALPH: No one got a salary, it was always totally freelance. We sat in the same room for about a million hours working side by side, so of course we talked a lot.

JAMES: Did Neal act as a mentor for you, or take a lot of personal time working or talking with you?

RALPH: Neal was never a teacher the way Wally Wood was. Most of what I learned from him I picked up by osmosis. Once in while he would make a suggestion but he wasn't above putting you down to show how superior he was either. He was always an egomaniac, but in the early days he kinda made up for it by doing good deeds.

JAMES: How did the Crusty Bunkers inking jams come about? Was this mainly something that happened if someone had a tight deadline?

RALPH: As far as I know, the Crusty Bunkers projects were all Marvel stuff. I guess if they got jammed up and needed an inker in a hurry, they would send the stuff over to Neal and he would kind of supervise, do some of the stuff himself and get whoever was around to pitch in depending on their abilities. I was probably Crusty Bunker #2. I did more of it than anyone other than Neal. He trusted me to do main figures, etc. Other guys might just do backgrounds or whatever depending on how good they were. I think it started with a couple of Dr. Strange books penciled by Brunner. We were all pretty much friends anyway and would help each other out however we could if someone got jammed up.

JAMES: Those Dr. Strange issues were gorgeous!--if a little visually chaotic because of the mix of ink styles. I remember some Crusty Bunker ink jobs on Fritz Lieber “Fafhrd & the Grey Mouser” adaptions that Howard Chaykin penciled in DC’s Sword of Sorcery. Would these jobs always be done on-site, or did people take individual pages home to work on?

RALPH: The work was always done on site at the 48th St. office. I moved out to New Jersey in the mid-70s and so stopped renting space there. I would stop by and visit when I was in town like a lot of other people but mostly worked out of home after that.

JAMES: How did they split the page rates? And, was everyone paid in a timely fashion at Continuity?

RALPH: Neal would go over the pages before turning the jobs in and split up the money according to who did what. I never had any complaints…he was fair.

JAMES:You’ve worked a lot with Larry Hama--- multiple pieces at National Lampoon, and the split porn story with him and Neal Adams for Flo Steinberg’s underground one-shot Big Apple Comics-- and then later a story in his Savage Tales b&w magazine for Marvel.

RALPH: Larry Hama is one of my oldest friends. We know each other from the High School of Art and Design and it was through his influence and that of JD Smith that I first started considering comic art as a realistic career goal. After Larry got out of the Army we became pretty much partners for several years. I always respected his talent, inventiveness and storytelling ability. He helped me with penciling on a lot of stuff through the early and mid 70s.

I had a bit of a head start on him career wise because I had been working for Wood while he was still in high school etc. Larry also served an apprenticeship with Wood a little later on when WW was doing the Overseas Weekly strips and living in Brooklyn... so we had a lot in common in terms of how we would approach the work. Then when Larry started doing Wulf and Iron Fist and doing more writing, he kind of moved on and went his own way.

JAMES: About the series of “One Year Affair” and “Two Year Affair” strips you did for National Lampoon’s Funny Pages section with the late editor, writer and early book market graphic novel packager Byron Preiss: I like “OYA” a lot and it is sort of dryly funny. I loved the Funny Pages with you and Jeff Jones and Vaughn Bodé. No doubt the comics were some of the best stuff in the Lampoon. Adams did some of his strongest work ever there, using the full color slick magazine printing to advantage.

RALPH: Personally I always read Charles Rodrigues’ strips first. Now THAT was funny....

JAMES: I liked “Trots and Bonnie” by Shary Flenniken, too.

RALPH: Absolutely. She and Bobby London rented space up at Continuity for a little while, but I never got to know her very well. (National Lampoon art director) Michael Gross told me many times that the only reason they were running the “OYA” strips was for the art. Byron didn't really have much talent as a humorist. Fortunately for me they gave Gross pretty much free reign to do what he wanted with the Funny Pages. “Idyl” wasn't really funny either, but he just let Jeff Jones do his thing.

JAMES: “One Year Affair” is funny though and it stands among the most true reflections in comics of the sensibilities of the 1970s, for those of us who lived through them. Did you participate in the plotting or have input in how the narrative situations played out?

RALPH: I had not much input into the writing. I pretty much let Byron do his thing. If given my druthers, I might have made the male character a little less nebbishy. I tried hard with the backgrounds, costuming etc. to make it an accurate reflection of the times.

JAMES: Did you base a lot of the characters’ appearances on people you knew? I tend to do that for longer pieces---base characters I will have to draw a lot on someone I know well--it helps keep them “on-model,” as they say in the animation biz. Did you have people model for you or take photos, or just draw from memory, or from your imagination?

RALPH: I posed photographs for a bunch of the strips, but one problem that I had was that I couldn't get the same girl to model for me more than a couple of times in a row. Something of the character of the model would inevitably seep into the drawing of Jill so she was not always as consistent as she should have been. Sometimes things do fall into place, though. (Cartoonist) Jack Abel was perfect as Steve's dad and he was renting a room just down the hall at Continuity.

JAMES: Is that your general practice? I mean, you started with Woody, who kept a large scrap file. Reference is really important when you are drawing realistically---to understand how things work and what they look like from many angles, etc.

RALPH: In the beginning I used "scrap" a great deal and kept extensive files of photo reference and also of other artists' work, as I learned from Wood. I used to spend whole days just cutting out pictures from magazines and filing them. When I was up at Continuity we would all pose for each other whenever needed and you have probably seen some of those photographs. I used photo reference a lot in OYA but as I have mentioned before it was always a problem to get the same girl to model for me more than a few times, especially since I wasn't paying anything. So some of the character of the models would seep into Jill, and her appearance was perhaps a bit inconsistent.

I never based my characters on people I knew other than in the “Rats” story for Marvel where I made myself and my girlfriend the main characters. Once in a while we would draw friends into a panel just for laughs. The only comic job I did where I used models consistently was that unpublished thing I did for the Navy where Paul Kirchner was the main character and a couple other guys from up at Continuity were other soldiers. These days I don't keep files; if there is something I need reference for, I just Google it and print it out.

JAMES: The great sci-fi writer Samuel "Chip" Delaney told me he wasn't thrilled with Empire, the book he did with Howard Chaykin for Byron. And Jon B. Cooke said that other people also had issues with Byron. You and Steranko seem to have worked with him the longest and you both did some strong work with him. And Preiss spoke very highly of both of you in Jon’s unpublished interview with him that he was nice enough to send me. Many of Byron’s projects were directed towards developing mass market comics formats, so that is to his credit. But would you say your experience with him was positive overall?

RALPH: I have mixed feelings about Byron. We did some good work together but also a lot of crap. He acted like he was my friend and later did me a couple solids like referring me to the Choose Your Own Adventure people (at Bantam Books-J) and recommended me for a job at an animation studio, but nobody ever got rich working for him. In the end he treated us all like servants. I guess that is what capitalism is all about. He came from money; his father was a big shot corporate attorney with a whole floor at 666 Fifth Avenue. So there was a class difference there that made itself felt.

JAMES: Son of Sherlock Holmes is little problematic, NOT because of your as always scrupulously detailed efforts, but because of Byron's convoluted story and all the heavy typesetting etc. The edition I have is the larger trade paperback “deluxe edition,” but I bet it looks a lot better in the regular, cheaper digest-sized newsprint version---as Steranko's Chandler definitely does. This stuff is pulp, it seems intended to be seen in the smaller format and newsprint absorbs the color better than the paper stock of the deluxe version.

RALPH: As I have stated elsewhere, doing that Son of Sherlock book was one of the biggest mistakes in my professional life. It went on forever and it was SOOOO boring... and it went straight to the remainder racks. I let Byron talk me into it by saying anything with Sherlock Holmes’ name on it would sell. He was wrong. And it didn't pay shit. I did some nice art on the first thirty pages or so but eventually I lost faith or interest in it as I could see where it was headed.

JAMES: Well, the Fiction Illustrated books were way far ahead of their time. I don't think a lot of people were looking for comics in bookstores then. And apart from his innovative publishing and editing ideas, Byron is less coherent as a writer--he was very lucky to have people like you around to try to make sense of it. Some of your sequences are really nice. But it is always a mistake to put multiple inkers on a project--it makes for a dis-unified finish.

RALPH: Supposedly the idea was to have Alfredo Alcala ink the period stuff in the intro to give it a different look, but he did a sloppy job... probably because the pay was lousy.

JAMES: Oh, there is no doubt that Alcala was talented—his work often resembled that of the great book engravers. The Filipino and Spanish artists that Warren, DC and others began using so much to sidestep American comic artist’ efforts to unionize put huge amounts of effort into everything they did, because their low US page rates translated well into their currency. But Alcala’s heavy inks could also overpower artists like John Buscema (on Conan), Kirby (on Destroyer Duck) and in Byron's books, Tom Sutton (in The Illustrated Harlan Ellison) and you. I was taken aback at how weak what he did on you was, right in the front of the book.

RALPH: Wasn't my idea and yes, I was disappointed.

JAMES: Steranko has wanted to get his Chandler back into print for years. He redid the art for a chapter, fully rendered digitally so the panels look like airbrush paintings, that ran in Dark Horse Presents, but that's it. Could the Sherlock book be reprinted?

RALPH: Efforts to reprint any of the BPVP inventory have been stymied by the fact that Preiss' estate sold all of the rights to the material to a person or business entity that has no interest in the material. They don't even respond.

JAMES: Are there plans to reprint the whole series of “One Year Affair” and the never-completed “Two Year Affair”?

RALPH: Charles Pelto of Classic Comics Press who did nice reprint books of many classic newspaper strips wanted to do a OYA/TYA book but finally gave up after beating his head against the wall for a while.

JAMES: I would guess that all the Funny Pages material was artist-owned. Bode's Cheech Wizard is kept in print and the proceeds go to his heirs. I have them, and I have a nice book that was done recently of Jeff Jones' complete Idyl. Fantagraphics recently ran a bunch of “Trots and Bonnie” pages in Sammy Harkham’s Kramers Ergot. Given that Byron is long dead now, isn't there a sort of reversion that should happen for a living collaborator?

RALPH: Byron and I held the joint copyright to the “One Year Affair” and “Two Year Affair” material. Neither one of us could do anything with it without the other. When he died his widow sold off the rights to all his stuff to some NY agent. Mr. Pelto and others have tried to contact him regarding rights to the material but he doesn't even answer. But if we were to go ahead and publish something without his permission we could be sued. So we are kind of stuck in limbo.

JAMES: I think that might be challengeable legally---you'd have to consider the expense against the potential profit of a collection. It is a significant work.

To switch gears, I consider color to be one of the most important aspects of comics, maybe the first impact of the reader, but that part of the process was for so long underpaid and underappreciated, and still often is. You obviously DO color and very well---I see that you colored the Sherlock book for Byron very nicely and you do brilliant coloring on your commissions.

RALPH: I always considered the coloring to be part of the art and made every effort to always do it myself. Same thing with lettering for that matter. Back when I was first starting out I picked up a few jobs coloring or lettering other people's stuff when things were slow.

JAMES: Did you do any color guides for Wood (did he train you about that at all?), and/or for your stuff at Marvel or DC?

RALPH: I did some coloring for Wood on the Thunder Agents but mostly he had Tatjana color for him and she certainly had the skills.

JAMES: What advice did Woody give you about coloring?

RALPH: I don't know if he ever gave me any ... I know he thought it was an important part of the art and could ruin an otherwise good job if done badly. Maybe he did suggest trying to work out an overall color scheme, working opposite ends of the color spectrum for contrast... red against green, yellow against purple, blue against orange...and to fade colors as they recede into the background.

You want to use color to draw the eye to where the action is happening. Overly bright color all over can just make it a hodgepodge. That was one thing I hated about what Valiant did with a lot of my stuff...then you run into these idiot marketing guys who tell you stuff like "red sells".... no, dummy, good art sells.

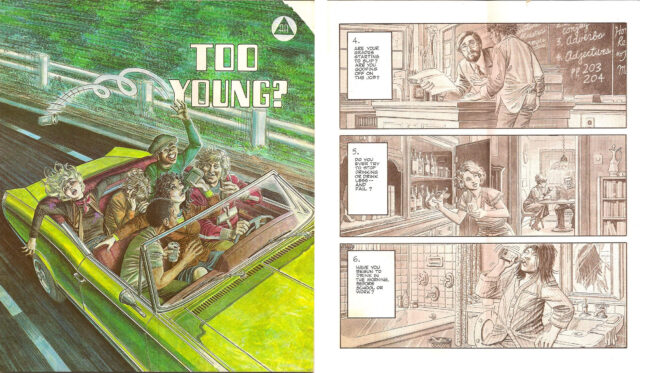

JAMES: I saw the alcoholism comic you did on Facebook. I love these kinds of meaningful uses of comics, and this is a great example of it done well. I was trying to date it—I saw one selling as “rare” on Ebay for $25, that was dated 1979, but another guy commented on your Facebook post that he had seen one at an AA meeting in 1988, so it was kept in circulation for quite a while. What this done for?

RALPH: Too Young? was a booklet sponsored by Alcoholics Anonymous and distributed for free at their meeting places. It would be indiscrete to publicly name the person who was on their executive committee and was my contact there.

I don’t know who wrote it. I think 79 is probably closer to the truth because Larry Hama helped pencil some of it and we were still working together up at Continuity.

JAMES: Who among the editors that you worked with at DC, Marvel and other publishers that were particularly sympathetic and/or effective?

RALPH: Ron Barrett was my editor at the Children's Television Workshop magazines and also for a while at Lampoon. He is a very clever and funny guy and I always enjoyed working with him. There was nobody special at DC or Marvel for me. I worked with Joe Orlando, Dick Giordano, Roy Thomas, maybe a couple others at Marvel that I don't remember. They all treated me okay but I didn't have any special rapport with any of them…though of course I always got on well with Larry Hama, we were friends from high school. I did a few things for Crazy when he was there. I always had the greatest respect for Archie Goodwin although I only did one thing for him and I think he was disappointed with it. I did a five or six pager for Epic when he was editing. It was a humorous b&w thing about husband and wife space explorers. But it wasn't a great art job and maybe wasn't even that funny.

JAMES: I remember that—it is better than you think. I was in a few issues of Epic too.

RALPH: I liked Terry Bisson up at Web of Horror; we became good friends.

JAMES: But Bisson ran off with all the unpublished Web of Horror art and left you guys screwed, no?

RALPH: No. Terry didn't have the art. The publishers, the Sproul family did.

JAMES: Oops, okay. I see that all the stolen work from that issue by Bernie Wrightson and you et al went up eventually for auction at Heritage. But the original comic art market apparently has no system of provenance, as exists in the fine art world. Is there any legal recourse when you see work like your gorgeous unpublished story from Web being sold at auction?

RALPH: Heritage did in fact pay me for the stolen Web artwork that was sold on their site, although I had to split the money with whoever it was that came into possession of it.

JAMES: Back in the day, DC gave art away or ripped the boards in half and tossed them in the garbage for many years, until, it is said, Neal Adams raised a stink. At Marvel, apart from many instances of art given away to fans and other people passing through the offices for various reasons, some staff members took what they wanted from the warehouse and offices and sold a lot of it at early comic cons in NYC. In 2010 on the TV reality show Hollywood Treasure, a then-current assistant to the late Stan Lee let slip in unguarded moment that Lee had personal storage units “full of art” by Kirby and other artists. I’d like to believe that this robbery was done mostly by editors and writers, that artists would not help themselves to others’ work. Well, Steranko went into Marvel and just took his own art back—he knew his rights, as Adams did. But most artists didn’t know their rights, or have room to store it, or think there was a market for it---and anyway, wouldn't make a fuss for fear of losing work. When Marvel and DC finally made art returns standard policy, they did not do this voluntarily, rather they were informed by their lawyers that they had only bought the publication rights, not the physical objects, the art boards. Did you get original art from DC, Marvel etc. back?

RALPH: Pretty much any artwork from before the late sixties or early seventies had to have been stolen originally since neither the comic book companies or the newspaper syndicates were returning it. There are a few artists I could name who are kind of famous for stealing original art from the companies' storerooms, both their own and other people's. I myself have almost nothing now having sold off almost all of it for cheap money when times were desperate. Gil Kane and Dick Giordano are also reputed to have made off with a lot of original art. Al Williamson managed to sneak a good deal of Alex Raymond art out of King Features. In those days current art did not have a lot of value; you could buy Jack Kirby pages for twenty bucks. I was very active with the Academy of Comic Book Arts to fight for such things as return of art and royalties on sales.

JAMES: Geez, I really can’t assume anything, even about our fellow artists, can I? You eventually became head of that organization of comics professionals, the ACBA, and I think you were a good choice. It is very hard to bring freelancers together into a situation where they might risk their short-term employment--- because face it, we almost always work short-term. So we aren’t coming from a position of strength. But the time was right--- you and the best of your contemporaries like Berni(e) Wrightson, Barry (Windsor) Smith et al had just gone through steep learning curves. You pretty quickly became a sort of quintessential freelancer. At that time as I was growing up, I recall your work being very mature and state-of-the-art. And, you are certainly a solidly left, union-type figure to have in that position.

RALPH: I was pretty active with the ACBA from the time it started and served on its board. Larry Hama served beside me on the board, which also included Marie Severin, Don Perlin, Gerry Conway and Neal himself. There may be one or two others I forgot. My tenure as President must have been 1975 and 76. After Stan Lee and then Neal Adams stepped down as president I wound up with the position. I didn't even especially want to be President, but I didn't want Gerry Conway to take that post.... he was trying to push the idea that writers deserved part of the original art out of sheer greed.

JAMES: That figures---he was one of the most awful of the young fan writers who came into comics in the 70s; he later ended up finding success in television writing shows like Law and Order. Guys like that would love the credits now, where writers get top billing on graphic novels while the artist’s names are tiny or left off [of] covers entirely.

RALPH: My feelings about it were that writers were welcome to their original script back and nothing more. Of course I backed the idea that they as well as artists should get royalties on reprints, spinoffs, toy deals, etc. I didn't necessarily feel I really had enough clout to be That Guy but I didn't want Conway to take over and apparently most of our members agreed. Trying to organize comic artists and writers was like the proverbial herding of cats. It wasn't long after that that it kind of fell apart. I don't think I was a strong enough presence in the industry to hold it together. It really needed someone like Neal or Jack Kirby to be the figurehead. That being said, I like to think that we helped to get some justice for guys like Siegel and Schuster and later Kirby, and to eventually get standards changed so that original art was returned and royalties paid... not to mention things like health insurance, etc. Our main function was just to raise awareness of these kinds of issues among the creator community and to encourage our members to fight for and demand these changes. We had no real power but we did have some influence. Creators today have benefitted from our educational efforts.

_________________________________

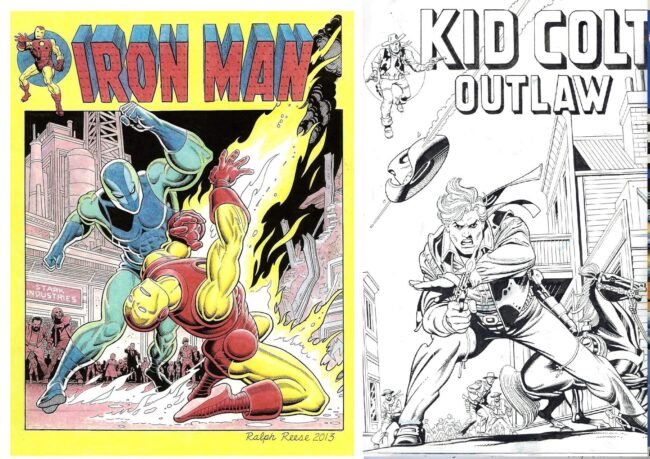

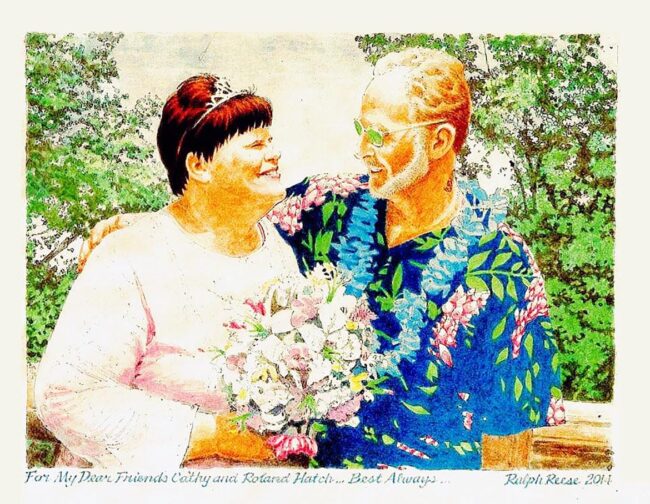

More recently, Ralph Reese has been doing commissions for fans----gorgeous portraits, and meticulous recreations of comic book covers or pages. He can be contacted by private messaging via Facebook. There is generally a several month long waiting list, but his prices are very reasonable---too reasonable, in my opinion. “I’ll negotiate with people depending on what it is they want,” he says.

Some of his most amazing recent efforts have been perfectly rendered, brilliantly colored recreations of classic sci-fi E.C. covers by Wally Wood.

A few of Ralph’s vibrant portrait commissions:

_______________________________