If Derf Backderf’s book Kent State: Four Dead in Ohio were presented on television, it would be called a documentary. We don’t yet have an equivalent term within the realm of the graphic novel, “novel” implying fiction rather than fact. And this volume is crammed with fact, so when, in the 28 pages of notes at the end, Derf substantiates his opening assertion that the book “is based on eyewitness accounts, detailed research, and extensive investigation,” we believe him.

Derf has recreated herein many of the events that led at Kent State University on May 4, 1970 to the National Guard shooting at unarmed college students who were protesting the Vietnam War (and the presence of the National Guard on campus).

“In a deadly barrage of sixty-seven shots, four students were killed and nine wounded. ... Using the journalism skills he employed on My Friend Dahmer and Trashed, Backderf explores the lives of these four young people and the events of those four days in May, when the country seemed on the brink of tearing itself apart.” —Book jacket front flap.

“My God! They’re killing us!”—Freshman Ron Steele

The storytelling is achieved by combining a series of isolated instances, each developed on its own, as a story with a beginning, middle and end. There may be other ways to tell the story of the Kent State shooting, but this is the best way. By telling his story this way, Derf avoids the pitfall that many factual graphic novels slip into—captioned pictures, which are inherently without the dramatic impact that engages a reader. Derf’s method has impact.

The book is organized chronologically, beginning with a chapter entitled Thursday, April 30, which focuses on nearby Richfield, Ohio, where the National Guard has been called in to deal with strikers.

In the next chapter, Friday, May 1, the attention shifts to the Kent State campus. There, hippies, anti-war protesters, SDS, and Weathermen are mustering. Daytime is peaceful; at night, the protesters take action, marching and chanting.

Derf introduces various students. While his selection may seem random, he is attending to the students who, three days later, will be killed.

Saturday, May 2 shows us campus life, largely peaceful, at least during the day. Students are now protesting the ROTC operation on campus. That night, they set fire to the old ROTC building (no longer used by ROTC, but symbolic still). The National Guard arrives and starts using tear gas. Helicopters hover, watching for ...?

The chapter on Sunday, May 3 shows us National Guardsmen on duty. We get glimpses of student life, but the emphasis is on student protest against the Guard’s presence and against a curfew that has been imposed. Derf discusses the undercover operation: apparently the FBI, the CIA, highway patrol, city police and Military Intelligence all have operatives in the field at Kent State—from plants to informants to agents provocateur.

During encounters with demonstrators, Guardsmen actually use their bayonets on protesters and even random student passersby.

ON MONDAY, THE FATEFUL MAY 4, the student protest against the presence of the National Guard culminates during a noon rally. The Guardsmen, often pelted with pebbles and refuse and other detritus that students are throwing at them, become angry at the students. Angry and frustrated, a dangerous mix of emotions.

In this hostile situation, Derf introduces us to the person in charge of the National Guard— Brigadier General Robert Canterbury, a belligerent “my way or the highway” kind of guy, exactly the wrong person to be in charge in the circumstances of the campus at Kent State. He mistakes thousands of students moving from class to class or pausing to watch the unfolding drama on the commons as protesters defiantly ignoring his edict to clear the area.

He decides the students constitute an illegal assembly, saying: “It’s time for these students to find out what law and order is all about. Bayonets! Mask up! Lock and load!!”

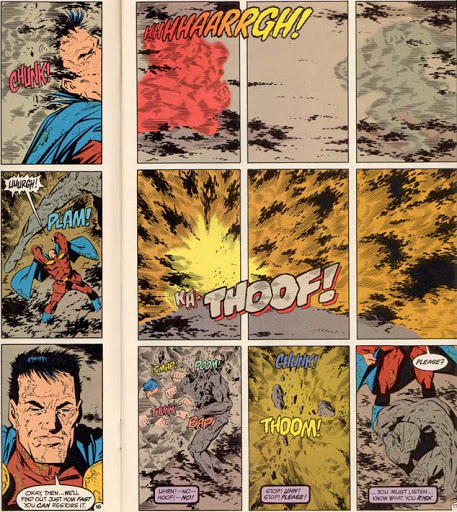

Student protesters continue to pelt the Guardsmen with rocks and other debris, calling them “pigs” and “fascists.” The Guardsmen are smoldering with anger. They’re lined up, facing student clusters at some distance across a parking lot. Then comes an order:

“Guard! All right—prepare to fire! Guard! ...”

G Troop wheels completely around in unison—and opens fire. At the sound of gunfire, other Guards units open fire.

At this point, Derf focuses on the individual students being killed or wounded, grotesquely describing their fatal wounding with clinical— surgical—precision:

“The bullet blasts out the back of his skull and severs his spinal cord and carotid artery.”

“The bullet enters the back of her left armpit and shatters on an arm bone. The shards rip through organs and arteries.”

“He is shot in the groin. The bullet blows out a three-inch hole in his back as it exits.”

“Half his foot is blown off.”

“He is shot in the back of the neck. The bullet narrowly misses his spine and bursts out of his cheek.”

“The bullet tears out the right side of her neck, destroying her larynx and severing her jugular.”

“A bullet slams into his back, tears through a lung and his diaphragm and shatters three vertebrae. He is instantly paralyzed from the waist down.”

“The bullet breaks five ribs, tears through his lung, and exits through his shoulder.”

The extensive damage done by bullets tearing internal organs apart is due to the type of ammunition issued to the Guardsman that day—armor-piercing bullets, designed to pierce the light body armor as well as the sturdier stuff of tanks and other assault vehicles. Soft human tissue offers no resistance so bullets intended to break their way through steel burrow and rip their way through flesh.

On the commons, an enraged crowd of students behave as if they’re out for blood. A passionate professor gets a megaphone and begs them to disperse:

“If you don’t disperse right now,” he says, “—they’re going to move in and it can only be a slaughter! Jesus Christ, I don’t want to be a part of this!!”

Miraculously, the respected prof’s plea works. “The curses stop. One by one, the students turn—and leave.”

The crisis is over.

The university closes and tells students to leave. Go home.

AT VARIOUS PLACES in the narrative, Derf breaks off into straight typographic text to give the history of Kent State, for instance, or to describe the organization of the National Guard on campus that weekend or to discuss the records of various politicians, the governor, the mayor, or to outline the growth of the student protest movement and SDS or other historical aspects of the situation.

Derf is good at conjuring up the politics of the time—the anti-war feelings, Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin. The student protest seems based largely upon avoiding the draft not so much on opposing the war. (I said that over twenty years ago in a book of mine.)

During the action on May 4, Derf supplies several diagrams, showing in precise detail the movement of the National Guard and the location of student protest groups, which clarifies the situation as it unfolds.

Derf’s drawing is easy to criticize. The wrinkles on clothing are too dark and too numerous, belly buttons are solid black dots, the distance between the belt-line and the crotch is too short, and he persists in drawing the philtrum (that depression between nose and upper lip) on every face in every perspective.

But the book is undeniably a great work of imagination. All the facts are available from various sources (Derf lists all of them in the notes; he read them all), but to turn the facts into a narrative in which people are acting and reacting requires great creativity. And this book amply reflects that. Nearby, I’ve posted scans of a couple pages that demonstrate Derf’s imaginative creation.