There was this question of how I come up with the “off-the-beaten path” subjects I write about. The editor wondered if I would read a “major figure.” He wondered, for example, what I would make of John Porcellino. He thought my treatment of my major illness[1] would interest me in Porcellino’s treatment of his, like we had pulled matching decoder rings out of the cosmic Cracker Jack box, enabling special understanding of one another.

There was this question of how I come up with the “off-the-beaten path” subjects I write about. The editor wondered if I would read a “major figure.” He wondered, for example, what I would make of John Porcellino. He thought my treatment of my major illness[1] would interest me in Porcellino’s treatment of his, like we had pulled matching decoder rings out of the cosmic Cracker Jack box, enabling special understanding of one another.

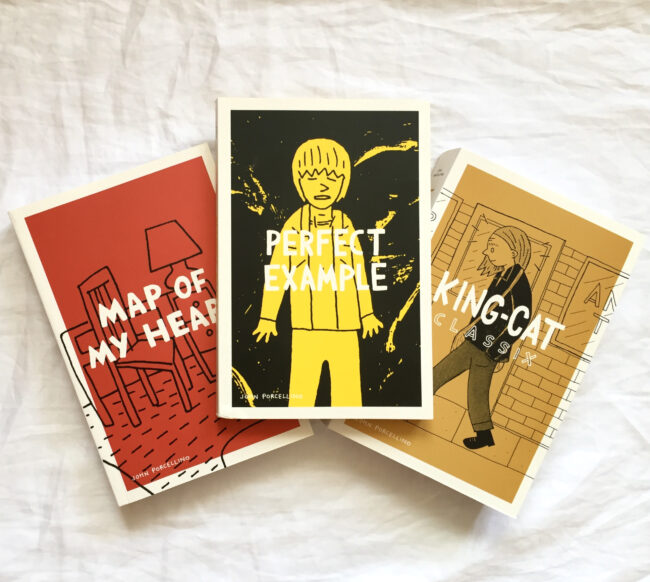

Drawn and Quarterly sent me King-Cat Classix and Map of My Heart, its 2020 two-volume reprinting of Porcellino’s Best of King-Cat Comics and Stories (1989 - 2002), accompanied by his Perfect Example (D&Q. 2020). Since I had never read Porcellino and Perfect Example was 129 pages vs. the 727 of the collected Cats, it seemed a good place to begin.

I.

If I have this right, King-Cat is a self-published, autobiographical mini-comic, from which, in 2000, Highwater Books combined two stories, one from issue 52 (May 1997) and one from issue 53 (Feb. 1998), both set between May 1986, the end of Porcellino’s senior year in high school in Hoffman Estates, a suburb of Chicago, and August 1986, before his departure for college, and published them as Perfect Example. This book was republished by D&Q in 2007, but its most recent edition is the only one I have seen. It contains a near three-page “Resume and Relevant Information” Porcellino seemingly wrote for it. Other than that, I have no idea how it differs, if at all, from the 2007 or 2000 editions, or how they may differ from the original stories in King-Cat.[2]

Anyone who has read other cartoonists’ accounts of high school is unlikely to find Porcellino’s especially surprising. (It may not even surprise anyone who’s been to high school.) The most surprising thing to me was how out-of-the-1950s life in 1986 Hoffman Estates seems to have been. The kids drink but do not do drugs. They make out but do not have sex.[3] The problems of the outside world do not intrude upon them. Everyone is heterosexual. Everyone is as white as the characters in “Peanuts,” B.F.[4] This “sameness” is accented by Porcellino’s drawing. I often found it difficult to distinguish one character from another. I often found it difficult to distinguish boys from girls. At one point Porcellino refers to himself as “fat” but he seemed no chubbier than anyone else. (Little Lulu’s Tubby, he is not.) Dialogue does not often aid differentiation. “Blah,” one character says; “Blah,” another answer. A second conversation consists of “Chit” and “Chatter.” (Actually, I liked both.) Sometimes the background of outdoor night scenes are as blank (“light”) as outdoor day scenes. Even time barely matters. “Later,” “a few days later,” “some weeks later” sit atop panels; one event is over and another has begun.

And these events are not momentous. Porcellino and friends go to class, clubs, concerts, visit thrift stores, Chicago, party by the lake or each other’s homes, skateboard, talk on the phone. Throughout though, Porcellino sets himself apart. He is unable to “fit in,” lacking in direction, “sad,” occasionally suicidal. “(N)othing ever turns out as [he] hope[s].” Everything is “shitty.” Everything seems a “waste.” (“N)othing really matters... (T)hings (are)... no more real than shadows on a wall.” But one mid-summer’s day, while mowing his lawn, he experiences an epiphany. He realizes that he creates his “unhappiness” “(T)hings aren’t in themselves good or bad. It’s the way I react to them...”[5]All he must do is change his reactions. And at book’s end, having immersed himself in nature, having hiked past rocks and logs and over “moist, mossy earth,” sun breaks “through the darkness,” and he is “very happy.”

Porcellino omitted from his portrayal of his pre-college self that he was already creating the comics and zines which would become the focus of his adult life. He also omitted any exploration of his earlier years which might have provided insight into the development of the adolescent he became. Which brings to mind a second surprising thing about Porcellino. I cannot recall an UG/ALT cartoonist who expresses such consistently warm feelings toward his parents. (I can barely think of a friend or relative who does.) Whether he is driving 1000 miles alone in a car with his father or weeding a garden with his mother, only positivity (and cartoon “hearts”) vibrate. (The sole exception – a brief one – occurs when nagged about a haircut.)

I tossed this puzzle to my consultant on all things familial, Ruth Delhi, who snapped upon it like a seal a mackerel. Porcellino’s parents, she surmised, must have been worried enough about their depressed son to support anything he actually wanted to do. He was allowed, seemingly without criticism or complaint, his less-than-glam jobs, his relationships that didn’t gel, and, most significantly, the $.50-to-$2.00 self-published comic that anchored him. And Porcellino, for reasons that he leaves unexplored, who had been unable to separate from his family via a typical adolescent rebellion, was grateful for this support. He knew he needed it, and his appreciation shines through his work from start to finish.

Which is more than nice.

II.

According to information gleaned from the “Resume” and D&Q’s King-Cats, during the 10 years that elapsed between the events that became the basis for Perfect Example and its creation, Porcellino immersed himself in the zine world, began his signature comic, graduated college, toured in a band, worked in a warehouse, at a mortgage company, and as a mosquito abatement man, moved to Denver, had several girl friends, opened a publishing house/record label. He also, at various times, felt he still lived “in shit,” amidst an “unforgiving” society, was “pretty miserable,” endured six-years of a “broken heart,” was “out of [his] mind” from “anxiety” and “depression.” (He also, experienced “mystical visions” that restored his “faith in God and Meaning.”) In January 1995, he came down with hyperacusis, an acute sensitivity to noise where even a click from a light switch could cause him extreme pain. He withdrew into a private world of girl friend, cat, comics, and records.[6] He took up yoga and meditation. (It helped him regain a sense of order and restored his self-confidence.) In late September 1996, he married Kera, an “old sweetheart” he had known from Illinois.[7]

I note all this to emphasize the choices that went into the creation of Perfect Example. Given all that Porcellino experienced between the summer of 1986 and his writing about it, it was not inevitable that he would end his tale with “sunlight breaking through... darkness.” If he had written his book at a different point in this decade, the heavens might have unleashed tornadoes, hurricanes or locusts. The uplifting ending was a gift from a Porcellino who differed significantly from the Porcellino who had lived the events depicted in his book, or who had lived through the years before he sat down to portray them. Whether and in what proportion marriage, meditation and illness contributed to this shape-shift is a question for the gods.[8]

A former Porcellino could also not have drawn Perfect Example either. In an early King-Cat, he defended himself against criticism of his “crappy line, scratched on paper” thus: “Why bother spending 3 hours on a drawing if the world could end tomorrow?... If the world is a piece of shit, art that denies that is a lie. It is more important to me to make art that is an honest expression of my life than it is to make pictures people think are well drawn.” But by the time he came to picture his story, he had softened.

His art may be, as I have said, reductive. But by de-emphasizing distinction, it stresses commonality. By avoiding edginess, it invites closeness. It may be “bland” – or, as ice-cream flavors go, “Vanilla” – but there is comfort in its simplicity. Its casualness soothes. Unlike Porcellino’s earlier work, heads do not slant across pages in painful diagonals. Deboned limbs do not droop, wet noodle-like. Panels are orderly in size and spacing. Borders do not wobble. Neither violence nor freakish goings-on occur within them. Aside from the opening story, solid (evil) black does not extinguish ample (good) white.

It sets a tone of peacefulness achieved. Swords into ploughshares. Lions and lambs.

In its blankness, it is easier to see ourselves.

III.

When I am writing, much that occurs around me assumes significance in relation to this work. So I was not surprised that I took special note, while reading Adam Martz’s review of Emile Zola’s 20-volume, multi-generational novel, Les Rouges-Macquart, in a recent NYRB, that it “teems with livid characters who kill, seduce, drink, ravish, thieve, betray, and mutiny.” Well, I thought, that is one way to go about it. Another approach, in the very same issue, was expressed by Leo Rubinfien, analyzing Japanese photobooks. “(P)ictures are fractional to begin with and... interweaving them... can unlock and augment their meanings.... Our disparate world may be hung along a thread of ‘feeling’ and interweaving can underscore their relevance to one another.” Which seems more like Porcellino’s.

In the 13 years of King-Cat placed before me, there is drink (mostly beer) but not much in the way of murder, seduction, rape, theft, betrayal, or mutiny. However, if you consider each panel – even each individual issue – as a “fractional” part of a Rubinfien-esq whole, hanging, interwoven, in your mind along the “thread of feeling” they establish, they may deliver a no-less effective story without all that Zola-nistic SLAM! BAM! The story of one life being lived by one person may provide ample drama.

Soon after completing King-Cat 52 (May 1997), which contained, you will recall, the first portion of PE, Porcellino revealed, in KC 53 (Feb. 1998), which contained the second portion, that he had undergone surgery to remove a life-threatening tumor. Being that close to death, he wrote, had been his “most intense and powerful experience.” It brought him “clarity.” He experienced profound gratitude and felt his “most alive” ever.

Did his survival account for that sun breaking through clouds? Was that ending already on paper or in mind before the entry of the surgeon’s knife? We do not know, but I, as the editor surmised, who came through the imposition of a centering scar down the middle of my own chest, nod in recognition of the lesson and luck.

"I do not recommend it,” I frequently say. “But you can get a lot from it.”

IV.

The immediate situational change recorded by Porcellino is that, by issue #54 (Sept. 1998), he and Kera have returned to Illinois. The Midwest, he felt, with family, friends, familiar roads and fields, is where he belonged. He is now 30-years-old, a “stockboy” in a health food store, and thinking, “One day it’s hazy and grey – one day it’s clear and bright but...,” quoting a Zen priest, “‘they’re all one day.’” And then, one moment in the course of this infinite day, Kera leaves him, and he is transformed into “a hermit... with a small black cat.”[9]

This image slips into issue 55 (May 1999). Porcellino confides only that much has happened to him but, about which, he doesn’t “know what to say.” Four months later, Kera and he divorce, but neither separation nor divorce is revealed until issue 57 (Aug. 2000). He also does not reveal, until his “Notes” in the back of Map Of My Heart, that, not long after their return to Illinois, he again became extremely ill, possibly from past exposure to toxic chemicals, and that, as he recovered physically, his psychological state – anxiety, depression, OCD – worsened.

From these “Notes” and “Selected Journal & Notebook Entries,” also appended to MOMH, we learn Porcellino began therapy, went on meds, plunged deeper into his Zen practice. His anxiety lessened, but his depression and OCD became worse. He could barely work. His mind seemed to have broken apart. He had difficulty with balance – with speaking. The world seemed unreal, “pointless,” “on the brink of chaos and horror.” He wanted to die. But, he told himself, Go on; do not think; let things be. He felt sorrow in leaves, awe at storm clouds, came alive in rain, saw God in a streetlamp.

These revelations deepen what occurs upon the pages of the later (57 - 60) issues of King-Cat. Without this information, their content, while fine, seems – I don’t know – “delicate.” It waves at what Porcellino is living through but fails – elects not – to grapple with it. Perhaps it is a matter of artistic choice, an election for an approach akin to sumi-e, Japanese brush painting, rather than the impasto of more confessional Western portraiture; but Porcellino had once described King-Cat as being “a totally personal statement from me to the world,” and I wonder if this is not a falling short.

On the other hand, a “statement” can be “totally personal” without being total. (As if any work could ever be that.)

And this additional information, if after the fact, is brave and rewarding.

In any event, Porcellino’s toxic poisoning, psychotherapy, medication, physical and emotional problems go essentially unmentioned in these issues. (There is a single story, entitled “Mental Illness,” eight blank panels, some words in each, in which a void speaks for itself.) His Zen is more of a presence.[10] He takes long, solitary walks, mindful of snow flakes and sidewalk cracks. He listens closely to “wind,” “rain” and “tears.” But what is most constant of his layered travails is Kera’s absence and, here again, “delicacy” prevails.

In an untitled story set in a supermarket, he is “thinking of you (unnamed),” “going nowhere, doing nothing.” In “Last Night the River Froze,” he is in a cold wind, where, “Sleepless... I called out your (unmentioned) name.” He concludes “Forgiveness,” an otherwise, unrelated story, by wailing over-and-over, “I’m sorry!” Most powerfully, in “Introduction to the Night Sky,” after revealing to a friend that “she” (unnamed still) is planning to leave him, he speaks of a time early in their relationship when, having lost sight of her in a Target, he thinks “What if she was really gone? What if she just disappeared...? What would I do?... What if it had just been a dream?”

For me whose most frightening recurrent actual dream is one in which my wife has left me, and who is relieved to the point of shivers each time I awake and find her asleep beside me, these passes at this loss in actual life are gut-tearing.

Maybe that is enough.

V

By issue #61 (Sept. 2002), the final one collected in these three volumes– and the passage of – a symbolically- impossible-to-overlook – nine-months – things have shifted again. Or, as Porcellino writes on the inside of its front cover, “A lot has happened...” He and a woman to whom he has become engaged (Misun) will be moving back to Denver.

The issue itself is short – so short that Porcellino felt it necessary to pad it with sketches. These are of his cat (not Misun), but the final one-pager concludes with he and an (unnamed) she exchanging “I love you”s.

Another sun may be breaking through clouds.

Or, as my wife once said, early in our relationship, “In life, endings are happy or sad, depending on where you arbitrarily decide to declare one.”[11]