CW: This post contains explicit, drawn pornographic images, including an image from a book that was seized in Norway and Oklahoma on obscenity charges.

This interview ran in The Comics Journal #280 (January 2007).

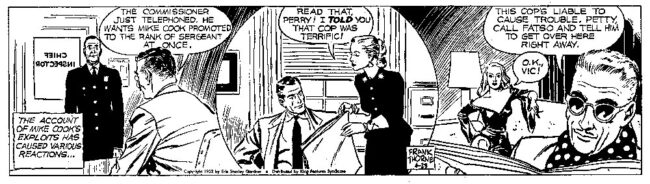

Frank Thorne began his comic-book career in 1949. Like most of his contemporaries of the time, he started off by drawing standard features for a variety of comics publishers, scrounging for jobs, honing his craft in the meantime. His first feature was Ibis the Invincible for Fawcett, he moved to Western (Dell) in 1953 and drew the adventures of Flash Gordon, the Green Hornet, Jungle Jim, as well as adaptations of movies such as 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. He drew the Perry Mason newspaper strip for a couple of years beginning in 1952. In 1957, he drew another newspaper strip, Dr. Guy Bennett. He also worked as an illustrator doing commercial work for corporate clients (such as Bell Telephone).

His work took a turn for the better (in my view) when he moved to DC Comics in 1968, where he drew a variety of second-banana books (second banana because none of them were superheroes, a genre he neither liked nor excelled at) — war, Western, mystery comics. As a kid, I fondly remember reading Tomahawk, a Western comic about a white pseudo-Indian named Tomahawk. I didn’t know it was drawn by someone named Frank Thorne (and I couldn’t tell you to this day who wrote it without looking it up) but I do remember that it had a rough-hewn drawing style well suited to a Western that was unlike anything else DC published (except the war books, which is probably why he was given Enemy Ace to draw later).

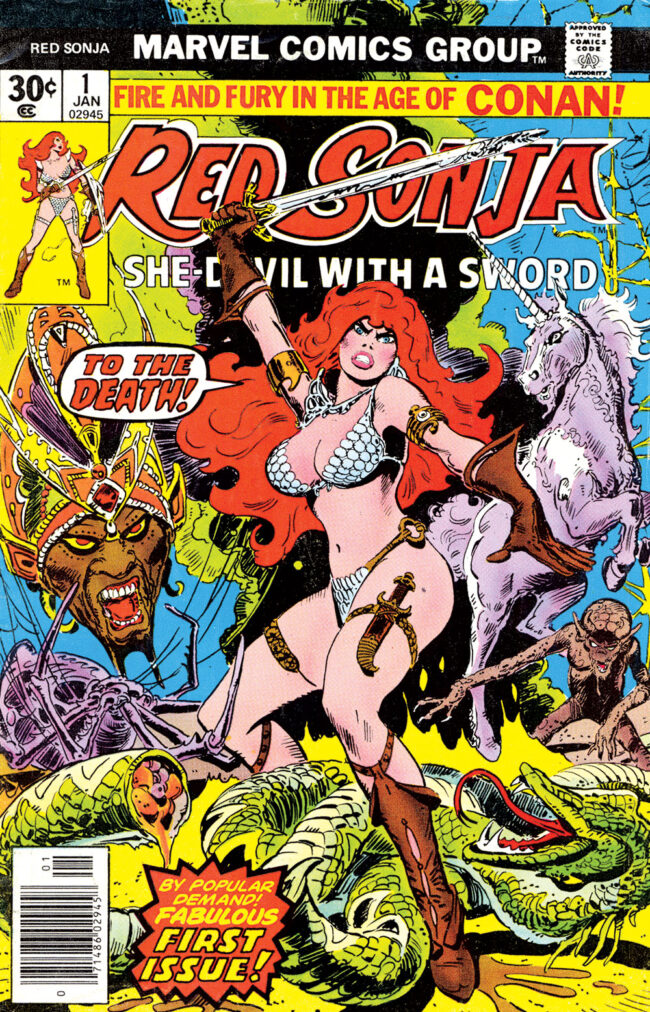

Thorne started moving around in the ’70s: He did a couple of books for Archie’s short-lived action-adventure line Red Circle, then worked on the black-and-white magazines of the similarly short-lived Seaboard/Atlas line where his drawing took on greater assurance and his storytelling and panel composition became freer. In 1975, he started drawing Marvel’s barbarian character Red Sonja, and his life changed forever.

There was no indication in Thorne’s career prior to this that he was any more adept at or interested in drawing women than he was at drawing anything else; his professional output could, up to this point, have been described as competent journeyman work; he drew strips in a variety of genres with equal facility. The 18 issues of Red Sonja he drew changed his professional life and launched him on an unprecedented career arc at the age of 45.

The general perception of mainstream comic-book artists of Thorne’s generation is of steady, commercial workhorses who were more or less content to slave away in the four-color-comics format, and while this is true for the most part, it is astonishing how many of these “workhorses” tried to forge a path of independence from their corporate masters by engaging in risky, entrepreneurial efforts or at least to do work outside their editorial parameters on the side. There were, for example, Ross Andru and Mike Esposito, who published Get Lost, and Joe Simon and Jack Kirby, who started Mainline Comics, both in the ’50s. Wally Wood started Witzend in the ’60s and published several projects of his own (such as The Wizard King). Steve Ditko started doing his Mr. A strips in the ’60s for a variety of independent publishers. Gil Kane published His Name Is…Savage and Blackmark in the late ’60s and early ’70s. Joe Kubert published Sojourn, an anthology of short strips by his contemporaries that lasted two issues, in 1977. In the early ’80s, Neal Adams started the comics publishing company Continuity Comics. And so on. Most of these efforts were aesthetically modest but less mediocre than the generally moronic editorial strictures the same artists had to adhere to under their usual company yokes. Among all of the mainstream comic artists who tried to liberate themselves from mainstream comics companies, Frank Thorne’s attempt was probably the most unusual, as well as the most successful.

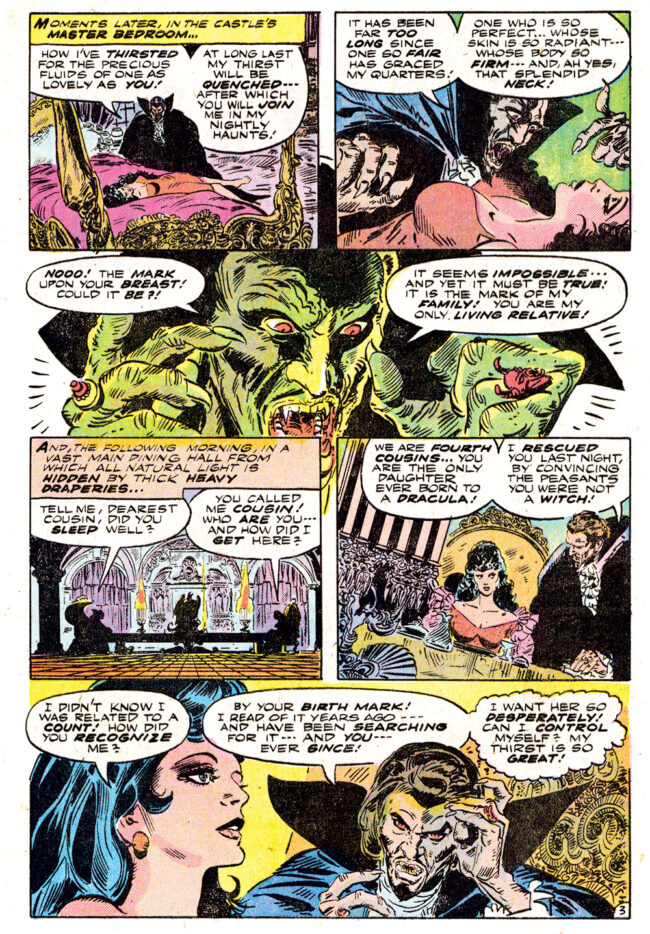

Red Sonja inspired him to wed his art to what was, professionally speaking, a hidden obsession — women and sex. During his Red Sonja stint, he grew his hair long, added a beard, and became one of his own fantasy characters —The Wizard— and traveled the country doing performance art with women who would play Red Sonja (most famously, Elfquest creator Wendy Pini). When this ran its course, he created a succession of women characters, usually in fantasy and SF trappings, who became increasingly sexual and sexualized — Ghita of Alizarr, which originally ran in the Warren 1984/1994 magazine, Lann, which originally ran in Heavy Metal, Danger Rangerette, which originally ran in National Lampoon and High Times, Moonshine McJugs, which originally ran in Playboy, and culminating in his two hard-core comic-book series The Iron Devil and The Devil’s Angel. Last year, he published his first prose novel — Nymph. He is currently writing and drawing gag cartoons for —surprise— Playboy. He found his métier and he went for it, full bore.

I can’t remember the first time I met him, but in 1991, Fantagraphics started its money-making porn division, Eros Comix, and the first person I thought of to contact was, of course, Frank Thorne. We created a series entitled The Erotic Worlds of Frank Thorne, an anthology title that reprinted selections of his previous erotic work as well as some new material he drew for the series. In ’94 and ’95 we published The Iron Devil and The Devil’s Angel, two series that pushed the explicit nature of Frank’s work as far as it could go — or at least I hope so. Frank’s career clearly breaks into two parts — Before Porn and After Porn, with the latter being the work that he’s proudest of and most passionate about. Artistically, he is one of the most libertine members of his generation of artists, and refreshingly unapologetic about it.

The interview reflects the easy familiarity of our professional working relationship, covers every aspect of his career —BP and AP— and reflects the easygoing, libidinal, impish nature of the man I’ve known for almost two decades. It was conducted in five sessions between May and October 2006 and copy-edited by Frank Thorne and Michael Dean.

— Gary Groth

GARY GROTH: You were born on June 16, 1930, in Rahway, New Jersey. Where exactly is Rahway?

FRANK THORNE: My hometown is in Union County in central Jersey. It’s about 12 miles from Newark.

GROTH: Tell me a little about your upbringing. You grew up during the Depression, but based on your memoirs it didn’t sound like you suffered terrific hardship.

THORNE: Depression? That’s what you get after watching the 10 o’clock news! Actually, we fared quite well after the stock-market crash in ’29. My father was a competent draftsman until he reached his mid-40s when he developed a nervous condition and couldn’t continue at the board. He found some menial work and then took a job as the elevator operator for Merck and Company, which was, and still is, in Rahway. My early life was as a farm kid, complete with animals and daily chores. A good neighbor let us farm a field nearby. So I did a lot of going back and forth during growing season, hauling wheelbarrow loads of produce back to the house. We ate a variety of things during the Depression. Actually, we ate starlings. We often had starling potpies. Believe me, squirrel potpies are delicious. Guinea pig and rabbit meat properly prepared make a meal fit for a king! The sunnies that I caught In the Rahway River tasted great fried with butter. Once a week, Mondays, we had chuck steak.

GROTH: A starling is a bird, isn’t it? You shot birds?

THORNE: Oh yes, my father was a hunter. He was always shooting something. Like you, so I’ve heard. You’re an advocate, aren’t you?

GROTH: I only shoot computers and refrigerators, no birds. [Laughter.] Nothing I can eat.

THORNE: [Laughs.] It’s true! I was a barefoot boy with cheek of tan! It was a rural setting. We had livestock: chickens, Muscovy ducks, rabbits and hound dogs running around the back yard. I wrote about that passage in The Crystal Ballroom. It’s a must-read if you want the flavor of the period.

GROTH: When your father was a draftsman, did he work at home or did he work in an office?

THORNE: He worked in the offices of the Steel Equipment Company. That was in nearby Woodbridge. His company was in the shadow of the famous Rahway prison, which made me notorious because whenever you said you were from Rahway, they’d ask, “Do you live anywhere near the prison?” We didn’t, but I always said we did. It’s now the New Jersey Correctional Facility. With that name, it doesn’t have the same panache. It’s stripped me of the only epaulet I had as a youth.

GROTH: So your father was a draftsman — but what did he actually do? What does that mean?

THORNE: He designed office equipment. Actually, he was part of a crew that drafted — he did the drawings — and installed cabinets in the Frick Museum in Manhattan. It was the high point of his career; then the neurological problems ended his drafting days.

GROTH: Did you watch him work?

THORNE: Yes, he had a board in the corner of the dining room and he would bring home some of his assignments. As a kid, I would occasionally watch him work. I suppose it was an early inspiration. My father drew but didn’t have a refined drawing sense. His strong points were the schematics. I still have some of his drafting stuff. You know, a compass, T square and a triangle with his initials “G. T,” carved on them; pop was George Washington Thorne. I’m Benjamin Franklin Thorne. Actually, most of the family calls me “Ben.” “Frank Thorne” is my professional name.

GROTH: So your dad might have inspired you in terms of you wanting to draw.

THORNE: Well, what inspired me most was his huge collection of pornography.

GROTH: Your father’s?

THORNE: Yep. I discovered it early on, and that was really where the drawing-naked-ladies thing originated. [Laughs.] I started to surreptitiously draw from the photos in the old man’s collection. Then I unearthed his modest collection of eight-millimeter stag films. When mom and pop were off visiting, I’d watch them in the cellar, sketchbook in hand — in the other hand. [Laughs.] In this enlightened age, any kid anywhere on the planet can, with a couple of mouse clicks, access the great celestial full-color, high-resolution mother-lode of porn on the Internet. They couldn’t live long enough to see it all! [Laughs.] We’re awash in it, and it has devalued the delicious potency of porn.

GROTH: I don’t want to get too far ahead of myself, but how old would you have been when you discovered this stash?

THORNE: Oh, about 8 or 9. By that time I had begun to yank the crank.

GROTH: You were an early bloomer, I think, relative to my own experience.

THORNE: A late bloomer, eh? [Laughs.]

GROTH: How did being aroused by these images segue into wanting to draw?

THORNE: I began drawing intensely explicit images inspired by my father’s collection. Picasso probably had a father like mine, because he drew some great porn. [Laughter.] In his case, it’s called “erotica.” They showed some of it when they mounted the Picasso exhibit in the Museum of Modern Art years ago. The last display in the show was a very small gallery featuring a discreet display of his naughty drawings and etchings. Man, it turned me on! It was great stuff.

GROTH: We wouldn’t let that happen in an exhibit of yours.

THORNE: [Laughs.] Actually, some of my non-erotic stuff was shown in a gallery at Kean University here in Union, New Jersey. I spoke before a large gathering and got 500 bucks for it! Yes, Gary, like the ad that ran for years in the old comic books said: You can “Make Big Money in Comics!” [Laughs.]

GROTH: I meant we wouldn’t relegate your sexual stuff to a little room. It would be the main exhibit.

THORNE: I produced a lot of it, but it wasn’t all erotica. I loved to draw just about anything. I made cartoons of my classmates, especially the females. I would do sketches on the spot. This eased me through the adolescent passage. I was inept at sports, but I could draw. While the other guys were making cartoons of Nazi dive bombers and Japs getting fried with flamethrowers, I’d be doing naked Nazi ladies with swastika armbands! [Laughs.]

GROTH: When you started drawing from your father’s porn stash — now that would have been around ’40, ’41, ’42 — I assume that wasn’t hardcore porn, it was cheesecake-type stuff.

THORNE: Oh no, I was doing outrageously pornographic imagery; massive pudenda and giant breasts. I kept it stashed in the attic. One dark day, they vanished. Maybe my chum Fudder took them. Could be my brother was the culprit. The mystery remains unsolved to this day.

I did homage to those drawings at the end of Iron Devil: Devil’s Angel. There’s a phantasmagoric scene where Roxy is transformed while she’s being impregnated by the Devil. Her breasts and genitalia become grotesquely enlarged.

GROTH: When did you come under Alex Raymond’s spell?

THORNE: Raymond became my idol the moment my father got a subscription to the New York Journal American and I discovered Flash Gordon. That was it. He drew great ladies. I can remember the moment when I had my epiphany. It was an otherworldly scene from the Waterworld of Mongo featuring Flash and Dale. I started copying Raymond’s stuff. Young aspirants shouldn’t ashamed to copy their favorite cartoonist. It’s a great way to learn, to a point. Eventually, you have to become your own man or lady.

Back in the early '40s, there was no such thing as the excellent Kubert School here in Jersey. There were very few books on the subject. I did have a copy of Draw Comics! Here’s How, by George Carlson. I practically wore it out. At age 13 I got a copy of Figure Drawing For All It’s Worth by Andrew Loomis. I near wore that one out as well.

During my three years at the Art Career School, I enjoyed a number of epiphanies; I discovered the great magazine illustrators of the ‘40s in a great book titled Forty Illustrators and How They Work. Al Parker, Coby Witmore, Dean Cornwell, John Ganham, Matt Clark, Harvey Dunn…I could go on and on. The young Raymond was influenced by Matt Clark among others. You’ll find where Raymond got his vision of Mongo in the marvelous works of Franklin Booth.

GROTH: Did you ever meet Alex Raymond?

THORNE: I wrote Raymond a letter after I was hacking away at Perry Mason for several months. I excoriated myself, pleading forgiveness for copying his style. To my surprise, he wrote back. The letter had the tone of a moral scold. I was justifiably reduced to the size of a repentant pickle. Yes, I did meet Raymond; it was at the annual National Cartoonists Society outing at Fred Waring’s palatial estate on the Delaware near Stroudsburg, Penn. I, the feckless lick-spittle, a mere boy, really, approached The Great One with trembling chin. The minute or two he shared with me oozed with condescension. After that it didn’t take much urging from Devlin to move on from the Raymond style. Gary, I ask you: if he was The King, what of noblesse oblige? Isn’t royalty obliged to act with compassion?

GROTH: Raymond’s great talent allowed for such pomposity.

THORNE: The one who truly carried the Raymond torch was Al Williamson.

GROTH: Yes, right.

THORNE: I discussed the Raymond thing with Al on several occasions. He also felt the burden, and he carried it for decades after I long dropped it. But no one did Raymond like Williamson. It was great stuff.

GROTH: So you were focused on illustrators, not comic-book artists.

THORNE: True, Raymond’s stuff was highly illustrative and I went forth holding Raymond’s banner. I was never enamored with Caniff’s drawing style, but I loved his writing. I was in awe of Foster’s Prince Valiant. You’ll see his influence in The Illustrated History of Union County, which is a mixture of Neil O’Keefe, Raymond and Foster. Incidentally, my royalties from The Illustrated History have been very beneficial to the fund to restore the historic 18th century Frazee house here in town. So I can’t thank you guys enough for publishing in book form the stuff I did as a teenager.

GROTH: Caniff had a lush style and a number of strong women characters like the Dragon Lady.

THORNE: But they looked like cartoons to me. Raymond’s women looked real and sexy. Raymond was the primary influence, along with the great illustrators of the period. The Kirby style I could never take, I couldn’t look at the stuff. I worked in the Raymond manner into the mid-’’50s. In '52 I showed my portfolio to Sylvan Byke, the editor supremo of King Features, located then in New York City. He saw my Raymond style and to my amazement handed me the daily and Sunday of the Perry Mason newspaper strip. I was this 22-year-old kid. It went on for over a year and nearly killed me. That’s a lot of work. I was making $350 a week in 1952, which was a hell of a lot of money in those days. We bought a house and a brand-new yellow Chevy convertible.

GROTH: That’s probably the most money you’ve ever made in your life, relative to cost of living.

You were working away from the Raymond influence in the mid-‘50s.

THORNE: Yep, I was developing my own style under the pressure of Harry Devlin, who was a great cartoonist. He and his wife Wende lived in nearby Mountainside. He became my mentor. Harry was the one that insisted that I become my own man and drop the Raymond style. So I was about 24 or 25 years old and I started breaking away from the Raymond look. When I got to Dr. Guy Bennett, which went on for six years — it was another grueling daily and Sunday — for the Lafave Syndicate, I had pretty much moved on from Raymond.

GROTH: Early on, I would say the artist you most resembled was Kubert.

THORNE: That’s the highest of compliments. Consider the fact that Joe’s dad was a butcher and mine was an elevator operator. Had we been born into the bourgeoisie we’d have probably been sent to Europe to study oil painting. That sociological observation was a point that Gil Kane made years ago, and he was probably right. Gil would, without the slightest provocation, expound on any subject.

GROTH: Now in the ‘50s Toth was, ironically, probably influenced the most by Caniff.

THORNE: Alex was inspired mostly by Sickles, as was Frank Robbins of Johnny Hazard fame. Years ago I met Robbins at a Cartoonist Society dinner. He claimed he’d never heard of Sickles, which was the whopper of the century. I knew Sickles through Harry Devlin. Toth worshipped Sickles. It’s well known that it was Caniff who adapted Sickles’ technique that produced the mature Caniff style.

GROTH: Right, and of course there was Crane.

THORNE: Ah, the great Roy Crane. He influenced a whole generation of aspirants. Meanwhile, Toth heard that I had socialized with Sickles at the Devlins’ famous soirees and wanted Sickles’ address and phone number. Harry obliged and I passed the info to Alex. Toth wrote Sickles a couple of letters and tried to call him. Sickles thought Alex was a nut case. He refused to talk to him and never answered any of his mail, which got Toth really pissed off. Alex writes me a sulfurous postcard saying “I wrote him and I’m not hearing anything, and when I call he won’t talk to me.” It’s like my fault that I gave him his address.

GROTH: [Laughs.] When in fact Sickles should have been pissed at you.

THORNE: [Laughs.] I doubt he knew how Toth got his address. In my small collection of original art, I have a dynamite Sickles illustration from the old Life Magazine. He presented it to me at one of the Devlin parties.

GROTH: Approximately what year would that have been, when you gave Toth Sickles’ address?

THORNE: Fifty-seven. Fifty-eight.

GROTH: OK. That late.

THORNE: I don’t think Toth had come to his Zorro yet, but he was doing some great stuff.

GROTH: What was Sickles doing in the late ’50s, mostly illustration?

THORNE: He did product and magazine illustrations. I recall him doing the Battle of Gettysburg for Life Magazine. A big double-page spread of Pickett’s Charge. It was sensational. In a social situation, both Sickles and Caniff seemed preoccupied. That’s OK; they were two of the great craftsmen of that time. Harry and Wende were gracious hosts at those gatherings at their fabulous home in Mountainside. What can I say? Marilyn and I were lucky to be on the guest list. Incidentally, we named our oldest daughter Wende, after Dorothy Mae Wende, Harry’s glorious and loving bride. She was an extremely gifted painter and poet. We sorely miss them both. I can’t believe they’re gone.

GROTH: How often did you visit the Devlins?

THORNE: Maybe a couple of times a year until I started with Playboy, then things cooled off. Wende had a thing about Playboy.

GROTH: Tell me more about Harry Devlin. He was an illustrator and a painter, wasn’t he?

THORNE: Harry was a good painter, but a great cartoonist. I never quite forgave him for leaving the cartoons behind to become an architectural illustrator and writer. He felt it had more prestige. Harry always wanted to be “official,” and cartooning certainly isn’t official. He and Wende did a whole bunch of wonderful children’s books together: she wrote and he did the illustrations in his inimitable cartoon style. He had brought American cartooning to new heights, and then he walked away from it.

GROTH: What are some of the titles they produced?

THORNE: Old Black Witch, which was re-titled Old Witch in subsequent editions, A Kiss for a Wart Hog, and The Knobby Boys to the Rescue, to name a few.

GROTH: Is Mountainside near Scotch Plains?

THORNE: It’s about six miles west of here.

GROTH: How did you get to know him, was he a friend of your father’s?

THORNE: [Laughs.] No. Harry’s accountant lived across the street from Marilyn in Elizabeth. The accountant set up an appointment. I showed him my portfolio and he gravely told me I should go into another line of work. I was 18 at that time. So with moist eye I left, but I had the fire in the belly. Nobody could have dissuaded me, because you know if a kid’s going to do something, he’s going to do it. And when I have the opportunity to look at a young person’s work I’m always encouraging. I always find something positive. After the meeting with Devlin I developed The Illustrated History of Union County. When it began appearing as a daily feature in the local paper, he called me. It was an apology of sorts. He wanted to see me again, so I returned, and from that point our friendship grew, and it was wonderful.

GROTH: You were gravitating toward illustrators and toward the more illustrative comic-strip artists.

THORNE: Right, we’re not talking cartoons. I had seen some of Heinrich Kley’s line work. Kley could be wickedly funny. Think naked ladies ice-skating with alligators! That’s my kind of guy.

GROTH: We’re going to have to talk about that later, because it seems to me that you’ve moved more toward cartooning in the last 20 years or so.

Young Man with a Horn

GROTH: It sounds like you had two artistic passions in your youth. One was drawing and the other one was the cornet?

THORNE: Yeah.

GROTH: Tell me how that started, when you started playing the cornet?

THORNE: My first horn was a used silver cornet. Then came the trumpet, a brand new Martin Committee model. I took lessons from Fudder’s old man. The Morbachs lived down the street. A bunch of my high-school chums formed an 18-piece swing band. I played first trumpet and did some of the ride solos. We were doing mostly Miller and some Kenton. The band got a lot of gigs in the ‘40s, mostly proms and weddings. Our signature job was the four-night gig at The Crystal Ballroom in Keansburg N.J.

GROTH: You had your own swing band.

THORNE: It was Bob Ulbrich’s band; he took the name Williams as leader. His father was a lawyer. He bought the orchestrations and the music stands and got us going. After several years, Bob left the band behind and went on to become a successful lawyer like his dad. But The Bobby Williams Band was his bliss; it was his sweet spot. The original of the big illustration of the band that’s in The Crystal Ballroom is hanging over the head of his bed! [Laughter.] He loves to reminisce about the old Bobby Williams days. Recordings of the band survive, and they still sound pretty good. Harlem Nocturne was our theme, and man, that sounds really good. Bobby sure was great on those passages on the alto sax.

GROTH: We could include a CD with the issue.

THORNE: [Laughs.] Great idea! One of my favorite band stories involves the 50th anniversary of the class of 1947. Bobby brought along a tape of four or five of the songs we had recorded, and the DJ played them on the big speaker array. Voilà! The class of 1947 danced to the music of Bobby Williams Band yet again. We had lost a trombone and maybe a trumpet. But principally, most of the band members were there, all white-haired old men bent with age and long in tooth. But it was wonderful.

GROTH: What got you into jazz?

THORNE: Well, I loved the black musicians. Cootie Williams and Louie Armstrong, they were doing it for me. Everybody was listening to Harry James, and I preferred the black jazz performers. Dizzy Gillespie totally blew me away. I was a huge fan. And what a showman! I wish I’d heard Diz live just once.

GROTH: There was Coleman Hawkins and Ben Webster.

THORNE: The horn men; that’s where I was at. Those guys really inspired me.

GROTH: Were a lot of your friends into jazz?

THORNE: Yeah, we had a nucleus of musicians. None of them were interested in art. They were only into the music. And we would jam. When we started playing gigs we could make 10 or 15 dollars a night, which ain’t bad, but we were pretty good and getting better all the time. We played the Rahway Youth Center, often in small and large groups. Then I became enamored with Bobby Hackett. He wasn’t black, but I loved his style. If you’ve heard his String of Pearls CD you’ll get the message.

GROTH: How old were you when you were in the band? Were you 14…16?

THORNE: The band got going when I started high school in ‘43. I was 13. But I had the art thing going, and I was something of an amateur magician. I recall being mostly in the art and music rooms all through high school. I did manage to pass two years of Algebra, which considering my dazzling incompetence in math, amazes me to this day. John Cooper was the art instructor at old RHS. I had him in my freshman and sophomore years. John’s tutelage, warmth and interest were an inspiration. I owe my chosen path in life to John. Last summer is coming a letter. John Cooper is 95 years old and lives on Harstine Island off the coast of Washington State! I hadn’t heard from him in 60 years. He got a copy of The Crystal Ballroom and writes me the letter. It was a rave review. We’ve been corresponding ever since. My hambone acting on the Playboy Channel show, and all those Wizard and Red Sonja shows stems from the fast and funny high school Art Club shows that John wrote and directed. He was an accomplished magician and taught me the basics. I did some shows and invented and manufactured several magic tricks. “Thorne’s Wobbly Wand.” You can still buy ‘em online.

GROTH: Do you still get royalties?

THORNE: I only manufactured a couple of hundred for Max Holden, who owned a magic shop in Manhattan. He paid me for the batch and that was it. I moved on. Somebody took the design and produced the wands; but they kept the name. Recently I attended a Magician’s Roundtable and by George, one of the magicians used the Wobbly Wand in his act!

GROTH: At some point you had to choose between music and art.

THORNE: Enter Maggie Burke. She became the art instructor when John left Rahway High in my junior year. Understand that I was a pretty good on the horn at age 17. I was playing with Bobby Williams and Bobby Kaye’s big swing band out of Perth Amboy, N.J. Kaye, his real name was Koch, was a fantastic trumpet man, but the best was Morris Nanton on piano. Google him, Gary, he’s got a bunch of CDs out there. Howard Kelly, the music director at Rahway High, was encouraging me toward a career in music. He took me in to Manhattan to meet Ray Conniff. Conniff was staying at a seedy hotel in midtown. It was a dreary experience. His room was a mess, and he was with some dame who looked like a drawing by Toulouse-Latrec. Here was the great Conniff, and the scales are beginning to fall from my eyes. Kelly was to sit in with his band that night on the Starlight Roof of the Hotel Pennsylvania. I went along and played in the trumpet section for most of the evening. I started scabbing jobs at 17.

GROTH: There were some legendary broadcasts from the Starlight Roof.

THORNE: Yeah, most of the greats of the swing era played there. What a thrill it was to play The Starlight Roof. I was on top of the world!

GROTH: So you really had a choice to make: music or art.

THORNE: That’s where Maggie comes in. I’m about to graduate from Rahway High and Maggie comes to our house one afternoon and says to my parents “This boy has to go to art school!” She would arrange for a half-tuition scholarship for the first year of a three-year course at the Art Career School atop the iconic Flatiron Building in lower Manhattan. There was much serious pondering and family discussions. Probably the visit to Conniff’s hotel room was the deciding factor. I started at The Art Career School in the fall of ‘47.

GROTH: Did you continue with the music while in art school?

THORNE: Hell yeah, but I had to cut back. I couldn’t practice as much and I was losing my lip. The summer of ‘47 was also pivotal in another most important aspect. I attended the Roselle Band and Orchestra School and met Marilyn, my bride of 56 years, but it was 60 years ago that I first saw her, a beautiful blonde, playing first trombone in the school’s symphonic band. It’s true, Gary, I married her for her embouchure! I was in the trumpet section, also the band librarian. I’d adoringly give her extra copies of the first trombone music for Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony. I was in love. Gary, what can I tell you? It was kismet!

Marilyn was first chair in the All State Band for two years and then attended Julliard. She’s been a professional musician most of her life. Marilyn has played the Mighty Wurlitzer at the nearby Willow Grove Presbyterian Church for 53 years. She has dozens of private piano students, and has been at it for over 30 years. My bride — all cartoonists’ wives are brides — is a person of faith, while I remain an unregenerate heathen. We are the odd couple. She is also the understanding angel. After all, there I am hamming it up on the Playboy Channel and canoodling with Sybil Danning and porn diva Tyffany Million.

GROTH: Does Marilyn still play the trombone?

THORNE: Alas, it’s been gathering dust in the attic for many years. She plays just the organ and piano. We attend a lot of concerts, mostly classical orchestral and choral works. We’re into chamber music as well.

GROTH: No jazz?

THORNE: I’m content to hear the jazz greats on CD. I have a whole bunch. Getting back to ladies, naked or otherwise, I think the cello is the sexiest musical instrument ever devised.

GROTH: That’s right, and it’s almost as big as a woman.

THORNE: Playing the cello requires the musician to hold the instrument between his or her legs. When it’s a dame sawing away I’m distracted, even with the Boccherini Cello Concertos which are my favorites. I’m sitting there thinking, “Is she wearing any underwear?” Some years back Charlotte Moorman concertized playing the cello topless. Had I attended one of her recitals I would have died! [Laughter.]

The late cellist Jacqueline Duprey was absolutely fantastic. She was blonde and sexy, even when she wasn’t playing the cello. I’m a sucker for a female musician.

GROTH: Wouldn’t jazz have been considered slightly risqué or disreputable at that point, I mean among the white, middle class?

THORNE: Well, yes, and my father was not friendly to black people. He was actually frightened of them. Pop didn’t have a robust musical aesthetic; a Sousa march and “Roll Out the Barrel” were all the same to him. I’d play the records in my room and keep the albums out of sight. When you’re in your early teens, you’re so impressionable. You carry that stuff with you for the rest of your life. I mean, that’s my music. Forget rock and roll and everything that followed. It’s like the matrix has been set and that’s what it’s going to be for the rest of your life. I gather you’re a jazz enthusiast.

GROTH: I am indeed, and especially of that period.

THORNE: Now, when did your interest begin?

GROTH: Well I didn’t start until the late ‘70s, and the guy who really helped me figure out what the hell was going on and what to listen to was Gil Kane.

THORNE: Ah, the professor himself!

GROTH: [Laughs.] That’s right.

THORNE: He always dressed like he was going to a party! [Laughter.] But he was brilliant. With the slightest encouragement, he would deliver a tutorial on practically any subject.

GROTH: Yep. Well, he was my best friend for over 20 years, and of course, he was your generation, so he was listening to the same stuff that we’re talking about. So I asked him where to start, what to listen to, and he would just reel off the names. And you couldn’t get a better tutor.

THORNE: Yeah. Think of it, my whole generation in the craft is gradually departing this mortal coil. Exeunt omnes is a Latin phrase used in theater meaning “exit all.” I mean, poor Al Williamson is battling Alzheimer’s, Gray Morrow’s gone, and now Toth, they’re falling left and right. Dedini’s kaput as well. By the gods! He was good! When Moon started in Playboy it was of the highest order that I was in there with guys like Dedini. Did you finish the Dedini book?

GROTH: It’s at the printer.

THORNE: Oh boy, it’s gotta be gorgeous. Michelle Urry was excited to work with you on that.

GROTH: Well, I’m sure I was equally excited to work with her.

THORNE: She’s a sweetheart. Has she ever been good to me. I can’t tell you, Gary.

GROTH: You will tell me.

THORNE: [Laughs.] We’re getting ahead of ourselves.

GROTH: OK, now let me skip back again. Did your parents encourage your artistic inclinations?

THORNE: Very much so. Yes. They were totally supportive of my aspiration to play music or do the art. But I must say, the music teacher would call and encourage, so they got the word from the school that, “You should get him a better trumpet, and he should be encouraged,” and so forth, which they did. And there was Maggie Burke pushing me toward the art career. At the graduation ceremonies of the Class of ‘47, I was 16; I was presented with awards for outstanding progress in both art and music.

GROTH: How long did you stay with Morbach as your music teacher?

THORNE: I switched to Harry Mandel, an excellent teacher and a great guy who thought I was going to going to be the next Harry James. Not. Diz maybe, if only in my dreams. But I practiced regularly. That’s what moved me along. It’s the same with drawing. You’ve got to keep at it.

GROTH: It sounds like you were living in a sensualized aesthetic environment.

THORNE: I was a dirty young man that loved jazz, but I had one foot in the classical genre.

GROTH: You say you’ve been with Marilyn for almost 60 years; how old were you when you married?

THORNE: We were both 20, our parents had to sign for us.

GROTH: You married at 20?

THORNE: Yep. Ours was and is a house of music. Marilyn has her music studio downstairs, and I’m upstairs in my studio drawing sexy women while recalling those great jazz musicians of that early period. It’s a time machine. When I’m listening, I can feel the mouthpiece on my lips trying to imitate Mugsy Spanier and Cootie Williams growling away. There was no double-tracking in those days; they were just up there wailing. It was just straight out the end of the horn.

GROTH: Did you like Artie Shaw?

THORNE: Yeah, yeah, sure. He was influenced greatly by the black musicians. And Goodman, of course; and what a technician he was.

GROTH: Do you have siblings?

THORNE: I had a brother George, yet another George Washington Thorne, named after my dad. He passed seven years ago.

GROTH: Would that have been an older brother?

THORNE: Yes, he was seven years older than me.

GROTH: And what was your relationship with him like when you were growing up?

THORNE: He played the saxophone, but we never played together. George was not musically gifted. He played in the high-school band and that was it. Then we went our separate ways. In the last 20 years of his life we became very close. It was wonderful, but I don’t think he ever figured me out. He was a businessman, a furniture salesman, a straight arrow. He had smoked cigarettes since his teen years and died of lung cancer. I still miss him.

SCHOOL FOR SCANDAL

GROTH: What was your school like?

THORNE: Art Career School?

GROTH: No, I mean elementary and high schools.

THORNE: Back then there were no “gifted and talented classes.” I think it’s stigmatic. They promise them too much. Here’s a kid that’s told he or she is gifted and talented and wakes up 10 years later in a dead-end job. Marilyn was, and is, extremely gifted and talented. But the teachers didn’t single her out, they encouraged her. Both of Marilyn’s parents were excellent musicians. Her father was her first music teacher. He taught her the piano, trombone and organ, which she plays with her hands and feet. How the hell she does it amazes me. [Laughter.] How Diz did it still baffles me. When I first heard Gillespie I damn near gave up and switched to the kazoo. [Laughter.] If it’s easy for you to do, that’s a good definition of talent. Diz played with such fury and ease, which is an oxymoron, but it fits.

GROTH: When did you gain an interest in writing?

THORNE: As a kid I read Great Expectations, which had quite an impact. I read Twain in between listening to Jack Armstrong, All American Boy. And my father had a copy of Life Among the Nudists, which I read vociferously. [Laughter.] It featured photos of nudists cavorting around in an Alpine setting. But the nudists were so far away that they looked like frolicking ants. If you looked at them with a magnifying glass, all you could see were a zillion little dots.

GROTH: You were born in a far different time.

THORNE: There were few distractions. We had radio, but no television. Think of it. No iPods. No Internet. No cell phones. For the average kid in those days the only thing that was in any way stimulating from an erotic standpoint was the ladies-underwear section of the Sears catalog. For me there was my father’s collection. It was a quieter time. I don’t envy the kids today, because there are so many distractions. There are too many things that they’ve got to have. They’re constantly being bludgeoned with commercials, and they’re promised too much. To put kids on a “gifted and talented” track is to stigmatize them. They wake up a few years later in some boring job wondering, “If I’m gifted and talented, how come I’m stuck here?”

GROTH: Did you read any comic strips other than Flash Gordon?

THORNE: I read most of the strips in the Journal American’s comics section. And there was a rotating library of comic books and Big Little Books that were shared by [starts to sing] “that old gang of mine!” [Laughter.]

GROTH: Did you read the pulps?

THORNE: I had a few, but they weren’t included in the floating library. My childhood chums Fudder and the Decker kids weren’t into heavy reading. Some of the great writers of the 20th century wrote for the pulps: Bradbury, Burroughs, Lovecraft, even Tennessee Williams, to name but a few. One of my proudest early achievements was illustrating for the pulps. It was crap, but at least I was part of that wonderful world that was rapidly being replaced by the colorful world of comic books. Fabulous full-color paintings adorned the covers, which was a higher-quality paper. I went back to the offices of Fighting Western in the mid ‘50s. Mr. Barrow, the editor, was still at the helm. The company had switched from pulps to a line of cheesy girlie magazines. He remembered me mostly because I had custom-made my portfolio out of plywood. It had a hole in it and it looked like a zither. He didn’t remember that I was wearing slippers and pajamas. In the warmer months, I wore my pajamas to school.

GROTH: Hmm, I need to talk to you about that. [Laughter.] But before I do that, tell me more about Art Career School.

THORNE: In ‘47, the WWII vets were taking advantage of the GI Bill. It was tough to get in most schools, and ACS was no exception. I won a half-year scholarship in a competition and signed on as one of the custodians, which covered my first year’s tuition. I was the clean-up guy for the next three years. When all the kids left at 3:30 p.m. there I was with Richard Henthorne, each with broom and pail. I was lucky if I made the 5:20 to Rahway out of Penn Station. Henthorne was an opera buff. He taught me several arias from La Traviata. I still remember them. [Starts to sing] “Di Provenza il mar, il suol!” [Dissolves into laughter.] In the winter I’d get the mother of all colds and it would last until late March. I lived on Aspergum. If I missed the 5:20 I’d have to take the 6:10 which didn’t get me to the North Rahway Station until 7:00, then it was a mile walk to home.

GROTH: We had so much energy at that age.

THORNE: Yeah, at 76 here it takes you a little longer to do things. What I used to do all night it takes me all night to do! [Laughter.]

GROTH: Where is the Flatiron Building?

THORNE: On Fifth Avenue and 23rd Street. It’s a magnificent building. We were across from Madison Square Park. The corner of 23rd and 5th is unique. It’s always windy, I mean really windy. In the early part of the last century, naughty young buckos would gather on the corner to watch the breezes blow the young ladies’ long dresses in hopes of seeing their ankles, or a stretch of lower leg. The police would sidle up to the oglers and move them on saying “Skidoo!” That’s how the phrase “23 Skidoo” crept into our language.

GROTH: You were a busy young bucko.

THORNE: Make that naughty young bucko! [Laughter.]

GROTH: I mean with the school and the gigs.

THORNE: I preferred the music jobs with smaller groups, the pay was better. Marilyn often played with our sextet. It helped having a beautiful blonde at the piano.

GROTH: Did you dig the New York scene?

THORNE: [Starts singing] “I love New York in June, what about you?” Especially 42nd Street. It was godawful glorious in the ‘40s! Smutty wonderful. Ah those fabulously foul rundown movies theaters lined up one after the other. You could catch a matinee of Around the World with Nothing On, then drift over to Captain Harold’s Flea Circus, which was a 24-7 sideshow. Then there were the shoddy little shops that sold the nude pictures of ladies. I’m sure hardcore photos were available somewhere along the strip, but I never saw any in the ‘40s. That came later. But the nudie pictures were gloriously innocuous. I’m thinking Maria Stinger and Pat Hall, pneumatic goddesses of sweet innocence with their pubes airbrushed to oblivion. And the nudist colony movies, often hosted by Velma Zupre, a 300 pound virago, featured a variety of sports activities filmed in the buff. Volley ball footage was de rigueur for any nudist movie worthy of 42nd Street. In the late ‘50s came Show World on 8th Avenue. You could see Candy Samples strip naked, and then meet her, still butt-naked, for an autograph at no extra charge! Then live sex came to 42nd Street. Sordid subterranean theaters offered a steamy smorgasbord of fellatio, cunnilingus, and all the positions in the Kama Sutra; all for five bucks a pop. Then came Disney and ruined it all. Disney is the Devil! [Laughter.] Those shows are made for the tourist trade. Most are vacuous crap. Can you imagine, some show’s seats are getting $480 for front-row center. The average is around a hundred bucks a seat. I’ve seen a couple of them. Each time I shuffled out mumbling “What a piece of shit that was.” [Laughter.]

There were three of us in A.C.S., Hy Eisman, myself, and Al Kilgore. The Three Musketeers!

GROTH: How did you meet Hy Eisman?

THORNE: I met him in our first days at the Art Career School. We were in the freshman class. Hy was on the GI Bill.

GROTH: And you guys became friends?

THORNE: We did indeed. And he’s still a buddy. He’s now writing and drawing Popeye and The Katzenjammer Kids. He’s done Little Iodine and Smokey Stover, to name a few. He also ghosted Kerry Drake for quite a spell.

GROTH: Correct me if I’m wrong, but he turned into a real stylistic chameleon, didn’t he? He can do almost anything, from the more illustrative stuff to the more cartoony stuff.

THORNE: Hy’s an amazing talent. He’s been teaching at the Joe Kubert School since it started. Funny story: A few years ago Hy was in the Sistine Chapel in Rome. Florence, his effervescent bride, was with him. She’s very proud of Hy’s talent, so wherever they travel she wears a blazer with an enameled Popeye pin on the lapel. So, as all are in awe of the great Michelangelo ceiling, a guard approaches Florence, and in halting English whispers “Scusa, why you wear the Popeye pin, per favore?” She whispers back that Hy draws Popeye. In a thrice Hy is off to the side making sketches of Popeye for several of the attendants! [Laughter.]

GROTH: So why did you guys hit it off?

THORNE: All we wanted to do was comics. Al was also on the GI Bill. Art Career School was a three-year course in commercial art. They didn’t offer instruction in comics. That’s OK, because I suspect that you can’t teach art, or comics. Guide and nurture maybe. We need a better definition of “teach” here. Why, you may ask, why didn’t I go to the Cartooning and Illustrating School a few blocks east on 23rd Street?

GROTH: Why? I ask.

THORNE: Practicality. The theory was that I should get the basics in commercial art-techniques, so when I went around to get a job I would know how to do masking, frisketing and paste-ups — they don’t have paste-ups any more. Mechanicals — no more mechanicals — but I employ some of those commercial techniques in my stuff to this day.

GROTH: The School of Cartooning and Illustrating became The School of Visual Arts.

THORNE: The Cartooning and Illustrating School was started by Cy Rhodes and Burne Hogarth.

GROTH: Hogarth of Tarzan fame.

THORNE: Yeah. I attended a lecture by Rhodes and Hogarth years ago. It was boring beyond human endurance. [Laughs.] I never heard such pompous claptrap in my life.

GROTH: Burne took himself, and his art very seriously. What kind of artists was the Art Career School turning out?

THORNE: I hasten to add that A.C.S. was a small school. The graduates were mostly people who would go into advertising agencies, printing companies, publishing houses and the like. One graduate, Warren Aldoretta, became the art director of Kodak, and Charlie Long made it to the top as art director of New Jersey Bell Telephone Company.

GROTH: Talk more about the basics you learned.

THORNE: Well, we were taught the color wheel and the fundamentals of design. We visited the Metropolitan and studied the great paintings. Then you had the life classes; naked ladies, we’re back to that again! [Laughter.] Fortunately I never had to do a paste-up or a mechanical after A.C.S.

GROTH: You were lucky.

THORNE: Gary, I’ll tell you something. This is very significant. About 30 years ago I finally decided I had to have a card made. I never had a business card. So I had 500 made. And by last count I have about 480 of them left. [Laughs.]

GROTH: Fortunately, you didn’t end up in an agency.

THORNE: Yep, I’ve been in the craft for 60 years, working constantly. I had to; we started having kids, five in all. Incidentally we have 10 grandkids and three great- grandchildren. With all the naked ladies, we are a solid family. It’s really a G-rated act. I’ve saved a recent note from Michelle Urry. It’s one of the greatest compliments I’ve ever received. I quote: “Congratulations on your 55th wedding anniversary! You’re really an amazing person. For someone who is so quintessentially an artist to have this deep-seated and focused family life is great for we editors who constantly deal with the trials and tribulations of painfully bereft, lonely and disgruntled artists who cannot find their way. You’re an example for all of them.”

FIRST TIME IN INTIMATE LOVE

GROTH: Let me ask you this. You started going to Art Career School in ’47. At what point were you starting to draw for money?

THORNE: Before art school I was making a few bucks doing covers and inside drawings for The County Sportsman. The first comic-book work would have been at Standard.

GROTH: I thought the first comic work you did was Ibis the Invincible.

THORNE: I’m sure it was for Standard. I penciled “My Selfish Heart,” an eight-pager that ran in Intimate Love #7. Joe Archibald gave me the job. So we can thank Joe for getting me started. Dan Barry was freelancing at Standard about that time. Boy, was he good. He did a Flash Gordon that was just great; it was different from Raymond, but solid stuff. His brother Cy was at Standard as well. He went on to do The Phantom.

GROTH: There have been a couple of artists on that strip.

THORNE: My buddy Fred Fredericks did the Phantom Sunday page for several years. He’s been doing Mandrake for over 40 years. Boy, am I glad I didn’t sign on to something like that. [Laughs.]

GROTH: The history of comics is littered with stories like that; people who get into a rut and that’s what they do. Someone who refused to do that was Everett Raymond Kinstler; do you remember him?

THORNE: Yeah, he did Silver Tip at Dell when I was there in the early ‘50s. He worshipped James Montgomery Flagg. He did pen work in the Flagg style, it was great stuff. Ray left comic books to become a much sought-after portrait painter. He’s had commissions to paint several presidents.

GROTH: Do you know him now?

THORNE: Haven’t seen him in years. In the ‘50s, Hy Eisman and I visited his spacious studio in SoHo. Ray had painted a life-size portrait of himself and it was mounted in a gilt rococo frame that dominated the wall. It was great. Just before Flagg died, Kinstler brought him to a National Cartoonists Society meeting. Flagg was hanging on to Kinstler; the poor old guy was nearly blind and struggling along with a cane. Here’s a room full of drunk cartoonists trading bawdy stories and it’s like the mummy of Rameses II was being toted out of his tomb. Then a silence enveloped the room. As Flagg haltingly moved toward his seat, all the guys got up and applauded until he sat down. It was a wonderful moment. I think he died shortly after that. The mantle fell from Flagg onto the shoulders of Ray, and they were broad enough to carry the load.

GROTH: You did Ibis for Fawcett?

THORNE: Actually for Louie Ferstadt, who inked my pencils. It was his book for Fawcett. I call him Fierstein in Drawing Sexy Women. Some of the names in all my books have been changed to protect the innocent! [Laughs.] He taught at Art Career School. Old Louie was an unregenerate Bolshevik.

GROTH: How old would you have been when you did Ibis? Were you in the Art Career School?

THORNE: I started at 17, in ‘47, and graduated at 19, in ’49.

GROTH: You started early.

THORNE: You think I had an early start? Joe started when he was about 12.

GROTH: Kubert?

THORNE: Yeah, the great Kubert. And he’s better now than when he was flying through the decades doing Sgt. Rock and all that great stuff. Joe still mourns his old Norman Maurer. They worked on the first 3-D comics together. We would go every year to the Kubert School graduations. Joe would be saying that Norman was the more gifted of the two. Not. Joe had it over Normy in spades. Maurer’s uncle was one of The Three Stooges and went on to produce their movies.

GROTH: Tell me how it worked, and tell me how you hooked up with Ferstadt, first of all.

THORNE: I just started going around showing my stuff and voilá! This little pigeon-chested guy with the genial smile gave me work. When I think about that early passage, it seems like I was living two lifetimes. Fortunately, since those early days, I haven’t had to hustle for work. It comes to me.

OF HUMAN BONDAGE

GROTH: In Drawing Sexy Women, you write about a woman named Bonnie.

THORNE: She was one of the nude models for the life classes at the Art Career School. Bonnie was an auburn-haired beauty with a body that could raise the dead. I refer you to the cover of this magazine. [Laughs.]

GROTH: How old was Bonnie when you knew her?

THORNE: She was in her early 20s and delightfully uninhibited. Bonnie also modeled for Louie and a lot of other artists and photographers around The Big Apple.

GROTH: And she got you involved in the girlie-magazine and bondage scene.

THORNE: I penciled Ibis in Louie’s studio at Union Square. Bonnie was the model, so I got to know her personally. No, I didn’t get laid! [Laughs.] I remained a virgin until I married Marilyn.

GROTH: Jesus, how did you manage that?

THORNE: Six years ago we were celebrating our 50th wedding anniversary at a family event. I was sitting on the patio polishing off my second martini. Our three sons-in-law joined me. During the conversation, I mentioned that Marilyn was the only woman I had ever slept with. There was an incredulous pause. They laughed! They didn’t believe me! [Laughs.] Ingrates! How sharper than a serpent’s tooth!

GROTH: Well, it is a little astonishing.

THORNE: That’s the dirty little secret of my act. My act is G-rated, but it looks dirty. I’m perfectly happy with Marilyn. I owe it all to her love, support and understanding, and she gets better-looking every year!

GROTH: You were telling me about your platonic relationship with Bonnie.

THORNE: Yes, we discussed Platonic and Aristotelian philosophy while I drew her tits.

GROTH: Did Bonnie pose for Jugsy Malone?

THORNE: No, Jugsy sprung full-blown from my feckless brow; albeit Bonnie was an inspiration. A dead man would’ve been inspired by Bonnie. I again refer you to TCJ cover. In reality, the Jugsy half-pager was crude juvenilia. It only lasted four issues.

GROTH: I understand that Bonnie introduced you to the bondage czar Irving Klaw.

THORNE: I’d visited Irving’s establishment several times before meeting its fabled proprietor. It was a scruffy little shop in the shadow of the el on 13th Street in lower Manhattan. Long and narrow, it beckoned hapless hordes from the antipodes. What resembled a bar, complete with stools, ran the length of the store. Nervous hopefuls stood two-deep anxious for the opportunity to pore over the thick loose-leaf binders that displayed samples of Irving’s colossal inventory of bondage photos.

GROTH: Bettie Page and …

THORNE: There was Roma Paige and Maria Stinger along with Bunny Pope and Lynn Davis. There were offerings other than bondage on Irving’s menu. Consider the Junoesque Irish McCalla — whatta pair she had! [Laughs.] He had a binder devoted to strippers: Sherry Britton, Margie Hart, Tempest Storm … I’m beginning to hyperventilate! [Laughs.] And to think that now they’re all little old white-haired ladies.

GROTH: In Drawing Sexy Women, you have a hilarious description of meeting Irving Klaw and then a subsequent shooting session with Bonnie and Bettie Page at the Chelsea Hotel on 23rd. You described Irving Klaw as looking like a waiter from Smith and Wollenski’s, which I thought was just perfect.

THORNE: [Laughs.]

GROTH: You were such a devotee of porn and there was the allure of women, I don’t understand why you weren’t promiscuous in your youth.

THORNE: I was whacking the willie so much, I didn’t have anything left.

GROTH: Right. So tell me about Irving Klaw and his office; what it was like?

THORNE: I refer your readers to page 36 of Drawing Sexy Women. They’ll note that Klaw is holding my homemade portfolio in the shape of a zither! [Laughs.] I was never into bondage, so I backed off working for Irving. I was producing the Illustrated History and the pay was better than what Klaw offered. I was getting 25 bucks a pop for the daily feature in the local paper. It ran through 173 issues. A hundred–twenty-five bingos a week was a lot of money back then.

GROTH: You met Eneg in Klaw’s office.

THORNE: Ah, yes, he was the Thomas Kincade of bondage art! [Laughs.]

GROTH: Kincade, “The Painter of Light.”

THORNE: The painter of crap. I can’t stand that treacly shit. Incidentally, if you had a pristine collection of Eneg bondage art, you could make a fortune on eBay.

GROTH: The shooting session, both Bonnie and Bettie were there, right?

THORNE: Bonnie invited me to come to the shoot at the fabled Chelsea Hotel. It was just a block or two east of the Flatiron on 23rd Street. Bettie Page? Let me tell you; here I am in the same room with the primary initiator of a hundred seasons of fevered sleep. That alabaster skin, those raven tresses! She drove me to deliriums of self-abuse! [Laughter.] I had a modest gathering of her nude photos in my private collection. But a scoundrel with an airbrush had crudely obliterated her pubes on the master negative leaving the print with a pasty swath that resembled dried buttermilk. One of the spin-offs of the sexual revolution was [the fact that] that same guy, now bent with age, using that damned airbrush, re-established a dubious reproduction of her furry mound. [Laughs.] Bettie Page? Let me tell you; before my eyes, the goddess nonchalantly undressed, and there, like the Holy Grail, was her actual fully upholstered bush. Was I hearing a choir of angels? It was a seraphic bombo, so why not a host of singing seraphim?

GROTH: There was some tension between Bettie and Bonnie at the Chelsea, as I recall from your memoir. What happened to Bonnie?

THORNE: Last seen in the arms of the wrestler Gorgeous George in the lobby of the Chelsea after the shoot. I never heard from her again.

PRIVATES ON PARADE

GROTH: OK, you got the Perry Mason strip in 1952. Who wrote the scripts, and how did you get them?

THORNE: It was written by a staffer at William Morrow, the publisher of Earl Stanley Gardner’s books. I was working with Thayer Hobson; he was the head honcho at Morrow. He was a great bear of a man. My god, he looked like Baal, but he was a gentleman — Baal playing the cello! He was wonderful to me. Anyway, Hobson’s secretary would send me the scripts and I delivered the finished strips to his office in downtown Manhattan every Friday.

GROTH: So you didn’t have any contact with King Features after Sylvan Byke gave you Perry Mason?

THORNE: None. King syndicated the strip and Hobson did all the rest. Hearst, William Randolph, that is, who owned King Features, was a good buddy of Earl Stanley Gardner. That’s how Perry landed in the newspapers. When old man Hearst died, the powers that be at King killed the strip, which saved my life, because drawing Perry was killing me.

GROTH: How so?

THORNE: I would get up Wednesday morning, and work straight through to Friday without sleep. Then Marilyn would drive me into Manhattan while I slept on the back seat. When we arrived at Morrow, Marilyn would wake me and I’d slog up to Hobson’s office with the strips. Producing a daily and Sunday single-handedly is a man killer. I was lettering the strips and coloring the Sunday page as well. Marilyn began to be concerned for my health. It taught me a great lesson.

GROTH: Which was?

THORNE: Which was: What’s it all about? I could have died of a heart attack. It remains a trophy of my youthful passage; I mean for a kid that age to be doing a strip syndicated by King Features is almost better than bedding Bettie.

GROTH: Were you in the service during the Korean War?

THORNE: Had the 306 Special Service unit been activated, the Chinese wouldn’t have bothered to cross the Yalu River.

GROTH: What was the 306 up to in the early ‘50s?

THORNE: Hardly anything! [Laughter.] No, actually we were an entertainment unit based in Manhattan on 43rd Street. I played trumpet in the pit band for a musical developed by the unit. My oldest buddy Bob Ulbrich, aka Bobby Williams, played alto sax in the band. We toured army bases with a show. Yes! [Laughs.] We were traveling players just like with “Ramballock” in Nymph, but our show was “Magee.” [Starts singing “Magee, oh what a town it will be …”] I also designed the sets for the show. Actually, several guys in the unit who went on to fame. Everybody knows John Cassavetes. I loved his acting; he was really good in “Magee.” Following his career, I felt he was a better actor than director. Ever see Mikey and Nicky? It’s great. John’s wonderful. His buddy Peter Falk is in it too. He’s a marvelous actor. Elaine May directed —

GROTH: [Interrupting] You didn’t like Faces and Shadows?

THORNE: Sheer imposture. Unfathomable tedium. [Laughs.] Sorry, John, wherever you are!

We also had Joe Layton in the unit. He went on to become a well-known choreographer. Bambi Lynn’s brother was in the troop as well. Bambi was a beautiful dancer in the early days of television. There were excellent puppeteers, dancers, costumers, singers and musicians in the old 306.

GROTH: You must have been doing Perry Mason when you were in the 306.

THORNE: The Perry newspaper strip was waltzing off to limbo as I joined the Army Reserves. Perry would return to TV some years later. I’d be dead if I had to do a daily and Sunday and be a weekend warrior at the same time. With it all, Marilyn and I were starting to produce kids. All of this, and then the 306 was off to Fort Wayne to do the show, and then back up to Pine Camp in Watertown, N.Y., and then back in Manhattan. Each summer, the 306 did two weeks at Pine Camp, which has since been renamed Camp Drum.

PLAYING DOCTOR

GROTH: What happened after Perry?

THORNE: I slept for two weeks! [Laughter.] Then I went over to the Dell offices in Manhattan. They had been publishing all types of magazines since the ’20s. Dell farmed out the comic production to Western Printing located then in Poughkeepsie, NY.

GROTH: Who did you deal with at Dell?

THORNE: Well, the head honcho was the late George T. Delacorte Jr. Dell, the name of his company is a diminutive of Delacorte, which is funny because that wasn’t his real name, it was a simple Jewish name and he changed it to G. T. Delacorte Jr. He even added the Jr.! [Laughs.]

GROTH: Did you meet him?

THORNE: No, I dealt with Ann Destefano and Dick Small. Dick Small gave me a Flash Gordon coloring book to illustrate, followed by Flash Gordon, Jungle Jim, Green Hornet, and the Tom Corbett Space Cadet books. I did two movie adaptations: Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea, and Moby Dick. It was a tough passage because I was making a third of what I got for Perry Mason. We had bought a house and a brand new Chevy convertible with the Mason money.

GROTH: You took over the Dr. Guy Bennett daily and Sunday from Jim Seed in ’57.

THORNE: Bennett was the poor man’s Rex Morgan M.D. So I was back doing a daily and Sunday strip for the LaFave syndicate. It was something I swore I’d never be involved with after Perry Mason, but I was turning the stuff out a lot faster in my own developing style.

GROTH: Tell me about LaFave.

THORNE: Art LaFave was a big buttery man with a snaggle-tooth and a voice like B.S. Pulley. When I signed on he was still syndicating Napoleon and Uncle Elby, done by the great Cliff McBride. It made Art a rich man, but he was having a hell of a time getting the strips from Cliff, who had a drinking problem. I visited him in Cleveland and he delivered this long jeremiad about McBride and his boozing and how difficult it was to get the strips. On many occasions Art had to cut and paste to create a new gag from the published stuff. While there Art gave me an original Napoleon daily from the first week of the strip’s long run. It’s a fabulous piece of pen work.

GROTH: Hang on to that one!

THORNE: I keep it in a safe, along with a Sullivant and my cover for Red Sonja #1. Recently I sold a Moonshine and a Herriman topper through Heritage Auctions. When I told the contact at Heritage that I was offered 10 grand for it, he said he could get me a lot more than that. Gary, I was paid a hundred seventy bucks for it back in the ‘70s.

GARY: You said you were working faster in your own style.

THORNE: It was still a killer, but Art dropped the Sunday page after about six months. Doing just the dailies gave me time to pick up some commercial illustration work and spend more time with the family. We had three kids at that time. We soon added two more to our brood.

GROTH: Now, what did you do when Dr. Bennett ended?

THORNE: By late 1960, the list of newspapers that ran the strip had fallen below 20. The end was near, there were few vital signs, and emergency measures were needed. So Art changed doctors. He got a second opinion! [Laughs.] Art replaced Dr. Mike Petty and found another MD to write the script. He phased out Dr. Bennett and changed the strip to Dr. Duncan; Dr. Douglas Duncan! That dumb name was the death knell.

The new writer soon abandoned ship, and I wrote the last six months of the strip. I had written The Illustrated History of Union County, but this was different. It created a thirst in me to write my own material. That opportunity didn’t come along until years later with Ghita of Alizarr, and all that followed.

GROTH: OK, what happened after Dr. Duncan?

THORNE: I switched to commercial illustration for several years then drifted back to comics with Mighty Samson, among others, at Gold Key. Incidentally, in 1960, the management at Western Printing decided to start their own comic-book line, hence Gold Key was born. They had a good start under the leadership of Matt Murphy. Matt’s a great guy and a damn good editor. He landed the Disney material for Gold Key, which was a big boost to the new line.

GROTH: After Mason, you returned to comic books. What was the pay rate in the ’50s?

THORNE: Thirty-five bucks a page. What I get for a single-full-page gag at Playboy is more than two 24-page stories I did way back then.

GROTH: How did it work? Did they just hand you a script?

THORNE: Yep. I think I probably still have some scripts from that era.

GROTH: Do you know who wrote the stories?

THORNE: I recall Paul S. Newman writing some of the Dell and Gold Key scripts, and there was the great sci-fi author Otto Binder who wrote Mighty Samson.

DOING IT ALL

GROTH: You told me that Mighty Samson at Gold Key was sort of a signal event for you.

THORNE: Samson was the first comic-book series that I designed all the characters and costumes. It was very exciting because I was working with Otto Binder, and no, I never met him either. I often wonder what happened to those original Samson pages. In those days they didn’t return the artwork. I did seven issues of old smelly Sam.

GROTH: Right. And Jack Sparling took it over after you left.

THORNE: Jack was a good craftsman, but he raced through Samson like Mike Schumacher at the Indy 500. [Laughs.] In the ’40s Jack drew Hap Hopper for United Features, and then there was his Claire Voyant. Samson didn’t last long after Jack’s speedy ministrations. Sam was very well written, and my style was coalescing. It could have been my vision of Samson’s post-apocalyptic world that caught the eye of the Marvel people when they were considering an artist for Sonja. Incidentally, I have in hand a request for payment form dated October 14, 1965, it’s for 12 penciled pages of “Sinister Satellites,” a Samson story, at $17.50 a “unit” or page, that’s $210.00. The pay was the same for the inked pages. That adds up to 35 bucks a page; which included lettering and coloring.

GROTH: Peonage by today’s standards.

THORNE: By the way, I loved drawing the softly beautiful Sharmaine, Sam’s girlfriend.

GROTH: Samson was the most extensive narrative you had done up to that point, I think.

THORNE: Yeah, and it made drawing comic books all the more seductive.

GROTH: Right. So you got the whole Samson script and just illustrated it.

THORNE: They were full scripts with dialogue and scene description on typed pages. I had license to work it up from there.

GROTH: The covers of the Samson books were painted, which was unusual for comic books.

THORNE: A painter I’m not. I was born a watercolorist, although I’ve done a lot of commercial illustrations with acrylics and tempera. My Playboy stuff is done with Dr. Martin’s TECH waterproof dyes. I apply them using a watercolor technique, which gives the gags a spontaneity and freshness that you can’t achieve with opaque colors.

GROTH: I chanced upon some of your work for the Boris Karloff horror books.

THORNE: I did a few Karloffs and some Twilight Zone stories.

GROTH: You were in good company — you shared the comics with great artists like Al Williamson and Wally Wood, though not quite at their best.

THORNE: Fred Fredericks also segued from Dell to Gold Key. At Dell he was writing books like Nancy and Sluggo and Heckle and Jeckle; it was really funny stuff. When he went over to Gold Key, he started writing and drawing the books. Among them The Munsters, Mister Ed and other titles; they were hilarious.

GROTH: He’s a good gag writer, right?

THORNE: Fred’s written some of my Playboy gags. Not Moonshine McJugs — I wrote and drew all the Moon material. Fred’s been doing Mandrake the Magician for over 40 years, and he’s bored out of his skull. He’s been writing the stories in the past few years, and they’re well done, but it’s straight adventure material. Fred’s an enormous talent, but because of Manny, we missed out on his humor writing.

GROTH: Toth was at Dell and Gold Key at that time.

THORNE: He was doing wonderful things, movie adaptations, Zorro and other titles. Toth owned the ’50s and ’60s. He influenced a lot of Young Lions of that era.

GARY: Did you meet him?

THORNE: I didn’t meet Wally, Fred or Toth until years later. I did meet Tom Gill. He was the anointed Lone Ranger artist. When you did a Lone Ranger, you couldn’t draw his head. Tom would come in and finish the head! [Laughs.] Jesse Marsh was on board as well. He had his own distinctive style; it was different and as solid as a brick church. His John Carter of Mars and Tarzan were fabulous.

GROTH: Yeah, Marsh is underrated — or not rated. Now, why didn’t you continue Mighty Samson?

THORNE: I was happily burdened with a lot of commercial illustration, and it was much more lucrative. We had four kids by that time and we needed the moolah. I was doing regular illustrations for the Golden Books and the Golden Magazine. I worked with Ed Marine, the editor who helped me develop my color illustrative style. Then there was David C. Cook, the publisher of religious books and magazines. Yes, Gary, I did more drawings of little kids praying than tits in those days! [Laughs.] But best of all were the Bell Telephone Company assignments. The pay was fabulous, not as good as Playboy these days, but it sure brought home the old bacon. I did a lot of illustrations for the Tel-News insert that arrived with the bill each month in the subscriber’s mailbox. They were big juicy illustrations of historical subjects. And it paid over 800 bucks a pop.

GROTH: That’s like 10 times the amount what you’d make doing the equivalent work for comics.

THORNE: Absolutely. And I could knock one of those babies out in three or four days. One assignment I did for the Bell Tel-News was to illustrate the Clamtown Sail Car. In the late 1800s some innovative clammers in Tuckerton N.J. built a narrow gauge rail line from Barnegat Bay to the center of the village. When the wind was right the sail car would deliver the morning’s clam harvest to waiting customers in Tuckerton. There was no record of what the sail car looked like, so it was up to me to get down to Tuckerton and interview a 90-year-old coot who could recall its appearance. The town historian took me to the old guy’s house and it turns out that he’s blind as a shovel-nosed fruit bat, and he has a grudge against the phone company! He refused to talk to me. He shut up like a clam! [Laughs.] After about 20 minutes, the town historian, an elderly lady, finally cajoled the old geezer into describing the sail car. The finished painting of The Clamtown Sail Car now hangs in the Tuckerton Seaport Museum.

GROTH: The pay for illustration was good, but page rates for comic books were rising slowly, weren’t they?

THORNE: Very slowly.

GROTH: Now, you inked all your own comic-book work, didn’t you?

THORNE: Yes.

GROTH: That seems to be a little unusual. Certainly at Marvel and DC, where they usually had inkers over the artists so that the penciler could crank out more pages and increase productivity since the inker could be less proficient than the penciler. The penciler may not have particularly like the inker that was assigned him, but he had to accept it.

THORNE: I think Joe Kubert is the only one that ever inked my pencils. It was a six-page Tarzan story. He did a great job. I was honored. He’s a genius, and I’m in love with his wife! [Laughs.]

GROTH: We know that! Now, did you letter your own stuff, as well?

THORNE: Oh yeah, and I colored the stuff, too.

GROTH: So you did everything, really.

THORNE: Normally, it’s like a cottage industry. I always felt more respect for the guys that did it all themselves, including the writing. I’m really dumb on comics, and it’s embarrassing. I haven’t been to a stateside con in 29 years. Recently I was invited to a one-day Fantasy Expo at the Du Cret School of the Arts, little private art school in nearby Plainfield. They had a good crowd, but you know, they’re asking me questions about comics and I’m like duh? [Laughs.] I was presented with an honorary diploma! I’m standing there like a badly aging lion thinking, I owe so much to the fan base, and I should be more attentive to the annals of the craft. I don’t read them or collect them, but comic books have given me an enviable lifestyle. I always say I can’t retire because I never had a job! [Laughs.]

NO LONGER STAID

GROTH: After Gold Key came DC.

THORNE: During the DC years, my commercial illustration withered somewhat, so I was happy to have Tomahawk, Hawk, Korak and the war books. I loved working with the writer and editor Archie Goodwin. He was a truly splendid human being, and he drew very well. Kanigher wrote a lot of the stories that I drew, but I can’t recall meeting him. I do remember meeting Murray Boltinoff. I wasn’t in the DC offices all that often. When Carmine Infantino took the top job at DC he requested that all the guys working on the books come to his office for a big meeting. He wanted to pump us up with his vision of DC’s future under his command. Can you imagine talking seriously to a bunch of fractious cartoonists? Worse yet, Infantino was a cartoonist, one of us, so the meeting quickly degenerated into pandemonium. One guy pulled his pants down so he could rub his bare ass on Carmine’s velour couch! [Laughs.]

GROTH: Carmine didn’t last too long at the helm, but he was a damn good draftsman.

THORNE: I occasionally saw Joe Kubert, who edited some of my war stuff. I’m in love with Muriel, his beautiful wife. She has a fantastic business sense. Incidentally, hung on the wall behind the Kuberts’ bed is a collection of original oil paintings of pulp-magazine covers. Fabulous. To eliminate any hint of impropriety; let the record read that I was not bedding Muriel when I saw the collection! It was at a social evening.

GROTH: The record stands as read. I assume DC paid better than Gold Key.

THORNE: It was better pay, but not much.

GROTH: Do you remember who you initially spoke to at DC?

THORNE: Could have been Archie. I did a couple of Civil War stories with him. It was the best working with Archie. So they kept giving me a lot of the war stories because they thought I had a Joe Kubert style. Although I greatly admired Joe’s work, I was never consciously influenced by him.

GROTH: They gave you Enemy Ace.

THORNE: I ask you, how could anybody do the immortal Enemy Ace in anything but the Kubert style? Nobody could touch Joe with the war stuff. His style is so loose and gritty. You can smell Sgt. Rock. Joe’s the Matt Clark of comics. Joe’s stuff always looks right, even if it goes beyond the boundaries of logic.

GROTH: Joe was your editor at DC.

THORNE: One of several, and one of the best.

GROTH: And they were written by a variety of people.

THORNE: A lot were by Bob Kanigher, he was the workhorse at DC. He was very prolific, a natural storyteller.

GROTH: Some were written by Mike Friedrich and Bob Haney. Did you ever talk to the writers over the phone?

THORNE: No. It’s a very insular craft. Paul S. Newman called me once when I was freelancing at Gold Key, and I had a delightful phone conversation with Clair Noto. That’s about it. Of course I knew Wendy Pini, and it was a pleasure.

GROTH: The closest you came to doing a superhero was The Spectre for DC.

THORNE: Yeah. Was he a superhero? I can’t recall; did he wear a cape and tights? I did one, maybe two stories.

GROTH: That’s right, and one of them became notorious.

THORNE: The one about the mannequins.

GROTH: Tell me about it.

THORNE: It was a story published with the Comics Code’s Seal of Approval. In brief, through sorcery, an evildoer animates a bunch of department-store mannequins. They go on a rampage of killing customers with meat cleavers — I mean we’re talking bloody decapitation and severing arms. But, folks, they still were mannequins. The old curmudgeon C.C. Beck, of Captain Marvel fame, sees the story. I’d guess he didn’t read it. Had he, perhaps he wouldn’t have drawn attention to it by blasting it in a fanzine as horrendous, and an example of how despicable some of the books had become. It was a cause célèbre at the time. In short, the shit hit the fan.

GROTH: You know that The Spectre that you illustrated was written by Michael Fleisher, right?

THORNE: Oh.