Roz Chast was born in 1954 and grew up in Kensington, Brooklyn (then a part of Flatbush). Her parents, with whom she would have a lifelong troubled relationship, both worked in the local school system: George Chast was a French and Spanish teacher at Lafayette High School and Elizabeth Chast was an assistant principal at various public schools. They were smart, educated, intellectually arid, and undemonstrative. George was a sweet-natured man, loving in his way, but his temperament was subservient to his wife’s objurgatory personality, and so his affection was muted. Chast’s own description of her mother, from interviews and her memoir Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant?, reminded me of Deirdre Bair’s colorful description of Saul Steinberg’s mother Rosa in her magisterial biography: She “gave the appearance of a dreadnought in full sail as she slashed and battled her way to primacy in all things connected with her family.” Chast has had little good to say about the neighborhood she grew up in or the adversarial family life in which she was raised. “Brooklyn, to me” she told the Washington Post, “symbolized hopelessness, claustrophobia, fear, loneliness, frustration, and a lot of rage. I didn’t have friends, I hated high school…and my parents were not terrible people, but we didn’t have much to talk about. It was very grim.” As if that weren’t enough, she adds, “I even hated my room, with its hideous furniture from my uncle’s furniture store and disgusting curtains and buckled white and gold dirty linoleum — all of which my mother had chosen and shoved into my tiny bedroom at various times in my childhood.” She was, of course, an only child. (Her mother lost her younger sister at birth, an event the family was never allowed to talk about.)

Roz Chast was born in 1954 and grew up in Kensington, Brooklyn (then a part of Flatbush). Her parents, with whom she would have a lifelong troubled relationship, both worked in the local school system: George Chast was a French and Spanish teacher at Lafayette High School and Elizabeth Chast was an assistant principal at various public schools. They were smart, educated, intellectually arid, and undemonstrative. George was a sweet-natured man, loving in his way, but his temperament was subservient to his wife’s objurgatory personality, and so his affection was muted. Chast’s own description of her mother, from interviews and her memoir Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant?, reminded me of Deirdre Bair’s colorful description of Saul Steinberg’s mother Rosa in her magisterial biography: She “gave the appearance of a dreadnought in full sail as she slashed and battled her way to primacy in all things connected with her family.” Chast has had little good to say about the neighborhood she grew up in or the adversarial family life in which she was raised. “Brooklyn, to me” she told the Washington Post, “symbolized hopelessness, claustrophobia, fear, loneliness, frustration, and a lot of rage. I didn’t have friends, I hated high school…and my parents were not terrible people, but we didn’t have much to talk about. It was very grim.” As if that weren’t enough, she adds, “I even hated my room, with its hideous furniture from my uncle’s furniture store and disgusting curtains and buckled white and gold dirty linoleum — all of which my mother had chosen and shoved into my tiny bedroom at various times in my childhood.” She was, of course, an only child. (Her mother lost her younger sister at birth, an event the family was never allowed to talk about.)

Highlights of her academic career through high school include skipping a year in middle school under the New York Special Progress Program and winning the Kiwanis Club Award for best poster for the topic “Honor America,” one of the finest ironies ever recorded in the biography of a cartoonist. Her social life was either fraught or nonexistent. “My mother had this idea that if I ever socialized with other kids at the very best I would come home with impetigo and at worst I would be learning things I shouldn’t be learning. So my childhood was about avoiding other children. It was like being locked in a Skinner box.” She described herself, then, as “shy, hostile, and paranoid.”

(In other words, the curriculum vitae of damned near every great artist of her generation — or, maybe, of every generation.)

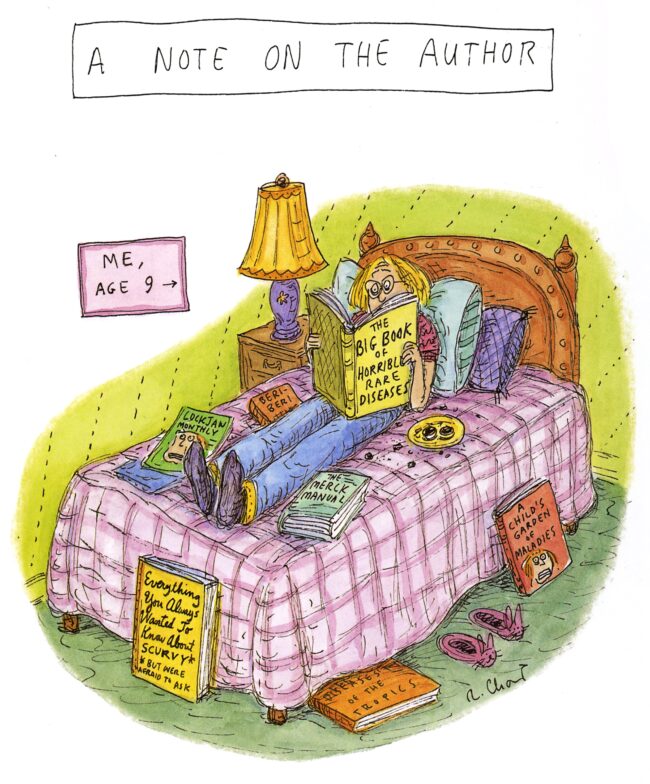

All the while, she was, in her social isolation and familial anomie, looking at comics and cartooning and drawing her own from as early as she can remember. The earliest comic she can remember reading was Archie. She discovered Charles Addams in the library of Cornell University on one of the family’s annual pilgrimages to upstate New York where they would detour to Cornell to attend lectures “for, as my mother put it, ‘a certain degree of intellectualism.’” Stuck happily in the library, she also fond cartoon collections by Peter Arno, Helen Hokinson, George Price, and Otto Soglow, but it was Addams who bent her brain. By the time she was 12 she was reading Mad magazine, and was especially taken by Don Martin. Later, Saul Steinberg and William Steig would become heroes (about Steig, she wrote, “Steig gave himself permission to be playful and experimental, and to follow his artistic heart, wherever it led,” which sounds like a description of herself.) Edward Gorey and Jules Feiffer would follow. (She was never seduced by underground comics; even though they reflected the kind of artistic freedom she would demand throughout her career, they were in the main too aggressively male and calculatedly scatological for her tastes.)

In 1970, she, mercifully, left home and entered Kirkland College in Clinton, New York, where she studied lithography, screen printing, silk-screening, etching, and printing. From there she transferred to the highly regarded and academically more strenuous Rhode Island School of Art and Design (which, incidentally, boasts a number of notable cartoonists among its alumni, including Walt Simonson and David Mazzucchelli). She first studied design under Malcolm Grear, known for his clean, minimalist, industrial aesthetic, which she quickly learned was anathema to her own. She quickly moved over to illustration, then to painting. She continued to draw cartoons for herself. “One of the more terrible things about cartooning,” she said, “is that you’re trying to make people laugh, and that was very bad in art school during the mid-’70s. This was the height of Donald Judd’s minimalism, or Vito Acconci’s and Chris Burden’s performance art. The quintessential work of that time would be a monitor with static on it being watched by another video monitor, which would then get static.” At RISD she learned that she was not going to be a ductile careerist, going with the trendy flow of whatever was “in” at the moment, but adhere to her own point of view, wherever that led her.

Nonetheless, she managed to graduate from RISD in 1977, and moved back to New York and embarked upon what was then considered the essential cartoonist’s baptism of fire — pounding the pavement, looking for freelance work from magazines, the grueling task of selling oneself in a ruthless commercial landscape. Her first break came when, in a cross between a leap of faith and an act of desperation, she approached Christopher Street, an upscale gay literary magazine, which started published her work — $10 a cartoon, which was niggardly even in the mid 1970s but wholly welcome by the struggling 23-year-old artist. She started appearing in the Village Voice and occasionally got assignments from Ms magazine. In 1978, she once again went for a long shot by trying her luck with the New Yorker by dropping off an envelope with 60 gag cartoons on their submissions day. Why a long shot? Neither her drawing nor her sensibility resembled the typical New Yorker cartoonist. And she was a woman. In what can now be seen, in retrospect, as typical Chastian determination, what many an artist would have seen as insurmountable obstacles didn’t faze her in the least — if she even noticed them. And regardless of (or perhaps because of) these attributes, the New Yorker’s cartoon editor, Lee Lorenz, a particularly incisive critical intellect, immediately bought a cartoon and made her a regular contributor. Here’s how he remembers it: “The first time Roz Chast came in, I showed her stuff to [William] Shawn and said, ‘I think we should go for a contract right away…’ He agreed but said, ‘Do you think she can keep it up?’ Well, she did keep it up. But there was such an uproar when she started appearing in the magazine. When I tell people, they think I’m making this all up, but no! The artists didn’t like her work and said she couldn’t draw. There were still all these craftsmen contributing to the magazine, and that was the model of New Yorker cartoons. But hers weren’t funny in the same way and they weren’t drawn in the same way. It was a radical departure.”

Chast represented a radical departure in two different ways.

First, her drawing technique was pretty much in direct opposition to the New Yorker’s traditional cartooning aesthetic. Visually, New Yorker cartoonists were known for their masterful draftsmanship and their elegant line. The posture was often (but not always) one of disdainful, distant bemusement at the folly of the bourgeoisie of which they were clearly a member in good standing, and wouldn’t have it any other way. There were exceptions, of course, but even an artist like George Booth, whose kitchen sink drawings and mangy mongrels, rendered in a hilariously grungy, dilapidated line, were in their own ways virtuosic. Chast’s drawings reflected the integrity of her sensibility over technique.

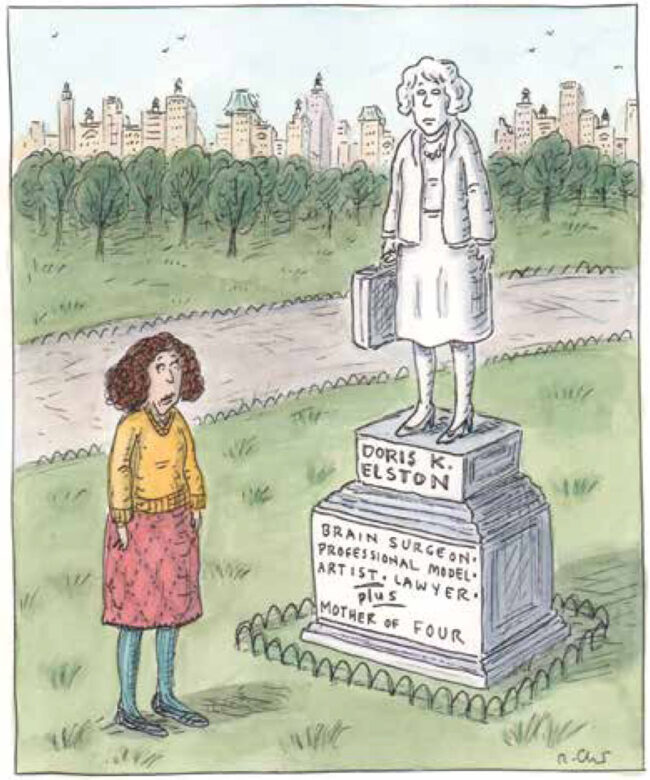

Second, not to belabor the obvious, she was a woman. At the time she began contributing to the New Yorker (1978), there was exactly one other woman cartoonist appearing in the magazine — Nurit Karlin. Prior to Chast’s arrival, and to Karlin, whose work began appearing in the New Yorker in 1974, the magazine published exactly three other women cartoonists on a regular basis: Barbara Shermund, Mary Petty, and Helen Hokinson (the latter two of whom were major inspirations to Chast). Liza Donnelly sold her first cartoon to the magazine a year later, in 1979, and became a regular contributor in 1982. The cartooning profession has been dominated by men since its inception, something closer to gender parity being achieved only in the last decade. But when Chast was making the rounds and trying to sell cartoons in the late ‘70s, I’m willing to bet that women cartoonists comprised less than 5% of working professionals. This didn’t intimidate Chast one bit. She was hell-bent on becoming a professional cartoonist; and she not only succeeded, but succeeded in becoming one of the most prominent cartoonists at the preeminent magazine known for its cartoons.

Chast has appeared in virtually every issue of the New Yorker from then until now, indeed, has become one of the most recognizable and popular cartoonists in the magazine. Her contributions vary widely, from full-page (and even occasionally two-page) panel-to-panel continuities to the more traditional gag cartoon, and within the gag cartoon form she’ll create fake magazine covers (a favorite device), fake board games, multiple non-narrative panels illustrating variations of a theme. She’s also big on lists and diagrams. She did one diagrammatic page, “Welcome to the Universe in a Grain of Sand,” that, in its insanely interconnected complicatedness, lives up its title. “The New Yorker,” she once said, “has let me explore different formats, whether it’s a page or a single panel, and that’s very important to me. If I had to do a newspaper strip where it’s boom, boom, punch line, I would kill myself. I’m amazed people can do this without feeling like they’ve just gone to sleep.”

Chast’s bête noire is the affluent society: mass marketing and its victims and beneficiaries, about which she devotes a significant percentage of her cartooning energy. Her targets can be the merely cretinous (witless slogans on clothing that consumers lap up) to the downright evil (tobacco company propaganda), but they are all done with her trademark absurdity, as if she herself can’t believe the reality she is satirizing. She depicts consumers as saps, dupes, and collaborators, slaves of commercial culture. Haplessness is the sorry state of most of her characters, which she draws, regardless of age or gender, as an Everyschlub: both genders share the same, amorphous, pear-shaped body — the men are bosthoonish, balding with tufts of hair on either side of their heads; the women look like they were modeled after Shirley Booth, all looking slightly dumbstruck. These are people you would avoid if you saw them at a party, though it’s unlikely they would be found at one (and especially not one of Charles Saxon’s). They are usually victims — of their own incuriosity, their shallowness, their passivity, their fears — and therefore easy prey. It is not a pretty picture, collectively speaking, and if they weren’t as funny as they are, they would be too despairing to look at.

Not all of her cartoons are this coruscating, of course. Some of them are gentler jibes at the absurdities and anomalies of contemporary life. Interestingly, very few are distinctly political or ideological; I found fewer than a dozen cartoons that target political issues or individuals. Her beat is culture, not politics. She works in a variety of registers within the Chastian sensibility and one of the most aesthetically delightful is the piquant observation that combines her off-kilter point of view with an ingenious imagination and ironic wordplay (“The Velcros at Home” depicts a nuclear family and their pets and furniture velcroed to the wall; “Loss Leaders” depicts her typical Everyschlubs standing and staring out into space). Some are simply ineffably weird and inexplicably potent, probably because they tap deeply into something impalpable but recognizable.

True to her word, she has never drawn a comic strip, but, like many cartoonists who have appeared in the New Yorker — Gahan Wilson, Saul Steinberg, James Thurber, Liana Finck, Jules Feiffer, Otto Soglow, so many others — Chast does a vast variety of work outside the purview of that magazine. She is incredibly prolific.

Her masterpiece, as far as I’m concerned, is her 2014 memoir, Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant?. It is to Chast what Nuts was to Gahan Wilson, the most substantial, single, unified work she has accomplished to date. It is as if everything she had done before this was leading up to it and that she had finally found a subject worthy of all the skills she had learned up to this point.

It is not only the story of her parents’ slow death, but, equally if not more importantly, of their relationship to each other and her relationship to them. Although she suppressed, somewhat, her goofier visual stylizations, her humor remains very much intact and is in fact an integral part of the work. If I can borrow from Lubitsch, there’s the Chast Touch in the imagery, which strikes a perfect equipoise between caricature and tragedy, creating three-dimensional characters as seen through the prism of memory. This balance — exaggerated cartooning one minute, subdued stillness (or what passes for “realism” in the Chast world) the next — is a remarkable feat. Her humor, usually self-deprecating and self-reproaching, but also often aimed at her parents’ exasperatingly grating tics and painful obtuseness, actually deepens the profound lifelong emotional dissonance between daughter and parents.

I am pleased to report that Roz Chast the person is just as funny and witty and ironic as you would expect her to be from her work (which is not always the case). This interview was conducted in two sessions on January 11 and 12, 2020, and combined. I would like to thank Ms. Chast for her perseverance and patience, which went far above and beyond the call of duty, in suffering the process of this interview, which was uncharacteristically difficult (she knows what I mean). It was a great pleasure interviewing her. -Gary Groth

Were you intimidated by how male-dominated the cartooning profession was in the ’70s?

I think I wasn’t intimidated by that. No.

Did you even think about it?

I didn’t really think about it that much. I mean, I thought about it a little bit with the underground stuff.

Because that was more aggressively male perhaps?

I think it was more aggressively male. And the New Yorker was very male. I just didn’t think that much about it. That, I think, has something to do … Even though I have many, many bones to pick with my mother and probably will until the day I die, I think I can credit her with growing up thinking of myself first as a person. And being a woman was just a variety of person. Just another attribute of being a person. I didn’t even think about it that much until I got older and realized, “Oh, all of the language reflects [gender].” Like “Mankind,” and women are some sort of strange other. I just didn’t think of myself like that. I thought of myself as a person. And I thought of my work as work done by a person, not work done by a woman. It’s funny because I was just going through some of my childhood drawings and I signed them when as I was a kid as R. Chast. I don’t know why, but all of them are signed with my initials. I wasn’t trying to hide that I was female, it was just that that’s how it seemed that artists signed their work. With their initials. Or with their last names.

So if you didn’t think you were being oppressed by the patriarchy, were you not being oppressed by the patriarchy?

I don’t know. I mean, I think I probably was, but on the other hand, I think that it was probably in my favor. I know when I submitted myself to The New Yorker, I submitted it with the initials. So when they pulled me out of the slush pile — you know, when you drop off your portfolio and come back to pick it up — Lee Lorenz didn’t know if I was male of female or anything about me. But when he asked to meet me, I think it probably was good that I was female because at that point their staff was all male. Except for Nurit Karlin, who only came in occasionally.

She was literarily the only other woman cartoonist at The New Yorker at that time.

Yeah.

Why do you think it was good that you were a woman?

Oh, I think that it was just starting to occur to them in 1978 that maybe it was a little bit too much of a boy’s club. And that maybe it would be interesting to have a female voice in there. I think that when he met me, it was like, “Oh, I like this person’s work. And they happen to be female. And they happen to be under 35.”

I was going to say under 60.

Yeah, under 60. The next youngest person was, I think, Bob Mankoff who was 10 years older than me. I was 23. I think I probably checked a couple of boxes.

Did you think that signing your name with your initials was a way of hiding your gender?

I had always done it since I was a kid. It’s funny because — it hasn’t happened too many times, but a couple of times I’ve read, “She signs her work R. Chast as an homage to R. Crumb.” And it’s like, “No. Fuck you!” No, no, no. I can prove it to you. I can show you drawings I did when I was 10, 11, 12 years old. I signed them with my initials.” I think because that’s how I saw artists sign their name. Either their last name or their initials.

Did your upbringing in this regard help you navigate the male-dominated corporate world at the New Yorker and elsewhere?

If I wanted to be taken seriously as a person, to go into an office and play female games, to get ahead using any kind of batting of the eyelashes was very much a losing — this was something that was going to backfire and blow up in your face.

And you understood this?

Oh, I understood it completely. It was like I’m never going to pretend to be one of the boys. I’m never going to play that game. I think that that’s a kind of strength that she passed onto me. I’m never going to pretend that if you say something awful that I can take a joke like I’m one of the boys. I’m not going to play that game. I’m a woman second and a person first. So that’s probably a good thing.

I’m not sure how to put this, but…I think that’s not the case today.

Yeah, I know. I know. I know. It’s gotten very … I don’t know.

I think in our current moment you’re your gender first and a person about 10th or 11th down the line. Do you feel a little out of time?

I’ve never felt ever that I really fit in completely at any stage. I always felt a little bit weird. [Laughter.]

Really [facetiously]?

Yeah, I know that comes as a shock. [Laughs.] I think that’s probably the cartoonist’s life. It’s why we spend most of our time by ourselves locked in a room with our projects.

Hunched over a board.

Hunched over a board fussing over some odd piece of embroidery or rug or egg or whatever the hell you’re working on.

There are very few cartoonists that could reference an egg in that context. You’re one of them.

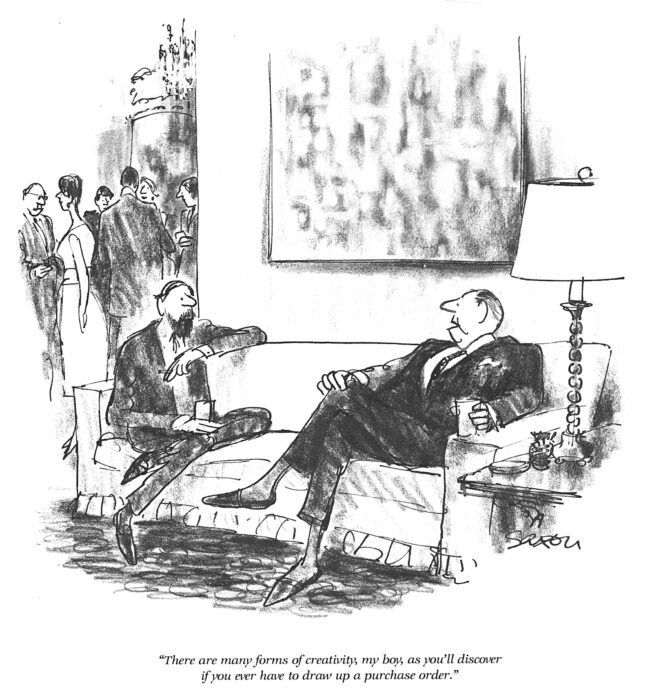

Getting back to gender and The New Yorker — I think I referred to it, but I don’t think you actually talked about the first New Yorker party you went to, where you had this exchange with Charles Saxon; quoting you, you said, “At my first New Yorker party, Charles Saxon came up to me and had things to say about my drawing style. He even asked me, ‘Why do you draw the way you do?’” [Laughs.] Now, did he say that in a kind of high-handed aristocratic way?

Yes, yes. It was not like somebody actually asking me that. It was accusatory, and his subsequent comments confirmed that. He said that my drawings looked unfinished, and I still remember, he said, “Which artists do you admire?” And I think at the time I was going through this huge Raoul Dufy phase, and his comment was so bizarre. I think even at the time I knew it was weird. I said, “Well, I really like Raoul Dufy.” And he said, “Dufy had a lot more power in his line than you do.” [Laughter.] I was like, “OK. I guess you’re right.” What am I supposed to say?

So the conversation was basically him expressing skepticism at your drawing and your inclusion in The New Yorker.

If not hostility. [Laughs.] I would say there was definitely hostility as well. Like I was some sort of pretender or schemer or something.

An intruder.

An intruder more than anything else.

So it was not friendly?

It was not friendly.

That must’ve rocked you back on your heels a little.

It was awful. I mean, I sort of cried a little. Not right in front of him, my God, but I went — I don’t remember, I went to the ladies’ room or something. It was just awful. Especially because he was a hero of mine. I loved his work and I still do. But something about what I did just really — I don’t know whether he thought I was lazy, or an interloper, or terrible, or I had ruined a private club of his or something, you know?

How do you think your gender played into how welcomed you were at The New Yorker? Did that play any part in it, do you think?

I can’t crawl inside these peoples’ heads. I mean, they may have had trouble with it, you know. A female artist, especially a very young one, and especially one whose drawing was completely different from theirs. How I had a very different sense of humor and a sense of drawing. I think that being female was only a part of it.

Did you ever feel that some of the hostility was specifically because you were a woman?

No, not in any direct way. I think because they had so many other problems with me that being female was minor [Laughter.].

That was low on the list.

That was low on the list. I think if I had been female and drawn in their way, it would’ve been much more acceptable.

I’m not sure if I’ve done an exhaustive survey, but I couldn’t find more than four women cartoonists who worked in the magazine before you arrived.

Mary Petty. Barbara Shermund. Helen Hokinson. Nurit Karlin.

And that’s all I could find.

Those are the only ones I know of. That’s sad.

I’d be willing to say maybe there were one or two more, but that’s a pretty piss poor record. Did you ever ask Lee or talk to anybody else there, and ask, why aren’t there women cartoonists who work here?

I think because I just never thought about gender that much. Maybe that’s why in some ways I’m very blockheaded. I just really thought about jokes, and work, and drawing. It just was not something I thought about all that much.

Have you given it any thought since?

I have thought about it some.

Do you have a theory?

I think that for a lot of women, being funny — it’s very hard. I mean I know women who do it. There’s comediennes who are funny and also seductive. But, Greta Garbo isn’t there making jokes. Seduction is a pretty serious business. Making jokes, finding things funny, finding situations absurd — men are allowed to do that. But I don’t know, maybe it’s more complicated for women. I don’t know, I don’t know. Now I’m just blabbering.

It seems to me it has to be one of two things, which is that either women didn’t submit cartoons. Or women submitted them and they were rejected for sexist reasons. And of course, I don’t think any of us knows the answer to that.

No, I don’t think so either. I think about it like this. The National Lampoon, they have that great book Titters. You remember?

Yeah, yeah.

And there were women cartoonists, but not a ton. I mean, Mad magazine was very male. The National Lampoon, as you pointed out, was very male.

The Lampoon actually had a greater proportion of women cartoonists.

Yeah, they did. Things were starting to change a little bit.

But is that because there were more women cartoonists in general? I mean, cartooning had always been a very male dominated —

It has, but much less so now. You know, I did the Best American Comics thing in 2016. And you know Bill Kartalopoulos, of course. I think he winnowed it down to 130 different pieces, from which I chose about 30. And it wound up being — without any effort on my part to make it be even — it wound up being almost 50/50 men and women. I love that there are so many incredibly great graphic novels — a lot of them are memoirs, but they’re all called novels— graphic “novels” that are by women. That is just the greatest thing to me.

I’d say that there are more women cartoonists proportionally now than ever before. But not only that, I think what’s even more important is that there are more great women cartoonists.

Yeah! Absolutely, absolutely. I mean, you think of Gabrielle Bell, and I’m looking at a book about the comics of Julie Doucet. Liana Finck. There are tons of people in The New Yorker. Julia Wertz, who I mentioned before. Lauren Weinstein. There’s a lot of people I follow on Instagram whose work is just extraordinary.

Emil Ferris.

Oh my God, Emil Ferris! Nora Krug, who wrote Belonging. There’s just really, really good stuff, and it just seems more open. It’s very exciting, and again, it’s not grown-up money. And the internet aspect, where people are like, “Why don’t you do this piece and it will give you exposure. We’ll pay you 50 dollars but you’ll have exposure!” That’s terrible.

You and I remember the time when there were like six women cartoonists.

Yeah!

I remember the time when I would walk into a party at a convention, and there literally would be six women in there, and three of them were girlfriends dragged in by their boyfriends.

Yes, yes. I mean, you’ve seen Very Semi-Serious, that movie that’s made about The New Yorker cartoonists. And it’s almost all guys. But a couple of years ago I was at SPX. I think more than half of the people were female, and there were so many young people, a lot of trans people, there are definitely gay people, lesbians, trans, women, many more people of color. Much more diverse. If only there were more money flowing around. That would make it fantastic. But it’s much better. Just what we were talking about yesterday, the underground comic scene with guys in blue jeans that haven’t been washed in a month, talking about using that word that I don’t even want to say out loud because I hate it so much — chicks. Just that grossness. Not just grossness of dirtiness, but grossness of assumption, like they’re the only ones in the world that have stories to tell. And this is better.

You’re right that the common denominator today isn’t male, it’s economic impoverishment.

Yeah, impoverishment. It sucks. It’s terrible. And this is off the topic, but I have a kid who is working as a counselor, as a therapist, and all the money seems to be like — Jeff Bezos and Mark Zuckerberg seem to have all the money and everybody else just gets what falls between the sofa cushions.

But this has to be true of novelists and filmmakers and every other discipline too.

Yeah, everybody! It’s weird. It’s not just cartoonists. We’re just trying to figure out how to make a living. Whether it’s possible to make a living doing what you love to do, and doing what is important. For me, looking at graphic novels and reading books — it keeps me further away from the edge of the cliff, along with working. Not just me, but I’m sure that other people who love to read, and love graphic novels, and who love comics and love cartoons — it’s not just fitting in around the edge — this is a daily, extremely important part of our lives. As I’m sure you know, because you’re Gary Groth.

THE VALUE OF DRAUGHTSMANSHIP

You’ve drawn a variety of other things outside of The New Yorker, and your graphic memoir, and your New York book, which we haven’t even talked about. You drew 21 covers for a series of classical CDs.

Yeah, that was fun.

How did that come about? Are you a classical music fan?

I like classical music. I like all sorts of music. Deutsche Gramophone came to me and said that we’re doing these series called “Mad About,” and would you be interested? And the money was good, and the job was fun, and it was wonderful. It was a very, very fun job. They had Mad About Puccini. I do like opera. Not all opera. I like the classics. I like La Boheme, and I like Carmen. I like Puccini, I like Verdi. It was just a lot of fun, and there were tons. There were Mad About the Piano, Mad About Music from Films, Mad About Music from Cartoons. It was very fun. And color. And they had a sense of humor. They were all cartoons. If I was drawing Carmen, she would be my version of Carmen. They didn’t expect me or ask me to draw in some weird style. That would not have worked out.

You’ve done a few children’s books.

Children’s books, and I’ve illustrated books for people, and I did a book with Stephin Merritt and Calvin Trillin and Dan Menaker.

You’ve written and drawn children’s books by yourself but you’ve also collaborated with Steve Martin, who also interviewed you.

Yeah! He’s amazing.

How did the book with Steve Martin come about?

How did the book with Steve Martin come about?

He asked me if I wanted to do it. I knew him a little bit through The New Yorker connection, I met him. Again, it was a very fun project.

How is he to work with?

He was great. He’s such a great guy. Very smart, very self-effacing. He’s very aware that he is a mega superstar, and walking down the street with him is just wild.

Because he’s stopped every ten feet or something?

Oh, everybody recognizes him. He’s very recognizable. It must be a burden in some ways for him, but it’s quite amazing. And he’s a good person to work with, and we had fun. Thinking up words. And he has written most of the verses, but sometimes we would get together and try to think up other words that started with the letter U that were funny that we hadn’t thought about. Uvula or ukulele, you know? And that’s a whole other thing that I’ve gotten involved in with Patty Marx. Collaboration is fun.

So you enjoy collaborating?

I love it. If I’m collaborating with the right person, it’s super fun. Then you have the chance to make each other laugh, you know?

Most of your comics are done entirely by yourself. Do you consider yourself as much a writer as an artist?

[Long pause.] Yeah, I think it’s probably 50/50.

That’s what I would say. First of all, some of your work has huge blocks of writing.

Yes, definitely.

Second of all, I think you write with your drawings.

I think it’s about a 50/50 thing. I’ve seen cartoonists like Chris Ware who are so visual. Or Nick Drnaso. There are pages of pictures and no words. I don’t think that’s me.

Had you ever considered becoming strictly a prose writer?

No, no, because I think that I would miss the drawing.

And there’d be something missing in you.

Yeah, yeah. I feel like the drawings are still so important in telling whatever story I’m telling. And the thing that is so great about cartooning is that cartoons are not an illustration of what you’ve written. I think of it like there’s the treble clef and the bass clef. The two play together but they can be the same thing or totally different. You can have, “That was the happiest day of my life,” and then the drawing is something totally different, you know?

Yes. And that creates an entirely different meaning.

An entirely different meaning and a totally different way of telling the story too. With a cartoon you have this ability to tell two stories. You’re telling the same story, but telling them in different ways. There’s this vibration between — we’re getting so high falootin’ here— between the pictures and the words.

And that’s true of a single panel gag cartoon as a well as sequential panels, isn’t it?

Absolutely, absolutely. Think about any cartoonist who has their own voice. Visual voice. Like George Booth or Ed Koren. Helen Hokinson. I know I’m only mentioning the oldies. Charles Addams, of course. It’s not just a generic cartoon drawing. It’s a very specific sort of vibe that goes along with the words. I love that.

So, this is going to be for better or worse, very organic.

I only eat organic things. You know me. My body is a temple!

It’s appropriate that you’d give an organic interview then.

Yes, yes. And the phone I’m talking on is organic. [Laughter.] It’s farm to table. Or farm to ear.

You said you were very influenced by, or at least inspired by Hokinson and Mary Petty.

Mainly Mary Petty. She’s odd. Helen Hokinson, I love her stuff very, very much and I love that she has a world that she draws. It’s not just generic. It’s very much her world and I love that. The club ladies. My mother used to say about the Hokinson ladies, “She had a bosom like the prow of a ship. Then their feet were these teeny, tiny little things and they would always wear these hats. I love her stuff, but Mary Petty was self-taught and drawing style is a lot quirkier, I think. I just love it so much. I love that it’s not always smooth, in a certain way. It’s just — I don’t know. I just love it.

Hokinson’s draughtsmanship is probably more impeccable than Petty’s, but what struck me was how different they were from you. Even Petty had this kind of delicacy to her line, which you eschew. I noticed among New Yorker cartoonists that there are two different ways, at least, that the art and text interact. One is when the drawing is intrinsically funny and the humor of the cartoon is contingent upon on how funny the drawing is as well as the caption. Then there are cartoonists like Hokinson and maybe George Price and Charles Saxon, whose drawing is not funny. The humor is based entirely on the caption. I would put you the in the former category where your drawings are intrinsically funny.

Thank you. Maybe some people have more of a choice over how they draw. They can point to influences and say, “I grew up and started imitating this person and then I was imitating that person and then eventually my style sort of happened.” But I don’t feel like I had that experience. If I had the choice, I would not draw the way I do. I would not have chosen it. It’s just what it is.

You anticipated one of my questions. I was going to ask you a question in relation to an anecdote you’ve told about Charles Saxon. You’ve told this anecdote where he walked up to you at your very first New Yorker party and he asked you, accusatorially, why you draw the way you do. This is a deeply philosophical question. Not the way he asked it, but if you choose it to be, it could be a deeply philosophical question. Why does an artist draw the way he or she does? I was going to ask you, if the style in which you draw is a choice.

You anticipated one of my questions. I was going to ask you a question in relation to an anecdote you’ve told about Charles Saxon. You’ve told this anecdote where he walked up to you at your very first New Yorker party and he asked you, accusatorially, why you draw the way you do. This is a deeply philosophical question. Not the way he asked it, but if you choose it to be, it could be a deeply philosophical question. Why does an artist draw the way he or she does? I was going to ask you, if the style in which you draw is a choice.

I think there is some choice in it. It’s like, why are you the kind of person you are? This probably only scratches the surface, but I think that why a person draws the way they do and why they are the way they are is the same thing. Some of it is intrinsic. It’s like what I was saying before about my father and I both having this weird brain quirk with handwriting. I didn’t choose that. I have no interest in remembering these people’s handwriting, I just do. We’re not total blank slates. I don’t think we are. I think there are certain temperaments, certain things about oneself that you are born with. Then there are other things: What you’re exposed to when you’re young and how your taste is formed. Also, with handwriting and drawing for me, there are a lot of overlaps. I think about the way your handwriting is formed, how it comes out, but then some of it is, “Oh, I like the way she makes her R. I think I’ll copy that.” I can remember being in first grade and I used to draw my feet pointing out to the side like Charlie Chaplin, you know? The way little kids draw feet like that. You have no idea how to draw them pointing forward, so you draw them each pointing to the side. There was a little girl in my class who drew them pointing forward. She knew how to do that. She had an older sister who may have taught her. I copied her. It wasn’t like I copied her entire style, it was like I copied how she drew shoes. Then it eventually became my way of drawing shoes. I think that happens over time. There are little bits and pieces that you see, like a wallpaper pattern or something. Or just some little thing. Like a barnacle, it just sticks to you. You put it into your little style pile or whatever.

I don’t know if I’m being articulate or not.

I think so. I would assume it depends on how you assimilate all these influences. Whether you do it overtly or covertly.

Both.

I’m not sure I can point to any stylistic antecedents in your work. I can’t look and say, “Well, there’s —

I’m not good at following — I’m not good at figuring that out. I don’t know.

Whereas some artists, you can see when they are young that they love certain artists and they wanted to draw like them. They either continued drawing like them or they broke away finally and found their own voice. You can see all of these stylistic trails throughout the trajectory of their work. I’m not sure you can see that trail in your work. I can see where you refined your work technically over the years, but the foundation of your style was always there.

There’s definitely a thread, you know? I think, deep down, I’m kind of stubborn in a certain way.

Oh yeah. [Laughter.]

I don’t think I’m good at copying other people.

Did you ever want to draw differently?

All the fucking time! [Laughter.] If somebody said, “You can’t draw. You’re terrible, you’re awful.” It’s like, “Tell me something I don’t know!”

[Laughs.]

I think that was one good thing about RISD. When I came out, I just thought, well, OK, I know maybe I’m terrible but I want to do this anyway. I need to. And I’m going to. Somebody telling me that I’m awful or I’m not talented, it’s like tell me something I haven’t heard before. I think also there are certain artists — not just in cartoons — there are plenty of artists that have great draughtsmanship, but their work is just boring. It’s just terrible. I think the older I get, the more I don’t look at people’s artwork to admire their draughtsmanship. I don’t read a book to admire how good a writer somebody is. There are certain artists… All I can think of is Prince Valiant, you know? Great draughtsmanship, but that was one of the strips that makes me almost nauseous to look at. [Groth laughs.]

A lot of people probably said the same thing about Lynda Barry’s drawings. You compare them to someone who’s a fantastic draughtsman, but I love her drawings. I’d much rather look at interesting drawings and drawings that pull me in or a story that pulls me in. To me, that’s magic. Something that makes me laugh instead of someone who’s “so technically skilled.” “Ooooh, their technique.” I have no interest in Cirque du Soleil, you know? [Groth laughs.] I don’t care. It might be the most fantastic thing for somebody to watch somebody do an upside down somersault 40 times and catch spinning plates or something like that. A feat you know they worked on for 24 hours a day for 10 years to perfect. I’m just not interested in it.

You have no interest in technique for its own sake.

Right. I have no interest in technique for its own sake. If anything, if it’s just technique, it makes me feel even worse. It’s almost more depressing. I think, “Oh my god, this must have taken hundreds and hundreds of hours.” It’s so boring.

I guess Alex Raymond would fit into that mold for you.

I don’t know who that is.

Flash Gordon.

Oh, yeah.

Very pretty, technically accomplished work.

I have no interest in superhero stuff. And that’s a failing. I’m not interested in it.

You really consider that a failing?

I do, I do. I feel like I should be open to it, but I read three panels and then I just want to go to sleep.

[Laughs.] You shut down.

I shut down, yeah.

So, regarding Foster, do you feel there’s a sterility to the drawing?

Not a sterility, it’s just boring. I don’t understand it. I feel shut out from it. For me, when I see something that I love, it’s just so wonderful.

Do you think draughtsmanship is important in the sense that artists should learn how to draw first before they become stylistically more interesting? There should be an underlying ability to draw well? Is that important to you?

Yes, but. And the but is, who decides that? Who is the arbiter of drawing well, you know?

I did take figure drawing classes and I don’t draw anatomy, but I feel like I can draw a figure and make it sort of stand or sit on a chair or walk around. I feel like the drawing and writing have to go together. They have to pull you in in some way. But I think it’s so individual. That’s part of what’s great about this. Everybody should get to decide for themselves, you know?

Do you think the fundamental concept of draughtsmanship is intrinsically fallacious?

I think there’s not one standard to measure draughtmanship against. Somebody might say, “Before you draw cartoons, you should know human anatomy.” I disagree. I do think, for me, a general knowledge of figure drawing is important. I would feel limited if I couldn’t draw people at all. [Groth laughs.] That would be really weird. I’d probably not even want to draw. I wouldn’t want to be a cartoonist. I don’t think knowing perfect anatomy is necessary, but it’s helpful if you’re going to be a cartoonist to know a little bit about how to draw people. Everybody has to decide for themselves how far they want to go into that and how important it is to them. I know a cartoonist — do you know Julia Wertz?

Yeah.

She does these wonderful cartoons with really expressive faces and stick figure bodies. Stick figures are very expressive. They’re great. I love her stuff. To me, I love that a million times more than Flash Gordon, with all the muscles and everything.

There are some cartoonists that I don’t know if they can draw well, but I like them because the work is so expressive.

Yeah, expressive. Some people might disagree, but I feel like my work’s gotten better. I’ve gotten a little bit better at drawing perspective. Maybe I’m the only one who notices it. But it’s definitely something I still struggle with.

You still struggle with certain facets of drawing?

All the time. All. The. Time. Yeah. I patch. I redraw, I tear up, I erase, I use Wite-out. Then I look at it and realize, “Shit. That’s too big.” Then I put it in Photoshop and make it smaller. This part smaller, this part — yes, absolutely. Absolutely.

It’s OK. It’s all right. I don’t think that it’s necessary to draw everything perfectly and to have a full understanding of perspective and of anatomy. Unless you want to. If that’s what you love and it’s what you’re most fascinated by, then that’s what you should do.