Hillary Brown

Here are 10-ish comics things that got me through this awful, discombobulating year, in which I probably read fewer comics than any other year because I was busy spending my time texting people about elections or rage-crying in the parking lot of the grocery store or trying to get my kids through virtual school. My brain couldn’t focus on long things. Someone described it to me as “goldfish brain,” and that’s what it felt like. Remembering something for 2 seconds and then promptly forgetting it again. My analytical faculties were swamped. I think these things are still good, though, and they’re listed (sort of) in the order in which I read them.

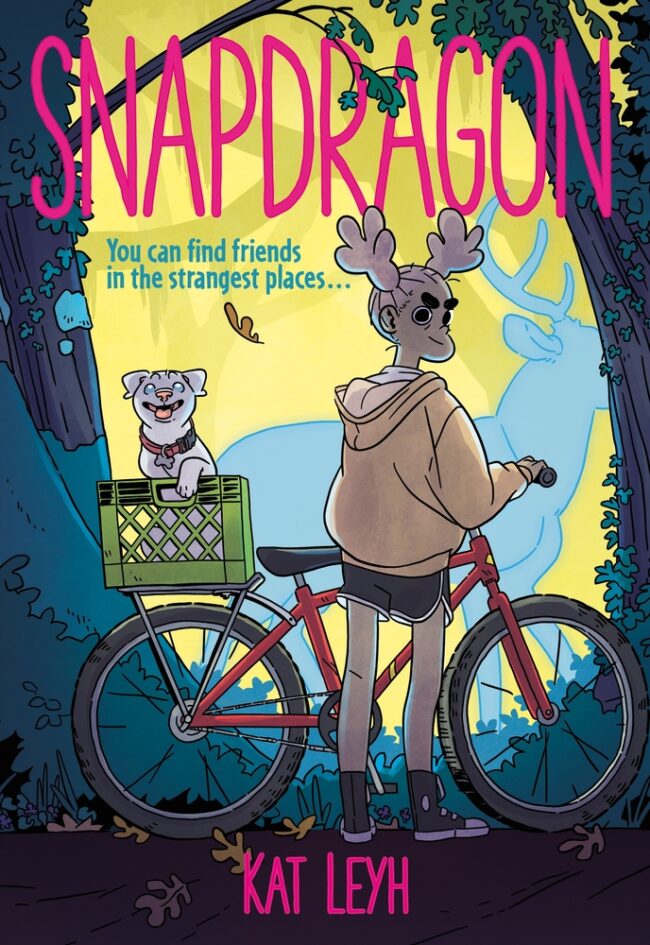

Snapdragon by Kat Leyh: Quite possibly the best book of the year. When I think about it, I feel like I have a pair of Hot Hands embedded in the middle of my chest -- that is to say, there is a weird, slightly uncomfortable warm glow inside me because this book has so much heart. It’s not gentle, but it is amazingly kind. Both Leyh’s writing and her astonishing art combine to make this transcend YA lit into a book everyone, everyone, everyone should read. I read it before the pandemic and after it had begun, and it was just as strong both times.

Becoming Horses by Disa Wallander: This book made me feel like I was inside a painting, and not like those dumb immersive Van Gogh experiences. It’s arty and disjointed and weird and doesn’t really have much of a narrative, but it sparkles. It shows what it’s like to be in someone else’s artistic sensibility. It made me feel like Alice in Wonderland.

Familiar Face by Michael DeForge: Crafted in hundreds of roughly Instagram-sized windows, generally four per page, Michael DeForge’s book is the kind of documentation of our timeline that will prove both invaluable and incomprehensible to folks in the future. Why did we torture ourselves by falling into the hole of the tiny computer we held in our hands for hours and hours a day? What did it feel like? Were we a deeply masochistic society or just one that was continually disappointed and slow to learn? He does this without preaching and without guilt. He makes us feel seen. Is it a familiar face you see when you turn on your phone’s camera and it’s in selfie mode? Or is it unfamiliar? It’s both. Are we in the matrix? Maybe? Maybe you should go outside instead.

Umma’s Table by Yeon-sik Hong: I loved this book not because it was about food (although I certainly do love food) but because it’s about everything that surrounds food preparation as an act of love. It’s a thing that has to be done most days, and it gets all wrapped up with who we are at different moments in time. This book is just as much about how your relationship with your parents changes as you get older. You want distance, but you also don’t. You begin to understand that they’re people. You start to process the inevitable goodbyes that are yet to come. It’s a very deeply felt and sensitively communicated book.

I Know You Rider by Leslie Stein: As I write this list, I’m beginning to see that every single one of these books could be described as “deeply felt.” Maybe that means nothing about the comics themselves and more about the kind of year it’s been, in which most of us had several layers of metaphorical hide sloughed off, bringing our newly sensitive, not-yet-completely-formed underskin to the surface and enabling us to feel anew again. I Know You Rider had me on the verge of tears almost the whole time I flew through it. Leslie Stein’s work is always a bit like that: about community and loneliness, fucking up and getting lucky. This one is even more so, and it makes a strong case for abortion as necessary healthcare.

The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist by Adrian Tomine: This made me laugh harder than almost anything this year as I read it in a greedy rush, looking for more endorphins. Sometimes clever is overrated or shallow, but this didn’t feel that way. It felt like a gift, a well-executed pratfall for our amusement, beautifully drawn and cognizant of our limitations as humans.

The Contradictions by Sophie Yanow: A bildungsroman about being sweet and young and romantic, Sophie Yanow’s book is understated in a way that makes it feel more intense. It makes for an interesting generational contrast with Ulli Lust’s Today Is the Last Day of the Rest of Your Life, in that both of them feature young folks hitchhiking around Europe. Lust’s book is tense with menace. Yanow’s feels a lot less dangerous and yet, at the same time, more aware of potential danger. The simplicity of her lines and panels evokes Joost Swarte, but the story about the intoxication of new friendship that shades into a more traditional crush that itself shades into wanting to be the crushee is all Yanow’s own.

Eddie’s Week by Patrick Dean: This book, the only long-form one by Athens’ Patrick Dean, finally made its way into print late this year, after a publication and creation history that was gnarled to say the least. If you don’t know what had to be overcome to publish it, it’s just as much of a ray of sunshine as if you do: a charming yarn stuffed with MacGuffins and goony jokes, drawn with style and looseness and loads of black. Equally notable are the drawings Dean has produced this year, with a pen literally strapped to his hand as his muscle control degenerates due to ALS. If Eddie’s Week is the mild-mannered fellow who’s about to be ambushed by a werewolf, then the post-diagnosis drawings are the wolf itself, howling in pure rage at inhumanity, our fucked-up healthcare system, police brutality, the endurance of systematic racism and more. The pains it takes to produce them are palpable in the hard-won lines. Dean’s newest efforts, using eye-gaze technology, often on top of photos, are fascinating, too, as an artist learns to draw one more time.

“Giving Thanks in 2020” by Eleanor Davis: It’s not really fair to keep asking Eleanor Davis to turn herself inside out for our pleasure, behaving like some kind of Visible Woman as she plops her nerves and her uterus and the muscles in her legs for us to inspect and nod at. But I’m glad she’s still willing to do it. This short comic that appeared in the New York Times on Thanksgiving and that I read on my phone, sitting on a kitchen stool next to the oven, having just put a turkey into it for a one-household gathering, was as right on as everything she does, starting small scale with an image of her clasped hands and Big Banging outward to tragedies (and their associated good points) small and large. It doesn’t feel like a bummer as she undercuts each moment of thankfulness with caveats. It feels real. We’re all thankful for her.

The Nib, every day in my inbox: Smart, sharp, well-drawn new comics every weekday in my email? What a gift it is to get Ben Passmore’s latest sent to me. Or Niccolo Pizzaro’s, Bianca Xunise’s, Pia Guerra’s, Emily Flake’s, Matt Lubchansky’s, and so on. Bitterly funny and well varied, they’ve kept me going.

Nicholas Burman

My most pleasurable reading experience of 2020 was Ryan Holmberg's translation of Yoshiharu Tsuge’s The Man Without Talent (NYRC). With its depiction of life in a liminal space at the point where an economic system is decaying, there probably wasn't a more timely reprint all year. Holmberg's translated dialogue is full of vernacular poetry, which I imagine/hope is quite close to the experience of reading the Japanese version. It certainly fits Tsuge’s gorgeous cartooning, which is often unfussy and employed to effectively tell the story, but sometimes surprises with its soft and loving approximation of the Japanese countryside and shacks full of possessions. Its combination and portrayal of quotidian melancholy and pleasures was the perfect accompaniment to much of 2020. I haven't been able to recommend this book enough.

Onto work published for the first time this year... due to my age and location (or his, depending on how you look at it), Casanova Frankenstein's work had totally passed me by up until 2020. His Tears of the Leather-bound Saints (Fantagraphics) set that right, I'm just sad to hear that he's said it'll be his last comic. Frankenstein's art is lively and animated, portraying his vignettes of life growing up as an outsider in American suburbs and cities with an energy that is totally engrossing, even if at times it is drawn in order to unsettle. The metamorphosing world of Michael DeForge's Familiar Face (Drawn & Quarterly) seems somewhere between documentary and speculative fiction, dystopia and idealistic fantasy. At its core, it is about figures - characters - attempting to understand how to be with each other, and that is a crucial and timeless changeless. Also published by D&Q, Disa Wallander's Becoming Horses took me a while to "get into", its sparse pages and lack of traditional panels begs for an atypical reading method. Once that challenge is accepted, however, it more than rewards the reader, providing a gentle dreamscape in which friendships, loneliness and playfulness are encountered. A promising newcomer to the comics scene was the UK's Zoe Thorogood. Her debut long form comic The Impending Blindness of Billie Scott (Avery Hill) demonstrates that she has ample storytelling talent and a firm grasp of inventive page arrangements. Am very excited to see her future work.

Finally, a brief mention of two self published comics. Genie Espinosa's Raras series continued this year with the Muy Raras ("very weird") issue. This is an anthology of female Spanish cartoonists and illustrators, and is proof that the Spanish scene is bursting with some of Europe's most exciting comics artists, and is a lot more diverse in tone and style than what some might associate with the Iberian peninsula. Meanwhile, Michael Olivio's DCXXXL, the collected edition of his 2020 zines, out via Cold Cube Press, boasts Olivio's deft control over both comix-esque cartooning and graphic design inspired pages that make full use of the printing process.

Clark Burscough

In terms of comics I read, I kept things safe this year, but ended up with a hefty list of things I want to try and get ahold of in the new year, based on the writing of others here and elsewhere, if Brexit doesn't turn the UK into a DMZ/shipping fees aren't even more extortionate in 2021. The below's what I remember enjoying at the time, in no real order - just stuff that I read while holed up in my flat, wearing a groove in my sofa, and that kept me from looking at my phone and/or the news.

Instagram comics were the real MVP of quarantine for me, and I really do hope that the printed editions that come out of the daily strips people were putting out get the same traction they had on social media. I read a lot of pieces about how WebToons and similar sites are being eyed as the hot angel-investment properties this year, but maximum respect to artists who were isolating and managed to do regular drops of ten panels (or more). Simon Hanselmann's Crisis Zone, Benjamin Marra's What We Mean by Yesterday, Liz Prince's Quarantine Comics, Jon Chandler's Empty Highway, HTMLflowers' No Visitors, and Nathan Cowdry's Identity Theft/Sea-Diver were all highlights when new pages showed up in my feed. However, I think it was Alex Graham's Dog Biscuits that really nailed things for me - it had that Portrait of a Lady on Fire thing going, where it absolutely demolished me on a regular basis for the depictions of physical closeness that 2020 removed, but was also a really compelling read, with nicely fleshed out relationships between the characters, and never really knowing when a new update would be funny/harrowing/both.

I reverted to type, in terms of my prose reading, this year, imbibing naught but the soapiest of science fiction and fantasy, outside of some fairly heavy medical reading for my day job. Comics had some good entries on this front, for pulpy genre escapism, especially Simon Roy, Daniel Benson, and Artrom Trakhanov's First Knife, and Johnnie Christmas and Jack T. Cole's Tartarus, both of which introduced enjoyably weird worlds and then mixed some intrigue and derring do into them. I also really enjoyed Peow's EX.Mag, edited by Wren McDonald. The mix of stories in the Cyberpunk and Supernatural Romance editions didn't outstay their esoteric welcomes, and I'm looking forward to the new Dark Fantasy volume once it drops.

2020 really messed things up in terms of sports fandom, as I missed out on a world cup AND a summer olympics, which, let me tell you, really sucks, so that might be why I really glommed onto the new editions of Taiyō Matsumoto's Ping Pong from VIZ Media - they had good paper stock, and the extreme kinetics of the table tennis action scenes almost made up for not having spent a summer staying up into the middle of the night to watch rolling coverage of international sports tournaments. Almost.

Two books that connected in my brain for reasons I'm still unpacking were Evan Dahm's The Harrowing of Hell and Florent Ruppert, Jérôme Mulot, and Olivier Schrauwen's Portrait of a Drunk. It probably says something about my status as a lapsed Catholic, but I think they have diametrically opposed views of life and the afterlife, one being a story of salvation in the face of overwhelming darkness, and the other an ode to nihilistic self-destruction, because you can't take it with you, and karma doesn't exist. Both were books I immediately re-read after finishing, and I'm glad I've got them on my bookshelves.

RJ Casey

The best comics I read in 2020 (in alphabetical order by artist, excluding Fantagraphics titles because I work here):

Precious Rubbish Vol. 1 #1–5 by Kayle E. (self-published)

"Crisis Zone" by Simon Hanselmann (published on Instagram)

Whisnant #1 by Max Huffman (self-published)

Love Man: Forever and Ever Again by Ben Marcus and David Krueger (Perfectly Acceptable Press)

The Puerto Rican War by John Vasquez Mejias (self-published)

Joe Versus Elan School by Joe Nobody (webcomic)

Sports Is Hell by Ben Passmore (Koyama)

"A Story of Mothering-in-Place During the Coronavirus" by Lauren Weinstein, from The New Yorker

"I Needed the Discounts" by Connor Willumsen, from The New York Times

Helen Chazan

Every year at best-of list time I find myself wishing I had read more of the year’s comics, and in 2020 that feeling was especially strong. I suspect that this is pretty damn near universal. The pandemic has limited access to a whole lot of new comics for a whole lot of people in a whole lot of ways, and our emotional energy to be avid, curious readers is constrained by the crisis. At risk of offering what I’m sure will amount to yet another essentializing universal claim among many, we’re all going through something right now, and it’s important that we at least have some forgiveness for ourselves as we fail to find the time and the willpower to be as productive as we think we ought to be, even if it’s our hobbies, even if it’s our leisure, even if it’s just our ability to glance at the funnies. For myself personally, quarantine aside, I also had... well... a pretty fundamental lifestyle change over the last 12 months, and I’ve had fewer opportunities than my already beleaguered grad student existence permitted in the past to find and browse for new comics adventurously or seriously engage with many of the major books that I am sure will be important to me. What can I say, womanhood ate my zine budget :P Fortunately, the comics that I am able to list include some truly wonderful examples of the medium. So I’ll quit whining and tell you what I can about my 2020 in new comics:

Emotional Support Animal Part 1 by Ivy Atoms -- technically came out last year but I wasn’t able to get a copy until this year and WOW did this hit me like a brick. Just page after page of massively inventive cartooning, thoughtful satire, vivid, loveable characters. Kind of a thematic continuation of Ines Estrada’s Alienation and every bit as idiosyncratic and visionary as that comic was. Ivy Atoms is one of the best cartoonists we’ve got.

Glaeolia Vol. 1 -- a small press manga anthology that warmed my heart. Thank you so much.

Portrait of a Drunk by Olivier Schrauwen and Rupert & Mulot -- just an immensely entertaining book, brings out the best in all the contributors involved, I was swept away by this vast and vulgar yarn.

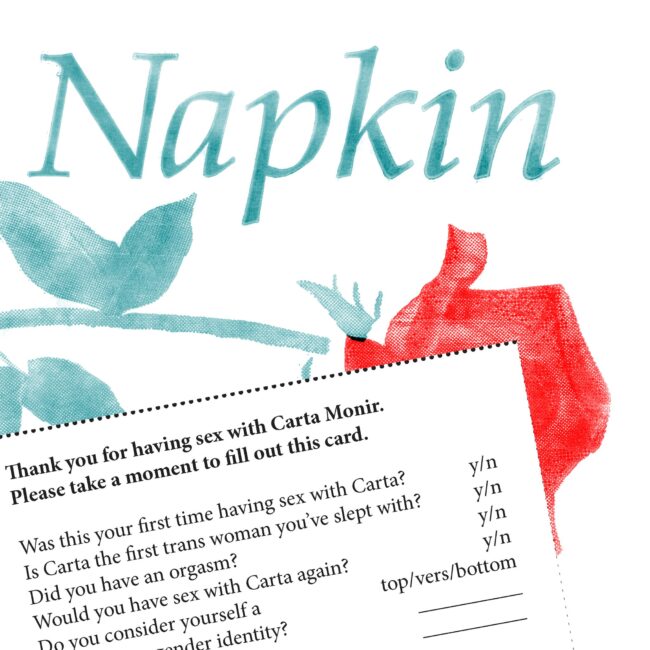

Napkin by Carta Monir (was this 2020 or 2019? hALP) -- I dunno if this even counts as a comic but in all honesty if autobio cartoonists aren’t aspiring to be saying something as significant as the profound and vulnerable reflections that Carta articulates in this zine, and if we as critics and readers don’t celebrate work like this… should this scene exist?

And Now, Sir — Is This Your Missing Gonad? by Jim Woodring -- no Frank book is a minor event, I really enjoy flipping thru this when I’m just chilling out.

Single Camera Sitcom by Lane Yates -- a largely successful serial experiment which can be found on Lane’s twitter and also elsewhere. Great for fans of the bible or that one bit in Blubber where they go to the casino.

The new issues of COPRA were good cuz I mean like of course they were. Shout out to Urusei Yatsura volume 7 for being my profile picture on twitter for a solid month there, you might not know this about me but I am literally Lum Invader.

Finally, a quick rundown of my favorite comics that I’ve reviewed for TCJ. I’ll keep my thoughts brief as you can read more about what I think in my essays and reviews:

The Sky is Blue with a Single Cloud by Kuniko Tsurita -- Greatest of All Time

Ping Pong by Taiyo Matsumoto -- Greatest of All Time

Mermaid Saga by Rumiko Takahashi -- QUEEN

920London by Remy Boydell -- personally found this very relatable, possibly greatest of all time.

Streets of Paris, Streets of Murder: The Complete Graphic Noir of Manchette & Tardi Vol. 1 -- superb, Jacques Tardi drawing dudes getting shot is one of my favorite genres.

Austin English

The Dairy Restaurant by Ben Katchor

I love Katchor's work because it's never about melodrama in the traditional sense, the mode that most storytellers employ without ever questioning themselves. His characters don't yell at each other or 'resolve' things by the end. And yet, Katchor is in no way emotionally austere. All his stories are about daily life, how people get along with their fellows. They are especially moving as they discard what we think of as required in stories about people. Some might see his work as stilted, but I think it shows how most everything else in narrative fiction is wildly unnatural.

When Crumb tackled Genesis, he took it as a straight illustration job. Crumb gets attacked plenty these days, but rarely for his narrow (or extremely on the nose) philosophical ambitions. This new book by Katchor treads the same biblical territory (and far beyond) but instead of mere illustration, we have Adam and Eve as the first demanding customers in a restaurant, and all of history from that moment onward viewed from the restaurant perspective. Like any real artist, it's hard to pin Katchor down: is this satire or a deeply serious perspective? It's both and neither, it's a comic.

Abhay Khosla

I mostly have focused on 1980's comics for a while now, so I have a poor understanding of what comics have been like between, oh, 2017-2020, around there. (I have a tremendous number of opinions about Frank Thorne's Ribit!, though, helpfully). I have a long to-read list.

With that out of the way: my three favorite comic experiences of the year were Gipi's One Story, and then finally pulling Bastien Vives's Polina and Linnea Sterte's Stages of Rot out of my to-read pile (with Stages of Rot probably my favorite experience of the bunch, of the year, the whole shebang). The latter two came out in previous years; I wish I'd gotten to them sooner. I'll probably be similarly enjoying 2020's best books about three years from now, too.

Polina just felt classy-- it sort of offers a sort of similar pleasure to that TV show the Queen's Gambit, the pleasure of watching a character find their place in the world (but without that TV show's "being on pills is awesome and has no negative consequences, all upside, go get some" subplot; so I like the Queen's Gambit a lot more, that subplot ruled, good message for the kids thinking of playing board games out there); the other two books were the closest to feeling that "blind guy trying to describe an elephant" feeling, of "an experience that can only be had through comics", where describing them too much feels like you're only emphasizing why they were made as comics to begin with.

Besides those three, choppier waters. There's my "comfort food" books for the last little: Copra, Immortal Hulk, the Long Con and Sink. Those have been my go-to for just a certain baseline level of entertainment, pleasure I can just receive in my most-preferred uncritical "brain forever empty" way. But Long Con (a goofy nerds-are-hilarious comedy that I would ordinarily run away from, but which I just like, which I just think works, one where I just like the "high concept", I guess) concluded in 2019-- I only got to the ending this year; the creative team for Sink (a splattergore anthology of single issue exploitation shockers) seems to be working separately currently on other (classier) projects (though successfully so, by the look of it; like I said, I have a long to-read pile). But so I'm down to two-- it's Copra and a Hulk comic, and then the abyss. And I find it very difficult to find other books that work in that way for me-- I mostly had misses, when I did try to find those this year. But to be fair, I was busy reading the new Aztec Ace re-release, so I didn't look too, too hard. In sum, 1980's comics over everything.

Honorary Mention: The screencaps of the Marvel Comics documentary about the making of some Dan Slott comic book that went around online. Those screencaps count as a comic! Read some theory!

Rob Kirby

Ten books in no particular order:

Kent State: Four Dead in Ohio by Derf Backderf (Abrams)

This wrenching chronicle of the infamous tragedy of 1970 humanizes the victims and breaks down the events with clarity and anger. It unfortunately remains as timely as ever.

Paul at Home by Paul Ragabliati (D+Q)

Immersive, melancholy semi-autobio, featuring masterclass cartooning.

The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist by Adrian Tomine (D+Q)

This hilarious, deliberately mortifying memoir demonstrates that success comes in various degrees of perception.

Little Lulu: The Fuzzythingus Poopi by John Stanley (D+Q)

These all-ages comics are iconic for a reason. Completely delightful escapist reading.

Wendy, Master of Art by Walter Scott (D+Q)

Sharp, hilarious, humane satire of the art school milieu.

Life on Earth 3: Distant Stars by MariNaomi (Graphic Universe)

A perfectly satisfying conclusion to this stylistically adventurous but accessible YA trilogy.

The Contradictions by Sophie Yanow (D+Q)

One of the smartest and most relatable twentysomething coming-of-age stories I've read in some time.

Motel Universe 2: Faschion Empire by Joachim Dreschler (Secret Acres)

Drescher’s naïve style, surreal characters, and acid-trip landscapes remain as delightfully bizarre as ever in this second intergalactic satirical adventure.

The Sky is Blue with a Single Cloud by Kiniko Tsurita (D+Q)

This career-spanning retrospective of a Manga pioneer is both a fitting memorial and effective showcase for her alternately hopeful and fatalistic visions of mortality.

The Burning Hotels by Thomas Lampion (Birdcage Bottom)

Quirky but sincere, this is a promising debut from an idiosyncratic creator and an excellent, underrated micro-publisher.

Online comics:

Patreon: These wonderfully personal and entertaining diary comics by Tessa Brunton, Hannah K. Garden, and MariNaomi have all been more than worth my monthly buck.

Instagram: Comics by Kelly Abeln, Lauren Barnett , and Rachael House. These women have all been killing it during Covid, with Abeln focusing on regular day-to-day with honesty and irresistibly charming drawings, House with her often lacerating, politically-slanted inky musings, and Barnett with her drolly funny existential observations (plus her recent paintings are terrific as well).

Joe McCulloch

Boston Corbett (Sonatina) - Like a gentle minicomic blown up to staggering proportions, Andy Douglas Day's not-infrequently baffling 1,384-page metaphysical revue on the life and desires of a marginal U.S. historical figure -- and other, related topics -- represents a fully alternative vision of the 'graphic novel' as a vessel for extended improvisations, chasing after the ghost of what it is to live. It's also 2020's best comic about capitalism, but that's just one interpretation of a book that gladly defies categorization.

Glaeolia 1&2 (Glacier Bay) - A sizable double-pane window onto Japan's contemporary small-press scene; invaluably educational, and very fun.

Maids (Fantagraphics) - I absolutely should not be listing a book that has me listed on the 'special thanks' page, but fuck it - this is a major evolution of Katie Skelly's narrative style, the concision of which is put in the service of a lulling depiction of daily work, broken up occasionally by memories, visions, and bursts of flush unhappiness. And then, like a stick snapped in half, the entire system collapses into bloody catastrophe, before painfully mending itself over the break. Not literally about the pandemic, but sometimes the era finds a book, you know?

Ping Pong (VIZ) - The belated English-language arrival of what's maybe Taiyō Matsumoto's most enduring work in Japan: a sports manga that superimposes its generic devices over the awkward flux of actual youth. There is probably no other popular cartoonist on Earth more concerned with the inevitability, the necessity of dreamy adolescence's assimilation into dull adulthood than Matsumoto, and his determinedly low-stakes table tennis tournaments find hot-blooded teenagers clinging fiercely to competitive ideologies that they question, swap and discard with the plausible caprice of kids their age - and in the end, all is blown away by the fact that you have to go out and get a job and assume those adult responsibilities that relegate school sports glory to a fading burn of ecstasy upon the memory. Also, this guy can draw. I mean he can really fucking draw.

Portrait of a Drunk (Fantagraphics) - A genuinely evil adventure comic.

The Marchenoir Library (Secret Acres) - A collection of cover illustrations, character info files, and advertising copy for a series of lost comics - such castoffs of marketing are sometimes the most visible remnants of works that consequence has doomed. But A. Degen knows that the diminutions of commerce can become fuel for the imagination, like assembling the bones of an esoteric body. That every major popular comics tradition in the world seems to be happening at once in these images suggests a lamentation for the blazing heart of a medium so often addressed only in those terms that reduce it to cash.

The Sky is Blue with a Single Cloud (Drawn & Quarterly) - It will be difficult for some to separate the comics of Kuniko Tsurita from the total impact of this collection, which is very much A Statement on the Life of Kuniko Tsurita, but the restless curiosity manifest in this massive sampler of unsparing art manga, once lost and newly found, is a superb and awesome force on its own.

Vision (Fantagraphics) - With little waiting beyond the thankless horizon of domestic care, a woman gazes into a magic mirror: for companionship, carnal satisfaction, and promises. But the eye is a delicate thing, and oblivion a voluptuous black cloud. Nobody makes 'em like Julia Gfrörer.

Brian Nicholson

1. Familiar Face, Michael DeForge (Drawn And Quarterly)

The last book I bought before quarantine orders took effect felt wildly prescient, describing a science fiction world that reshapes itself overnight and takes the people we were once closest to away from us. On a sheer level of writing, this was so impressive and modern, and so deeply felt, I doubt there was a work of prose fiction this year that tops it. Meanwhile, DeForge’s images unpack the text’s plainspoken voice into shapes that feel as bewildering as each new day.

2. Portrait Of A Drunk, Olivier Schrauwen, Florent Ruppert, Jerome Mulot (Fantagraphics)

So beautifully drawn and precisely engineered, with legitimately great action sequences of pirates swordfighting and firing cannons. But more importantly: in this house, we love a mean comedy, and I’ve barely left the house in months.

3. The Sky Is Blue With A Single Cloud, Kuniko Tsurita (Drawn And Quarterly)

Feels very rare for an artist with this much style to make work that continually feels like an intellectual provocation. This is truly uncompromising work that’s still continually inviting, positing a set of intellectual values it feels like no one has followed up since. I’m excited for a new audience to contend with what Tsurita was throwing down.

4. Boston Corbett, Andy Douglas Day (Sonatina)

In a year short on major books from well-regarded masters, there is more space to appreciate insane accomplishments that emerge from nowhere, weirdo esoteric communications like this, a comedy that feels vaguely sinister while building to punchlines like a kid’s parents being balloons. At some point the jokes go away and you’re just left with hundreds of pages that feel mysterious and beguiling. The real killer of John Wilkes Booth is the friends we made along the way.

5. Dog Biscuits, Alex Graham (Instagram)

Comic strips on Instagram seemed like the format of the year to me, and this was easily the best. Choosing a specific date for its events to take place on, and then examining the modern moment through that date, rather than constantly clicking refresh on the news feed to find some newly topical punchline, this sitcom/soap opera/editorial cartoon with explicit dog/rabbit people sex got its readers engrossed in its emotional drama like nothing I’ve ever seen, and while the comments section was a minefield of psychological projection caused by a generation not having the reading comprehension skills to understand fiction, it made me understand Alex Graham as a modern popular entertainer of a type and craft level I thought had gone out with the twentieth century.

6. William Softkey and the Purple Spider, CF (Anthology Editions)

The strength of CF’s work is a certain breeziness that avoids the overwrought to feel built on gesture, not just in the looseness of its drawing, but how the narrative feels like it’s built on scattering seeds, rather than constructing a labyrinth. Often, this approach leads to work a bit too withholding and inscrutable, but this comic offers its pleasures of lively, inspiring drawings easily, and it’s satisfying on a very basic intuitive level in a way few comics can match.

7. Whisnant, Max Huffman (self-published)

Improvised on a page-by-page basis, the push and pull between utter nonsense and callbacks in this created a series of jokes I feel like I’ve memorized. “My mom was a Rayman and my dad fucked a Rayman!” “Whisnant went and snapped the neck of my Nissan Cube!!!” “You knew this was a Whisnant neighborhood when we moved here.” None of these zingers count as spoilers without the necessary context of Huffman’s spring-loaded, brightly colored cartooning. The perfect dude to reboot Hi And Lois in the style of current Heathcliff comics.

8. “My Babyland,” Margot Ferrick (Los Angeles Times newspaper, edited by Sammy Harkham)

With all due respect to the thousands of pages of Drifting Classroom reprints I thoroughly enjoyed, the year’s best horror comic got told in 5 pages. Ferrick’s style is cute and warm enough you might not even register this as a nightmare, but the feeling she captures is so palpable you know it sure as shit isn’t a joke.

Austin Price

I’m going to have to make peace with the fact that I’m simply not cut out to both keep up with developments in this field AND delve further into its history. It’s a sad admission for a critic to make, but there it is: though I managed to get through over a hundred individual volumes this year, I’d guess not more than 20 of those were 2020 releases and even some of THOSE were reissues or new translations of older work (like, say, NYRC’s translation of Tsuge’s The Man Without Talent and Dark Horse’s re-relase of Makoto Kobayashi’s What’s Michael?); one of these is actually an essay collection (though to be fair I threw a collection of criticism into last year’s countdown...); many titles I wanted desperately to get to -- The Sky is Blue with a Single Cloud, The Rose of Versailles and The Drifting Classroom have been taunting me for ages -- I just haven’t found time for them: COVID may have slowed our social lives and economy to a crawl but for those of us lucky enough to still be gainfully employed there’s always more work to do; for those of us with families there’s always some new development that needs attention (like, say, a hurricane wiping out your hometown). There’s no theme here connecting these works, really, no thread that’s going to help explain away the year or what I thought of it, just a collection of stories I responded to very strongly in the moment, works that --for a dozen different reasons -- made me think that maybe there was some point in keeping up with whatever comics I could during this time.

- Glacier Bay Press’ Glaeolia Vol. 1 (Glacier Bay Books): Whatever else this year was it proved a great time for fans of less conventional Japanese comics, getting us everything from the first official English collections of Yoshiharu Tsuge’s work to Kuniko Tsurita’s The Sky is Blue with a Single Cloud, though for my money nothing was a delightful as this collection of contemporary Japanese indies courtesy of independent publisher Glacier Bay Books. It’s not that every piece on display here is going to wow you -- though I’m going to question your taste if you aren’t enamored with “Meeting at Mandarake”, “The Death of Tokutomi Juko” and “Watching the House”-- but it’s a fascinating survey of an art scene that’s almost entirely overshadowed by the larger profile releases and a strong statement of purpose from a wildly promising independent press. And a welcome palette cleanser from so much of dominant discussion about “professional,” mass market manga.

- Taiyo Matsumoto’s Ping Pong (Viz Media): Which is not to say there isn’t good mass market manga, nor that it’s somehow not worth talking about. Ping Pong isn’t just a joy to look at -- an example of panels-in-motion, of comics from a school of kinetic, fluid shape and form -- but one of the most moving investigations into the connection between talent and fulfillment and competition I’ve ever read. I can imagine that whether you’re struggling with imposter syndrome, a fear of fading talent, or just burn-out and fatigue there will be something Matsumoto’s story of young men trying to understand who they are through the lense of competition to get you through it. Or, at least, to not make you feel so damn alone with it, and that’s not nothing in these dark days.

- Yoshiharu Tsuge’s The Man Without Talent (New York Review Comics): I doubt anybody reading Tsuge’s last major work is going to find a similar comfort; it’s bleak in the way of the classical Japanese “I” novels that The Man Without Talent owes so much to, dreary in that it leaves you stuck in the closed loop of a narrow mind that’s as aware of its dissolution and delusions as it is resigned to them, just totally given over to accepting its condition as an undeniable fact and not something that can be grappled with. In some ways it’s like a dark mirror to Ping Pong, the story of a man who has absolutely nothing going for him and little to contribute, who understands how badly cut off he is from his world and tries to cope with it by suscribing to a myth he doesn’t even half believe in. For all that melancholy, though, and for the unconventional style that might lead people to dismiss Tsuge as unsophisticated, it’s also beautiful work: the spreads showing the banks of the river and the so-called “birdmaster” leaping from the floodgates are haunting work, just indelible.

- Kohta Hirano’s Hellsing, Deluxe Editions 1 and 2 (Dark Horse): Rereading these collections -- now made available in gorgeous hardbacks (and surprisingly affordable, given how much some of the rarer volumes are) -- reminded me of why it was that I gave up on American action comics entirely back in the mid-2000s. There really is nobody doing action comics like Hirano, nobody at all who can match his decadent obsession with eccentric spreads of comical violence, who gives themselves over to sheer spectacle the same way: the spread of Alucard’s repurposed aircraft carrier crashing into the London shore, of the Vatican’s armies massing, of Seras in the throes of transformation, all of it’s just so wildly expressive -- the inks so deep and bold, the poses so delightfully flamboyant -- all of it so transcendentally playful that even the pulpy narrative starts to achieve an operatic quality its absurd premise doesn’t really warrant. A landmark action comic that deserved nothing less than this release.

- Lonnie Nadler, Jenna Cha, Brad Simpson and Hassan Otsmane-Elhaou’s Black Stars Above (Vault Comics): I’m as big a fan of cosmic horror as I am a hater: when it’s good -- as with Laird Barron, a choice few John Langan stories, Gen Urobuchi’s Song of Saya or Thomas Ligotti, and, yes, despite his bigotry, Lovecraft, there really is nothing better for capturing that overlap between utter horror at the frivolity of all life and the sublimity of standing before the utterly incomprehensible. Unfortunately, so much of it’s a snooze, either deeply, laughably derivative (how many more Necronomicon-style occult texts can we stomach, how many more Great Old Ones can be added to the pantheon?) or didactic and sanctimonious, repurposing Lovecraft’s disgusting bias to remind us that this bias was always deeply revolting. Luckily, Nadler and company’s Black Stars Above falls much closer to Alan Moore’s Providence than it does to Matt Ruff’s Lovecraft Country, using the frame of cosmic horror to tell us a story that draws as easily from Lovecraft’s conceits as it does from the cinematgraphy of Kubrick and the art of Jacen Burrows as it does from the intentionally antiquarian prose of writers like Cormac McCarthy to examine not just the horror of surviving in a world directly hostile to you but as well the horrors unleashed by Canada’s colonial settlers and the twisted moral justifications they made for the same. The ending was a little too optimistic for my taste, but there are moments here that ring with real cosmic dread, images and scenarios that take me back to discovering Lovecraft in the back of a moldering old library half a lifetime ago.

- Evan Dahm’s The Harrowing of Hell (Iron Circus): I wrote about this less extensively than I would have liked as part of a retrospective on Dahm’s comics for the Journal, but suffice it to say that I found it a beautiful and timely addition to his body of work that’s also an interesting departure in some ways from his earlier works (though, as argued, very much in line with them in other ways). It’s a haunting piece about the dangers and responsibilities inherent in storytelling, about the ability of the powers-that-be to coopt almost even the most revolutionary of texts, and the hell we’ve all ended up in by endless worship of authority and, consequently, “objectivity” that works to repurpose so much of the revolutionary elements of Jesus’ preaching at a time when his most vocally “devout” adherents are more than happy to contravene everything he espoused.

- Inio Asano’s Dead Dead Demon’s DeDeDeDe Destruction, Vol. 8 (Viz Media): Not to shit on Downfall, which Viz released earlier this year, but Destruction has been my favorite work of Asano’s since Goodnight Punpun and volume 8 just seems poised to make good on the best of it. Nobody else caputres what it’s like to live in a time period that feels this frozen, this hopeless, this meaningless the way Asano does and no work of his gets to the heart of that quite so well as Destruction does. Is it a handbook for surviving the end of the world? No; as Asano himself says, the world’s already ending; there’s no surviving it. At least you might find solace in those who acknowledge that.

- Ryan Holmberg’s The Translator Without Talent (Bubble Zine Publications): Not a comic, not even really an essay collection on comics so much as a tour of Holmberg’s last two years on fellowship in Japan, but man, is it an insightful look not just into how he translates and the history of what he translates but why he’s translating: so much of the political significance and background of Japanese comics either gets whitewashed by well-meaning Western audiences applying readings so diffuse they mean practically nothing (“Oh, hey, One Piece is about freedom! Luffy’s ACAB!”) or deliberately regressive (“It’s all just entertainment, STUPID! Japan doesn’t have SJWs like America does!”) that it’s deeply refreshing to find a scholar invested examining and explaining the really radical stuff, from Katsumata Susumu’s anti-nuclear tracts to Kaihara Hiroshi’s unsparing political cartoons. It doesn’t hur tthat Holmberg’s funny and witty, or that he’s regularly getting pulled along by these artists on adventures to nightclubs and neighborhood watering holes.

- Makoto Kobayashi’s What’s Michael?: Fatcat Collection 1 (Dark Horse): I like it when cute cats do cute things.

Oliver Ristau

I'm still convinced that during the recent decade there hasn't been a year in comics as delivering as 2017. I painfully missed the diversity in style offered three years ago, but to be honest, even if 2020 DID held a candle to 2017, I would have barely noticed...because from one day to another, when looking at drawings, I no longer felt drawn in. *slow clap*

Feeling suddenly robbed of the thing I've been devoting a disproportionate part of my life to, I struggled to come up for air i.e. finding some other satisfying while simultaneously disturbing æstheticism, but I just the fuck couldn't. Hence, before finally setting my enshrined copy of Saga De Xam on fire and dancing around its glowing ashes, in a desperate attempt I turned to the wacky world of fashion where the view through the lens means everything...at least since it's possible to capture things on film.

So I ended up with the April issue of Vogue Italia, edited by Emanuele Farneti and remaining one of the most innovative periodicals within the worldwide fashion franchise ruled by publishing empire Condé Nast. Italy, being hit much harder than anyone else in Europe by the virus known as Covid-19 during its approximate beginnings in Spring 2020, saw the April issue of Vogue Italia released with a blank cover to commemorate the many victims and to acknowledge the collectively made efforts against the virus – which is an oath of disclosure if your unique selling point commonly is showing unusual fabrics turned into hyper-trendy garments.

However, it was the kind of statement featuring exactly that lasting impact I was wishing for in comics back then, so Italian Vogue's April issue is my first best comic of the year, because you can read its fashion editorials like sequential art, too – besides equaling Danish dynamite Allan Haverholm, who's “skirting the periphery of comics”, which more or less stands for reading collections of carpet patterns as sequential art. And photo comics being sometimes paraphrased in English as Fumetti, actually the Italian term for a drawn or better, any comic, makes this thesis even more complete.

By the way, this year's January issue of Vogue Italia featured only drawn fashion editorials and also variant covers by the likes of Milo Manara or Yoshitaka Amano, but due to a complete abstinence from anything even remotely looking like a pattern of lines that one flew underneath my radar for some time. A kinship to comics tenderly arose, though – the fashion illustration reared its beautiful head, a missing link between fashion editorials and comics.

So while being half-comatose and mostly swimming in a flux made of pizzazz-devoted magazines like Tush!, L'Uomo, Antidote or Vogue, I ordered Violent Delights by Hetamoé from the mini kuš! series, because its dissident aggressor style of coloring/narrating unexpectedly appealed to me. In the meantime, having been drilled to read the storytelling simmering below those belts shown in fashion editorials, Hetamoé's heavily experimental deconstruction of mass-compatible icons as Sailor Moon due to dragging her through a violently colorful mire – which the Latvian editors described as *subsemiotic* – and rooted in Romeo & Juliet by “some” unknown writer (an innuendo on the hordes of unrecognized ground workers in the anime and manga industry), caught my eye. A meta manga, my first crush following up the first five minutes after death, if you so will.

But my relationship to comics still remained a lukewarm thing, until Japanese dessinatrice Kuniko Tsurita appeared on the horizon. *very slow clap*

Collecting works of the first woman to ever draw for alternative manga magazine Garo, The Sky is Blue with a Single Cloud is actually NOT a new comic – which might substantiate my claim that there's not much happening in comics right now, exceptions proving the rule, of course. Anyway, I fell in love immediately. And my heart and tummy are always right, here's fellow eternal Jog to confirm my infallibility. Furthermore, please take note of this lil' thread I created, it'll surely solve any further kind of doubt.

After my miraculous resurrection, I went for Hamburg's comics festival, annually held in October, which took place in despite of Covid-19 because of running a very convincing concept to rule out any possibility of super-spreading the virus. If you're among Jog's thousands of German-capable followers, here's the report from 2020.

There I discovered two comics, which were so much better than the stuff getting awarded in Germany every other year: the first one was by Noëlle Kröger and goes by the name of Das Unbehagen des guten Menschen ("The Discomfort of the Good Person"), which can be read as what it is or as subtly conking virtue signalers on their heads. After all, it's a work belonging in the flourishing German landscape of the literary adaption, but it adds a very differing tone of a *trans* voice to the original play of Bertolt Brecht's The Good Person of Szechwan, resulting in far-reaching consequences for this story culminating in an appropriately defoliating and autumn~y style by Kröger.

The other star lighting up the bleak alleys of Hamburg's famous district St. Pauli was Grandmas [sic] New Friend by Helen Serpentin in complete wordlessness, just like an average Tumblr stealing your art without ever giving credit. But that's where these kinda similarities end, because Serpentin doesn't need to borrow other people's ideas or creations, since she's a force of nature. You don't see a debut like hers very often, and here's the trick: if you're introducing bread by tickling the Proustian memory, you don't have to use words when crossing the realms of synæsthesia, while feeding the reader's by and on the other hand with amounts of spatial disorientation through unconventional perspectives and suggesting a closeness almost too intimate.

So hasn't the German read ANYTHING mersh during this anomalous year? Yes, he has, and it's – of all things – The Quarantine Comix Special presented by the Image-published horror series Ice Cream Man! You might argue that all titles released by Image technically count as horror (my apologies to Emma Rios, who apparently is a goddess), but c'mon, to each his own, that's their business model.

There's an array of guest artists in this special and at least two of the featured stories need to be highlighted: Mene, Mene, Tekel, Upharsin ("Counted, Counted, Weighed, Dissected") by Deniz Camp, Artyom Topilin with Aditya Bidikar is just what its title suggests in glorious religious fashion, a hidden meaning in any word or a “hello Latvia, subsemiotic” occuring in several panels, mixing seemingly clumsy children's drawings with a hypothermic style in a very frightening Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder scenario.

Thefollow up is even weirder, Midsommar director Ari Aster gets slapped in the face by Playmobil toys and that's all Al Ewing and PJ Holden need to burn down piled-up plagiarism when staging tokens in a test assembly for Creature Causeway and ripping out the heart out of your fuckin wicker chest.

Finally, the best comics come out short before Christmas, are self-published, brilliant and from England. This year it's Threadbare by Gareth Brookes, and the way I went through this twelve months of mostly mayhem inevitably had to lead me in its direction. It's an embroidered comic (actually it reproduces the embroidery done by Brookes), therefore the place where the embroidery frame mutates into a panel or vice versa. While traveling on a train Brookes overheard a conversation between two women about love, sex and despair. After that Brookes depicted the dialogue's vivid energy in dangling loose ends therefore showing his protagonists getting entangled in the scrub of love. That's very sexy, because the mixed yarns produce an idiosyncratic tension on their very own. By letting some of the embroideries unfinished, he's provoking the reader's imagination thus turning the heat on.

I'm pretty sure Vogue Italia would welcome an imaginative artist like Gareth Brookes with open arms, and so this is, at least to me, the most fashionable comic in an otherwise awful year. Ciao babies!

Cynthia Rose

- Black-out, by Loo-Hui Phang with art by Hugues Micol; Futuropolis. "Black-out" follows the Hollywood Babylonesque adventures of a fictitious mixed race star through the '40s and '50s. This protagonist's features enable him to play any non-white character and Phang inserts him into classic after classic. But, post-McCarthy, his image is censored – so he is rendered invisible to history. This story, ten years in the works, arose out of its creators' wish to work on a BD about cinema. Micol's art is wonderful: expressionistic and, of course, all in black and white. The portrait of Hollywood won't surprise real cinephiles but, like the hero, it's handsome and provocative.

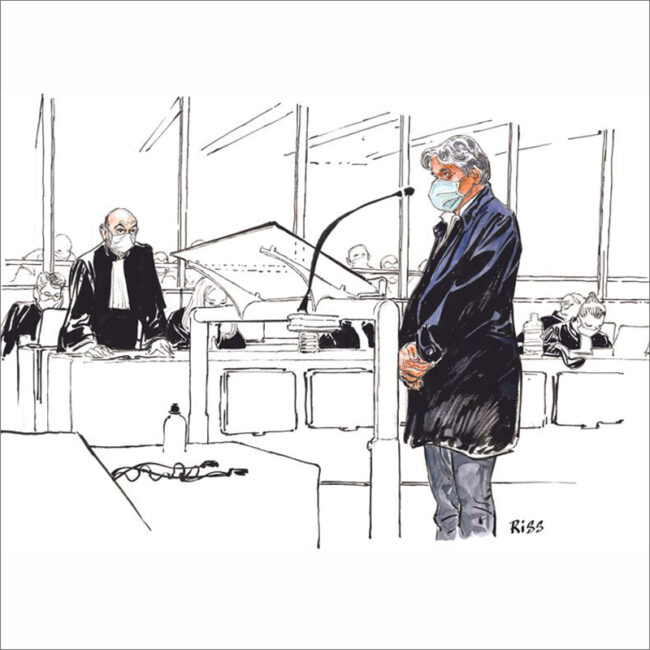

- The just-ended Charlie Hebdo/Hypercacher trial ran for fifty-four days. For all of them, François Boucq was the courtroom artist. Published every day by Charlie Hebdo, his work was some of 2020's most important. Boucq has also illustrated New York Cannibals (Le Lombard), a fourth collaboration with Brooklyn-born Jerome Charyn. Their tattooist hero's art transforms not only bodies but also souls and the city arounds him is pictured as an organic entity. Boucq tells both stories with brilliant, fluid style.

- Des Souris et Des Hommes ("Of Mice And Men"), Rébecca Dautremer; Editions Tishina. Illustrator Dautremer is well-known for children's books and for illustrating Alessandro Baricco's "Silk". But her BD version of Steinbeck's short novel is singular. Her 420 pages of often astonishing art make it one of this year's biggest hits.

- À Mains Nues ("With Bare Hands") by Leila Slimani, illustrated by Clément Oubrerie; Editions Les Arènes. This is Volume 1 in the story of Suzanne Noël (1878- 1954). The female pioneer of plastic surgery, Noël was critical to reconstructing World War I's mutilated faces. Her unexpected career is aided by her love of art, her atypical husband and tenacious lover and her male mentor in medicine. The book is written by novelist Lëila Slimani, a Goncourt Prize winner. It's drawn by Clément Oubrérie, whose Pablo revolutionised BD biography. Thus "À Mains Nues" is neither didactic nor overly PC – nor is it predictable.

- Légendes, dessiner dans les musées ("Legends: Drawings from Museums"), Emmanuel Guibert; Dupuis. The winner of last year's Grand Prize at Angoulême, Guibert is a crusader for drawing, including art for hospital patients. "Légendes" collects thirty years' worth of sketches he's made in museums. They're annotated by "conversations" with the likes of Bosch and Delacroix, as well Guibert's thoughts on drawing and storytelling.

- Charlie Hebdo, 50 ans de liberté d'expression ("50 Years of Freedom of Expression"); Les Echappés. After the beheading of teacher Samuel Paty, this collection shot to number one in the French sales charts. It's still among 2020's best-sellers. But it was published to mark Charlie's 50th birthday via cartoons, reportorial drawings and articles from the range of artists, writers and thinkers who have contributed to it since 1970.

- La Fuite du Cerveau ("Flight of the Brain"); scenario and art Pierre-Henry Gomont; Dargaud. When Albert Einstein died, he declined to will his body to science. But his brain was stolen by pathologist Thomas Stoltz Harvey. Gomont spins this true story into a fantasy with three protagonists: the thief, his comely colleague and Einstein himself (now, so to speak, topless). It's everything you want just now: witty, stylish and full of delightful touches.

- Les Belles Personnes ("The Beautiful People)", Chloe Cruchaudet; Editions Soleil. This charming book was a project for the Lyon Comics Fest. Artist Chloé Cruchaudet (Mauvaise Genre) wanted stories about people who do good anonymously. Her public call for testimonials brought her a world of phantom Samaritans, life-changing gestures – even singing trashmen. Rather than meet these heroes and heroines, she chose to imagine their individual stories.

- Ciné Aventures, Simon Roussin (Edition of 250 signed copies); Editions Arts Factory. Twenty pages of full-colour, fantasized movie stills by the bédéiste Simon Roussin, whose visual meditations on movies are something special.

- The Complete HATE by Peter Bagge; Fantagraphics. One of modernity's great gems of sociology, characterization and graphic genius – and, here, all in one place. An essential!

- La Forêt ("The Forest", by Thomas Ott; Les Editions Martin de Halleux. Swiss artist Thomas Ott specialises in evocative black-and-white "scratch-card" art. Ott prefaced Les Editions Martin de Halleux's 2018 Frans Masereel, l'empreinte du monde and Masreel was the inspiration behind this work. Its textless pages follow a boy fleeing a funeral. Only by entering a dark and ominous forest does he come to terms with his loss. The book's original art will go on show at Paris' Galerie Martel from January 15, 2021.

- Aubrey Beardsley, Rmn/Musée d'Orsay. This is the catalogue of a landmark show that, due to Covid, few people have seen. It certainly can't convey what an actual Beardsley does (there's a reason he's so influential). But, by publishing many unseen drawings – among them caricatures of Whistler, Wilde, etc. – it reminds lovers of graphic art about two things. One is why someone who died at 25 remains so important. The other is how early on artists from Japan changed their Western counterparts.

Matt Seneca

Portrait of a Drunk, by Ruppert & Mulot and Olivier Schrauwen

The rare creator team-up that earns a place next to any of its contributors' solo books, this piratical romp shoves the tropes of boy's adventure fiction well past puberty and into a piss-sodden mix of hysterics and hilarity. Its thoroughly reprehensible, near-Sadean central figure staggers through a colonialist maritime voyage full of collateral damage, leaving both murder victims and the reader in a state of purgatory, appalled by his actions while unable to look away. Sober, capable linework drowns in irregular sloshes of intoxicating color to complete a destabilized, destabilizing picture.

The Swamp and The Man Without Talent, by Yoshiharu Tsuge

It's tough to remember the last time such a major talent received the impressive introduction to the English-speaking market that Tsuge did this year. What appears to be a monumental career arc is bookended by these two volumes, with The Swamp (1965-67) building from its author's early, minor stories of ribaldry and frustration to his first masterpieces, abbreviated works of a focused intensity that half a century of comics history has done nothing to reduce the impact of. The Man Without Talent (1987) is even more special, a final despairing blast from a brilliant artist worn down by the workaday reality of plying his trade. On the strength of the work alone - the characters both major and incidental, the weary meandering of the plot, the scalpel sharpness of the dialogue - it excels any of the sad-sack "frustrated creative" works that built the institution of alternative comics in North America. But Tsuge also goes such works one better by never removing his attention from a national economy and culture that created not just one Man Without Talent but whole generations of them. How can a work so religiously devoted to rudderlessness speak with such urgency? Genius is the easiest answer.

J & K, by John Pham

Nothing else came close to looking as good as this book in 2020. The pure visual slap of Pham's kawaii, John Stanley-meets-Norakuro drawing and the gauzy blankets of neon risograph fuzz that he slathers all over it makes looking at other comics cause for outright disdain. But once one makes it past the verve and beauty of Pham's images (and the stickers this book comes with, and the trading cards, and the poster, and the vinyl record, and...), what sticks out is the lightness of touch with which he tints his titular best friends' adventures. There's a cast of mind that makes even the funniest jokes a little sad, even the best times a little blue, and Pham absolutely nails it. That this is the abiding impression made by a book featuring gag after perfectly delivered bathroom gag (up to and including sentient acne as a major supporting character) points toward the conclusion that Pham is working on as high a plane as the funny sadsters who influenced him, from Chris Ware to Charles Schulz. His stuff just, you know, looks better.

The Sky is Blue with a Single Cloud, by Kuniko Tsurita

A collection of historical manga by an artist more out of nowhere than Tsuge, this book presents something that even in comics is a rare occurrence: a truly great artist who influenced nobody. Mitsuhiro Asakawa and Ryan Holmberg's biographical tracings convincingly paint Tsurita as a woman out of her time, discounted if not outright scorned by the male-dominated gekiga scene of 1960s and '70s Japan. If Tsurita's own time and place was unfit for her brilliance, I'm not sure the here and now is ready either: from the hyperactive viciousness of Sky is Blue's early stories to the glacial burn of its concluding later pieces, this book presents an artist never willing to sit still. The best stories here collected imagine the visual elements of comics a little differently than both any other of Tsurita's works, and any other comics at all. Running through each one is a feeling of silent stillness that's peaceful and caustic in equal measure. These visionary comics feel less created than accessed, by an artist operating on her own private frequency.

William Softkey and the Purple Spider, by CF

CF's first proper "graphic novel" since Powr Mastrs a decade ago sees a familiar, unorthodox creativity and skillset pushing at a different set of tasks, with the surprisingly relevant parable of an exterminator whose super-rich employers underestimate him just a bit too much for their own good. The class struggle this book foregrounds is both surprising from CF the fantastist, and obvious from CF the exemplar of a certain kind of American underground culture. At any rate, the real draw of this book is, as ever, seeing the way its master artist unspools line and form to weave a web of narrative, one whose strands at first seem too far apart and flimsy to entangle the reader, but do just that with grace and ease.

Vision, by Julia Gfrorer

Gfrorer's clinical, scarily unsentimental treatment of a period story both dark (madness, blindness, poisoning, ghosts) and disgusting (the lancing of cataracts, the use of chamber pots, ugly people having animalistic sex) is comics as a tightrope walk. Gfrorer's bald, unflinching presentation of her bombastic subject matter could easily result in parody or farce, but her skill with gradual character development and the constrained fury of her scrawled markmaking instead render the direct approach far more unsettling than things left unseen could be. This is a work of total commitment - to setting, to a certain abstruseness of narrative, and finally to treading firmly on the reader's nerves - and the intensity of both the effort put forth and the content summoned up result in the best horror comic in years.

Tom Shapira

- Usagi Yojimbo (IDW)

It’s easy to ignore Usagi Yojimbo because it has been good, is good and will (probably) remain good. When you carry on doing your thing on the same excellent level for over three decades people start taking you for granted. Well, I am refusing to take Stan Sakai for granted – every year he still publishes more tales of the long-eared Ronin is a treasure. We are more than a year into the new, colorized, era of the series; and while I still don’t consider the change an improvement (B&W forever!), it’s simply impossible to dislike this comic-book.

- The Contradictions (Drawn & Quarterly)

Sophie Yanow’s new graphic novel takes the familiar road-trip narrative and finds new life within it. Note, in particular, her fine observation of human body language – the way she can find whole conversations just in the way characters are sitting across one another.

- Judge Dredd: The Victims of Bennett Beeny (2000AD / Rebellion)

From being a lead writer for ages upon ages John Wagner chose to mostly withdraw from the character he created (ad which made him famous); popping out about once a year to show all the young whipper snappers how to get it done. The three-part serial “The victims of Bennett Beeny” is another team-up with Judge Dredd: America artist Colin MacNeil, in collaboration with Dan Cornwell. It’s as tight and taut a thriller as any the two ever worked on: Dredd and Co. must work their way up a building held by well-armed freedom fighters / terrorists. Between all the shoot’em ups side character Judge Beeny also has a good long think on her legacy and her place within this violent system which echoes particularly well this year.

- Wicked Things (Boom! Studios)

This detective-comedy continuation of John Alison’s long-running web-comic is not as strong as his writing on Giant Days (which still puts him above 99% of the market); but even if the writing was much weaker the series would still find a place on this list for the God-tier cartooning of Max Sarin. There’s simply no one better, when it comes to humor, from the current crop of artist – able to wring smiles even from the rightest and frowniest of lips.

- Don’t go Without Me (ShortBox)

ShortBox continues to impress with both their selections and designs: This collection of three short stories from Rosemary Valero-O'Connell moves with ease between modes and emotions, each panel and page flows into the other as Valero-O’Connell creates entirely new imaginative realities as a chance to explore the depth of human attachment, memory and love.

- A Map to the Sun (First Second)

Slone Leong’s graphic novel is a tour-de-force of artistic skill: each page is (impossibly) better looking than the previous one. Eschewing the soft-edged cartooning or attempted-realism one usually finds in such stories in favor of broader and more exciting color palate that washes the world in shades of heightened neon.

- Maids (Fantagraphics)

Satan bless Katie Skelly. She has discovered the best way to open a story – an image of an eye, on the floor, and a mysterious figure approaching silently. This is a book of textures, you do not only see Maids, you hear it and smell it and feel it as well. This book is alive and kicking in your hand, pulsating like a heart just recently torn form a chest. To read it is to feel these final few pumps of the dying organ, before the gates of hell open wide.

- Copra (Image)

Like Usagi Yojimbo, Copra is always good and thus easy to take for granted. Unlike Usagi Yojimbo, which found its own relaxed paced early on and stuck to it, Copra is all about the headlong rush. Not just in terms of plotting, the series never rests on its laurels, but in its entire relation to how a comics should like: every issue feels like a personal challenge by Michel Fiffe to himself, to do something new and exciting, and every time he passes that challenge.

- The Swamp (Drawn & Quarterly)

The first in a new line of books dedicated to the works of Yoshiharu Tsuge, there’s something quite primitive in the stories presented in The Swamp. This isn’t the work of a master assured in his position, but of young person with all doubts of a first-time creator. This sense of primitivism does not hinder, and in fact helps, the atmosphere of these stories: all concerning desperate individuals, trying to make do on the edges of respectability. These are often sad stories (or at least, stories of sad people), but Tsuge manages to avoid making his work a one-note and constantly finds humanity (both good and bad) in his protagonists.

- Tunnels / Minharot (Keter Books)

English readers aren’t going to get this until 2021, but if you know Hebrew (or German) you probably already got a chance to read the new graphic novel by Rutu Modan. It’s her best one yet. It’s over-long and over-ambitious but also-over good (is that a thing? I am making this a thing). There’s a sprawling cast of characters and a plot takes us across boarders and ages and lots of twists and turns and surprises and betrayals and revelations. It’s also the funniest thing you’ll read. It’s a comic that has everything. And also a bit more than that.

Frank Young

REINCARNATION STORIES, Kim Deitch

GROSS EXAGGERATIONS, Milt Gross

LITTLE JOE, Harold Gray/Bob Leffingwell

INFERNO, Art Young

THE SUPER FUN-PAK COMIX READER, Ruben Bolling

assorted daft pre-Code horror comics of the 1950s

OLIVER'S ADVENTURES, Gus Mager